Abstract

Self, peer and teacher reports of social relationships were examined for 60 high-functioning children with ASD. Compared to a matched sample of typical children in the same classroom, children with ASD were more often on the periphery of their social networks, reported poorer quality friendships and had fewer reciprocal friendships. On the playground, children with ASD were mostly unengaged but playground engagement was not associated with peer, self, or teacher reports of social behavior. Twenty percent of children with ASD had a reciprocated friendship and also high social network status. Thus, while the majority of high functioning children with ASD struggle with peer relationships in general education classrooms, a small percentage of them appear to have social success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the well-documented peer difficulties of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), parents and professionals increasingly prefer inclusion of their children in general education classrooms (Kasari et al. 1999). The rationale is that placement of children with ASD in general educational settings increases the involvement of these children in the mainstream, through the behavioral modeling of typical peers, and others’ acceptance and appreciation of people with differences (Guralnick 1990; Villa et al. 1995). Current research suggests that there may be both social benefit and risk for children with ASD in inclusive settings.

Access to typical child models has been suggested as one benefit to social outcomes for children with ASD. For example, Sigman and Ruskin (1999) found that children with ASD were more socially engaged at school if they had access to typical children on the playground. Similarly, Bauminger et al. (2003) found that high functioning children with ASD were more likely to engage with a typical peer on the playground than with children with special needs. Some parents report their child’s inclusive experience as being characterized by peer acceptance, and being able to form meaningful friendships with their non-disabled classmates (Ryndak et al. 1995; Staub et al. 1994). Mainstreamed classrooms may offer an ideal context to use typical peers as social models, encouraging the maintenance and generalization of skills often not achieved by interventions that use an adult interventionist (Carr and Darcy 1990; Roeyers 1996; Shearer et al. 1996).

However, other studies demonstrate that inclusion may be insufficient to truly integrate children with ASD into the social networks of their typical peers (Burack et al. 1997), and may even pose social risks (MacMillan et al. 1996; Ochs et al. 2001; Sale and Carey 1995). High-functioning students with ASD may be at even greater risk for peer rejection than more impaired students with ASD. Students with severe disabilities may be more accepted in classrooms of mostly typical students because they readily stand out. Different expectations can lead typical peers to play a functional, protective role toward them instead of leading to rejection. On the other hand, students with mild disabilities receive little acceptance regardless of classroom composition. Yet both groups are more stigmatized and less accepted than typical students (Cook and Semmel 1999).

Inclusive classrooms may also be over-stimulating and lack specified staff and resources that students with ASD need, causing them to grow dependent on adults in the classroom (Mesibov and Shea 1996). From interviews with adolescents with ASD, it appears that support staff (often in the form of a paraprofessional aide) may mark children as being different, hindering rather than facilitating peer relationships (Humphrey and Lewis 2008). Researchers observing kindergarten and school aged children note that adults assigned to children with ASD are often unsure of what to do on playgrounds and interfere, blocking interactions between children and their peers, resulting in more isolation from peers while increasing the child with ASD’s interactions with adults (Anderson et al. 2004). Inclusion and the practices implemented to facilitate inclusion (e.g., assignment of paraprofessionals to the child with ASD) may not always promote social success of children with ASD.

Children spend the majority of their day at school, but studies have rarely examined the friendships and peer interactions of children with ASD within this context. Rather, most studies ask children or parents to identify friendships without gathering corresponding reciprocity data. As Bauminger and Kasari (2000) note, all of the children in their sample of high functioning children with autism identified a friend. Most children were identified from their school setting; however, several children identified friends that mothers later indicated was the child’s tutor, stepdad, or other unusual choice. Without data from the nominated friend of the child with ASD, we could not judge reciprocity of friendships. In a later study of second and third grade children, we found that approximately one-third of nominated friends reciprocated the friendship of children with ASD at school compared to sixty percent for typical children from the same class (Chamberlain et al. 2007). Thus, reciprocity at school appears to be lower for children with ASD.

While multiple informants are important in determining the social inclusion of children with ASD at school, reporters do not always agree on the degree to which children are socially included. In particular, children with ASD experience misperception of their social involvement at school; they may see themselves as more or less socially involved than their peers or parents report. For example, in one study we found that children with ASD saw themselves as more connected than their peers saw them. Children with ASD nominated many more children as friends at school than peers nominated them (Chamberlain et al. 2007). In another study, children identified fewer friends from any context or setting than their mothers identified for them (Bauminger and Kasari 2000). In this latter study, we did not obtain peer reports so that it was unclear if mothers over-identified or children under-identified their friends. Determining inclusion success appears different depending on the reporter (e.g. peer, child with ASD, parent, teacher) and the circumstances (e.g., observations of actual behavior on playgrounds or survey).

One limitation to our current knowledge of children’s experiences at school is that most studies describe the experiences of only a few children and are limited in the number of measures and reporters that they include. Thus, studies may obtain the child’s report of relationships, and/or their teacher’s or parent’s report, but rarely reports from peers and/or observations of spontaneously occurring peer interactions. In our previous reports of classroom peer nominations, both peers and children with ASD agreed that children with ASD were more often peripheral in their classroom social networks (Chamberlain et al. 2007; Rotheram-Fuller et al. in press). Children with ASD also reported lower quality friendships (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Chamberlain et al. 2007), and their difficulties with their peer social networks were greater at the older grades than the younger grades (Rotheram-Fuller et al. in press). However, these studies did not include actual observations of peer relationships, nor did they include impressions from teachers. Teachers and independent observers of children’s social interactions on the playgrounds offer important additional information on the social inclusion of children with ASD.

