Abstract

This study investigated associations between maternal prenatal smoking and physical aggression (PA), hyperactivity-impulsivity (HI) and co-occurring PA and HI between ages 17 and 42 months in a population sample of children born in Québec (Canada) in 1997/1998 (N=1745). Trajectory model estimation showed three distinct developmental patterns for PA and four for HI. Multinomial regression analyses showed that prenatal smoking significantly predicted children’s likelihood to follow different PA trajectories beyond the effects of other perinatal factors, parental psychopathology, family functioning and parenting, and socio-economic factors. However, prenatal smoking was not a significant predictor of HI in a model with the same control variables. Further multinomial regression analyses showed that, together with gender, presence of siblings and maternal hostile reactive parenting, prenatal smoking independently predicted co-occurring high PA and high HI compared to low levels of both behaviors, to high PA alone, and to high HI alone. These results show that maternal prenatal smoking predicts multiple behavior regulation problems in early childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The literature on maternal prenatal smoking and externalizing behavior problems is clearly separated in two developmental periods. The bulk of the current literature on maternal prenatal smoking and externalizing behavior problems covers either childhood and adolescence or the preschool years. However, the rates of common childhood psychiatric disorders such as conduct disorder (CD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the patterns of comorbidity among them in early childhood are similar to those seen in later childhood (Egger & Angold, 2006). Limitations in current diagnostic criteria for early childhood psychopathology have resulted in a research focus on specific behaviors such as physical aggression (PA) and hyperactivity-impulsivity (HI) rather than clinical disorders in this age group. Both physical aggression and hyperactivity during early childhood appear to be typical precursors of full-blown CD and ADHD during the school years and beyond (Séguin, Nagin, Assaad, & Tremblay, 2004). A substantial number of studies show continuity between early and late childhood externalizing behavior problems (e.g. Campbell, Breaux, Ewing, & Szumowski, 1986; Keenan & Wakschlag, 2000) or have identified consistent developmental trajectories for PA and HI that start as early as age 1 1/2 years (e.g. Côté, Vaillancourt, LeBlanc, Nagin, & Tremblay, 2006; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004; Romano, Tremblay, Farhat, & Côté, 2006; Shaw, Lacourse, & Nagin, 2005).

In reviewing childhood and adolescence studies, maternal prenatal smoking has consistently been associated with CD- and ADHD- symptoms (for reviews, see Linnet et al., 2003; Wakschlag, Pickett, Cook, Benowitz, & Leventhal, 2002). The associations have been observed in clinical samples (e.g. Mick, Biederman, Faraone, Sayer, & Kleinman, 2002; Milberger, Biederman, Faraone, Chen, & Jones, 1996), ‘at-risk’ samples (e.g. Wakschlag & Hans, 2002) and large population-based samples (e.g. Braun, Kahn, Froehlich, Auinger, & Lanphaer, 2006; Kotimaa et al., 2003). Whereas these studies generally controlled for familial psychopathology and numerous environmental risk factors, there are also indications from studies using (large) twin samples that maternal prenatal smoking predicts children’s CD- and ADHD-symptoms beyond the effects of heritable risk (e.g. Button, Thapar, & McGuffin, 2005; Maughan, Taylor, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2004; Silberg et al., 2003; Thapar et al., 2003). Studies showing associations between maternal prenatal smoking and CD-symptoms and delinquency during adolescence and adulthood (Brennan, Grekin, Mortensen, & Mednick, 2002; Fergusson, Woodward, & Horwood, 1998; Räsänen et al., 1999) and studies showing behavior problems in children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy at different time points (e.g. Maughan et al., 2004; Wakschlag & Hans, 2002; Wakschlag, Pickett, Kasza, & Loeber, 2006) suggest long-lasting effects.

Although there are indications that maternal prenatal smoking is more strongly or even exclusively related to CD symptoms (Wakschlag & Hans, 2002; Wakschlag, Leventhal, Pine, Pickett, & Carter, 2006; Wakschlag, Pickett et al., 2006), only few studies tested for specificity of the relations between maternal prenatal smoking and CD- or ADHD-symptoms (Button et al., 2005; Mick et al., 2002; Thapar et al., 2003). This is an important matter considering the high comorbidity of these behavior problems (e.g. Jensen, Martin, & Cantwell, 1997). Mick et al. (2002) found a robust link with ADHD-symptoms after controlling for CD-symptoms in a clinical population. In that study, children aged 6 to 17 years with ADHD and non-ADHD controls were compared after statistical control for CD. In contrast, Thapar et al.’s (2003) and Button et al.’s (2005) population-based twin study using the Greater Manchester Twin Register did not select on either CD- or ADHD-symptoms. Whereas Thapar et al. showed that prenatal maternal smoking predicted a unique proportion of the variance in ADHD-symptoms after control for CD-symptoms in children between 5 and 16 years, Button et al. (2005) tested a more complex model showing unique variance for both CD- and ADHD-symptoms in children 5 to 18 years of age. Although the aforementioned studies used some form of statistical control for the symptoms associated with the ‘other’ disorder, only one study to date examined a relation between prenatal maternal smoking and co-occurring behavior problems (Wakschlag, Pickett et al., 2006). In that study maternal prenatal smoking predicted the co-occurrence of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and ADHD when high levels of both were contrasted with absence of both. This suggests that maternal prenatal smoking, to the extent that it is a causal factor, may affect behavior much more seriously than initially shown in specificity studies. However, such a conclusion may be premature because that analysis did not inform us if maternal prenatal smoking was related specifically to the co-occurrence of both behavior problems or whether it was driven by its association with either behavior problem because we do not know if the combined group differed from the ODD-only or ADHD-only groups. Thus whether maternal prenatal smoking is related to the co-occurrence of behavior problems remains an open question in this literature.

