Abstract

This paper examines endogenous timing in an international tax competition model. Unlike existing studies, governments are assumed to decide not only tax rates but also whether they are set early or late. The Nash equilibrium provides four conclusions for alternative double tax allowances. First, tax deductions cause simultaneous tax competition, whereas tax credits yield sequential tax competition. Second, any double taxation relief would generate capital trade. Third, a credit system could maximize one country’s economic welfare but would lower another country’s economic welfare more than a deduction regime. Fourth, a home country’s government would choose credit regimes under a maximax rule, but select deduction methods under minimax and maximin rules, while all double tax allowances are indifferent to a host country. The findings resolve the question raised by Bond and Samuelson (Economic Journal 99:1099–1111, 1989) of why governments choose tax credits when tax deductions are clearly better. Namely, this paper shows that one country is better off but another is worse off with credits rather than deductions. Accordingly, we cannot clearly specify whether governments choose credit systems or deduction regimes. The possible double tax allowances employed by the governments depend on their own decision criterion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Most countries use unlimited tax credits as the credit method. On the other hand, tax deductions are often prescribed by domestic tax law. Therefore, this paper focuses only on the two tax rules. However, we also have to note that some OECD countries employ an exemption system. In this case, no tax competition occurs because their governments renounce taxation on residents’ foreign investments. According to some national tax agencies, tax exemption seems to be employed from the viewpoint of its long-term advantages (to increase foreign retained earnings, for example). Therefore, tax exemptions should be investigated in a repeated game. We consider it as a special case of limited tax credits (see footnote 6).

Following Hamilton and Slutsky (1990), it is not restrictive if the governments are committed to move at the time they announce, because neither government reneges in any circumstance. If simultaneous play results from the announcement stage, then the governments have rejected being followers if they play early or being leaders if they play late. If simultaneous play is announced and one government delays until after the other has moved, then the outcome does not change. Similarly, if a sequential move outcome results from the announcement stage, either government could have achieved a simultaneous outcome but rejected it. Because a later mover observes the action of an earlier mover, the leader cannot switch its action without changing the follower’s choice.

Unlike Davies (2003), this model does not explicitly represent two-way capital flows. However, this does not mean that all capital mobility arises only because of the investment decisions of one country’s agents. Let us define capital flows as Z=X−X ∗, where X≥0 (X ∗≥0) denotes the level of foreign direct investment made by the home country’s capital owner (the foreign country’s capital owner) into the foreign country (the home country). Depending on the equilibrium capital flow and level of foreign direct investment, capital owners in either country or both countries have no income generated from investment abroad. Therefore either or both tax rules are irrelevant. In other words, the equilibrium capital flow, Z, depends on only the home country’s tax rule under Z>0 with X>X ∗=0, on only the foreign country’s tax rule under Z<0 with X ∗>X=0, or on neither under Z=0 with X=X ∗=0.

Strictly speaking, as in Hamada (1966), (1−t) can be considered as (1−β)/(1−α), where α∈[0,1) and β∈[0,1), respectively, denote the home country’s tax rate on the capital located within its territory and on the traded capital. Similarly, this model can consider (1−t ∗). If the foreign country’s government offers DED, Z<0 requires the condition

$$\bigl(1 - \alpha^{*}\bigr) \cdot F_{K}^{*}\bigl[ \bar{K}^{*}\bigr] < (1 - \beta^{*}) (1 - t) \cdot F_{K}[\bar{K}]\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad\bigl(1 - \alpha^{*} \bigr) < (1 - \beta^{*}) (1 - t) \cdot c, $$where α ∗∈[0,1) and β ∗∈[0,1), respectively, denote the foreign country’s tax rate on the capital located within its territory and on the traded capital. Because the condition is possible, Z<0 can occur in this model. A similar argument could apply for CRE as well.

It is not restrictive to focus only on the pure strategy. The Appendix extends the pure strategy to include the mixed strategy with respect to the timing of setting tax rates. However, the arguments find the same results as in the original game structure.

