Abstract

Design education traditionally centers around the critique as a pivotal assessment process, fostering the development of both explicit and tacit knowledge within the physical studio environment. Ideally, the critique encourages students to develop their creativity, sharpen their thought processes and refine their technique. This study contributes to the ongoing discourse on technology-enhanced teaching in practice-based design studios by examining the effectiveness of online peer critique as a strategy to capture tacit knowledge and make it explicit in the design learning environment. Drawing on the experiences of 90 undergraduate visual communication design students, findings show the critique process was a collaborative experience which afforded the fluid exchange of both tacit and explicit knowledge. Technology played a key role in this knowledge exchange, giving students a confidence in their creative abilities as observers and participants. The online process facilitated anonymity, enabling open and honest communication, while digital records supported post-critique reflection. Despite challenges, this systematic approach to online peer critique proves beneficial in fully online courses and warrants exploration in physical design studios given that more programs transitioning to blended learning. This research contributes to the discourse on leveraging technology for tacit knowledge construction and learning in design education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: Technology’s influence in the design studio’s evolution

Historically, design education studio pedagogy builds on a master-apprenticeship relationship where the master (design educator) shares their knowledge and skills with the apprentice (student) and guides students in their creative development (e.g., Crowther, 2013; Hart et al., 2011). Design learning is based on “learning-by-doing” (Schön, 1983, 1987), grounded in Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning model of making, observation, feedback and reflection in a physical studio setting. This hands-on approach allows students to immerse themselves in the design process, developing their skills through practice and experience (Crowther, 2013; Shreeve, 2011). This learning through experiences and observation facilitates developing tacit knowledge through practice, observation, reflection, feedback and collaboration (Schön, 1983; Venkatesh & Ma, 2021b; Wong & Radcliffe, 2000).

The Covid pandemic brought a shift towards technological applications in the design studio into sharp focus (Charters & Murphy, 2021; Fleischmann, 2021a; Jones & Lotz, 2021). It “has created a rapid digital transformation of the education sector, which offers an exciting opportunity for dramatically accelerated innovation” (Diefenthaler, 2021, p. 164). There are numerous variations revolving around the pedagogical nucleus of design, particularly in the context of technological innovations that enable design educators, students and tutors to find new ways to share ideas, projects and feedback in a decentralised, interactive and visual way. Recent research has highlighted a growing trend in the application of online technology to enhance the practice-based physical design studio (Brosens et al., 2023; Fleischmann, 2022, 2023) but often depends on the design domain in question (Fleischmann, 2021a). Domains like graphic and communication design, product design, interactive and game design, interior design, and fashion design vary in their acceptance of integrating online technology into practice-based design studios, with practical considerations, especially in more hands-on domains, influencing the level of acceptance (Fleischmann, 2021a).

Not all design educators agree that online platforms can approximate the informal learning opportunities in the physical studio. Fleischmann (2022) found that online technology applications often failed to replicate the nuances of a studio culture that builds a community of practice (Wenger, 1998) through informal interactions and exchange of feedback (Scagnetti, 2017; Shreeve, 2011). The online environment can also disrupt the dialogical learning process that happens in a physical design studio. Tessier and Aubry-Boyer (2021) highlight that “informal interactions and learning from observation seem to be the most problematic aspects of online workshops” (p. 93).

The challenges in teaching design online persist, even in domains seemingly suitable for digital environments like graphic and communication design, and interactive or game design. Educators find it often difficult to replicate essential features of the physical design studio, such as dialogical learning, the critique process and studio culture in online settings (Fleischmann, 2022). Yet, these very features are pivotal for tacit knowledge acquisition and construction in traditional design studio pedagogy (van Dooren et al., 2014; Venkatesh & Ma, 2021a).

The physical “studio environment has always been one of questioning and reflecting and is the ideal environment to facilitate experiential learning. The studio is where students are able to share ideas and question each other’s methods” (van Kampen, 2019, p. 40). Venkatesh (2021) further explains “the studio plays a role in facilitating a dynamic social environment where tacit knowledge is constructed and internalized by the student” (p. 1). Nevertheless, in design education, teachers (as design experts) may struggle to express their expertise clearly (van Dooren et al., 2014; Venkatesh & Ma, 2021b). Venkatesh and Ma (2019) contend that tacit knowledge in design is difficult for students to grasp and sometimes problematic for design educators to make explicit, as it encompasses “aesthetics, intuition, spatial perception, problem solving and sensibility” (p. 1). These forms of tacit knowledge are “constructed by the student, facilitated by the tutors and the interactions in the studio” (p. 1).

One way of making the implicit design knowledge explicit is the critique process in the design studio which is a fundamental characteristic of design education (Crowther, 2013; McLain, 2022; Shreeve et al., 2010) and part of the pathway of becoming, what Schön (1983, 1987) termed, a “reflective partitioner”. During a critique, students present their work-in-progress or final designs to receive explicit feedback. While the educational value of the critique has been a subject of debate and scrutiny over time, several researchers (e.g., Filimowicz & Tzankova, 2017; Jones, 2014; Selçuk et al., 2021) found that the critique process is more transparent and effective in an online environment using peer feedback. Design educators who used online technology for critique sessions during the pandemic also described them as moderately effective (Fleischmann, 2022).

Research has highlighted the significant impact of internet technology on facilitating the transmission and acquisition of tacit knowledge in online settings (e.g., Oztok, 2013; Venkatesh & Ma, 2019). Moreover, Venkatesh (2021) argues that there remains a gap in intensive studies concerning the relationship between tacit knowledge and online learning (p. 123). Therefore, this study contributes to the ongoing discourse surrounding technology-enhanced teaching and learning in practice-based design studios, particularly through its examination of the online peer critique. More specifically, the study explores the effectiveness of online peer critique as a strategy to capture tacit knowledge and make it explicit in the design learning environment.

Tacit knowledge in design education

In design practice, tacit knowledge plays a crucial role, representing the intuitive skills and understanding that designers possess (Son et al., 2024; van Dooren et al., 2014). This unspoken expertise is fundamental to designers’ creative work and problem-solving approaches. Tacit knowledge cannot easily be expressed in words and hence is difficult to communicate (Wong & Radcliffe, 2000). Van Dooren et al. (2014) explain that “learning a complex skill like designing is a continuous process of doing and making explicit. It is about acquiring habits and patterns that are mostly implicitly used by an expert designer” (p. 55).