In contrast to childhood and adolescence studies, there is a more limited number of early childhood studies and they tend to focus on symptoms rather than diagnoses. Tremblay et al. (2004) reported an association with early childhood trajectories of PA across time, and Romano et al. (2006) found an association between maternal prenatal smoking and hyperactive symptoms from age 2 to 7, but both studies focused on one externalizing behavior problem. Other studies focused on multiple behaviors. Orlebeke, Knol, and Verhulst (1997) and Williams et al. (1998), using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) in large cohort studies of 3-year-old and 4 to 6-year old children, respectively, found associations with externalizing behavior problems (aggressive, overactive, oppositional) but not with internalizing behavior problems (withdrawn, anxious, depressed). Day, Richardson, Goldschmidt, and Cornelius (2000) reported significant associations of third trimester exposure with scores on each of the subscales of the Toddler Behavior Checklist (Physical Aggression, Oppositional Behavior, Immaturity, and Emotionality) and Activity level assessed with the Routh Activity Scale. Wakschlag, Leventhal et al. (2006) noted a persistent association between maternal prenatal smoking and disruptive behaviors during early childhood. None of these multiple behavior studies examined co-occurrence. Thus there also remains a need in the early childhood literature to examine whether maternal prenatal smoking is specifically associated with the co-occurrence of problem behaviors.

From a developmental perspective, early onset of externalizing behavior has been associated with the poorest outcomes (Brame, Nagin, & Tremblay, 2001; Lacourse et al., 2006; Moffitt, 1993; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2002). In addition, co-occurring externalizing behaviors during middle childhood have been associated with the poorest behavioral outcomes during adolescence and adulthood (Lacourse et al., 2006; Lahey, McBurnett, & Loeber, 2000; Séguin et al., 2004). However, co-occurring behavior problems may be etiologically different from individual behavior problems, with their own social, sociodemographic and biological precursors (Waschbusch, 2002). Yet, we know very little about the prenatal markers of co-occurring behavior problems in general. Given that maternal prenatal smoking has been clearly associated with several single externalizing problems across development, in the present study, we test the hypothesis that maternal prenatal smoking is associated with co-occurring externalizing problems. Specifically we predict that maternal prenatal smoking will be associated to the co-occurrence of PA and HI in contrast with the absence of both, PA-only, and HI-only in a large early childhood sample.

Methods

Participants

The children of this study were born in 1997/1998 in the province of Québec, Canada and participate in the Québec Longitudinal Study of Children’s Development. This sample excluded very remote regions of the province populated mainly by aboriginal people (2.1% of live births), babies for whom gestational age could not be computed (1.3%), babies born in a different territory but whose parents reside in Québec (4.5%), and very premature babies (<24 weeks) and babies for whom there were delays in filing the birth records in the Master Birth Registry on time for the first assessment, i.e. babies born after 42 weeks gestation (0.1%; for full details, see Jetté & Des Groseilliers, 2000). A total of 2940 infants met inclusion criteria and were selected through a region-based stratification procedure (Jetté & Des Groseilliers, 2000). Of this original selection, a number of families could not be included in the initial 5 month-assessment for the following reasons: (1) Families not found on time (incorrect address/tel no.) (n=172, 5.9%); (2) Families excluded (total n=93, 3.2%) because of death of the baby (n=5), because of participation in other longitudinal studies (n=5), because they had no command of either English or French language (n=81), or because the instruments of the study were not designed to adequately measure development of children with severe physical or mental handicaps (n=2); (3) Families that could not be reached (n=14, 0.5%); (4) Families who declined participating (n=438, 16.4%). 2223 Families (75.6%) took part in the first assessment, which took place when the infants were 5 months old. Demographic characteristics of this Québec sample were comparable to those of a large Canadian sample consisting of 13,439 households which contains sufficient samples from each of the 10 Canadian provinces (Human Resources Development Canada, 1996: National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, 1994–1995). Assessments relevant to this study took place at 17, 30 and 42 months. Parental informed consent was obtained before every assessment. 478 participants had either dropped out since the initial assessment at 5 months or had missing values for PA, HI or one or more predictor variables. Thus, the final study sample consisted of 1745 children (78.5% of families enrolled at 5 months). Table 1 indicates that, despite the fact there was a slight tendency for less advantaged families to drop out or have missing values on relevant variables, demographic characteristics were largely similar for in- and excluded families.

Measurements

Maternal prenatal smoking

When the child was 5 months of age, mothers filled out a number of questionnaires. One set of questions concerned substance use (alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drugs) during pregnancy. The questions assessing smoking behavior during pregnancy were straightforward, ‘Did you smoke during pregnancy?’ and ‘How many cigarettes/day did you smoke whilst pregnant?’ We also asked when during pregnancy the mother had smoked, i.e. (only) in the first, second or third trimester or throughout pregnancy. These questions are similar to those found in most other assessment instruments (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Questionnaire, see Beck et al., 2002) and like those found in most other studies (particularly those assessing large samples, e.g. Button et al., 2005; Fergusson et al., 1998; Maughan et al., 2004; Thapar et al., 2003; Wakschlag et al., 1997; Wakschlag & Hans, 2002). Because amount of cigarettes reportedly smoked tends to be a ‘rounded’ number, e.g. 5, 10, 15, etc, mothers were classified into 1 of 4 groups (0, 1–9, 10–19, or ≥20 cigarettes/day). This or similar classifications have been used in most other studies investigating smoking during pregnancy (e.g. Button et al., 2005; Fergusson et al., 1998; Maughan et al., 2004; Thapar et al., 2003; Wakschlag et al., 1997; Wakschlag & Hans, 2002). Although there is a risk for a social desirability bias, several studies have indicated a relatively strong association between retrospective self-report and blood/urine cotinine-levels (i.e. the main nicotine metabolite) (e.g. Law et al., 2003; Pickett, Rathouz, Kasza, Wakschlag, & Wright, 2005). Further reliance on self-report measures may be inferred from the strong relation between the amount reportedly smoked during pregnancy and birth weight (e.g. Huijbregts et al., 2006; Kramer et al., 2001). Other studies have shown that whereas for some prenatal exposures (e.g. alcohol, drugs) higher levels were reported postnatally than antenatally, this was not the case for tobacco exposure, which might indicate that smoking is considered a more habitual behavior that is more reliably recalled (e.g. Jacobsen, Chiodo, Sokol, & Jacobson, 2002). For the current analyses, 1307 (74.9%) mothers reported not to have smoked during pregnancy, 202 (11.6%) reported to have smoked 1–9 cigarettes/day, 174 (10%) between 10 and 19, and 62 (3.6%) reported to have smoked 20 or more cigarettes/day during pregnancy.

