Abstract

The advent of ‘Peace Parks’ on the African continent is puzzling from the perspective of institutional theory. We focus on the world’s largest transfrontier conservation cooperation that exists to date, the Kavango–Zambezi Treaty, which was ratified by Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe in 2011. The collaboration seeks to foster sustainable governance of resources in the region. The paper asks two questions: What were the main factors facilitating the establishment of the Kavango–Zambezi Treaty? What potential challenges for the treaty remain on the operational level? Analysing interviews with key informants, we contribute by providing insights regarding the emergence and existing challenges of the treaty. Factors reducing coordination problems during the treaty’s establishment included that it did not compete with existing institutions at the international level, the important role played by moral authorities such as Nelson Mandela, and that consensus rather than conflict prevailed between respective political actors as they realized the function of this cooperation. The treaty is challenged by differences in macro-institutional factors amongst participating nations and a variation in the extent to which communities trust in and comply with these institutions. There are significant remaining obstacles with regard to harmonizing policies in the five partner countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A coalition of interests has in recent years promoted transboundary governance of natural resources which has led to the emergence of a number of regional environmental treaties, and this has been the most accentuated in sub-Saharan Africa. While some interpret this as the outcome of a discursive struggle where a ‘fences and fines’ approach has come to replace the community-based natural resource management paradigm (Büscher and Whande 2007; Benjaminsen and Svarstad 2010), others see it as a recognition of the complexity of environmental problems and as a way in which levels of governance are matched to the scale of the problem to be addressed (Schoon 2013; Sandwith et al. 2001). This article argues that in order to understand the evolution of treaties that formalize transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs) in African countries—and their continued existence—the role of institutions needs to seriously be taken into account. In fact, the very existence of transboundary conservation initiatives, or ‘Peace Parks’ as they are known in an African context, is quite puzzling from an institutional perspective.Footnote 1 While we know that institutions are important for sustainable natural resource management (Ostrom 2010), the notion of transboundary arrangements highlights a number of theoretical puzzles related to institutional creation and reproduction. That is, most effort has been devoted to investigating the effects of different institutional arrangements. Questions related to why and how institutions emerge in the first place or how they are reproduced and live on—including which challenges they face—have at least partly been neglected (see Thelen 1999; Pierson 2000, 2004).

The purpose of this paper is twofold; to critically explore the emergence of, as well as possible challenges associated with, treaties that structure transboundary natural resource governance from an institutional perspective. This is done through an in-depth case study of the Kavango–Zambezi (KAZA) Treaty, building on interviews with key elite informants. The KAZA transboundary area is the largest and arguably the most ambitious TFCA in the world. It covers 520,000 km2—an area larger than Spain—and is shared by Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The KAZA Treaty was signed in 2011, and although it is relevant for other TFCAs—as well as for our understanding of international environmental agreements and transboundary cooperation and collective action more generally—KAZA’s institutional evolution and institutional dynamics have rarely been analysed in empirical research. Building on existing theories about the dynamics of institutional creation and reproduction, the two questions addressed in this paper are the following: What were the main factors facilitating the establishment of the KAZA Treaty? What potential challenges for the treaty remain on the operational level?

2 Institutions and natural resource management

The literature largely suggests that institutions have the potential to solve collective action dilemmas and foster sustainable use of natural resources. Following seminal contributions from Hardin (1968) and Ostrom (1990), there is now a consensus holding that open access regimes make every resource user expect that others are overharvesting and for that reason they engage in overuse themselves. This is the well-known tragedy of the commons, also conceptualized as a social trap or as the prisoner’s dilemma (c.f. Olson 1965). In these conceptualizations, the expectation that others will embark on a non-cooperative path and free ride on conservation efforts tends to make individual actors reluctant to conserve the collective good or employ a cooperative strategy themselves, even if this would have been rational. Yet, research also shows that institutional arrangements can regulate the sustainable use of resources (Greif 2006). In the absence of such arrangements, however, interactions and exchange come with costs and coordination problems since actors cannot be certain to reap the potential returns and will have difficulties in interpreting the actions of others.

Yet, while we know that institutions can coordinate actors at the local level, we know less about the prospects for collective action at a larger scale. Related, a literature identifies that a similar challenge indeed faces governments involved in international environmental agreements: such treaties hold the potential to be institutions that coordinate involved states’ behaviour, such as reducing pollution or overexploitation of jointly governed resources (Ostrom 2010; Balsiger and Prys 2016).

