Abstract

There is a need for more knowledge of valid and standardized measures of mental health problems among children and adolescents with intellectual disability (ID). In this study, we systematically reviewed and evaluated the psychometric properties of instruments used to assess general mental health problems in this population. Following PRISMA guidelines, we reviewed empirical research published from 1980 through February 2020 with an updated search in March 2021 in Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Health and Psychological Instruments, CINAHL, ERIC, and Web of Science databases. Forty-nine empirical articles were included in this review. Overall, the review indicated consistently better documentation of the reliability and validity of instruments designed for the ID population compared to instruments developed for the general child population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cooccurring mental health disorders are more frequent in the intellectual disability (ID) population than in the general population (Einfeld et al., 2011; Munir, 2016). Mental health disorders result in reduced functioning and an increased need for help in everyday life at home, at school, or at work, in addition to difficulties due to ID (Einfeld et al., 2011; Halvorsen et al., 2019). These difficulties are associated with reduced quality of life for the person and the family (Hastings et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2009). Accordingly, careful assessment of mental health should be an essential component of care for all people with ID and should be integrated into clinical practice. The identification of mental health (MH) disorders is, however, considered difficult due to the considerable symptom overlap between ID and MH disorders and the problems of distinguishing between the conditions (Einfeld et al., 2011). Additionally, accompanying communication difficulties and atypical symptom presentations associated with more severe ID make assessment challenging (Stratis & Lecavalier, 2015). The use of relatively broadband standardized instruments is generally recommended in the initial assessment of MH disorders. There are few currently available instruments that have been specifically developed for children and adolescents with ID (e.g., Aberrant Behavior Checklist [ABC]: (Aman & Singh, 1986); Developmental Behavior Checklist [DBC]: (Einfeld & Tonge, 1992), and accordingly, instruments not originally developed for this population are commonly used (e.g., Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment [ASEBA]; Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ; Goodman, 1997]). However, there is a need for more knowledge of valid and standardized measures of MH problems among children and adolescents with ID. A previous systematic review evaluated the suitability of MH measures, in terms of psychometric properties (i.e., reliability and validity), that are commonly used for people of all age groups (i.e., children, adolescents, and adults) with severe and profound ID (Flynn et al., 2017). Flynn et al. (2017) found that very few measures were available and recommended (i.e., sound psychometric properties) for adults. Furthermore, they found no eligible studies reporting psychometric properties of instruments for children and adolescents with severe and profound ID. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for more knowledge about the reliability and validity of MH instruments used among children and adolescents across the whole ID spectrum. Such knowledge of measurement properties will provide the clinical and research field with important new knowledge regarding the strengths and weaknesses of these instruments and provide input to further developmental needs in this field.

Objective

This systematic review aimed to provide an overview of relevant general measures for assessing MH problems among children and youths with ID. More specifically, the research question was the following: What are the psychometric properties of measurement tools used to assess general MH problems in children and adolescents with ID at ages of 4–20 years? We set this age range (i) Because very few MH measurement tools have been developed for children under age four years and particularly for the ID population, and (ii) we wanted mainly children/youth samples because this was the focus of this review and including adults could provide findings that are not necessarily transferable to children.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO, an international register for systematic reviews with health-related outcomes (CRD42020172186). PRISMA guidelines were used for the reporting process (Moher et al., 2009). The PRISMA checklist is available in Appendix I.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included papers if they met the following criteria: (a) at least 70% of the sample in the study were reported as having an intellectual functioning equivalent to a full-scale intelligent quotient (FSIQ) ≤ 80 either by means of a standardized intelligence test or a diagnosis of ID or indirectly by parent report or being a pupil at a special school for children and youths with ID. (b) All studies were based on samples that included children and youths between the mean ages of 4–20 years. Samples reporting participant age above 25 years of age were excluded as the focus on this review were on children and adolescents. (c) Reported original data on quantitative or psychometric outcomes for general MH measures published in a peer-reviewed journal or as a PhD dissertation. (d) Focused on the development, adaptation, or evaluation of a measure of MH. The inclusion criteria for MH problems were derived from the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (World Health Organization, 2010). Eligible MH problems and their key diagnostic symptoms, with onset usually occurring during childhood and adolescence, were classified as follows: (a) F20-29: schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders; (b) F30-39: mood (affective) disorders; (c) F40-48; neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; and (d) F91-94 behavioral and emotional disorders. Accordingly, we did not include disorders of adult personality and behavior (F60-69), organic mental disorders, disorders due to psychoactive substance abuse, behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors, neurodevelopmental disorders (ID, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, or specific developmental disorders), motor disorders (Tourette syndrome), or other behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence that are not within F91-94 (e.g., pica or stereotyped movement disorder).

We excluded the following types of papers: (a) Published before 1980 in accordance with Flynn et al. (2017) (b) used specific MH measures with fewer than two symptom domains as the focus in this review was on broadband/general measurement tools, (c) focused on evaluating psychotropic drug interventions, or (d) reported only descriptive mean scores for ID samples (e.g., genetic syndromes) with no other psychometric information.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

We searched Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Health and Psychosocial Instruments (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), ERIC (EBSCO), and Web of Science from 1980 through February 21st, 2020. The trial registers ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) were also searched for ongoing and unpublished trials on May 16th, 2021. An updated search for each included measurement tool was performed on March 13th, 2021.

The search strategy was developed by an information librarian (BA) using a wide range of search terms for intellectual and developmental disabilities, MH issues, children and adolescents, and psychometric properties. No limits were applied to the study design, language, or publication type. The search strategy was adapted to each database (see complete search strategies in Appendix II).

The bibliographies of all included studies and previous systematic reviews were also searched for relevant studies. We contacted experts in the field to identify additional unknown studies; four additional papers were identified in this manner, but none met the inclusion criteria (Brinkley et al., 2007; Kaat et al., 2014; Ono et al., 1996; Siegfrid, 2000).

Study Selection

All titles and abstracts were independently screened by at least two reviewers (MBH, (screened all references), BA, SBH and MM) in Covidence. All full-text papers were independently screened (always MBH, in addition to SBH, BA, MM, or PHB). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and if needed, a third author (MM) was consulted to reach a final decision.

Data Extraction (and Synthesis)

Data were extracted into a table format by one reviewer (MBH or BA) and were checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (SBH or PHB). The extracted data included study design, country, participant demographics (age and sex) and clinical characteristics (i.e., ID severity, adaptive level, comorbid diagnosis), rater characteristics (i.e., parent/caregiver, teacher or other), and information about the data analyses/psychometric properties.

The data were summarized for all the studies reporting on each measurement tool, with a narrative synthesis.

Methodological Quality of MH Measures

As the objective was to assess the psychometric properties of the MH measures as they appeared in the studies we identified, we did not assess the quality of the methods in the included studies themselves. Originally, we planned to use the COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist (Mokkink et al., 2018) to evaluate the psychometric properties of identified MH measures. However, we found that this tool was more suitable for assessing outcome studies. Accordingly, we chose to use the EFPA review model for the description and evaluation of psychological and educational tests (European Federation of Psychologists' Association (EFPA), 2013) to guide the assessment of the psychometric properties (Table 1). More specifically, reliability (i.e., internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and interrater reliability) and validity (i.e., criterion validity, content validity, and construct validity) were evaluated by means of the interpretation guidelines from the EFPA review model (European Federation of Psychologists' Association (EFPA), 2013) using a four-point scale (0 = not reported/not applicable; 1 = inadequate; 2 = adequate; 3 = excellent/good). We did not evaluate the measure’s reported norms. See Table 1 for more information. This quality assessment was independently conducted by MBH and SBH for 20 randomly chosen studies reporting psychometric statistics. The interrater reliability of these assessments showed an excellent degree of correspondence (r = 0.92) for the sum scores. Due to a high degree of correspondence in scoring, the remaining articles/studies (n = 29) were then randomly distributed between MBH and SBH. If uncertainty in scoring arose, this was discussed between MBH and SBH; if needed, a third author (MM) was consulted before an agreement was reached.

