Abstract

This study aims to build on the understanding of social commerce in the emerging markets and how it influences online community engagement. The conceptual model was proposed using theories including the social support theory, the trust theory, the social presence theory, the flow theory and the service-dominant logic theory. Using Facebook online community, the data were collected from 400 respondents from Jordan and analysed using AMOS based structural equation modelling. Results revealed that social commerce constructs positively influence social support, community members’ trust and social presence. Furthermore, it was found that social support and social presence positively affect community members’ trust. We also found that community members’ trust positively influence flow whereas both community members’ trust and flow positively influence community engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social commerce paradigm is considered as a part of electronic commerce (e-commerce) (Stephen and Toubia 2010) and has emerged as an extensive growth of social networking sites (SNSs). Therefore, social commerce is considered as a main tool for electronic shoppers (e-shoppers) to share their experience via peer interactions (Liang and Turban 2011). Social commerce facilitates customers’ information sharing, extending their recommendations (Chen and Shen 2015; Liang and Turban 2011; Mirkovski et al. 2019; Wang and Zhang 2012; Zheng et al. 2017) and getting the best prices. Thus, social commerce is a combination of e-commerce and SNSs that intends to enhance shoppers’ experience online (Marsden 2010). Lal (2017) asserts that social commerce is the newest form to combine communication technology and information. Thus, social commerce creates a competitive advantage for companies that employ SNSs for conducting business online. The advancement in technology within social media encouraged customers to interact with their peers (Liang and Turban 2011) and hence invites them to be an essential part of the social community.

Although the research on social commerce constructs has drawn the attention of research scholars, the extant literature on social commerce constructs investigated the impact of social commerce constructs (directly and/or indirectly) on social support, flow, social presence, social trust, and customer engagement (Li 2017; Triantafillidou and Siomkos 2018; Zhang et al. 2017). For example, Zhang et al. (2017) investigated the impact of social commerce dimensions on customer engagement. Similarly, Li (2017) reported the positive relationship between social commerce dimensions and social support. In a similar vein, Li (2017) asserts the significant correlation between social commerce constructs and social presence. Likewise, Triantafillidou and Siomkos (2018) revealed the positive influence of flow on behavioural engagement. Moreover, within the e-commerce context, trust is considered to be a vital issue that prevents customers from buying online. Lack of trust facilitates customers’ hesitation to conduct the online purchases or even to avoid them altogether (Asim et al. 2019; Gefen 2000; Jones and Leonard 2008). Accordingly, extant literature on social commerce posits the importance of community members’ trust in different SNSs as a tool to enhance their online purchase, to create and share their stories on SNSs. Therefore, customers have many reasons for distrusting firms using social commerce on SNSs. For example, users’ concerns regarding the quality of information that social commerce firms provide for them over SNSs make them trust other consumers more than they trust the firm itself (Mutz 2005). Therefore, social commerce firms can benefit from building and enhancing social trust among users (Jarvenpaa et al. 2000). Thus, community members’ trust within social commerce becomes a significant area (Kim 2011). Previous research (e.g. Alalwan et al. 2019; Kim and Park 2013) assert the positive relationship between social commerce constructs and social trust. For instance, Vohra and Bhardwaj (2019) find a positive relationship between community trust and engagement. Similarly, Zhou (2017) posits the significant relationship between social support dimensions (informational support and emotional support) and trust. Furthermore, the author posits the significant association between trust and flow.

However, we noticed that none of the existing research within the context of social media commerce has investigated the interrelationships between social commerce constructs, social support, flow, social presence, social trust and community engagement within a single model. We believe that combining the constructs from the existing research in one single model will enhance researchers’ understanding of the nature of the relationships among them. Thus, we intend to examine how the dimensions of social commerce constructs (ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities) influence social support dimensions (information support and emotional support) and social presence. Furthermore, the current study examines the impact of social commerce constructs’ dimensions, social support dimensions and social presence on community members’ trust, which in turn impacts flow and online community engagement dimensions (cognitive, affective and behavioural). Furthermore, we investigate the impact of flow on online community engagement dimensions. The current study, to the best of our knowledge, establishes the first attempt to validate the causal relationships between the various constructs from the proposed research model.

Recently, social commerce witnessed tremendous growth across the world as well as in the Middle East countries, which encouraged many local firms to join SNSs (Alalwan et al. 2017a, 2019; Algharabat et al. 2020; Kapoor et al. 2018). Smatinsights (2020) report shows that by the end of 2019, number of social media users reached 3.5 billion worldwide. Furthermore, according to the report, (i) almost 55% of online shoppers conducted their shopping via one of three main social commerce platforms i.e. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. (ii) 87% of social commerce shoppers rely on social media to aid their shopping decisions, (iii) 30% of consumers would make their purchase decisions directly via social commerce platforms. Thus, we decided to conduct this study in emerging markets such as Middle East – particularly in the context of Jordan. According to Entrepreneur (2020), e-commerce in MENA region is expected to reach US$ 69 billion by the end of 2020, and hence to be the second biggest market in e-commerce. Furthermore, Napoleoncat (2020) posits that number of Facebook users in Jordan reached more than 5.8 million with 42.1% women and 57.9% men. These number of Facebook users represent 55.8% of the entire Jordanian population. Moreover, the Jordanian authority announced that more than 243 million dollars were spent by Jordanian customers on e-commerce via websites and social media platforms (Alrai Newspaper 2019). This makes the current study of significant importance to examine social commerce within emerging market such as Jordan in which social commerce considered as a promising emerging market. Therefore, the current study aims to respond to the following research questions:

-

1.

How does the notion of a social commerce construct influence social support, social presence and community members’ trust?

-

2.

How does social support and social presence influence community members’ trust?

-

3.

How does community members’ trust influence flow (i.e., consumer feelings which produced as a sense of immersion due to their interaction with SNSs platforms)?

-

4.

How does community members’ trust and flow influence community engagement?

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature around theoretical background of this research. Section 3 present the underpinning theories and proposes a research model based on them. Further, Section 4 discusses the methodology of this research followed by results in Section 5. Section 6 presents discussion in the backdrop of existing literature. Finally, the paper is concluded in Section 7.

2 Literature Review

This section explains the key constructs used in this study, as we detail constructs being studied in this research (social commerce constructs, social media engagement, social support, social presence, community member trust and flow), their definitions and measurement inherited from the extant literature. Table 1 provides a summary of the various studies focused on the proposed constructs and their dimensions and context. Table 1 shows that social commerce constructs, social support, community member trust, social presence, flow, and community engagement were investigated within different countries using different SNSs. Therefore, there is a need to study the causal relationships between the proposed constructs where we have lack of understanding on how social commerce constructs might be linked with other constructs in the context of emerging market such as Jordan.