With the tax exemption, the home country’s tax rate is irrelevant because the equilibrium is Z>0. As a result, only the foreign country’s government could maximize its national income. In this case, the home country’s national income is Y CF , while the foreign country’s is \(Y_{\mathit{CF}}^{*}\).

References

Amir, R. (1995). Endogenous timing in two-player games: a counterexample. Games and Economic Behavior, 9, 234–237.

Amir, R., & Stepanova, A. (2006). Second-mover advantage and price leadership in Bertrand duopoly. Games and Economic Behavior, 55, 1–20.

Becker, J. (2009). Taxation of foreign profits with heterogeneous multinational firms. CESIFO working paper No. 2899.

Bond, E. W., & Samuelson, L. (1989). Strategic behaviour and the rules for international taxation of capital. Economic Journal, 99, 1099–1111.

Davies, R. B. (2003). The OECD model tax treaty: tax competition and two-way capital flows. International Economic Review, 44, 725–753.

Feldstein, M., & Hartman, D. (1979). The optimal taxation of foreign source investment income. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 93, 613–629.

Gibbons, R. (1992). Game theory for applied economists. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hamada, K. (1966). Strategic aspects of taxation on foreign investment income. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80, 361–375.

Hamilton, J. H., & Slutsky, S. M. (1990). Endogenous timing in duopoly games: Stackelberg or Cournot equilibria. Games and Economic Behavior, 2, 29–46.

Harsanyi, J. C., & Selten, R. (1988). A general theory of equilibrium selection in games. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Janeba, E. (1995). Corporate income tax competition, double taxation treaties, and foreign direct investment. Journal of Public Economics, 56, 311–325.

Kempf, H., & Rota-Graziosi, G. (2010). Endogenizing leadership in tax competition. Journal of Public Economics, 94, 768–776.

Musgrave, P. B. (1969). United States taxation of foreign investment income: issues and arguments. Cambridge: Law School of Harvard University.

Oakland, W. H., & Xu, Y. (1996). Double taxation and tax deduction: a comparison. International Tax and Public Finance, 3, 45–56.

Ruffin, R. J. (1984). International factor movements. In R. W. Jones & P. Kenen (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (Vol. 1, pp. 237–288). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Saloner, G. (1987). Cournot duopoly with two production periods. Journal of Economic Theory, 42, 183–187.

Tewari, D. D., & Singh, K. (2003). Principles of microeconomics. New Delhi: New Age International.

Wildasin, D. E. (1991). Some rudimentary “duopolity” theory. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 21, 393–421.

Wilson, J. D. (1986). A theory of interregional tax competition. Journal of Urban Economics, 19, 296–315.

Wilson, J. D. (1999). Theories of tax competition. National Tax Journal, 52, 269–304.

Zodrow, G. R., & Mieszkowski, P. (1986). Pigou, Tiebout, property taxation, and the underprovision of local public goods. Journal of Urban Economics, 19, 356–370.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

This appendix extends the pure strategy to include the mixed strategy with respect to the timing of setting tax rates. The analytical method follows Gibbons (1992). Suppose that the home country’s government believes that the foreign country’s government will play first with probability f∈[0,1] and second with probability (1−f). That is, the home country’s government believes that the foreign country’s government will play the mixed strategy {f,1−f}. Let {h,1−h} denote the mixed strategy in which the home country’s government chooses first with probability h∈[0,1]. For each value of f between zero and one, we now compute the value of h, denoted \(\hat{h}(f)\), such that {h,1−h} is the best response for the home country’s government to {f,1−f} by the foreign country’s government.

We will begin with the analysis of DED. The home government’s expected payoff from playing {h,1−h} when the foreign country’s government play {f,1−f} is

where both (Y DH −Y DS ) and (Y DS −Y DF ) are positive from Lemma 3. Accordingly, (16) is increasing in h, because f is between zero and one. This result means that the home government’s best response is h=1 (i.e., first) for any value of f between zero and one. An analogous discussion would indicate that the foreign government’s best response is f=1 (i.e., first) for any value of h between zero and one. Consequently, only DED would cause an equilibrium (i.e., h=1 and f=1). That is, both governments select first in the equilibrium under DED.