All studies pertaining to each individual measurement tool were then included in the overall assessment of each measure, allowing the authors to establish the weight of evidence for each measure in turn.

Results

Literature Selection

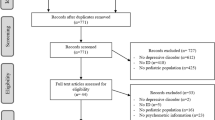

The literature searches resulted in 22,692 unique references. We excluded 20,069 after screening titles and abstracts, and we assessed 774 full-text articles, of which 725 were excluded (see Appendix III for excluded studies with exclusion reasons). A total of 49 trials/papers were ultimately included. Details of the study selection process and reasons for exclusion are provided in Fig. 1. There were very few cases where a third reviewer (MM) was required to resolve disagreements. We focused on assessment instruments of MH for children and adolescents with chronological ages of 4–20 years. Some assessment tools had additional supporting data for older age groups, but this information was not included in the current review.

MH Instruments

A total of 49 papers reporting on 10 instruments for assessing MH problems among children and adolescents with ID were identified and included (Aman et al., 1996; Baraldi et al., 2013; Borthwick-Duffy et al., 1997; Bostrom et al., 2016; Braga et al., 2018; Brereton et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2002; Chadwick et al., 2000; Clarke et al., 2003; Coe et al., 1999; Dekker et al., 2002a, 2002b, 2002c; Dieleman et al., 2018; Douma et al., 2006; Einfeld & Tonge, 1995; El-Keshky & Emam, 2015; Embregts et al., 2010; Emerson, 2005; Esbensen et al., 2018; Freund & Reiss, 1991; Hassiotis & Turk, 2012; Hastings et al., 2001; Haynes et al., 2013; Jacola et al., 2014; Kaptein et al., 2008; Koskentausta & Almqvist, 2004; Koskentausta et al., 2004; Marshburn & Aman, 1992; Masi et al., 2002; Matson et al., 1984; Mircea et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2020; Norris & Lecavalier, 2011; Oliver et al., 2003; Oubrahim & Combalbert, 2019; Reiss & Valenti-Hein, 1994; Rice et al., 2018; Rojahn & Helsel, 1991; Rojahn et al., 2010; Sansone et al., 2012; Taffe et al., 2007; Tasse & Lecavalier, 2000; Tasse et al., 1996; Tonge et al., 1996; van Lieshout et al., 1998; Wallander et al., 2006; Wolf, 1981; Wright, 2010) (see Tables 2 and 3). Of these instruments, seven were aimed for the intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) population (i.e., ID instruments), while three instruments were not originally designed or aimed for use in this population (i.e., non-ID instruments) (Table 3).

The included assessment instruments were intended to screen for a relatively broad spectrum of problems, so-called broadband assessment instruments. The frequency, severity and duration of target behaviors were most often used to measure MH problems. Four papers gave a first report of the development or adaptation of a new instrument (Challenging Behavior Interview [CBI] (Oliver et al., 2003); Developmental Behavior Checklist [DBC] (Einfeld & Tonge, 1995); Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form [NCBRF] (Aman et al., 1996); Reiss Scales for Children’s Dual Diagnosis [Reiss] (Reiss & Valenti-Hein, 1994); Well-Being in Special Education Questionnaire [WellSEQ] (Bostrom et al., 2016)).

Overall, the identified instruments reported their development/framework through a widely defined bottom-up approach (i.e., descriptive-empirical approach) based on specific descriptors of children’s functioning. These individual symptoms (i.e., items) were either based on other existing questionnaires (e.g., the NCBRF was adapted from the Child Behavior Rating Form, and the SDQ was adapted from the Rutter Questionnaire) and/or based on a literature review of the field, expert consultation, or case files from IDD services (i.e., the ID instruments). The ASEBA and the latest version (e.g., Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL]) specifically reported six additional subscales based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The ASEBA (i.e., CBCL, Teacher Rating Form [TRF], and Youth Self Report [YSR]) was the most comprehensive measure identified in terms of the number of items (i.e., 120 items) compared to the other measures (mean number of 53 items). The SDQ, on the other hand, lacked DSM-oriented subscales.

It is noteworthy that the majority of the instruments were proxy or informant-based measures with the exception of the WellSEQ (Bostrom et al., 2016), an ID instrument, and the ASEBA and SDQ, both non-ID instruments, which also offered a youth self-report form. Five papers reported using the youth self-report form (ASEBA: (Douma et al., 2006); SDQ: (Embregts et al., 2010; Emerson, 2005; Haynes et al., 2013); WellSEQ: (Bostrom et al., 2016). The other papers reported using parent/primary caregiver, teacher, and (health) care staff as informants (Table 2). All identified studies/papers reporting on instruments were in the English language. Moreover, all instruments were originally developed in English, with the exception of the WellSEQ (Bostrom et al., 2016), which was developed in the Swedish language. However, the majority of the identified measures had one or more studies that reported psychometric properties for non-English versions, with the exception of the ABC (Aman & Singh, 1986) and Behavior Problem Checklist (BPC) (Quay & Peterson, 1975, 1983) (see Table 2).

We found that most papers used the ASEBA (11 papers) followed by the DBC (10 papers) and further followed by, in descending order, the SDQ (7 papers), ABC/NCBRF (6 papers each), Behavior Problems Inventory-01 (BPI-01) (4 papers), BPC (3 papers), and CBI/Reiss/WellSEQ (1 paper each). For seven of the measures, the researcher by whom it was developed was involved in its evaluation (ABC: Brown et al., 2002; Marshburn & Aman, 1992; BPI-01: Baraldi et al., 2013; Mircea et al., 2010; Rojahn et al., 2010; CBI: Oliver et al., 2003; DBC: Brereton et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2003; Dekker et al., 2002a, b, c; Einfeld & Tonge, 1995; Taffe et al., 2007; Tong et al., 1996; NCBRF: Aman et al., 1996; Tasse et al., 1996; Rojahn et al., 2010; Tasse & Lecavalier, 2000; Reiss: Reiss & Valentin-Hein, 1994; WellSEQ: Bostrom et al., 2016).