Tacit knowledge is often procedural, intuitive, and embodied in personal experience (Schindler, 2015; Uluoglu, 2000; Wong & Radcliffe, 2000). Polanyi's (1966) well-known phrase "We can know more than we can tell" (p. 4) encapsulates the central issue. Design educators, who are frequently practitioners themselves, are often challenged by conveying tacit knowledge explicitly to students (van Dooren et al., 2014; Venkatesh & Ma, 2019). Venkatesh and Ma (2021a) assert that within design education, "tutors lack a structured approach to share their tacit knowledge" (p. 1). Likewise, design students face challenges in “knowing” how to design, a skill described as “complex, personal, creative, and open-ended” (van Dooren et al., 2014, p. 54).

Researchers agree that tacit knowledge is built through experience and in design education is acquired through hands-on practice, learning-by-doing (Schön, 1983, 1987) observing, dialogical learning and engaging in the process of action and reflection (Crowther, 2013; McLain, 2022; Shreeve et al., 2010). Given that students are only at the start of their learning journey to become “competent practitioners [who] usually know more than they can say” (Schön, 1983, p. 8), they often struggle with the largely implicit and intuitive nature of tacit knowledge acquisition (van Dooren et al., 2014; Venkatesh & Ma, 2019). Van Dooren et al. (2014) explain this challenging process “As a student you learn by doing and by becoming aware of how to do it. The learning process arises from largely implicit knowing and acting, includes making explicit and becoming aware, and results again in largely implicit knowing and acting” (p. 55).

Despite challenges in tacit knowledge communication, the design studio is recognized as a key site for tacit knowledge acquisition (Venkatesh & Ma, 2021a). Various formal and informal learning opportunities such as demonstrations, hands-on tutor feedback, critiques and social interactions, including peer learning opportunities, make the studio a place of learning and social engagement (Crowther, 2013; Shreeve, 2011). Peer interaction and peer learning are recognised as key to creating a community of practice (Wenger, 1998) which emphasises the role of social interaction and participation in tacit knowledge sharing and construction (Venkatesh & Ma, 2021a, b).

Various conceptual frameworks for tacit knowledge construction in design education have been proposed (e.g., van Dooren et al., 2014; Venkatesh & Ma, 2021b), and there is ongoing debate regarding which elements of design are “learnable” and “teachable” (Buckley et al., 2021). Despite this debate, the pedagogical foundations of design have remained largely unchanged over the years. However, the rapid advancement of online technologies in design education, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, has created new opportunities for tacit knowledge acquisition. Researchers such as Günay and Coskun (2023), Venkatesh (2021), and Fleischmann (2021b) observed the emergence of an alternative studio pedagogy, blending physical design studios with online technology. Venkatesh (2021) sees opportunities in the context of tacit knowledge construction: “a blended learning studio stimulates creativity and enhances the acquisition of tacit knowledge through newer forms of understanding and discussions” (Venkatesh, 2021, p. 14).

Design learning in the critique

Despite the implicit nature of designing, explicit awareness of the design process is essential in teaching and learning (van Dooren et al., 2014). This involves bringing unconscious actions and decisions to conscious awareness, enabling learners to understand the underlying principles and reasoning behind their actions. However, as van Kampen (2019) observed, students “when asked to talk about their intentions, beginning design students tend to focus on what they did and how they did it, instead of why they did it and how it influenced their work” (p. 36). This struggle to articulate their intentions and the underlying reasons behind their design decisions is often witnessed during a ‘critique’.

The critique is seen as an opportunity to generate tacit knowledge through evaluation and articulation of feedback (Venkatesh & Ma, 2021a). The critique can take many forms. As Hokanson (2012) explains, formal critiques are structured events–sometimes public–and are summative and evaluative in their assessment nature. Desk critiques or quick pinups of work are informal critiques. That is when students share ideas and progress of their project with an educator/tutor who provides feedback and guides the students as mentor in their creative development (Pradel et al., 2015). The formal critique is usually applied as the primary assessment method to evaluate students’ work and their ability to communicate design ideas and articulate their creative process (Blair, 2006; McCarthy, 2011; Schrand & Eliason, 2012).

Researchers have identified the critique, whether in a group situation, one-to-one or peer-to-peer, as a foundation for learning in design education. McLaren (2017) observes: “Common to all models is the dialogical process which reveals alternative perspectives. This is considered central for any reflective practice as it creates a dynamic process, motivates professional learning through enquiry and deepens critique” (p. 181). Spendlove (2017) calls the critique a “dialectic process” that is “inherently creative and design orientated as the process involves resolution and refinement through dialogic enquiry” (p. 75). The outcome of design students’ work is not only the result of individual creative efforts, but also the result of public scrutiny during the critique process. Hokanson (2012) argues: “Any critique develops both the critic and designer” (p. 79).

Design learning is essentially a process of self-discovery, shaped by ongoing dialogue between students and educators, among peers, and formalised in the critique. This critique process is meant to encourage students to develop their creativity, sharpen thought processes and refine their technique (Ellmers, 2006; Lee, 2006; McLaren, 2017). The critique as transfer of tacit knowledge (Brosens et al., 2023) provides a structured opportunity for students to articulate their design decisions, receive feedback from peers and tutors, and reflect on their own work. Through this process, students can develop a deeper understanding of the underlying principles and practices of design (Gray, 2019).

The educational value of the critique is contentious and has been questioned over the years. Day (2013) describes the critique as “gladiatorial, combative and unforgiving, with few places to hide, and yet we expect students to prosper and survive this with little instruction” (p. 9). While research revealed that some design students experience the critique “as ‘supportive’, ‘helpful,’ and ‘nurturing’… suggesting an overall communicative environment characterized by collaboration” (Dannels et al., 2011, p. 104), others may experience the critique as stressful and anxiety-provoking, which can impact on student learning (Day, 2013; McCarthy, 2011; Pradel et al., 2015). Stress can lead to misinterpretation of feedback and feedback can be forgotten by the time students have left critique sessions (Healy, 2016; McCarthy, 2011).

Furthermore, the educator is often at the centre of feedback sessions. Some researchers claim that the critique can become teacher-focused (e.g., Healy, 2016) and empowers the design educator as the final authority, rather than encouraging students to question designs and appraise their own designs through critical thinking (Blythman et al., 2007; Healy, 2016; McCarthy, 2011). Dannels et al. (2011) also observed that design students often receive conflicting feedback, which can be confusing and leave them uncertain about what to focus on when developing their ideas/project further.

The technology-enhanced critique

Even pre-pandemic, some researchers argued that design educators need to take advantage of technology to enhance teaching and learning in design education (e.g., Healy, 2016). The use of internet technology as part of the critique process can facilitate peer feedback and peer assessment which has the potential to make design students more active participants during the critique (Gray, 2019) and hence “places the student at the center of the knowledge construction processes” (Venkatesh, 2021, p. 123). Fleischmann (2016) argues that peer assessment is a more effective way to approach the critique in larger classrooms. Yorgancıoğlu (2020) suggests that “peer critique methods have the potential for students to develop as active agents of assessment processes by removing the student from being a subject of assessment” (p. 11).

