Abstract

We apply recently proposed individual welfare measures in the context of preference heterogeneity, derived from structural labour supply models. Contrary to the standard practice of using reference preferences and wages, these measures preserve preference heterogeneity in the normative step of the analysis. They also make the ethical priors, implicit in any interpersonal comparison, more explicit. Information on preference heterogeneity is obtained from a structural discrete choice labour supply model for married women estimated on microdata from the Socio Economic Panel in Germany. We construct welfare orderings of households according to the different metrics, each embodying different ethical choices concerning the treatment of preference heterogeneity in the consumption-leisure space and provide empirical evidence about the sensitivity of the welfare orderings to different normative principles. We also discuss how sensitive the assessment of a tax reform is to the choice of different metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Contrary to what is often thought, a sensitivity analysis does not introduce genuine preference heterogeneity into the normative analysis. In each step of the sensitivity analysis, all individuals or households are endowed with the same preference ordering.

The point is not that the normative tool becomes disconnected from the positive tool(s), since this is the essence of a normative position (see e.g. Creedy and Hérault 2011 or Capéau et al. 2009 for interpretations and applications, based on a similar explicit distinction between the positive and normative step, and Manski (2012) for an explicit plea to distinguish both steps and a critical position as far as current knowledge of consumption-leisure preferences is concerned to inform tax policy).

In our empirical application, we only deal with welfare metrics at the individual level, since our application is restricted to labour supply choices of female spouses in couples with fixed labour supply of the husband. For a similar application for 11 European countries and the US, see Bargain et al. (2013). Conceptually, the welfare metrics can as well be applied to households, either in a unitary setting with one household preference ordering or with two individuals each described by its own preference ordering as is common in the collective household models (see Vermeulen 2002 for an overview, and Bloemen 2010 for a recent application and evaluation in the context of labour supply). For applications of the methodology of this section to aggregate analyses such as ranking countries by means of alternatives to GDP, see Fleurbaey and Gaulier (2009), Jones and Klenow (2010), and for an overview Fleurbaey (2009).

In the empirical application, we will find that this deterministic part of the preferences (captured by observable vector \(\mathbf {z}_{i}\)) explains only part of the variation in choices for individuals facing the same constraints. The rest of the variation is due to ’unexplained heterogeneity’. At this stage, we do not elaborate the normative treatment of this unobserved heterogeneity. This means that we assume that two individuals with the same vector \(\mathbf {z}\) do have the same preferences.

Bundle dominance states that an individual who has more of all commodities cannot be considered worse off than an individual who has less of everything.

We use superscript LF to refer to the “Laissez Faire” description of this metric in Fleurbaey and Maniquet (2006).

In this case, the equivalent set comes close to an implementation of interpersonal comparability in terms of reference bundles (as in Schokkaert et al. 2009). When the indifference curve is sloping upwards at \(l=0\), the tangency point of the equivalent set for a net wage equal to zero, becomes the corner solution. The Rente criterion, therefore, introduces interpersonal comparability by comparing individuals in the counterfactual situation ’as if they do not work’, that is in terms of the reference bundle \((c,0)\).

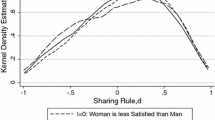

Fleurbaey (2005) gives the example of the metric designed to measure welfare in the multidimensional space of income and health. In that case, it seems natural (though not compelling) that one restricts interpersonal comparisons to the subset of the space where all individuals are healthy (instead of in bad health). And Schokkaert et al. (2009) argue that when constructing a measure of job satisfaction along the lines of subset dominance, one can better restrict interpersonal comparability to the subset of space where all individuals have a good job instead of when they have bad jobs.

Framed in terms of a responsibility-compensation cut, one could say that this criterion holds people maximally responsible for differences in their tastes for leisure and is only willing to eventually compensate differences in (hypothetical) wage rates.

For an overview, see Haan and Steiner (2005).

We choose to focus on married couples since the economic literature e.g. Blundell and McCurdy (1999) has shown that behavioural labour supply responses of married women are particularly important.

To guarantee positive first derivatives with respect to consumption and leisure, transformations of the coefficients might be necessary. But in our empirical application, the first derivatives were found to be positive for all households.

For a detailed description of the SOEP, see Wagner et al. (2007).

The median of the empirical distribution in the following intervals define the discrete points: 0, [0–15], [16–34], [35–40], \(>\) 40. The estimation results are robust to changes in the approximation of the distribution of working hours.

