Abstract

Climate change is a global crisis that requires countries to act on both domestic and international levels. This paper examines how climate policies in these two arenas are related and to what extent domestic and international climate ambitions are complementary or disparate. While scholarly work has begun to assess the variation in overall climate policy ambition, only a few studies to date have tried to explain whether internationally ambitious countries are ambitious at home and vice versa. According to the common view, countries that are more ambitious at home can also be expected to be more ambitious abroad. Many scholars, however, portray the relationship instead as disparate, whereby countries need to walk a tightrope between the demands of their domestic constituencies on the one hand and international pressures on the other, while preferring the former over the latter. This study uses quantitative methods and employs data from the OECD DAC dataset on climate finance to measure international climate ambitions. Overall, the present work makes two major contributions. First, it provides evidence that international climate financing ambition is complementary to domestic climate ambition. Second, the article identifies the conditional effect of domestic ambition—with regard to responsibility, vulnerability, carbon-intensive industry and economic capacity—on international climate ambition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) obligates developed countriesFootnote 1 to take ambitious domestic action to keep the rise in global temperature well below \(2^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) this century. Moreover, articles 4.3 and 4.4 of the 1992 UNFCCC agreement (UNFCCC 1992) and the Copenhagen Accord (UNFCCC 2009) require developed countries to contribute “new and additional” international assistance to developing countries—based on the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR & RC)—to address climate change. Studying the relationship between domestic and international climate policies is particularly timely, given that climate change is an urgent problem with a global impact, even though it is managed primarily within countries.

Since the 2000s, most developed countries have implemented policies at the local or national level to address imminent issues such as air pollution and energy efficiency. Climate change, however, is a global crisis that requires additional efforts at the international level (2015, 394). In response, developed countries promised at the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit to mobilize $100 billion in international climate finance per year by 2020 to help developing countries cope with the impact of climate change and the transition to low-carbon development.Footnote 2 The promise was reiterated in the Paris Agreement of 2015. Such assistance is commonly referred to as international climate finance (2014, 1238).

While funding for domestic climate policies is generally greater than for international policies (2016, 6), domestic and international climate ambition display significant variation. For instance, Burck et al. (2018, 18) find it noteworthy that “many countries, including Canada, Germany, Argentina and South Africa, are performing relatively well on the international stage, yet seem to be failing to deliver on sufficiently implementing policy measures at the national level”. Some contributions to the literature on environmental politics argue that countries are more likely to take international action when domestic policies are impeded (e.g., Michaelowa and Michaelowa (2007)); the question is whether international ambition to tackle climate change is complementary to or disparate from domestic action.

Research on the variation in domestic and international climate policies is on the rise (Madden 2014; Røttereng January 2018; Schmidt and Fleig 2018; Tobin 2017). Previous studies have investigated the general pattern of national climate policies (Schmidt and Fleig 2018); the effect of international support on domestic policies (Neuhoff 2009) compared the influence of domestic and international factors on ratification of environmental treaties (Bernauer et al. 2010; Dolšak 2009) and the influence of bureaucratic agencies (Peterson and Skovgaard 2019). Scholars have focused on the effect of democracy on climate policy (Bättig and Bernauer 2009), and on the impact of sub- or nonstate climate governance (Andonova and Tuta 2014; Andonova et al. 2017; Roger et al. 2017). Studies have generally focused on the impact of domestic politics on international climate negotiations or vice versa (Bulkeley 2010; Cass 2007; Dolšak 2009; Skjaerseth et al. 2013; Sprinz and Weiß 2001).

Very few papers (Castro 2020; Tosun and Guy Peters 2020), however, have combined an examination of domestic politics and institutions with a focus on international environmental politics (Van Deveer and Steinberg 2013). In this study, I am interested in determining whether domestic and international climate policies are complementary. Do more climate-ambitious countries tackle both levels of governance at the same time? Or do the two levels function disparately, with countries prioritizing one over the other?

The first part of the empirical analysis tests the correlation between domestic climate ambition and international climate finance in order to find out whether countries that are ambitious domestically also engage more ambitiously in international climate policy. This is achieved by way of a bivariate regression analysis, which is not aimed at identifying a causal relationship.

The second part of the study, however, tests whether domestic climate policy leads to higher international climate financing, and reviews the factors that likely moderate the relationship between domestic and international climate policies in developed countries. More specifically, I provide evidence of how the relationship is shaped by the responsibility for causing climate change, vulnerability to climate impacts, domestic industrial opposition and economic capability.

In the first section, I introduce the theoretical framework based on domestic and international climate ambition, and the moderating variables responsibility, vulnerability, industrial opposition and capability. This is followed by a second section, which describes the quantitative methods and data. The third section presents the empirical results. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion of the implications of the findings.

2 Theoretical framework

The question of whether climate change should be addressed domestically or globally is one of the central dilemmas of modern climate policy (Platjouw 2009, 244). While countries’ measures to tackle climate change are generally taken within their own borders, international climate policy has been argued to provide the most efficient solution for tackling climate change since greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced where reductions are marginally the cheapest (“low-hanging fruits”) (Castro 2010).

I define domestic ambition as complementary to international climate financing when countries tackle both levels ambitiously. By contrast, when countries are ambitious domestically and less so internationally, or vice versa, I discuss this as disparity. For instance, if a country is relatively ambitious internationally but takes less climate action domestically, I interpret this as disparity.