It is expected that the peer social network nominations of children should be in line with observations of children on their school playgrounds. Thus, peer reports of children with ASD as peripheral to their classroom social networks should predict that they would be largely unengaged on their school playgrounds. Indeed, studies that have observed children with ASD on playgrounds suggest that they are often unengaged with peers; they make fewer attempts to interact with other children, and are less responsive to other’s bids for social interaction (Sigman and Ruskin 1999). One study found that just four behaviors discriminated over 90% of children with ASD on the playground from other children. These behaviors included poor social engagement with peers, lack of respect for personal space, isolation, and inappropriate behavior (Ingram et al. 2007). The consistent finding that children with ASD are isolated or unengaged on the playground may be due to several possibilities, including that children distance themselves from interactions with others (perhaps wanting to be alone) or that they are unengaged due to their own or others’ actions on the playground. At this point, we do not know how the children themselves (both peers and the child with ASD) and their teachers view their relationships, and how these relationships may play out on the school playground. To date, researchers have not connected all of these measures together in the same study.

The goal of the current study was to connect self and other perceptions to actual observations of children on their playgrounds, and to teacher reports of social interactions at school. While we recognize that children can have friendships in many different contexts, they spend the greatest amount of time at school, and it is the context in which social relationships can have added benefit to both social and academic development. Moreover, for children with ASD, school is the context in which they can feel loneliness and isolation (Bauminger and Kasari 2000). We expected that children with ASD would receive fewer reciprocated friendship nominations, report poorer quality friendships, and be viewed by their peers as more peripheral in their classroom social networks (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Chamberlain et al. 2007; Rotheram-Fuller et al. in press). In this study, however, a primary goal was to examine the association between independent observations of children on the school playground with teacher, peer and self reports of peer relationships. We hypothesized that children who were more peripheral in their social networks, would be less engaged on the playground, have fewer friendships, and receive poorer teacher reports of social skills.

Because children with ASD in this study ranged from first to fifth grade, we were also interested in grade related differences in our measures. In a previously completed study involving 79 children with ASD in kindergarten through fifth grade, grade related changes were found in children’s social networks (Rotheram-Fuller et al. in press). Sixty of these children are participants in the current study and received the additional measures that are the focus of this study (including measures of friendship quality, teacher report of social relationships, and independent playground observations). Thus, we can begin to examine grade-related differences in the connections between self and other reports and actual behaviors of children with ASD in inclusive classrooms.

Method

Participants

A total of 243 children were prescreened for participation in this study and 83 families signed consent from August 2003 to September 2007. The majority of families who did not meet the prescreening criteria lived outside of our catchment area (within 90 min of the University). Children were included in this study if they had a diagnosis of ASD from a licensed psychologist, if they met criteria for ASD on the ADI-R and ADOS, were fully included in a regular education classroom for at least 80% of the school day, were between the ages of 6–11 years old and in grades 1–5, and had an IQ of 65 or higher. Children were excluded from this study if they had additional diagnoses. Of the 83 children with ASD who signed consent, 23 did not participate for a variety of reasons (nine schools refused participation; six parents withdrew before the assessments; six children did not meet the IQ criteria; two children did not meet criteria for ASD). All peers from each participating child with ASD’s classroom were then invited to participate in the study. Both parental consent and child assent were obtained from all participating peers.

A total of 60 children with ASD and 815 typically developing children participated in this study. Research clinicians not associated with the study independently evaluated all children with ASD. Overall, 44 children received an autism diagnosis, and 16 children received an Asperger diagnosis. Participants were recruited from 56 classrooms in 30 different schools across the greater Los Angeles area (53% of the schools were Title I schools). Of the children with ASD, 15 children were in first grade, 18 children in second grade, eight children in third grade, 11 children in fourth grade, and eight children in fifth grade. Children with ASD were from diverse ethnic backgrounds (46.7% Caucasian, 5% African American, 21.7% Latino, 16.7% Asian, and 10% Other) and were predominantly male (90%). All were fully included in regular education classrooms for 80% or more of the school day and were an average of 8.14 ± 1.56 years old, with an average IQ of 90.97 ± 16.33. One family refused the IQ test but previous reports of IQ were in the normal range. Sixty percent of the children with ASD were assigned a 1:1 aide in the classroom and on the playground. Children assigned an aide had significantly lower IQs than children without an aide, t(1, 57) = 3.07, p = .003. Average IQ of children with NO AIDE (N = 24) was 98.33 (SD = 19.23) and of children WITH AIDE (N = 35) was 85.91 (SD = 11.86).

To allow for direct comparisons to the children with ASD, a subsample of typical children was randomly selected from each child’s classroom that matched the children with ASD on gender, age, grade and classroom. Typically developing children were an average of 7.86 ± 1.43 years old. Further demographic data were not available for the matched peers.

