Abstract

Lack of trust can have a negative influence on consumers’ willingness to use electronic retail (e-tail) platforms especially in countries with weak regulations and poor consumer rights. This paper examined factors that can be employed to build consumer trust and continuance intention to use e-tail platforms in Sub-Saharan Africa. Survey data was collected from 207 respondents and analyzed using structural equation modeling with the PLS software. The results show that information quality, perceived usefulness, hedonic motivation, and perceived risk have a significant influence on consumers’ trust in e-tail platforms. The study contributes to the existing body of knowledge that guides efforts for the implementation of actions in weak institutional contexts characterized by institutional voids such as those experienced in Sub-Saharan African countries. Finally, the study provides insights that can help managers of e-tail platforms to effectively foster the development of trust in their communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Consumer-use platforms such as electronic retail platforms (hereafter, e-tail) provide a medium for various transactions to take place between businesses and consumers. These platforms have long been adopted in developed countries where the necessary institutional conditions underlying their delivery are widely available. However, increasing internet user penetration around the world in the last decade (GSMA 2018) has meant that the use of e-tail websites is also beginning to gain traction in developing countries, particularly in developing Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries. McKinsey estimates that e-commerce spending in SSA is estimated to be $12 billion and projected to reach a revenue of $75 billion per annum by 2025 (McKinsey, 2013). However, at pre-sent, many of these initiatives still end up failing in SSA due to a misunderstanding of the mechanisms that exist in the local context (Asamoah and Andoh-Baidoo, 2018). While there is an extensive body of literature that has investigated factors that influence the intention and usage of e-tail platforms within the Information Systems (IS) literature, these studies have predominantly been conducted in the developed country contexts (Williams et al. 2015) and not within the context of developing countries such as those in SSA.

In existing research, studies on e-commerce research in SSA have emphasized the importance of institutional factors in facilitating e-commerce adoption at firm and user-levels. For example, using the resource-based view perspective, Boateng (2016) highlights the weakness of institutional underpinnings as significant constraints to the realization of e-commerce benefits for small enterprises in Ghana. Similarly, Okoli et al. (2010) echo this position to highlight the notion that strong institutional environments are needed to allow electronic businesses such as e-tail platforms to yield their intended value. Both Boateng (2016) and Okoli et al. (2010) suggest that the characteristically weak institutional environments in SSA countries engender low levels of trust, constituting a significant impediment to the adoption and use of e-tail platforms. It is recognized that trust is essential in facilitating consumer use of online shopping websites (Ayo et al. 2011; Osei and Gbadamsi 2011) and is related to the business performance of online retailers (Lin et al. 2019). Therefore, this study aims to add to the literature by investigating drivers and outcomes of consumer trust in e-tail platforms in the SSA context. This study has the following research objective: To investigate the enablers of consumer trust and continued use of e-tail platforms in the SSA context.

Given the high levels of risk associated with the use of e-tail platforms in SSA, we took a multifaceted approach that encapsulates a range of factors that influence consumer trust in e-tail platforms. To address the research objective, we adapted Kim et al’s (2008) framework to investigate drivers of online trust towards e-tail platforms in the SSA context. The framework conceptualizes the trust-building process to be facilitated by four groups of antecedents, namely: cognition, affect, experience, and personality factors. Cognition-based antecedents refer to capabilities that consumers perceive on the e-tail platform (e.g. information quality, system reliability, security protection, etc.). Affect-based antecedents such as recommendations and word-of-mouth represent third-party influence to use the e-tail platform. Further, experience-based antecedents are related to the degree of familiarity associated with using the e-tail platform. Finally, personality-based antecedents are related to the consumer’s personal characteristics towards using the e-tail platform.

Given the nature of this study, we propose a model where cognitive, affect and personality factors serve as antecedents to consumer trust in e-tail platforms, which in turn leads to the continuance intention to use e-tail platforms. By drawing on this integrated model, we broaden our understanding of the different facets of antecedents that influence consumer trust in e-tail platforms. Further, by investigating continuance intention, we shed further insight on the importance of consumer trust and its subsequent impact on the consumer use behaviors on e-tail platforms. We tested the model using survey data from 207 respondents in Nigeria – a country in SSA. Nigeria provides a suitable case country to situate this study because it fulfills the requirements of the context we aim to provide insight on. Located in SSA, Nigeria’s economy is one the fastest growing in sub-Saharan Africa (IMF 2017). Figures suggest that it is projected to grow from more than 193 million people in 2016 to 392 million in 2050, becoming the world’s third most populous country (UN 2017). Along with the high proportion of potential online consumers, that is, 50% of the entire population (Internet Usage Stats 2018), Nigeria has been regarded as the largest e-commerce hub in Africa (PayPal 2016). Yet, the country is saddled with poor consumer rights and weak policies guiding the use of online services such as e-tail platforms.

This study makes two contributions: first, it contributes to the understanding of antecedents towards trust and continuance intention, which has received limited investigation in the context of e-tail platforms. Hence, the results of this study highlight the necessity to include the consumer’s trust-building process in explaining their continuance intention behavior. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the risk-trust relationship concerning the influence on continuance intention within the SSA context. In addition, our testing of the proposed model using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) structural equation modeling techniques provide robust evidence of how perceived risk and trust are significant determinants of a consumer’s e-commerce behavior. The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows: a theoretical background is presented which covers the theories and concepts that underpin this study in Sect. 2. This is followed by a description of the research model and hypotheses that were tested in Sect. 3. The methods and results of the empirical analysis are presented in Sect. 4 and 5 consecutively. Finally, the manuscript concludes in Sect. 6 with a discussion of the research findings, the theoretical and practical implications of this study, as well as limitations and suggestions for future research.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Continuance Intention on E-tail Platforms

‘Continuance intention’ refers to users’ future intention to use information systems (Bhattacherjee 2001). In the context of electronic retail platforms, it is a conceptually distinct term that represents a post-adoption use behavior (Gao et al. 2015). This study refers to e-tail platform continuance intention as a consumer’s desire to shop again on the internet. It is central to a retailer’s marketing activities because it may cost many times more to attract new customers than retaining existing ones (Gallo 2014). Therefore, understanding continuance intention on e-tail platforms is essential to their effective management which, in turn, can improve the profitability of online retailers. As the purpose of the study is to examine continuance intention as an outcome of online trust, a literature review was conducted of studies focusing on the continuance intention in online shopping services. Table 1 summarizes the findings from the literature review.