In relation to participant samples, the vast majority included mixed samples of people with ID with the exception of pure syndrome-specific samples in alphabetical order: i) Down syndrome (Coe et al., 1999; Dieleman et al., 2018; Esbensen et al., 2018; Jacola et al., 2014); ii) Fragile X (Sansone et al., 2012), iii) Prader-Willi syndrome (van Lieshout et al., 1998) and iiii) Williams syndrome (Braga et al., 2018). The majority of the studies included samples, in which the major proportion were reported with up to a moderate ID level, with the exception of a few studies reporting a high proportion of likely more severe ID (Chadwick et al., 2000; Hastings et al., 2001; Oliver et al., 2003). It should be noted, as shown in Table 2, that in general, very few studies reported formal IQ data and/or data concerning participants’ adaptive function level. FSIQ was reported only with the ABC (two papers), ASEBA (five papers), and BPI-01/NCBRF (one paper each). In relation to sex, overall, the papers reported on samples consisting of a higher proportion of boys, with the exception of five studies (ASEBA: Braga et al., 2018; Jacola et al., 2014); BPI-01 (Mircea et al., 2010; Oubrahim & Combalbert, 2019); NCBRF: (Mircea et al., 2010)). Moreover, population-based samples were reported by six papers (ASEBA: (Wallander et al., 2006); DBC: (Dekker et al., 2002a, b, c; Einfeld & Tonge, 1995; Taffe et al., 2007; Tonge et al., 1996); SDQ: (Emerson, 2005)), and special education/school samples were reported by 19 papers (ABC: Brown et al., 2002; Chadwick et al., 2000; Marshburn & Aman, 1992); ASEBA: (Dekker et al., 2002a, b, c; Douma et al., 2006; Wright, 2010); BPC: (Matson et al., 1984; Wolf, 1981); BPI-01: (Rojahn et al., 2010); CBI: (Dekker et al., 2002a, b, c; Oliver et al., 2003); DBC: (Hastings et al., 2001); NCBRF: (Norris & Lecavalier, 2011; Rojahn et al., 2010; Tasse & Lecavalier, 2000); SDQ: (El-Keshky & Emam, 2015; Haynes et al., 2013; Kaptein et al., 2008); WellSEQ: (Bostrom et al., 2016)). The remaining papers reported on some form of community samples, specific syndrome samples (as noted above) or patient samples (Table 2). Regarding sample sizes, 30 papers reported a sample size of 100 participants or more, as shown in Table 2.

Methodological Quality of MH Measures

The quality assessment of the psychometric properties in terms of reliability and validity of the MH measures as they appeared in the papers/studies indicated overall summary scores ranging from 0% (i.e., the relevant properties not reported; (Tasse & Lecavalier, 2000)) to 89% (i.e., the majority of the properties documented in large sample and found to be good/excellent properties; (Einfeld & Tonge, 1995)) (Table 4).

All measures except the BPC and CBI were supported by evidence regarding internal consistency, and in general, the internal consistency of the scales across instruments was adequate (i.e., 0.70–0.79) to good/excellent (≥ 0.80) (see Table 1 and Method for more details). Evidence of interrater reliability was found for all measures with the exception of the CBI and Reiss; however, with few exceptions (i.e., BPI-01 and DBC), the evidence indicated inadequate agreement (i.e., < 0.60) in most instances. In terms of consistency over time, although there was no evidence found (i.e., it was not examined/reported) for the CBI, Reiss, and SDQ, all other measures were supported by adequate (i.e., 0.60-0.69) or good/excellent test–retest reliability (i.e., ≥ 0.70) with the exception of the BPC (i.e., inadequate reliability: ≤ 0.60). However, studies examining test–retest reliability were inadequate in terms of small sample sizes (N < 100), although there were some exceptions (ASEBA: Dekker et al., 2002a, b, c; Wallander et al., 2006); DBC: (Einfeld & Tonge, 1995)).

Regarding the validity of the measures, little evidence of criterion-related validity and content validity was found. Most of the studies used clinician-rated diagnosis/caseness as a criterion or examined meaningful/hypothesized group differences in subscale scores across diagnostic groups (ABC: (Rojahn & Helsel, 1991); ASEBA: (Douma et al., 2006; Koskentausta et al., 2004); DBC: (Brereton et al., 2006; Clarke et al., 2003; Dekker et al., 2002a, b, c; Einfeld & Tonge, 1995; Hassiotis & Turk, 2012; Koskentausta & Almqvist, 2004); NCBRF: (Norris & Lecavalier, 2011; Reiss & Valenti-Hein, 1994)). Regarding the SDQ, Emerson (2005) reported correspondence between subscale scores and diagnoses from a diagnostic interview (Development and Well-Being Assessment; (Goodman et al., 2000) that had not been validated for persons with ID. We identified more reports of criterion-related validity (i.e., clinician-rated diagnosis/caseness/hypothesized group differences in subscale scores across diagnostic groups) that were reported as good/excellent (i.e., ≥ 0.35) for the DBC compared to the other measures, and no evidence on this aspect for the BPC, BPI-01, CBI, and WellSEQ (Table 4). Evidence of content validity was reported for most of the ID measures (CBI, DBC, NCBRF, Reiss, and WellSEQ) and for one non-ID measure (SDQ).

The majority of measures were supported by evidence of construct validity in terms of correlations between instruments assessing similar constructs, with the exception of the BPC and Reiss, where no evidence was found. Regarding the non-ID instruments, evidence of construct validity was reported for the ASEBA and SDQ, where ID instruments were the most commonly used benchmarks (in alphabetical order: ABC, BPI-01, DBC, NCBRF, and Psychopathology Instrument for Mentally Retarded Adults) (see Table 2). Likewise, evidence of construct validity was reported for the ID instruments, where the other ID measures were most often used as benchmarks (in alphabetical order: ABC, BPI-01, DBC, and NCBRF) (Tables 2 and 4). In relation to sample sizes and reported evidence of construct validity, the NCBRF was examined in the most studies that were large enough (N > 200 in four studies), followed by the BPI-01 and DBC (both had N > 200 in two studies and N = 100–200 in one study), ASEBA (N > 200 in two studies), and SDQ (N > 200 in one study). Moreover, papers/studies examining the CBI and WellSEQ both reported evidence of construct validity using inadequate sample sizes (N < 100).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used with all measures except the CBI and WellSEQ, and these studies most often used principal component analysis (Table 2). The measure that had the factor structure (FS) examined in the most papers/studies was the ABC (five studies), followed by the DBC (four studies), NCBRF (three studies), BPI-01 (two studies), and ASEBA/BPC/Reiss (all one study each). In regard to the ABC, all studies except one reported adequate to good/excellent FS (Tables 2 and 4). In addition, Sansone et al. (2012) reported an inadequate FS in a syndrome-specific sample (Fragile X) and suggested an alternative FS, with one factor unchanged (inappropriate speech), four modified (irritability, hyperactivity, lethality/withdrawal, and stereotypy), and a new social avoidance factor. Borthwick-Duffy et al. (1997) reported an adequate FS for ASEBA–CBCL only for the broadband internalizing and externalizing factors, although the analysis was based on an inadequate sample size (N < 100). An inadequate FS was also reported for the BPC in a large study (Matson et al., 1984). The FS of the BPI-01 using confirmatory FA (CFA) was found to be good/excellent in one large study in a specialized ID institution in France and inadequate in a large special education sample in the US (Table 4). In regard to the DBC, all studies were large; most studies reported an adequate FS, and one reported a good/excellent FS, all by means of EFA (Table 4). Regarding the NCBRF, good/excellent FS was reported in one large study among outpatients using EFA, adequate FS in a large CFA study among special education students/outpatients, and inadequate FS in another large CFA study among special education students (Table 4). The only study that examined the Reiss was large and reported a good/excellent FS (Reiss & Valenti-Hein, 1994). The FS of the SDQ in terms of the broader internalizing and externalizing subscales (alongside the fifth prosocial subscale) was found to be adequate in one large study among students from Saudi Arabia and Oman using CFA (El-Keshky & Emam, 2015) and inadequate in a smaller sample (N = 128) of students from Australia examining the original five-factor structure (Table 4).

In relation to self-report, the ASEBA–YSR and WellSEQ were the only measures with evidence of reported adequate aspects of reliability and an adequate aspect of validity (see Table 4). However, the evidence was not confirmed by supporting studies.

Based on the EFPA review model (see Method), all studies examining each individual measurement tool were then included in the overall assessment of each measure (Table 5), allowing us to establish the weight of evidence for each measure.