The current paper builds on emerging scholarship in the field of comparative climate policies, with an emphasis on international climate finance. I aim to contribute to this research field in some respects. First, this study aims to provide generalizable results regarding the potential complementarity of domestic and international climate ambition.

Second, I employ quantitative methods, which are still uncommon in this research area. Bernauer (2013, 434) notes that “[l]arge-N comparisons of many countries [...] are still rare”, as most of the peer-reviewed research exploring climate policy ambition has relied on qualitative methods and case studies (Compston and Bailey 2016; Genovese 2020; Ingold and Pflieger 2016; Korppoo 2020; Tobin 2017).

Third, whereas most recent studies on climate finance have focused on adaptation (Klöck et al. 2018; Robinson and Dornan 2016; Weiler et al. 2018), this study looks mainly at mitigation. This gives me an opportunity to compare international climate mitigation policy with its domestic counterpart. Most studies have addressed this issue by comparing domestic climate action with the outcomes of UNFCCC negotiations. I find international climate finance from public sources to be a more appropriate stand-in for international climate policy ambition, due to the “words-deeds” gap in policy-making (Bättig and Bernauer 2009). What countries agree upon at climate summits (“words”) does not necessarily translate into policy (“deeds”).

The policy community overwhelmingly expects international climate policy to be complementary to domestic climate policy. OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría (2017), for instance, hints that national climate policies and international climate financing create a powerful dynamic conducive to climate action. Eric Usher, head of the UNEP Finance Initiative, voiced a similar view to high-level representatives of the COP23 Finance for Climate Day in November 2017. Usher emphasized the two main gaps of the climate challenge: countries need to increase the domestic ambition of their NDCs (nationally determined contributions) and bridge the gap in global climate investment (international climate finance) (UNFCCC 2017).

Essentially, I ask the following overarching research question:

1. How are domestic and international climate policies related?

In addition to examining the relationship of complementarity and disparity, I aim in this paper to identify the factors that govern the variation in domestic and international climate policies. Consequently, I ask:

2. What factors affect the relationship between the level of ambition in domestic and international climate policy?

Thus, the second part of the analysis tests the premise that domestically ambitious countries are more likely to be active in international climate finance and that this relationship is moderated by additional factors. Many case studies argue that countries can maintain very different climate policy objectives domestically and internationally, as in the case of the Swiss climate commitment (Ingold and Pflieger 2016). Røttereng (January 2018, 70) claims that developed countries such as Canada and Japan conduct ambitious international climate policies, even as their own emission reduction targets are comparatively modest. This may be as Røttereng suggests, because countries do not want to be bound by domestic mitigation targets established by the international climate regime, even though they acknowledge mitigation as an international norm that needs to be upheld. Therefore, international climate spending may diverge from domestic efforts of climate change policy.

Most notably, (Putnam 1988, 434) points to an important cleavage between domestic and international policies. He describes domestic and foreign policy as a “two-level game”, wherein national administrations try to cope with pressures “[a]t the international level[...]” even while seeking to maximize ”[...] their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures”. This is supported by the emerging literature on voter behavior, which finds that the electorate prefers domestic spending on climate change policy, and views domestic and international policies as disparate (Buntaine and Prather 2018; Neuhoff 2009).

However, according to most of the literature on climate policy, domestic ambition is complementary to international ambition for three predominant reasons. First, foreign policies strengthen domestic climate policies because climate change is a global issue where national borders have little bearing on real outcomes. Funding spent at home should be essentially supplanted with funding spent abroad, because greenhouse gas emissions add to global atmospheric concentrations regardless of where they originate.

Second, a strong donor commitment to climate finance signals a high overall level of interest and engagement in domestic environmental protection. Michaelowa and Michaelowa (2011) suggest that donor governments’ “green beliefs” tend to extend to the international environmental arena. Third, countries may also exploit climate financing as an extension of domestic climate policy-making. Extensive support for international environmental financing may signal an interest in “internationalizing” domestic environmental policy (Falkner 2005, 587) and in leveling the playing field for domestic industry (Daniel and Vogel 2010). Developed countries with highly ambitious domestic climate policies may support emission reductions in developing countries due to the risk they run of losing industrial competitiveness (Castro 2010, 3).

The first step of this study is to investigate whether domestic and international climate policies are on average complementary or disparate. Due to the more common arguments in favor of complementarity, the first hypothesis may be stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1:

Countries with a higher domestic climate ambition display a higher ambition for international climate policy.

Hence, I assume that countries generally aim to tackle climate change but that their ambition at the international level tends to reflect their level of ambition at home.

I now proceed to the hypotheses associated with research question 2.

2.1 Responsibility

One of the most relevant factors in climate mitigation policy is the extent to which a country is responsible for causing anthropogenic climate change. This norm is internationally codified as the principle of CBDR & RC in Article 3.1 of the UNFCCC (1992), which states that the largest polluters bear the greatest responsibility for climate change and thus for providing financing to counter it. This reflects a “contribution to the problem” logic: countries that contribute more to cumulative GHG emissions (Page 2008, 557) are generally expected to shoulder a heavier burden in tackling climate change (Castro 2020). In terms of the relationship between domestic and international climate ambition, I hypothesize that countries that are more responsible tend to complement their domestic ambition with an international one. Thus, I expect countries that are already ambitious domestically to raise their international climate finance ambition to match their cumulative contribution to the problem of climate change. This yields the following hypothesis regarding responsibility and climate change ambition:

Hypothesis 2:

Countries with a higher domestic climate policy ambition and larger cumulative greenhouse gas emissions display a higher international climate ambition.