As seen from Table 1, some studies have investigated online shopping continuance in conjunction with other post-adoption behaviors such as trust (Shao and Yin 2019) and satisfaction (Lu et al. 2017). With regards to the determinants of continuance, the prior literature has investigated a range of antecedents to understand how electronic retailers might build online shopping continuance intention. For instance, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) related constructs have been examined by Al-Maghrabi et al. (2011) and Mohamed et al. (2014) who found that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use influence online shopping continuance intention. However, Shang and Wu (2017) have more recently demonstrated that this relationship may vary among users and non-users of online platforms. Shao and Yin, (2019) investigated market-driven institutional mechanisms such as payment security, driver certification, feedback mechanism, and surge pricing. Shao and Yin (2019) argue that these institutional factors play an important role in shaping consumer trust in online transactions. Most studies use integrated models that combine a variety of factors (Lu et al. 2017; Mou and Cohen 2017).

Our literature review also identifies that limited studies have examined how to sustain user engagement on electronic platforms in Sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, among online health information seekers. Mou and Cohen (2017) argue that perceptions of system and information quality depend on trust, while trust and satisfaction are important to continued usage intentions. Additionally, Masele and Matama (2020) examined how website design factors and personality characteristics influence trust among individual car buyers in Tanzania. The above-mentioned studies show that the focus on e-tail platforms regarding how to encourage continuance intention is still limited. Thus, there is a need for a more rigorous examination of factors that influence continuance intention on e-tail platforms within the context of African countries. Considering the likelihood that lifestyles and habits differ across online consumers in different countries (Duh 2015), this is a notable omission which this study aims to address.

2.2 Trust in E-tail Platforms

The debate about trust in online environments is often explained in light of the risk the consumer takes in engaging in a particular transaction (Mou et al. 2017). In this study, we investigate trust in e-tail platforms and define it as the degree to which consumers are willing to believe that their expectations will be met during an online transaction (McKnight et al. 2002). Risk, on the other hand, represents the consumer’s subjective belief about the potential for something to go wrong when undertaking online transactions (Garbarino and Strahilevitz 2004; Chandra et al. 2010). Consumers will trust an e-tail platform if they believe that the platform has an obligatory set of rules and policies that protects them from opportunistic online retailers (Pavlou and Gefen 2004). This is beneficial to reduce customers’ concerns about the potential risk of the transactions. Therefore, a lower level of perceived risk represents an important factor in facilitating trust in online services (Chandra et al. 2010).

As a construct, ‘trust’ has been operationalized in a multitude of ways within previous studies. For instance, Liébana-Cabanillas et al. (2014) argue that trust can be integrated into cognitive and behavioral perspectives. Cognitive perspectives relate to benevolence integrity and competence concerns about a third party (McKnight et al. 2002), while a behavioral perspective is defined as the willingness to be vulnerable to actions taken by another party (Mayer et al. 1995). Within the context of online services, Mou and Cohen (2017) argue that there are at least two facets of trust, namely: trust in the website and trust in the online vendor. They argue that both constructs represent significant factors that influence the use of online consumer health services. Further, Venkatesh et al. (2011) argued that trust is a dynamic construct given that it needs to be developed and maintained at different stages of adoption.

Within the e-commerce literature, there is a long-standing debate on how the risk-trust relationship influences the uptake of electronic services such as e-tail platforms (Gefen et al. 2008). On the one hand, risk is viewed as an antecedent to trust. Studies adopting this view (e.g. Chandra et al. 2010) suggest that risk concerns hinder the trust in online services and that the need for consumers to develop trust is predicated on their perceptions of risk. On the other hand, trust is viewed as an antecedent to risk (Shao and Yin 2019). This perspective recognizes the need to facilitate trusting beliefs that reduce the risk concerns among consumers (Mou et al. 2017). Despite the well-established positions concerning the risk-trust relationships, there are still limited studies that have focused on how the risk-trust relationships might be integrated to predict continuance intention (Schaupp and Carter 2010), especially within SSA countries. This study undertakes an exploratory study consisting of cognition, personality, and affect-based antecedents as important drivers for building consumer trust on e-tail platforms within the SSA context. These antecedents are discussed in the next section where the research model and hypotheses are provided.

3 Research Model and Hypotheses Development

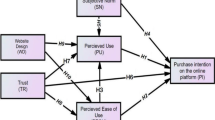

Facilitating trust in online platforms requires a multifaceted approach that considers a range of factors (Kim et al. 2008). This study adapts Kim et al’s (2008) framework because it facilitates the empirical validation of a suitable range of factors that influence the trust-building process and continuance intention within the context of our study. Consequently, the research model used to guide this study is shown in Fig. 1. The model portrays information quality, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, hedonic motivation, perceived risk, and social influence as potential facilitators of consumer trust in e-tail platforms, and consumer trust in e-tail websites as a potential facilitator of continuance intention to use e-tail platforms. It also describes the outcomes of consumer trust in e-tail websites as continuance intention. Alongside this, it tests the influence of three control variables (age, frequency of using e-tail platforms and gender) on the two predicted variables in the model (that is, consumer trust in e-tail websites and continuance intention).

3.1 Perceived Usefulness

Davis (1989, p. 320) defines perceived usefulness as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance”. Like performance expectancy (Venkatesh et al. 2012), it represents the perceived value that users attach to a technology and how that perception affects their decision to adopt and use the technology. In this study, perceived usefulness represents the degree to which using e-tail platforms will provide benefits to users. From a Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) perspective, several studies have broadly documented a positive influence between perceived usefulness on intention (King and He 2006). This positive influence has also been confirmed in consumer-use contexts with studies that have tested the relationship between performance expectancy and behavioral intention (Venkatesh et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2015). However, Venkatesh et al. (2012) have called for studies to account for other key factors that are salient to different research contexts. Moreover, the influence of perceived usefulness on trust remains uncertain in the context of e-tail platforms (Yang et al. 2015). Agag and El-Masry (2017) argue that perceived usefulness positively influences consumers’ trust in the use of online travel websites. It can be anticipated that this result is likely to persist for e-tail platforms. Thus, we hypothesize that perceived usefulness of using e-tail websites plays a significant role in influencing consumers’ behavioral intention:

H1

Perceived usefulness has a positive influence on consumer trust towards e-tail platforms.