However, regardless whether the institutions are designed to foster collective action amongst resource users or amongst nations the so-called second-order collective action dilemmas involved in establishing and sustaining such institutions in the first place are generally overlooked. That is, while every actor would benefit from institutions solving collective action problems, this benefit would accrue even if the actors do not contribute to the existence of these very institutions. The calls from many scholars and policymakers for better-designed institutions—as well as the general focus on institutional design—hence risk being in vain or at least being built on simplified assumptions about institutional creation and reproduction (Sjöstedt 2015). Becker and Ostrom (1995: 116) recognize this as they acknowledge that free-riding tends to not only take place in respect to the collective good themselves but also in respect to ‘the set of rules (and their monitoring and enforcement) that would enable individuals to achieve a sustainable long-term utilization pattern in relationship to a resource’.

Moreover, most accounts of institutional creation tend to be highly functionalistic and voluntaristic. Institutional creation tends to be understood as an intentional design exercise where formal rules are selected through a centralized process of bargaining and political competition, or even conflict. The process may also be decentralized in the sense that formal or informal rules are selected through an evolutionary competition amongst alternative institutional designs (Kingston and Caballero 2009). In either case, institutions are ultimately selected, or at least promoted, because they fulfil a certain function. As such, this perspective tends to implicitly assume that institutions develop in an evolutionary manner until an optimal match with the transaction they are to govern is reached (Williamson 2000). The effects of institutions are hence seen as explanations to their existence, or as argued by Pierson (2000: 475), ‘the explanation of institutional forms is to be found in their functional consequences for those who created them’. Yet, actors being as purposive or far-sighted as implied by such a logic might be a questionable assumption. In addition, while it may be quite straightforward to show that an institution is fulfilling a specific function for social actors, it is quite another to persuasively show that this function accounts for the very existence of the institution. The institution may, for example, have served one function in the short term but in the longer term come to serve a different function. And the effects from an institution—or its function—may certainly not always be intentional (Pierson 2000).

In addition, the voluntarism inherent in existing accounts of institutional creation has also faced substantial critique. While most accounts of institutional creation are framed as voluntary agreements that make everyone better off, powerful actors often constrain the choice set of others, and even if complying with a certain institution makes the less powerful better off than not complying, it does not necessarily make them better off than had the powerful actors never established the particular institution in the first place: ‘They must now choose from the power-constrained choice set and from that alone. They may (and probably will) choose to ‘cooperate’. But they may also be worse off than before the institutions were imposed’ (Moe 2005: 227). As forcefully argued by Moe, power hence worms its way into the very foundations of ‘voluntary’ choice.

More recent work within the field of historical institutionalism has, however, made great contributions in respect to incorporating an analysis of power, which provides insights into processes of institutional creation and reproduction. For example, Mahoney and Thelen (2010) explicitly conceptualize institutional dynamics as determined by distributional struggles occurring when problems of rule interpretation and enforcement open up space for actors to implement existing rules in new ways. Institutions, in this account, are conceptualized as being fraught with tensions. Because any given institution has implications for resource allocation (some are even designed with the purpose of distributing resources to particular groups of resource users), institutions can thus be described as ‘distributional instruments laden with power implications’ (Mahoney and Thelen 2010: 8; see also Sjöstedt and Sundström 2015).Footnote 2

However, although the political nature of institutional creation is increasingly recognized, institutional theory tends to display only a crude understanding of political processes in general and the policy process in particular, and as such runs the risk of being politically naïve. This potentially applies to the research on governance of transboundary resources as well. In this field of research, there are, for example, many calls for ‘better-designed institutions’ (Walker et al. 2009) or calls for finding the ‘optimal design for capable institutions’ (Reischl 2012). Yet, we argue, the search for optimality is questionable—not least because optimality only can be assessed in retrospect. Establishment of these conservation areas is obviously a collective action problem in itself as many different actors need to be consulted and involved into the process. This in turn makes it harder to organize, agree on, and enforce common rules (Muchapondwa and Ngwaru 2010; Ostrom 2010). As such, the research on transboundary governance risks holding unrealistic expectations on the possibility of rational and purposeful institutional design for achieving sustainability-enhancing changes in governance systems. Duit (2016) labels this a ‘governability paradox’, meaning ‘if it was indeed possible to design, guide, and control processes of social change to the extent that is assumed in many of the policy prescriptions, then there would probably not be any environmental problems to begin with’ (373).