As seen in Table 5, the DBC was the only measure with at least two aspects of reliability (i.e., test–retest and interrater) assessed as good/excellent by two studies, in addition to all validity aspects assessed with evidence of good/excellent with more than one supporting study in relation to criterion and construct validity (convergent validity). The ABC, NCBRF and BPI-01 had two or more aspects of reliability and validity assessed as good/excellent, but at least two aspects of reliability and validity, each in the good/excellent range, were not confirmed by a supporting study. The non-ID measure ASEBA had two aspects of reliability assessed as good/excellent, as reported by two studies, but only convergent validity was reported as good/excellent by supporting studies, and no other validity aspect was assessed in the good/excellent range. The remaining four measures (Reiss, CBI, SDQ, WellSEQ) had no aspects of reliability assessed as good/excellent with supporting studies, although the Reiss had two aspects of validity assessed as good/excellent with no supporting study, and comparably, the CBI/SDQ/WellSEQ had one aspect of validity assessed as good/excellent. The BPC had no aspect of reliability or validity assessed as good/excellent or adequate.

Furthermore, the average psychometric quality, based on the sum score (maximum possible quality score = 35; Table 4) for each measurement tool as they were scored during the quality assessment of the studies, indicated relatively large differences. In general, quality for the ID measures (M = 12.03, SD = 7.30) was better than for the non-ID measures (M = 6.64, SD = 5.16) (Table 5). Moreover, the average psychometric quality (Table 5) based on the quality assessment sum score was quite similar among the different ID measures, although the number of studies reporting psychometric properties for each measure greatly varied (e.g., DBC in 10 papers versus WellSEQ in 1 paper). Therefore, when examining, for instance, the ID measures Reiss and WellSEQ with a relatively high average psychometric quality score, it is important to be aware that the documentation was very limited, as shown in the associated standard deviation values in Table 5.

Discussion

Careful assessment of MH is recommended among all people with ID due to the high vulnerability of this population for developing MH disorders. Our systematic review on the measurement properties of general MH instruments used with children and adolescents with ID identified documentation for ten instruments. The instruments can be divided into two main groups: instruments specifically developed or adapted for the ID population (ID instruments: Aberrant Behavior Checklist [ABC], Behavior Problems Inventory [BPI-01], Challenging Behavior Inventory [CBI], Developmental Behavior Checklist [DBC], Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form [NCBRF], Reiss Scales for Children’s Dual Diagnosis [Reiss], and Well-Being in Special Education Questionnaire [WellSEQ]) and instruments developed for the general child population (non-ID instruments: Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment [ASEBA], Behavior Problem Checklist [BPC educational setting], and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ]). All identified instruments were screening measures to be used in an initial assessment of MH problems. Of the identified instruments, only the ASEBA had DSM-oriented subscales. The other instruments, including the additional ASEBA subscales, were based on specific descriptors of children’s functioning (e.g., from a literature review, case files, expert consultations, or other existing measures), which were then refined through empirical results and most often from principal component analysis.

The main finding from the present systematic review was consistently better documentation of reliability and validity in terms of higher overall average quality assessment (sum) scores for the ID instruments than for the non-ID instruments. Overall, there were comparable average quality assessment sum scores among the different ID instruments in situations where we identified measures with the most papers reporting psychometric properties (i.e., ABC, BPI-01, DBC, and NCBRF). For the ID instruments CBI, Reiss, and WellSEQ, the findings were more limited due to very little documentation (i.e., one paper each reporting psychometric properties). Regarding the non-ID instruments, the ASEBA gained a higher overall quality score than the other non-ID instruments (i.e., BPC and SDQ). Nevertheless, the average overall quality score for the ASEBA was lower than that for the ID instruments ABC, BPI-01, DBC, and NCBRF.

When examining the overall assessment of each measure in more detail, the DBC was the only measure with most aspects of reliability (test–retest and interrater) and all aspects of validity (criterion, content, factor structure, and convergent validity) assessed as good/excellent, with more than one supporting study for at least two aspects of reliability and validity. The other ID instruments, the ABC, BPI-01, and NCBRF, had several aspects of reliability and validity assessed as good/excellent but fewer supporting studies than the DBC. Regarding the non-ID instruments, the ASEBA had two aspects of reliability (internal consistency and test–retest) assessed as good/excellent by two studies, however, with the exception of convergent validity, other validity aspects were not assessed as good/excellent. There was less evidence for SDQ suitability in terms of reliability and validity compared to ASEBA suitability. Based on the documentation identified for the BPC (i.e., no aspects assessed as good/excellent or adequate), we would not recommend the continued use of this instrument in its current form for this population, and this is probably reflected by the most recent identified study using the BPC being 22 years old (Coe et al., 1999). Regarding documentation of construct validity, in terms of correlations between instruments measuring similar constructs (convergent validity), most of the studies using non-ID measures (e.g., the ASEBA) used ID instruments as benchmarks. Moreover, documentation of construct validity in terms of factor structure was limited for both the non-ID measures ASEBA and SDQ, and these analyses favored the use of the broadband scales (i.e., internalizing and externalizing scales) over the more specific subscales.

It is important to emphasize that the vast majority of studies reporting psychometric properties in the present systematic review involved samples primarily consisting of children and adolescents with a borderline to moderate ID level. This finding is consistent with the findings from a relatively recent systematic review among people of all age groups with severe or profound ID, which found no eligible studies (i.e., at least 70% of the sample within a severe/profound ID level) reporting psychometric properties of measures for children and adolescents (Flynn et al., 2017). Whether the various instruments are suitable for children and adolescents with severe and profound ID is therefore largely unknown and should be investigated in future studies. Furthermore, regarding the ID status of the participants, the majority of the studies in the present systematic review used an administrative operationalization of ID status (e.g., school placement). Accordingly, with few exceptions, a formal IQ assessment or adaptive assessment was not conducted or reported. An implication of this is that the ID concept/condition was loosely defined; therefore, we cannot rule out that the studies included children and adolescents who would not qualify for a formal ID diagnosis.

The perspective of the child or adolescent in terms of self-report measures was very limited, as identified in the present review. The vast majority of studies used informant-based measures completed by parents/caregivers, teachers and (health) care staff. We identified three self-report measures (i.e., the ASEBA, SDQ, and WellSEQ), in which the non-ID measure ASEBA–YSR and the ID measure WellSEQ reported very limited data indicating adequate reliability and validity mainly in samples with mild ID (Bostrom et al., 2016; Douma et al., 2006). However, the evidence was not confirmed by supporting studies. Further development and refinement of the usage of self-reporting, if possible, will be an important development area for the field. The use of multiple informants, including the youths themselves, is recommended, as individuals who have difficulties conveying information on symptoms verbally may display these in varying ways, and no single informant is likely to have a complete overview of another person’s life (Stratis & Lecavalier, 2015). The heterogeneity of ID suggests that a single measure able to identify MH problems across the ID population is unlikely to be constructed in the near future, thereby underscoring the importance of individualized, multimodal and multi-informant approaches to assessment (Halvorsen et al., 2022). MH assessment is recommended by the use of standardized measures where the clinician also considers the strengths and weaknesses of the instrument, which has been the focus of the current systematic review.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the strengths and limitations of the study. To our knowledge, this review is the first recent systematic review to examine the psychometric properties of measurement tools used to assess general MH problems in children and adolescents across the whole ID spectrum. We did not limit the review to ID instruments only, as the field (clinic and research community) is characterized by the use of ID and non-ID instruments. We limited the review to studies using mainly children/adolescent samples and did not include findings from studies that used mixed-age samples that also included adults above 25 years of age. We chose to do so because a mixed age range than includes adults can provide findings that are not necessarily transferable to children. Additionally, studies that reported only prevalence rates (or instrument mean scores of MH problems/disorders) in children and adolescents with ID were not eligible because they did not report psychometric properties. We did not evaluate the measure's norms as norming data for the measures was only reported by two of the studies (ABC: Marshburn & Aman, 1992; NCBRF; Tasse et al., 1996), and norms for measures published in manuals through publishers were not included. Another limitation of the study was that we did not calculate inter-rater reliability for the full-text review and data extraction. We did however calculate inter-rater reliability for the quality assessment for 20 randomly chosen studies reporting psychometric properties, and these assessments showed an excellent degree of correspondence (r = 0.92) for the sum scores. Finally, the vast majority of the identified measures had one or more studies that reported psychometric properties for the non-English versions. It is important for future studies to establish linguistic equivalence and to determine consistency of the measure’s psychometric properties.

