Abstract

The Business Correspondent (BC) model is an IT-enabled business process outsourcing initiative to provide financial services to the unbanked. It is a complex banking system involving multiple actors, system elements and settings, intended to address financial exclusion. Given the BC-Model’s potentially significant role in economic sustainability, it is important to evaluate its success. Efforts to measure the success of the BC-Model have been limited to date; this paper therefore presents a conceptual framework of BC-Model-Success consisting of six dimensions- economic, strategic, technological, customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and social, resulting from a three-phase study design. The relevance of the framework was empirically validated across four implementations of the BC-Model. The resulting framework provides strong theoretical foundations for understanding what BC model success is, for assisting practitioners with evaluating the success of the BC-Model and with identifying possible improvements, and for facilitating future research on the BC-Model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) is increasingly prevalent, enabling organizations to outsource non-core activities, thereby achieving cost reduction and increased focus on higher value-adding and strategically important core activities (Gewald & Dibbern, 2009). BPO entails the delegation of one or more business processes to an external service provider who owns, administers, and manages the processes, based on a defined and measurable set of performance metrics (Gartner, 2022). While there are many documented advantages of BPO, its usage for sustainable social development remains an area lacking research. Scholars have called for action, explaining that one of the promising areas of future research is to investigate how BPO can serve as a means to alleviate poverty or uplift marginalized sections of society (Khan et al., 2018; Lacity et al., 2016; Sandeep & Ravishankar, 2015).

Financial exclusion, where people lack ready access to a country’s formal financial system (Sarma & Pais, 2011) is a contributor to social exclusion and poverty. Approximately, 1.7 billion adults, close to one third of the world’s adult population, do not have ready access to financial services (The World Bank, 2018). The goal of financial inclusion is to provide financial services to these unbanked people. Financial inclusion has been identified as an enabler for 7 of the 17 global sustainable development goals (The World Bank, 2018). Since 2010, 55 countries have made commitments toward financial inclusion (The World Bank, 2018). The Business Correspondent (BC) model is a business process outsourcing initiative designed to address the goal of financial inclusion (Kolloju, 2014). It is a technology supported agent-based service delivery model in which individual Business Correspondents (BCs) facilitate transactions. This structure, an alternative to the traditional branch-based structure, enables public sector banks to use the services of non-governmental organizations or self-help groups, Micro Finance institutions, and other Civil Society organizations as intermediaries in providing financial and banking services (Bhaskar, 2006). The model primarily aims to reach geographically diverse populations, particularly in rural areas, where people do not have access to mainstream banking institutions using mobile baking technology.

The BC-Model, yet in its genesis, will benefit from careful research into its success. Little formal research has been reported, and various consultancies (GrameenFoundation, 2013; College of Agricultural Banking et al., n.d.; Sa-Dhan, 2012) have reported that the area has much potential, but is understudied. To rigorously evaluate the impact of such an initiative and guide its improvement, strong and valid measures of its level of success are required. Success is an elusive concept, often ill-defined, and with no standard measures that can be used as-is (Larsen & Myers, 1997); this is the case for the BC-Model as well. Current efforts to measure BC-Model-Success have been ad-hoc and descriptive.

Researchers invent constructs to designate conceptual abstractions of a phenomenon. Good research depends on a clear understanding of constructs (Zhang et al., 2016b) as ambiguous constructs will jeopardize construct validity (Schwab, 1980). The importance of conceptualization has been well argued (MacKenzie et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016a). There are varied understandings of conceptualization (Zhang et al., 2016a). To many researchers, conceptualization entails providing a definition of the construct that captures its main dimensions (MacKenzie et al., 2011), which can then be used to understand measures and operationalise the construct.

For the BC-Model to progress as a technology-enabled financial inclusion initiative, its success needs to be evaluated rigorously, which in turn will contribute to more systematic and integrative inquiries into this emerging phenomenon. This study aims to address this gap, focusing on the Indian implementation of the BC-Model introduced in 2006 (RBI, 2010), and adopting the overarching research question: How can BC-Model-Success be conceptualized? To address this overarching question, the study aims to address two investigative questions (following Emory & Cooper, 1991): (i) What dimensionsFootnote 1 characterize the success of the BC-Model? and (ii) What are the measuresFootnote 2 that anchor these dimensions? The aim of this work is to qualitatively derive a conceptual framework that can be adapted to different implementations of the BC-Model to evaluate the success of the model. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to devise a conceptual framework for BC-Model-Success.

Development of the conceptual framework in this study addresses research and advancement at the interface of IS/IT in academia and industry. The conceptual framework gives both researchers and practitioners a running-start with evaluation of the Business Correspondent Model and with evaluating similar or analogous BPO initiatives. Such evaluation potential will encourage pragmatic solutions to implementation problems associated with technology enabled BPO initiatives. The conceptual framework can be used to define the dimensions and measures of success systematically, thereby informing BC-Model operations-related decisions. For researchers, the study offers a partially validated analytic theory and model of BC-Model-Success, the BC-Model being an instance of an IS/IT system and a promising solution to the global problem of sustainable financial inclusion.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of concepts related to this study. Section 3 presents the methodology employed in this study. Section 4 illustrates the findings, which include literature-based findings (Sect. 4.1 and 4.2), and case study findings (Sect. 4.3), including the revised conceptual model (Sect. 4.3.6). Section 5 concludes the paper with an overview of contributions, limitations, and future work.

2 Related Work and Background

This section presents an overview of concepts that led to the genesis of the Business Correspondent Model as well as an introduction to the model itself. Thereafter, the theoretical underpinnings pertaining to the proposed work, is briefly introduced.

2.1 Financial, Digital and Social Inclusion

Financial inclusion ensures that individuals, especially poor people, have access to basic financial services in a formal financial system (Allen et al., 2016; Ozili, 2021). The benefits of financial inclusion have received much attention from academics and practitioners. First, financial inclusion is considered as a major strategy to achieve United Nation’s sustainable development goals (Demirgüç-Kunt & Singer, 2017), second, it helps to improve the level of social inclusion in societies (Ozili, 2020), third, financial inclusion helps to reduce poverty to a minimum level (Neaime & Gaysset, 2018), and finally, financial inclusion entails other socio-economic benefits (Nandru & Rentala, 2019; Zauro et al., 2020). Financial inclusion enables access to financial services, which is considered an essential public good, enabling society to enjoy the benefits of a modern market economy (Joia & dos Santos, 2019). These factors have motivated several countries to continue to commit significant resources to increasing the level of financial inclusion (Ozili, 2021).

Financial inclusion is related to digital and social inclusion. Digital inclusion can be defined as the capability of individuals to get equitable access to and use of information and communication technology for participation in society (Helsper, 2008). Digital inclusion aims at enabling people to use information and technology for participation in social and economic life, including banking services (Antoninis, 2018; Goel et al., 2021). Digital inclusion is of critical importance for countries because of adoption of new technologies and digital transformation by governments, businesses, and societies around the world, which requires people to be equipped with digital knowledge and skills (Goel et al., 2021). In recent years, technological innovations have allowed access to more efficient digital financial services (Lyons et al., 2020). Financial inclusion promotes people to use digital services for banking purposes, thereby contributing to digital inclusion. Digital inclusion strategies can also foster financial inclusion, as people who are confident in using digital services are more likely to use digital financial services. Additionally, digital inclusion has also been cited significant in reducing the difference between the richest and poorest societies (Joia & dos Santos, 2019). Social inclusion can be defined as “the extent that individuals…are able to fully participate in society and control their own destinies” (Warschauer, 2004). Social inclusion aims at ensuring all members of society have equal access to same opportunities (Martin & Cobigo, 2011). Financial inclusion improves access to finance for members of the society through financial innovations contributing to improved livelihood, reduction of poverty, and social inclusion (Ozili, 2020). Social inclusion also assists in financial inclusion by laying out policies that promote access to financial services by the poor and low-income individuals and is not influenced by social discrimination (Ozili, 2020). Furthermore, digital inclusion also promotes social inclusion as digital technologies are vehicles to promote participation in society (Andrade & Doolin, 2016).