Design educators have utilized online technology for peer critique in various design domains. For instance, Wauck et al. (2017) surveyed 127 UI design students from three North American universities who engaged in small assessment groups and shared project prototypes online, resulting in perceived higher quality feedback emphasizing on process. Similarly, Jones (2014) discusses the use of Compendium DS software to facilitate visual interaction and assessment among students online, leading to significantly valuable dialogue for student learning.

The shift to online design classrooms during the Covid-19 pandemic prompted educators to adapt studio-based critiques for online settings. While some faced challenges in providing individual feedback online (Fleischmann, 2022), others explored cloud-based collaboration tools like Miro, Collaborate Ultra, and Slack for project sharing and feedback (Fleischmann 2022; Lee et al., 2020; Spruce et al., 2021). This transition was a revelation for some educators because they could simultaneously access students’ projects and provide more inclusive feedback (Fleischmann, 2022, 2023).

Course design for the empirical study

What follows is a detailed approach that can be tested by design educators interested in employing an online peer critique process to encourage the process of making tacit knowledge explicit.

The technology-enhanced critique process using formal and informal peer feedback was implemented in the second year “Design and Entrepreneurship” course of the Visual Communication Design major in the Bachelor of Design programme. This course focuses on the graphic aspects of visual communication design to provide an expansive and critical understanding of this discipline and its social context. It includes several strategies for solving visual design problems both logically and intuitively.

The course is divided into a one-hour lecture and a two-hour tutorial. This course had 161 design students enrolled and was taught entirely online in seven tutorials by three tutors over 12 weeks. Each tutorial had between 21 and 26 students. The author of the present research was the course convenor overseeing the management of the course.

The course assessment consisted of a combination of informal and formal peer critiques involving design students within the same tutorial, and formal assessments by the tutor. Table 1 overviews the critiquing format, technology used and timeline of the course.

All peer critiques (formal and informal) were done on cloud-based online platforms (Collaborate Ultra, SurveyMonkey, Google Docs) that facilitated simultaneous multi-user access. These platforms are not specifically designed as assessment tools. Other cloud-based platforms would be equally suitable. The presentations in the virtual classroom via screen sharing and subsequent use of peer feedback platforms were adapted to create a collaborative space where students could share ideas and learn from the creative processes of others. An additional benefit of using these platforms was that students had access to the digital records after the critique (Figs. 1 and 2).

Students were briefed starting in week 3 about how to give constructive feedback and were encouraged to always provide reasons for their feedback. To help students in this process, the “I like/I wish” approach, a strategy used in design thinking to test prototypes, was introduced in week 7. Students were asked to comment using the following structure: “I like … write two things you like about the brand strategy and design and why” and “I wish … write one thing that could perhaps be improved and suggest how you think it could be improved”.

The formal peer assessment rubric, which was used in week 9 and accounted for 15% of the overall course assessment mark, was explained a week before it was used.

Research methods of the empirical study

This study explores student experiences using technology-enhanced formal and informal peer critiques. The research investigates to what extent peer critiquing mediated in an online environment can help design students understand and apply tacit knowledge of design processes. A pragmatic research paradigm underpinned this study which prioritises actionable knowledge, acknowledges the interconnected nature of experience and the underlying principle that knowledge is socially constructed and based on experiences (Kelly & Cordeiro, 2020; Morgan, 2014). Pragmatism enabled the researcher to choose methods that best suit the real nature of the situation (Legg & Hookway, 2020; Morgan, 2014; Punch, 2009). Hence, an online survey was developed using the online survey platform SurveyMonkey and implemented in week 12 at the end of the course. This approach was thought to be the most suitable research method to collect feedback from this large student cohort in a timely manner (Wright, 2005).

To maintain a high level of transparency and allow other researchers to replicate the study effectively (Buckley et al., 2022) the criteria of this qualitative study are detailed as follow: educational activity (see previous section), sampling, management of power imbalances between researcher and participants, interaction with participants, the positionality of the researcher within the research process, and data saturation point.

Sampling and managing power imbalance

A purposive sample tied to the researcher’s objectives was used (Palys, 2008), which enabled the development of targeted questions. Invitations to participate in this research were extended to second-year undergraduate visual communication design students, totalling 161 participants in this course. Most of the students in their second year of study are between 20 and 25 years old. 80% were domestic Australian students and 20% were international students. 90 students completed the survey, a response rate of 56%.

The author was aware that the “very nature of a teacher-researcher’s insider position may bring the risk of subjectivity and bias” (Punch, 2009, p. 44). Faced with the prospect of bias, the author adopted an impartial and objective stance in their approach to the research situation. This was essential for attaining credible and valid results. Hence, the author decided not to teach tutorials, but act as a distanced observer of the situation as course convenor.

Further considering roles and power imbalance (Buckley et al., 2022), tutors were advised to clearly explain to students that participation is voluntary, that the survey is anonymous and cannot be traced back. Informed consent from all participants was obtained ensuring participants understood the purpose of the research and the right to withdraw at any time without consequence (Ethic GU Ref No: 2020/256).

Survey design

The online survey consisted of 19 closed and open questions, 12 of which are relevant to this research. The other questions focused on exploring the students’ expectations around future course offerings and are not presented here. The survey started with two introductory questions to encourage students to freely express their views on their online learning experiences, which could include reflection on the peer feedback experience: “Tell us what you liked about the online class and why.” and “Tell us what you did not like about the online class and why.” Three input fields (reason 1, reason 2, reason 3) were given for both questions to encourage students to reflect in depth. These introductory questions yielded 211 comments on the “like” and 150 comments on the “not like” choices. The comments relevant to this study were extracted and analysed.

The introductory questions were followed by the same question design, starting with a closed question (quantitative data) specifically designed to get an overview of the students’ experience, for example on peer feedback/peer assessment: “You presented your assessment to your peers and received peer feedback. You also evaluated other students’ work. How did you like this form of assessment?” Possible answers: “I did like it.” / “I did not like it.” / “I did not participate.” This closed question was followed by an open question (qualitative data) inviting students to elaborate on their experience and to give a more detailed explanation for their answer choice: “Why did you like this form of assessment or not like it? Please explain your answer.” The remaining questions followed the same question design and are presented in the findings section. Comments on these open questions ranged between 60 and 74 responses with 21 to 121 words.