2.1 Social Commerce Constructs

Social commerce as a subset of e-commerce allows customers to build and share their content over SNSs (Huang and Benyoucef 2013). Extant literature posits that social commerce over SNSs provides customers with different channels to, socially, generate their content and to share their information with others (Huang and Benyoucef 2013). Thus, social commerce, facilitated by SNSs, aims to enhance social interaction and the online shopping experience (Marsden 2010). Therefore, social commerce motivates customers’ value co-creation (Curty and Zhang 2013). Accordingly, social commerce is a combination of Internet and social media and aims to enhance people’s participation in marketing and the sale of different products within online communities (Stephen and Toubia 2010). Firms that use social commerce offer their customers a diverse range of goods and services (e.g. electronics, grocery and event tickets) and collaborate with different SNSs (Stephen and Toubia 2010). Therefore, consumers play an important role in marketing the firms’ dealings through SNSs because customers share their shopping experience and provide others with more information via their comments. Thus, previous studies (e.g. Alalwan et al. 2019; Chen and Shen 2015; Hajli 2015; Liang and Turban 2011; Sarker et al. 2020; Sheikh et al. 2019) on social commerce constructs assert that recommendations and referrals, ratings and reviews and forums and communities are the three main dimensions of social commerce constructs that help consumers to be content creators and thus help other consumers to make their buying decisions. Therefore, the ability of social commerce to allow users to participate in online communities facilitates sharing their experience and spreading word-of-mouth regarding firms’ goods and services (Alalwan et al. 2019; Alalwan et al. 2017a; Chen and Shen 2015; Füller et al. 2006; Hajli 2015).

2.2 Social Media Engagement

Recently, scholarly marketing literature on customer engagement is growing significantly (Alalwan et al. 2020; Algharabat et al. 2018; Dessart 2017; Dessart et al. 2016; Preuveneers et al. 2020; Trivedi et al. 2018). Furthermore, there is an agreement within extant research on the definition of customer engagement as a psychological state of interacting with an object (Hollebeek et al. 2016). Moreover, there is an agreement among previous research on the main dimensions of customer engagement, as this notion constitutes of cognitive, affective and behavioural dimensions (Algharabat 2018; Algharabat et al. 2018, 2020; Calder et al. 2009; Dessart 2017; Dessart et al. 2016; Hollebeek et al. 2014; Hollebeek 2011a, b). Brodie et al. (2013) assert that social media engagement is derived from customer engagement. The authors assert that social media engagement is a context-specific incidence of customer engagement which should be investigated due to the variation in the notion of engagement through online media (Geissinger and Laurell 2016).

According to Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), social media permits users to create and exchange content. Therefore, SNSs such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Flickr and blogs are considered parts of social media. Hence, social media features facilitate consumers’ interaction with other consumers and with the brands (online brand community) and thus facilitate customer engagement (Brodie et al. 2013; Zaglia 2013). Dessart (2017) defines social media engagement from a positive point of view, as consumers’ dispositions regarding communities and brands via different levels of affective, cognitive and behavioural displays. Furthermore, the author asserts that social media engagement consists of two dimensions: (i) community engagement which reflects consumer interaction with other consumers in a particular online community and (ii) brand engagement which reflects consumer interaction with the focal brand (Brodie et al. 2013; Dessart 2017). The author claims that community engagement has a positive impact on brand engagement (Wirtz et al. 2013). The author explains that both community engagement and brand engagement are multidimensional constructs each consisting of three dimensions i.e. cognitive, affective and behavioural. Therefore, we will focus on community engagement as part of social engagement. We particularly focus on this area due to the lack of research (Dessart 2017) on community engagement.

2.3 Social Support

The notion of social support is derived from social support theory (Lakey and Cohen 2000), which posits that social relationship affects individuals’ cognition, emotion and behaviour (Lakey and Cohen 2000). Within the context of social commerce, social support is related to both informational and emotional support that customers get from SNSs or online communities (Hajli 2014; Liang et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2015; Romaniuk 2012; Sheikh et al. 2019; Yan and Tan 2014). Information support helps customers to solve their problems or to generate solutions via peer advice, suggestions, guidance, recommendations and useful knowledge, experience and information (Chen and Shen 2015; Liang et al. 2011). Emotional support is related to another type of support among peers that centred on expressions such as; empathy, care, concerns and understanding (Liang et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2015). Therefore, emotional support enhances peer interaction with others and as a result develops bonds among online community (Lin et al. 2015; Molinillo et al. 2019; Oh et al. 2014). Thus, social support, with its dimensions, is expected to add value for both SNSs members and online communities.

2.4 Social Presence

The notion of social presence is derived from social presence theory. Short et al. (1976) defined it as the existence of the human element in interactions, which reflect human interpersonal relationships. Within SNSs, scholars conceptualised social presence as: (i) a unidimensional construct and (ii) a multi-dimensional construct. For instance, scholars in the information system field (e.g., Gefen and Straub 2003; Kumar and Benbasat 2002), in particular e-commerce, depend on Short et al.’s (1976) and Biocca et al.’s (2001, 2003) definition of conceptualising social presence as users’ perception of a medium to be sociable, sensitive, warm, and personal (Rice and Case 1983). On the other hand, conceptualising social presence as a multidimensional construct often determines customers’ virtual experience from different aspects (Tu 2002; Shen and Khalifa 2008; Shen et al. 2010). Shen and Khalifa (2008, p. 729) defined social presence as individual awareness, affective and cognitive engagement of other people in computer-mediated social spaces.

Within the context of online learning communities, Caspi and Blau (2008) specify three dimensions of social presence i.e. a medium’s impersonality (perception of others and medium as interaction enabling the perception of other), self-projection, and social identification. Tu (2002) identified three dimensions for social presence such as social context, interactivity and online communication. Within the context of social commerce, Lu et al. (2016) relied on Caspi and Blau’s (2008) study to conceptualise social presence based on three dimensions (i.e. awareness, perception of others, and interaction with sellers). Similarly, Shen et al. (2010) identified three dimensions (i.e. awareness, cognitive social presence and affective social presence) for social presence. Chang and Hsu (2016) adapted Shen and Khalifa’s (2008) scale to measure social presence with its three-dimensions. Han et al. (2016) relied on Gefen and Straub’s (2003) unidimensional scale to measure social presence within a corporate SNS.

Previous research (e.g., Gao et al. 2017; Lim et al. 2015; Obeidat et al. 2020) employed a unidimensional scale to investigate social presence on a SNS based on Khalifa and Shen’s (2004) and Steuer’s (1992) scale. Han et al. (2016) investigated social presence in a SNS and conceptualised social presence as a unidimensional construct based on Karahanna and Straub’s (1999) scale. Thus, it could be noticed that the significance of social presence appears across various studies in the field of SNSs because of its ability to enhance social interaction and communication between the users of a particular SNS or users and firms (Cui et al. 2013; Tu 2002; Xiao et al. 2019a; Yu and Vahidov 2019).

2.5 Community Members Trust

Community members’ trust appears well in SNSs literature (Sherchan et al. 2013; Ziegler and Lausen 2005; Golbeck 2005). However, this paper focuses on one type of social trust among community members, namely, context trust (Golbeck 2005), in particular, users’ trust with other users in SNSs (Agarwal and Bharadwaj 2011). Community members’ trust is related to a particular type of trust which is formulated as a result of community members’ perception regarding other consumers’ benevolence within SNSs. Extant literature (e.g. Rothstein and Uslaner 2005; You 2012) linked community members’ trust with SNSs users’ trustworthiness. The notion of community member trust is considered as one of the main tools which community members relied on to achieve certain benefits such as reducing transaction costs, increasing members’ ability to shop online, and reducing risks (Aljifri et al. 2003; Grazioli and Jarvenpaa 2000; Mutz 2005).

Söllner et al. (2016) define trust in community members as a member’s willingness to depend on other members’ actions, reviews and thus to build decisions regarding their concerns on particular SNS platforms. Pan et al. (2007) assert that community members can take advantage of other members by sharing information, which facilitates their decisions. According to the trust transfer theory, this type of trust between community members can be derived as a result of the mutual associations among the same community members (Alalwan et al. 2019; Stewart 2003).