The discussion conveys that financial inclusion, social inclusion, and digital inclusion are concepts related to one another and of priority for nations around the world as they help in socio-economic development of the country (Allen et al., 2016). Several initiatives are being taken by governments around the world to accomplish these objectives (Ozili, 2020). The Business Correspondent Model is one such initiative.

2.2 Introducing the Business Correspondence Model

The Business Correspondent (BC-Model) is a financial inclusion initiative introduced in 2006 by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to provide rural people with accessible financial services (RBI, 2010). The initiative is also expected to contribute to social inclusion by improving the livelihood of people and digital inclusion by encouraging people to use digital technology for financial services. India is an under-banked country (Bihari, 2011); the country’s banking system does not work well for poor and hard-to-serve populations. One of the primary reasons for this is that India remains a cash-based economy, and bricks and mortar branches make cash-based transactions expensive. Opening a bank account to save small amounts of money is not perceived to be of much value to low-income households. The inflexibility of the banks regarding documentation, as well as the limited literacy of the poor and hard-to-serve population, further hinders branch-based banking. The costs banks incur in handling transactions is passed on to these people with low income, which is difficult for them to absorb. Additionally, transacting with branches of the banks requires a visit, which reduces the customer’s work hours and their daily wage (Sakariya, 2013). Inability to access financial services and disparity in financial needs leaves poor households languishing. Such financial exclusion entails opportunity costs for the poor, which is why there is a need for such households to have access to a suite of appropriate products and services (RBI, 2016). Accelerating advancements with technology are creating opportunities to connect poor households with financial facilities. A revolutionary IT-enabled approach for delivery of financial services to the unprivileged is the BC-Model.

The BC-Model was initiated to address the scarcity of manpower required to reach large numbers of people via the branch-based banking system. The BC-Model aims to reach geographically diverse populations, particularly in rural areas, where people do not have access to mainstream banking institutions. The model involved multiple actors: the bank, the Business Correspondent (BC) Agency, the Business Correspondent (BC), and the customer. Under the governance of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), non-bank agents called Business Correspondents are permitted to carry out financial transactions on behalf of the bank; this is also referred to as ‘branchless banking’ (Kolloju, 2014). With the BC-Model, in areas that are inaccessible to banks, entities such as grocery stores, petrol stations, and other companies with retail networks, can be authorized to perform financial operations on behalf of the bank. These entities are operated by BCs and work under the guidance and administration of an intermediary organization, known as the BC agency. The agency hires and pays commission to the BCs for the transactions they undertake and also addresses their training needs. BCs are typically grassroots entrepreneurs who serve as contractual representatives of the sponsor bank and are authorized to conduct operations on behalf of the bank. Every BC works for a bank and is under the surveillance of a BC agency. The banks are hence at the apex and recruit the BC agency to conduct financial services on behalf of the bank. The customers use the financial services provided by the model.

There are several policies which regulate the BC-Model. The Reserve Bank of India specifies that the BCs can offer only four products: (i) savings account with overdraft facility, (ii) remittance facility, (iii) savings products, and (iv) entrepreneurial credit products such as Kisan Credit Card (KCC) or General-Purpose Credit Card (GCC). This is also a limitation for users as not all services are offered at this stage. Each BC agency’s policies impose restrictions on the way a BC functions (Kolloju, 2014). Not all financial services may be provided. For instance, currently the BCs cannot provide loans in India. The model is further restricted by the bank’s policy in terms of the amount of cash the BCs can handle. In terms of income, the bank earns through the value of transactions, the BC agency earns through the bank, and the BCs earn commission from the bank as agreed in their contract (Jain, 2015). The salary of a BC is comprised of a base salary and the commission. The objective of the bank, the BC agency, as well as the BC is to have increased transactions as that would result in their profits as well as serve the purpose of the model.

The BC-Model is a combination of an IT system and supporting ICT infrastructure, multiple actors, and policies enabling non-banking institutions to provide banking services to customers. Technology plays a central role in the BC-Model. The BC agencies need a robust technology platform that can support a large volume of transactions in a fast and secure manner, which are facilitated by many BCs. Likewise, the bank’s technology platform must be able to interface with the BC agencies’ platforms, which may be of varying complexity and capability. The technology solutions should be integrated into the workflow of both the banks and the intermediaries. Furthermore, the technology needs to be embedded with features that makes financial transactions and banking services understandable by users with varying degrees of literacy. For example, voice enabled technology is required so that customers who are not able to read can listen to the transactions that are happening. Micro ATMs, as well as mobile ATMs, play a significant role in this model as they help to connect the BC’s transactions with the banking system. These devices need to be able to process several transactions remotely for effective use. Mobile banking technology also plays an important role in the BC-Model. The BC agency, BCs, and customers receive notifications related to operations on their mobile. The technology used in the model can be in-house or provided by a technology vendor. In either case, with evolution in technology and needs of customers, the technology requires frequent updates. The customers use their AadhaarFootnote 3 number (their unique identification number) as well as their fingerprints to connect with the core banking system and conduct transactions (Kapoor & Shivshankar, 2012). Aadhar enabled Payment Systems (AePS) needs to be used by the banks, agencies, and BCs. These aspects make the BC-Model a complex and unique systems-enabled banking system. From the preceding, it can be seen that the BC-Model functions as a business process outsourcing model, where certain financial services are conducted by the BCs on behalf of the bank and the BC administration is outsourced to the BC agency.

While the BC-Model has been implemented in India for more than a decade and progress has been considerable, it is still far below expectations (Qazi, 2019). According to the Findex report (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2017) 80% of Indians have a bank account. However, 48% of these bank accounts have seen no transactions since being opened. Furthermore, additional studies indicate that the BC-Model is not performing in an optimal manner (Mehrotra et al., 2018; Uzma & Pratihari, 2019). There is a growing need to understand the facets contributing to the success of the BC-Model (Uzma & Pratihari, 2019).

This raises concerns and requiring further investigation to understand what comprises BC-Model-success. There have to date been limited attempts to measure the success of the BC-Model. To the best of our knowledge, there is no empirical work that presents a conceptual framework which can be used to evaluate the success of the BC-Model. While some consultancy reports discuss the success of the BC-Model (GrameenFoundation, 2013; Sa-Dhan, 2012), the only measure they use is ‘profitability’. And though prior research reinforces the requirement that the model be profitable for banks in order to ensure sustainable operations (GrameenFoundation, 2013; Uzma & Pratihari, 2019), given the broader goals of the BC-Model (i.e., primarily devised to achieve the goal of financial inclusion), a solely profit-oriented view is blinkered. Success is a multi-dimensional concept, where different dimensions may mean different things to different stakeholders at different times and for different projects (Gable et al., 2008; Shenhar et al., 2001; Wach et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2013). Prior work conveys limited conceptual understanding of what is BC-Model-success. There is hence a need to understand the dimensions that characterize the success of the BC-model and the measures which anchor these dimensions, along with an understanding of what these different dimensions mean to stakeholders involved in the BC-Model. Such understanding will inform more useful evaluation of the BC-Model in-situ. This study aims to address this gap by deriving a conceptual framework for holistic understanding and evaluation of BC-Model-success.