The author tested the survey questions with a research assistant unfamiliar with design studio education. There were two reasons for this approach: First, the survey results could be improved by eliminating or changing poorly worded or unclear questions (Campanelli, 2008). Secondly, potential question bias can be identified and suggestive questions that could affect the results should be eliminated. Tutors were provided with the link to the survey and asked to conduct the survey in their last tutorial after the students’ presentations had been completed. The survey was anonymous to encourage participants to be honest in their replies (Gray & Malins, 2004).

Data analysis

The general approach to data analysis was inductive with the overall aim of exploration and discovery by examining patterns from the data (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019; Morse & Niehaus, 2009). The quantitative data was used to see an overall trend in the experience of students as a guiding overview. For the analysis of the quantitative data obtained through the survey, the survey tool delivers basic statistical data, including the total number of responses, frequency of individual responses and the percentages. The qualitative data was analysed following inductive reasoning which involves drawing general conclusions or patterns from specific observations (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). The qualitative data obtained through open questions in the survey were analysed using a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Naeem, et al., 2023), which is an “appropriate method of analysis for seeking to understand experiences, thoughts, or behaviors across a data set” (Kiger & Varpio, 2020, p. 1). Thematic analysis is a valuable technique for identifying and interpreting patterns or themes within a dataset (Naeem et al., 2023) and for exploring the different perspectives of the participants highlighting similarities, differences and potential unexpected insights (Braun & Clarke, 2006; King, 2004).

The qualitative data were analysed using NVivo, a research analysis software. The coding process began with first-order coding, also known as topic coding, which involved categorizing the data into predetermined labels such as benefits, challenges, and limitations of peer feedback (Hahn, 2008; Punch, 2009). Second-order coding, or analytic coding (Hahn, 2008), delved deeper into the content of the data, capturing what was happening and what was being said (e.g., “It was good to talk it out with others and share ideas … It helps you see things from the viewpoint of others.”). This process was applied for each data set/data collection event (one tutorial = one data collection event).

Second-order coding, which involves advancing to higher-level categories, focused on identifying patterns, themes, or relationships that emerged from the initial coding phase within each data set. This stage entails synthesising codes into themes to gain deeper insights into the data (Gioia, 2021; Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). Each data set was then compared to identify similarities and potential differences. Second-order coding also entails connecting emerging themes with relevant theory and literature. As described by Gioia et al. (2013), this process involves "cycling between emergent data, themes, concepts, and dimensions and the relevant literature, not only to see whether what we are finding has precedents, but also whether we have discovered new concepts" (p. 21). Throughout this coding process, the researcher remained open-minded to identify connections between codes.

Given the ongoing debates on how to define saturation in qualitative research (e.g., Lowe et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2018), the author retrospectively evaluated 'thematic saturation' (Green & Thorogood, 2014) within the fully analysed and fixed-size dataset (Guest et al., 2020). Thematic saturation was reached after analysing five data collection events. The analysis of the remaining two data collection events did not reveal new issues or themes (Green & Thorogood, 2014) but strengthened previous results. This is likely attributed to the structured nature of the data collection process, the participants were relatively homogeneous and recruited from a specific setting, while the coding process primarily addressed obvious meanings (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Presentation of the data

To present an overview of the students’ experiences, the quantitative data is presented first. Thereafter, the emerging coding categories are presented as headlines and the themes are described. Students’ verbatim quotes are used to illustrate emerging themes, provide explanations and offer insights (Corden & Sainsbury, 2006). Verbatims are also chosen for controlling subjectivity and bias allowing the reader to form “their own judgements about the fairness and accuracy of the analysis” (Corden & Sainsbury, 2006, p. 12).

Limitation of this study

Although the intervention was trialled in seven different tutorials, the participants were part of one cohort with similar conditions (e.g., second year design students studying from home). It should be noted that 44% of the enrolled students did not participate in this research and hence their views on the researched phenomena are unknown. When undertaking this survey, the researcher did not apply statistical analysis. This decision was based on the limitation of the sample size as well as the predominantly qualitative nature of this research.

While this study suggests that online critique can lead to positive learning outcomes, it is important to acknowledge that these outcomes are not solely attributable to the online critique method itself. Rather, they were influenced by the careful and thoughtful pedagogical approach integrated into this study (see Course Design). It is important to recognise that the observed outcomes are a result of both the online critique method and the underlying pedagogy.

It is not within the scope of this research to analyse the relative merits of internet platforms with design education applications.

Findings

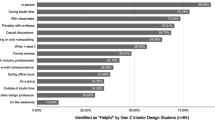

The closed survey questions presented in Table 2 give an overview of students’ perception on engaging with online peer critique and indicate that students generally support the informal and formal online peer critique.

A total of 265 student comments were received, detailing the reasons for the above responses. These comments, presented in the following sections, have been grouped thematically to reflect overarching survey trends, starting with the experienced challenges.

Student challenges with the online peer critique

Students were not unanimous in their acceptance of online peer critique. Of the students surveyed, 19% “did not like” the peer feedback process. The reasons given in the 15 comments were varied, with no unifying theme. One student expressed concerns about the intimidating aspect of the experience:

“I felt this style of peer feedback was a little confronting as the whole class saw what everyone thought.”

Another student wished for more critical feedback:

“It was great to receive a lot of positive feedback. However, I don't think it was as critical as it could have been if the teacher were to provide feedback instead.”

Two students remarked that peers can “play favourites” in their assessments, while another pointed out the technology impediments: “Much slower and harder to communicate.” Another observed that there was a lack of "tone of voice" when reading the comments, which could lead to misunderstandings.

Two students did not trust peer grading. One was uncomfortable with the grading rubric and felt that the assessments should be done by a teacher, while another questioned the honesty of the peer grading process.

Despite criticisms of online peer critique, students expressed strong support for the informal and formal online peer critique processes, as outlined below.

Student benefits with the online peer critique

Visualisation and record of the design process and feedback

The design students experienced the online peer critique and feedback sessions as explicit, verbal signposts for their evolving designs. This written reference encourages the development of reflective practice. Students elucidated the advantages of digitally archived peer critique in the comments below:

“For me, receiving feedback in the virtual classroom was different because I was able to remember and take in more feedback during the virtual classroom than during face-to-face classes. I would be too nervous and shaken to remember what anybody has said about my presentation.”

“I had all my feedback typed down ... In face-to-face it is talked about and used as discussion and I can't record and/or take notes as I would be in the middle of presenting, leaving me to remember accurately all the feedback and pray I didn't get anything mixed up.”

“I was able to go back and see my peers’ comments even after the sessions were finished. I could easily look back and take on the feedback…. And I could also make sure I was on the same track as other people.”