Measures

Friendship Qualities Scale(FQS; Bukowski et al. 1994). The FQS is a 23-item questionnaire that examined five features of friendship quality: (a) companionship (amount of voluntary time spent together), (b) help (encompassing both aid and protection from victimization), (c) security (including trust and the idea that the relationship will transcend specific problems), (d) closeness (consisting of both the child’s feelings toward the partner and his or her perceptions of the partner’s feelings), and (e) conflict (disagreements in the friendship relation). Children rated how true a sentence description was of their best friendship using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always). This measure has been used in previous studies of children with autism and their peers (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Bauminger et al. 2004; Chamberlain et al. 2007).

Playground Observation of Peer Engagement (POPE) (Kasari et al. 2005). Designed for this study, the POPE is a time-interval behavior coding system. Researchers recorded children’s engagement with peers on the playground, and frequency of initiations and responses (see Table 1 for description). Independent observers watched the target child on the playground for 40 consecutive seconds and then coded for 20 s for at least ten minutes during the recess or lunch play period on two separate occasions within 1 week. The observers noted the child’s engagement with peers on the playground (solitary, proximity, onlooking, parallel, parallel aware, involved in games with rules and joint engaged with peers) in each interval. Playground engagement states were summed for a total proportion of intervals in each engagement state.

Coders also noted two types of children’s initiations toward other children. First, observers coded for successful initiations to peers where the child directs communication to a peer/peers (e.g. offers toy, greets, asks to play game, comments, states facts, etc.) and the peer responds with a nonverbal gesture (e.g. head nod/shake, follows the child, laughs, etc.) or verbal language. Second, observers rated children’s failed initiation attempts where the target child directs communication to a peer/peers and the peer does not respond or ignores the child. Coders also noted two types of child responses to others including the children’s appropriate responses to a peer’s initiation (e.g. child says yes when a peer asks him/her to play) as well as the child’s missed responses to a peer’s initiation (e.g. a peer asks him/her to play and the child does not respond). Playground observations included a comment section where the observer qualitatively documented whether or not the child had a 1:1 aide and the type of activity he/she engaged in with the child on the yard.

Playground engagement states were summed into total interval counts that yielded a total percentage of intervals in each engagement state, and frequency of social behaviors (e.g., initiating to others and responding to peers’ social overtures) within each observed interval. To correct for varying intervals per observation, the number of intervals children spent in each engagement state was divided by the total number of observed intervals for that observation period.

Prior to beginning the study, all observers were trained and considered reliable with percent agreement >.80. Observers then overlapped on 15% of all observations distributed over the course of the study to assess coder reliability and drift. When conducting reliability two observers overlapped on sessions and began their stopwatches at the same time, but coded independently. Reliability was estimated with Kappa statistic, and averaged .91 (range .83–.96).

Teacher Perception Measure. The Teacher Perception Measure was a 26 item questionnaire completed by teachers and adapted from the Personal Maturity Scale (Alexander and Entwisle 1988), the Child Behavior Checklist for Preschool-Aged Children, Teacher Report (Achenbach et al. 1987) and the Behavior Problems Index (Zill 1990) by the Early Head Start FACES program. The adapted measure used a 3-point Likert scale to rate 12 items regarding teachers’ perceptions of students’ social skills (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = very often) and 14 items regarding the teacher’s perceptions of children’s classroom conduct (1 = not true, 2 = somewhat or sometimes true, 3 = very true or often true). The social skills domain described the child’s strengths, such as adaptability to the school classroom and environment, quality of interactions with peers, and popularity or likeability among peers. The classroom conduct domain described problems, such as disruptive, impulsive, withdrawn, and depressive behaviors; problems in school-related skills and motivation; and difficulty following directions. The Early Head Start FACES program reported good internal consistency for this measure, ranging from .72 to .88.

Social Networks and Friendship Survey. Children were asked to identify who they like to hang out with in their classroom. From this list the children generated, they were instructed to circle their top 3 friends, and place a star next to their best friend from among the 3 names that were circled. They were also asked to list any children they did not like to hang out with (rejects). Next, participating students were asked: “Are there kids in your class who like to hang out together? Who are they?” Children listed the names of other children who hung around together in groups; they were reminded to include themselves in groups as well as to remember to include students of both genders. Children circled the groups of children who they identified as hanging out together. This method has been used in various studies from early childhood through adolescence to assess the social structure of individual classrooms for both typical and atypical populations (Cairns and Cairns 1994; Farmer and Farmer 1996; Chamberlain et al. 2007; Locke et al. 2010).

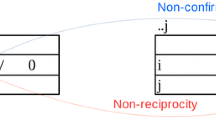

Coding Indegrees, Outdegrees, Connects, and Rejects. These variables were coded from the Friendship Survey. Indegrees were coded as the total number of received friendship nominations - the number of classmates that listed the child as “someone they like to hang out with,” whereas outdegrees were coded as the total number of outward friendship nominations by the child—the number of classmates the child listed as “someone they like to hang out with.” Children’s connects score was calculated as the total number of children that were significantly linked on the social network map. Each line segment from the social network map indicated a significant connection to a classmate from that child (See Fig. 1). Lastly, rejects were coded as the total number of times children were identified as someone other children “did not like to hang out with”.

Sample social network map where the target child is an isolate. All other lines stemming from children’s ID numbers indicate significant classroom connections. Numbers in parenthesis next to the ID number represent children’s individual scores. Numbers within the cluster are children’s group scores (*** denotes the target child with autism)

Coding Friendship Reciprocity. Children were considered to have reciprocal friendships if they selected each other as their top 3 or best friends within the classroom. A conservative method of determining reciprocal friendships was used, such that when one of the students nominated was absent, or did not complete the measure, it was coded as missing data instead of a non-reciprocal friendship.