3.2 Information Quality

Information quality is concerned with the relevance, accuracy, and the degree to which sufficient information is provided by an information system (Seddon 1997). In this study, we interpret information quality as how relevant, sufficient and accurate the information provided by online retails is on e-tail platforms. In the context of this study, users browse e-tail platforms to purchase a range of goods and services. Given the high levels of distrust associated with online services in Nigeria (Ayo et al. 2011), users need to spend much effort and time on evaluating and scrutinizing information. Therefore, information quality is likely to play a significant role in building trust amongst consumers. If information provided on these sites is not of interest to users or is insufficient, users are likely to doubt the integrity of the retailers to provide quality information to them (Zhou et al. 2016). This is likely to decrease their trust. When information provided on e-tail platforms are accurate and up-to-date, it gives reassurance and a positive perception to consumers about the integrity of the retailers. Extant studies have portrayed how information quality represents a significant antecedent in building trust (e.g. Zahedi and Song 2008; Ponte et al. 2015) including in SSA contexts (e.g., Mou and Cohen 2017). Thus, we propose that:

H2

Information quality has a positive influence on consumer trust towards e-tail platforms.

3.3 Perceived Ease of Use

Perceived ease of use has been defined as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort” (Davis 1989, p. 320). In this study, it is conceptualized as the extent to which consumers find the use of e-tail platforms to be easy. Perceived ease of use is conceptually like effort expectancy which examines the extent to which a technology is easy to understand and use with basic skillsets (Venkatesh et al. 2003; Venkatesh et al. 2012). From a TAM viewpoint, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness represent cognitive factors that have a positive influence on the acceptance of the information system (Davis, 1989). Consequently, if a product or service is easy to use, users are more likely to possess a positive attitude towards its use. Intuitively, the trust-building process is hindered when there are factors that impede easy access and use of the technology/service in question. Previous research has supported the positive and significant relationship between perceived ease of use and consumer trust (Li and Yeh 2010; Agag and El-Masry 2017). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H3

Perceived ease of use has a positive influence on consumer trust towards e-tail platforms.

3.4 Hedonic Motivation

Defined as “the fun or pleasure derived from using a technology” (Venkatesh et al. 2012, p. 161), hedonic motivation has been described as the most important theoretical addition to the UTAUT2 framework (Tamilmani et al. 2019). In this study, it represents the belief that engaging in the purchase of goods and services as facilitated through e-tail platforms will yield fun and enjoyment. A well-designed e-tail platform facilitates consumer trust given that a quality website design attracts customers and gains their attention (Faisal et al. 2016; Masele and Matama 2020). Design aesthetics have been shown to engender trust-building amongst mobile commerce consumers (Li and Yeh 2010) and among unfamiliar vendors (Pengnate and Sarathy 2017) by decreasing the time and effort required by consumers to access and understand information on the website. This, in turn, allows the consumer to experience the website with some fun according to Faisal et al. (2016). Also, Faisal et al’s (2016) study showed that the fun derived from using well-designed online platforms facilitates trust among consumers in relatively higher uncertainty avoidance cultures such as those in SSA. Consequently, we expect that the hedonic motivation derived from using e-tail platforms will positively influence the customers’ trusting beliefs toward e-tail platforms. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H4

Hedonic motivation has a positive influence on consumer trust towards e-tail platforms.

3.5 Perceived Risk

In this study, perceived risk reflects consumers’ concerns regarding the potentially negative consequences of using e-tail platforms resulting from privacy and security concerns. Empirical evidence supports the notion of the negative relationship between risk and trust perceptions and this has been observed for different technological contexts (e.g. Schaupp and Carter 2010). With respect to e-tail transactions, trust is manifested by the subjective belief that online retailers will fulfill an expected service when consumers engage in e-tail transactions (McKnight et al. 2002; Pavlou 2003). Both risk and trust represent two factors that particularly inhibit the adoption of e-services in several African countries (Osei and Gbadamosi, 2011). For example, a study carried by Ipsos (2015) in Nigeria has shown that users exhibit high suspicions of online transactions (such through e-tail websites) due to the high levels of cybercrimes reported within the country. Furthermore, spamming has been recognized as one of the most prevalent activities on the Nigerian Internet landscape, with many Nigerians believing they are susceptible to identity theft when they engage in online transactions (Longe et al. 2007). Consequently, the perceived risk of online platforms thus keeps many consumers from adopting e-tail websites to make purchases. In other words, we would argue that the lack of trust in the prevailing environment has translated to increased perceived risk to engage in online shopping transactions. This study argues that within the SSA context, building consumer trust in e-tail platforms is subject to a lower level of perceived risk regarding the use of e-tail platforms. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H5

Perceived risk of using e-tail platforms has a negative influence on consumer trust towards e-tail platforms.

3.6 Social Influence

Social influence is defined as the perception that people who are important to an individual think a behavior in question should be performed (Ajzen and Fishbein 1977). It refers to the role that socially acceptable norms and practices play in influencing the decisions that individuals make. Previous studies have shown that social influence (such as influences from friends and family) play a dominant role in explaining the use of IT in the African context (Anandarajan et al. 2002). For this study, it is conceptualized as the extent to which consumers perceive that important social referents (e.g., family and friends) believe they should use e-tail platforms. Chaouali et al. (2016) showed that there is a significant positive relationship between social influence and consumers’ initial trust perceptions toward an online vendor. The influence of social influence on consumers’ trust decisions may be viewed from the perspective of the social information processing theory. The social information processing theory proposes that individuals adapt their beliefs to their social context (Salancik and Pfeffer 1978). When individuals believe that significant others think positively about the adoption of a technology, they are more inclined to share the same opinions (Venkatesh et al. 2012). Hence, we hypothesize that:

H6

Social influence has a positive influence on consumer trust towards e-tail platforms.