Although the interdisciplinary ambition is commendable (for a discussion, see Clark and Wallace 2014)—and although the institutional literature on the commons certainly has furthered our understanding of the complexity of social-ecological linkages—the complexity and richness of institutional theory risk being insufficiently explored within this field. It can be argued to not give sufficient recognition to the already existing accounts of, for example, institutional change trajectories (Kingston and Caballero 2009; Thelen 1999), the dynamics of path dependence (Pierson 2004; Mahoney 2000), the distributional character of institutions, or the fundamental, political determinants and drivers of institutional design and diversity (Mahoney and Thelen 2010). Taking these aspects seriously—and letting them guide the analysis—this study sets out to explore how institutional creation was facilitated in the case of KAZA TFCA. In addition, the study explores potential challenges to the institutional arrangement’s continued reproduction.

3 The case

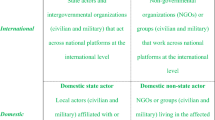

This study focuses on the Kavango–Zambezi (KAZA) Treaty—a partnership and collaboration between Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe supported by Peace Parks Foundation (for a map, see Fig. 1). Peace Parks Foundation is a non-profit organization heavily engaged in promoting and facilitating the establishment of transfrontier conservation areas across sub-Saharan Africa. In the early 2000 s’ ministers from the five countries intensified their collaboration over conservation and tourism development in the region. In 2006, the initial steps towards KAZA TFCA were taken as the countries developed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The MoU outlines that a technical committee should negotiate a draft of a treaty, which a committee of ministers from the five countries shall finalize and present to the respective governments (KAZA 2006). The MoU was preceded by a pre-feasibility study in 2005–2006 (Transfrontier Conservation Consortium 2006; Jones 2008) and in 2008 a document outlining the arrangements for the development of the TFCA was adopted by the responsible ministers. A planning process involving the partner countries then resulted in a first and, thereafter, a second Strategic Plan in 2010 (see KAZA TFCA 2015). Later in 2011, the collaboration was formally established as the KAZA TFCA Treaty was signed. In more detail, this agreement prescribes, for instance, that ‘the five partner states aim to ensure that the natural resources they share across their international boundaries along the Kavango and Zambezi River Basins are conserved and managed prudently for present and future generations within the context of sustainable development’ (KAZA TFCA 2016). Its overarching goal is to sustainably manage the ecosystems and cultural heritage within the region while also enhancing the socioeconomic conditions for the local communities through benefits from conservation and tourism activities (KAZA TFCA 2015). Having its own organizational structure with the Ministerial Committee, the Committee of Senior Officials, the Joint Management Committee, and the National Committee, the collaboration includes both national and transboundary actors at different governance levels. The TFCA is a unique creation, compared to other TFCAs in the region, with a well-developed collaboration which includes a secretariat, staffed with personnel from the participating countries and supported by the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC).

As the largest TFCA in the world, the area holds a variety of tenure and protection schemes with 20 national parks, 85 forest reserves, 22 conservancies, 11 sanctuaries, 103 wildlife management areas, and 11 game management areas (KAZA TFCA 2015). The region further comprises a high density of wildlife with, for example, Africa’s largest unified elephant population (Suich 2012). Simultaneously, there are about two million people living in the region with a third of them residing in unprotected areas (KAZA TFCA 2015). Overall, KAZA TFCA highlights several intriguing governance aspects as the collaboration involves different actors aiming at jointly building and supporting transboundary institutions that both protect wildlife and natural resources, while also promoting benefits to the communities.

4 Method and material

In understanding the drivers behind the creation of KAZA TFCA as well as potential challenges to the sustainability and reproduction of this transboundary collaboration, the study makes use of material from 19 in-depth interviews with elite actors, conducted during February–November 2017.