2.3 Theoretical Underpinnings

This study aimed to develop a conceptual framework, to better understand ‘what-is’ BC-Model-Success. Confused and ambiguous conceptual definitions engender misunderstanding and inconsistent measures of a concept (Wacker, 2004). Inability to appropriability define a construct may result in invalid conclusions about relationships with other constructs due to deficient indicators (MacKenzie et al., 2011). Therefore, following Burton-Jones and Straub (2006), we first identified the structure, i.e., definition of BC-Model-Success, followed by items to operationalize BC-Model-Success. We adapted several theoretical underpinnings to guide this conceptualization effort. Furthermore, prior developments from proxy domains (in this case BPO) were sought and adapted as the theories that underpinned the conceptual development of the BC success model. These are briefly introduced here and referred to in detail in upcoming sections.

We followed Zmud and Boynton (1991), who state that “one should never develop an instrument from scratch when a well-developed, or fairly well-developed instrument that fits the level of analysis and level of detail required by a particular research model already exists”. Our review of BC-Model literature revealed a dearth of prior research that focussed on conceptualising or understanding what entails BC-Model-Success. We hence looked at proxy domain, Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) literature, to identify ‘well-developed’ BPO success instruments that could be adapted for this work. The Grover et al. (1996) and Lee and Kim (1999)’s frameworks were selected as proxy frameworks to start our conceptualization efforts. How they were identified and adapted was part of the overall methodology deployed and is explained in detail in Sect. 4.1.

Grover et al. (1996) aimed to identify determinants of BPO success for various Information Systems functions. They present an instrument with three dimensions of BPO success (namely ‘economic’, ‘strategic’ and ‘technological’) and nine measures. Lee and Kim (1999) aimed to build on prior work and added a new perspective to BPO success, ‘user satisfaction’. They used Grover et al (1996)’s instrument and added new measures related to user satisfaction to it. They present 4 dimensions and 15 measures for BPO success. Both these instruments are widely cited, used, and adapted in BPO literature, which is why they were considered well-developed and suitable to use and adapt for this study.

3 Research Methodology

Three phases were undertaken in order to derive a conceptual framework for BC-Model-Success. Each of these phases are discussed next.

In the first phase (Phase 1), we searched to see if a “well-developed, or fairly well-developed instrument that fits the level of analysis and level of detail required” (following Zmud and Boynton (1991), p. 154) existed that could be used to evaluate BC-Model-Success. A systematicFootnote 4 literature review was conducted. We started with the keywords “Business Correspondent Model” AND “Success” as well as “BC Model” AND “Success”. The preliminary search revealed a dearth of relevant literature. While papers did mention the BC-Model, they did not evaluate its success. Given the BC-Model is a business process outsourcing (BPO) initiative, we next reviewed the BPO literature for broader definitions and measures of BPO success. The search string (“Business Process Outsourcing success” OR “BPO success”) anywhere in the text, was used to identify papers that had operationalized BPO success. Since this string did not provide many relevant results, we expanded our study to see if BPO benefits or outcomes were measured in other forms (as has been done in other success measurement literature such as Bharadwaj & Saxena, 2009; Gewald & Dibbern, 2009)). The databases searched were the main IS and Management databases; ABI inform, EBSCOHost, JSTOR, ProQuest and Science Direct. Only peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings (in English) were searched. The search yielded 45 articles. These articles were reviewed to retrieve BPO success definitions, the key dimensions of BPO success, and associated measures.

In the second phase (Phase 2), BPO success definitions and measures were adapted for the context of the BC-Model. From the BC-Model literature (specifically in the Indian context) we identified characteristics unique to the BC-Model and assessed completeness of the adapted measures. The BC-Model literature, in particular consultancy reports, enabled the researchers to obtain a broader contextual overview of the BC-Model, such as understanding outcomes the model aims to achieve and issues impeding success of the BC-Model. At the end of Phase 2 we had our literature-driven BC-Model-Success conceptual framework.

In the third phase (Phase 3), we used multiple case studies to assess applicability, for content validity, and to re-specify (as necessary) our a-priori framework in the BC-Model context. Case study is a method that “examines a phenomenon in its natural settings, employing multiple methods of data collection to gather information from one or few entities” (Benbasat et al., 1987). Case study research is a scientific way to research an area that is emerging where there is little research to date (Lee, 1989); “Case research is particularly appropriate for certain types of problems: those in which research and theory are in their early formative stages” (Benbasat et al., 1987). Thus, the case study method is well suited to this study, as BC-Model-Success is not well-researched and warrants study in its natural context. Prior work has advocated the use of case studies, in particular positivist case study (as per Sarker et al. (2018)), in IS research to test theories (Dubé & Paré, 2003; Paré, 2001; Shanks, 2002), which in this case is our a-prior BC-Model-Success conceptual framework. With our case studies, we placed specific emphasis on the content validity of the forming conceptual framework and its elements. While content validity may be associated as a quantitative approach, in IS research, qualitative approaches such as case studies are commonly used for testing new conceptualizations (Tojib & Sugianto, 2006), which is how the cases were used in this paper. We also conducted pattern matching for validation of the content (i.e., dimensions and measures of the BC-Model-Success framework) across multiple case studies.

At the end of Phase 3, we derived a conceptual framework for BC-Model-Success, which had dimensions and measures unique to the context of the BC-Model.

4 Findings

Here we present the outcome of the three phases employed in this study.

4.1 Phase 1: Literature Based Extraction of Content: Definition(s) and Measures of BPO Success

The primary aim of this phase was to benefit as far as possible from prior good work or researchers and build upon it. Given the paucity of literature specifically on BC-Model-Success, we looked at proxy literature on ‘BPO success’ to understand how it has been defined by researchers and how measures of BPO success were derived (if at all). In our review we found that most of the articles that mentioned ‘BPO success’ did not measure BPO success, but rather explored its antecedents. Subsequently, only empirical papers that clearly measured BPO success were included, which resulted in a sample of 7 relevant papers out of 45 first distilled. Table 1 provides an overview of these 7 papers. Column 1 lists the definition of BPO success as used by the author(s) and column 2 lists the dimensions or measures used to operationalize BPO success, along with the type of study (qualitative/ quantitative). The bold and italicized words in the second column are the items used by the authors to measure BPO success.

While the above papers operationalized BPO success (in different contexts), two general outsourcing papers were found to be widely cited across the BPO success literature (all 7 of the BPO articles in Table 1 cited either one or both the articles). In fact, the measures used by the above-mentioned papers were adapted from those two papers.

The first article was by Grover et al. (1996), which states that the success of outsourcing can be assessed in terms of attainment of its benefits, categorized as ‘economic’, ‘strategic’ and ‘technological’. To measure overall outsourcing success, they used another variable, ‘satisfaction’ which according to them, is considered the best surrogate to capture “affective and cognitive components of humans” (Grover et al., 1996, p. 98). They devised nine measures to assess the degree to which service users were satisfied with respect to the four categories. The four categories (and nine measures) they used to encompass the domain of outsourcing success are detailed following.

Economic Category

Economic benefits “refer to the ability of a firm to utilize expertise and economies of scale in human and technological resources of a service provider and to manage cost structures through unambiguous contractual arrangements” (Grover et al., 1996, p. 93). The measures used were: ‘we have enhanced economies of scale in human resources’, ‘we have enhanced economies of scale in technological resources’ and ‘we have increased control of IS expenses’.

Strategic Category

According to Grover et al., (1996, p. 93) strategic benefits “refer to the ability of a firm to focus on its core business, outsource routine IT activities so that it can focus on strategic uses of IT, and enhance IT competence and expertise through contractual arrangements with an outsourcer”. Based on this definition, the measures used were: ‘we have been able to refocus on core business’, ‘we have enhanced our IT competence’ and ‘we have increased access to skilled personnel’.

