Abstract

An important part of the resistance to higher refugee immigration in rich countries is due to the fear of the negative fiscal consequences. Yet this article shows that the fiscal consequences even of substantially increased refugee immigration are likely to be quite modest. According to the estimates, if the European Union received all refugees currently in Asia and Africa, the implied average annual fiscal cost over the lifetime of these refugees would be at most 0.6% of the union’s GDP. If other rich countries also shared the burden, the cost per country would be even lower.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Disagreement over refugee immigration has paralyzed European policy making for several years. Although it has been strongly prioritized by political leaders of the European Union, and several proposals have been put forward, little actual progress has been made either on border management or on how to distribute or redistribute refugees across member states. At the heart of this policy problem is the strong resistance to refugee immigration among large parts of the population in each country. This resistance appears to be due to two main components: refugee immigration increases cultural heterogeneity, and it may weaken public finances.Footnote 1 While concerns about increased cultural heterogeneity are mostly subjective and value-based, the effects of refugee immigration on public finances can in principle be objectively measured. Such measurement will improve countries’ understanding of the consequences of admitting more or fewer refugees.Footnote 2

In this article, I investigate what would be the likely fiscal consequences if the European Union would allow increased refugee immigration. The analysis uses data from Sweden, which has had high refugee immigration from several countries of origin for several decades, and high-quality data that allow identifying these refugees and tracking their economic performance. The results indicate that the fiscal consequences would be fairly modest even if refugee immigration was substantially increased. As a benchmark, the fiscal redistribution to the entire refugee population in Sweden in 2015 is estimated to have been the equivalent of 1.0% of GDP. If the European Union would resettle every single refugee who currently resides in Asia or Africa, it would amount to an immigration rate of 2.5%. The implied average annual fiscal redistribution to these refugees over their expected lifetime (58 years) is estimated to be the equivalent of approximately 0.6% of GDP, i.e., substantially below the corresponding number for Sweden in 2015. This estimate is based on an assumption about the labor market potential of these hypothetical refugees that is likely to be an exaggeration in the negative direction.

2 Previous literature and motivation

There exists a large literature about the fiscal consequences of immigration. Influential contributions are, among others Smith and Edmonston (1997), Lee and Miller (1998, 2000) and Storesletten (2000). Estimates have been made for a large number of Western countries. Rowthorn (2008) reviews many of these and summarizes the results—quite famously in both academic and non-academic circles—as the net fiscal contribution of the entire immigration population in a country almost always being in the interval between minus 1% and plus 1% of the country’s GDP.

Yet this large literature is not much informative about the consequences of the immigration of refugees. In more or less all countries, the total immigrant stock is dominated by people who immigrated for labor market reasons, i.e., because of their opportunities to find productive work. Hence, they are not much representative of refugees, who have immigrated for completely different reasons, and whose employment rates are on average far below those of other immigrants (Fasani et al. 2018). In Ruist (2015), I provide the first specific estimate of the fiscal net contribution of refugee immigrants. I estimate that in 2007, the Swedish public sector redistributed the equivalent of 1.0% of GDP from the rest of the country’s population to its accumulated refugee population, including those who immigrated as family members of refugees.

This result gives a sense of orders of magnitude. In 2007, Sweden had been the Western country with the highest refugee immigration per capita over the previous more than 2 decades, and the refugee population amounted to 5% of the country’s total population. Hence, the result implies that at (by the time) record levels of refugee immigration, the fiscal consequences may be described as clearly noticeable, yet also clearly manageable.

However, this estimate does not provide much more than orders of magnitude. It does not provide what would be the measure of primary political interest, i.e., an evaluation of the fiscal consequences of receiving a certain number of refugees today. The reason for the discrepancy is that the total Swedish refugee population in 2007, like total refugee populations all over Europe today, was strongly skewed with respect to three variables that are of first-hand importance in determining the estimated fiscal redistributions. First, the population was young, with few individuals above 65 years of age, and hence low costs related to old age. Second, it was on average quite newly arrived. Hence, its employment rates would be projected to rise substantially in future years. Finally, its composition across countries of origin was very different from that of current European refugee inflows. It was quite strongly dominated by refugees from Former Yugoslavia. These have, for more than 2 decades, performed substantially better on the Swedish labor market than almost all other refugee groups (Ruist 2018). It is thus likely that today’s refugee inflows, which have a different composition across countries of origin, may have more negative fiscal consequences.