Conclusion

This systematic review contributes to the field of MH assessment among children and adolescents with ID by examining the psychometric properties of measurement tools used to assess general MH problems in children and adolescents with a borderline to moderate level of ID. Our findings support the use of standardized ID instruments as the first choice in an initial assessment. Very few self-report measures have been developed for children and adolescents with ID, and very few studies have examined their suitability. How to integrate the youths’ perspectives in assessing MH problems is an important focus area in the future.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: an integrated system of multi-informant assessment. ASEBA.

Aman, M. G., & Singh, N. N. (1986). Aberrant behavior checklist manual. Slosson Educational Publishers.

Aman, M. G., Tasse, M. J., Rojahn, J., & Hammer, D. (1996). The Nisonger CBRF: A child behavior rating form for children with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 17(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-4222%2895%2900039-9

Baraldi, G. S., Rojahn, J., Seabra, A. G., Carreiro, L. R. R., & Teixeira, M. C. T. V. (2013). Translation, adaptation, and preliminary validation of the Brazilian version of the Behavior Problems Inventory (BPI-01). Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 35(3), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2237-60892013000300007

Brinkley, J., Nations, L., Abramson, R. K., Hall, A., Wright, H. H., & Gabriels, R.. (2007). Factor analysis of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1949–1959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0327-3

Borthwick-Duffy, S. A., Lane, K. L., & Widaman, K. F. (1997). Measuring problem behaviors in children with mental retardation: Dimension and predictors. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 18(6), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222%2897%2900020-6

Bostrom, P., Johnels, J. A., Thorson, M., & Broberg, M. (2016). Subjective mental health, peer relations, family, and school environment in adolescents with intellectual developmental disorder: A first report of a new questionnaire administered on tablet PCs. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 9(4), 207–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2016.1186254

Braga, A. C., Carreiro, L. R. R., Tafla, T. L., Ranalli, N. M. G., Silva, M., Honjo, R. S., Kim, C. A., & Teixeira, M. (2018). Cognitive and behavioral profile of Williams Syndrome toddlers. Codas, 30(4), e20170188. https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/20182017188

Brereton, A. V., Tonge, B. J., & Einfeld, S. L. (2006). Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 36(7), 863–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0125-y

Brown, E. C., Aman, M. G., & Havercamp, S. M. (2002). Factor analysis and norms for parent ratings on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Community for young people in special education. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 23(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222%2801%2900091-9

Chadwick, O., Piroth, N., Walker, J., Bernard, S., & Taylor, E. (2000). Factors affecting the risk of behaviour problems in children with severe intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 44(2), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00255.x

Clarke, A., Tonge, B., Einfeld, S. L., & Mackinnon, A. (2003). Assessment of change with the Developmental Behaviour Checklist. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(3), 210–212. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00470.x

Coe, D. A., Matson, J. L., Russell, D. W., Slifer, K. J., Capone, G. T., Baglio, C., & Stallings, S. (1999). Behavior problems of children with Down syndrome and life events. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023044711293

Dekker, M. C., Koot, H. M., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2002a). Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 43(8), 1087–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00235

Dekker, M. C., Nunn, R. J., Einfeld, S. E., Tonge, B. J., & Koot, H. M. (2002b). Assessing emotional and behavioral problems in children with intellectual disability: Revisiting the factor structure of the Developmental Behavior Checklist. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(6), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021263216093

Dekker, M. C., Nunn, R., & Koot, H. M. (2002c). Psychometric properties of the revised Developmental Behaviour Checklist scales in Dutch children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 46(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00353.x

Dieleman, L. M., De Pauw, S. S., Soenens, B., Van Hove, G., & Prinzie, P. (2018). Behavioral problems and psychosocial strengths: Unique factors contributing to the behavioral profile of youth with Down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 123(3), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-123.3.212

Douma, J. C., Dekker, M. C., Verhulst, F. C., & Koot, H. M. (2006). Self-reports on mental health problems of youth with moderate to borderline intellectual disabilities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(10), 1224–1231. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000233158.21925.95

Edelbrock, C. S. (1985). Child behavior rating form. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21, 835–837.

Einfeld, S. L., Ellis, L. A., & Emerson, E. (2011). Comorbidity of intellectual disability and mental disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 36(2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250.2011.572548

Einfeld, S. L., & Tonge, B. J. (1995). The Developmental Behavior Checklist: The development and validation of an instrument to assess behavioral and emotional disturbance in children and adolescents with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(2), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02178498

Einfeld, S. L., & Tonge, B. J. (1992). Manual for the Developmental behviour Checklist. Clayton, Melbourne and Sydney: Monash University for Developmental Psychiatry and School of Psychiatry, University of New South.

El-Keshky, M., & Emam, M. (2015). Emotional and behavioural difficulties in children referred for learning disabilities from two Arab countries: A cross-cultural examination of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.039

Embregts, P. J., du Bois, M. G., & Graef, N. (2010). Behavior problems in children with mild intellectual disabilities: An initial step towards prevention. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(6), 1398–1403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.020

Emerson, E. (1998). Working with people with challenging behaviour. In E. Emerson, C. Hatton, J. Bromley, & A. Caine (Eds.), Clinical Psychology and people with intellectual disabilities (pp. 127–153). Wiley.

Emerson, E. (2005). Use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to assess the mental health needs of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 30(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250500033169

Esbensen, A., Hoffman, E., Shaffer, R., Chen, E., Patel, L., & Jacola, L. (2018). Reliability of parent report measures of behaviour in children with down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12533

Flynn, S., Vereenooghe, L., Hastings, R. P., Adams, D., Cooper, S. A., Gore, N., Hatton, C., Hood, K., Jahoda, A., Langdon, P. E., McNamara, R., Oliver, C., Roy, A., Totsika, V., & Waite, J. (2017). Measurement tools for mental health problems and mental well-being in people with severe or profound intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.006

Freund, L. S., & Reiss, A. L. (1991). Rating problem behaviors in outpatients with mental retardation: Use of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 12(4), 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-4222%2891%2990037-S

Goodman, R., Ford, T., Richards, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). The Development and Well-Being Assessment: Description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(5), 645–655.

Halvorsen, M. B. , Kildahl., A.N., & Helverschou, S. B. (2022). Measuring Comorbid Psychopathology-In Press. In M. Sturmey (Ed.), Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Springer.