The informants are both public officials, for instance high-ranking staff at the KAZA secretariat, as well as experts connected to different NGOs that have been or are at the moment engaged in the design, coordination, or management of KAZA TFCA. Other examples of informants include elite actors situated in coordinating positions in law enforcement, actively working to manage poaching-reducing activities in the area, or persons having experience of working as a country liaison in this transnational collaboration. The authors were introduced to the majority of the informants on-site through local contacts, residing and professionally active in Botswana, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. By interviewing elite officials, the aim is to attain valuable information on the management, legal, and organizational structures and also the history and the future of the project. When using interviews with elite actors, researchers often face the difficulty of interpreting what is factual information and what is the person’s perception of historical events (see Marshall and Rossman 2016). We strive to present the insights from our interviews in a transparent manner, therefore often preferring to present longer quotes rather than our own summary of a statement. The sampling of the informants was further based on centrality. Thus, the elite actors are assumed to hold considerable expertise in the field of study since they are currently or previously have been responsible for the planning, coordination, and implementation of projects within the frameworks of KAZA TFCA. The interviews were also used to actively identify further people to meet for in-depth talks, an approach often termed referral sampling or snowball sampling. Four such informants were later interviewed by telephone, because of the distance in their location.

Interviewees were informed about the research project, the purpose of their participation, and the different topics that they would be asked to reflect upon during the interview. This included ensuring confidentiality and that the material would only be applied for scientific use. As the official language for all the partner countries is English, no third party in terms of an interpreter was present during interviews. Generally, at least two authors were present during the face-to-face interviews but one of the persons often took the leading role in posing questions and follow-up queries. Furthermore, all interviews except one were recorded, reducing the risk of errors when transcribing the material.

The interviews were semistructured with a prepared interview guide, comprising open-ended questions, thereby allowing the informant to talk freely about issues and reveal new mechanisms and perspectives that could not be presumed in advance. The informants were first asked about their position and their relation to KAZA TFCA. This was then followed by questions connected to different themes derived from the literature (i.e. international collaboration, national institutions, local strategies and the goals and challenges of KAZA TFCA). The authors sought to find and analyse quotes from the material that explore aspects related to the two research questions guiding this article. As such, we structured our analysis according to the aspects discussed in the theory section; institutional creation, institutional reproduction, path-dependent dynamics, the distributional character of institutions, and general political determinants of institutional design. As the sampling of the informants was purposive, the analysis of the material in turn focused on identifying themes and illustrations, in contrast to applying a statistical approach, which would have been more suitable if there had been a probabilistic sample of respondents.

5 Results and analysis

The following section reports and discusses the insights gained from the interviews with respect to (a) the main factors facilitating the emergence of the Kavango–Zambezi Treaty and (b) what potential challenges for the treaty remain on the operational level.

5.1 The emergence of a treaty

The theoretical discussion above illustrates how institutional creation and institutional change often are processes fraught with tension and characterized by distributional struggles. In the case of regional agreements on transboundary conservation, such friction could intuitively play out in terms of conflicts over the distribution of costs and benefits from tourism and conservation. The transboundary and fugitive resource itself—i.e. a shared resource straddling international borders—could also spur conflicts about harvesting decisions and overall management strategies. Yet, the empirical material highlights at least three crucial factors that initially reduced the severity of second-order collective action problems and helped the involved actors overcome the political tensions and frictions normally associated with institutional creation and evolution. First, the transboundary initiative did not compete with any existing institutional framework at the international level. Mahoney and Thelen (2010) describe how displacement—that is, the removal of existing rules and the introduction of new ones—is often a process fraught with tension and characterized by distributional struggles. The KAZA TFCA, however, did not replace any already existing structure. Even though a regional tourism collaboration, called the Okavango Upper Zambezi International Tourism Initiative (OUZIT), had been initiated between four of the partner countries some years earlier, this initiative was driven by an NGO and was, according to the interviews, not fully recognized by the respective governments. Hence, informants suggest that KAZA TFCA did not challenge any vested interests or path-dependent dynamics at the international level.

It [OUZIT] didn’t succeed because governments felt they had no ownership of this process. And that was… really important to appreciate, that early initiative OUZIT didn’t go terribly well because there was no real government buy-in, no real government ownership. So, back to the drawing board so to speak. (inf. no. 16)

There essentially wasn’t any collaboration. It was an NGO-driven initiative… it wasn’t much collaboration and it actually collapsed. … The thing collapsed because it didn’t have the support of the governments. (inf. no. 16)

Before KAZA there was no cooperation. (inf. no. 16)

A quote from Nelson Mandela—however, not explicitly addressing KAZA TFCA per se—further illustrates the general sentiment that transfrontier institutions did not compete with existing frameworks, but was generally perceived as a win–win solution amongst elite actors: ‘I know of no political movement, no philosophy, no ideology, which does not agree with the Peace Park concept as we see it going into fruition today. It is a concept that can be embraced by all’ (cited in Wolmer 2003). Following this, the role of elite actors as facilitators can be seen as a second essential aspect for how and why KAZA TFCA was created, relating to the discussion about moral authorities. At the time of the emergence of the TFCA, several elite actors and organizations such as the SADC and Peace Parks Foundation seemed to promote the creation of transboundary areas in Southern Africa. The important role played by moral authorities such as Mandela and the window of opportunity that his presidency provided is further illustrated by the following quotes:

There were no obstacles because of Dr. Mandela. He phoned the presidents of the SADC countries and he said that we are coming with an idea. And they all agree that it is a very good idea. … So, there was an idea that was forced down from the top. There was no discussion with communities or anything. They just said ‘we’ll sign’. (inf. no. 19)

Those countries were fully aware that already, they had signed a protocol at SADC regional level, which made provision for creation of cross-border transfrontier conservation areas. So, in 1999 SADC head of states signed a protocol where they recognized that there are parks protected areas which are along the border lines, where the animals move from one area to the other area and those protected areas must be managed as shared resources of protected areas. (inf. no. 3)

Dr. Anton Rupert and President Nelson Mandela were very involved particularly around the eastern sea border between South Africa and Mozambique in initiating transboundary work…. But then the Peace Parks Foundation expanded that to have a SADC-wide vision for the creation of TFCAs within Southern Africa. And it was being developed from top-down, through this political link between Anton Rupert as a business man and a philanthropist and President Nelson Mandela as a patron. (inf. no. 15)

Mandela then gave it momentum. That’s why when President Mandela came into the process, you then started to see the agreements being signed at a rapid speed. And that’s why then you saw the first transfrontier park in Africa signed, which involved South Africa and Botswana. (inf. no. 3)

A third, and closely related, explanation to how and why this particular governance arrangement was created is in fact a functionalistic one holding that the KAZA TFCA could evolve since it fulfilled a desired function for the actors involved. In line with Ostrom’s notion of polycentricity, this treaty can also be conceptualized as an institutional solution that fits closely to the scale of the problem. Because of this, it seems that consensus rather than conflict and power struggles prevailed between respective political actors, as they all realized the function, and in a next step, the potential benefit of managing wildlife and natural resources at the scale of the problem.

At that time, our countries were experiencing that we cannot manage our animals effectively on our own, unless we cooperate. Especially at the border line because animals move from one area to another area. (inf. no. 3)

Well, the objective of establishing KAZA TFCA was based on the fact that it’s one of the corridors in Africa with high density of animals which were transferring from one country to another. … The second objective was to take advantage of that connectivity, geographical connectivity or the movement of game, to promote ecotourism, which would then benefit the five countries that are involved in management of the KAZA TFCA. (inf. no. 3)

The idea behind creating KAZA is that we cooperatively or coordinately manage those resources because there are no boundaries to stop you know, movements … wildlife move you know … freely. So, but, the creation now is to manage the resources together as one park. (inf. no. 11)

I believe this came about as a way of trying to allow animals to live naturally in their natural habitat without boundaries and also to reduce the conflict that comes with these boundaries. Because an elephant is mine today, tomorrow it’s yours because it crosses the boundary, you know, they always do. So, I think that was also a way of trying to manage that conflict between different countries. (inf. no. 18)

Related to this point, one can also understand the fit between the treaty and the scale of the problem as filling a governance void in areas of previously comparatively ungoverned or even ungovernable spaces (Krasner and Risse 2014). The area consists of rather remote border areas where the spatial and societal reach of the involved governments can be assumed to be comparatively low. Yet, in areas of limited statehood there are in fact often functional equivalents to the state making governance work after all. For example, Börzel and Risse (2010) argue that in the absence of the authoritative steering provided by a strong state, either international organizations or strong social norms may in fact often foster coordination, and hence, governance. The evolvement of KAZA TFCA can therefore be seen as a functional equivalent to steering by national governments alone. This equivalent was in turn generally understood by informants to be more effective than previous arrangements.

Transboundary is more effective. I remember that in the last conservation group that we had in Namibia and in Zimbabwe, we identified threats and then you would find that during those sittings, you’d find that almost all the countries were sharing the same thinking. (inf. no. 2)

Transfrontier conservation is actually going to be more effective not only nationally, but in the long term [will] be effective on transnational or transboundary… perspective[s]. (inf. no. 7)

We can no longer think at a national level. That is a thing of the past. Regional planning is critical. (inf. no. 14)

5.2 Remaining challenges for the treaty

Although the treaty seems to be successful in terms of solving the second-order collective action dilemmas involved in institutional creation as well as addressing political conflicts in respect to institutional design, our study also reveals a number of remaining challenges to what in institutional theory is referred to as institutional reproduction.