Hence, although it is possible to transform the results in Ruist (2015) to an estimate of the fiscal redistribution to the average refugee in 2007, it is difficult to assess to what extent this average is representative of what we would really want to know, which is the corresponding average over the lifetime of a refugee who immigrates today. We do not know to what extent the latter average will be more positive, because the population studied in Ruist (2015) had on average had little time for labor market integration. We do not know to what extent the latter will be more negative, because so few of those studied in Ruist (2015) had reached retirement age. And we do not know to what extent it will be different in some direction—presumably the negative—because today’s refugees are differently distributed across countries of origin compared to the population studied in Ruist (2015).

The aim of the present study is therefore to provide a more direct assessment of the fiscal implications of higher or lower current refugee immigration, through an analysis that explicitly takes these three variables into account. I use data from Sweden in 2015 to calculate fiscal net contributions of refugee immigrants, depending on their age, years since arrival, and country of origin. I then use these conditional values to forecast future net contributions over the lifetime of refugees who arrive today. The results thus represent (above estimation error) what future net contributions will be, under the assumption that the conditional values calculated for 2015 remain stable. This amounts to making the most of the available data, and should be unambiguously more informative than the estimated net contribution of a total population in a given year. True future outcomes are of course likely to differ in either direction, depending on refugees’ future labor market success.

3 Swedish refugee immigration and refugees’ labor market performance

Sweden became a prominent destination for refugee migration in the early 1980s. Since then, the country’s share of all European refugee immigration has far exceeded its share of the total European population. In the decade before the refugee crisis in 2015, i.e., in 2005–2014, Swedish refugee immigration per capita was a full ten times as high as that in the rest of the European Union (data source: Eurostat). By the end of 2017, slightly more than 8% of the resident Swedish population had once immigrated as refugees or family members of refugees (Ruist 2018).

Like more or less all migration flows worldwide, Swedish refugee immigration has always been concentrated in the younger working ages. With this age distribution, immigration would be unambiguously beneficial to public finances, if the immigrants were on average similar to the rest of the population conditional on age. The immigrants were not present in the country during their first twenty living years, during which net contributions to public finances are negative. Instead they arrive in the beginning of their productive working life.

However, if an immigrant group’s labor market performance is weak enough compared with that of other similarly aged residents, its immigration does not have to have a positive impact on public finances. In Sweden, as in the rest of Europe (Fasani et al. 2018), refugees’ labor market performance has for long been considerably weaker than that of natives and of migrants who immigrated for primarily economic reasons. Average annual incomes of refugees who immigrated in 1982–2014, measured in percent of the median income of 20–50-year-old native men in each year, by sex, arrival period, and years since arrival, are shown in Fig. 1. There is some variation between cohorts, which to a large extent correlates with fluctuations in aggregate unemployment (very low in the 1980s, very high in the early 1990s, in between thereafter). Typically, average income is very low in the first few years after immigration. It reaches above 60% of the reference income after 4–10 years for men, and 11–14 years for women. It flattens out at slightly below 80% for men, and around 70% for women. It is thus not surprising that the fiscal consequences of refugee immigration have been found negative, in spite of refugees’ concentration in younger working ages.

Refugees’ average income by sex, immigration period and years since immigration. Notes: Data are from Statistics Sweden’s Linda database, years 1983–2015. The sample includes refugees (from 1990 excluding those who immigrated as family members) who were 20–50 years old when immigrating. Average income is measured in percent of the median income of 20–50-year-old native men in the same year. Separate curves are shown for separate immigration periods

Around the averages shown in Fig. 1, there is a quite striking amount of variation in each cohort between refugees of different countries of origin. Those from certain countries have persistently performed better than others. One example is shown in Fig. 2, which shows similar information as Fig. 1, yet only for the cohort that arrived in 1997–2001. Separate curves are shown for eight main countries or groups of countries of origin. For about the first 10 years in Sweden, the average income of refugees from Former Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, or Eritrea, is at least twice as high as that of refugees from Somalia. As I show in detail in Ruist (2018) (including the online appendix), the pattern of which groups have performed more strongly and more weakly on the labor market, has been mostly stable over the entire period 1983–2015. Yet it is difficult to find a convincing explanation for the pattern. Differences in formal education do, e.g., not appear to play a major role.