Halvorsen, M., Mathiassen, B., Myrbakk, E., Brøndbo, P. H., Sætrum, A., Steinsvik, O. O., & Martinussen, M. (2019). Neurodevelopmental correlates of behavioural and emotional problems in a neuropaediatric sample. Research In Developmental Disabilities, 85, 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.11.005

Hassiotis, A., & Turk, J. (2012). Mental health neds in adolescents with intellectual disabilities: Cross-sectional survey of a service sample. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25(3), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2011.00662.x

Hastings, R. P., Brown, T., Mount, R. H., & Cormack, K. F. (2001). Exploration of psychometric properties of the developmental behavior checklist. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 31(4), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010668703948

Haynes, A., Gilmore, L., Shochet, I., Campbell, M., & Roberts, C. (2013). Factor analysis of the self-report version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in a sample of children with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(2), 847–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2012.11.008

Jacola, L. M., Hickey, F., Howe, S. R., Esbensen, A., & Shear, P. K. (2014). Behavior and adaptive functioning in adolescents with Down syndrome: Specifying targets for intervention. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(4), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2014.920941

Kaat, A. J, Lecavalier, L, & Aman, M. G. (2014). Validity of the aberrant behavior checklist inchildren with autism spectrum disorder. Journal Of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 1103–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1970-0

Kaptein, S., Jansen, D., Vogels, A., & Reijneveld, S. (2008). Mental health problems in children with intellectual disability: Use of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00978.x

Koskentausta, T., & Almqvist, F. (2004). Developmental Behaviour Checklist (DBC) in the assessment of psychopathology in Finnish children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250410001662883

Koskentausta, T., Iivanainen, M., & Almqvist, F. (2004). CBCL in the assessment of psychopathology in Finnish children with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(4), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2003.12.001

Lin, J. D., Hu, J., Yen, C. F., Hsu, S. W., Lin, L. P., Loh, C. H., Chen, M. H., Wu, S. R., Chu, C. M., & Wu, J. L. (2009). Quality of life in caregivers of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities: Use of WHOQOL-BREF survey. Research in Developmental Disability, 30(6), 1448–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.005

Marshburn, E. C., & Aman, M. G. (1992). Factor validity and norms for the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in a community sample of children with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(3), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01048240

Masi, G., Brovedani, P., Mucci, M., & Favilla, L. (2002). Assessment of anxiety and depression in adolescents with mental retardation. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 32(3), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017908823046

Matson, J. L., Epstein, M. H., & Cullinan, D. (1984). A factor analytic study of the Quay-Peterson scale with mentally retarded adolescents. Education & Training of the Mentally Retarded, 19(2), 150–154.

Mircea, C. E., Rojahn, J., & Esbensen, A. J. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of Romanian translations of the Behavior Problems Inventory-01 and the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 3(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315860903520515

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mokkink, L. B., de Vet, H. C. W., Prinsen, C. A. C., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., & Terwee, C. B. (2018). COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4

Munir, K. M. (2016). The co-occurrence of mental disorders in children and adolescents with intellectual disability/intellectual developmental disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000236

Murray, C. A., Hastings, R. P., & Totsika, V. (2020). Clinical utility of the parent-reported strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a screen for emotional and behavioural difficulties in children and adolescents with intellectual disability. The British Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.224

Norris, M., & Lecavalier, L. (2011). Evaluating the validity of the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form-Parent Version. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2894–2900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.015

Ono, Y. (1996). Factor validity and reliability for the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-community in a Japanese population with mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 17, 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-4222(96)00015-7

Oliver, C., McClintock, K., Hall, S., Smith, M., Dagnan, D., & Stenfert-Kroese, B. (2003). Assessing the severity of challenging behaviour: Psychometric properties of the Challenging Behaviour Interview. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00145.x

Oubrahim, L., & Combalbert, N. (2019). Behaviour problems in people with intellectual disabilities: Validation of the French version of the behaviour problems inventory - short form. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12612

Quay, H. C., & Peterson, D. R. (1975). Manual for the behavior problem checklist. Unpublished manuscript.

Quay, H. C., & Peterson, D. R. (1983). Revised behavior problem checklist. Herbert C. Quay.

Reiss, S., & Valenti-Hein, D. (1994). Development of a psychopathology rating scale for children with mental retardation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.1.28

European Federation of Psychologists' Association (EFPA). (2013). EFPA review model for the description and evaluation of psychological tests: Test review form and notes for reviewers, v 4.2.6. EFPA.

Rice, L., Emerson, E., Gray, K., Howlin, P., Tonge, B., Warner, G., & Einfeld, S. (2018). Concurrence of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and developmental behaviour checklist among children with an intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(2), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12426

Rojahn, J., & Helsel, W. J. (1991). The Aberrant Behavior Checklist with children and adolescents with dual diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 21(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02206994

Rojahn, J., Rowe, E. W., Macken, J., Gray, A., Delitta, D., Booth, A., & Kimbrell, K. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the Behavior Problems Inventory-01 and the Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form with children and adolescents. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 3(1), 28–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315860903558168

Sansone, S. M., Widaman, K. F., Hall, S. S., Reiss, A. L., Lightbody, A., Kaufmann, W. E., Berry-Kravis, E., Lachiewicz, A., Brown, E. C., & Hessl, D. (2012). Psychometric study of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in Fragile X Syndrome and implications for targeted treatment. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1377–1392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1370-2

Siegfrid, L. W. K. (2000). A study of the reliability and validity of the Chinese version Aberrant Behavior Checklist (M. Sc. Thesis). The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong. Retrieved from http://theses.lib.polyu.edu.hk/handle/20

Stratis, E. A., & Lecavalier, L. (2015). Informant agreement for youth with autism spectrum disorder or intellectual disability: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder, 45(4), 1026–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2258-8

Taffe, J. R., Gray, K. M., Einfeld, S. L., Dekker, M. C., Koot, H. M., Emerson, E., Koskentausta, T., & Tonge, B. J. (2007). Short form of the Developmental Behaviour Checklist. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017%282007%29112%5B31:SFOTDB%5D2.0.CO;2

Tasse, M. J., Aman, M. G., Hammer, D., & Rojahn, J. (1996). The Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form: Age and gender effects and norms. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 17(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-4222%2895%2900037-2

Tasse, M. J., & Lecavalier, L. (2000). Comparing parent and teacher ratings of social competence and problem behaviors. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 105(4), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017%282000%29105%3C0252:CPATRO%3E2.0.CO;2

Tonge, B., Einfeld, S., Krupinski, J., Mackenzie, A., McLaughlin, M., Florio, T., & Nunn, R. (1996). The use of factor analysis for ascertaining patterns of psychopathology in children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 40(3), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.1996.tb00623.x

van Lieshout, C. F., de Meyer, R. E., Curfs, L. M., Koot, H. M., & Fryns, J. P. (1998). Problem behaviors and personality of children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 23(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/23.2.111

Wallander, J. L., Dekker, M. C., & Koot, H. M. (2006). Risk factors for psychopathology in children with intellectual disability: A prospective longitudinal population-based study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(4), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00792.x

Wolf, T. M. (1981). Measures of deviant behavior, activity level, and self-concept for educable mentally retarded-emotionally disturbed students. Psychological Reports, 48(3), 903–910. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1981.48.3.903

World Health Organization. (2010). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th Rev.). WHO.