Coding Social Network Centrality (Cairns and Cairns 1994). Following Cairns and Cairns (1994), social network analyses were conducted in order to obtain each child’s social network centrality score. Social network centrality refers to the prominence of an individual in the overall classroom social structure. Three related scores were calculated in order to determine a student’s level of involvement in the classroom’s social networks: (1) the student’s “individual centrality,” (2) the “cluster centrality” of each social group within the class, and (3) the student’s combined “social network centrality” score. Using methods developed by Cairns and Cairns (1994), the first two types of centrality were used to determine the third (Cairns et al. 1990; Farmer and Farmer 1996). Based on categorizations by Farmer and Farmer (1996), four levels of social network centrality were possible. These four levels of involvement (i.e. isolated, peripheral, secondary, and nuclear) in the classroom’s social structure were coded from 0 to 3, to provide a system for describing how well the child with ASD was integrated into the informal peer networks. Children that were considered ‘isolated’ received a score of 0 for their social network centrality and were not considered part of any cluster of children within their classroom. Children that were considered ‘peripheral’ received a score of 1 for their social network centrality and were considered on the outskirts of their classroom’s social structure. These children may have a few connections to other children within the classroom but are not salient members of their classroom’s social network. Children that were considered ‘secondary’ received a score of 2 on their social network centrality and were considered well connected members of their classroom social structure. Lastly, children that were considered ‘nuclear’ received a score of 3 on their social network centrality and were considered ‘popular’ and central members of their classroom social structure. These children were individually salient (nominated frequently) and were also significantly connected to other children who were very salient on an individual level. Children’s total social network centrality status could only be as high as their lowest centrality score derived from their individual or cluster centrality score.

Procedures

Once families completed the informed consent process, they were assessed by independent evaluators to validate the clinical diagnosis of ASD via the ADI-R (Lord et al. 1994) and ADOS (Lord et al. 2000) evaluations. Independent evaluators also administered the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III; Weschler 1991) to obtain a developmental quotient. Children with an IQ of 65 or higher and who had a diagnosis of ASD were included in the study.

Upon entry into the study, research personnel contacted the target child’s school and obtained a letter of school participation for the study. Once school approval was obtained, consent forms were distributed to all children in the class. Children were informed that their classroom was selected to participate in a research study examining children’s friendships and social skills. Children, who returned informed consent from their parents, as well as offered assent to join the study, completed the social network measures (including brief demographic information) and the Friendship Qualities Scale. To ensure understanding of the measures, research personnel provided verbal instructions on how to complete the instruments and individually assisted children who had difficulty reading and/or writing and/or were in the youngest grades. Children in the older grades independently completed the measures after instructions were given. In addition, teachers were asked to complete the Teacher Perceptions Scale for the child with ASD during this visit. Within the same week of distributing classroom measures, research personnel gathered behavioral observations on the playground during two separate recess periods.

Results

Analyses below are based on 120 children, 60 children with ASD and a paired sample of 60 typically developing peers (children matched on age and gender from the same classroom). There were no differences on outcome measures between children diagnosed with Asperger syndrome (n = 16) and autism (n = 44); therefore, the following analyses included all 60 children with ASD. We first report descriptive data for the groups on measures of peer nomination and friendship ratings: social network centrality, friendship nominations (indegrees, outdegrees, connections, rejects, reciprocity of best and top 3 friends), and friendship quality ratings. In each case, we tested for group and grade-related differences. Next we report the descriptive data for the playground observations of children with ASD, and finally report individual differences in measures for the children with ASD.

Descriptive Data: Self-and Other Perceptions of Social Connections for Children With and Without ASD

Social Network Centrality. For the group of children with ASD, 8 children were isolated, 25 had peripheral status, 22 had secondary status, and five had nuclear social status. In contrast, none of the typically developing children were isolated, six had peripheral status, 35 had secondary status and 19 had nuclear status. See Fig. 2.

Consistent with our earlier studies, an ANOVA indicated that there was a significant group difference for social network centrality, F(1, 116) = 38.57, p < .0001. Children with ASD had significantly poorer social network centrality (1.38 ± .09) compared to typically developing matched peers (2.20 ± .09). There was a significant main effect of grade level, F(1, 116) = 4.87, p = .03 where children in the older grades (3rd–5th) had lower social network centrality (1.65 ± .10) than children in the younger grades (1st–2nd; 1.93 ± .09). There was no significant interaction between grade and diagnostic group.

Friendships, Connections, and Rejections. A MANOVA with grade and diagnostic group as independent variables was used to compare the number of children’s friendships, connections, and rejections within his/her classroom between typically developing children and children with ASD. Of the 120 children, 114 children were used in this analysis because three children with ASD did not complete the rejections portion of the friendship survey, as it was added after the study began; thus, these students (and their matched peers) were excluded from this analysis.