First, one of the most central challenges facing the KAZA TFCA is that the involved countries differ substantially in regard to macro-institutional factors such as state capacity, government effectiveness, and control of corruption—factors all known to be important in natural resource management. That is, while some states establish institutions that foster collective action and sustainable resource use, most states display substantial shortcomings when it comes to what Mann (1988) calls ‘infrastructural power’ or the institutional capacity to implement their political objectives. In fact, as argued by Slater (2010) many current states even fail to develop a basic monopoly of the legitimate use of force in their territories. Also the countries involved in the KAZA TFCA show huge variation in this regard.

I don’t want to mention any countries here but … we went into this marriage that we call KAZA at different levels. Other countries had been to war, other countries were just recovering from economic problems, social problems, political problems. (inf. no. 7)

Yes of course, different countries have different capacities of enforcing these rules and it goes back again to the same issue of you know that we are not all equal – as much as we are all partners in this, we came in not as equal pairs. (inf. no. 7)

If there is political instability in one country, that obviously is going to affect other countries because more energy will be put in … you know, trying to stabilize the situation in the country while these others are putting in more efforts into the conservation and management of the resources. (inf. no. 11)

While Botswana and Namibia show comparatively high levels of state capacity, Angola and Zimbabwe have suffered from long periods of political decay and ineffective rule. This variation potentially produces a severe challenge to the implementation of the KAZA treaty. In fact, even though research has revealed that resource users are often able to manage resources sustainably, these local-level arrangements potentially depend critically on the surrounding institutional framework (Ostrom 1990). As discussed above, individuals are assumed to seek guidance in institutionalized rules, which not only help actors predict the behaviour of other people but also determine their own interests and define appropriate actions (Greif 2006). These institutions can often operate on the local level but during times of turbulence or stress, local arrangements depend upon the macro-institutional framework in which they are nested. Research has, however, been ‘[relatively negligent in examining how] the external social, physical, and institutional environment affect institutional durability and long-term management at the local level’ (Agrawal 2001: 45). The variation in macro-institutional quality amongst the countries involved in the KAZA TFCA hence remains a challenge that will potentially affect its long-run effectiveness. As illustrated by quotes from the informants, these differences in turn seem to accentuate coordination problems as they affect the expectations on the behaviour of others.

I think it is equally strong [the commitment of the involved states], but obviously there is a concern that some other countries are not doing enough and that is also an issue of the capacity that they have. (inf. no. 6)

It can affect their own commitment because if you get into a partnership and say that ‘these are the shared resources that we want to protect’, you need to put in the same effort and that is a current concern that has been raised by Botswana, that it doesn’t seem that our partners are doing the same effort in conserving this wildlife and resources that we are sharing. We are putting [in] so much resources but when animals cross over to your side they are not protected, they are hammered. (inf. no. 6)

Recently some of the countries that only paid last year, they are now complaining that these other ones, why are they not paying? (inf. no. 10)

Second, the variation in macro-institutional quality also produces substantial challenges as regards enforcement and compliance with respect to the rules and regulations of the KAZA TFCA. On the one hand, it directly affects the material resources available for wildlife management and administration as well as for monitoring, control, and surveillance. An additional, and potentially more severe, challenge is the resulting varying levels of social control and potentially different abilities as regards fostering compliance with rules and regulations. Amongst other things, the literature on rule compliance shows that such actions are not only determined by material resources and coercive capacities of the state. On the contrary, achieving compliance through coercive means alone is prohibitively costly and may encourage the state to instead aim for so-called quasi-voluntary compliance (Levi 1997). Ultimately, the ability to foster such non-coercive compliance in turn depends upon the state’s infrastructural power and legitimacy (cf. Jackman 1993), which determines the capacity of the state to penetrate social relationships and extract and use resources (see Migdal 2001). The fact that the states involved in the KAZA TFCA differ as regards state capacities hence potentially poses a severe challenge to the long-run sustainability and institutional reproduction of the KAZA TFCA. In some of the partner countries, the state is not necessarily the most legitimate actor in the area, which is illustrated by the following quotes highlighting the important role played by traditional authorities.