3.7 Consumer Trust

In this study, consumer trust in e-tail websites is manifested by the subjective belief that online retailers will fulfill an expected service when consumers engage in e-tail transactions (Pavlou 2003). Continuance intention represents consumers’ intention to continue using e-tail platforms. Due to the consumer’s perception of the security and financial risks associated with using e-tail platforms, perceived trust is identified as a salient factor affecting consumers’ continuance intention (Agag and El-Masry, 2017; Shao and Yin 2019). When customers perceive that an e-tail platform provides measures that address uncertainties associated with online-based activities, their likelihood to continue using the platform is increased (McKnight et al., 2002). A significant and positive relationship between trust and continuance intention is supported by a variety of studies (e.g. Hung et al. 2012). Furthermore, most studies in our literature review (see Table 1) have found that trust and satisfaction affect online shopping continuance intention on various platforms (Mohamed et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2015; Shao and Yin 2019). Hence, it is hypothesized that:

H7

Consumer trust toward e-tail platforms has a positive influence on their continuance intention to use e-tail platforms.

4 Methodology

This study is exploratory and adopts a quantitative approach using an online survey approach to test the hypotheses presented in our research model (Fig. 1). A non-probability convenience sampling technique was used to collect data, first by circulating the URL to the questionnaire setup on Qualtrics to a population of students from a university located in south-west Nigeria. We used a student sample because when it comes to mobile advertising, young consumers are a key stakeholder group for online retailers (Scharl et al. 2005). An introduction to the survey, its aims and objectives were provided on the first page of the online survey questionnaire. The respondents were asked to share the URL with their friends and family members. They were informed that participation was voluntary and that their answers were confidential, to be used for research purposes only. One of the major issues with self-reported data is Common Method Bias (CMB). We minimized the risk of CMB in our data using three approaches. First, respondents were also assured of anonymity to ensure that common method bias was minimized (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Second, Harman’s single-factor test was computed based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and revealed the largest variance explained by one factor was 30%. Since the one factor did not account for more than 50% variance, common method bias was deemed unlikely (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Also, CMB is likely if the correlation among latent variables is extremely high (that is, > 0.90) (Pavlou and El Sawy, 2006; Cao et al. 2019). Table 2 shows latent variable correlations showing low correlations between the latent variables in our model. These results imply that CMB is unlikely to be an issue in this study.

All constructs were measured using previously validated and well-documented multi-item scales. The scale for perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, social influence, and hedonic motivation were adapted from Venkatesh et al. (2012). Perceived risk of using e-tail websites and consumer trust in e-tail websites were measured using items adapted from Rana et al. (2015) and Chandra et al. (2010) respectively; while demographic data such as age, gender, education, as well as how long respondents had been using e-tail websites was also collected. The items for all constructs are included in Table 3. The constructs were measured using the seven-point Likert scales ranging from ‘totally disagree’ (1) to ‘totally agree’ (7). This approach provides easy access to respondents practically and quickly. Overall, the survey questionnaire was sent to 404 individuals who use e-tail platforms in Nigeria. Among these, a total of 197 responses were disregarded for the following reasons: (1) the responses were completed within 5 min, whereas the researchers had estimated in a pre-test that the questionnaire would take at least 10 min to complete. Such rapid responses therefore suggest that respondents had completed the questionnaire in a haste and these were not included in the final sample; (2) responses were incomplete and could not be used for the data analysis because questions indicating relevant variables were left unanswered; (3) responses collected from participants outside of Nigeria were removed using the reported IP address of each participant. This ensured only those respondents based in Nigeria remained for the final sample. In total, a sample of 207 valid responses was obtained, indicating a 51% sample response rate.

This sample size satisfies three different criteria for the lower bounds of sample size for PLS-SEM: (1) ten times the largest number of structural paths directed at a particular construct in the inner path model (therefore for the model tested here the sample size threshold for the model in this study would be 70 cases) (Chin, 1998) and (2) according to Anderson and Gerbing (1988), a threshold for any type of SEM is approximately 150 respondents for models where constructs comprise of three or four indicators. (3) Moreover, the sample size also satisfies stricter criteria relevant for variance-based SEM: that is, the recommended ratio of five cases per observed variable (Bentler and Chou 1987). In this case, the sample size threshold would be 125 cases. Most respondents in the sample were males (63.8%) compared to females (36.2%). Participants varied with respect to their level of education as 66.2% reported having attended and obtained a bachelor’s degree, while 16.4% had completed a postgraduate qualification (e.g. master’s and PhD program). Also, most of the respondents in the sample were aged between 18 and 35 years and reported to have been using e-tail websites for at least 2 years or more (67.6%).

5 Analysis and results

The data collected was analyzed using SmartPLS 3.2.7 to perform the Partial Least Square (PLS) (Ringle et al. 2015). PLS allows the modelling of formative and reflective measures in the same model. It also makes fewer assumptions about how the data are distributed compared to more widespread covariance-based SEM techniques (Hair et al. 2016). Using PLS, our research model was analyzed in two stages guided by Hair et al. (2016): (1) the assessment of the measurement model, which includes calculating the reliability and validity of the various constructs in the model and (2) the assessment of the structural model. These two stages represent the process through which conclusions can be drawn concerning the hypothesized paths among the constructs (Ringle et al. 2015).

5.1 Measurement Model

The measurement model for the reflective constructs in our model is examined in terms of construct validity of the measurement scales, indicator reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity. The internal consistency of each construct was also well above the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al. 2016). All loadings as seen in Table 2 were above this recommended threshold. To establish convergent validity, we examined the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The AVE measures the amount of variance captured by the focal construct from its indicators relative to the measurement error (Chin, 1998). MacKenzie et al. (2011) point out that AVE should be greater than 0.5 to ensure constructs account for more than 50% of the variance in its indicators. As can be inferred from Table 2, the reported AVE values of the constructs met this criterion. Finally, we examined the discriminant validity of our measurement model. It represents the extent to which each of the constructs in our model differ from each other (Fornell and Larcker 1981). To assess whether discriminant validity between the constructs in our model had been established, we used two approaches: the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations.