2.6 Flow

Within social commerce, flow experience is used as a basis of percussive experience (Ding et al. 2010). Therefore, previous research defines flow experience based on a psychological state which facilitates consumers’ involvement within a particular stimulus, and as a result it reflects the consumer’s feelings when they are fully absorbed with the experience (Csikszentmihalyi 1977; Gao and Bai 2014). Thus, flow experience is considered a significant element (Gao and Bai 2014; Hoffman and Novak 1996; Hsu et al. 2011) within SNSs. In particular, SNSs heavily depend on consumer interactions with others. This type of interaction generates a sense of immersion and thus prompts consumers’ flow experience (Mollen and Wilson 2010; Teng et al. 2012).

3 Theoretical Background and Proposed Research Model

In order to build our proposed research model, we relied on different theories, such as social support theory (Liang et al. 2011), social presence theory (Labrecque 2014; Gefen and Straub 2003; Rubin et al. 1985), community trust theory (Cummings and Bromiley 1996; Chen et al. 2009; Luo 2005), flow theory (Zhang et al. 2014) and service-dominant (S-D) logic theory (Vargo and Lusch 2008; Lusch and Vargo 2010). The justification of adopting every theory within the context of social commerce has been provided along the description of these theories below. Moreover, using Web 2.0 and social commerce help delivering e-commerce transactions and activities via social networks environment (Alalwan et al. 2019). We decided to adopt the notion of social commerce (Pagani and Mirab 2011; 2012) due to the features of social commerce platforms to help customers to share their information with friends about different products and services. Accordingly, social commerce constructs consist of three dimensions (recommendations and referrals, ratings and reviews and forums and communities). More about these theories are explained below with more emphasis on the reasons of adopting them.

3.1 Social Support Theory

We adopted social support theory (Lakey and Cohen 2000) in the current study due to its ability to impact users’ cognition, emotion and behaviour (Lakey and Cohen 2000). Social support is related to users’ information and action that creates consumers’ feelings of being loved, cared of and valued (Rozzell et al. 2014). Furthermore, social support reflects individual experience of being helped by others within a particular social group. Thus, social support facilitates exchange feelings and understanding between users of a particular SNSs. Extant literature (e.g. Hajli 2014; Liang et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2015; Sheikh et al. 2019; Yan and Tan 2014) asserts that social support consists of two dimensions informational and emotional support. Thus, social commerce constructs (recommendations and referrals, ratings and reviews and forums and communities) will help users to obtain social support within SNSs or online communities (Chen and Shen 2015; Liang et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2015). In other words, we decided to adopt this theory due to its significant role to create motivations between users in SNSs. When members of a particular online community got help from others in terms of exchanging their experience, knowledge and emotional support with other members, then other members in return will be motivated to return assistance to other members. Therefore, we believe that using social commerce constructs will enhance users’ social support (Liang et al. 2011).

3.2 Trust Theory

We adopted trust transfer theory (Stewart 2003), in particular, community trust (Chen et al. 2009; Zucker 1986) in building our proposed model. Cheng et al. (2019) define community trust as a way to reflect trust among members in social commerce platforms. Furthermore, community member trust (e.g. Cheng et al. 2019; Uslaner 2002) refers to building trust in a social context via motivating users’ interaction in specific social network platforms. Lindström (2014) employed this type of trust to outline trust between particular social network community members. Furthermore, community member trust is based on a shared relationship among particular community members. Hence, trust in SNSs community members is often based on trusting others and to feel trusted in return (Zucker 1986). As a result of the interaction which takes place via social commerce members and their evaluation of different attributes of a particular SNSs community, we believe that the linkage between social commerce constructs (recommendations and referrals, ratings and reviews and forums and communities) and community trust is of high significance. In other words, we believe that the interaction between users within social media will lead community member to trust each other in the same SNS. Thus, community members trust will be transferred from one user to the other as community members often trust each other more than they trust firms using social commerce on SNSs.

3.3 Social Presence Theory

Social presence theory is centred on human interpersonal relationships and it reflects the ability of a particular communication medium to convey social cues (Short et al. 1976). Therefore, social presence often reflects psychological intimacy and closeness. According to Rice and Case (1983), social presence reflects human feelings, warmth, sociability and sensitivity of a medium. Furthermore, we focused our efforts to test social presence theory within social commerce context due to the ability of this theory to enhance social interaction and communication between users of a particular SNS (Cui et al. 2013; Tu 2002; Xiao et al. 2019a). We have adopted social presence theory in this study to reflect users interacting and communicating with other users in SNSs and hence to have the ability to immerse themselves into SNSs virtual community. The linkage between social commerce and social presence theory comes as a result of the ability of social commerce constructs (recommendations and referrals, ratings and reviews and forums and communities) to facilitate the feelings of users over SNSs of their presence as a result of the interpersonal interaction among users (Huang and Benyoucef 2013; Liang and Turban 2011). Accordingly, users of SNSs will have an experience of being personally communicated via social commerce with a particular online community and hence users will be influenced by the presence of other users or their actions (Obeidat et al. 2020). Thus, users experience social presence that reflects their feelings, warmth, sociability and sensitivity of a particular online community within social commerce platform.

3.4 The Flow Theory

The flow theory centred around consumers’ level of involvement within a particular stimulus, and hence it reflects consumers’ feelings when they are fully absorbed with the experience of being on SNS (Csikszentmihalyi 1977; Gao and Bai 2014). We decided to adopt the flow theory due to its ability to generate a sense of immersion while consumers interacted with others within SNSs (Hsu et al. 2011; Gao and Bai 2014; Hoffman and Novak 1996; Mollen and Wilson 2010; Teng et al. 2012). Thus, users who are experiencing flow in a particular online community within social commerce platform will be highly involved in online community interaction, they will have an enjoyable experience while engaging with other users in a particular online community within SNS and they will have a sense of being fully absorbed. Therefore, we rely on the flow theory (Ding et al. 2010) and its implications within social commerce.

3.5 The Service-Dominant (S-D) Logic Theory

The notion of customer engagement has been rooted in the service-dominant (S-D) logic theory. The S-D logic theory is built on marketing relationships, which are characterised by customers’ interactive, and co-creative experiences with other stakeholders such as other customers, firms, and service personnel (Vargo and Lusch 2008). Lusch and Vargo (2010) assert that the notion of engaging is reflected by customer co-creative and interactive experiences. Within marketing context, the prior studies have highlighted engagement with social media to formulate customer engagement, which was defined as ‘a psychological state that occurs by virtue of interactive, co-creative customer experiences with a focal agent/object (e.g., a brand) in focal service relationships (Brodie et al. 2013, p.260). Furthermore, Brodie et al. (2013) assert that social media engagement is derived from customer engagement and hence it is a key dimension of customer engagement (Dessart 2017; Dessart et al. 2016). Accordingly, we adopted the S-D logic theory to investigate a particular part of customer engagement, namely, community engagement because: (i) community engagement reflects consumers’ dispositions regarding communities via different levels of affective, cognitive and behavioural displays, and (ii) Community engagement as a part of social media engagement reflects consumer interaction with other consumers in a particular online community (Brodie et al. 2013; Dessart 2017). Thus, we believe that high level of engagement with a particular online community will influence users’ affective, cognitive and behavioural aspects. We decided to adopt the S-D logic theory due to its ability to explain the main reasons of engagement in SNSs via customers’ interaction and value co-creation.