The multivariate result was significant for group, Wilks Lambda = .79, F(1, 106) = 7.13, p ≤ .001, indicating a difference in friendships between children with ASD and their typically developing peers. The univariate F tests showed a significant difference between children with ASD and their matched peers for the number of friends they nominated within the classroom (outdegrees; F(1, 106) = 8.57, p = .004), the number of received friendship nominations by other children (indegrees; F(1, 106) = 18.84, p ≤ .001), and the number of classroom connections (connects; F(1, 106) = 14.61, p ≤ .001). Children with ASD nominated fewer peers as friends (3.76 ± .34), were nominated fewer times as a friend by peers (1.48 ± .24) and had fewer overall classroom connections (i.e., smaller social networks; 2.76 ± .33) than their typically developing matched peers (5.17 ± .34; 2.92 ± .24; 4.54 ± .33, respectively). Children with ASD did not differ from typically developing children in their percentage of connections to peers by gender. Boys were more often connected to boys and girls to girls for both groups. Lastly, when examining children’s number of rejections, there was no significant difference in the number of rejection nominations received by children with ASD relative to their matched peers. There was no main effect of grade or a group by grade interaction for these outcomes (see Fig. 3).

Reciprocal Friendships. Both reciprocated top 3 friends and best friendships were examined using an ANOVA. For their top 3 friends, the overall model was significant, F(3, 99) = 13.12, p < .0001 with a significant main effect for group, F(1, 99) = 39.22, p < .0001.The percentage of children’s reciprocal friendships with their nominated top three best friends was significantly lower for children with ASD (17.91% ± 5.32) in comparison to their typically developing matched peers (63.91% ± 5.07). There was no main effect of grade or a group by grade interaction.

The overall model was significant for reciprocal best friends, F(3,61) = 3.94, p = .0123, with a significant main effect of group, F(1, 61) = 10.82, p = .0017. Children with ASD had fewer reciprocal best friends than did typical children, (11.33% ± 8.4 compared to 44.97% ± 7.08), respectively. There was no main effect of grade or a group by grade interaction. See Fig. 4.

In addition, there was no difference between children with ASD and typically developing children in whether they selected a same-sex best friend (χ2(1, N = 116) = 3.42, p = .09). The majority of both groups chose same sex best friends, 56 out of 60 typically developing children and 46 out of 56 children with ASD. Four children with ASD did not list any peer as a friend.

Friendship Quality Scale. A MANOVA with grade and diagnostic group as independent variables was used to compare the five domains of child-rated friendship quality (i.e. companionship, help, security, conflict, and closeness) between typically developing children and children with ASD. Of the 120 children in the matched sample, 116 children were used in this analysis. Four children with ASD did not list a best friend and therefore did not complete the FQS; therefore, they were excluded from the analysis.

The multivariate result was significant for group, Wilk’s Lambda = .84, F(1, 108) = 4.13, p = .002, indicating a difference in friendship quality between children with ASD and their typically developing peers. The univariate F tests showed there was a significant difference between children with ASD and their matched peers for closeness, F(1, 108) = 17.87, p ≤ .001, security, F(1, 108) = 4.45, p = .04, helpfulness F(1, 108) = 15.00, p ≤ .001, and companionship, F(1, 108) = 8.60, p = .004, in that children with ASD reported poorer friendship quality in all four domains (see Table 2). Children’s perceptions of conflict with respect to their best friendships were not significantly different between the two groups. There was no main effect of grade or a group by grade interaction for any domain of friendship quality (see Fig. 5).

Within the Autism Group Analyses: Playground Observations of Children with ASD

On the playground, children with ASD were engaged with their peers for just over a third of the observed intervals on the playground (38.6% of the total intervals). Children engaged in structured games with rules for approximately 20% of the observed intervals, and 18.6% of the observed intervals in joint engaged activities, such as having a conversation. For the remaining percentage of observed intervals, children were either solitary/unengaged (33.4%), or in lower levels of engagement: parallel play (6%); in proximity to other children (8%); parallel aware (engaging in similar activities with mutual social awareness; 7%); and onlooking (watching another group of children engaged in a game or activity; 7%). The rate of initiations to peers was, on average, once every 3 intervals (mean of 5.13 initiations during 15.79 observed playground intervals). Peers responded to the child with ASD in approximately 66% of the opportunities observed. Peers also initiated to the child with ASD an average of once every four intervals and the child with ASD responded to the peer in 75% of the opportunities observed.

Children with ASD who had a higher percentage of intervals observed in joint engagement and games on the playground also initiated to other children more often on the playground, r = .45, p ≤ .001, and responded more to peers’ initiations, r = .57, p ≤ .001. In addition, children with ASD who were more engaged on the playground were significantly less likely to have a 1:1 aide, r = −.27, p = .04.

Qualitative notes from observations: In order to determine if children with an aide were more likely to be interacting with their aide rather than with other children, we examined the qualitative comments made by the independent coders for each observation. During the playground observations the observer noted if the child was interacting with their aide or with peers. Two raters further coded the qualitative comments about what the child was doing during recess. These raters agreed 100% on the statements about the child’s behavior and the role of the aide. Categories included child unengaged but peers nearby, completely unengaged with peers or adults, wandering or unfocused, engaged with the aide or engaged with peers. Half of the children assigned an aide were observed as unengaged on the playground (18/36 children or 50%), 12 were wandering or unfocused and 6 were unengaged with peers but other children were nearby (e.g., eating nearby, or digging in the sand nearby). Another 14% (5 children) were observed interacting with their aide only. The rest of the sample (13/36 or 36%) was observed interacting with peers or engaged in games. Children with an aide were most often unengaged on the playground, neither interacting with peers or with the aide.