In some countries you’d find that the [government] authorities are still lying with the traditional authorities. … It is the traditional authorities who understand the needs of their people. So in most cases where the traditional authorities are the ones who have the right over land, we have not had any problems with regard to complying with the natural resource management policies. But where the state has overruled the traditional authorities and taken control of … issuing the land, we have always seen a lot resistance. (inf. no. 7)

For me, a key entry point into the communities would be through the traditional leaders. That is the key. Because when they speak with their subjects…they listen; they listen to them because those traditional leaders, they are always there. They are different from maybe some political leaders who can come and go. But a traditional leader can be there forever. He is there until he is dead, he is gone. (inf. no. 13)

In addition, differences in terms of governments’ spatial and societal reach also seem to affect the state’s ability to reach out to communities and secure their compliance with rules and regulations.

One of the challenges is really getting the message out there to the communities … on the values of these properties that we are protecting. The land, the animals, the trees and everything else. (inf. no. 8)

But I think it basically comes down to trying to gain their trust, first. You have to gain their trust first and you really have to work hard to explain to them in the simplest terms what they can benefit out of what you are doing and what you want to achieve out of that. (inf. no. 1)

I think you might find isolated cases within the broader KAZA area where communities are involved and where they understand, but I think that on the whole, you might well find that communities are more frustrated than anything else because of the lack of delivery. (inf. no. 15)

The KAZA structures have realized that if they don’t actually win over and have the buy-in of local people, this particular TFCA is not going to work terribly well. … You have got to have the support of your local population and in particular the local rural communities who live side by side with wildlife and all that sort of thing. And then that leads you into the whole question of benefits from wildlife and so on at a local level. (inf. no. 16)

But in the end of the day, community conservation I think is going to be what makes or breaks the long-term success of KAZA. … If you really don’t have communities benefitting from that vision, it’s going to struggle. (inf. no. 16)

The differences in capacities are recognized by the KAZA organization, and substantial efforts have been devoted to harmonizing policies and practices across the borders (KAZA TFCA 2015). Yet, harmonization by itself constitutes a third challenge to the institutional reproduction of KAZA TFCA. More specifically, a lack of harmonization affects the expectations of the behaviour of others and potentially produces severe collective action problems.

The biggest challenge is different national policies. Definitely, each country has its own policy regarding conservation and I believe it’s not the same policy amongst the five countries and that alone is very difficult. Because as much as we have KAZA, we’ve got Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana, Angola, Namibia and they’ve got different policies when it comes to conservation. (inf. no. 18)

It’s not easy to harmonize policies and certainly very difficult to harmonize legislation because each country has its own legal statutes, acts, and so forth. And something to bear in mind while we are talking about KAZA is that each of the five countries thoroughly remains supreme. So, if anything that the five KAZA countries, one or more might want to do, where it takes sovereignty of one of the countries, that won’t flow through. (inf. no. 16)

As long as an offence in Zimbabwe is not an offence in the other countries then the KAZA thing doesn’t work. (inf. no. 11)

So, if one country doesn’t allow hunting and the other does, you see there is a conflict. (inf. no. 3)

I think it is easy to have a dream and even easy to sign a treaty. But to change the laws is very difficult. (inf. no. 19)

When it gets to actual implementation, obviously it’s more difficult than talking. So that’s when you have to commit, that if Namibia wants to allow professional hunting to stimulate rural economies and make conservation relevant to local people, but Botswana doesn’t want to allow the shooting of animals,… then transboundary cooperation can actually be derailed. So, when it gets to implementation it’s much more problematic and that’s why you will have in all TFCAs, you will have this initial enthusiasm and then it will go down. (inf. no. 4)

Overall, these accounts suggest how coordination of policies between the partner countries could be an essential aspect in making this collaboration sustainable on a long-term basis and hence for the reproduction of the transboundary institutions.

6 Conclusion

With the recognition that many of the world’s environmental problems today are at scales beyond the nation state, researchers and policymakers have advocated for the need to match the level of governance to the scale of the problem (Schoon 2013; Ostrom 2010). This idea stems partly from the concept ‘bioregionalism’, asserting that boundaries of protected areas should be drawn around ecosystems, rather than following political boundaries (Wolmer 2003). Thus, efforts to manage fugitive natural resources have resulted in the emergence of a new conservation paradigm: transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs). These areas—which have been the most accentuated in sub-Saharan Africa—aim to increase conservation effectiveness through the collaboration between neighbouring countries regarding natural resources (SADC 2012). Yet, while praised by the international community, these initiatives highlight a number of still unresolved theoretical puzzles related to institutional creation and evolution. This study seeks to contribute to our understanding of how and why transboundary governance institutions evolve and live on and to explore the operational challenges and possible pitfalls associated with the institutional reproduction of this initiative. Naturally, there is great variation in terms of both political and ecological dynamics across the many transboundary conservation initiatives now undertaken, and more comparative and systematic studies are of course called for. Our case study, however, has potential to bring general lessons as well.