Concerning the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of the AVE was computed for each construct. For adequate discriminant, validity, the diagonal elements should be significantly greater than the off-diagonal elements in the corresponding rows and columns. As can be seen in Table 4, all reflective constructs satisfy this condition; therefore, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was met. Regarding the second criterion, this study applies the HTMT ratio which computes the ratio between the average correlations across constructs measuring different phenomena relative to the average correlations of indicators measuring the same construct. In the guidance provided on how to handle discriminant validity issues in covariance-based SEM, Henseler et al. (2015) have suggested that an HTMT threshold value of 0.9 is adequate. As can be observed in Table 5, all values were lower than Henseler et al’s recommended threshold value. Therefore, we can conclude that discriminant validity was established for our study based on the Fornell-Larcker and HTMT criteria.

5.2 Structural Model

To assess the structural model, we used two main criteria: the level of significance of the path coefficients and the variance explained (R2) (Hair et al. 2016). T-values were computed based on a bootstrapping procedure using 5000 subsamples and the statistical significance of the path coefficients were determined using a two-tailed distribution (Ringle et al. 2015). In total, the results indicate that five out of seven hypotheses in the model were supported. Perceived risk of using e-tail websites (β = -0.228, ρ = 0.000), hedonic motivation (β = 0.173, ρ = 0.006), perceived ease of use (β = 0.128, ρ = 0.049) and information quality (β = 0.333, ρ = 0.000) all had a positive influence on consumer trust to use e-tail websites. Also, consumer trust to use e-tail websites (β = 0.456, ρ = 0.000) had a positive influence on continuance intention. However, contrary to initial predictions, we found no empirical evidence for the direct effect of social influence (β = 0.051, ρ = 0.414) and perceived usefulness (β = 0.072, ρ = 0.336) on consumer trust to use e-tail websites. The results of the structural model present mixed findings on the influence of the control variables on continuance intention and consumer trust to use e-tail websites. With regards to their influence on continuance intention, only frequency (β = 0.159, ρ = 0.017) was significant, while gender (β = -0.127, ρ = 0.018) was the only control variable that significantly influenced consumer trust in e-tail websites. The tested model is depicted in Fig. 2 with path coefficients.

To assess the quality of the model, the coefficient of determination (R2), which represents the amount of variance explained of each endogenous latent variable was computed (Hair et al. 2016). The literature prescribes R2 of 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19 as large, moderate, and weak respectively (Chin 1998). Overall, the model was found to explain 45.9% of variance in consumer trust in e-tail websites and 26.8% in continuance intention. Therefore, we believe that the research model substantially explains variations in consumer trust to use e-tail websites. Finally, we used the standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) to assess the approximate fit for the research model. Defined as the difference between the observed correlation and the model implied correlation matrix, Hu and Bentler (1999) have suggested a criterion for model fit of SRMR < 0.08. The model presented in this study shows an acceptable fit (SRMR = 0.074). The detailed summary of the SEM-PLS assessments is shown in Table 6.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the enablers of consumer trust and the continued use of e-tail platforms. Specifically, we employed an integrated model to explore the drivers of consumer trust in e-tail websites as well as the link to continuance intention. Six factors were hypothesized for building consumer trust towards e-tail websites: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, information quality, hedonic motivation, perceived risk of using e-tail websites, and social influence. Continuance intention was proposed as an outcome of consumer trust towards e-tail websites. The model explained 45.9 percent variance of consumer trust in e-tail websites and 26.8 percent variance of continuance intention. Overall, the results provide support for the proposed model of consumer trust towards e-tail websites. As hypothesized, affect-based antecedents (hedonic motivation), personality-based antecedents (perceived risk), and cognition-based antecedents (perceived ease of use and information quality) antecedents were found to be determinants of consumer trust towards e-tail websites.

With respect to the significant predictors, information quality had the greatest impact on consumer trust towards e-tail websites with a coefficient value of 0.333 (T = 5.341). This suggests that consumer trust toward e-tail websites is highly influenced by the quality of information presented on the website. This result is consistent with the findings of Wang et al. (2020) and Agag and El-Masry (2017) who have examined antecedents to trust towards sharing economy platforms and online travel websites respectively. The finding is consistent with studies conducted in a more developed country context (Zhou et al. 2016). The second most important predictor of consumer trust in e-tail websites was the perceived risk of using e-tail websites with a coefficient value of -0.228 (p < 0.001), suggesting a strong negative influence on consumer trust. This indicates that perceived risk plays an important role in building consumer trust in e-tail websites. Another important result in our analysis is that of the indirect relationship between perceived risk and continuance intention. This indirect relationship is significant (β = -0.104, p < 0.001), suggesting that trust fully mediates the relationship between risk and continuance intention in our model. This finding is consistent with previous Information Systems literature regarding the influence of perceived risk and trust on intention (Li et al. 2007; Chandra et al. 2010).

The results also show that perceived ease of use, with a coefficient value of 0.128, had a significant influence on consumer trust in e-tail websites. This suggests that trust in e-tail websites is also reinforced when they are easy to use because online retailers have simplified the process of buying goods and services on e-tail websites. Also, hedonic motivation was found to positively influence consumer trust toward e-tail websites. In other words, online retailers are more likely to build consumer trust when their websites have been embedded with hedonic features that make them fun and enjoyable to use. This positive relationship between hedonic motivation and consumer trust is also in line with studies that have been conducted in other country contexts (e.g. Li and Yeh 2010). Further, consumer trust is a key indicator for electronic retail providers that seek to influence consumer continuance intention on their e-tail websites. This result reflects the importance of consumer trust in e-tail websites to encourage continuance intention to use e-tail websites.