The online community of practice

The informal and formal peer critique also developed a digital community of practice because students shared the same learning/exploration process in the group feedback sessions. The feedback was also more readily accepted and valued because it came from fellow students and seemed more authentic. This mitigated fears that often arise in studio critiques, where the design teacher or tutor is the ultimate arbiter of success. The following comments from the students reflect this sense of empathy and bonding, which has been an essential component of the informal feedback process in the physical studio:

“I felt my peers gave great feedback, almost better than teachers in some cases, as they had been going through the same design process and understood better.”

“It felt easier to share feedback this way and receive it as well. It just feels less embarrassing as a whole. Seeing a list of feedback and nice comments was just really heart-warming and validating to my creative process.”

“I really liked this as it gave students a chance to see a lot of different views and opinions on your work which was helpful when it came to changing/refining things. It also helped build bonds with the students and was quite fun to participate in and help others.”

This shared experience resulted in the majority of students feeling more engaged in the course as well. Looking at others’ design work and creative process on a regular basis led to students being inspired and more motivated, which can lead to more self-directed learning, as one student describes:

“It was good to see because it gave me a good idea about whether I was on track or not, it mostly inspired me to do more work.”

Making tacit knowledge explicit through shared observations

The survey results indicate that design process requirements also became clearer. 96% of the design students gained a critical perspective from regularly observing the work of their peers throughout the design development process. This understanding of design concepts was achieved by comparing individual work in the context of the group’s multiple perspectives, as the following comments show:

“I love seeing other people's work. It's always interesting to see how other creatives respond differently to me to the same task. A couple of the projects I absolutely loved watching the formation and thought the finished outcomes were fantastic. I also thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to provide feedback and/or appreciate the work my peers had done. It's great to be involved throughout the whole process because you feel invested in the finished product. At the same time, it's also encouraging to see projects not as refined as your own in order to reassure yourself you are doing ok in the course.”

“I think this is a really valuable exercise, gives you an opportunity to compare how you're progressing with the group, and we often were able to solve problems or share solutions for common problems and issues (together). Even getting some advice from what other people were experiencing that helps you to prevent the same issues in your own work.”

“It was great. Not only does it inspire you to push and meet the achievement level of your peers but it also can help you understand how to approach tasks if you happened to be struggling”

Having the opportunity to receive feedback from multiple sources also made students rethink some of their designs, as the following comments illustrates:

“Having peer feedback helped see how many people had the same feedback and what really needed to be changed or what was really good.”

“I actually found the week 3 voting most valuable because I had my heart set on a completely different product range, which no-one else ended up voting for. It was an eye-opener about what appeals to other people.”

Anonymity as an advantage

Many students commented on the advantage of presenting from home and providing feedback anonymously:

“I felt less scared to share online compared to in class, online gave me more confidence.”

“It felt easier to present from home as I was in a comfortable space.”

“The feedback was more honest because it is anonymous and hence more helpful.”

“It was easier receiving feedback behind a computer then in front of a classroom full of people.”

The online peer feedback and peer assessment allowed shyer students to fully engage in the critique process:

“I have received more feedback in virtual classrooms than face-to-face. Many people may be shy when they are face-to-face.”

“People are more likely to speak up and voice their opinion in a virtual classroom.”

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore benefits and challenges of informal and formal peer critiques in an online learning environment in making tacit knowledge explicit. Overall, 96% of students gained valuable experience by seeing the work of their peers throughout the design developing process. This study highlights multiple reasons why informal and formal online peer critiques were perceived by students as beneficial to their learning rather than intimidating:

-

creation of a community of practice where ideas were shared in a collaborative way,

-

greater emotional confidence in giving and receiving feedback,

-

willingness to adopt criticism and apply it to individual design projects,

-

digital record of the design process and feedback for students to refer back to,

-

development of reflective and engaged practice by students.

In the following, the experienced benefits are discussed in context of making tacit knowledge explicit and fostering tacit knowledge acquisition through the affordances of the online learning environment.

Tacit knowledge construction

The critique process in design education is meant to encourage students to develop their skills and creativity and to engage in learning that develops their reflective practice (Ellmers, 2006; Fleischmann, 2016; Lee, 2006). These aspects were achieved by informal and formal online peer critiques in this cohort. Contributing to the positive attitude of the majority of students (72%) towards online peer critique, and a resulting openness to take on suggestions for change, was receiving feedback from multiple sources within tutorials of 20 or more students. The value of receiving feedback from multiple perspectives in a peer environment has been explored (Fleischmann, 2016, Gray, 2019; Smith, 2020) and is thought to be central to reflective practice (McLaren, 2017) and to contribute to refining tacit knowledge in the design learning environment (Venkatesh & Ma, 2021a). In this cohort, peer feedback helped students to be more open and to implement suggestions, as this student described: “Hearing other perspectives and takes on my process helped me get better in certain aspects. It felt very open and group-oriented instead of just individual personal feedback.” As reported, 77% of design students changed their work based on peer feedback. Students who did not, had presented design solutions that worked already. This exchange of intuitive insights in a collaborative environment and multi-source feedback is argued to connect tacit knowledge with the explicit aspects of design (Venkatesh & Ma, 2021a). The evaluation and articulation of feedback and access to multiple perspectives helped students 'become more aware' of their tacit knowledge by encouraging them to reflect on their experiences and extract implicit insights and understanding as discussed by van Dooren et al. (2014), van Kampen (2019), and Venkatesh and Ma, 2021a.

This shared experience resulted in most students feeling more engaged in the course. Students felt part of an online community of practice (Wenger, 1998) because students shared the same learning and exploration process in the group feedback sessions (“my peers… had been going through the same design process and understood better”). There was a sense of understanding, clarity, or validation regarding their design decisions and direction. Students could benchmark their own work against the work of their peers. This is what van Kampen (2019) describes as “moments of resonance” when students recognise parallels between the work and process of their peers and their own (“This…gives you an opportunity to compare … share solutions for common problems and issues (together)”). These moments of resonance are often seen as pivotal for learning and the development of tacit knowledge, as they provide opportunities for students to internalise and integrate feedback, refine their understanding, and enhance their design capabilities.