Connections Between Playground Observations, Peer, Self and Teacher Reports for Children with ASD

Correlations were run to determine if playground variables (engagement/games, unengaged/solitary, initiations, responses) were associated with peer nominations (indegrees, outdegrees, rejects, connects), social network centrality (SNC), and friendship quality for the children with ASD. None of the correlations reached significance.

We then explored whether children with ASD who were more engaged on the playground differed by teacher report of social skills. Using chi square statistics, we found that teachers rated children who were more engaged on the playground as having higher social skills, although the association was only marginally significant, χ2(1, N = 56) = 3.78, p = 06.

Next we tested whether the children who had a reciprocal friendship were more engaged on the playground, and whether peers rated these children differentially. Twenty percent of the children with ASD (N = 12) had at least one reciprocal friendship. These children had significantly higher social network centrality scores (2.17 ± .20) as compared to children with ASD who did not have a reciprocal friendship (1.24 ± .11; χ2(1, N = 49) = 11.59, p = .001). Having a reciprocal friendship, however, was not associated with being more engaged on the playground (χ2(1, N = 49) = .67, p = 1.00).

Discussion

Children with ASD in general education classrooms are most often on the periphery of their classroom social networks. Their social networks are smaller than typical classmates, the friendships they identify are less often reciprocated, and the quality of their friendships is poorer. These data for children in first through fifth grade are consistent with a previous report on second and third graders (Chamberlain et al. 2007), and further document the significant social impairment that these children experience at school. However, the current data go beyond our earlier report in three main ways.

First, our previous study was limited to a small number of high functioning children with ASD (N = 17) and a more cohesive set of classrooms in which schools participating tended to have more services available, and may have been motivated to participate because ‘things were going well’ (Chamberlain et al. 2007). We found that none of the children in our previous study were isolated, but they were more often peripheral in their social networks. Moreover, a gender effect was noted, with mostly boys with ASD connected to social networks of girls (Chamberlain et al. 2007). In the current study, a larger sample of 60 children with ASD was recruited from a diverse set of classrooms (half were from Title I schools). We found again that children with ASD were mostly peripheral in their classroom social networks, but there were also isolated children (approximately 13% of the sample). The gender effect we found previously was not noted in the current study. Thus, consistent with typical peer social interactions, boys were connected to boys and girls to girls, and these findings were consistent for younger and older children with ASD (Fein 1981; Pellegrini et al. 2007).

Reciprocity of friendships was particularly low for this sample of children, 18% compared to 64% of their typical classmates, and also lower than a previous study of 34% of second and third graders with ASD (Chamberlain et al. 2007). Friendships of children with ASD may be better characterized as unilateral rather than reciprocal. Because friendships in the school context are important given the amount of time children spend in school, and the importance of friends in promoting social and academic outcomes (Ladd 1999), it will be important for future studies to determine whether unilateral friendships satisfy similar needs as reciprocal friendships for children with ASD (Freeman and Kasari 1998). Additionally, friendships outside of the school setting may provide a protective function to children while in school, although studies have not examined this possibility.

Second, there is some data suggesting that children with ASD have poorer relationships at older ages (Orsmond et al. 2004; Rotheram-Fuller et al. in press). While we found group effects in nearly all measures with children with ASD doing less well compared to their typically developing classmates, we found few grade differences and no grade by group differences. There was only a grade effect for social network centrality with all children (children with and without ASD) having lower social network centrality at the older grades. Relationships in general become more selective (and perhaps more challenging to maintain) as children get older (Howlin et al. 2004; Orsmond et al. 2004). This phenomenon appears the same for children with ASD as it is for typically developing children.

Third, prior studies have not linked peer and child self reports to systematic and independent playground observations and teacher reports. Thus, the current study extends our previous findings by examining the links between peer, self, and teacher reports, and observations of children in their natural environment at school. One might expect that children whose peers see them as more socially connected to other children in the class would also be more engaged on the playground. Yet, contrary to our expectations, there was little association between playground engagement and peer nominations of social connections. Regardless of social status in the classroom, children with ASD were just as likely to be unengaged on the playground if they were rated as popular or isolated. Moreover, even with a reciprocal friendship, children with ASD were no more engaged on the playground than were children with ASD who did not have a reciprocal friendship. Although a limitation of the study is the lack of comparable playground data for the typical peers, these data do provide insight into the potential problems children with ASD experience on the playground, despite having some important connections to their peers.

There are several reasons why the playground may be a difficult environment for children with ASD. One is that in contrast to the structure and expectations of the classroom in which children may be able to connect with peers, the playground is often chaotic and crowded. Even with a reciprocal friend, children with ASD may be unable to access the playground culture at their school. While adults may be present on the yard, they are often more concerned with safety than with facilitation of engagement between peers (Anderson et al. 2004). Indeed, adults often believe recess is a time away from adult intrusions, and that most children understand how to play with each other (Giangreco and Broer 2005). Yet, for children with ASD, playing and engaging with others is likely the most difficult time of their day. It seems likely that the playground is a good setting for social skills interventions for children with autism. As a result, one of the most common interventions for children with ASD is to assign support staff, often in the form of a 1:1 aide (Anderson et al. 2004). In this study, over half of the children were assigned an aide. Children with aides were less likely to be engaged with peers on the playground, and qualitative data indicated they were mostly unengaged from their peers and also not engaged with their aides. These data suggest that aides were unable to facilitate more peer engagement of children on the playground. Future studies should carefully consider the role of the paraprofessional assigned to children with ASD. Several studies now highlight the critical need for aide training, so that aides learn how to best facilitate interactions between children, and take care not to stigmatize and otherwise isolate the child with ASD (Anderson et al. 2004; Humphrey and Lewis 2008; Brown et al. 2001).