It is also worth noting the results of the control variables. As portrayed in Table 6; Fig. 2, the influence of three demographic variables (age, gender, and frequency of use) were tested on consumer trust in e-tail websites and continuance intention to use e-tail websites. On the one hand, the results showed that only gender had a significant influence on consumer trust in e-tail websites (β = -0.127*; p < 0.05). This result confirms the results of previous studies that have portrayed gender differences with regard to consumer trust towards information systems (Venkatesh and Morris 2000; Riedl et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2014). On the other hand, only frequency had a significant influence on continuance intention to use e-tail websites (β = 0.159*; p < 0.05). This suggests that an optimal experience is fostered via frequent engagement with e-tail platforms which, in turn, is likely to increase their continued use behaviors.

Two hypotheses were not supported. Results of the structural model assessments show that perceived usefulness and social influence did not significantly influence consumer trust towards e-tail websites. With regards to perceived usefulness, one reason may be that consumer trust-building efforts may not be influenced by the attempts to make e-tail platforms more useful to experienced users. Rather, it is likely that the perceived usefulness of e-tail platforms may influence consumer trust in retailers and not the e-tail platform as portrayed by Thatcher et al. (2013). Also, we argue that the unsupported hypothesis regarding the influence of social influence on consumer trust in e-tail platforms may be underscoring the trepidation that characterizes the use of electronic services in SSA countries. In other words, consumers are less likely to build trust in e-tail platforms based on third-party social influencers. Rather, they are more likely to build trust in e-tail websites via their personal experiences.

6.1 Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study contribute to theory by expanding the literature on online trust through the assessment of its drivers and outcomes concerning e-tail platforms in the SSA context. Using an integrated model, this study provides a more comprehensive view of consumers’ trust-building mechanisms and potential outcomes as it pertains to their continuance intention to use e-tail platforms. Theoretically speaking, the results demonstrate the importance of personality, cognition, and affect-based factors in building consumer trust in e-tail platforms. Also, the influence of trust on continuance intention to use e-tail websites is in alignment with the findings of several previous studies (Gao et al. 2015; Agag and El-Masry 2017; Wang et al. 2020). Past research has recognized the lack of trust that characterizes the use of e-tail platforms in Nigeria (Oghenerukevbe 2008; Ayo et al. 2011), suggesting that the perceived risk of using online platforms for payments can deter many consumers. These results are important because they empirically test relationships that were predominantly developed in the context of developed countries in SSA (McKnight et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2008; Liébana-Cabanillas et al. 2014). Previous studies in the literature have often not adequately explored consumer online trust-building mechanisms in SSA and the relationship between trust and continuance intention. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine trust-building mechanisms and its outcomes concerning continuance intention to use e-tail platforms in the SSA context. We argue that exploring these concepts both empirically and conceptually will provide valuable insights into their distinct roles in the context of e-tail platforms.

With the rapid rise in internet penetration experienced in SSA, the use of e-tail websites and the online retail industry is set to gain rapid prominence (McKinsey 2014). However, the lack of trust can have a negative influence on consumers’ willingness to use e-tail platforms, especially in countries with weak regulations and poor consumer rights. Hence, there is a need to evaluate the factors that predict trust and the continuance intention of e-tail websites in developing countries, such as those in SSA. The ECT model conceptualizes a set of factors underlining users’ intention to continue using IS an after its initial acceptance (Bhattacherjee 2001). For instance, ECT holds that consumers’ intention to repurchase a product or service is determined primarily by their satisfaction with prior use of that product or service (Bhattacherjee 2001; Mohamed et al. 2014). This study contributes to the drivers of continuance intention and our results suggest that trust is a significant driver of consumers online shopping continuance intention.

Further, there is limited research that has employed robust theoretical frameworks to explain trust-building amongst consumers in SSA. Considering this gap in the literature, this study makes a significant theoretical contribution by adding to our understanding of the factors that build consumer trust in e-tail websites in the SSA context. Besides, researchers have emphasized the need to further investigate the theoretical trust-risk relationship with intention and usage in different research contexts (e.g., Gefen et al. 2003; Mou and Cohen 2017). This study responds to this call, exploring the risk-trust relationship influence on the use of e-tail platforms in SSA. Understanding how online retailers might stimulate the trust among consumers in the SSA region should be of interest considering the growing online retail investments in SSA countries (McKinsey 2013). Thus, we make a significant contribution to the literature and provide useful practical insights which are discussed below.

6.2 Practical Implications

Building consumer trust in an environment that is high-risk for online activities such as within the SSA context is a key concern for e-tail retailers. As such, a robust empirical investigation into the antecedents and consequences of consumer trust in e-tail websites was needed. Using an integrated model, this study has investigated the factors leading to consumer trust towards e-tail websites as well as their continuance intention. The results of this study offer some useful implications for e-tail retailers who design e-tail websites and implement tools to improve the utility of online shopping websites in SSA.

An analysis of the model coefficients reveals that information quality and perceived risk of using e-tail websites emerged as the most important factors for building consumer trust towards e-tail websites and, consequently, continuance intention. Therefore, actions should be taken by retailers to improve the quality of information provided on their websites. For example, given the fast-paced nature of retail markets, retailers should ensure information provided on their websites is not obsolete but up to date. Online retailers should also ensure that sufficient information is provided to consumers regarding the process of performing different transactions on their websites. In addition to providing helpful information to consumers, online retailers can encourage consumers to post their product evaluations on the websites. This can help to galvanize trust in the quality of information available on their website.

Based on the results obtained from the structural model assessment, it is also important for online retailers to understand that risk perceptions influence consumer trust. Therefore, it is vital to reduce these concerns providing assurance and confidentiality when users engage with e-tail platforms. For instance, to build consumer trust, e-tail providers can take necessary actions to ensure security on their platforms and provide clear information about these actions on their websites for consumers to read. Also, online retailers should ensure they provide a safe technology environment for consumers to shop online. Information can be provided assuring users of their confidentiality and privacy to ease any psychological concerns when consumers use their websites. Our results also show that hedonic motivation and perceived ease of use are factors that build consumer trust in e-tail websites. Thus, it is suggested that online retailers adopt a range of user-friendly interfaces that makes it easier for consumers to access their website. For instance, it is widely recognized that most internet access in Nigeria occurs via mobile/smartphones (Schoentgen and Gille 2017). Hence, online retailers could provide mobile-friendly designs that allow consumers to engage with goods and services on their websites as they would if they were using other devices such a computer/laptop, for example. Finally, we suggest online retailers adopt creative interface designs that make their websites fun to visit. Our results show that such efforts improve hedonic motivation which is likely to build consumer trust.