Technological Category

Technological benefits “refer to the ability of a firm to gain access to leading edge IT and avoid the risk of technological obsolescence that results from dynamic change of IT” (Grover et al., 1996, p. 93). Measures used were: ‘we have reduced risk of technological obsolescence’ and we have increased ‘access to key IT’.

Satisfaction Category

Success of outsourcing is defined as “satisfaction with the benefits from outsourcing gained by an organization as a result of deploying an outsourcing strategy” (Grover et al., 1996, p. 95). The measure used here was ‘we are satisfied with overall benefits from outsourcing’.

Subsequent to Grover et al. (1996), Lee and Kim (1999) defined outsourcing success as the ‘level of fitness’ between customer requirements and outsourcing outcomes. They measured outsourcing success from both a business and a user perspective. For the business perspective, they used the Grover et al. (1996) dimensions (economic, strategic, technological, and satisfaction) and measures. For the user perspective, they proposed new measures to assess satisfaction, defining it as “the degree of quality of offered services by the services provider” (Lee & Kim, 1999). They assessed satisfaction using the measures: reliability of information, relevancy of information, accuracy of information, currency of information, completeness of information, and timeliness of information.

An analysis of these two highly cited papers resulted in four categories of BPO success: (i) economic (all measures from Grover et al. (1996)), (ii) strategic (all measures from Grover et al. (1996)), (iii) technological (all measures from Grover et al. (1996)), and (iv) satisfaction (one measure from Grover et al. (1996) and six from Lee and Kim (1999)). To confirm that we accounted for all relevant measures that evaluate BPO success, we mapped the success measures identified in the BPO Success literature (see Appendix A) to the combination of categories from Grover et al. (1996) and Lee and Kim (1999). Henceforth, we refer to the four categories as the four ‘dimensions’ of BPO success, as we believe they collectively form BPO success. We first populated the table in Appendix A with all the measures derived from the two highly-cited papers (that is Grover et al., 1996 and Lee & Kim, 1999). We then mapped the measures (or adapted versions) used by other authors against these original measures to reveal any new measures (‘Other row’) that other papers operationalizing BPO success may have introduced.

Overall, all the measures found in the other papers mapped onto the four dimensions, instantiating all dimensions proposed by Grover et al., (1996) and Lee and Kim (1999).

In summary, in relation to the four dimensions of BPO success, three strategic measures, three economic measures and two technological measures (as suggested by Grover et al. (1996)) as well as seven measures for satisfaction (one from Grover et al. (1996) and six from Lee and Kim (1999)) were selected to be adapted to the BC-Model context. Furthermore, the papers highlighted that the economic, strategic, and technological dimensions are used to assess BPO success from a business perspective, whereas satisfaction is assessed from user’s perspective. How these were adapted is discussed in the next section.

4.2 Phase 2: Adapting BPO Definitions and Measures to Fit the Context of the BC-Model

Confused and ambiguous conceptual definitions engender inconsistent understanding and conflicting metrics for the same concept (Wacker, 2004). Many researchers assume they have a clear appreciation of the concept(s) they are researching and measuring, but later realize their concepts are vague, often after considerable effort has been invested in collecting data, recovery from which can be costly (DeVellis, 2012). Hence, it was essential to first define BC-Model-Success prior to arriving at measures to operationalize BC-Model-Success (MacKenzie et al., 2011). An understanding of the BPO success definitions as well as the dimensions from Grover et al. (1996) and Lee and Kim (1999), revealed four dimensions of BPO success: economic, strategic, technological, and satisfaction. Based on this comprehension, we define BC-Model-Success as “the ability of the model to achieve its intended strategic, economic, and technological benefits as well as satisfy its stakeholders”.

Next, to adapt the BPO success measures to the BC-Model, we used BC-Model literature to contextualize and understand the characteristics unique to the BC-Model. All the measures were found useful and important for the context of the BC-Model and hence all were adapted, as presented in the second column of Table 2. Further, three new measures were added based on insights obtained from the BC-Model literatureFootnote 5: sustainability, transparency of information, and co-operation and coordination. A number of practice-based working groups had been formed (GrameenFoundation, 2013; Sa-Dhan, 2012), seeking to understand the factors hindering success of the BC-Model. They published reports on the performance of the BC-Model conveying lack of transparency of information and coordination among BC agency and BCs as impediments to the success of the BC-Model. Considering one of the strategic goals of the model is to be sustainable (Uzma & Pratihari, 2019), this was added as a measure under the strategic dimension. Review of consultancy reports (IFMR, 2013; Kumari et al., 2014; MicroSave, 2014) indicated issues regarding transparency of information among the stakeholders as well as lack of cooperation and co-ordination hampering satisfaction of stakeholders thereby impeding progress of the model. These factors were therefore added as success measures under the satisfaction dimension.

Table 2 presents the outcomes of this phase, depicting the items adapted to measure the success of the BC-Model. We also evaluate the importance of each dimension for different stakeholders involved in the BC-Model and hence identify potential respondents for each measure within different dimensions. This is present in column 3 of Table 2.

4.3 Phase 3: In-depth Case Studies

This section provides details regarding the case studies that were conducted for content validity of the measures of the BC-Model-Success.

4.3.1 Overall Case Study Design

Multiple positive case studies were conducted to validate the content of the a-priori BC-Model-Success conceptual framework. The unit of analysis for this study was the ‘implemented BC-Model’ in a bank, similar to Yin’s (2009) ‘program’ type of unit of analysis. Tellis (1997), suggests careful consideration of cases available for study to maximize what can be learned over a period of time. A wide range of factors were considered when selecting the case types: type of bank, population being served, implementation of BC-Model and the number of branches of the bank across India (as an indicator of size). The goal was to capture a broad range of contextual issues in the sample (see Table 3). For deciding the number of case studies, researchers should consider resource constraints, opportunities and feasibility issues (Tellis, 1997). Eisenhardt (1989) suggests that “while there is no ideal number of cases, a number between 4 and 10 cases usually works well”. In this study, considering the extensive nature of each case study, the researcher conducted four case studies (referred to as; ‘Bank A’, ‘Bank B’, ‘Bank C’ and ‘Bank D’ to maintain anonymity in accordance with the research ethics agreements). Further, on analysis of cross-case results (see Sect. 5), which included pattern-matching (Yin, 2010), it was found that the results were similar across the four case studies; suggesting that the number of cases supported data and analytical saturation (Miles et al., 2014).

Reliability was enhanced by the detailed case study protocol and the structured case database (maintained using the NVivo tool), which provided the chain of evidence to effectively compare and synthesize the results. Predictive validity was increased by the application of prior-established data analysis techniques such as pattern matching (Yin, 2009). External validity was established (to a certain degree) by using multiple case studies and multiple stakeholders.

4.3.2 Introducing the Case Studies

The four case studies are introduced briefly here. Further details of each Bank’s background is presented in Appendix B.

Bank A is a private sector bank and has approximately 4000 branches throughout India, serving both rural and urban populations. It has been involved in BC-Model operations for the past 7 years and is actively involved in enabling the Indian government to achieve the goal of financial inclusion. It has launched two internal bank initiatives: The rural initiative group is primarily involved with the BC-Model, which is the focus of this study. Under the second scheme, the sustainable livelihood initiative, the bank provides finance to the underprivileged to start small businesses without any collateral (or security). The bank hence has already made a strong contribution to the goal of financial inclusion.

Bank B is a public sector bank with 7000 branches across India serving both rural and urban populations. The BC-Model was implemented in 2006. Bank B is a well-known public sector bank and is easily accessible given its large number of branches across India. The bank’s active involvement in the goal of financial inclusion was reinforced by the manager’s participation in various government campaigns related to rural uplifting.