Refugees’ average income by sex, country of origin and years since immigration. Notes: Data are from Statistics Sweden’s Linda database, years 1998–2015. The sample includes refugees (from 1990 excluding those who immigrated as family members) who were 20–50 years old when immigrating. Average income is measured in percent of the median income of 20–50-year-old native men in the same year. Separate curves are shown for separate countries of origin

Figures 1 and 2 thus show that there is large variation in refugees’ labor market performance, depending on the number of years that have passed since their immigration, and on their country of origin. They thus illustrate that taking these two factors into account will improve the measurement of the fiscal impact of refugee immigration.

4 Method

This study follows in a long tradition of studies of the fiscal net contributions of immigrant groups in a fairly large number of Western countries. Conceptually, a large part of fiscal revenues and costs can be ascribed to certain individuals or groups of individuals. Taxes are paid, and transfers are received, by individuals. Schools are there for the children who attend them, and so on.

It is thus conceptually possible to think of such a thing as an individual’s net contribution to public finances. This contribution would be the sum of all taxes and fees paid by the individual, minus the transfers they receive, and some version of the share of public spending on public goods that may reasonably be attributed to them. For example, the cost of running a school could conceptually be seen as split equally between the children who attend it. Certain costs would then most appropriately be split equally across the entire population, e.g., those for infrastructure and defense.

With good enough data, these fiscal net contributions could also be calculated. We would not be interested in calculating them at the individual level, but doing this for larger groups of people may be informative about how demographic changes may impact on fiscal strength. For example, knowledge of what average contributions are in different age brackets is useful for predicting the impact of a changing age structure, such as the increasing share of elderly that is projected to happen over the next decades in virtually all Western countries. And knowledge about how net contributions of certain immigrant groups differ from those in the total population helps calculating the impact of more or less of the corresponding types of immigration.

This type of calculation is the objective of the present study. However, it has an important margin of error. While we may quite accurately calculate the fiscal net contribution of an immigrant group, this is not actually the measure of interest. The policy-relevant object of interest is instead the fiscal effect of the presence of the immigrant group, i.e., whether allowing the group to immigrate has strengthened or weakened public finances, and to what extent.

For several reasons, the fiscal net contribution and the fiscal effect are unlikely to be fully equivalent. The reason is that as immigrants enter an economy, they also affect other agents of that economy. For example, if an immigrant obtains employment, earns income, and pays income tax, this amounts to a fiscal revenue. If this job was created because the immigrant arrived, this fiscal revenue also equals the effect of the immigrant’s arrival on total income tax revenue. Yet on the other hand, if the job would have existed also if the immigrant never arrived, and would then have been done by someone who is now unemployed, because the immigrant took the job, the effect of the immigrant’s presence on total income tax revenue is instead zero. In this case, the immigrant’s fiscal contribution becomes a positively biased estimate of the fiscal effect of their presence in the country.

Other mechanisms may instead lead the same estimate to be negatively biased. For example, there may exist economies of scale in the provision of certain public goods. If a country’s population increases by 1% due to immigration, all public goods spending does not necessarily increase by fully 1%. Possibly expenses on things such as roads and infrastructure may increase by less.

These two are the most commonly cited reasons why the fiscal net contribution is unlikely to equal the fiscal effect, but several others have also been discussed (Smith and Edmonston 1997; Lee and Miller 1998, 2000; Rowthorn 2008; Preston 2014). In sum, it is difficult to assess whether the true fiscal effect of the presence of a group is more positive or more negative than the group’s fiscal net contribution. And the answer may be different for different groups.

The majority of studies in the literature deals with this problem by simply estimating the fiscal net contribution, and trusting this to be at least a fair proxy for the effect of interest (see reviews by Rowthorn 2008; Preston 2014). A minority take the alternative approach of attempting to explicitly model the most important dynamic mechanisms that create the difference between the net contribution and the effect (e.g., Storesletten 2000; Lee and Miller 1998, 2000; Hansen et al. 2017). The obvious weakness of this strategy is that there are many candidate mechanisms, and the exact form is not well known for any of them. Hence, the outcomes of this modeling may differ hugely depending on which assumptions are made. This in turn also implies that researchers have considerable scope to influence the outcomes of the exercise, through their choices of what to model and how to model it.Footnote 3 An important advantage of the simpler and more common strategy is that it is transparent enough to enable readers to assess which factors are actually the most important in driving the results of the calculations. For these reasons, this study follows the majority of the literature, and the explicit recommendation of Rowthorn’s (2008) influential review, in not attempting to explicitly incorporate these general or partial equilibrium effects into the analysis.