Physical aggression and hyperactivity-impulsivity

Maternal ratings of child behavior were obtained with the use of an early childhood behavior scale from the Canadian National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth (Statistics Canada, 1995), which incorporates items from the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 2–3 (Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987), the Ontario Child Health Study Scales (Offord, Boyle, & Racine, 1989), and the Preschool Behavior Questionnaire (Tremblay, Desmarais-Gervais, Gagnon, & Charlebois, 1987). In order to assess PA mothers were asked at 17, 30 and 42 months to indicate whether the child: (1) hits, bites, kicks; (2) fights; and (3) bullies others. The items for HI were: (1) can’t sit still, is restless (or hyperactive), (2) fidgets, (3) cannot settle down to do anything for more than a few moments, (4) is impulsive, acts without thinking, and (5) has difficulty waiting for turn in games. The first three representing hyperactivity, and the latter two representing impulsivity. The items were scored as follows: never or not true (score = 0), sometimes or somewhat true (score = 1), or often or very true (score = 2). The items were summed to obtain PA (range = 0 to 6) and HI scores (range = 0 to 10). The internal consistency values (Cronbach’s α) for PA were 0.80 at 17 months, 0.82 at 30 months, and 0.72 at 42 months. For HI they were 0.75, 0.75, and 0.71, respectively. The scales were shown to have good discriminant validity in the prediction of different types of adolescent criminal behaviors (Broidy et al., 2003; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999), and although correlated, the PA and HI scales were related in predictable ways with mother and child reports of CD and ADHD, respectively (Séguin et al., 2004). Their validity in early childhood is also well established (Tremblay et al., 2004; Romano et al., 2006).

Control variables

Potential confounders of associations between maternal prenatal smoking and early behavior problems were selected from four key domains: demographic factors (age at birth of first child, family status (separation/divorce: yes/no), presence of siblings, family income, maternal education); perinatal factors (alcohol and drug exposure during pregnancy, birth weight); family functioning and parenting (hostile reactive parenting, responsiveness, involvement), and parental background and mental health (mother’s and father’s history of antisocial behavior, maternal depression). Mothers provided information on most of these factors when their child was 5 months of age and again when their child was 17 months of age.

Family income was indicated on a 7-point scale (1 = less than $10,000 (Canadian) to 8 = more than $80,000, as was maternal education (1 = no high school diploma to 7 = university degree). The poverty line in Canada is situated at around $15,000 per capita (Statistics Canada, 2006).

Perinatal factors included exposure to illegal drugs (yes/no) and alcohol (7-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘daily’) during pregnancy and birth weight. Birth weight and gestational age were derived from birth records. Birth weight for gestational age was standardized within gender for each week of gestation using Canadian norms (Kramer et al., 2001).

Parenting measures were obtained by observing the mother-child dyad during home visits at 5 and 17 months using the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME)-Infant version (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984). The observations were carried out by trained observers who spent about 3 hours in the home to complete a battery of questionnaires and tests. These observers received a one-week training session and were closely supervised during the data collection. Three scales were obtained: hostile reactive parenting (e.g. “talks negatively about her child,” “shouts at her child,” “hits or physically punishes her child”; α=0.43 at 5 months and 0.73 at 17 months), responsiveness (e.g. “responds verbally to child’s vocalizations or verbalizations,” “tells child name of object or person during the visit,” “spontaneously praises the child at least twice”; α=0.85 at 5 months and 0.83 at 17 months), and involvement (e.g. “provides toys that challenge child to develop new skills,” “structures child’s play periods”; α=0.85 at 5 months and 0.88 at 17 months). Scores for each item on each scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time). Only the scale score for hostile reactive parenting at 17 months was used because of the low internal reliability of this scale at 5 months. Mean scores across the 5 and 17 months assessments were used for the responsiveness and involvement scales.

Family functioning (at 5 and 17 months) was assessed with a scale containing 12 items measuring communication, problem resolution, control of disruptive behavior, and showing and receiving affection (Statistics Canada, 1995). Scores per item could be 0 (‘never’), 1 (‘sometimes’), or 2 (‘often’), thus ranging from 0 to 36 on the scale. The Cronbach α’s were 0.86 (5 months) and 0.98 (17 months).

In order to assess history of antisocial behavior, both parents completed a questionnaire at the 5-month assessment. The questionnaire included items related to childhood/adolescence (i.e. the period before the end of high school) and items related to adulthood (Zoccolillo, 2000; see also Tremblay et al., 2004), and was largely derived from the NIMH-Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins, Helzer, Croughan, & Radcliff, 1981). Childhood/adolescence items included ‘starting fights,’ theft, involvement with youth protection or police, expulsion or suspension from school, truancy, and running away from home. Adult items included arrests (other than for traffic violations), being fired from a job (excluding layoffs for lack of work), trouble at work, with family, or with the police due to drug or alcohol abuse, ‘starting fights’ (fathers), and ‘hitting or throwing things at the spouse or partner’ (mothers). Adolescent and adult scores (0 = no, 1 = yes) were summed for mothers and for fathers. Internal reliability for mother’s items was 0.54 (Cronbach’s α) and 0.59 for father’s items. Latent class analysis identified 3-class models for both mothers ((1) not antisocial, (2) moderately antisocial, (3) antisocial) and fathers ((1) not antisocial, (2) antisocial as an adolescent but not as an adult, (3) moderately antisocial as an adolescent, antisocial as an adult). The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used for report of symptoms associated with depression (at 5 and 17 months).

Studies have shown that all these factors are associated with increased risk for physical aggression, hyperactivity, CD- and ADHD-symptoms and with prenatal maternal smoking (e.g. Biederman, Milberger, & Faraone, 1995; Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Huijbregts et al., 2006; Linnet et al., 2003; Maughan et al., 2004; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Tremblay et al., 2004; Nagin & Tremblay, 2001; Romano et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2005). Apart from the dichotomous variables (i.e. gender, presence of siblings, drug use during pregnancy, family status), all scores were standardized for statistical analyses.