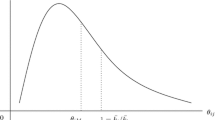

Next, let us examine the case of CRE. The result is summarized in Fig. 3. The home government’s expected payoff from playing {h,1−h} when the foreign country’s government is playing {f,1−f} is

where both (Y CH −Y CS ) and (Y CF −Y CS ) are positive from Lemma 4. Letting ϕ ∗ denote (Y CH −Y CS )/{(Y CH −Y CS )+(Y CF −Y CS )}, (17) is increasing in h as f<ϕ ∗, and is independent of h as f=ϕ ∗, as well as decreasing in h as f>ϕ ∗. Accordingly, the home government’s best response is h=1 (i.e., first) if f<ϕ ∗ and h=0 (i.e., second) if f>ϕ ∗, as indicated by the two horizontal segments of \(\hat{h}(f)\), or AD and BE in Fig. 3.

On the other hand, the home government’s expected payoff (17) is independent of h when f=ϕ ∗. In this case, the home country’s government is indifferent among all the mixed strategies {h,1−h}. That is, when f=ϕ ∗ the mixed strategies {h,1−h} are a best response to {f,1−f} for any value of h between zero and one. Thus, \(\hat{h}(\phi^{*})\) is the entire interval [0,1], as indicated by the vertical segment of \(\hat{h}(f)\), or DE in Fig. 3. Similar reasoning can derive the value of f, denoted \(\hat{f}(h)\), such that {f,1−f} is a best response for the foreign country’s government to {h,1−h} by the home country’s government. This result is illustrated as the kinked segments AFCGB in Fig. 3.

When the tax rule is CRE, therefore, the equilibria can occur at three intersections of \(\hat{h}(f)\) and \(\hat{f}(h)\) in Fig. 3. The first equilibrium (i.e., h=1 and f=0) corresponds to point A, and the second equilibrium (i.e., h=0 and f=1) coincides with point B. In the two equilibria, one country’s government chooses first, and another country’s government selects second. Moreover, the third equilibrium (h=ϕ and f=ϕ ∗) occurs at point C. It means that the home country’s government chooses first with probability ϕ where ϕ denotes \((Y_{\mathit{CF}}^{*} - Y_{\mathit{CS}}^{*})/\{(Y_{\mathit{CF}}^{*} - Y_{\mathit{CS}}^{*})+ (Y_{\mathit{CH}}^{*} - Y_{\mathit{CS}}^{*})\}\). Meanwhile, the foreign country’s government selects first with probability ϕ ∗.

According to Lemma 4, the home and the foreign payoffs are, respectively, Y CH and \(Y_{\mathit{CH}}^{*}\) in the first equilibrium (i.e., h=1 and f=0) and Y CF and \(Y_{\mathit{CF}}^{*}\) in the second equilibrium (i.e., h=0 and f=1). In these cases, one country’s government could maximize its national income, while the other one could avoid the greatest damage. When we compare the two equilibria, hence, we cannot say that one dominates the other. In the third equilibrium (i.e., h=ϕ and f=ϕ ∗), both governments would gain the expected payoffs where the weights are the probabilities (ϕ,ϕ ∗). Because the expected payoffs of the home and foreign countries include, respectively, Y CS and \(Y_{\mathit{CS}}^{*}\), i.e., the lowest level of their own national incomes, the third equilibrium cannot allow both countries to be better off than the other. Even if we consider the risk-dominance criteria as defined by Harsanyi and Selten (1988), it is ambiguous whether the third equilibrium is dominant and plausible. Therefore, it is impossible to select a convincing equilibrium under CRE.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ida, T. International tax competition with endogenous sequencing. Int Tax Public Finance 21, 228–247 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9264-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9264-6

Keywords

- International tax competition

- Endogenous timing

- Double tax allowance

- First/second-mover advantage

- Strategic substitutes/complements

- Decision rules