Wright, J. A. (2010). The Impact of Mental Health Issues on Students with Mental Retardation: The Relationship of Teacher Report of Symptoms, Adaptive Functioning, and School Outcomes for Adolescents with Mild Mental Retardation University of Kentucky]. Ph.D. https://media.proquest.com/media/hms/ORIG/1/csGxI?_s=rf5eRID80tecRAuNr7fv8nPr4QM%3D#view=FitV

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Emeritus Professor Michael G. Aman for commenting on the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway. Funding was supported by Helse Nord RHF [Grant No. HNF1525-20] and Marianne Berg Halvorsen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MBH had the idea for the article. BA performed the literature search. All the authors contributed in the data analysis. MBH drafted the article. All authors critically revised the work and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix I PRISMA 2020 Checklist

Appendix II Search strategies

Date of search: 21st of February 2020

Date of updated search 13th of March 2021. The search was for the outcome measures included from the 2020 search, in Ovid databases limited to publication date since the first search.

Searches for ongoing and unpublished trials 16th of May 2021

Information specialist: Brynhildur Axelsdottir baxelsdottir@gmail.com

Total number of hits from all databases: 31.842

Additional records identified through other sources: 6

Total number of hits after removing duplicates: 20.850

PsycINFO < 1967 to February Week 2 2020 > (Ovid interface)

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | intellectual development disorder/or anencephaly/or crying cat syndrome/or down's syndrome/or adaptive behavior/or cognitive impairment/or fetal alcohol syndrome/or fragile x syndrome/or prader willi syndrome/or rett syndrome/or savants/or williams syndrome/or developmental disabilities/or specific language impairment/or learning disorders/or exp learning disabilities/ |

2 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab |

3 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab |

4 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

5 | mental disorders/or child psychopathology/or adolescent psychopathology/or dual diagnosis/or comorbidity/or exp behavior problems/or behavior disorders/or conduct disorder/or exp disruptive behavior disorders/or emotional disturbances/ |

6 | ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) adj2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)).ti,ab |

7 | ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) adj3 (problem* or disorder*)).ti,ab |

8 | 5 or 6 or 7 |

9 | (childhood birth 12 yrs or adolescence 13 17 yrs).ag |

10 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab,id |

11 | 9 or 10 |

12 | 4 and 8 and 11 |

13 | measurement/or exp psychometrics/or psychological assessment/or behavioral assessment/or cognitive assessment/or "communication and language measures"/or "mental health and illness assessment"/or psychosocial assessment/or structured clinical interview/ |

14 | (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* adj tool*)).ti,ab |

15 | 13 or 14 |

16 | 4 and 8 and 12 |

17 | 15 and 16 |

18 | limit 17 to yr = "1980 -Current" |

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) < 1946 to February 19, 2020 > (Ovid interface)

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | intellectual disability/or cri-du-chat syndrome/or de lange syndrome/or down syndrome/or mental retardation, x-linked/or prader-willi syndrome/or rubinstein-taybi syndrome/or trisomy 13 syndrome/or wagr syndrome/or williams syndrome/or Developmental Disabilities/or exp Learning Disabilities/or Specific Language Disorder/ |

2 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab |

3 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab |

4 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

5 | Mental disorders/or "disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders"/or Child Behavior Disorders/or "Diagnosis, Dual (Psychiatry)"/or Problem Behavior/or "attention deficit and disruptive behavior disorders"/ |

6 | ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) adj2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)).ti,ab |

7 | ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) adj3 (problem* or disorder*)).ti,ab |

8 | 5 or 6 or 7 |

9 | exp Child/or exp Adolescent/or Minors/or exp Pediatrics/ |

10 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab,id |

11 | 9 or 10 |

12 | 4 and 8 and 11 |

13 | exp Psychiatric Status Rating Scales/or psychological tests/or behavior rating scale/or psychometrics/ |

14 | (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* adj tool*)).ti,ab |

15 | 13 or 14 |

16 | 12 and 15 |

17 | limit 16 to yr = "1980 -Current" |

Embase < 1980 to 2020 Week 07 > (Ovid interface)

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | mental deficiency/or mental retardation malformation syndrome/or down syndrome/or de lange syndrome/or fragile x syndrome/or prader willi syndrome/or williams beuren syndrome/or x linked mental retardation/or wagr syndrome/or cat cry syndrome/or developmental disorder/or learning disorder/or language disability/ |

2 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab |

3 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab |

4 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

5 | mental disease/or comorbidity/or behavior disorder/or disruptive behavior/or problem behavior/or conduct disorder/or emotional disorder/ |

6 | ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) adj2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)).ti,ab |

7 | ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) adj3 (problem* or disorder*)).ti,ab |

8 | 5 or 6 or 7 |

9 | exp child/or exp adolescent/or exp adolescence/or exp childhood/or exp pediatrics/ |

10 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab,kw,hw,jx |

11 | 9 or 10 |

12 | 4 and 8 and 11 |

13 | psychologic assessment/or psychologic test/or mental test/or psychological interview/or psychological rating scale/or psychometry/or structured interview/ |

14 | (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* adj tool*)).ti,ab |

15 | 13 or 14 |

16 | 12 and 15 |

Health and Psychosocial Instruments < 1985 to January 2020 > (Ovid interface)

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab |

2 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab |

3 | 1 or 2 |

4 | ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) adj2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)).ti,ab |

5 | ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) adj3 (problem* or disorder*)).ti,ab |

6 | 4 or 5 |

7 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab |

8 | 3 and 6 and 7 |

CINAHL EBSCO

S1 | (MH "De Lange Syndrome") OR (MH "Cri-Du-Chat Syndrome") OR (MH "Down Syndrome") OR (MH "Intellectual Disability + ") OR (MH "Williams Syndrome") OR (MH "WAGR Syndrome") OR (MH "Prader-Willi Syndrome") |

S2 | (MH "Developmental Disabilities") |

S3 | (MH "Learning Disorders + ") |

S4 | TI ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) N3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)) OR AB ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) N3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)) |

S5 | TI (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* N2 syndrome*)) OR AB (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* N2 syndrome*)) |

S6 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 |

S7 | (MH "Mental Disorders") |

S8 | (MH "Diagnosis, Dual (Psychiatry)") |

S9 | (MH "Child Behavior Disorders") |

S10 | (MH "Disruptive Behavior") |

S11 | TI ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) N2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)) OR AB ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) N2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)) |

S12 | TI ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) N3 (problem* or disorder*)) OR AB ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) N3 (problem* or disorder*)) |

S13 | S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 |

S14 | (MH "Adolescence + ") OR (MH "Child") OR (MH "Minors (Legal)") |

S15 | (MH "Pediatrics") |

S16 | TI (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*) OR AB (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*) |

S17 | S14 OR S15 OR S16 |

S18 | S6 AND S13 AND S17 |

S19 | (MH "Psychometrics") OR (MH "Psychological Tests + ") |

S20 | (MH "Measurement Issues and Assessments") |

S21 | (MH "Structured Interview") |

S22 | TI (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* N tool*)) OR AB (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* N tool*)) |

S23 | S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 |

S24 | S18 AND S23 |

S25 | S18 AND S23 |

ERIC EBSCO

S1 | DE "Intellectual Disability" |

S2 | DE "Developmental Disabilities" |

S3 | DE "Learning Disabilities" |

S4 | DE "Down Syndrome" |

S5 | TI ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) N3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)) OR AB ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) N3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)) |

S6 | TI (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* N2 syndrome*)) OR AB (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* N2 syndrome*)) |

S7 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 |

S8 | DE "Mental Disorders" |

S9 | DE "Comorbidity" |

S10 | DE "Multiple Disabilities" |

S11 | DE "Behavior Disorders" |

S12 | TI ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) N2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)) OR AB ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) N2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*)) |