4.1 Measuring fiscal net contributions

I measure fiscal net contributions using data from Statistics Sweden’s Linda database for 2015. The database collects information from various public sources for a random sample of 3% of the Swedish total population, and a supplement sample of 20% of the foreign-born population (for details about the database, see Edin and Fredriksson 2000). Hence together, these two samples comprise approximately 22.4% of the foreign-born population. A small number of individuals reportedly residing in households with no disposable income are excluded from the analysis, as they are most likely not present in the country.

For foreign-born residents, the database includes information on the reason for immigration, hence allowing those who immigrated as refugees or family members of refugees to be identified. However, for those who immigrated before 1990, this variable has poor coverage. Hence, I also classify as refugees all immigrants who either immigrated from Hungary or Romania in any year before 1990, or from Afghanistan, Chile, Ethiopia, Lebanon, Somalia, or Syria in 1975–1989. The resulting total refugee population in 2015 consists of 690,000 individuals, or 7.0% of the total Swedish population.

Fiscal net contributions of refugees are estimated by identifying, to the extent possible in the data, from which individuals different public revenues originate, and to which individuals public costs are targeted. Conceptually, a large majority of public revenues, and also a substantial part of costs, may be ascribed to certain individuals or groups of individuals. On the revenue side, this is true for income taxes, payroll taxes, property taxes, and consumption taxes. On the cost side, it is true for direct transfers, as well as the costs of welfare services such as schools and hospitals. For many of these items, the data also allow the individual source or target to be identified. In other cases, known statistical relations at the group level may be applied. Finally, the calculations ascribe parts of revenues and costs equally across all individuals in the country. This is partly where identifying an individual source or receiver is conceptually possible, yet not so in the data. But it is also because substantial shares of public costs, such as defense, infrastructure, international aid, and central administration, are most reasonably viewed as being targeted to all residents of the country to the same extent.

In more detail, the analysis ascribes public revenues and costs across the population as follows:

Income and property taxes, and transfers These are directly observed at the individual level.

Payroll taxes Payroll taxes are paid by the employer as a percentage of the employee’s wage. Different percentages apply, depending on the age of the worker. Payroll taxes cannot be directly observed in the data. Hence, they are calculated as the individual’s labor income multiplied by the relevant age-dependent payroll tax rate. Finally, as these calculations do not give exact results, all values are scaled to make total payments correspond to those reported in the government’s annual fiscal report.

Consumption taxes Consumption taxes are dominated by VAT, but also include taxes on goods such as alcohol, tobacco, and pollutants. They cannot be observed in the data. Yet Statistics Sweden estimated the aggregate relation between household income and consumption taxes paid in 2009, calculating the average share of household income spent on consumption taxes in each income decile. These shares are applied in the analysis. Finally, as these calculations do not give exact results, all values are scaled to make total payments correspond to those reported in the government’s annual fiscal report.

Corporate taxes Corporate taxes are conceptually difficult to ascribe to certain individuals. There are different possible ways to treat them in the analysis. They could, e.g., be distributed equally across the population, or proportionally to labor income, or to capital income. It is difficult to argue that either of these is the correct one. In the present study, I ascribe them proportionally to labor income, as a rough measure of a person’s contribution to economic activity in the country.Footnote 4

Public consumption Average public consumption in the areas of child care, education, health, social assistance, and culture/leisure cannot be observed in the data. Yet they have been estimated by Statistics Sweden for 2013 by age, gender, and seven groups of countries of origin. These values are applied in the analysis, after being multiplied by a markup of 5% to account for nominal cost inflation in the provision of these services. (Nominal inflation in service provision costs per capita between 2013 and 2015 can be studied for many different items in the Swedish Association of Municipalities and Regions’ Kolada database. Most values hover around 5%.)