2.2 Vulnerability

Heggelund (2007) predicts that the importance of climate change in domestic policy-making will increase in line with vulnerability to climate change. What does this say about the relationship between domestic and international climate ambition? Sprinz and Vaahtoranta (1994) find that, in addition to reflecting the marginal cost of tackling climate change (abatement costs), international environmental efforts are conditional on a country’s ecological vulnerability, i.e., on the extent to which it is vulnerable to climate change (as seen in floods, sea level rise, wildfires, etc.), as well as on “its sensitivity, and its adaptive capacity” (Neil Adger 2006; Smit et al. 2000).

Vulnerability is not equally shared, and some developed countries are more vulnerable to climate change than others (Chen et al. 2015). The impact of climate change is international; it is conditional not on local but on global GHG emissions. More vulnerable countries would be compelled to prioritize international mitigation activities to protect themselves from rising sea levels and droughts. I expect vulnerability to lead domestically ambitious countries to increase their international climate ambition to safeguard against future climatic changes at home. This, in turn, means I expect domestically ambitious countries that are less vulnerable to climate change to reduce their international ambition due to a weak sense of urgency. Hence, I expect vulnerability to reinforce the complementarity of domestic and international climate ambition. This yields the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3:

Countries with a higher domestic climate policy ambition and a greater vulnerability to climate change display a higher international climate ambition.

2.3 Industrial opposition

The relationship between domestic politics and foreign policy has been a prominent motif in political science research since the publication of “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-level Games” by Putnam (1988), which recognized the tension between domestic lobby groups and pressure from other states. Kincaid and Timmons Roberts (2013), in their study of President Obama’s climate efforts, found support for the existence of a “two-level game”, in which the US administration needed to walk a tightrope between refraining from antagonizing industry with more stringent domestic climate regulations and pleasing environmental pressure groups that were calling for more climate aid. As a result, President Obama decided to elevate climate finance within the US budgetary agenda (Kincaid and Timmons Roberts 2013).

A high ambition for international climate policy can in fact reflect opposition from important interest groups to policies—at the domestic level, that is—for combating climate change (Christoff and Eckersley 2011; Madden 2014). This primarily concerns groups that are negatively affected by climate policies, such as fossil fuel and energy-intensive industries, whose profit margins are dependent on actively resisting ambitious domestic climate policies. Steves and Teytelboym (2013) and Rafaty (2018) confirm this expectation: they find that a strong carbon-intensive industry hinders the adoption of domestic climate policies. Michaelowa and Michaelowa (2007) note that policymakers may turn to international climate finance when a far-reaching domestic climate commitment is strongly opposed by industry lobby groups. Ingold and Pflieger (2016, 32–33) conclude that domestic interest groups will oppose restrictive domestic climate measures but remain apathetic toward international climate policies that do not affect them immediately. Daniel and Vogel (2010), however, argue that carbon-intensive industries will likely even support international efforts if restrictive measures are already in place at the domestic level. The internationalization of climate policy helps the industry “level the playing field”, since it forces foreign competitors to adhere to the same strict standards as those that apply domestically.

I expect domestic climate ambition to be associated with ambition abroad, but in a way that is moderated by strong industrial interest groups. Hence, countries with a higher domestic climate ambition and strong industrial groups will invest more abroad. Conversely, countries with a lower domestic ambition and strong industries will invest less abroad. This reflects the logic identified by Daniel and Vogel (2010) to the effect that industrial groups will seek to “level the playing field abroad”. This yields the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4:

Countries with a higher domestic climate ambition and a larger carbon-intensive industrial sector display a higher international climate ambition.

2.4 Capability

The third explanatory factor is a country’s economic capability, as stated in the principle: “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”. In general, much of the literature on environmental policy assumes that higher economic development and greater resources are conducive to environmental policy-making. Fordham (2011) indicates that the “capabilities-drive-intentions” model provides a persuasive explanation for the foreign policy ambition of states, since “[o]nce the state becomes able to extract sufficient resources from society, it will use them to pursue a more ambitious foreign policy” (Fordham 2011, 589). This also reflects the importance of the “ability to pay” principle, as countries with the greatest resources can reasonably be required to contribute more to tackling the problem (Page 2008, 561).

However, empirical studies on the effect of economic development on domestic and international policies have been inconclusive. Halimanjaya (2015) observes a negative relationship between GDP per capita and international climate financing, while Madden (2014) discovers that higher-income developed countries are less willing to adopt highly ambitious domestic climate policies. Both Hicks et al. (2008) and Klöck et al. (2018) find that wealthier countries contribute more to global environmental projects. Therefore, I expect climate finance to be a “luxury” that greener countries can afford due to surplus economic resources. Hence, while countries provide more climate finance once they are more ambitious at home, their international commitment increases even when they have abundant resources. This yields the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5:

Countries with a higher domestic climate ambition and higher GDP per capita display a higher international climate ambition.

3 Methods

Bernauer (2013, 436) concludes that political science research has primarily emphasized the use of qualitative methods and case studies for studying variation in climate change policies (Harrison and Sundstrom 2010). In this study, I aim to provide further generalizability by employing quantitative methods. More specifically, I make use of bivariate regression and of interaction effects to capture changes in climate finance ambition. I also use country fixed effects to avoid violating the assumption that observations are independent and identically distributed.