Bank C is a regional rural bank, with 400 branches in India. Being a regional rural bank, it serves rural and semi-urban populations and hence is committed to the upliftment of rural areas. The BC-Model was implemented in 2011. The bank is committed to the goal of digital India, of which the banking sector forms an important component. Digital India aims at digital empowerment, improving digital infrastructure and offering on-demand governance and services (Akolawala, 2015).

Bank D is a regional rural bank, whose parent sponsor is Bank B. In other words, Bank D works under the guidance of Bank B; it is a bank which operates in the regional rural areas based on the guidance of the parent bank, though they have autonomy in pursuing their own decisions based on discussions with the parent bank. They follow the protocols outlined by Bank B. Bank D has 500 branches in 16 districts. It implemented the BC-Model in February 2014 and is working on projects launched by government for financial inclusion, such as digitalization of the economy. It serves both the rural and semi-urban population. Additional details related to each case is present in Appendix B.

4.3.3 Introducing the Interview Respondents

Interviews were conducted with multiple stakeholders: the bank manager, an agency representative, two Business Correspondents, and three customers from each bank. The interviews were semi-structured, each completed within 60 min. Table 4 provides details regarding interviewees.

4.3.4 Data Collection

A detailed case study protocolFootnote 6 was developed to guide the data collection and analysis processes. Benbasat et al. (1987) suggest the use of such a protocol to strengthen the study reliability. Qualitative data collection mechanisms including in-depth interviews and existing documentation were used to gather evidence about the success of implemented BC-Models. Interviews were the primary source of evidence, while documentation was used to augment the interview findings. The interview protocol was used to guide the interviewer so that no major issues were overlooked. Usage of such protocols has potential advantages in case study research (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994; Patton, 2002). The defined structure of the protocol assists the achievement of reliability while allowing the researcher freedom to pursue unexpected themes raised by the interviewees.

The interviews started with an open discussion on the current status of the BC-Model, followed by an introduction of the constructs of the conceptual framework and solicitation of the interviewees’ perceptions of their relevance. All constructs of the conceptual framework were investigated across the four cases. The bank manager, BC agency, and BCs were asked questions across all dimensions. They were asked to respond on the first three dimensions from their business’s perspective, and on the satisfaction dimension from the end users’ perspective. Customers were asked questions related to the satisfaction dimension only. The banks at this stage did not have any formal evaluation framework for the success of the BC-Model; the only aspect they measured was profit. Semi-structured interviews enabled the researchers to instantiate existing measures and dimensions of the BC-Model-success framework, while simultaneously obtaining new ideas to enhance the framework. This enabled rich description of the measures and dimensions and identification of any new dimension and measures that are unique to the context of the BC-Model, as presented in Sect. 5.

4.3.5 Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed and maintained in a ‘case database’ (Miles et al., 2014; Yin, 2009). Close linkage between the data, research questions, and conclusions was maintained throughout the analysis. The qualitative data analysis tool NVivo was used to capture, code, and report the findings of the case study. “Codes are tags or labels for assigning units of meaning to the descriptive or inferential information compiled during a study” (Huberman & Miles, 1994, p. 56). The data imported into the NVivo database, was exposed to a hybrid approach, which comprises both deductive and inductive approaches to analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2008). Deductive coding was used to code the case data to the a-priori BC-Model framework, whereas inductive coding enabled obtaining new insights that led to re-specification of the conceptual framework.

In Round 1, an inductive coding approach was used. The interview transcripts were read and any statement that was considered as a measure of the success of the BC-Model was captured at the ‘measures’ node. In Round 2, a deductive coding approach was used. The statements captured in the ‘measures’ node were mapped to the a-priori conceptual framework of the success of the BC-Model. For example, the statement ‘cost savings is essential for the success of the BC-Model’ was mapped to the ‘cost savings’ node. If a measure did not map to any of the a-priori nodes, it was captured in a new node called, ‘interesting insights’. In Round 3, the interesting insights node was revisited to uncover themes that the respondents considered essential to measure the success of the BC-Model. For example, 13 statements referred to monitoring BCs, thus suggesting a new theme, ‘monitoring BCs’. It is these new themes that resulted in the re-specification of the a-priori conceptual framework. In the final Round, Round 4, the nodes of the a-priori conceptual framework were revisited and the content within each node was decomposed into three sub-nodes, ‘relevant’, ‘not relevant’ and ‘neutral’. If a respondent considered the measure important to the success of the BC-Model, it was coded under relevant and if not then under not relevant. If there was no clear opinion on the relevancy of the measure, it was coded under the neutral sub-node. On completing these four rounds the validity of the dimensions and measures of the BC-Model-Success conceptual framework was ascertained.

The appropriateness of the content captured at each node was ascertained through coder-corroboration sessions. Two people were involved in the coding procedure. Detailed corroborations sessions were held to discuss the results and mitigate any misunderstanding during coding.

4.3.6 Case Study Findings

The results across all respondents and banks were amalgamated to derive patterns, a summary of which is presented in Table 6. This process served as a means of the validity of the measures and dimensions of the conceptual framework, while also supporting the identification of new measures or dimensions; an overview is presented below with supporting evidence (quotes) from the case studies. Appendix B presents the detailed case study evidence.

Analysis of the a priori Dimensions

Economic Dimension

The economic dimension was deemed relevant by the respondents of all banks, with the measures providing the respondents with an ability to understand the economic benefits of the BC-Model.

‘Cost Saving’ (Em1) was considered relevant for the success of the BC-Model by all the stakeholders. The manager from Bank D indicated that the BC-model reduced the costs of transactions. “If you go in the bank for any transaction, withdrawal of money or depositing money of doesn’t matter what amount is that, it costs more than 45 rupees per transactions. It includes manpower, technical support etc. If you do these transactions at an ATM, it costs 3.50 -4 rupees. But if you do these transactions at a BC centre, then it costs 1.50 -2 rupees only” (Manager, Bank D).

‘Profitability’ (Em2) was also considered crucial for the success of the BC-Model; “So it [the BC-model] obviously needs to be cost saving and profitable for the bank” (Manager, Bank D). Nonetheless, the BC-Model is not profitable for all banks, and the BC Agency gains poor margins. “Profitability is important but for the BC-Model the agency margins are very bad” (Agency representative, Bank A). Profitability is dependent on reduced costs as well as increased volume of transactions. “If we work well, the model is profitable as we make more transactions” (BC1, Bank A). This relates to the third measure, ‘ability to reach more people’ (Em3) which the respondents view as a crucial measure of success, as the greater the reach the higher the transactions. “It [The BC-Model] should help reach people that bank employees cannot reach” (Manager, Bank D). However, the low volume of reported transactions indicates that it is not currently achieving that goal, suggesting possible improvements to the operations of the model.

In addition to the three measures reported above, the managers of Bank A and B, stressed the need to increase the volume of transactions by providing more services through the BCs. For example, the manager of Bank A stated; “to have a sustainable BC-Model, we need to generate some business through BC also. Our senior management is now focusing on this thing … that BCs need to be educated, in terms of banking products, in terms of you know, they are not there for doing only transactions, they have to do cross sell also, they will have to operate like a small branch in a village” (Manager, Bank A). This brought to light a new measure – ‘ability of BCs to generate business through increased services’ (Em4), included in the revised framework because of its potential to contribute to the economic benefits of the model, (see Sect. 4.3.6 for the re-specified conceptual framework).

Strategic Dimension

The strategic dimension measures were deemed relevant for the success of the BC-Model by respondents across all the banks. The first measure, ‘skilled personnel’ (Sm1), was relevant to all respondents as it enables customers to converse with ease with the banking service providers. According to a BC of Bank C, “Like many, customers of villages are illiterate. They don’t know anything. When they go to bank then anyone says anything to them and they are afraid also. But if they come to us for their work then they tell us everything which they can’t tell in bank.” This clearly suggests that having people who can converse with potential customers, contributes to the success of the BC-Model.