Data analyses

Assignment to trajectories

Scores from the three assessment points were analyzed to identify distinctive behavioral trajectories across time (Nagin, 1999, 2005; Nagin & Tremblay, 2001). Rather than to assume that all children follow the same developmental pattern, this methodology identifies different groups of individuals who tend follow similar patterns over time. For example, some children may never show a given problem behavior (intercept model or zero order polynomial), others may show constant high levels (also intercept model), and others may increase or decrease over time (e.g., linear – 1st, quadratic – 2nd, or cubic – 3rd order polynomials). The methodology can also be adapted to accommodate various data distributions (i.e., binary, censored normal, zero-inflated Poisson, and count data). The trajectory methodology uses all available developmental data points and assigns individuals to trajectories on the basis of a posterior probability rule. Resulting groups are meant to represent approximations of an underlying continuous process. In order to identify the model that best represents development of a specific behavior during a given time frame, models with a varying number of trajectories are estimated. Model selection is dependent on a combination of statistical and investigator-guided concerns. Besides a need to determine the best model for the data distribution, key decisions are also based on Bayesian fit indices for model selection in accordance to procedures described by Nagin (2005), e.g. the higher the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the better. The optimal model is thus also determined by adding trajectories to the model until the BIC ceases to improve. The investigator would then have enough information to determine the best model.

A key output of model estimation is the posterior probability of group membership. For each trajectory group this probability measures the likelihood of an individual of belonging to that trajectory group based on observations across assessments. In other words, 100% accuracy in classification is not assumed nor required. For example, in the case of an individual who scores high on hyperactivity at all assessment periods, the posterior probability of membership to the chronic group would be high whereas the probability of membership to the low trajectory group would be near 0. Participants can be assigned to the trajectory group for which they show the highest probability of belonging. Ideally, the posterior membership probability should be near 1 for this trajectory group. Further, when trajectories are joined, conditional and joint probabilities can be used to further describe the relationship between the joint factors. Posterior probabilities will then be applied to weight PA, HI and their combination when they enter further analyses (see Séguin et al., 2004).

Prediction of physical aggression, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and their co-occurrence

Weighted multinomial regressions were conducted with PROC CATMOD in SAS v.8.2. (SAS Institute Inc., 2001). First, weighted multinomial regressions were conducted separately on PA and HI between ages 17 and 42 months for descriptive purposes. The influence of maternal prenatal smoking on these behaviors was investigated in analyses with and without control variables.

For the second set of analyses predicting PA and HI between ages 17 and 42 months, we contrasted, in weighted multinomial regression, those children who were high on both PA and HI (combined group), to those who were only high on PA (PA only group), to those only high on HI (HI only group) and to the remainder of the sample.

Results

Assignment to trajectories

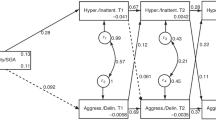

Models with between 2 to 5 trajectories and varied shapes for each trajectory were compared using BIC for both PA and HI. Three trajectories were modeled for PA between ages 17 and 42 months using a zero-inflated Poisson distribution: a consistently low, a moderate and rising, and a high and rising trajectory, each representing respectively 25, 50, and 25% of the sample, all of these were best modeled using a linear trend except for the low group which was best represented by a constant term (Fig. 1, left panel). The shape and level of the PA trajectories were very similar to those we identified in Tremblay et al., 2004, in a smaller sample using the same measures. It reveals that most of the children show an increase of physical aggression over time, which is consistent with other longitudinal and cross sectional studies of early childhood.

Four trajectories were modeled for HI using a censored normal distribution: consistently low, low to moderate, moderate to high and chronic HI, representing respectively, 12, 45, 37, and 6% of the sample. All were best modeled by a constant term except for the low to moderate group that was best modeled with a quadratic trend (Fig. 1, right panel).Thus in contrast to PA, HI in early childhood appears to be more stable in level across time, with very few children being atypically high.

Observed and predicted means for developmental trajectories of physical aggression (PA) and Hyperactivity-impulsivity (HI) between ages 17 and 42 months. *Physical aggression: H-R = high-rising; M-R = moderate-rising; C-L = consistently low; Hyperactivity-Impulsivity: H-C = high-chronic; M-H = moderate-high; L-M = low-moderate; C-L = consistently low. Data courtesy of the Institut de la Statistique du Québec

In the current models for PA and HI the average posterior probability for the assigned trajectory group ranged between .75 and .83, thereby indicating good fit (Nagin, 1999, 2005). Further, a close match of predicted and observed means shown in Fig. 1 also illustrates this good fit. Models with three trajectories for PA and four trajectories for HI have also produced the best fit in studies using other samples that included children in early childhood (e.g. Tremblay et al., 2004; Côté et al., 2006; Romano et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2005).

Physical aggression

A first multinomial regression revealed that maternal prenatal smoking significantly predicted PA. In an analysis without control variables, both the odds ratio (OR) contrasts between high and low PA [OR=1.49 (95% CI: 1.25 to 1.75), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 21.0\), p<.001] and between high and moderate PA [OR=1.27 (95% CI: 1.11 to 1.45), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 12.8\), p<.001] were significantly predicted by maternal prenatal smoking (\(\chi _{(2)}^2 = 23.6\), p<.001; see also Table 2). The ORs represent one categorical increase in maternal prenatal smoking, i.e. from ‘0 cigarettes/day’ to ‘1–9,’ ‘1–9’ to ‘10–19,’ and from ‘10–19’ to ≥20 cigarettes/day.

Maternal prenatal smoking was also a significant predictor of PA in a multinomial regression with control factors [\(\chi _{(2)}^2 = 8.4\), p=.015]. The ORs were reduced to 1.33 (95% CI: 1.10 to 1.61) [\(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 8.1\), p=.004] for the contrast between high and low PA, and to 1.16 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.35) [\(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 3.3\), p=.057] for the contrast between high and moderate PA. Other significant predictors of PA between ages 17 and 42 months were gender [\(\chi _{(2)}^2 = 22.0\), p<.001], presence of siblings [\(\chi _{(2)}^2 = 86.2\), p<.001], and hostile reactive parenting (by the mother) [\(\chi _{(2)}^2 = 23.6\), p<.001].