This study is focused on rich developed countries that are members of the OECD, which includes all “Annex II” group countries (except Turkey) and the Republic of Korea. These are the member countries of which according to the UNFCCC have a responsibility to reduce carbon emissions at home and to provide international climate finance abroad. The overall sample comprises 24 countries over the 2008–2017 period. The data comprise 232 observations due to missing values for some years (Table 1).

I employ international financing for climate change mitigation as a dependent variable, inasmuch as I find it a reasonable expectation that efforts in this direction will be implemented after domestic climate policies have been instituted. Countries in the dataset enacted domestic climate policies temporally earlier than their engagement with international climate financing. Moreover, domestic climate policies are known to be more likely due to their local impacts and are more likely to be a priority of countries than international efforts (as proposed by hypothesis 1).

I measure international climate ambition on the basis of OECD DAC country-level data on “Rio Marker” climate change, which provides information on the amount of bilateral and multilateral climate finance that OECD countries provided to developing countries during the 2008–2017 period (expressed in constant 2014 dollars). The data are self-reported by countries, which may cause inconsistencies, such as over-coding and a lack of granularity. See Weikmans and Timmons Roberts (2019) to obtain a larger picture of the potential problems. Nevertheless, the OECD data are currently the most comprehensive and comparable dataset available for public climate-related finance flows (Klöck et al. 2018). I aim to overcome at least some of the issues by introducing a control variable on overall ODA flows.

The data on countries’ commitment in this study consist of grant or loan agreements made between donors and recipients. This provides a more recent overview of donor decisions (Betzold and Weiler 2017; Peterson and Skovgaard 2019) and yields more years. The level of climate mitigation finance is presented as climate-related funding per GDP to developing countries per donor and year, as in other studies (Halimanjaya 2015; Klöck et al. 2018; Peterson and Skovgaard 2019). The study accounts for the funding of all projects that have principal and significant climate objectives.Footnote 3 As the dependent variable is skewed among the higher values of the distribution, I transform the variables using the natural logarithm.

To test my hypotheses, I employ the conceptually most rigorous measure for domestic climate mitigation ambition currently available: the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI)—which is published by Germanwatch, CAN International and the NewClimate Institute. More specifically, I employ the CCPI’s subindicator on national climate policy, which is based on a questionnaire distributed among climate change experts at national NGOs (Burck et al. 2018, 19). The measure ranges from 0 to 20, with higher values representing higher ambition. The questionnaire covers issues on domestic climate mitigation policies, such as energy efficiency, the promotion of renewable energies and efforts to reduce emissions from electricity production, manufacturing and transport. Moreover, the subindicator rates each country’s deforestation, forest degradation and national peatland protection efforts (Burck et al. 2018). In effect, the subindicator largely measures a country’s climate ambition based on experts’ evaluation of its domestic climate policies compared with its potential capability. As a softer test of causality, the variable is lagged by one year to check whether values from the preceding year have a bearing on the provision of mitigation finance in the following year.

This study includes a logged GDP per capita term. I follow the standard practice of development aid literature as set out by Alesina and Dollar (2000) and Weiler et al. (2018); thus, I use GDP per capita (GDP/capita in the model) as collected by the World Bank (2018a). To account for the emission intensity of each country’s economy, I include country \(\hbox {CO}_{2}\) emission intensity (\(\hbox {CO}_{2}\) emissions per GDP), which is log transformed to counter the skewness of the variable (CDIAC 2018), as GDP per capita can vary significantly even between high-income countries.

I measure responsibility for causing climate change by using the Global Carbon Project’s (GCP 2019) dataset on cumulative carbon emissions as a proxy for all GHGs. The variable is transformed using the natural logarithm due to the large differences between low and high emitters caused by the variation in the size of economies.

To account for vulnerability to climate change, I incorporate the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative’s (ND-GAIN) vulnerability indicator (NDGAIN 2018), defined as the “[p]ropensity or predisposition of human societies to be negatively impacted by climate hazards” (Chen et al. 2015, 3). The indicator measures vulnerability through six life-supporting sectors (food, water, health, ecosystem services, human habitat and infrastructure). Each sector is represented by subindicators that account “for exposure of the sector to climate-related or climate-exacerbated hazards, the sensitivity of that sector to the impacts of the hazard and the adaptive capacity of the sector to cope or adapt to these impacts” (ibid.). The indicator ranges from \(-0.086\) to 0.128 for the selected sample. Lower values of the indicator (Vulnerability in the model) represent lower vulnerability to climate change, and higher values signify higher vulnerability. As vulnerability tends to correlate significantly with economic resources, this study uses a version of the indicator adjusted for GDP.

This study employs an approximate proxy for industrial opposition, as no comparative data are available for the size or number of industry sector lobby groups across countries. Analogous to Steves and Teytelboym (2013), I employ the size of carbon-intensive industry (manufacturing, mining and utilities) relative to GDP from UNSD (2018) to measure industrial opposition. Capability is measured by way of GDP per capita data (PPP) in constant 2011 US dollars (World Bank 2018b).

The study does not attempt to “reinvent the wheel”: rather, it includes a number of control variables that have proven fruitful in previous studies on development aid and climate finance (Alesina and Dollar 2000; Berthélemy 2006; Klöck et al. 2018). Following (Halimanjaya 2015; Klöck et al. 2018), I control for each country’s institutional capacity for effective administration by using the sum of the six subindicators of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) (Kaufmann et al. 2010). I expect better governed countries to be more likely to provide more international climate finance. Next, I use the World Bank (2018b) data to control for yearly country population size. I anticipate that larger countries will take less action per capita due to the sheer volume of their aid efforts. Finally, I take into account the total flows of Official Development Assistance, on the expectation that international climate financing is at least partly determined by path dependence arising from overall aid-giving (as previous researchers have found (Klöck et al. 2018, 16)). All control variables are lagged by one year on the expectation that decisions on international climate finance allocation are made based on knowledge from the antecedent year.