According to various design educators, the social interaction that is crucial for transforming tacit knowledge into explicit practice is missing in the online environment because it does not support causal observations, ad hoc interactions and informal communication (Fleischmann, 2022; Tessier & Aubry-Boyer, 2021). However, this was not the case for the cohort in this study. As mentioned previously, design students felt part of a group (community of practice) sharing the same experiences in observing and participating in design processes unfolding and making design principles and approaches explicit in this shared environment. This led to an openness in receiving feedback, being engaged and motivated by others, and broadening their understanding of the design process through their own and others' experiences (“Not only does it inspire you to push and meet the achievement level of your peers but it also can help you understand how to approach tasks”). Similar observations were made by Spruce et al. (2021) when they engaged students in a collaborative cloud-based learning experience where “students’ learning journeys [were] visible, shared and explicit [which helped] to create communities with shared understandings, approaches, and skills” (p. 105). The design process contextual feedback from multiple perspectives also highlighted problems that a design educator might have overlooked if giving one-to-one feedback because the number of students needing feedback was so large.

Structure and online affordances

It's worth emphasizing that the outcomes observed among students can also be attributed to the meticulously planned and systematic approach to peer critique implemented in this study. Through a combination of both formal and informal peer feedback mechanisms spanning the complete project period, an environment conducive to trust and mutual support was fostered among the students. This enabled students to actively participate in and observe the entire design journey, from its initial stages to refinement and eventual completion. By emphasizing the iterative nature of design rather than focusing solely on the project outcome in a singular event, students gained a deeper understanding of the design process and the cognitive aspects involved (van Dooren et al., 2014).

The simultaneous access to multi-source feedback enabled through cloud-based platforms allowed students to both access and provide feedback simultaneously. Suggestions for improvement in a design idea/solution were validated from the students' point of view by the multitude of student opinions. This finding was previously reported by Fleischmann (2016). In a physical critique environment, gathering such multitude of insights (allowing everyone to contribute) within the limited timeframe of a typical critique would be impossible. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that tapping into the tacit knowledge of individuals and sharing within an online community can create possibilities for situated learning (Oztok, 2013).

Another beneficial aspect of online peer critiques is the anonymity they offer. As Day (2013) observed that the traditional studio critique setting may not adequately support students who find it challenging to participate publicly, a sentiment echoed by Blair (2006), who noted that shy individuals may struggle to express themselves in front of a large audience. Some researchers argue that online environments and anonymous peer feedback can create a safer space for individuals to share their insights and experiences, leading to knowledge exchange, and increase participation levels, which can be conducive to tacit knowledge sharing and construction (Noroozi & Wever, 2023). Feedback such as “I felt less scared”, “It felt easier … as I was in a comfortable space”, and “It was easier receiving feedback behind a computer then in front of a classroom full of people” support these views. Anonymity can sometimes reduce social barriers and power differentials (Panadero & Alqassab, 2019) encouraging more open and honest communication as was the case in this study (“The feedback was more honest because it is anonymous and hence more helpful”).

But a few students found it challenging to receive feedback from their peers and would have preferred a teacher-focused approach, as peer feedback was not perceived as critical or honest enough. The shift from the teacher as the central figure of the critique to a more democratic process where more perspectives were recorded suited the majority but not all students. These findings align with some design educators who support this shift in authority to a more decentralised model (e.g., Fleischmann, 2016; Wauck et al., 2017; Yorgancıoğlu, 2020).

Feedback records

A key technological advantage of online peer critique is the implementation of digitally archived peer comments (suggestions for improvement or solutions that work well) that students can revisit to reflect and respond to after the critique is completed. Venkatesh (2021) describes this as “collaboratively created knowledge” which “can be transformed into readily available and time-stamped knowledge artifacts” (p. 134). Many design educators who have criticised the physical studio critique (e.g., Day, 2013; Pradel et al., 2015) point out that stress can lead to misinterpretation of feedback or that it is forgotten when students leave the critique session (Blair, 2006; Healy, 2016; McCarthy, 2011). This was also reported in this study when students describe their physical studio critique experience which inhibits reflection and resulting internalisation, and thus tacit knowledge construction: “…during face-to-face classes. I would be too nervous and shaken to remember what anybody has said about my presentation.” In contrast, student comments in this study clearly show the contribution of the digital recording to mitigating stress and facilitating internalisation through reflection: “I was able to go back and see my peers’ comments even after the sessions were finished. … and take on the feedback”.

The digital recording of collaboratively created knowledge during the critique process seems to have been crucial in helping students transform difficult-to-grasp tacit knowledge (such as intuition, understanding of aesthetics) (Venkatesh & Ma, 2019) into accessible and reusable information. Having the opportunity to revisit these comments gives students time to think, reflect, and internalise feedback, fostering the development of a reflective practice, as advocated by Schön (1987), which is considered essential for tacit knowledge development in design.

Conclusion

Design educators are sometimes challenged by making tacit knowledge explicit, which through its nature of being procedural, intuitive, and embodied in personal experience, is often difficult to articulate. For students, tacit knowledge acquisition can be difficult given that learning emerges from primarily implicit understanding and action, encompassing the act of rendering implicit knowledge explicit and fostering awareness. This conversion of tacit understanding of the design process into a concrete understanding of design principles is the foundation of studio pedagogy and its key assessment tool–the critique.

The critique’s role is to foster students' creativity, think critically, reason, understand concepts, and process information effectively through a give-and-take dialog which can be intimidating to some students. But as this study demonstrates, the online peer critique, with its sharing potential, can overcome difficulties experienced in the physical studio critique.

Through sharing and critiquing work in a virtual environment, students accessed and translated tacit knowledge into action. Witnessing the design process, changes and achievements periodically in a shared environment helped students accept and absorb feedback. This process of sharing and critiquing work not only fostered a sense of community but also nurtured reflective practice and engaged learning.

Moreover, the online platform afforded several advantages for tacit knowledge acquisition. The anonymity provided a safer space for students to share their insights and experiences, leading to more open and honest communication. Access to digital records facilitated reflection on feedback post-critique. This allowed students to revisit and reflect on peer comments, enhancing their understanding and internalisation of tacit knowledge.

The structured approach to online peer critique played a pivotal role in guiding students through the iterative design process and fostering a deeper understanding of design principles and approaches. By emphasising multi-source feedback and creating opportunities for reflection, the online environment facilitated the transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit practice.

Overall, students found the process supportive, inclusive, and instrumental in benchmarking and refining their work. It also fostered confidence in their creative abilities and appreciation for diverse approaches to problem-solving in design. While some students faced challenges with peer assessment, the educator's role in ensuring fairness and consistency remains vital.

Nonetheless, technology-enhanced peer critiques prove beneficial in fully online courses and warrants exploration in physical design studios as more programs transition to blended learning. These findings mark significant progress in leveraging design critique for tacit knowledge construction in design education and contribute to the evolving discourse on design pedagogy and the role of technology in facilitating learning and knowledge exchange.