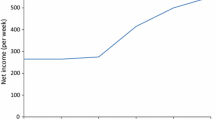

In several papers, e.g. Bargain et al. (2010), the effect of the tax-benefit system on the working incentives are discussed in detail by analysing budget lines for different household types. Given the focus of this paper, which is on the normative analysis, we refer the reader to the previous studies for a detailed account of the translation of the German tax-benefit system into budget constraints.

Estimation results for this wage equation can be obtained by the authors upon request.

We use a parametric bootstrap with 1000 draws from the estimated variance-covariance matrix.

Note that for comparability, we always use expected rather than observed household income.

The positive effect of the East German dummy on net income follows from the fact that we control for non-labour income (i.e. mainly the income of the husband), which is higher for West German households. A regression without this non-labour income as explanatory variable gives the expected negative sign for the East German dummy on net income.

The central idea of this reform was to reduce labour costs and therefore to improve the competitiveness of the German economy. At the same time, VAT was increased from 16 to 19 %. Given that we do not model consumption behaviour of individuals, we are unable to analyse the welfare effects of this second part of the reform.

We find an increase in the expected female participation rate by 0.323 % in a 95 %-confidence interval of [0.29 - 0.357] and an increase in the expected working hours by 1.02 % in a 95 %-confidence interval of [0.95 - 1.108].

References

Aaberge, R., & Colombino, U. (2013). Using a Microeconometric Model of Household Labour Supply to Design Optimal Income Taxes. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(2), 449–475.

Aaberge, R., Colombino, U., & Strøm, S. (2004). Do More Equal Slices Shrink the Cake? An Empirical Investigation of Tax-Transfer Reform Proposals in Italy, Journal of Population Economics, 17(4), 767–785.

Aaberge, R., Dagsvik, J., & Strøm, S. (1995). Labour supply responses and welfare effects of tax reforms. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 97, 635–659.

Auerbach, A. (1985) The Theory of Excess Burden and Optimal Taxation, in Auerbach, A. and Feldstein, M. (eds.) Handbook of Public Economics, Vol. 1, Elsevier Science Publishers, 61–127.

Bargain, O., Caliendo, M., Haan, P., & Orsini, K. (2010). ’Making Work Pay’ in a rationed labour market. Journal of Population Economics, 23(1), 323–351.

Bargain, O., Decoster, A., Dolls, M., Neumann, D., Peichl, A., & Siegloch, S. (2013). Welfare. Labor Supply and Heterogeneous Preferences: Evidence for Europe and the US, Social Choice and Welfare, 41(4), 789–817.

Bloemen, H. (2010). An Empirical Model of Collective Household Labour Supply with Non-Participation. Economic Journal, 120, 183–214.

Blundell, R. and McCurdy T. (1999), Labor Supply: a Review of Alternative Approaches, in: Ashenfelter O. and Card D. (eds.), Handbook of Labour Economics, Vol. 3A., Elsevier Science Publishers.

Blundell, R., & Shephard, A. (2012). Employment. Hours of Work and the Optimal Taxation of Low Income Families, The Review of Economic Studies, 79(2), 481–510.

Boadway, R. (2012). Review of ’A Theory of Fairness and Social Welfare’ by Marc Fleurbaey and François Maniquet. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 517–521.

Boadway, R., & Bruce, N. (1984). Welfare Economics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Capéau, B., Decoster, A., De Swerdt, K. and Orsini, K. (2009), Welfare effects of alternative financing of social security. Calculations for Belgium, in: Zaidi, A., Harding, A. and Williamson, P., New Frontiers in Microsimulation Modelling, Chapter 17, 437–470, Ashgate.

Creedy, J., & Kalb, G. (2005). Discrete Hours Labour Supply Modelling: Specification, Estimation and Simulation. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(5), 697–734.

Creedy, J., & Hérault, N. (2011). Decomposing Inequality and Social Welfare Changes: The Use of Alternative Welfare Metrics. Department of Economics Research Paper Number : University of Melbourne. 1121.

Creedy, J., & Hérault, N. (2012). Welfare-improving income tax reforms: a microsimulation analysis. Oxford Economic Papers, 64(1), 128–150.

Decoster, A. and Haan, P. (2010), Empirical welfare analysis in random utility models of labour supply, IZA Discussion Paper Number 5301.

Donaldson, D. (1992). On the aggregation of money measures of well-being in applied welfare economics. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 17, 88–102.

Eissa, N., Kleven, H., & Kreiner, C. (2008). Evaluation of four tax reforms in the United States: Labor supply and welfare effects for single mothers. Journal of Public Economics, 92(3–4), 795–816.