The measure ‘ability of bank to focus on core operations’ (Sm2), was considered relevant by managers of Bank A, C, and D. According to the manager of Bank C, “people who do not have a lot of cash or need some transactions in small amounts, they can work through BCs and they don’t have to come to the branch. When the branch has low crowd, we can focus on better work.” This demonstrates that the BC-Model allows the banks to focus on larger transactions, which are more crucial for the banks to function.

Likewise, ‘Technical competence’ (Sm3) was considered crucial for the success of the model. The banking services have to be provided at geographically sparse locations and this requires competent use of technology for real-time transactions to take place. “Yes [technical competence is crucial for the success of the model]. The technology which we are using is coming from TCS. It is compatible. We are using it for Aadhaar enabled transactions. We will update it also if required in future” (Manager, Bank D). The comments from respondents clearly indicate the need for competent technology for transactions to take place in an efficient manner, which is currently being sourced from technical companies such as TCS (Tata Consultancy Services). This is also reinforced by the fact that technology plays a significant role in the conduct of the model as explained in Sect. 2.

‘Sustainability’ (Sm4) was also considered relevant (e.g., “Yes, the model needs to be sustainable”, Agency representative, Bank D) by respondents of all banks. They clearly indicated that for the BC-Model to be successful, it needs to be perceived as sustainable, otherwise people may not be willing to invest their time for the expansion of the model. Although, according to the respondents, the model is facing a few problems such as technical issues, low volume of transactions, and poor commission rates, they indicated that, if handled successfully and improvements to current operations are made, the model is likely to be sustainable in the long run.

In addition to the above measures, which were derived from the literature, a new measure relevant to the strategic benefits of the model, ‘monitoring BCs’ (Sm5), emerged from the interviews. The managers of Bank A and Bank C strongly communicated the importance of being able to monitor BCs as a crucial aspect to measure the success of the BC-Model; to check their activities so that there is no fraud and also to ensure that the bank is there for support. This clearly shows the amount of time banks need to spend on the model and also the need for the bank and other stakeholders to work together, for the model to be successful. The significance of monitoring BCs can also be understood because of the risk of handling cash inherent in the BC-Model (IFMR, 2013). It is expected that proper monitoring will assist in managing risk and maintaining the reputation of the BC and the bank.

Technological Dimension

Two measures were identified through the literature; ‘access to appropriate technology’ (Tm1) and ‘reduced technological obsolescence’ (Tm2). ‘Access to appropriate technology’ (T1) was considered by respondents as crucial for the success of the BC-Model. Since the BC-Model is a technology based outsourcing model, if technology is not appropriate (i.e., not easy to handle) and not up to date, it will inhibit the success of the model. The manager, agency representative, and BCs across the banks find the technology easy to use and appropriate for the purpose it is designed for. “The machine with the BC, also speaks the transactions that has happened. A lot of customers are illiterate, so they cannot understand what’s written, the machine also speaks, so this helps the customer that the BC cannot cheat the customers” (Manager, Bank C). The manager also affirmed the appropriateness of the technology used in this model in that the device can read the transactions that customer undertake. This enables illiterate people to have confidence in the transactions as they know what is happening to their money.

Like Tm1, all respondents confirmed the relevance of ‘reduced technological obsolescence’ (Tm2) for the success of the BC-Model, especially as they were facing issues because of their technology being obsolete. According to Agency Representative of Bank A, “We have BC points in Chhattisgarh, that person cannot use his machine because of connectivity issues, so if you give him a machine it won’t work”. This indicates that issues in connectivity are making technology obsolete and thereby hampering the work of the BCs, which decreases the number of transactions and impacts both the profitability of the model and employee (which includes bank employees, BCs, as well as agency representative) satisfaction (as indicated later). Through discussions it is evident that the banks rely on external providers for the distribution system, which can at times cause delays. Discussion also revealed that network connectivity too can be a source of delays. The respondents conveyed the significance of having in-house technology for the benefit of the model. Furthermore, access to micro ATMS for easy transaction processing was mentioned by the BCsTherefore, up-to-date technology was of concern and a measure contributing to the success of the BC-Model by all respondents.

Satisfaction Dimension

Similar to the other dimensions, the measures of the satisfaction dimension were also shown to be relevant for the success of the BC-Model. All respondents highlighted the need for the model to provide ‘consistency and dependability of services’ (S1). “As people are benefitting from the BC-Model, they are dependent on the services” (Agency representative, Bank B). The managers state that if we are able to increase people’s dependence on BC-model services, they are likely to use it more than otherwise. ‘Congruence in customer needs and services’ (S2) was also considered very relevant as it is essential for the model to provide services that customers need for transactions to take place. Currently, incongruity between customer needs and services is observed, which is why improvements to the services are suggested. “The customers now, like for cash transactions, there is a limit of 20,000, can’t deposit or withdraw more than this, that limit has to be increased… has to be increased for them to be satisfied” (Manager, Bank B).

‘Accurate information’ (S3) and ‘up-to date information’ (S4), were also considered relevant for the success of the BC-model. “Yes, kiosk is the real-time banking. So, if you do the transaction, it needs [to] reflect immediately on the system” (Manager, Bank D). According to the responses, accurate and up-to-date information induce trust in the operations of the BC-Model, which is essential for the longevity and success of the model. “I am able to get all updated information related to withdrawal and deposit” (Customer, Bank A). In a similar vein, ‘comprehensiveness of services’ (S5), and ‘availability of services’ (SU6) were found to be equally relevant for the success of the BC-Model. “Yes, availability of services at the right time is important” (BC, Bank C). The users appreciate that the services satisfy these measures to a considerable extent, which motivates them to use the services provided by the model. The responses highlight the need of services to adhere to these measures to contribute to satisfaction.

‘Overall satisfaction’ (S7) (which was a satisfaction measure from business perspective) was also considered relevant for the success of the model. As can be seen from Table 6, the relevance for the measure ‘Overall satisfaction’ (SU7) was unanimously agreed to by all respondents across all case studies According to a BC of Bank A, “Yes, 90% of the time [I am satisfied with the model]”. This indicates that satisfaction is important and also in its current state, the model has issues to attend to which can further increase the overall stakeholder satisfaction.

The final two measures, ‘transparency of information’ (SU8) and ‘co-operation and coordination’ (SU9), were reported to be equally relevant for the success of the model. The customers did not contribute to the responses here, unlike other measures in this dimension but all other respondents communicated its relevance for the success of the model. This is because transparency and co-operation are related to people on the service-delivery side than customers who are receiving the services. “Transparency is very much needed. Yes, we are satisfied. There is transparency in every service that is provided by BC-Model” (Agency Representative, Bank C). “We need to work hand in hand with the bank, the creditors, because we are not working independently” (Agency representative, Bank A). These measures were considered valid for smooth communication of requirements (Song et al., 2017) among multiple stakeholders and are also reported to contribute to good outsourcing relationships (Tian et al., 2010), also referred to as a win–win relationship (Bharadwaj & Saxena, 2009).

New Themes Emerging from the Case Data

A case study researcher generally has “less presumptive knowledge of what the variables of interest will be and how they will be measured” (Gable, 1994). Thus, while the BPO literature informed an a-priori framework for measuring BC-Model-success, we were open to new measures. Recall that the interviews, along with questions ascertaining the relevance of a-priori measures, included open-ended questions to identify other factors not identified in the BPO literature, that contribute to the success of the BC-Model.