3.6 Hypotheses Development

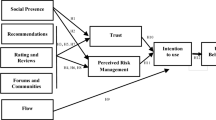

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed conceptual model. Further details are provided regarding the relationships between constructs. Majority of the relationships in the proposed conceptual model has been hypothesised considering support from previous literature within social commerce constructs. However, hypotheses such as H1c, H2, H3, H4a, H4b, H5 have not been tested within the context of social commerce constructs. Therefore, we believe that our research extends the current literature by testing relationships, which have not been investigated within the context of social commerce constructs in the emerging markets.

3.6.1 Social Commerce Constructs and Social Support

Previous studies posit the positive relationship between social commerce constructs and social support. For instance, within the context of online shoppers, Liang et al. (2011) posit that social commerce has a positive impact on social support. Li (2017) posits the positive significant relationship between social commerce constructs and social support (informational and emotional support). Hajli (2014) argues the positive linkage between social support dimensions, emotional support and informational support, and social commerce constructs (measured via recommendations and referrals and ratings and reviews). Hajli and Sims (2015) find a significant relationship between the constructs of social commerce and social support. Shanmugam et al. (2016) assert that forums, communities, recommendations and referrals, as well as ratings and reviews, in social platforms, allow consumers to interact with their peers within online communities or via social websites to exchange information and experience. The authors posit that social commerce constructs are essential tools to enhance social support. Furthermore, the authors find a positive significant relationship between social commerce constructs and social support (informational and emotional).

Thus, according to Crocker and Canevello (2008), social commerce constructs convey social support. Ridings and Gefen (2004) linked customers’ motivation to participating in social commerce with social support value (informational and emotional), which they can acquire. Social commerce constructs enhance customers’ social support through offering customers opportunities to rate products or services, to communicate with their peers, to review customers’ opinions, to make recommendations regarding products or services, and to share their experiences (Hajli 2013; Kapoor et al. 2018). As a result, social commerce provides shoppers, within online communities, with an informational and emotional support to help them solve their problems (Amblee and Bui 2011). Zhang et al. (2014) asserted that social commerce constructs help customers to interact with other customers and thus provide them with the opportunity to practice in social support. Hence, customers believe that reviews and ratings from other customers within social commerce sites are accurate and unbiased (Amblee and Bui 2011; Li 2017). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H1a: Social commerce constructs have a positive influence on social support

3.6.2 Social Commerce Constructs and Community Member Trust

Sharma et al. (2019) posit the positive association between ratings, forums and communities, interpersonal recommendations and trust in the social commerce environment. Hajli (2015) argues the positive association between social commerce constructs and trust within online community. Ha (2004) posits the positive association between social commerce constructs and trust among members. Sashi (2012) argues that social commerce constructs has an impact on customers’ trust. Kim and Park (2013) proposed that social commerce constructs impact online community trust. Customers’ ratings and reviews often facilitate trust between customers in the same community in SNSs (Utz et al. 2012). Within a virtual community, community members’ ability to help other members by providing correct and timely information via forums and communities enhances other users’ trust (Fogués et al. 2014; Lu et al. 2010). Banerjee et al. (2017) assert a significant impact of reviewer characteristics (involvement, experience, reputation) on community members’ trustworthiness. Within the context of online communities, Alalwan et al. (2019) assert the positive relationship between social commerce constructs and social trust. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

H1b: Social commerce constructs positively influence community member trust.

3.6.3 Social Commerce Constructs and Social Presence

Social commerce constructs within social media platforms allow users to interact with others, to exchange their ideas, information and experience and thus social commerce constructs facilitate, psychologically, the presence of other customers. Furthermore, social commerce constructs within SNSs allow consumers to be socially connected with their peers (Kang and Johnson 2013). Therefore, consumers within a particular community in SNSs considered social interaction with others as a credible source of information. Hence, the ability of social commerce constructs within SNSs online communities to facilitate ratings and reviews by other consumers (Park and Cameron 2014) often boost social interaction among customers and thus influence their perceptions of social presence. Furthermore, consumers’ recommendations as a significant reflection on customer experience play an important role in supporting other customers. Such personal experiences aid social interactions and therefore escalate social presence. Kumar and Benbasat (2006) assert that reviews and recommendations enhance online users’ perception of social presence. Li (2017) asserts the significant correlation between social commerce constructs and social presence. Thus, this study proposes that:

-

H1c: Social commerce constructs positively influence social presence.

3.6.4 Social Support and Community Member Trust

Previous research reports the significant association between social support and community member trust. For instance, Liang et al. (2011) suggest the significant relationship between social support and relationship quality (e.g. consumer-to-consumer trust). Weber and Johnson (2004) postulate the significant relationship between emotional support and trust. Xiao et al. (2019b) stress the significant relationship between intermediary trust and trust in user community. Söllner et al. (2016) assert the significant relationship between information quality, service quality, system quality and community trust. Zhou (2017) posits the significant relationship between social support dimensions (informational support and emotional support) and trust. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H2: Social support positively influences community member trust.

3.6.5 Social Presence and Community Member Trust

Social interaction between community members within SNSs reflects a type of social activity (Lu et al. 2016). Hence, social interaction provides an enriched platform for community members to learn from other members, to seek information and to share their experiences with others (Mardsen 2010). Therefore, community members of a particular social media platform can be effectively persuaded by other members who are similar to them, even if the community members are considered strangers (Cialdini 2001). During the purchase decision stage, Godes et al. (2005) posit that social interaction highly influences consumers’ attitudes, beliefs, and their behaviour. For instance, Cialdini (2001) states that consumers relied on their peers’ opinions when shopping online. Chen et al. (2011) postulate that consumers’ observations of other members’ purchase actions will shape their attitudes and behaviours. Sharma et al. (2019) posited a significant relationship between social presence and trust. Within the context of a social commerce platform, Lu et al. (2016) reported the significant relationship between social presence (perception of others) and trust. Lu et al. (2016) assert that consumers’ ability to interact with other members in the same SNS community allows them to get more information from community members and thus this kind of interaction enhances community members’ trust. Furthermore, the authors explain that interaction between different community members conveys a type of social presence. Thus, we propose that:

-

H3: Social presence positively influences community member trust.

3.6.6 Community Member Trust and Flow

Wu and Chang (2005) assert the significant association between community trust and flow. Community members often provide other members with relevant and useful information regarding different aspects and as a result, this interaction would help consumers to reduce costs, create trust between them, and make community members’ experience fruitful (Kim and Li 2009). Thus, community members’ interaction enhances members’ trust and hence facilitates their flow experience (Liu et al. 2016; MacKenzie and Lutz 1989; Zhou 2013; Zhu et al. 2019). In other words, community members’ interaction occurs due to the members’ involvement in online community and thus produces a flow experience (Liu et al. 2016; Gao and Bai 2014). Within online community, Liu et al. (2016) found a significant relationship between members’ trust and flow experience. Liu et al. (2016) posit that trust in community members (a trusted member is the one to who other members look at as a person with expertise, familiarity and similarity) enhances flow experience. Zhou (2017) posits the significant association between trust and flow. Thus, it is proposed that:

-

H4a: Community member’s trust positively influences flow.