Crime and justice Following Ruist (2015), and the sources mentioned therein, public spending on crime and justice is assumed to be 2.5 times as high per capita for refugees as for the rest of the population.

Labor market policy Following Ruist (2015), and the sources mentioned therein, public spending on labor market programs—apart from those specifically targeted to newly arrived refugees (which are included in the next item)—is assumed to be twice as high per capita for refugees as for the rest of the population.

Integration policy These costs are mainly incurred during a refugee’s first time in Sweden. They are evenly distributed across all refugees who immigrated in 2013–2015.

All other public revenues and costs, including the public sector’s total surplus in 2015, are distributed equally across the total population.

4.2 Forecasting future contributions

Ideally, to forecast future fiscal net contributions of refugees who arrive today, taking age, years since arrival, and country of origin into account, refugees’ net contributions would first be calculated, according to the details given above, for all possible combinations of these three variables. Together with predicted age-specific mortality rates, these values could then be applied to forecast future net contributions of a current refugee inflow with any distribution over the three variables.

In other words, e.g., a refugee who arrives from Iraq in 2015, at the age of 23, would be expected to have a fiscal net contribution in the year 2020 that is equal to what the average contribution was in 2015 among those who were 28 years old in that year and had immigrated from Iraq at age 23. The forecasts would thus represent what future net contributions will factually be, under the assumption that, conditional on age, years since immigration, and country of origin, future average contributions will remain unchanged compared to 2015.

Due to Sweden’s 3-decade-long history of fairly high refugee immigration, and to the large high-quality data set, what the data permit is not so far from this ideal case. However, the number of observations in the resulting three-dimensional matrix becomes fairly small or even nonexistent for certain combinations of variable values. This is mostly because relatively few refugees have been in the country for more than 30 years, or are above 65 years of age. It is also because refugee immigration from most countries has only been high during limited periods of time. Hence, some aggregation and assumptions must be made to eliminate any holes in the three-dimensional matrix. Specifically, I do the following three adjustments:

- 1.

Between having spent 30 years in the country, and retiring at the age of 65 (if the latter does not happen first), annual net contributions are assumed not to change over time.

- 2.

Net contributions of refugees who are 65 years old or above are not directly estimated from refugees in the data. They are instead estimated from the corresponding age-specific values in the total population, minus the difference in public pension payments between all natives and all immigrants (11,000 kronor per year).

- 3.

Net contributions are estimated for two groups of countries. The first consists of those countries of origin which, among the major refugee-sending countries, have had the strongest historical labor market performance (Former Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Iran). The second consists of those which have had the weakest (Iraq and Somalia). Together, these two groups then represent an exaggerated interval of possible outcomes for the average refugee. In some periods, the average refugee will be closer to the more positive end of this interval, in other periods to the more negative. But since all inflows tend to be mixed, none of these endpoints is likely to be reached.

When forecasting future net contributions of current refugee immigrants, the age distribution of the current inflow is taken to be that of the combined Swedish 2011–2015 inflow. Age-specific mortality rates are assumed to follow those of the total Swedish population (yet for computational simplicity they are set to zero below fifty, and to one at one hundred years of age). Remigration of refugees is assumed to be zero. Throughout the last decades, remigration rates have been very low for all refugee groups in Sweden.Footnote 5

5 Results

As a benchmark, Table 1 reports cross-sectional results from 2015, i.e., an estimate of the fiscal net contribution of the entire Swedish refugee population, which in that year corresponded to 7.0% of the total population. The first column shows a summary of Swedish public finances in 2015. Revenues and costs were 1794.6 billion kronor each (with the aggregate fiscal surplus included among “Other” costs). The vast majority of revenues were income (and property), payroll, and consumption taxes. Important costs were public pensions and the costs of the education and health systems. Yet the single largest item on the cost side is “Other.” This to a large extent reflects the large share of public costs that are considered targeting the country’s entire population to the same extent.

The second column shows for each item the amount that is ascribed as originating from or targeting refugees. It shows that refugees contributed 92.0 billion in revenues, but were the target of 133.5 billion in costs. The difference at the bottom line is thus a net public cost of 41.5 billion kronor for this entire refugee population, which quite exactly equals 1.0% of Swedish GDP in the same year. The last two columns assist the understanding of which items drive this total net cost. The third column shows “counterfactual” refugee values. This implies what the corresponding number would have been, if refugees had been similar to the total population. In other words, it is simply the values in the first column multiplied by refugees’ population share of 7.0%. Finally, the last column shows the difference between the second and third columns. Hence, it shows how much larger or smaller a factual value is compared with the counterfactual.