In addition to the content validity of the measures and dimensions of the a-priori conceptual framework of the BC-Model and reporting new measures (i.e., ‘ability of BCs to generate business through increased services’ (Em4) and ‘monitoring BCs’ (Sm5)) under economic and strategic dimensions, four new themes emerged from analysis of the case data, which did not map to existing dimensions, as shown in Table 5.Footnote 7

‘Salary satisfaction’ was reported as important by the BCs and agency representative of the banks, along with the manager of Bank A. In fact, one BC of Bank C, stressed its significance eight times during the interview. The BCs express dissatisfaction with the current commission structure and mention a mismatch between the effort expended and the pay-off. “My expenditure was Rs15000-20,000 including the rent of the shop, two helpers to take care of the work as I was moving, and right now I spend Rs35000 on them, after that all I earn Rs 15,000 per month which is not sufficient for me. I need a proper salary” (BC, Bank D). They clearly state that unless they are paid well, they will not be motivated to work. This is reinforced by the responses of agency representatives who consider salary satisfaction essential to motivate the employees to do their work. “Then we need to meet the salary etc. for the success of the BC-Model. Then there is logistics. You need to move up the hierarchy, there are team leaders, zonal heads, regional head, state heads, country heads, everybody’s salary compensation has to be taken care of. This is important for employee satisfaction” (Agency representative, Bank A). Adequate compensation for labour has been cited to be important for workers’ rights (Bailey et al., 2018) and a factor to be considered for greater good. Furthermore, salary satisfaction has been cited as an important indicator of employee job satisfaction resulting in motivation and better performance in other studies (Gupta, 2016; Robinson, 2016; Wang, 2012).

The measure—‘Support from higher authority’ was also prominent in the discussions with the BCs of Banks A, B and C, and the manager and agency representative of Bank A. The respondents communicated the need for stakeholders to work in tandem and for the banking officials, to support this initiative, enabling it to grow. The manager of Bank A indicated the significance of the support of government for the success of the BC-Model four times during the interview “We have our own software and program to track these day to day things. The main thing lies in the larger infrastructure, for which the government actually should also help” (Agency representative, Bank A). BCs across banks expressed the need for top management support at least twice during the interviews. “I think Bank support. It is very important for success of BC-Model” (BC, Bank C). Overall, support from higher authorities is required for the success of the BC-Model. Significance of support from higher authorities and governance has been highlighted by prior research for success of outsourcing initiatives (Ali & Green, 2012; Thatcher et al., 2006).

‘Financial awareness’ was another theme cited as crucial for the success of the BC-Model by the managers of Bank A and C, and the BCs of Bank B. “Thirdly [a component of BC-Model-Success], is conducting the financial literacy campaign” (Manager, Bank A). According to the managers, people need to be aware of the merits of saving money, which inspires them to utilize and trust the banking services provided by the BC-Model. Further, ‘empowerment of illiterate people’ was also stated as important by the manager, agency representative, and BCs of Bank B, twice in the interviews. They state that the purpose of the BC-Model is to give power to the unbanked, who are usually illiterate, by letting them have access to finance. According to the manager of Bank B, the BC-Model caters to a wide range of people including those who are hesitant to avail banking services. “The customer is scared of approaching the bank. He might not have been here before and he must be scared of coming over. Those kinds of people are afraid who are illiterate; who don't also understand banking” (Manager, Bank B). The manager then stated that a component of success of the BC-Model, will be empowerment of such customers.

4.3.7 Forming the Revised Conceptual Model

Table 6 provides an overview of the relevance of the measures and dimensions, supported by the multiple case studies. Detailed evidence for each case is present in Appendix B. The new themes have also been listed in Table 6 and been denoted by an asterisk (*). √, indicates the measure was viewed as relevant (or valid) for the success of the BC-Model, and X, indicates the measure is considered not relevant (or not valid, none of the measures were considered not relevant). No clear opinion or response for the measure is indicated by ‘- ‘. N suggests the measure was ‘not applicable’ for the stakeholder of the bank.

The four dimensions (economic, strategic, technological and satisfaction) discussed in Sect. 4.1, were adapted from the BPO literature to the context of the BC-Model, the content was validated through multiple case studies, and was found relevant to the context of the BC-Model. Additionally, there were new themes that emerged. The data suggested six new themes (as explained in Sect. 4.2), of which two mapped as measures to a-priori dimensions (Em4 and SU5), and four did not. This yielded two new dimensions, Employee Satisfaction and Social, and the re-specification of the Satisfaction dimension to ‘Customer Satisfaction’, which are discussed following.

The responses during the interviews clearly indicate the need for employees to be satisfied for the BC-Model to succeed. It is also recognized that there are some needs of employees, which are different from other stakeholders’ of the model, such as customers. This accords with Ee et al. (2013), who state that for outsourcing success, overall stakeholder satisfaction including employees needs to be taken into consideration. This led to the inclusion of the new dimension; Employee Satisfaction, which we define as the perceived employee satisfaction from the BC-Model. While the original ‘satisfaction’ dimension did consider satisfaction from a business perspective, case data pointed to unique themes indicating the need for a separate dimension. The new themes, ‘salary satisfaction’ and ‘support from higher authority’ were considered to be contributing to the satisfaction of the employees and hence were considered apt to measure Employee Satisfaction. Satisfaction of employees was found to be a unique aspect for the success of the BC-Model. Further, recall that we had added two new measures under the ‘stakeholder satisfaction’ dimension, ‘transparency of information’ and ‘co-operation and coordination’ as the BC-Model literature suggested these as significant for the satisfaction of the stakeholders. The case data conveyed that these measures were significant for the satisfaction of employees, and the customers did not have much to do with transparency of information and co-operation and coordination. This was further reinforced with the fact that no responses were obtained for these two measures from customers across the multiple case studies. Though the two measures were initially considered to be a part of the stakeholder satisfaction dimension, given that they do not relate to all stakeholders, but only employees, we included them in the employee satisfaction dimension. Further, we also renamed the ‘satisfaction’ dimension to ‘customer satisfaction’ which we define as perceived customer satisfaction with services of the BC-Model. The measures of this dimension otherwise remained consistent as described earlier. The customer satisfaction dimension measures satisfaction from the target user’s perspective. Thus, the two dimensions, employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction had unique measures intended to measure the satisfaction of employees and customers respectively.

Moreover, the measure ‘overall satisfaction’ (S7) was found to be useful to measure both employee as well as customer satisfaction. This was further evident with both employees as well as customers’ responding to this question confirming its relevance. For employees, overall satisfaction assists in measuring satisfaction from service providers’ perspective, whereas for customers overall satisfaction assists in measuring satisfaction from service recipients’ perspective. This is why we maintained an overarching satisfaction measure for both Employee Satisfaction (ES5) as well as Customer Satisfaction (CS7) dimensions, enabling assessment of satisfaction from both perspectives.

We also propose a social dimension, defined as perceived social benefits from the BC-Model, based on discovery of the themes ‘financial awareness’ and ‘empowerment of illiterate people’. Financial literacy has been widely cited in literature to be an important component of success of financial inclusion (Banerjee et al., 2017; Gwalani & Parkhi, 2014). Further, the respondents also suggest the ability of the BC-Model to empower illiterate people. These themes relate to the social objective of the BC-Model, to bank the unbanked for social cohesion, economic growth and equal growth opportunities (Kolloju, 2014). Considering that the model focusses on social sustainability and the themes also point towards social upliftment, the social dimension to measure the BC-Model-Success is proposed. Thus, whether the model is profitable or not, should it not provide the social benefits, then the purpose of the model is unfulfilled, and it may not be sustainable long term. This is also in accordance with Pal and Herath (2020), who state that for sustainable development, social change is essential.