3.6.7 Community Member Trust and Community Engagement

According to Kahn (1990), meaningfulness and safety are the main motivators for any community member to be engaged in any role. Within the context of online communities (McKnight et al. 2002a, b), community members’ trust with other members reflects community members’ belief in other users’ benevolence, ability, and integrity. Therefore, such belief creates a confidential expectation in community members to behave ethically (Gefen et al. 2003). Therefore, trust in community members leads to the belief in other community members’ efforts and values. Extant literature (e.g. Chan et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2018) argues that community member trust produces mutual benefits between community members and hence this type of trust is associated with the notion of engagement. Within social media brand communities, Liu et al. (2018) reported a significant relationship between community member trust and consumer engagement. Molinillo et al. (2019) assert the positive association between community trust and engagement. Vohra and Bhardwaj (2019) find a positive relationship between community trust and engagement with the community. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

H4b: Community member’s trust positively influences community engagement.

3.6.8 Flow Experience and Community Engagement

Previous research on the association between flow experience and engagement has been evidenced. For instance, Csikszentmihalyi (1977) asserts that flow experience produces deep engagement. Flow experience is considered a significant element within a social media usage context. Flow experience can facilitate users’ feelings of time and place when interacting with other users over social media (Wu and Wang 2011). This could be justified due to the ability of social media to enhance consumers’ feelings of flow, immersion and absorption. Within SNSs, Banhawi et al. (2012) reported the significant relationship between flow, which consumers have while navigating Facebook and their level of engagement. The authors assert that using Facebook leads to a feeling of focused attention and absorption that increases users’ engagement with Facebook. Hall-Phillips et al. (2016) reported that escapism and learning are significantly associated with engagement. Zhang et al. (2017) reported the impact of flow on online brand communities’ engagement. Triantafillidou and Siomkos (2018) revealed the positive influence of flow on behavioural engagement within a Facebook context. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

-

H5: Flow experience positively influences community engagement.

4 Methodology

To test the proposed hypotheses for this research, we collected the data from an official brand page on Facebook using a web-based survey, for active members in a Facebook online community during January 2019. We decided to conduct the current study using Facebook pages for the following reasons. Facebook is considered as the biggest social networking site in the world with more than 2.41 billion users and with a cumulative number of 2.7 billion users per month accessing the company’s main products such as Facebook, Messenger, WhatsApp and Instagram (Statista 2019). Additionally, Facebook pages are considered to be rich sources of information and they provide members with significant social benefits (De Vries et al. 2012). Previous research (Dessart 2017; Solem and Pedersen 2016) employed Facebook to measure the notions of consumer engagement and social media engagement. Solem and Pedersen (2016) considered Facebook as an active medium that enhances engagement.

Furthermore, Facebook helps a variety of brands to develop and to be easily shared among users via word-of-mouth. We decided to select an online community within Facebook which is centred on hybrid cars. This online community is located in Jordan, Middle East, and has almost 75 K members. The chosen page allows members to comment, to share their experiences, and it updates all the information frequently. Therefore, the chosen page aims to (i) facilitate exchanging experiences among the owners of the hybrid cars in terms of maintenance. (ii) Recommending the most trusted shops, which the owners can buy their spare parts from. (iii) Spreading word-of-mouth about engineers who are professional in dealing with hybrid cars. (iv) Advising the members of the best prices and quality of hybrid cars accessories, offers, and any other related aspects which might face the owners of such modern cars. Accordingly, two types of members join, follow and like this online community; individual users and firms. Online community members of this Facebook page follow the page’s posts and other members’ comments, views, and recommendations (Dessart 2017; Sharma et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2011). They can participate in the online community’s social activities, share their opinions and feelings and they exchange information with others. Furthermore, community members often interact with each other by replying and giving suggestions, which can help other members. On the other hand, firms also sponsor the community to share deals and offers to promote their brands (Chow and Shi 2015). For the purpose of our research, we focused on individual users and not firms.

We decided to conduct the current research on this particular online community due to the following reasons: (i) The chosen community members are increasingly dramatically due to new idea of the hybrid cars in the Middle East area and in particular in Jordan, (ii) The majority of hybrid cars owners are not familiar with many parts of such a new car in Jordan, hence hybrid car owners are indeed need all the help from consumers like them, (iii) Hybrid cars need more technology to track the origin of the car, particularly if it is used one. Therefore, the more educated members will help other members immediately once they are facing a problem and they seek aid.

4.1 Data Collection and Sample

We designed a questionnaire to measure the constructs of the current study (Weerakkody et al. 2007); social commerce constructs, social support, social presence, community member trust, flow and community engagement. Furthermore, we only included members who are active and have participated in the online community, at least over the last month of conducting the study. Therefore, we employed a non-probability (judgmental) sample form a particular online community to collect the data. Furthermore, we have employed a set of procedures to avoid sampling bias and to assure the current research validity and generalisability. For instance, (i) we collected our data from a large sample size (400 participants) to reflect generalisability of our results. Hence, our analysis is based on AMOS, and thus, we allowed 10–15 observations per indicator and not to exceed 500 as recommended by previous research (Al-Dmour et al. 2019; Hair et al. 2010), (ii) Our sample was distributed among our respondents’ characteristics in terms of gender, age, education level and time spent on the online community, (iii) We have conducted a nonresponse bias test (Armstrong and Overton 1977) for our current study and the results show no significant differences among participants (p > 0.05) for the study constructs of social commerce constructs, social support, social presence, community member trust, flow and community engagement and their sub-constructs, (iv) We employed Harman’s single factor test to ensure that there was no common method bias as we utilised a questionnaire filled in by the participants.

To ensure consistency in the current study and since the current study is conducted in Arabic, we translated our questionnaire first from English into Arabic and then we conducted the translation back into English (Brislin 1986). Furthermore, in order to examine the reliability and validity of the constructs’ items, we conducted a pilot study, prior to data collection, involving 50 MBA students. We obtained a total of 600 completed questionnaires, for the final study, of which 400 were valid. The sample constituted of 75% male and 25% female. Most (92%) of our sample respondents were less than 40 years of age; 85% have an undergraduate degree and 75% of them spent 1–2 h per day on the online community.

4.2 Measurement of Constructs

To measure social commerce constructs (second-order), we adopted the scale of Pagani and Mirab (2011, 2012) and Han and Windsor (2011), which consists of three first-order dimensions: ratings and reviews (three items), recommendations and referrals (4 items), and forums and communities (four items). To measure social support (second-order), we adopted the scale of Liang et al. (2011), which consists of two first-order dimensions: emotional support (four items) and informational support (three items). Social presence construct was measured by adopting the scale of previous research (Labrecque 2014; Gefen and Straub 2003; Rubin et al. 1985), which consists of four items. To measure community member trust, we relied on previous research (Cummings and Bromiley 1996; Luo 2005; Chen et al. 2009) consisting of three items. We relied on Zhang et al.’s (2014) scale to measure flow experience which consists of four items. To measure community engagement, we adopted Dessart et al. (2017) scale (second-order), which consists of three first-order dimensions i.e. affective engagement (six items), cognitive engagement (six items) and behavioural engagement (10 items) (see Table 2).

5 Results

To test our conceptual model, we used structural equation modelling using AMOS 24.0. Furthermore, we followed up with two more steps in our analysis. First, we conducted confirmatory factor (CFA) analysis for the constructs such as social commerce constructs (second-order), social support (second-order), social presence, community member trust, flow and community engagement (second-order). Second, we analysed the structural model to test our hypotheses.