Hyperactivity-impulsivity

A first multinomial regression predicting HI without control variables revealed significant contrasts between high and low HI [OR=1.75 (95% CI: 1.32 to 2.33), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 15.1\), p<.001], between high and low-moderate HI [OR=1.49 (95% CI: 1.20 to 1.85), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 13.1\), p<.001] and high and moderate-high HI [OR=1.25 (95% CI: 1.01 to 1.56), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 4.1\), p=.043], resulting in an overall significant effect (\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 22.8\), p<.001). In a second multinomial regression with control variables the association of maternal prenatal smoking with HI was strongly attenuated, although the overall effect was still not too far from significance [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 5.8\), p=.12] (see also Table 2). This attenuation can also be seen in the contrasts between high and low HI [OR=1.38 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.91), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 3.8\), p=.052], between high and low-moderate HI [OR=1.27 (95% CI: 0.98 to 1.63),\(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 3.3\), p=.070] and high and moderate-high HI [OR=1.13 (95% CI: 0.88 to 1.46), \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 1.0\), p=.327]. The remaining significant predictors of HI between ages 17 and 42 months were gender [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 31.1\), p<.001], hostile reactive parenting (by the mother) [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 42.6\), p<.001], maternal depression [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 12.4\), p=.006], and age of the mother when she had her first child [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 11.0\), p=.012].

Combining physical aggression and hyperactivity-impulsivity

Although distinct, the trajectories of PA and HI were moderately but significantly related (\(\chi _{(6)}^2 = 114.5\), p<.001; Spearman r=.245, p<.001). The conditional probabilities for PA and HI in Table 3 show that, with higher PA or HI, there is also a higher probability of HI and PA, respectively. The conditional probabilities further reveal an asymmetry in the association in that most high HI children were likely to be high PA, but that most high PA children are not likely to be high HI. Table 3 also shows the joint probabilities of displaying particular levels of PA and HI simultaneously. There are 12 cells (3 PA × 4 HI). In order to test the contrasts relevant to our research question, i.e. that maternal prenatal smoking might specifically predict co-occurring PA and HI as opposed to PA only or HI only, these 12 groups were collapsed into 4 groups representing the combined group (PA3HI4), the high PA only group (PA3HI1 + PA3HI2 + PA3HI3), the high HI only group (PA1HI4 + PA2HI4), and the remainder of the sample (PA1HI1 + PA1HI2 + PA1HI3 + PA2HI1 + PA2HI2 +PA2HI3) (Table 4). For the next analysis, these four groups will constitute our dependent variable.

In order to be able to conclude that prenatal smoking specifically predicts co-occurring PA and HI the a priori contrasts of all groups to the combined group should be significant. A multinomial regression with the control variables that had featured in the previous separate analyses of PA and HI showed that this was indeed the case. The overall effect of maternal prenatal smoking [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 10.5\), p=.015], and the predictions by prenatal smoking of the contrasts of the combined group with the PA only group [OR=1.39, 95% CI to 1.01 to 1.92, \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 4.0\), p=.047], with HI only group [OR=1.72, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.86, \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 4.8\), p=.029], and with the remainder of the sample [OR=1.59, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.17, \(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 8.4\), p=.004], were all significant (see also Table 2). Although additional contrasts were not significant, the contrast between the PA-only group and ‘the remainder of the sample’- group approached significance [\(\chi _{(1)}^2 = 3.0\), p=.08]. Other significant and independent predictors of the combined group were gender [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 18.0\), p<.001], presence of siblings [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 59.3\), p<.001], and hostile reactive parenting (by the mother) [\(\chi _{(3)}^2 = 22.5\), p<.001].

Discussion

The results of this study of early childhood show that maternal prenatal smoking was associated with PA but not with HI in covariate regression analyses when PA and HI were examined separately. When PA and HI were combined, a contrast between the PA-only group and the remainder of the sample, which was neither high on PA or HI, fell short of significance. However, maternal prenatal smoking predicted co-occurring elevated levels of PA and HI. Therefore the key finding of this study is that maternal prenatal smoking predicted high PA, but largely when it is co-occurring with high HI. Had we just examined PA and HI separately, as has often been done in studies of specificity, we would have missed the fact that HI is also sensitive to maternal prenatal smoking, even after controlling for several confounding variables, but only when it is combined with PA.

The first implication of these findings is that maternal prenatal smoking may be associated with the most severe forms of PA and HI, i.e. their combination, in early childhood. Second, the fact that maternal prenatal smoking predicts co-occurring PA and HI may be considered an important finding in light of evidence indicating that multiple co-occurring behavior problems at an early age are associated with a higher risk of persistent antisocial problems (Brame et al., 2001; Broidy et al., 2003; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Lacourse et al., 2006; Lahey et al., 2000; Moffitt, 1993; Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996), as well as with several other functional impairments (Waschbusch, 2002; Séguin et al., 2004). Finally, the risk factors identified for these combined behavior problems, are largely modifiable.

Our study replicates the reports from Orlebeke et al. (1997), Williams et al. (1998), Day et al. (2000), and Tremblay et al. (2004), based largely on early childhood behavior problems. However, we extend these findings because none of those early childhood studies had tested for the prediction of specific behavior problems or for the specificity of their combination. Tremblay et al. (2004) covered the same developmental period and used the exact same PA scale as we did here on another sample. We both found that the association between maternal prenatal smoking and PA was not explained by control variables. However, our results for HI appear to contrast slightly with those of Romano et al. (2006) who reported that the association between maternal prenatal smoking and hyperactivity was not explained by control variables. There are a number of key differences between the current study and Romano et al. (2006). Besides using a different sample, we included impulsivity along with hyperactivity items, and focused exclusively on behavior during early childhood. Thus, in the current study the effects of maternal prenatal smoking on HI were largely explained by control variables. It is possible that control variables have a greater effect on the impulsivity component of HI than on the hyperactivity component. We note that our results appear to be consistent with those of Wakschlag, Leventhal et al. (2006), who also failed to find a relation of maternal prenatal smoking but with ADHD, which includes impulsivity. Because of our goal for a strict test for specificity of effects on PA, it was more conservative to have a combination of impulsivity and hyperactivity items in our scale. Alternately, by having information extending beyond the early childhood period to estimate trajectories Romano et al. (2006) may have more accurately identified children for whom maternal prenatal smoking matters beyond the effects of control variables. Despite this limitation to early childhood, and despite the fact that we cannot claim to have accounted for all possible control variables (examples include exposure to environmental smoking postnatally and forms of parental psychopathology other than maternal depression and parental history of antisocial behavior such as parental ADHD), this study replicates and extends all previous studies by providing an empirical basis for how the association of prenatal smoking to both PA and HI may manifest itself. It is now much more clear that studies need to examine co-occurrence of behavior problems.