First, I employ a bivariate regression model to investigate the association between domestic and international climate policy. I estimate the bivariate regression:

where the dependent variable \(\gamma _{\textit{it}}\) is the natural logarithm of climate mitigation finance per GDP by donor i in year t. \(\chi _{\textit{it-1}}\) corresponds to the main explanatory variable of interest, which is the domestic climate mitigation policy indicator lagged by one year. \(\epsilon\) represents the error term.

Second, I use three separate interaction models, which estimate each moderating variable—vulnerability, industry opposition and resources—independently in each model:

I make the argument that \(\chi\) (domestic climate ambition) has an effect on \(\gamma\) (international climate ambition). This relationship, however, is moderated by (vulnerability), (resources) and (industrial opposition), which are represented by \(\delta\). \(\eta\) stands for control variables, \(\kappa\) is a vector of controls for country i and \(\epsilon\) stands for the error term.

To capture the differences in context by industry, exposure to climate change and differences in income, I employ interaction terms, which follow the principles of correct model specification suggested by Brambor et al. (2006): I include all constitutive terms in the model specification and analyze the marginal effects of substantively meaningful interaction termsFootnote 4. Models (2-5) show different interaction terms based on the aforementioned hypotheses. To maintain comparability, all models include the same control variables and the same number of country-year observations (210). I also run robustness tests by including an alternative dependent variable (mitigation and adaptation combined) and independent variables (e.g., full CCPI index, economic growth) and other hypotheses (budget deficits and green technology patents (OECD 2021a, b)), as presented in Table 3.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive results

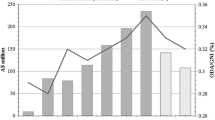

Figure 1 shows average levels of domestic climate policy ambition (CCPI national climate policy indicator) and average levels of international climate ambition (natural logarithm of public finance for climate change mitigation as a share of GDP) that countries displayed during 2008–2017. The relationship appears to be visually linear, but it includes distinct outliers, such as Japan and Portugal. At least three different country strategies can be identified. Many of the countries—among them Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Luxembourg, New Zealand and others—fit the hypothesized results and stay close to the regression line, appearing to complement their domestic ambition with the same level of international ambition. Another group consists of front-runner countries that promote ambitious climate policies at home, while also spending comparatively more on climate finance abroad; these include France, Germany and Norway. The other two strategies stray from this pattern by either being more committed to climate policies at home (Portugal, South Korea and the UK) or more engaged in international climate financing (Japan).

This is in line with several country case studies. Germanwatch (2019) country report on Portugal notes that country’s high ranking on domestic climate policy is primarily due to its “government’s commitment to the carbon neutrality target by 2050 [...] and to a coal phase-out recently anticipated to 2023, which is to be achieved by means of 100% renewable energy in the mid-century”. By contrast, international climate financing appears to be less integrated into Portugal’s overall development strategy (Camões 2015). Previous case studies also support the results for Japan. Climate Action Tracker (Climate Action Tracker 2013, 3) observes a general shift in focus in the case of that country from domestic to international emissions reductions. While Japan has reduced its domestic climate ambitions, it has also concurrently increased its efforts to provide international climate finance.

4.2 Regression results

Table 2 presents the results of all of the models. Model 1 aims to provide descriptive results for the main bivariate regression, while models (2)–(5) include all control variables and interaction terms for hypotheses 2–5. In general, models (2)–(5) fit the data well, as the adjusted \(R^{2}\) is over 80 percent in all interaction models. All interaction models include all of the control variables, and all country- and year-fixed effects. As per Keele et al. (2020), the main interaction models do not present the results for the control variables, since covariates do not carry a causal or substantive interpretation. The constitutive term on domestic ambition in models (2)–(5) captures the effect of domestic ambition on international climate commitment when the associated moderating variable is zero.

As I hypothesized and as shown by Fig. 1, the descriptive bivariate model (1) in Table 2 demonstrates that a higher level of domestic climate ambition is positively associated with a higher level of international climate ambition. This result provides support for hypothesis 1—that domestic climate policy is complementary to international climate finance, as developed countries that are more ambitious at home are also more likely to be ambitious internationally. To determine why that should be, I test 4 additional hypotheses on domestic climate policy and specific moderating factors (responsibility, vulnerability, industrial opposition and capability). The following results are specific to climate mitigation finance but fairly robust to full climate finance data (total for mitigation and adaptation) in Table 3.

4.2.1 Responsibility

I will focus first on model (2) in Table 2, which tests hypothesis 2. The interaction term of domestic climate ambition and responsibility is statistically significant with a positive coefficient. This result is in line with the “idealist” expectation of UNFCCC (1992), which requires that countries commit to international climate finance based on their “common but differentiated responsibilities”. Thus, I find support for hypothesis 2—the effect of domestic climate policy ambition on international climate finance increases with greater responsibility for causing climate change. This result is reinforced by the marginal effects in Fig. 2, that show that countries which are more ambitious domestically provide more climate mitigation finance at higher levels of responsibility. Countries that are less responsible, however, commit less international climate finance per domestic ambition.