5.1 Measurement Model

In the first stage of the CFA, we tested measurement model for all the reflective constructs: ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities, emotional support, informational support, social presence, community member trust, flow experience, affective engagement, cognitive engagement, and behavioural engagement. Our results show acceptable model fit indices (Hair et al. 2010; Hu and Bentler 1999) with χ2 = 1923.522, df = 756, and χ2/df = 2.544; CFI =0.922, GFI =0.905, TLI =0.916, IFI =0.923, and RMSEA = 0.062. We further tested our data for convergent validity, internal consistency and discriminant validity (Hair et al. 2010; Fornell and Larcker 1981). We find that all of the constructs under this study have composite reliability more than 0.7 achieving internal consistency (see Table 3). Furthermore, before calculating composite reliability, we deleted all the items that loaded under 0.7 on each of the reflective constructs. Therefore, all of the study items, under investigation, have significant coefficient values with their constructs. Thus, internal consistency has been achieved. Furthermore, we examined convergent validity by examining average variance extracted (AVE). Our results indicate that AVE values were above 0.50 – the recommended cut-off point (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Table 3 shows discriminant validity through the Pearson correlation between the constructs against square roots of AVE (presented along the diagonal) indicating an acceptable discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

For the second-order (formative) constructs, we also tested multicollinearity using psychological empowerment (Becker et al. 2012) to test for a higher-order construct of a reflective-formative type. We used variance inflation factor (VIF) for testing multicollinearity and our results indicate that values of the VIF ranges were less than 5. Furthermore, we find that all the items have positive and statistically significant values. Therefore, we find that we have nocollinearity problems (Hair etal. 2010) (see Table 4).

5.2 Common Method Bias

To avoid any issue related to common method bias, we applied Harman’s single factor test by putting items for all constructs together loaded into exploratory factor analysis and examined using an unrotated factor solution. We found that the first factor counted for 30.2% of the variance, which is less than 50% recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Therefore, this indicates that dataset does not have any concerns regarding common method bias.

5.3 Structural Model

We present the results of the structural equation modelling using AMOS 24 in Fig. 2 and Table 5 (Sharma 2019; Sharma et al. 2018). Our results show that social commerce constructs is multidimensional consisting of three first-order dimensions. We find that the paths of the three dimensions of social commerce constructs are significant: ratings and reviews (β = 0.80, p < 0.001), recommendations and referrals (β = 0.74, p < 0.001), and forums and communities (β = 0.78, p < 0.001). We find that the social support construct is also a multidimensional one consisting of two first-order dimensions: emotional support (β = 0.82, p < 0.001) and informational support (β = 0.81, p < 0.001). Furthermore, we find that community engagement is also a multidimensional construct consisting of three first-order dimensions: affective engagement (β = 0.82, p < 0.001), cognitive engagement (β = 0.85, p < 0.001), and behavioural engagement (β = 0.90, p < 0.001).

In support for H1a, we find that the notion of social commerce constructs (second-order) significantly influences social support (second-order, β = 0.75, p < 0.001). Furthermore, we find that social commerce constructs (second-order) positively influence community member trust (β = 0.52, p < 0.001). Thus, H1b is supported. In support for H1c, we find that the notion of social commerce constructs (second-order) positively influences social presence (β = 0.84, p < 0.001). Our results also supported H2 with the positive relationship between social support and community member trust (β = 0.20, p < 0.01). At the same context, we find that H3 arrives according to our expectations. We find that social presence is significantly related to community members’ trust (β = 0.21, p < 0.01). Our result for H4a shows that the relationship between community members’ trust and flow is supported (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Accordingly, we find that H4b for the relationship between community members’ trust and community engagement is supported (β = 0.75, p < 0.001). Finally, we find that H5 with the relationship between flow and community engagement is supported (β = 0.19, p < 0.01) with R2 value of 0.47. We find that indices for the structural model (i.e. χ2 = 2047.051, df = 763, χ2/df = 2.718; CFI = 0.913, GFI = 0.906, TLI = 0.911, IFI = 0.913, RMSEA = 0.066) are within the recommended limits (Hair et al. 2010).

6 Discussion

In support of the previous studies (e.g., Alalwan et al. 2019; Hajli 2015; Sheikh et al. 2019), our results confirmed the fact that the notion of social commerce constructs is a second-order one. Therefore, social commerce constructs should reflect ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities. Our results reveal that recommendations and referrals have the strongest influence on social commerce constructs. This result supports Sheikh et al.’s (2019) findings. This depicted that our sample in SNSs believe that recommendations and referrals are significant elements to enhance social commerce. This result reflects consumers’ belief in other consumers’ recommendations in order to conduct social commerce over social media platforms. In line with extant research (e.g., Alalwan et al. 2019; Algharabat 2017; Hajli 2015; Sheikh et al. 2019), we find that ratings and reviews count for the second strongest dimension of social commerce constructs.

In other words, customers’ ability to rate and review different content over social media platforms often encourages other customers to conduct social commerce over different social media platforms. In line with Sheikh et al. (2019) and Alalwan et al. (2019), we find that forums and communities are the third strongest dimension of social commerce constructs. Further, we find that social support is a multidimensional construct that encompasses two main dimensions namely emotional support and informational support. This result is also supported by existing literature (Chen and Shen 2015; Liang et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2015; Sheikh et al. 2019). Therefore, consumers within SNSs are information seekers, they are considered as valid sources for providing information to other users, and they will support them emotionally. Our results confirm that community engagement is a second-order construct consisting of three dimensions i.e. affective, cognitive and behavioural. We find that behavioural engagement was the strongest dimension followed by the cognitive dimension and then the affective dimension. Hence, customers are interested more in the behavioural dimension because this dimension reflects their ability to help other members, to seek information, to have positive word-of-mouth about the community and to be involved with other community members. This result supports previous research in this context (Dessart 2017).

We find that social commerce constructs significantly impact social support, community members’ trust and social presence (H1a, b, c). Accordingly, we find that the path coefficient value of the relationship between social commerce constructs and social presence (H1a) is 0.75, indicating that customers who are using SNSs for social commerce are interested in getting more informational support and emotional support from other members in the same community. Therefore, a social commerce construct enhances community members’ perception of the significant role of social support dimensions in which users of a particular SNS seek the support of others in terms of either information or emotion. This result is in line with Li (2017). The relationship between social commerce constructs and community members trust (H1b) comes as we expected, with a coefficient value of 0.52 indicating the important role, which social commerce constructs play in enhancing community members’ trust. Our result reveals that consumers’ ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities over SNSs encourage other community members to trust the content created by other members. Thus, as different community members interact with each other over a particular SNS it will create a kind of trust and hence common feelings will be shared by different members. This result has been supported in the extant literature (Alalwan et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2019; Sheikh et al. 2019). We find that the relationship between social commerce constructs and social presence (H1c) is supported, with a coefficient value of 0.84, indicating that social commerce constructs help community members to have a feeling of social presence. In other words, while community members over SNSs are interacting with each other via ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities, this will help community members to establish a sense of humanity just as if they are interacting with members they know and trust.

The relationship between social support and community members’ trust (H2) is significantly positive with a coefficient value of 0.20, indicating that consumers’ knowledge and emotional support, which they receive from a particular SNS community, influences their trust in the community. This result reflects the importance of SNS community members providing customers with the essential information they need and the emotional support to facilitate their decision-making. This result supports previous findings (Liang et al. 2011; Xiao et al. 2019b). In support of previous research (Chen et al. 2011; Lu et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2019), the relationship between social presence and community members’ trust (H3) was significantly positive with a coefficient value of 0.21, indicating that the sense of humanity during peer interaction in a particular SNS will increase a peer’s sense of trust with other community members. This result could be accredited to the fact that the people in the Middle East, as a collectivist culture, trust others as long as they provide them with the honest information and the required emotional support (Cialdini 2001).