There is a leap in drawing parallels between early childhood symptoms to DSM-based disorder, i.e., from PA to CD and from HI to ADHD. CD is characterized by aggression to people and/or animals, deceitfulness or theft, vandalism and serious rule violations whereas ADHD is characterized by hyperactivity, behavior disinhibition (or impulsivity), and inattention and distractibility (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). It is not yet clear to what extent behavior problems during the early childhood years map onto ADHD and CD symptoms during later childhood and (antisocial) behavior problems during adolescence and adulthood, although we have shown that childhood PA trajectories and hyperactivity trajectories were respectively related to CD and ADHD measured in adolescence (Séguin et al., 2004). But manifestation of PA and HI symptoms are often not sufficient to warrant diagnoses. We also note that behavior problems during the early childhood years tend to be more common and typically decline over time (Côté et al., 2006; Romano et al., 2006; Bongers, Koot, Van Der Ende, & Verhulst, 2003).

A number of pioneering studies showed that behavior problems later in life (ranging from school-age to adulthood) could already be identified during early childhood (e.g. Campbell et al., 1986; Keenan & Wakschlag, 2000), but only recently a number of studies have started to show, particularly with respect to HI, a significant consistency in the likelihood to display (very) high levels from age 1 1/2 years onwards (e.g. Romano et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2005). With respect to PA, there is a larger group of very young children showing rather high levels, but most of them will use less PA from early school age onwards (e.g. Côté et al., 2006; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004; Shaw et al., 2005). Such general trends might also underlie differences in number of groups identified by the trajectory methodology in samples with different age ranges. Whereas our three PA-groups were consistent with the three groups identified by some authors (e.g. Côté et al., 2006) covering early and middle childhood, other authors identified more than three groups for this period (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004; Shaw et al., 2005). However, most children will not yet have finished learning alternative strategies (i.e. have undergone ‘socialization of aggression,’ Tremblay, 2003) between 17 and 42 months, so the expected ‘desisting’ patterns of PA will not yet be evident. One thing the abovementioned studies have in common is that they show a degree of consistency between early and middle childhood conduct problems, i.e. children with chronic PA during middle childhood generally had high PA levels during early childhood as well. This, in turn, emphasizes the importance of searching for predictors of co-occurring early childhood behavior problems: children most at risk of subsequent behavior problems might be those who display both high PA and high HI at this stage.

The combination of conduct problems and hyperactivity-impulsivity-attention problems has been distinguished from their pure forms at a number of levels (Waschbusch, 2002). Although research has again mainly focused on older children with diagnosed disorders rather than the combination of behaviors such as PA and HI (but see Séguin, Arseneault, Boulerice, Harden, & Tremblay, 2002; Séguin et al., 2004), evidence has been provided for a number of etiological and developmental differences between the comorbid and individual conditions. For example, greater behavioral and autonomic nervous system reactivity in response to provocation has been shown in the comorbid compared to the separate conditions (Waschbusch, 2002). Children with CD+ADHD were also shown to have lower baseline sympathetic arousal than children with the separate disorders (specifically those with ADHD only; Herpertz et al., 2001). There is also evidence for differences in patterns of brain activity between CD+ADHD and the separate conditions (Banaschewski et al., 2003) and for specific heritable risk of CD+ADHD (Dick, Viken, Kaprio, Pulkkinen, & Rose, 2005; Thapar, Harrington, & McGuffin, 2001). Several studies have shown that specific family psychosocial characteristics (e.g. parent-child conflict; parental psychopathology) specifically predict CD+ADHD or predict CD+ADHD more strongly than the separate conditions (e.g. Burt, Krueger, McGue, & Iacono, 2003; Pfiffner, McBurnett, Rathouz, & Judice, 2005). Thus, although extrapolation to CD and ADHD must be done with caution, the results of the present study support an etiological basis for the combined behavior problems in an early childhood sample.

Finally, in addition to prenatal maternal smoking, we found that maternal hostile- reactive parenting was also associated with co-occurring PA and HI beyond its effects on the separate behaviors. Hostile-reactive parenting and similar ‘negative’ parenting behaviors have been associated with children’s PA and HI levels in earlier studies (e.g. Côté et al., 2006; Romano et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2005; Tremblay et al., 2004), Negative parenting has also been related to the failure of training programs aimed at improving child conduct problems (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001). This association could be seen as resulting from the impact of maternal behavior on their child’s behavior. However, they may also reflect, at least in part, parent’s reactions to their child’s behavior. For instance, when faced with conduct problems, mothers of preschoolers at risk for ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder tend to resort to more negative parenting strategies (Cunningham & Boyle, 2002). Furthermore, mothers hostile-reactive parenting toward their 5 month-old infants has been found to be partly driven by their infant’s difficult temperament (Boivin et al., 2005).

Our finding that maternal hostile-reactive parenting is associated with an increased risk of co-occurring PA and HI may thus reflect the increased challenge of parenting when a child displays multiple behavior problems (cf. Seipp & Johnston, 2005). This pattern could lead to the establishment of a family coercive process and the further learning of anti-social behaviors by the child. However, the state of evidence precludes any definite conclusions at this point, and there is a clear need to better document the early dynamics of negative parenting and externalizing problems in early childhood.

To the extent that they may be involved in causation, the good news is that prenatal maternal smoking and hostile-reactive parenting could be significantly attenuated in prevention and intervention programs. The fact that the effects of smoking during pregnancy on both PA and PA+HI were robust, added to the evidence that PA+HI increases the risk for continued serious behavior problems, emphasizes the importance of smoking cessation during pregnancy (for a review on effectiveness of cessation programs, see Lumley, Oliver, Chamberlain, & Oakley, 2004). Considering the high prevalence of prenatal smoking (around 25% in Western countries), it will be important to further refine the identification of families most at risk of having children with a prepotency to develop co-occurring PA and HI. Our results further confirm that hostile-reactive parenting should be targeted in preventive intervention aimed at children with early multiple behavior problems. However, because parenting interventions often are the least effective in multiple-risk families (for a review, see Hutchings & Lane, 2005), including those characterized by prenatal smoking (Vuijk, van Lier, Huizink, Verhulst, & Crijnen, 2006), cessation programs targeting the most vulnerable families should be emphasized, intensified, and given appropriate means to succeed.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Edelbrock, C. S., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Empirically based assessment of the behavioral/emotional problems of 2- and 3- year-old children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15, 629–650.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., pp. 78–85). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Banaschewski, T., Brandeis, D., Heinrich, H., Albrecht, B., Brunner, E., & Rothenberger, A. (2003). Association of ADHD and conduct disorder – brain electrical evidence for the existence of a distinct subtype. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 356–376.