Finally, the situation for children with ASD in inclusive classrooms was not completely bleak. Children with ASD did not differ from typical children in the number of rejection nominations they received from their peers. This finding, along with the relatively low levels of isolated children nominated on the social networks measure, suggests that children with ASD have more potential for fitting into their typical school classrooms than other data-based and anecdotal reports would suggest (Church et al. 2000; Humphrey and Lewis 2008). Rather than active rejection, children with ASD may fall into the class of neglected children, often overlooked as potential playmates by other children in the class (Asher and Wheeler 1985).

While our informant measures (peer, teacher and child with ASD) did not link to our playground observations, observations of children on the playground yielded consistent data for children’s level of engagement with initiations and responses to peers. When children were engaged in games or conversations, there were more initiations and responses to and from peers. Thus, increasing engagement with children on the playground is an important target of intervention that may move children from the periphery of groups to more central roles within the group. More engagement may lead to increased opportunities to hone social skills, both in navigating positive interactions, and in negotiating conflicts. Better engagement on the playground also appears associated with more get-togethers of children outside of school (Frankel et al. 2010). Therefore, a goal for future studies will be to more closely examine the effects of increased engagement on children’s social developmental outcomes.

The current study goes beyond earlier studies by combining data from multiple sources and by using multiple methods on a large sample of children with autism. Still, there remain a number of limitations that should be considered in interpreting the findings, and in designing future studies. First, this study highlights some of the difficulties in working within school settings that involve as few as 1 or 2 classrooms per school that contain a child with autism. Obtaining enough data on each child becomes a challenge when sample sizes are fairly large (n = 60) and classrooms are many, as in the present report. Beyond the relatively small corpus of observational data per participant (two recess periods in one week contributing less than 30 min of observational data), other limitations include the lack of data on the typically developing matched peers. We were unable to collect playground observational data and other background information on the typical classmates. This may be avoided in future studies if the typical classmates are consented and matched from the beginning of the study. Our approach was to utilize all of the children in the class to obtain the social network centrality measure and then to randomly select one child who could match the child with autism on meaningful variables of age, gender and same classroom. We were not able to verify ethnicity, or other background variables on the children, and it is possible that these variables may have influenced the results despite the fact that children were in the same class, same school and same neighborhood. Future studies will need to consider these factors in making comparisons to children with autism in general education classrooms.

In summary, this study provides a unique look into the school social experiences of a diverse group of high- functioning children with ASD. Information was gathered from multiple sources, including the child with ASD, his or her peers, and teacher, as well as independent observations of interactions on the child’s playground. While measures converged from multiple informants (teachers, peers and child with ASD) on the level of connection between the child and his or her peers and the reciprocity of their friendships, there was little association to observations made independently on the playground. Thus, these data yield a complicated picture of the social lives of children with ASD suggesting that success with peers may be greater if the supports are in place to engage children with their peers on the school playground.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Edelbrook, C., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Empirically based assessment of the behavioral/emotional problems of 2- and 3-year old children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An official publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 15, 629–650.

Alexander, K. L., & Entwisle, D. R. (1988). Achievement in the first 2 years of school: Patterns and processes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 53, i-157.

Anderson, A., Moore, D. W., Godfrey, R., & Fletcher-Flinn, C. M. (2004). Social skills assessment of children with autism in free-play situations. Autism, 8, 369–385.

Asher, S., & Wheeler, V. A. (1985). Children’s loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 500–505.

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71, 447–456.

Bauminger, N., Shulman, C., & Agam, G. (2003). Peer interaction and loneliness in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(5), 489–507.

Bauminger, N., Shulman, C., & Agam, G. (2004). The link between perceptions of self and of social relationships in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 16(2), 193–214.

Brown, W. H., Odom, S. L. & Conroy, M. A. (2001). An intervention hierarchy for prompting young children’s peer interactions in natural environments. Topics in Early Special Education, 21(3), 162–175.

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. Special Issue: Children’s Friendships, 11(3), 471–484.

Burack, J. A., Root, R., & Zigler, E. (1997). Inclusive education for students with autism: Reviewing ideological, empirical and community considerations. In D. J. Cohen, F. R. Volkmar, D. J. Cohen, & F. R. Volkmar (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (pp. 799–807). New York: Wiley.

Cairns, R., & Cairns, B. (1994). Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cairns, R. B., Gariépy, J.-L., & Kindermann, T. A. (1990). Identifying social clusters in natural settings. Unpublished manuscript. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina and Chapel Hill.

Carr, E. G., & Darcy, M. (1990). Setting generality of peer modeling in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(1), 45–59.

Chamberlain, B., Kasari, C., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2007). Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(2), 230–242.

Church, C., Alisanski, S., & Amanullah, S. (2000). The social, behavioral, and academic experiences of children with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(1), 12–20.