4.2.2 Vulnerability

I will turn next to hypothesis 3 in model (3). Unlike Klöck et al. (2018), I discover a strong negative relationship between vulnerability, domestic climate ambition and ambition for international climate finance. The results show that countries that are more ambitious at home provide less international climate finance if they are more threatened by climate change. This suggests that vulnerability to climate change does not push domestically ambitious countries to take more action abroad. Accordingly, I reject hypothesis 3. Unexpectedly, it is the domestically least ambitious countries, which ceteris paribus are more likely to increase their climate finance ambition once their vulnerability intensifies. It appears that higher vulnerability leads to lower domestic action vis-a-vis international ambition.

4.2.3 Industry opposition

The importance of carbon-intensive industry (as share of GDP) is included in model (4) as an interaction term with domestic climate ambition. The negative effect of carbon-intensive industry in the model appears to be conditional on domestic climate ambition at the 90% confidence level. These results suggest that the effect of domestic ambition on international climate finance decreases as the carbon-intensive industrial sector increases (Fig. 2). This also means that domestically ambitious countries begin to provide more climate finance as their industrial sector decreases. The results provide some support for the thesis that the industry sector drives disparity in domestic and international climate ambition. The reason may be that countries with large carbon-intensive industries, such as South Korea and Norway, support one dimension over the other, either locally or internationally. Nevertheless, this result is at variance with the theoretical expectations of the regulatory politics framework, to the effect that restrictive domestic policies will lead to a greater use of climate financing in order to support industry’s efforts to “level the playing field” abroad. This leads me to reject hypothesis 4.

4.2.4 Capability

Model (5) shows that a greater abundance of economic resources decreases the effect of domestic climate ambition on international climate finance. The interaction term of domestic ambition and GDP per capita is statistically significant. Figure 2 shows that poorer countries (below the Annex II average) provide more funding when their domestic ambition is high. This effect decreases, however, among the wealthiest countries (Fig. 2). I conclude that the effect of domestic ambition on international climate finance decreases with income. This result suggests a basis for rejecting hypothesis 5, and it provides evidence that domestic “greenness” is more important for international ambition than additional wealth.

5 Conclusion

By examining international climate finance, I have provided generalizable results on the complementarity of international and domestic climate ambition. My study has included public funding for climate change mitigation and taken into account the responsibility of different countries for causing climate change, as stated in the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. My main contribution to the literature is the finding that countries with more ambitious climate policies at home are also more likely to be more committed abroad. This effect is conditional, however, on several factors.

The main contribution of the study is the disaggregation of domestic and international climate action. I find support for the first part of the “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” principle, but not for the second. Everything considered, my analysis shows that domestically committed countries provide more climate mitigation financing and that this effect increases with cumulative carbon emissions (responsibility). However, my results do not support the argument that climate financing is a “luxury” that richer countries can afford due to excess wealth (capability). In contrast, excess resources do not matter for countries that are domestically ambitious. The theoretical implication of this study is thus that countries’ international climate ambition is driven by a combination of responsibility and domestic ambition. An abundance of economic resources, by contrast, is associated with disparity.

I also find a moderating effect of industry opposition. Domestically “green” countries with a sizable carbon-intensive industrial sector provide less international climate financing. This result defies the expectation that carbon-intensive industries would be more supportive of renewable energy investments and the expansion of strict climate ambition abroad in countries that have stricter domestic policies in place. Instead, a large carbon-intensive industrial sector is more likely to encourage disparity, with domestically ambitious countries reducing their international ambition. This finding contradicts the theoretical expectation that exposure to climate change will increase the importance of international climate policy. Rather, my analysis shows that domestically ambitious countries may become even less interested in tackling climate change on a global level as their vulnerability to climate change increases.

This research has vital implications for climate change policy. I find that increased vulnerability, a strong carbon-intensive industry and a stronger economic capability are not enough to increase a country’s international commitment when it is already ambitious at home. Instead, I find that domestically “green” countries are more likely to be influenced by calls for increased international responsibility. Future research can complement the present study, in particular by adopting a comparative framework for qualitative analysis and by encompassing a wider range of domestic political factors, including the role of national and transnational actors.

Notes

In this case I refer to Annex II countries as developed countries.

Nevertheless, climate finance needs to be distinctly differentiated from climate aid. Developed countries argued for integrating development aid and climate finance. Developing countries, in contrast, contended that climate finance should be treated as a separate obligation from development assistance (2015, 151)—in accordance with the Copenhagen Accord, which calls for “new and additional” finance from new sources separate from ODA. Climate finance refers to more general type of funding for climate purposes, while the latter refers to funding strictly for development assistance.

Coal-related funding has been dropped from the dataset (consistently discounted in OECD reporting) in order to focus strictly on climate-related funding (OECD 2018).

The study also applies the diagnostic methods proposed by Hainmueller et al. (2019) for assessing the validity of the linear interaction effect assumption.

References

Adger, W. N. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006.

Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of Economic Growth, 5(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009874203400.

Andonova, L. B., & Tuta, I. A. (2014). Transnational networks and paths to EU environmental compliance: Evidence from new member states. Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(4), 775–793.

Andonova, L. B., Hale, T. N., & Roger, C. B. (2017). National policy and transnational governance of climate change: Substitutes or complements? International Studies Quarterly, 61(2), 253–268.

Bättig, M. B., & Bernauer, T. (2009). National institutions and global public goods: Are democracies more cooperative in climate change policy? International Organization, 63(2), 281–308.