Beck, L. F., Morrow, B., Lipscomb, L. E., Johnson, C. H., Gaffield, M. E., Rogers, M. et al. (2002). Prevalence of selected maternal behaviors and experiences: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) 1999. CDC Surveillance Summaries, 51, 1–27.

Biederman, J., Milberger, S., & Faraone, S. V. (1995). Family-environment risk factors for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A test of Rutter’s indicators of adversity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 464–470.

Boivin, M., Pérusse, D., Dionne, G., Saysset, V., Zoccolillo, M., Tarabulsy, G. et al. (2005). Parent’s perceptions and self-assessed behaviors toward their 5-month-old infants in a large twin and singleton sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 612–630.

Bongers, I. L., Koot, H. M., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 179–192.

Brame, B., Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Developmental trajectories of physical aggression from school entry to late adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 389–394.

Braun, J., Kahn, R. S., Froehlich, T., Auinger, P., & Lanphaer, B. P. (2006). Exposures to environmental toxicants and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in US children. Environmental Health Perspectives, ehp. 9478 (available at http://dx.doi.org/).

Brennan, P., Grekin, E., & Mednick, S. (1999). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and adult male criminal outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 215–219.

Broidy, L. M., Nagin, D. S., Tremblay, R. E., Bates, J. E., Brame, B., Dodge, K. A. et al. (2003). Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology, 39, 222–245.

Burt, S. A., Krueger, R. F., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. (2003). Parent-child conflict and the comorbidity among childhood externalizing disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 505–513.

Button, T. M. M., Thapar, A., & McGuffin, P. (2005). Relationship between antisocial behaviour, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and maternal prenatal smoking. British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 155–160.

Campbell, S. B., Breaux, A. M., Ewing, L. J., & Szumowski, E. K. (1986). Correlates and predictors of hyperactivity and aggression: A longitudinal study of parent-referred problem preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 14, 217–234.

Campbell, S. B., Shaw, D. S., & Gilliom, M. (2000). Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 467–488.

Côté, S., Vaillancourt, T., LeBlanc, J. C., Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). The development of physical aggression from toddlerhood to pre-adolescence: A nation-wide longitudinal study of Canadian children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 68–82.

Cunningham, C. E., & Boyle, M. H. (2002). Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Family, parenting and behavioral correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 555–569.

Day, N. L., Richardson, G. A., Goldschmidt, L., & Cornelius, M. D. (2000). Effects of prenatal tobacco exposure on preschoolers’ behavior. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 21, 180–188.

Dick, D. M., Viken, R. J., Kaprio, J., Pulkkinen, L., & Rose, R. J. (2005). Understanding the covariation among childhood externalizing symptoms: Genetic and environmental influences on conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 219–229.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 313–337.

Fergusson, D. M., Woodward, L. J., & Horwood, L. J. (1998). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 721–727.

Herpertz, S. C., Wenning, B., Mueller, B., Qunaibi, M., Sass, H., & Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. (2001). Psychophysiological responses in ADHD boys with and without conduct disorder: Implications for adult antisocial behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1222–1230.

Huijbregts, S. C. J., Séguin, J. R., Zelazo, P. D., Parent, S., Japel, C., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Interrelations between maternal smoking during pregnancy, birth weight and sociodemographic factors in the prediction of early cognitive abilities. Infant and Child Development, 15, 593–607.

Human Resources Development Canada and Statistics Canada. (1996). Growing up in Canada: National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. http://www.statcan.ca/english/Dli/Data/Ftp/nlscy.htm.

Hutchings, J., & Lane, E. (2005). Parenting and the development and prevention of child mental health problems. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18, 386–391.

Jacobsen, S. W., Chiodo, L. M., Sokol, R. J., & Jaconson, J. L. (2002). Validity of maternal report of prenatal alcohol, cocaine, and smoking in relation to neurobehavioral outcome. Pediatrics, 109, 815–825.

Jensen, P. S., Martin, D., & Cantwell, D. P. (1997). Comorbidity in ADHD: Implications for research, practice, and DSM-V. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 147–158.

Jetté, M., & Des Groseilliers, L. (2000). Survey Description and Methodology. In Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Québec (ELDEQ 1998–2002) (Vol. 1, No. 1). Québec: Institut de la Statistique du Québec. http://www.jesuisjeserai.stat.gouv.qc.ca/doc_tech_an.htm.

Keenan, K., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2000). More than the terrible twos: The nature and severity of behavior problems in clinic-referred preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 33–46.

Kotimaa, A. J., Moilanen, I., Taanila, A., Ebeling, H., Smalley, S. L., McGough, J. J. et al. (2003). Maternal smoking and hyperactivity in 8-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 826–833.

Kramer, M. S., Platt, R. W., Wen, S. W., Joseph, K. S., Allen, A., Abrahamowicz, M., Blondel, B., & Breart, G.; Fetal/Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. (2001). A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics, 108, e35.

Lacourse, E., Nagin, D. S., Vitaro, F., Côté, S., Arseneault, L., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Prediction of early-onset deviant peer group affiliation: A 12-year longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 562–568.

Lahey, B. B., McBurnett, K., & Loeber, R. (2000). Are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder developmental precursors to conduct disorder? In A. J. Sameroff, M. Lewis, & S. M. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychopathology (2nd ed., pp. 431–446). New York: Kluwer Academic.

Law, K. L., Stroud, L. R., LaGasse, L. L., Niaura, R., Liu, J., & Lester, B. M. (2003). Smoking during pregnancy and newborn neurobehaviour. Pediatrics, 111, 1318–1323.

Linnet, K. M., Dalsgaard, S., Obel, C., Wisborg, K., Hendriksen, T. B., Rodriguez, A. et al. (2003). Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: Review of the Current Evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1028–1040.

Lumley, J., Oliver, S. S., Chamberlain, C., & Oakley, L. (2004). Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 4, CD001055.

Maughan, B., Taylor, A., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2004). Prenatal smoking and early childhood conduct problems: Testing genetic and environmental explanations of the association. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 836–843.