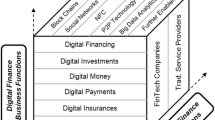

The findings clearly demonstrate the significance of taking technical and socio-technical factors into consideration for the success of IT-enabled BC Model. This is analogous to what has been observed in prior literature measuring the impact of success of information systems (Gable et al., 2008). The new measures, and dimensions were added to re-specify the conceptual framework (Table 7). Potential respondents for the new dimensions and measures are also present in column 3 of Table 7. Based on inclusion of the new dimensions, we also re-define BC-Model-success as “the ability of the model to achieve its intended strategic, economic, technological, and social benefits as well as cater for satisfaction of employees and target users”. The re-specified conceptual framework is depicted in visual form in Fig. 1.

5 Conclusion

This paper reports on a study that aims to conceptualize an emerging BPO initiative, the Business Correspondence (BC) model, which provides banking services to the underprivileged, encouraging sustained economic growth. To do so, we answered two questions: (i) What dimensions characterize the success of the BC-Model? and (ii) What are the measures that anchor these dimensions? A multi-phased approach consisting of systematic literature review and multiple case studies was employed, resulting in a conceptual framework with six dimensions and associated measures. Our findings present the first empirically validated conceptual framework for the evaluation of the success of the BC-Model. Using literature and empirical evidence, we provide a clear definition of what BC-Model-success is and how it can be measured, thereby enabling deeper understanding of the construct. The value of research depends on clear understanding of constructs, as unclear constructs may jeopardize construct validity (Schwab, 1980) and compromise research cumulation; the importance of good constructs for developing theories cannot be overstated (Markus & Saunders, 2007). Theories help in explaining and making sense of the world (Whetten, 1989), whereas constructs help to describe the world (Van de Ven, 2007). It is these constructs which form the basic building blocks of a theory (Weber, 2012). Rather than explaining causality or attempting predictive generalizations, the work presented in this paper achieves understanding of what BC-Model-success is, which coincides with Gregor’s (2006) “theory for analyzing”- theories that focus on ‘what is’.

While we believe the study results are of value, we do acknowledge certain limitations. First, the initial a-priori conceptual model relies on BPO research literature and the limited BC-Model literature. However, we mitigate this issue by applying and validating the conceptual framework in the context of the BC-Model, ascertaining its relevance to the BC-Model context. Second, the data collection was limited to India; other countries such as Brazil, and Kenya, where this model is implemented would be useful to study. Nonetheless, we selected a diverse sample from India to capture many contextual factors influencing the implementation of the BC-Model. Third, we do not collect data from failed cases, i.e., banks that could not implement the BC-Model-successfully. Nonetheless, we collected data from banks where BC-Model was implemented but not performing in an optimal manner. Finally, the new measures and dimensions proposed were not instantiated by all respondents; however, their incidence, along with evidence from the BC-Model literature provided sufficient data to re-specify the conceptual framework.

Regardless, this paper addresses an important research and practice gap. There existed no prior conceptual framework to measure BC-Model-Success. Prior attempts have measured the success of the BC-Model by simply assessing its profitability (see Sect. 2). A more holistic assessment of ‘success’ is required to obtain an accurate view of success. This study conceptualizes BC-Model success holistically with supporting theoretical and empirical input. It resulted in a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) which denotes the multiple dimensions that form BC-Model-Success, together with the measures that can be adapted to assess each dimension (see Table 7). A researcher may select and adapt the components (dimensions and measures) to best suit their research context. Similarly, a practitioner can employ the model to undertake a perception-based evaluation of the success of a BC-Model implementation, adapting the dimensions and measures to the context of the assessment. In example, the measures presented in Table 7 can be used to design an interview protocol or a survey instrument (e.g. a questionnaire based on the Likert scale). Furthermore, the framework can also be used as a reference point by practitioners to evaluate other similar initiatives designed for societal benefit. The framework also contributes to the broader BPO literature; by providing a deeper understanding of the differences between a generic BPO model and a BPO model designed to meet certain goals, in this case financial inclusion.

This work presents various avenues for future work. First, we urge future researchers to test this framework (including quantitative analysis) across other implementations of the BC-Model and report on the relevance of the measures and dimensions. This paper uses a qualitative approach for content validity of the conceptual framework. Future researchers can use enhanced techniques such as Q-sort, weighted average, and advanced quantitative techniques as further validation. The relationship between the dimensions can also be explored to contribute further to BC-Model-success. We propose expanding its use not only in the Indian context, but also the international context. Analytical studies such as those that evaluate the role of each dimension and measure based on characteristics of the bank can also be conducted. For instance, a study could evaluate how the success of the BC-Model differs across economic and strategic dimensions for public versus private sector banks. Once further validated, the conceptual framework can be used to study the antecedents and consequences of BC-Model-success. For example, antecedents such as how does contractual governance impact the success of the BC-Model or consequences such as how the BC-Model contributes towards enhanced financial inclusion can be investigated applying the present framework to conceptualize BC-Model-success. Finally, future researchers may use the conceptual framework presented in this paper to study the success of other similar initiatives.

Given the social significance of the BC-Model in terms of its potential to alleviate financial exclusion, it is important to address the lack of research into what comprises BC-Model-Success. This study has clarified what researchers and BC-Model stakeholders view as success and proposed a conceptual framework for its evaluation.

Notes

Dimensions are the necessary and sufficient attributes/characteristics to describe a concept (MacKenzie et al., 2011), in this case, the success of the BC-Model.

Measures are the items that collectively represent the dimension of a concept (MacKenzie et al., 2011).

Aadhaar is a unique identification number provided to every citizen of India.

Full details pertaining to paper extraction and analysis is not provided here but is available from the first author upon request.

The BC-Model literature included no formal empirical work that evaluated the success of the BC-Model and hence there were no measures that could be adopted, but some literature, especially published consultancy reports was useful to contextualize benefits and issues pertaining to the BC-Model. Consultancy reports can be considered ‘grey’ literature (Benzies et al., 2006); grey literature is defined as public domestic or foreign open source information that is usually available through specific channels and may not enter systems of publication, distribution, or book sellers. Grey literature (like consultancy reports) is recommended to be included for consideration when researching in areas that are emerging and have limited academic literature (Benzies et al., 2006).

A copy of the case protocol can be obtained from the principal author on request.

An overview of case evidence for the new themes can be found in Table 6.

References

Akolawala, T. (2015). Digital India: 10 important initiatives launched by Narendra Modi today. http://www.bgr.in/news/digital-india-10-important-initiatives-launched-by-narendra-modi-today/. Accessed 28th March 2017

Ali, S., & Green, P. (2012). Effective information technology (IT) governance mechanisms: An IT outsourcing perspective. Information Systems Frontiers, 14(2), 179–193.

Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Peria, M. S. M. (2016). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 27, 1–30.

Andrade, A. D., & Doolin, B. (2016). Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. Mis Quarterly, 40(2), 405–416.

Antoninis. M. (2018). A Global Framework to Measure Digital Literacy. UNESCO. http://uis.unesco.org/en/blog/global-framework-measure-digital-literacy. Accessed 23rd April 2020

Arjan, J. K., Egon, B., & Albert, B. (2011). Attributes of communication quality in business process outsourcing relationships: Perspectives from India-based insourcing managers. International Journal of IT/Business Alignment and Governance (IJITBAG), 1(2), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.4018/jitbag.2011010103

Bailey, D. E., Diniz, E. H., Nardi, B. A., Leonardi, P. M., & Sholler, D. (2018). A critical approach to human helping in information systems: Heteromation in the Brazilian correspondent banking system. Information and Organization, 28(3), 111–128.

Banerjee, A., Kumar, K., Philip, D. (2017). Financial Literacy, Awareness and Inclusion.