Abstract

In the growing literature on the importance of household balance sheets to macroeconomic developments, the relationship between housing wealth and fiscal outturns needs consideration given the likely links between housing market developments and particular tax headings. We adopt the housing net worth model for this purpose. Using a panel dataset of 18 European countries over the period 1998 to 2017, we find changes in housing net worth having a significant impact on the primary budget balance, with increases (decreases) in housing net worth causing the budget balance to improve (dis-improve). Further support for the importance of this channel to the public finances arises by differentiating observations based on the amount of revenue raised under particular tax headings.

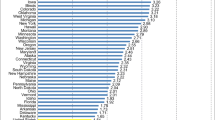

Source: OECD. See https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RS_GBL for more details

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

By reference to financial liberation in Finland in the late 1980s, Oikarinen (2009) notes the tight connection between house prices and household borrowing and how greater availability of credit likely leads to a higher demand for housing, while house prices can influence household borrowing through various wealth effects. Such interaction can exacerbate boom–bust cycles and raise the fragility of the banking sector.

Household net worth, as a percentage of net disposable income, is sourced from https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-net-worth.htm.

The General Government primary budget balance and output gap (mentioned below) data are both sourced from the EU AMECO database.

Those eighteen countries are Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden. The panel of data is unbalanced as there are not observations for all countries between 1998 and 2017. Further specifics on the data sample are included in the appendix.

F-tests of the joint significance of the fixed effects are reported at the bottom of each column. The p-values reported in the tables strongly reject the null hypothesis that the cross-sectional effects are redundant throughout.

Being a dynamic panel model, the Arellano–Bover/Blundell–Bond model already has a lagged dependent variable in the specification.

We use these tax revenues as a percentage of GDP as a proxy for the particular tax rates that arise in each country for each relevant tax heading.

The regressions in Table 4 were also estimated by weighted least squares with no material differences in the results arising.

High-tax observations are predominantly associated with western European countries rather than central or European countries, pointing to the HNW channel being more influential on budget outturns in ‘old’ Europe.

References

Addison-Smyth, D., & McQuinn, K. (2010). Quantifying revenue windfalls from the Irish housing market. Economic and Social Review, 41(2), 201–223.

Addison-Smyth, D., & McQuinn, K. (2016). Assessing the sustainable nature of housing-related taxation receipts: The case of Ireland. Journal of European Real Estate Research, 9(2), 193–214.

Agnello, L., Castro, V., & Sousa, R. (2012). How does fiscal policy react to wealth composition and asset prices? Journal of Macroeconomics, 34(3), 874–890.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 29–51.

Beltratti, A., & Morana, C. (2010). International house prices and macroeconomic fluctuations. Journal of Banking and Finance, 34, 533–545.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 115–143.

Cerutti, E. M., Dagher, J., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2017). Housing finance and real-estate booms: A cross-country perspective. Journal of Housing Economics, 38, 1–13.

Cheng, I.-H., Raina, S., & Xiong, W. (2014). Wall street and the housing bubble. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2797–2829.

Cronin, D., & McQuinn, K. (2021). Consumption and housing net worth: Cross-country evidence. Economics Letters, 209, 110140.

De Bondt, G., Gieseck, A., & M. Tujula (2020). Household wealth and consumption in the euro area. ECB Economic Bulletin, 1/2020.

Dell’Ariccia, G., Ebrahimy, E., Igan, D., & Puy, D. (2020). Discerning good from bad credit booms: The role of construction. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/20/02, Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Eschenbach, F., & Schuknecht, L. (2002). Asset prices and fiscal balances. ECB Working Paper 141, Frankfurt-am-Main: European Central Bank.

Favara, G., & Imbs, J. (2015). Credit supply and the price of housing. American Economic Review, 105(3), 958–992.

Goodhart, C., & Hofmann, B. (2008). House prices, money, credit and the macroeconomy. European Central Bank Working Paper 888, Frankfurt-am-Main: European Central Bank.

Larch, M., & Turrini, A. (2010). The cyclically-adjusted budget balance in EU fiscal policymaking. Intereconomics, 45(1), 48–60.

Le Leslé, V. (2012). Bank debt in Europe: Are funding models broken? IMF Working Paper, 2012/299, Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Leamer, E. E. (2010). Tantalus on the road to Asymptotia. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(2), 31–46.

Liu, E.X., Mattina, T., & Poghosyan, T. (2015). Correcting "beyond the cycle:' accounting for asset prices in structural fiscal balances. IMF Working Paper 2015/109, Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

McCarthy, Y., & McQuinn, K. (2017). Price expectations, distressed mortgage markets and the housing wealth effect. Real Estate Economics, 45(2), 478–513.

McQuinn, K. (2017). Irish house prices: Deja vu all over again? Special article, Quarterly Economic Commentary, Winter, The Economic and Social Research Institute.

Mian, A., Rao, K., & Sufi, A. (2013). Household balance sheets, consumption and the economic slump. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1687–1726.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2014). What explains the 2007–2009 drop in employment? Econometrica, 82(6), 2197–2223.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2017). Household debt and business cycles worldwide. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), 1755–1817.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2018). Finance and business cycles: The credit-driven household demand channel. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32(3), 31–58.

Morris, R., & Schucknecht, L. (2007). Structural balances and revenue windfalls: The role of asset prices. ECB Working Paper 737, Frankfurt-am-Main: European Central Bank.

Oikarinen, E. (2009). Interaction between housing prices and household borrowing: The Finnish case. Journal of Banking and Finance, 33, 589–774.

OECD (2020). Revenue statistics 2020: Tax revenue trends in the OECD. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/revenue-statistics-highlights-brochure.pdf

Price, R., & Dang, T.T. (2011). Adjusting fiscal balances for asset price cycles. OECD Working Paper 868, Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Economics Department.

Price, R., Dang, T.T., & Guillemette, Y. (2014). New tax and expenditure elasticity estimates for EU budget surveillance. OECD Working Paper 1174, Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Economics Department.

Romano, J., & Wolf, M. (2017). Resurrecting weighted least squares. Journal of Econometrics, 197(1), 1–19.

Tagkalakis, A. (2011a). Asset price volatility and government revenue. Economic Modelling, 28(6), 2532–2543.

Tagkalakis, A. (2011b). Fiscal policy and financial market movements. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35, 231–251.

Tsatsaronis, K., & Zhu, H. (2004). What drives housing price dynamics: Cross-country evidence. Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, March, 65–78.

Tujula, M., & Wolswijk, G. (2007). Budget balances in OECD countries: What makes them change? Empirica, 34, 1–14.

Wolswijk, G. (2010). Fiscal aspects of housing in Europe. In P. Arestis, P. Mooslechner, & K. Wagner (Eds.), Housing market challenges in Europe and the United States (pp. 158–177). Palgrave Macmillan.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank a referee for his/her comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Central Bank of Ireland and Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), respectively. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Central Bank, the ESRI, or the European System of Central Banks.

Appendix: Data coverage

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cronin, D., McQuinn, K. The housing net worth channel and the public finances: evidence from a European country panel. Int Tax Public Finance 30, 1251–1265 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-022-09751-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-022-09751-z