Fleurbaey, M. (2005). Health, and Fairness. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 7(2), 253–284.

Fleurbaey, M. (2006). Social welfare, priority to the worst-off and the dimensions of individual well-being. In F. Farina & E. Savaglio (Eds.), Inequality and economic integration. London: Routledge.

Fleurbaey, M. (2008a), Fairness, Responsibility, and Welfare, Oxford University Press.

Fleurbaey, M. (2008b) Willingness-to-pay and the equivalence approach, Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, OPHI Working Paper No. 25.

Fleurbaey, M. (2009). Beyond GDP: The Quest for a Measure of Social Welfare. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(4), 1029–75.

Fleurbaey, M., & Gaulier, G. (2009). International Comparisons of Living Standards by Equivalent Incomes. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 111(3), 597–624.

Fleurbaey, M., & Maniquet, F. (2006). Fair Income Tax. Review of Economic Studies, 73(1), 55–83.

Fleurbaey, M., & Maniquet, F. (2011). A theory of fairness and social welfare. Cambridge University Press : Econometric Society Monographs.

Fleurbaey, M., & Trannoy, A. (2003). The Impossibility of a Paretian Egalitarian. Social Choice and Welfare, 21, 243–263.

Haan, P. (2006). Much ado about nothing: conditional logit vs. random coefficient models for estimating labour supply elasticities . Applied Economics Letters, 13, 251–256.

Haan, P. (2010). A Multi-State Model of State Dependence in Labor Supply, Labour Economics, 17, 323–335.

Haan, P., & Steiner, V. (2005). Distributional Effects of the German Tax Reform 2000—A behavioral microsimulation analysis, Schmollers Jahrbuch . Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 125, 39–49.

Hodler, R. (2009). Redistribution and Inequality in a Heterogeneous Society. Economica, 76(304), 704–718.

Jones, C. and Klenow P. (2010), Beyond GDP? Welfare across Countries and Time, NBER Working Paper No. 16352.

King, M. (1983). Welfare analysis of tax reforms using household data. Journal of Public Economics, 21, 183–214.

Lockwood, B. and Weinzierl, M., (2012), De Gustibus non est Taxandum: Theory and Evidence on Preference Heterogeneity and Redistribution, NBER Working Paper No. 17784.

Luttens, R., & Ooghe, E. (2007). Is it Fair to Make Work Pay? Economica, 74(296), 599–626.

Manski, C. (2012), Identification of Preferences and Evaluation of Income Tax Policy, NBER Working Paper No. 17755.

Pencavel, J. (1977). Constant-Utility Index Numbers of Real Wages. American Economic Review, 67(1), 91–100.

Preston, I., & Walker, I. (1999). Welfare Measurement in Labour Supply Models with Nonlinear Budget Constraints. Journal of Population Economics, 12, 343–361.

Schokkaert, E., & Van de gaer, D., Vandenbroucke, F. and Luttens, R. , (2004). Responsibility sensitive egalitarianism and optimal linear income taxation. Mathematical Social Sciences, 48(2), 151–182.

Schokkaert, E., Van Ootegem, L and Verhofstad, E. (2009), Measuring job quality and job satisfaction, FEB working paper 2009/620.

Steiner, V., Wrohlich, K., Haan, P., and Geyer J. (2008), Documentation of the Tax-Benefit Microsimulation Model STSM: Version 2008, Data Documentation 31, DIW Berlin.

Van Soest, A. (1995). Structural Models of Family Labor Supply: A Discrete Choice Approach. Journal of Human Resources, 30, 63–88.

Vermeulen, F. (2002). Collective household models: principles and main results. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16(4), 533–64.

Wagner, G., Frick, J., & Schupp, J. (2007). The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) - Scope, Evolution and Enhancements, Schmollers Jahrbuch. Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 127, 129–169.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to participants of the seminars “Basic Income Policies and Tax Reforms: Alternative Concepts and Evaluations” at the University of Turin, 19–20 November 2009, “Fairness, Equality of Opportunity and Public Economics” at CORE, Louvain-la-Neuve, 9–10 April 2010 and the EUROMOD workshop at ISER (University of Essex) 23–24 September 2010, for useful comments on the results presented in this paper. Peter Haan gratefully acknowledges financial support by the Thyssen Foundation in Project AZ.10.11.2.085. The usual disclaimer applies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Decoster, A.M.J., Haan, P. Empirical welfare analysis with preference heterogeneity. Int Tax Public Finance 22, 224–251 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9304-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-014-9304-5