References

Blair, B. (2006). At the end of a huge crit in the summer, it was “crap” – I’d worked really hard but all she said was “fine” and I was gutted. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 5(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1386/adch.5.2.83/1

Blythman, M., Orr, S., & Blair, B. (2007). Critiquing the Crit. Retrieved 25 July, 2022 from www.academia.edu/586074/Critiquing_the_Crit

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Brosens, L., Raes, A., Octavia, J. R., & Emmanouil, M. (2023). How future proof is design education? A systematic review. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 33, 663–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09743-4

Buckley, J., Adams, L., Aribilola, I., Arshad, I., Azeem, M., Bracken, L., . . . Zhang, L. (2022). An assessment of the transparency of contemporary technology education research employing interview‑based methodologies. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32 McLaren, 1963–1982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-021-09695-1

Buckley, J., Seery, N., Gumaelius, L., Canty, D., Doyle, A., & Pears, A. (2021). Framing the constructive alignment of design within technology subjects in general education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 31, 867–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-020-09585-y

Campanelli, P. (2008). Testing Survey Questions. In J. H. Edith D. de Leeuw, Don Dillman (Eds.), International Handbook of Survey Methodology (1st ed., pp. 176 - 200). Routledge.

Charters, M., & Murphy, C. (2021). Taking art school online in response to COVID 19: From rapid response to realising potential. The International Journal of Art and Design Education (iJADE), 49(4), 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12384

Corden, A., & Sainsbury, R. (2006). Using verbatim quotations in reporting qualitative social research: researchers’ views. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/pdf/verbquotresearch.pdf

Crowther, P. (2013). Understanding the signature pedagogy of the design studio and the opportunities for its technological enhancement. Journal of Learning Design, 6(3), 18–28.

Dannels, D. P., Housley Gaffney, A. L., & Martin, K. N. (2011). Students’ Talk about the Climate of Feedback Interventions in the Critique. Communication Education, 60(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2010.487111

Day, P. (2013). The art group crit. How do you make a firing squad less scary? Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 5, 1–15.

Diefenthaler, A. (2021). Design and the US-American education system. In iF Design Foundation (Ed.), Designing Design Education - Whitebook on the of Design Education (pp. 163 - 176). avedition

Ellmers, G. (2006). Reflection and Graphic Design Pedagogy: Developing a Reflective Framework to Enhance Learning in a Graphic Design Tertiary Environment. Paper presented at the ACUADS 2006, Monash University, School of Art, Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne, Victoria. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://ro.uow.edu.au/creartspapers/8/

Filimowicz, M. A., & Tzankova, V. K. (2017). Creative making, large lectures, and social media: Breaking with tradition in art and design education. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 16(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022214552197

Fleischmann, K. (2016). Peer assessment: A learning opportunity for students in the creative arts. In C. Nygaard, Branch, John and Bartholomew, Paul (Ed.), Assessing Learning in Higher Education (pp. 45–58). Libri Publishing.

Fleischmann, K. (2021a). Hands-on versus virtual: Reshaping the design classroom with blended learning. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 20(1), 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022220906393

Fleischmann, K. (2021b). Is the design studio dead? - An international perspective on the changing shape of the physical studio across design domains. Design and Technology Education: an International Journal, 26(4), 112–129. https://openjournals.ljmu.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1169. Accessed 31 May 2024

Fleischmann, K. (2022). A paradigm shift in studio pedagogy during pandemic times: An international perspective on challenges and opportunities teaching design online. Journal of Design, Business & Society, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1386/dbs_00042_1

Fleischmann, K. (2023). German Design Educators' Post-Covid Challenges: Online, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Government Data Restrictions. Design and Technology Education: An International Journal 28(1), 135–153. https://openjournals.ljmu.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1176. Accessed 31 May 2024

Gioia, D. (2021). A Systematic methodology for doing qualitative research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320982715

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

Gray, C., & Malins, J. (2004). Visualizing research - a guide to the research process in art and design. Routlegde - Taylor and Francis Group.

Gray, C. M. (2019). Democratizing assessment practices through multimodal critique in the design classroom. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 29, 929–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-018-9471-2

Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2014). Qualitative methods for health research (Third Edition). SAGE Publications.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE, 15(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Günay, A., & Coskun, A. (2023) Realising a hybrid design studio in basic design, in Derek Jones, Naz Borekci, Violeta Clemente, James Corazzo, Nicole Lotz, Liv Merete Nielsen, Lesley-Ann Noel (eds.), The 7th International Conference for Design Education Researchers, 29 November - 1 December 2023, London, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.21606/drslxd.2024.080

Hahn, C. (2008). Doing Qualitative Research Using Your Computer: A Practical Guide. SAGE Publications.

Hart, J., Zamenopoulos, T., & Garner, S. (2011). The learningscape of a virtual design atelier. Compass: The Journal of Learning and Teaching at the University of Greenwich, (3), 1–15. https://journals.gre.ac.uk/index.php/compass/article/view/45. Accessed 31 May 2024

Healy, J. (2016). The components of the "Crit" in art and design education. Irish Journal of Academic Practice, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.21427/D7RB1V

Hokanson, B. (2012). The Design Critique as a Model for Distributed Learning. In L. Moller & J. B. Huett (Eds.), The Next Generation of Distance Education (pp. 71–84). Springer Science+Business Media.

Jones, D. & Lotz, N. (2021). Design education: Teaching in crisis. Design and Technology Education: An International Journal, 26(4):4–9. https://openjournals.ljmu.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1160. Accessed 31 May 2024

Jones, D. (2014). Reading students’ minds: Design assessment in distance education. Journal of Learning Design, 7(1), 27–39.

Kelly, L. M., & Cordeiro, M. (2020). Three principles of pragmatism for research on organizational processes. Methodological Innovations, 13(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799120937242

Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

King, N. (2004). Chapter 21: Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280119.n21

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development (First Edition). Prentice Hall.

Lee, T., Pham, K., Crosby, A., & Peterson, F. (2020). Digital collaboration in design education: how online collaborative software changes the practices and places of learning. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2020.1714700

Lee, N. (2006). Design as a learning cycle: A conversational experience. Studies in Learning, Evaluation Innovation and Development, 3(2), 12–22.