The last column thus shows that refugees’ negative fiscal net contribution in 2015 is mostly created on the revenue side. Of the total deficit of 41.5 billion kronor, about four-fifths, or 33.7 billion, are due to revenues per capita being lower for refugees, and only one-fifth is due to costs per capita being higher. Differently put, refugees make up 7.0% of the population, contribute 5.1% of the revenues, and are the target of 7.4% of the costs. Hence, the total deficit is mostly a direct consequence of refugees’ low employment rates (and, less importantly, lower average incomes for those who are employed).

On the cost side, there are large differences between different cost items. Since few refugees are old, they are strongly underrepresented as recipients of public pensions and “social costs,” which are primarily for elderly care. On the other hand, they are the sole targets of the “integration” and “refugees’ introduction benefits” costs. They are also strongly overrepresented as receivers of social assistance and housing allowances, where they receive almost half the total amounts.

5.1 Forecasts

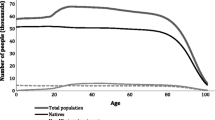

The forecasted annual fiscal net contributions of the average refugee who immigrates today, which are the actual purpose of this study, are shown in Fig. 3 by years since immigration. Separate curves are shown for those from the countries with the strongest and weakest historical labor market performance. Both curves show large deficits in the first few years after immigration. In these years, as we have seen, average income and hence tax payments are very low. Large sums are also spent on integration programs aiming at building up the labor market skills of the newly arrived. As these are phased out and employment rates start climbing in the following years, the net deficit decreases rapidly. The group with the strongest performance reaches zero after about 15 years. A period of about 25 years follows, where the average net contribution of this group is positive. After about 40 years in the country, as more refugees reach retirement age, the net contribution becomes negative again. Finally, it approaches zero as the numbers of years since immigration approaches one hundred and fewer are still alive.

Refugees’ average fiscal net contributions per capita by years since immigration. Notes: “Strongest” refers to refugees from the countries of origin with the strongest historical labor market performance (Former Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Iran). “Weakest” refers to those with the historically weakest performance (Somalia, Iraq)

For the group with the weakest historical performance, the period of positive average net contributions is basically absent. The group’s curve only touches zero from below, after around 20–30 years in the country, before again becoming more negative. Yet it is immediately clear from the figure, that also for the strongest group, the positive contributions after 15–40 years in the country are much too small to balance the negative contributions of the earlier and later years. In other words, also these refugees do not pay for their own costs over their lifetimes.

Refugees who arrive today are on average quite young. Their estimated remaining lifetime in Sweden on arrival is 58.3 years. Over this period, the average yearly fiscal net contribution is estimated at − 53,000 kronor per year for the group with the strongest historical labor market performance, and − 94,000 kronor per year for the group with the weakest. By comparison, Swedish GDP per capita in 2015 was approximately 430,000 kronor, and public sector revenues per capita were 180,000 kronor. The interval between these two groups should be interpreted as a wide interval of possible outcomes for the average refugee in a cohort, since refugee immigrants in a period have never belonged exclusively to either of these two groups. Another point of comparison is the net contribution of the average refugee in the country in 2015, which according to the calculations was − 60,000 kronor. This value is thus within the interval, but much closer to its less negative number.

These forecasted values may be somewhat exaggerated in the negative direction though, if we take into account that the structure of the fiscal sector might need to change in the future. Swedish public finances are comparatively strong, and the last 2 decades have seen gradually falling public debt. Also, in contrast to what is the case in several other European countries, a substantial share of the aging of the population due to large post-WWII baby boom cohorts has already happened in Sweden (the baby boom started earlier in Sweden, which was not directly involved in the war). However, some aging of the population still remains, and it is likely that this will imply that the average revenues/costs ratio conditional on age will need to increase in the future.

This may be done in many different ways, and hence it is difficult to assess how it will affect the numbers calculated here. But to give a sense of the magnitudes involved, I have also used the same method to forecast the average annual fiscal net contribution over the lifetime of a native person that is born today. The result was an annual net contribution of − 17,000 kronor. Hence, it is possibly more appropriate to make a rough correction by subtracting this number from the − 53,000 and − 94,000 kronor that were reported for the two refugee groups.