S13 | TI ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) N3 (problem* or disorder*)) OR AB ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) N3 (problem* or disorder*)) |

S14 | S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 |

S15 | DE "Adolescents" OR DE "Early Adolescents" OR DE "Late Adolescents" |

S16 | DE "Children" OR DE "Preadolescents" OR DE "Young Children" |

S17 | DE "Youth" OR DE "Disadvantaged Youth" |

S18 | DE "Pediatrics" |

S19 | TI (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*) OR AB (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*) |

S20 | S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 |

S21 | S7 AND S14 AND S20 |

S22 | DE "Psychological Testing" |

S23 | DE "Psychometrics" |

S24 | DE "Structured Interviews" |

S25 | DE "Measures (Individuals)" |

S26 | DE "Behavior Rating Scales" |

S27 | TI (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* N tool*)) OR AB (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* N tool*)) |

S28 | S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 |

S29 | S21 AND S28 |

Web of Science Ebsco

# 1 TS = ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) NEAR/3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)) 147,112

# 2 TS = (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* NEAR/2 syndrome*)) 30,022

# 3 #2 OR #1167,234

# 4 TS = ((mental* or emotional* or psych*) NEAR/2 (disorder* or disturbance* or ill* or well-being or health* or disease* or abnormal* or patholog* or problem* or condition*))319,377

# 5 TS = ((behavi* or conduct* or anger) NEAR/3 (problem* or disorder*))58,355

# 6 #5 OR #4356,855

# 7 TS = (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*)814,572

# 8 TS = (psychometric* or instrument* or inventor* or self-report* or validat* or validity or reliab* or norm or norms or (measurement* NEAR tool*))659,485

# 9 #8 AND #7 AND #6 AND #35,435

Indexes = SSCI, A&HCI Timespan = 1980–2020

Updated search 13th of March 2021

APA PsycInfo < 2002 to March Week 1 2021 >

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | (nisonger* or aberrant* or reiss or overt or devereux or ((develop* or child*) adj behav* adj checklist*) or (strength* adj2 difficult* adj question*) or (well-being adj2 special*) or (disabilit* adj assessment*) or (challeng* adj behav* adj interview)).ti,ab |

2 | (dbc* or cbcl* or sdq*).ti,ab |

3 | 1 or 2 |

4 | intellectual development disorder/or anencephaly/or crying cat syndrome/or down's syndrome/or adaptive behavior/or cognitive impairment/or fetal alcohol syndrome/or fragile x syndrome/or prader willi syndrome/or rett syndrome/or savants/or williams syndrome/or developmental disabilities/or specific language impairment/or learning disorders/or exp learning disabilities/ |

5 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab |

6 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab |

7 | 4 or 5 or 6 |

8 | (childhood birth 12 yrs or adolescence 13 17 yrs).ag |

9 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab,id |

10 | 8 or 9 |

11 | 7 and 10 |

12 | 3 and 11 |

13 | (202,002* or 202,003* or 202,004* or 202,005* or 202,006*or 202,007*or 202,008* or 202,009* or 202,010* or 202,011* or 202,012* or 202,101* or 202,102* or 202,103*).up |

14 | 12 and 13 |

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily < 2017 to March 09, 2021 >

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | (nisonger* or aberrant* or reiss or overt or devereux or ((develop* or child*) adj behav* adj checklist*) or (strength* adj2 difficult* adj question*) or (well-being adj2 special*) or (disabilit* adj assessment*) or (challeng* adj behav* adj interview)).ti,ab |

2 | (dbc* or cbcl* or sdq*).ti,ab |

3 | 1 or 2 |

4 | intellectual disability/or cri-du-chat syndrome/or de lange syndrome/or down syndrome/or mental retardation, x-linked/or prader-willi syndrome/or rubinstein-taybi syndrome/or trisomy 13 syndrome/or wagr syndrome/or williams syndrome/or Developmental Disabilities/or exp Learning Disabilities/or Specific Language Disorder/ |

5 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab |

6 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab |

7 | 4 or 5 or 6 |

8 | exp Child/or exp Adolescent/or Minors/or exp Pediatrics/ |

9 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab,id |

10 | 8 or 9 |

11 | 7 and 10 |

12 | 3 and 11 |

13 | (2020 feb or 2020 mar or 2020 apr or 2020 may or 2020 jun or 2020 jul or 2020 aug or 2020 sep or 2020 oct or 2020 nov or 2020 dec or 2021 jan or 2021 feb or 2021 mar).dp |

14 | (202,002* or 202,003* or 202,004* or 202,005* or 202,006*or 202,007*or 202,008* or 202,009* or 202,010* or 202,011* or 202,012* or 202,101* or 202,102* or 202,103*).dt |

15 | 13 or 14 |

16 | 12 and 15 |

Embase < 1996 to 2021 Week 09 >

# | Searches | |

|---|---|---|

1 | (nisonger* or aberrant* or reiss or overt or devereux or ((develop* or child*) adj behav* adj checklist*) or (strength* adj2 difficult* adj question*) or (well-being adj2 special*) or (disabilit* adj assessment*) or (challeng* adj behav* adj interview)).ti,ab | |

2 | (dbc* or cbcl* or sdq*).ti,ab | |

3 | 1 or 2 | |

4 | mental deficiency/or mental retardation malformation syndrome/or down syndrome/or de lange syndrome/or fragile x syndrome/or prader willi syndrome/or williams beuren syndrome/or x linked mental retardation/or wagr syndrome/or cat cry syndrome/or developmental disorder/or learning disorder/or language disability/ | |

5 | ((intellectual* or mental* or developmental* or learning* or cognit*) adj3 (disab* or impair* or handicap* or disorder* or subnormal* or deficien* or difficult*)).ti,ab | |

6 | (retard* or rett* or prader willi or fragile X or Crying cat or cri du chat or savants or William* syndrome* or (down* adj2 syndrome*)).ti,ab | |

7 | 4 or 5 or 6 | |

8 | exp child/or exp adolescent/or exp adolescence/or exp childhood/or exp pediatrics/ | |

9 | (child* or kid or kids* or minors* or juvenil* or adoles* or youth* or youngster* or teen* or preteen* or boy or boys* or girl* or pediatr* or paediatr*).ti,ab,kw,hw,jx | |

10 | 8 or 9 | |

11 | 7 and 10 | |

12 | 3 and 11 | |

13 | limit 12 to yr = "2020 -Current" |

Searches for ongoing and unpublished trials

ClinicalTrials.gov

31 Studies found for: psychometric | Intellectual Disability OR mental health | Child (birth-17)

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)

https://apps.who.int/trialsearch/

intellect* OR mental*AND psyhometric* propertie* limited clinical trials in children

Appendix III Supplementary material: Excluded studies with exclusion reasons

Abdelghani, E. A., Apollonsky, N., Bernstein, B., & Tarazi, R. (2017). Steady-state cognitive function and pain severity in youth with sickle cell disease. Blood. Conference: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, ASH, 130(Supplement 1). Exclusion reason: Wrong patient population

Abozeid, M., Hamouda, M., Bahry, H., Elmadny, A., Alakbawy, A., & Ismail, A. (2011). Psychiatric morbidity among a sample of orphanage children in Cairo. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1), S166-S167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-011-0181-5. Exclusion reason: Conference Abstract

Accordino, R. E., Kidd, C., Politte, L. C., Henry, C. A., & McDougle, C. J. (2016). Psychopharmacological interventions in autism spectrum disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 17(7), 937-952. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2016.1154536. Exclusion reason: Review