The relationship between community members’ trust and flow (H4a) was approved, with a coefficient value of 0.30, indicating that community members’ trust, which customers often gain while interacting with other customers in the same SNS community, leads to flow experience. This result supported previous literature (Gao and Bai 2014; Liu et al. 2016; Zhou 2017). We find that the relationship between community members’ trust and community engagement (H4b) was supported with a coefficient value of 0.75, indicating that trust between different members in the same SNS community leads to more engagement with the community. Therefore, trust with other customers in the same SNS community will enhance users’ level of engagement regarding affective, cognitive and behavioural aspects. This finding is consistent with previous research (Chan et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2018). In other words, trust between community members will allow the members to emotionally engage with the community, to think positively about it and to act according to the community recommendations.

Hence, according to our results, when customers trust other customers within the same SNS community this will motivate them to have feelings of enjoyment, utilitarianism, to share their ideas with others, and to spread positive word of mouth. The relationship (H5) between flow and community engagement is as expected with a coefficient value of 0.19, indicating the positive relationship between flow and community engagement. The current result asserts that interacting with the online community will enhance flow experience in which community members will spend a lot of time following other community members’ reviews, feel fun, interested, excited, and absorbed. These types of feelings will motivate them to maximise their engagement with the community through having enjoyment value, utilitarian value, behavioural value to share their ideas with others, and to spread positive word of mouth. This result agrees with previous literature on the relationship between flow experience and community engagement (Hall-Phillips et al. 2016; Triantafillidou and Siomkos 2018; Zhang et al. 2017).

6.1 Contributions to Theory

We consider the following key points as our contributions to the current literature. First, to the best of our knowledge, none of the previous research has proposed the linkage between the proposed constructs, namely, social commerce constructs (second-order), social support (second-order), social presence, community member trust, flow experience and community engagement (second-order). Previous research has linked some of the above-mentioned constructs but not all of them. Therefore, we believe that we have contributed to the existing literature by developing a conceptual model, which has not been proposed before. Second, investigating a specific part of engagement is considered to be an addition to the literature.

For instance, previous research discussed customer brand engagement (Hollebeek et al. 2014), customer engagement (Vivek et al. 2012), and online community brand engagement (Wirtz et al. 2013). However, only the study by Dessart (2017) investigated community engagement, as part of social media engagement. Thus, we have contributed additional knowledge on community engagement and other relevant constructs in the developing world in general and an emerging market such as Jordan in particular. Third, the way we tested the relationships between constructs, in particular, the second-order constructs, is considered to be another contributions to the existing research. For instance, previous research linked social commerce constructs (second-order) with social support (second-order). However, none of the existing studies linked the relationships, using second-order of the three constructs namely social commerce constructs, social support, and community engagement.

6.2 Implications for Practice

The significant role of social commerce constructs’ dimensions (ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities) within Facebook platform at emerging markets makes the association among social commerce constructs, social support dimensions (information and emotion), social presence, community member trust, flow and community engagement dimensions (cognitive, affective, and behaviour) beneficial for social media marketing strategists. The current research has the following implications for social media strategists in general and for Facebook strategists in particular. First, online community strategists should enhance community members’ participation to rate, review, and recommend other members. In other words, community members should feel that they have the power to write and recommend what they feel and think about a particular issue, which is of interest to the community without the interference of the community managers. Our results assert that user interaction with other users via social commerce constructs often generate suggestions for others. Therefore, social media strategists should pay more attention to users’ opinion and thus to act accordingly to enhance users’ experiences over SNS platforms.

Thus, we suggest social media strategists to develop online communities, which users can join later in SNS to get social support, enhance their social presence and establish community trust. Second, community mangers should motivate the members to support other members via informational and emotional support. This could be achieved via the active participation of the members. Therefore, we believe that community managers play a vital role in enhancing and motivating community members’ interaction to help other members via answering their queries and having a more human touch. Doing this will increase community members’ trust in an online community. Thus, we suggest social media strategists to invest more in social commerce constructs (ratings and reviews, recommendations and referrals, and forums and communities) due to their significant role in promoting companies products and in understanding consumer behaviour. More specifically, based on our results, it is highly expected that utilising social commerce constructs will help social media strategists to develop and introduce new brands by enhancing user interaction. Third, to boost online community engagement, we recommend that online community strategists motivate community members to be more active in their participation and advising other members to recommend their online community.

6.3 Limitations and Future Research

Like any other research, this study also has some limitations. First, we collected the data from an online community in Facebook. Therefore, generalisation of our results should be implemented cautiously to other online communities outside Facebook. Second, our sample was from a developing country. Hence, the caution needs to be taken while generalising the findings to the developed countries’ context (Dwivedi and Williams 2008; Dwivedi et al. 2007, 2017; Rana et al. 2016). We advise future researchers to test our conceptual model in developing countries using different social media platforms. Furthermore, we recommend future researchers to replace community engagement with social media engagement and to test our model. Third, we recommend the future researchers to test different types of trust. Moreover, we also recommend future researchers to investigate social commerce IT artefacts and how such tools might impact consumer behaviour within social media platforms. Fourth, this research performed empirical validation of proposed research model using the one time cross-sectional data collected from Jordan (Alalwan et al. 2015, 2016a, b, 2017a, b, 2018; Algharabat et al. 2017; Baabdullah et al. 2019; Rana et al. 2015). Hence, the future research could collect longitudinal data to understand Facebook users’ community member trust and community engagement. Finally, the variance explained by the validated research model in community engagement is only 47%. Hence, the future research can include some additional constructs (e.g. social media language preferences) to see if the variance of the model could be improved (Kizgin et al. 2018; Sinha et al. 2019).

7 Conclusion

This study aims to build on the understanding of social commerce in the emerging markets and how it influences online community engagement. Using the Facebook online community, previous research proposed the linkage between some constructs such as social commerce constructs (second-order), social support (second-order), social presence, community member trust, flow experience and community engagement (second-order). However, existing have used only some of the above-mentioned constructs. We developed a conceptual model considering constructs from a number of different but relevant theories. The results revealed that social commerce constructs (second-order) positively influence social support (second-order), community member trust and social presence. Furthermore, we found that social support (second-order) and social presence positively affect community member’s trust. We also found that community member trust positively influences flow and community engagement whereas flow positively influences community engagement (second-order).

References

Agarwal, V., & Bharadwaj, K. K. (2011). Trust-enhanced recommendation of friends in web based social networks using genetic algorithms to learn user preferences. InInternational conference on computational science, engineering and information technology (pp. 476–485). Berlin: Springer.

Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Lal, B., & Williams, M. D. (2015). Consumer adoption of internet banking in Jordan: Examining the role of hedonic motivation, habit, self-efficacy and trust. Journal of Financial Services Management, 20(2), 145–157.

Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., & Williams, M. D. (2016a). Consumer adoption of mobile banking in Jordan: Examining the role of usefulness, ease of use, perceived risk and self-efficacy. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 29(1), 118–139.

Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., & Simintiras, A. C. (2016b). Jordanian consumers’ adoption of telebanking: Influence of perceived usefulness, trust and self-efficacy. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(5), 690–709.