6 Discussion: the fiscal cost of solving the problem

The numbers reported here may be used to provide an estimate of the fiscal cost of increased refugee immigration in Europe. The structure of the fiscal sector is different in different European countries, implying that the Swedish case is not fully representative. Quite possibly, refugees’ labor market performance may also differ between countries, but there exist no data that enable a good assessment of this. Yet the challenge of refugees having low employment rates and high probabilities of needing public financial support appears to be present all over Europe (Fasani et al. 2018), and it is quite likely that the Swedish case at least provides a reasonable order of magnitudes of what the corresponding fiscal net costs per refugee are also in other countries.

In June 2018, the UNHCR reported that the number of refugees (not counting Palestinians) in need of assistance in Asia and Africa was 13 million. This corresponds to 2.5% of the population of the EU. To most likely err on the negative side of truth, I assume that if all these refugees would be received in Europe, they would perform like the group with the weakest historical labor market performance in the analysis that has been presented in this paper.Footnote 6 The average annual fiscal net cost over the lifetime of members of this group that was reported in the previous section corresponded to 22% of Swedish GDP per capita. Multiplying this share with an immigration rate of 2.5%, the average annual cost of receiving all these refugees would be approximately 0.6% of GDP in the European Union.

In other words, if the EU would receive the entire—record-high—current stock of international refugees in Asia and Africa, the implied average annual fiscal cost over these refugees’ average lifetime would be only slightly above half of Sweden’s fiscal net cost for its 2015 refugee population. If other rich countries also shared the burden, the cost would be even lower. This average over 58 years obscures much variation though. Figure 3 shows that the net cost was considerably higher in the first years after immigration. Yet the Swedish example provides relevant information also about peak costs. The hypothetical refugee immigration volume of 2.5% of the population of the EU corresponds almost exactly to the combined Swedish refugee immigration (including family members) per capita in the 4 years 2014–2017. According to Fig. 3, the fiscally most costly years relating to this record-high inflow should be the years 2016–2018. In other words, it is most likely that no Western country has ever had a fiscal net cost due to refugee immigration that has been as high as that in Sweden in 2016–2018. Yet in spite of this, Swedish public revenues exceeded costs in each of these years. Without doubt, public finances would have been even stronger in the absence of the high refugee immigration. But the example shows that even at their historical peak, it has been possible to cope with the fiscal costs of refugee immigration without major problems.

Notes

These concerns are consistently referred to in public discussions in different countries, and are the rhetorical focus of political parties that strongly oppose refugee immigration. Much research (e.g. Dustmann and Preston 2007; Card et al. 2012) has shown that similar concerns are important in explaining resistance to immigration in general. These studies also highlight the role of concerns about increased competition on the labor market. Yet this factor is seldom mentioned in public discussions about current European refugee immigration, which is logical when it appears to take the median refugee more than ten years to find employment (Fasani et al. 2018).

As part of this, it may also improve their chances of agreeing on schemes of monetary compensation between them in proportion to refugee volumes. Among others, Schuck (1997) and Fernández-Huertas Moraga and Rapoport (2014) have suggested tradable refugee quotas as a means to achieve an efficient distribution of refugees across countries. Such schemes of market-based setting of the (negative) price of a refugee may be too explicit to be likely to come about in practice (Sandel, 2012; Hatton 2017). Yet the EU already operates minor monetary compensation schemes, without explicit market determination of the compensation levels, and larger ones have been proposed.

In Ruist (2017), I give an example of two different studies of very similar cases of immigration, where the estimated effects differ by a factor of a whopping sixty.

This item represents a fairly small share of public revenues, so how it is treated has a fairly modest effect on the results. The choice made in this study makes the contribution ascribed to refugees fairly low, as their share of total labor income is low. As can be deducted from Table 1 in the results section, the estimated total fiscal revenue from the entire Swedish refugee population in 2015 would have been 1.6% (1.5/92) higher, and the estimated total net fiscal cost of the entire refugee population would have been 3.6% (1.5/41.5) lower if corporate taxes had instead been ascribed equally across the whole population.