Mick, E., Biederman, J., Faraone, S. V., Sayer, J., & Kleinman, S. (2002). Case-control study of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and maternal smoking, alcohol use, and drug use during pregnancy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 378–385.

Milberger, S., Biederman, J., Faraone, S. V., Chen, L., & Jones, J. (1996). Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children? American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 1138–1142.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Dickson, N., Silva, P., & Stanton, W. (1996). Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: Natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 399–424.

Nagin, D. S. (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 4, 139–177.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (1999). Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development, 70, 1181–1196.

Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based method. Psychological Methods, 6, 18–34.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2004). Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Serial No. 278, Vol. 69, 4.

Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., & Racine, Y. (1989). Ontario child health study: Correlates of disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 856–860.

Orlebeke, J. F., Knol, D. L., & Verhulst, F. C. (1997). Increase in child behavior problems resulting from maternal smoking during pregnancy. Archives of Environmental Health, 52, 317–321.

Pfiffner, L. J., McBurnett, K., Rathouz, P. J., & Judice, S. (2005). Family correlates of oppositional and conduct disorders in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 551–563.

Pickett, K. E., Rathouz, P. J., Kasza, K., Wakschlag, L. S., & Wright, R. (2005). Self-reported smoking, cotinine levels, and patterns of smoking in pregnancy. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 19, 368–376.

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Räsänen, P., Hakko, H., Isohanni, M., Hodgins, S., Järvelin, M. J., & Tiihonen, J. (1999). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of criminal behavior among adult male offspring in the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 857–862.

Robins, L. N., Helzer, J. E., Croughan, J., & Ratcliff, K. S. (1981). National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38, 381–389.

Romano, E., Tremblay, R. E., Farhat, A., & Côté, S. (2006). Development and prediction of hyperactive symptoms from 2 to 7 years in a population-based sample. Pediatrics, 117, 2101–2110.

SAS Institute Inc. (2001). The SAS System for Windows, v.8.2. Cary, NC: Author.

Seipp, C. M., & Johnston, C. (2005). Mother-son interactions in families of boys with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder with and without oppositional behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 87–98.

Séguin, J. R., Arseneault, L., Boulerice, B., Harden, P. W., & Tremblay, R. E. (2002). Response perseveration in adolescent boys with stable and unstable histories of physical aggression: The role of underlying processes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 481–494.

Séguin, J. R., Nagin, D., Assaad, J.-M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2004). Cognitive-neuropsychological function in chronic physical aggression and hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 603–613.

Shaw, D. S., Lacourse, E., & Nagin, D. S. (2005). Developmental trajectories of conduct problems and hyperactivity from ages 2 to 10. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 931–942.

Silberg, J. L., Parr, T., Neale, M. C., Rutter, M., Angold, A., & Eaves, L. J. (2003). Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy and Risk to boys’ Conduct Disturbance: An examination of the Causal Hypothesis. Biological Psychiatry, 53, 130–135.

Statistics Canada. (1995). Overview of Survey Instruments for 1994–95 Data Collection, Cycle 1. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2006). Income trends in Canada: 1980–2004. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

Thapar, A., Fowler, T., Rice, F., Scourfield, J., van den Bree, M., Thomas, H. et al. (2003). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in offspring. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1985–1989.

Thapar, A., Harrington, R., & McGuffin, P. (2001). Examining the comorbidity of ADHD-related behaviours and conduct problems using a twin study design. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 224–229.

Tremblay, R. E. (2003). Why socialization fails?: The case of chronic physical aggression. In B. B. Lahey, T. E. Moffitt, & A. Caspi (Eds.), Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency (pp. 182–224). New York: Guilford Publications.

Tremblay, R. E., Desmarais-Gervais, L., Gagnon, C., & Charlebois, P. (1987). The Preschool Behaviour Questionnaire: Stability of its factor structure between cultures, sexes, ages and socioeconomic classes. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 10, 467–484.

Tremblay, R., Nagin, D., Séguin, J., Zoccolillo, M., Zelazo, P. D., Boivin, M. et al. (2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics, 114, e43–e50.

Vuijk, P., van Lier, P. A., Huizink, A. C., Verhulst, F. C., & Crijnen, A. A. (2006). Prenatal smoking predicts non-responsiveness to an intervention targeting attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms in elementary schoolchildren. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 891–901.

Wakschlag, L. S., & Hans, S. L. (2002). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and conduct problems in high-risk youth: A developmental framework. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 351–369.

Wakschlag, L. S., Leventhal, B. L., Pine, D. S., Pickett, K. E., & Carter, A. S. (2006). Elucidating early mechanisms of developmental psychopathology: The case of prenatal smoking and disruptive behavior. Child Development, 77, 893–906.

Wakschlag, L. S., Pickett, K. E., Cook, E., Benowitz, N. L., & Leventhal, B. L. (2002). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and severe antisocial behavior in offspring: A review. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 966–974.

Wakschlag, L. S., Pickett, K. E., Kasza, K. E., & Loeber, R. (2006). Is prenatal smoking associated with a developmental pattern of conduct problems in young boys? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 461–467.

Waschbusch, D. A. (2002). A meta-analytic examination of comorbid hyperactive/impulsive/inattention problems and conduct problems. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 118–150.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, J., & Hammond, M. (2001). Social skills and problem-solving training of children with early-onset conduct problems: Who benefits? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 943–952.

Williams, G. M., O’Callaghan, M., Najman, J. M., Bor, W., Andersen, M., & Richards, D. U. C. (1998). Maternal cigarette smoking and child psychiatric morbidity: A longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 102, e11.

Woodward, L. J., Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2002). Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 231–243.

Zoccolillo, M. (2000). Parents’ health and social adjustment: Part II, social adjustment. In Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Québec (ELDEQ 1998–2002) (pp. 37–45). Québec (Qc), Canada: Institut de la Statistique du Québec.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the children and their families for their participation in the study, to l’Institut de la Statistique du Québec, direction Santé Québec, and its partners for data collection and preparation, to Charles Édouard Giguère and Qian Xu for data management, and to Danielle Forest for statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9126-3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Huijbregts, S.C.J., Séguin, J.R., Zoccolillo, M. et al. Associations of Maternal Prenatal Smoking with Early Childhood Physical Aggression, Hyperactivity-Impulsivity, and Their Co-Occurrence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 35, 203–215 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9073-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9073-4