Legg, C., & Hookway, C. (2020). Pragmatism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (Summer 2021 Edition). Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://plato.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=pragmatism

Linneberg, M. S., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: a synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012

Lowe, A., Norris, A. C., Farris, A. J., & Babbage, D. R. (2018). Quantifying Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Data Analysis. Field Methods, 30(3), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X17749386

McCarthy, C. (2011). Redesigning the Design Crit. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://ako.ac.nz/assets/Knowledge-centre/RHPF-c40-Redesigning-the-design-crit/RESEARCH-REPORT-Redesigning-the-Design-Crit.pdf

McLain, M. (2022). Towards a signature pedagogy for design and technology education: A literature review. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32, 1629–1648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-021-09667-5

McLaren, S. V. (2017). Critiquing Teaching: Developing Critique Through Critical Reflection and Reflexive Practice. In P. J. Williams & K. Stables (Eds.), Critique in Design and Technology Education (pp. 173–192). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3106-9

Morgan, D. L. (2014). Pragmatism as a Paradigm for Social Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(8), 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413513733

Morse, J. M., & Niehaus, L. (2009). Mixed method design: principles and procedures (First Edition). Routledge - Taylor and Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315424538

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231205789

Noroozi, O., & Wever, B. D. (Eds.). (2023). The Power of Peer Learning - Fostering Students’ Learning Processes and Outcomes: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29411-2

Oztok, M. (2013). Tacit knowledge in online learning: Community, identity, and social capital. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 22(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2012.720414

Palys, T. (2008). Purposive Sampling. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (Vol. 2, pp. 697–698), Sage.

Panadero, E., & Alqassab, M. (2019). An empirical review of anonymity effects in peer assessment, peer feedback, peer review, peer evaluation and peer grading. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1253–1278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1600186

Polanyi, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Chicago Press.

Pradel, P., Sun, X., Oro, B., & Nan, W. (2015). A preliminary comparison of desk and panel crit settings in the design studio, In G. Bingham, D. Southee, J. McCardle, A. Kovacevic, E. Bohemia & B. Parkinson (Eds), Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, (pp. 544–549), Loughborough, UK. The Design Society. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://www.designsociety.org/publication/38500/A+PRELIMINARY+COMPARISON+OF+DESK+AND+PANEL+CRIT+SETTINGS+IN+THE+DESIGN+STUDIO

Punch, K. (2009). Introduction to research methods in education. Sage.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., . . . Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity - International Journal of Methodology, 52, 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Scagnetti, G. (2017). A dialogical model for studio critiques in Design Education. The Design Journal, 20(Sup1), S781–S791. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1353024

Schindler, J. (2015). Expertise and Tacit Knowledge in Artistic and Design Processes: Results of an Ethnographic Study. Journal of Research Practice, 11(2), 1–22.

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. Jossey-Bass.

Schrand, T., & Eliason, J. (2012). Feedback practices and signature pedagogies: What can the liberal arts learn from the design critique? Teaching in Higher Education, 17(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.59097787

Selçuk, M. Ö., Detand, J., & Emmanouil, M. (2021). Challenges in multidisciplinary student collaboration: Reflections on student peer assessments in design education. Paper presented at the LearnXDesign 2021, Shandong University of Art and Design, Jinan, China.

Shreeve, A. (2011, 18–19 May 2011). The Way We Were? Signature pedagogies under threat. Paper presented at the Researching Design Education: 1st International Symposium for Design Education Researchers; CUMULUS ASSOCIATION// DRS, Paris, France.

Shreeve, A., Sims, E., & Trowler, P. (2010). “A kind of exchange”: Learning from art and design teaching. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(2), 125–138.

Smith, C. (2020). When students become critics: Reviewing peer reviews in theory and practice. Charrette, 6(1, Spring ), 71–92. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/12873/

Son, K., Choi, D., Kim, T. S., & Kim, J. (2024). Demystifying tacit knowledge in graphic design: Characteristics, instances, approaches, and guidelines. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06252, 1–18. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://arxiv.org/pdf/2403.06252v1

Spendlove, D. (2017). The Identification and Location of Critical Thinking and Critiquing in Design and Technology Education. In P. J. Williams & K. Stables (Eds.), Critique in Design and Technology Education (pp. 71–86). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3106-9

Spruce, J., Thomas, P., & Moriarty, S. (2021). From sharing screens to sharing spaces. Design and Technology Education: An International Journal, 26(4), 96–111. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://openjournals.ljmu.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1168

Tessier, V. & Aubry-Boyer, M. P. (2021). Turbulence in crit assessment: from the design workshop to online learning. Design and Technology Education: An International Journal 26(4): 86–95. Retrieved 31 May, 2024 from https://openjournals.ljmu.ac.uk/DATE/article/view/1167

Uluoglu, B. (2000). Design knowledge communicated in studio critiques. Design Studies, 21(1), 33–58.

van Dooren, E., Boshuizen, E., Merriënboer, J. V., Asselbergs, T., & Dorst, M. V. (2014). Making explicit in design education: generic elements in the design process. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 24, 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-013-9246-8

van Kampen, S. (2019). An Investigation into Uncovering and Understanding Tacit Knowledge in a First-Year Design Studio Environment. International Journal of Art and Design Education (iJade), 38(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12171

Venkatesh, A. (2021). Facilitating Tacit Knowledge Construction: Re-Examining Boundaries of the Design Studio Environment. CUBIC JOURNAL. 4, Pedagogy · Critique · Transformation), 122— 127. https://doi.org/10.31182/cubic.2021.4.043

Venkatesh, A., & Ma, H. (2019). Tacit Learning in an Extended Interior Design Studio. Paper presented at the DRS LearnXDesign, METU, Ankara.

Venkatesh, A., & Ma, H. (2021a). Critical conversations as a tool for students’ tacit knowledge construction: An interpretive research in interior design studio interactions. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 2, 1–10.

Venkatesh, A., & Ma, H. (2021b). Tacit Knowledge Construction in Studio-based Learning: A Conceptual Framework. The International Journal of Design Education, 16(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-128X/CGP

Wauck, H., Yen, Y.-C., Fu, W.-T., Gerber, E., Dow, S. P., & Bailey, B. P. (2017). From in the Class or in the Wild? Peers Provide Better Design Feedback Than External Crowds. Paper presented at the CHI '17: Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA. May 06–11 retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025477

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Wong, W. L. P., & Radcliffe, D. F. (2000). The Tacit Nature of Design Knowledge. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 12(4), 493–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/713698497

Wright, K. B. (2005). ‘Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services’, Journal of Computer-Mediated. Communication, 10, 1–31.

Yorgancıoğlu, D. (2020). Critical reflections on the surface, pedagogical and epistemological features of the design studio under the “New Normal” conditions. Journal of Design Studio, 2(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.46474/jds.744577

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I, Katja Fleischmann, declare that I have no conflicts of interest related to this research article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fleischmann, K. Making tacit knowledge explicit: the case for online peer feedback in the studio critique. Int J Technol Des Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-024-09911-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-024-09911-8