6.3 Limitations and Scope for Future Research

This study has some limitations which should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the survey used in the study was conducted using online-based forms and employed a non-random convenience sample because obtaining a larger sample using a random sampling method would be costly. As a result, the resulting sample for the study was limited to only respondents who had internet access. Thus, to enhance generalizability in a context like Nigeria, future research could utilize the use of paper-based questionnaires to augment online versions. Second, the relationships between factors/variables were assessed using cross-sectional data, resulting in findings that apply to a single point in time. However, perceptions change over time as individuals gain experience (Venkatesh et al. 2012), and, likely, perceived risk and trust factors may also be influenced over time. As a result, further studies may enhance our understanding by conceptualizing trust at different points in time (e.g. Mou and Cohen 2017). Also, the results of our control variables provide interesting insights for future studies on this topic. For instance, studies can extend this work by investigating how the relationship between the variables used in this study might vary across different age groups and how gender differences might play a role. Also, we did not include experience-based constructs from Kim et al. (2008) in our analysis because the use of e-tail platforms was still at a nascent stage. Consequently, future research may extend our work by comparing the results between users in urban and rural contexts of SSA. Such a line of inquiry will draw attention to the digital divide phenomenon that often exists in developing country contexts.

References

Agag, G. M., & El-Masry, A. A. (2017). Why do consumers trust online travel websites? Drivers and outcomes of consumer trust toward online travel websites. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 347–369.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918.

Al-Maghrabi, T., Dennis, C., & Vaux Halliday, S. (2011). Antecedents of continuance intentions towards e-shopping: the case of Saudi Arabia. Journal of enterprise information management, 24(1), 85–111.

Anandarajan, M., Igbaria, M., & Anakwe, U. P. (2002). IT acceptance in a less-developed country: a motivational factor perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 22(1), 47–65.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Asamoah, D., & Andoh-Baidoo, F. K. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of extent of ERP systems implementation in the Sub-Saharan Africa context: A panoptic perspective. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 42(22), 581–601.

Ayo, C. K., Adewoye, J. O., & Oni, A. A. (2011). Business-to-consumer e-commerce in Nigeria: Prospects and challenges. African Journal of Business Management, 5(13), 5109–5117.

Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Decision Support Systems, 32(2), 201–214.

Boateng, R. (2016). Resources, electronic-commerce capabilities and electronic-commerce benefits: Conceptualizing the links. Information Technology for Development, 22(2), 242–264.

Cao, X., Khan, A. N., Ali, A., & Khan, N. A. (2019). Consequences of cyberbullying and social overload while using SNSs: A study of users’ discontinuous usage behavior in SNSs. Information Systems Frontiers, 1–14.

Chandra, S., Srivastava, S. C., & Theng, Y. L. (2010). Evaluating the role of trust in consumer adoption of mobile payment systems: An empirical analysis. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 27(1), 561–588.

Chaouali, W., Yahia, I. B., & Souiden, N. (2016). The interplay of counter-conformity motivation, social influence, and trust in customers’ intention to adopt Internet banking services: The case of an emerging country. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 209–218.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 319–340.

Duh, H. (2015). Testing three materialism life-course theories in South Africa. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 10 No(4), 747–764.

Faisal, C. N., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M., Fernandez-Lanvin, D., & de Andres-Suarez, J. (2016). Web design attributes in building user trust, satisfaction, and loyalty for a high uncertainty avoidance culture. IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems, 47(6), 847–859.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 382–388.

Gallo, A. (2014). The Value of Keeping the Right Customers. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/10/the-value-of-keeping-the-right-customers. Accessed 16 Nov 2019.

Gao, L., Waechter, K. A., & Bai, X. (2015). Understanding consumers’ continuance intention towards mobile purchase: A theoretical framework and empirical study–A case of China. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 249–262.

Garbarino, E., & Strahilevitz, M. (2004). Gender differences in the perceived risk of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation. Journal of Business Research, 57(7), 768–775.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90.

Gefen, D., Benbasat, I., & Pavlou, P. (2008). A research agenda for trust in online environments. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 275–286.

GSMA (2018). The Mobile Money 2018. Available from: https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/The-Mobile-Economy-Global-2018.pdf. Accessed: 16/07/2018.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Huang, L., Ba, S., & Lu, X. (2014). Building online trust in a culture of confucianism: The impact of process flexibility and perceived control. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS), 5(1), 1–23.

Hung, M. C., Yang, S. T., & Hsieh, T. C. (2012). An examination of the determinants of mobile shopping continuance. International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 10(1), 29–37.

IMF (2017). Sub-Saharan Africa, Fiscal adjustment and Economic Diversification. Available from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/SSA/Issues/2017/10/19/sreo1017. Accessed 18 Sept 2018.

Internet Usage Stats (2018). Internet Users in the world by regions. Available from: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm. Accessed 15 Oct 2018.

Ipsos (2015). PayPal cross-border consumer research 2015. Available from: https://www.paypalobjects.com/digitalassets/c/website/marketing/global/pages/jobs/paypal-insights-2015-global-report-appendix-added.pdf. Accessed 08/05/2018.

Kim, D. J., Ferrin, D. L., & Rao, H. R. (2008). A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decision Support Systems, 44(2), 544–564.

King, W. R., & He, J. (2006). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 43(6), 740–755.

Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Muñoz-Leiva, F. (2014). Antecedents of the adoption of the new mobile payment systems: The moderating effect of age. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 464–478.

Li, R., Kim, J. J., & Park, J. S. (2007). The effects of internet shoppers’ trust on their purchasing intention in China. Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management, 4(3), 269–286.

Li, Y. M., & Yeh, Y. S. (2010). Increasing trust in mobile commerce through design aesthetics. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(4), 673–684.

Lin, X., Wang, X., & Hajli, N. (2019). Building E-commerce satisfaction and boosting sales: The role of social commerce trust and its antecedents. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 23(3), 328–363.