Cook, B. G., & Semmel, M. I. (1999). Peer acceptance of included students with disabilities as a function of severity of disability and classroom composition. The Journal of Special Education, 33, 50–61.

Farmer, T. W., & Farmer, E. M. Z. (1996). Social relationships of students with exceptionalities in mainstream classrooms: Social networks and homophily. Exceptional Children, 62(5), 431–450.

Fein, G. G. (1981). Pretend play in childhood: An integrative review. Child Development, 52(4), 1095–1118.

Frankel, F., Gorospe, C. M., Chang, Y., & Sugar, C. A. (2010). Mothers reports of play dates and observation of school playground behavior of children having high-functioning autism spectrum disorders (submitted).

Freeman, S., & Kasari, C. (1998). Friendships in children with developmental disabilities. Early Education and Development, 9, 341–355.

Giangreco, M., & Broer, S. (2005). Questionable utilization of paraprofessionals in inclusive schools: Are we addressing symptoms or causes? Focus on Autism and other Developmental Disabilities, 20, 10–25.

Guralnick, M. J. (1990). Social competence and early intervention. Journal of Early Intervention, 14, 3–14.

Howlin, P., Goode, S., Hutton, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 212–229.

Humphrey, N., & Lewis, S. (2008). Make me normal: The views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism, 12, 1362–3613.

Ingram, D. H., Mayes, S. D., Troxell, L. B., & Calhoun, S. L. (2007). Assessing children with autism, mental retardation, and typical development using the Playground Observation Checklist. Autism, 11, 311–319.

Kasari, C., Freeman, S. F. N., Bauminger, N., & Alkin, M. C. (1999). Parental perspectives on inclusion: Effects of autism and down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(4), 297–305.

Kasari, C., Rotheram-Fuller, & Locke. J., (2005). The development of the playground observation of peer engagement (POPE) Measure. Unpublished manuscript. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Los Angeles.

Ladd, G. W. (1999). Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 333–359.

Locke, J., Ishijima, E., Kasari, C., & London, N. (2010). Loneliness, friendship quality, and the social networks of adolescents with high-functioning autism in an inclusive school setting. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Jr., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., et al. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule–generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685.

MacMillan, D. L., Gresham, F. M., & Forness, S. R. (1996). Full inclusion: An empirical perspective. Behavioral Disorders, 21(2), 145–159.

Mesibov, G. B., & Shea, V. (1996). Full inclusion and students with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26(3), 337–346.

Ochs, E., Kremer-Sadlik, T., Solomon, O., & Sirota, K. G. (2001). Inclusion as social practice: Views of children with autism. Social Development, 10(3), 399–419.

Orsmond, G. I., Krauss, M. W., & Seltzer, M. M. (2004). Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 245–256.

Pellegrini, A. D., Long, J. D., Roseth, C. J., Bohn, C. M., & Van Ryzin, M. (2007). A short-term longitudinal study of preschoolers’ (Homo sapiens) sex segregation: The role of physical activity, sex, and time. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 121, 282–289.

Roeyers, H. (1996). The influence of nonhandicapped peers on the social interactions of children with a pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26(3), 303–320.

Rotheram-Fuller, E., Kasari, C., Chamberlain, B., & Locke, J. (in press). Grade related changes in the social inclusion of children with autism in general education classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry.

Ryndak, D. L., Downing, J. E., Jacqueline, L. R., & Morrison, A. P. (1995). Parents’ perceptions after inclusion of their children with moderate or severe disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 20(2), 147–157.

Sale, P., & Carey, D. M. (1995). The sociometric status of students with disabilities in a full-inclusion school. Exceptional Children, 62(1), 6–19.

Shearer, D., Kohler, F., Buchan, K., & McCullough, K. (1996). Promoting independent interactions between preschoolers with autism and their nondisabled peers: An analysis of self-monitoring. Early Education and Development, 7, 205–220.

Sigman, M., & Ruskin, E. (1999). Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(1), v-114.

Staub, D., Schwartz, I. S., Gallucci, C., & Peck, C. A. (1994). Four portraits of friendship at an inclusive school. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 19(4), 314–325.

Villa, R., Thousand, J., & Rosenberg, R. (1995). Creating heterogeneous schools: A systems change perspective. In M. Falvey (Ed.), Inclusive and heterogeneous schooling: Assessment, curriculum, and instruction (pp. 1–50). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Weschler, D. (1991). Manual for the Weschler intelligence scale for children (3rd edn ed.). New York: Psychological Corporation.

Zill, N. (1990). The behavior problems index [descriptive material]. Washington, DC: Child Trends.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIMH grant 5-U54-MH-068172 and HRSA grant UA3MC11055. We thank the children, parents, schools and teachers who participated, and the individuals who contributed countless hours of assessments, intervention, and coding, Laudan Jahromi, Lisa Lee, Eric Ishijima, Kelly Goods, Nancy Huynh, Mark Kretzmann, Tracy Guiou and Steve Johnson. We especially appreciate the statistical support of Jeff Wood and Fiona Whalen from the UCLA Semel Institute Statistical Group and to Steven Kapp for feedback on earlier versions of the paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kasari, C., Locke, J., Gulsrud, A. et al. Social Networks and Friendships at School: Comparing Children With and Without ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 41, 533–544 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x