Alalwan, A. A., Rana, N. P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Algharabat, R. (2017a). Social Media in Marketing: A review and analysis of the existing literature. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1177–1190.

Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Rana, N. P. (2017b). Factors influencing adoption of Mobile banking by Jordanian Bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. International Journal of Information Management, 37(3), 99–110.

Alalwan, A. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., & Algharabat, R. S. (2018). Examining factors influencing Jordanian customers’ intentions and adoption of internet banking: Extending UTAUT2 with risk. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 125–138.

Alalwan, A. A., Algharabat, R. S., Baabdullah, A. M., Rana, N. P., Raman, R., Dwivedi, R., & Aljafari, A. (2019). Examining the impact of social commerce dimensions on customers’ value co-creation: The mediating effect of social trust. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 18(6), 431–446.

Alalwan, A. A., Algharabat, R. S., Baabdullah, A., Baabdullah, A., Rana, N. P., Qasem, Z., Qasem, Z., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Examining the impact of mobile interactivity on customer engagement in the context of mobile shopping. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 33(3), 627–653.

Al-Dmour, H. H., Algharabat, R. S., Khawaja, R., & Al-Dmour, R. H. (2019). Investigating the impact of ECRM success factors on business performance: Jordanian commercial banks. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 31(1), 105–127.

Algharabat, R. (2017). Linking social media marketing activities with brand love: The mediating role of self-expressive brands. Kybernetes, 46(10), 1801–1819.

Algharabat, R. S. (2018). The role of telepresence and user engagement in co-creation value and purchase intention: Online retail context. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(1), 1–25.

Algharabat, R., Alalwan, A. A., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2017). Three dimensional product presentation quality antecedents and their consequences for online retailers: The moderating role of virtual product experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36, 203–2017.

Algharabat, R., Rana, N. P., Alalwan, A. A., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2018). The effect of telepresence, social presence and involvement on consumer brand engagement: An empirical study of non-profit organizations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 40, 139–149.

Algharabat, R., Rana, N.P., Alalwan, A.A., Baabdullah, A., & Gupta, A. (2020). Investigating the antecedents of customer brand engagement and consumer based brand equity in social media. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53.

Aljifri, H. A., Pons, A., & Collins, D. (2003). Global e-commerce: A framework for understanding and overcoming the trust barrier. Information Management & Computer Security, 11(3), 130–138.

Alrai Newspaper. (2019). 150 million dinars purchases of Jordanians through electronic commerce. Available at: https://alrai.com/article/10494815.

Amblee, N., & Bui, T. (2011). Harnessing the influence of social proof in online shopping: The effect of electronic word of mouth on sales of digital microproducts. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 91–114.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 396–402.

Asim, Y., Malik, A. K., Raza, B., & Shahid, A. R. (2019). A trust model for analysis of trust, influence and their relationship in social network communities. Telematics and Informatics, 36, 94–116.

Baabdullah, A., Rana, N. P., Alalwan, A., Islam, R., Patil, P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2019). Consumer adoption of self-Service Technologies in the Context of Jordanian banking industry: Examining moderating role of channel types. Information Systems Management, 36(4), 286–305.

Banerjee, S., Bhattacharyya, S., & Bose, I. (2017). Whose online reviews to trust? Understanding reviewer trustworthiness and its impact on business. Decision Support Systems, 96, 17–26.

Banhawi, F., Ali, N., & Judi, H. (2012). User engagement attributes and levels in Facebook. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 41(1), 11–19.

Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in pls-sem: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5/6), 359–394.

Biocca, F., Harms, C., & Gregg, J. (2001). The networked minds measure of social presence: Pilot test of the factor structure and concurrent validity. Paper presented at the presence, May 21–23, 2001, Philadelphia.

Biocca, F., Harms, C., & Burgoon, J. K. (2003). Toward a more robust theory and measure of social presence: Review and suggested criteria. Presence, 12(5), 456–480.

Brislin, R. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. Lonner & J. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105–114.

Calder, B. J., Malthouse, E. C., & Schaedel, U. (2009). An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23(4), 321–331.

Caspi, A., & Blau, I. (2008). Social presence in online discussion groups: Testing three conceptions and their relations to perceived learning. Social Psychology of Education, 11(3), 323–346.

Chan, T. K. H., Zheng, X., Cheung, C. M. K., Lee, M. K. O., & Lee, Z. W. Y. (2014). Antecedents and consequences of customer engagement in online brand communities. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 2(2), 81–97.

Chang, C.-M., & Hsu, M.-H. (2016). Understanding the determinants of users’ subjective well-being in social networking sites: An integration of social capital theory and social presence theory. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(9), 720–729.

Chen, J., & Shen, X.-L. (2015). Consumers' decisions in social commerce context: An empirical investigation. Decision Support Systems, 79, 55–64.

Chen, J., Zhang, C., & Xu, Y. (2009). The role of mutual Trust in Building Members' loyalty to a C2C platform provider. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 14(1), 147–171.

Chen, Y., Wang, Q., & Xie, J. (2011). Online social interactions: A natural experiment on word of mouth versus observational learning. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(2), 238–254.

Cheng, X., Gu, Y., & Shen, J. (2019). An integrated view of particularized trust in social commerce: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 1–12.

Chow, W. S., & Shi, S. (2015). Investigating customers’ satisfaction with brand pages in social networking sites. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 55(2), 48–58.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Harnessing the science of persuasion. Harvard Business Review, 79(9), 72–81.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1977). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Cui, G., Lockee, B., & Meng, C. (2013). Building modern online social presence: A review of social presence theory and its instructional design implications for future trends. Education and Information Technology, 18(4), 661–685.

Cummings, L. L., & Bromiley, P. (1996). The organizational trust inventory: Development and validation. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 302–330). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Curty, R. G., & Zhang, P. (2013). Website features that gave rise to social commerce: A historical analysis. Electron Commerce Research, 12(4), 260–279.

De Vries, L., Gensler, S., & Leeflang, P. S. H. (2012). Popularity of brand posts on brand Fan pages: An investigation of the effects of social media marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(2), 83–91.

Dessart, L. (2017). Social media engagement: A model of antecedents and relational outcomes. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(5–6), 375–399.

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Thomas, A. M. (2016). Capturing consumer engagement: Duality, dimensionality and measurement. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5–6), 399–426.

Ding, D. X., Hu, P. J.-H., Verma, R., & Wardell, D. G. (2010). The impact of service system design and flow experience on customer satisfaction in online financial services. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), 96–110.

Dwivedi, Y. K., & Williams, M. D. (2008). Demographic influence on UK citizens' e-government adoption. Electronic Government, an International Journal, 5(3), 261–274.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Khan, N., & Papazafeiropoulou, A. (2007). Consumer adoption and usage of broadband in Bangladesh. Electronic Government, an International Journal, 4(3), 299–313.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Janssen, M., Lal, B., Williams, M. D., & Clement, M. (2017). An empirical validation of a unified model of electronic government adoption (UMEGA). Government Information Quarterly, 34(2), 211–230.

Entrepreneur (2020). All set for growth: The E-Commerce Landscape in the Middle East. Available at: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/328467.

Fogués, R. L., Such, J. M., Espinosa, A., & Garcia-Fornes, A. (2014). BFF: A tool for eliciting tie strength and user communities in social networking services. Information Systems Frontiers, 16(2), 225–237.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marking Research, 18(1), 39–50.