Longe, O. B., Onifade, O. F., Chiemeke, S. C., & Longe, F. A. (2007). User acceptance of Web-marketing in Nigeria: Significance of factors. Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Business & Economics. Piraeus, Greece.

Lu, J., Wei, J., Yu, C. S., & Liu, C. (2017). How do post-usage factors and espoused cultural values impact mobile payment continuation? Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(2), 140–164.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 293–334.

Masele, J. J., & Matama, R. (2020). Individual consumers’ trust in B2C automobile e-commerce in Tanzania: Assessment of the influence of web design and consumer personality. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 86(1), e12115.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

McKinsey. (2013). Lions go digital: The Internet’s transformative potential in Africa. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/w4z3l5r. Accessed: 24/02/2020.

McKinsey. (2014). Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering inclusive growth in Africa’s largest economy. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/nigerias-renewal-delivering-inclusive-growth. Accessed 30 Apr 2018.

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 334–359.

Mohamed, N., Hussein, R., Hidayah Ahmad Zamzuri, N., & Haghshenas, H. (2014). Insights into individual’s online shopping continuance intention. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 114(9), 1453–1476.

Mou, J., & Cohen, J. F. (2017). Trust and online consumer health service success: A longitudinal study. Information Development, 33(2), 169–189.

Mou, J., Shin, D. H., & Cohen, J. F. (2017). Trust and risk in consumer acceptance of e-services. Electronic Commerce Research, 17(2), 255–288.

Oghenerukevbe, E. A. (2008). Perception of Security Indicators in Online Banking Sites in Nigeria. Available at SSRN 1290522.

Okoli, C., Mbarika, V. W., & McCoy, S. (2010). The effects of infrastructure and policy on e-business in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. European Journal of Information Systems, 19(1), 5–20.

Osei, C., & Gbadamosi, A. (2011). Re-branding Africa. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 29(3), 284–304.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. International journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101–134.

Pavlou, P. A., & El Sawy, O. A. (2006). From IT leveraging competence to competitive advantage in turbulent environments: The case of new product development. Information Systems Research, 17(3), 198–227.

Pavlou, P. A., & Gefen, D. (2004). Building effective online marketplaces with institution-based trust. Information Systems Research, 15(1), 37–59.

PayPal. (2016). PayPal Ranks Nigeria 3rd in Mobile Shopping. Available from: http://investorsking.com/paypal-ranks-nigeria-3rd-in-mobile-shopping/. Accessed 30 Aug 2017.

Pengnate, S. F., & Sarathy, R. (2017). An experimental investigation of the influence of website emotional design features on trust in unfamiliar online vendors. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 49–60.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Ponte, E. B., Carvajal-Trujillo, E., & Escobar-Rodríguez, T. (2015). Influence of Trust and Perceived Value on the Intention to Purchase Travel Online: Integrating the Effects of Assurance on Trust Antecedents. Tourism Management, 47, 286–302.

Rana, N. P., Dwivedi, Y. K., Williams, M. D., & Weerakkody, V. (2015). Investigating success of an e-government initiative: validation of an integrated IS success model. Information Systems Frontiers, 17(1), 127–142.

Riedl, R., Hubert, M., & Kenning, P. (2010). Are there neural gender differences in online trust? An fMRI study on the perceived trustworthiness of eBay offers. MIS Quarterly, 34(2), 397–428.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253.

Scharl, A., Dickinger, A., & Murphy, J. (2005). Diffusion and success factors of mobile marketing. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 4(2), 159–173.

Schaupp, L. C., & Carter, L. (2010). The impact of trust, risk and optimism bias on E-file adoption. Information Systems Frontiers, 12(3), 299–309.

Schoentgen, A., & Gille, L. (2017). Valuation of telecom investments in sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy, 41(7–8), 537–554.

Seddon, P. B. (1997). A respecification and extension of the DeLone and McLean model of IS success. Information Systems Research, 8(3), 240–253.

Shao, Z., & Yin, H. (2019). Building customers’ trust in the ridesharing platform with institutional mechanisms: An empirical study in China. Internet Research, 29(5), 1040–1063.

Shang, D., & Wu, W. (2017). Understanding mobile shopping consumers’ continuance intention. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(1), 213–227.

Tamilmani, K., Rana, N. P., Prakasam, N., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2019). The battle of brain vs. heart: a literature review and meta-analysis of “hedonic motivation” use in UTAUT2. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 222–235.

Thatcher, J. B., Carter, M., Li, X., & Rong, G. (2013). A Classification and Investigation of Trustees in B-to-C e-Commerce: General vs. Specific Trust. Communications of the Association for Information System, 32(4), 107–134.

UN. (2017). World Population prospects: key findings and advance tables. Available from: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf. Accessed: 06/09/2018.

Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. G. (2000). Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 115–139.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., Chan, F. K., Hu, P. J. H., & Brown, S. A. (2011). Extending the two-stage information systems continuance model: Incorporating UTAUT predictors and the role of context. Information Systems Journal, 21(6), 527–555.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178.

Wang, Y., Asaad, Y., & Filieri, R. (2020). What Makes Hosts Trust Airbnb? Antecedents of Hosts’ Trust toward Airbnb and Its Impact on Continuance Intention. Journal of Travel Research, 59(4), 686–703.

Williams, M. D., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2015). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): a literature review. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 28(3), 443–488.

Yang, Q., Pang, C., Liu, L., Yen, D. C., & Tarn, J. M. (2015). Exploring consumer perceived risk and trust for online payments: An empirical study in China’s younger generation. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 9–24.

Zahedi, F. M., & Song, J. (2008). Dynamics of trust revision: Using health infomediaries. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 225–248.

Zhou, T., Lu, Y., & Wang, B. (2016). Examining online consumers’ initial trust building from an elaboration likelihood model perspective. Information Systems Frontiers, 18(2), 265–275.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Odusanya, K., Aluko, O. & Lal, B. Building Consumers’ Trust in Electronic Retail Platforms in the Sub-Saharan Context: an exploratory study on Drivers and Impact on Continuance Intention. Inf Syst Front 24, 377–391 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10043-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10043-2