Bernauer, T. (2013). Climate change politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 421–448. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-062011-154926.

Bernauer, T., Kalbhenn, A., Koubi, V., & Spilker, G. (2010). A comparison of international and domestic sources of global governance dynamics. British Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 509–538.

Berthélemy, J.-C. (2006). Bilateral donors’ interest vs recipients’ development motives in aid allocation: Do all donors behave the same? Review of Development Economics, 10(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00311.x.

Betzold, C., & Weiler, F. (2017). Allocation of aid for adaptation to climate change: Do vulnerable countries receive more support? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9343-8.

Brambor, T., Roberts, W., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpi014.

Bulkeley, H. (2010). Cities and the governing of climate change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35(1), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-072809-101747.

Buntaine, Mark T., & Prather, L. (2018). Preferences for domestic action over international transfers in global climate policy. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 5(1), 1–15.

Burck, J., Marten, F., Bals, C., Uhlich, T., Höhne, N., Gonzales, S., & Moisio, M. (2018). Background and methodology. Germanwatch: Climate Change Performance Index.

Camões, I. P. (2015). Portugals aid at a glance. 2015. Technical report, Instituto Camões.

Cass, L. R. (2007). Measuring the domestic salience of international environmental norms: Climate change norms in German, British, and American climate policy debates. In The Social Construction of Climate Change, p. 28. Routledge, 1st edition edition.

Castro, P. (2010). Climate change mitigation in advanced developing countries: Empirical analysis of the low-hanging fruit issue in the current CDM. CIS Working Paper 54.

Castro, P. (2020). National interests and coalition positions on climate change: A text-based analysis. International Political Science Review, page 0192512120953530, ISSN 0192-5121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120953530.

CDIAC. (2018). Fossil-Fuel CO2 Emissions. https://cdiac.ess-dive.lbl.gov/trends/emis/meth_reg.html.

Chen, C., Noble, I., Hellmann, J., Coffee, J., Murillo, M., & Chawla, N. (2015). University of Notre Dame global adaptation index. Notre: University of Notre Dame.

Christoff, P., & Eckersley, R. (2011). Comparing state responses. In J. S. Dryzek, R. B. Norgaard, & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society, Oxford handbooks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Climate Action Tracker. (2013). Japan: From frontrunner to laggard. Climate Analytics, New Climate Institute: Technical report.

Compston, H., & Bailey, I. (2016). Climate policy strength compared: China, the US, the EU, India, Russia, and Japan. Climate Policy, 16(2), 145–164.

Daniel, R., & Vogel, D. (2010). Trading places: The role of the United States and the European Union in international environmental politics. Comparative Political Studies, 43(4), 427–456.

Dolšak, N. (2009). Climate change policy implementation: A cross-sectional analysis. Review of Policy Research, 26(5), 551–570.

Falkner, R. (2005). American hegemony and the global environment. International Studies Review, 7(4), 585–599.

Fordham, B. O. (2011). Who wants to be a major power? Explaining the expansion of foreign policy ambition. Journal of Peace Research, 48(5), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343311411959.

GCP. (2019). Global Carbon Project (GCP). https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget/.

Genovese, F. (2020). Domestic sources of ’mild’positions on international cooperation: Italy and global climate policy. Italian Political Science, 15(1), 1–19.

Germanwatch. (2019). Country Results: Portugal. https://www.climate-change-performance-index.org/country/portugal.

Gupta, S., Harnisch, J., Barua, D. C., Chingambo, L., Frankel, P., Garrido Váquez, R. J., G ómez-Echeverri, L., Haites, E., Huang, Y., Kopp, R., Lef èvre, B., Machado-Filho, H., & Massetti, E. (2014). Cross-cutting investment and finance issues. In Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., Kriemann, B., Savolainen, J., Schl ömer, S., von Stechow, C., Zwickel, T., & Minx, J. C., (eds) Climate change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Inter- Governmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Gurría, A. (2017). Climate action: Time for implementation. Toronto: Munk School of Global Affairs.

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Yiqing, X. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis, 27(2), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.46.

Halimanjaya, A. (2015). Climate mitigation finance across developing countries: What are the major determinants? Climate Policy, 15(2), 223–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2014.912978.

Harrison, K., & Sundstrom, L. M. (2010). Global commons, Domestic decisions: The comparative politics of climate change. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heggelund, G. (2007). China’s climate change policy: Domestic and international developments. Asian Perspective, 31(2), 155–191.

Ingold, K., & Pflieger, G. (2016). Two levels, two strategies: Explaining the gap between swiss national and international responses toward climate change. European Policy Analysis, 2(1), 20–38.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Number 5430 in Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank, Development Research Group, Macroeconomics and Growth Team, Washington, DC

Keele, L., Stevenson, R. T., & Elwert, F. (2020). The causal interpretation of estimated associations in regression models. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.31.

Kincaid, G., & Roberts, J. (2013). No talk, some walk: Obama administration first-term rhetoric on climate change and US international climate budget commitments. Global Environmental Politics, 13(4), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00197.

Klöck, C., Molenaers, N., & Weiler, F. (2018). Responsibility, capacity, greenness or vulnerability? What explains the levels of climate aid provided by bilateral donors? Environmental Politics: Advance online publication.

Korppoo, A. (2020). Domestic frames on Russia’s role in international climate diplomacy. Climate Policy, 20(1), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1693333.

Madden, N. J. (2014). Green means stop: Veto players and their impact on climate-change policy outputs. Environmental Politics, 23(4), 570–589.