An earlier study of remigration of Swedish immigrants is Edin et al. (2000), which reported that 91 percent of those who migrated to Sweden from non-OECD countries 1970–1990, a large share of which were refugees, remained in Sweden five years after immigration. In the larger research project that was reported in Ruist (2018), and of which this study is part, I also investigated—but did not report—remigration rates for all historical refugee groups whose employment assimilation patterns are studied in that report. I found that more—most often much more—than 90 percent of all individuals remained in Sweden 10 years after immigration in all the studied groups, with the sole exception of those who immigrated from Eastern Europe in the 1980s and remigrated after the fall of communist rule in their home countries.

Bevelander (2011) and Ruist (2018) report that refugees who are resettled to Sweden from a third country typically have weaker labor market performance than those who arrived as “spontaneous” asylum seekers. Hence, the historical populations on which the estimates in this paper are based, which are very strongly dominated by spontaneous asylum seekers and their family members, are likely to have undergone some positive selection. However, as shown in Ruist (2018), the differences between these two categories are small in comparison with the large differences between countries of origin.

References

Bevelander, P. (2011). The employment integration of resettled refugees, asylum claimants, and family reunion migrants in Sweden. Refugee Survey Quarterly,30, 22–43.

Card, D., Dustman, C., & Preston, I. (2012). Immigration, wages, and compositional amenities. Journal of the European Economic Association,10, 78–119.

Dustmann, C., & Preston, I. (2007). Racial and economic factors in attitudes to immigration. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 7, Article 62.

Edin, P.-A., & Fredriksson, P. (2000). LINDA—Longitudinal individual data for Sweden. Working paper 2000:19, Department of Economics, Uppsala University.

Edin, P.-A., LaLonde, R., & Åslund, O. (2000). Emigration of immigrants and measures of immigrant assimilation: Evidence from Sweden. Swedish Economic Policy Review,7, 163–204.

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., Minale, L. (2018). (The struggle for) refugee integration into the labour market: Evidence from Europe. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11333.

Fernández-Huertas Moraga, J., & Rapoport, H. (2014). Tradable immigration quotas. Journal of Public Economics,115, 94–108.

Hansen, M. F., Schultz-Nielsen, M. L., & Tranæs, T. (2017). The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type. Journal of Population Economics,30, 925–952.

Hatton, T. (2017). Refugees and asylum seekers, the crisis in Europe and the future of policy. Economic Policy,32, 447–496.

Lee, R., & Miller, T. (1998). The current fiscal impact of immigrants: Beyond the immigrant household. In J. Smith & B. Edmonston (Eds.), The immigration debate. Washington: National Academy Press.

Lee, R., & Miller, T. (2000). Immigration, social security, and broader fiscal impacts. American Economic Review,90, 350–354.

Preston, I. (2014). The effect of immigration on public finances. Economic Journal,124, 569–592.

Rowthorn, R. (2008). The fiscal impact of immigration on the advanced economies. Oxford Review of Economic Policy,24, 560–580.

Ruist, J. (2015). The fiscal cost of refugee immigration: The example of Sweden. Population and Development Review,41, 567–581.

Ruist, J. (2017). The fiscal impact of refugee immigration. Nordic Economic Policy Review,2007, 211–233.

Ruist, J. (2018). Tid för integration. Rapport till Expertgruppen för studier i offentlig ekonomi 2018:3, Swedish government, Ministry of Finance.

Sandel, M. (2012). What money can’t buy: The moral limits of markets. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Schuck, P. (1997). Refugee burden-sharing: a modest proposal. Yale Journal of International Law,22, 243–297.

Smith, J., & Edmonston, B. (1997). The new Americans: economic, demographic and fiscal effects of immigration. Washington: National Academies Press.

Storesletten, K. (2000). Sustaining fiscal policy through immigration. Journal of Political Economy,108, 300–323.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This article is based on research that was financed by the Swedish Ministry of Finance’s Expert Group on Public Economics. I am grateful for comments and suggestions from Moa Bursell, Robert Eriksson, Håkan Hellstrand, Elly-Ann Lindström, Jonas Norlin, Dan-Olof Rooth, Dan Sölverud, Lena Unemo, and Robert Östling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruist, J. The fiscal aspect of the refugee crisis. Int Tax Public Finance 27, 478–492 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09585-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09585-2