Michaelowa, A., & Michaelowa, K. (2007). Does climate policy promote development? Climatic Change, 84(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-007-9266-z.

Michaelowa, A., & Michaelowa, K. (2011). Climate business for poverty reduction? The role of the World Bank. The Review of International Organizations, 6(3–4), 259–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-011-9103-z.

NDGAIN. (2018). Rankings: Notre dame global adaptation initiative. https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/rankings/

Neuhoff, K. (2009). Understanding the roles and interactions of international cooperation on domestic climate policies. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

OECD. (2018). Climate finance from developed to developing countries: 2013–17 public flows. Technical report, OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2021a). Patent indicators. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PAT_IND.

OECD. (2021b). General government—General government deficit—OECD Data. http://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-deficit.htm.

Page, E. A. (2008). Distributing the burdens of climate change. Environmental Politics, 17(4), 556–575.

Peterson, L., & Skovgaard, J. (2019). Bureaucratic politics and the allocation of climate finance. World Development, 117, 72–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.12.011.

Pickering, J., Skovgaard, J., Kim, S., Roberts, J., Rossati, D., Stadelmann, M., & Reich, H. (2015). Acting on climate finance pledges: Inter-agency dynamics and relationships with aid in contributor states. World Development, 68, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.033.

Froukje Maria Platjouw. (2009). Reducing greenhouse gas emissions at home or abroad? The implications of Kyoto’s supplementarity requirement for the present and future climate change regime. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law, 18(3), 244–256.

Putnam, R. D. (1988). Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International organization, 42(3), 427–460.

Rafaty, R. (2018). Perceptions of corruption, political distrust, and the weakening of climate policy. Global Environmental Politics, 18(3), 106–129.

Robert, L., Hicks, B. C., Parks, J., Timmons, R., Michael, J. T. (2008). Greening aid?: Understanding the environmental impact of development assistance. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-958279-2

Robinson, S., & Dornan, M. (2016). International financing for climate change adaptation in small Island developing states. Regional Environmental Change, pp 1–13. ISSN 1436-3798, 1436-378X. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1085-1.

Roger, C., Hale, T., & Andonova, L. (2017). The comparative politics of transnational climate governance. International Interactions, 43(1), 1–25.

Røttereng, J.-K.S. (2018). The comparative politics of climate change mitigation measures: Who promotes carbon sinks and why? Global Environmental Politics, 18(1), 52–75. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00444.

Sachs, J. D. (2015). The age of sustainable development. Columbia: Columbia University Press.

Schmidt, N. M., & Fleig, A. (2018). Global patterns of national climate policies: Analyzing 171 country portfolios on climate policy integration. Environmental Science & Policy, 84, 177–185.

Skjaerseth, J., Bang, G., & Schreurs, M. A. (2013). Explaining growing climate policy differences between the European Union and the United States. Global Environmental Politics, 13(4), 61–80.

Smit, B., Burton, I., Klein, R. J. T., & Wandel, J. (2000). An anatomy of adaptation to climate change and variability. In S. M. Kane & G. W. Yohe (Eds.), Societal adaptation to climate variability and change (pp. 223–251). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Sprinz, D. F., & Vaahtoranta, T. (1994). The interest-based explanation of international environmental policy. International Organization, 48(1), 77–105.

Sprinz, D. F., & Weiß, M. (2001). Domestic politics and global climate policy. International Relations and Global Climate Change, 67, 94.

Steves, F., & Teytelboym, A. (2013). Political economy of climate change policy. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2456538, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY.

Tobin, P. (2017). Leaders and laggards: Climate policy ambition in developed states. Global Environmental Politics, 17(4), 28–47.

Tosun, J., & Guy, P. B. (2020). The politics of climate change: Domestic and international responses to a global challenge. International Political Science Review, p 0192512120975659. ISSN 0192-5121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120975659.

UNFCCC. (1992). United Nations framework convention on climate change. New York: United Nations, General Assembly.

UNFCCC. (2009). Decision 2/CP.15: Copenhagen Accord. Technical Report FCCC/CP/2009/11/Add.1, UNFCCC, Copenhagen, Denmark.

UNFCCC. (2016). 2016 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows Report. UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, Bonn, Germany: Technical report.

UNFCCC. (2017). UN Climate Press Release: Bridging Climate Ambition and Finance Gaps. UNFCCC.

UNSD. (2018). UNdata | record view | Table 2.4 Value added by industries at current prices (ISIC Rev. 4). http://data.un.org/Default.aspx.

Van Deveer, S. D., & Steinberg, P. F. (2013). Domestic institutions and actors. In P. G. Harris (Ed.), Routledge handbook of global environmental politics (pp. 150–163). England: Routledge.

Weikmans, R., & Roberts, J. (2019). The international climate finance accounting muddle: Is there hope on the horizon? Climate and Development, 11(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410087.

Weiler, F., Klöck, C., & Dornan, M. (2018). Vulnerability, good governance, or donor interests? The allocation of aid for climate change adaptation. World Development, 104, 65–77.

World Bank. (2018a). Population in millions. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.

World Bank. (2018b). GDP per Capita (Constant 2010 US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University. The research leading to these results was funded by PhD program funding of the Department of Government at Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

The study did not involve human or animal subjects and did not entail informed consent issues.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peterson, L. Domestic and international climate policies: complementarity or disparity?. Int Environ Agreements 22, 97–118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-021-09542-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-021-09542-7