With an empirical focus on the KAZA Treaty, this study finds that one of the main factors facilitating the emergence of this transboundary institution is that it did not invoke any resistance from vested interests or already existing institutional arrangements. The KAZA TFCA further enjoyed the backing of strong leadership from Nelson Mandela and other elite actors and organizations such as Peace Parks Foundation and SADC, which seems to have facilitated the implementation process. In addition, the analysis reveals that the KAZA TFCA was perceived to fill a governance void and hence represented an institutional solution that better fitted the scale of the problem to be addressed. With high-ranking political actors acknowledging the effectiveness of transboundary governance and the awareness of the potential benefits that could be derived from the collaboration, this seems to have resulted in a rather frictionless process without any extensive power struggles between the political actors.

An alternative, functional, interpretation of this process could, however, be that the very weakness of the involved states in fact could be part of an explanation to the emergence of a joint governance scheme. That is, while it is certainly intuitively puzzling that states agree on giving up parts of their sovereignty to transboundary governance initiatives, the very weakness of the involved states might in fact provide part of an explanation for this process. This would be analogous to the findings of Migdal (2001) who argues that although state leaders realize that creating political mobilization requires effective national agencies that can implement and spread the state’s set of rules, they might discover that effective agencies and their bureaucracies turn into rival power centres able to channel support and mobilize people towards their own political and personal agendas, which in turn threatens the political survival of the leaders. The creation of the KAZA TFCA can thus be seen as a way to demobilize opposition within the national borders by partly replacing the national agencies with an international one. This interpretation would also be in line with insights from the field of regionalism arguing that nation states in many instances join regional organizations in order to boost their legitimacy domestically (Söderbaum 2015). From this perspective, regional cooperation hence serves as an instrument for national leaders to secure their hold of power.

While a simple functional explanation of the emergence of the KAZA TFCA finds support in the empirical material, the remaining challenges still illustrate that effective implementation and the sustaining of the treaty come with considerable friction and potential conflict. Assumptions about institutional creation and evolution as a bloodless and frictionless and voluntary cooperation amongst equals are hence seriously challenged by the analysis of KAZA TFCA. More specifically, the fact that the involved states show great variation in terms of macro-institutional qualities highlights a number of potential collective action problems where the commitment of one actor is affected by the perceived commitment of another actor. The varying capacities also result in varying abilities to foster compliance and gain the trust of the communities living within the area of KAZA TFCA.

Moreover, it is clear from the analysis that KAZA TFCA—as with many other transboundary conservation areas—was a top-down initiative. Yet, while the very creation was reliant on top political actors, its reproduction seems to a large extent to be dependent on local engagements in terms of implementation of regulations and policies on an operational level. Involving the communities concerning, for example, information sharing and co-management thus seems to be another important aspect for this transboundary institution to be sustained. Finally, the lack of policy harmonization potentially affects resource users’ willingness to comply with the rules and regulations of KAZA TFCA. For example, the fact that hunting is allowed on one side of a border but not the other was generally perceived to cause resentment and reduce the overall effectiveness of the transboundary initiative.

In conclusion, the findings from this study imply that TFCAs seem to represent a solution that better fits the scale of the problem. In turn, key actors perceived this solution to be more effective than previous solutions and it seems not to clash with already established institutional arrangements or path-dependent dynamics at the transboundary level. However, the fact that the involved states differ substantially in terms of state capacities seems to produce a number of remaining challenges on the operational level pertaining to expectations on the behaviour of other actors, both amongst states and amongst resource users. While our study primarily has focused on elite actors, it is our firm belief that the longevity and success of transboundary initiatives also depend critically on the participation of local communities and resource users. One of the main takeaway messages is hence that in order to effectively sustain and develop the transboundary initiative, more effort needs to be devoted to policy harmonization as well as to the strengthening of state capacity and legitimacy in the eyes of communities and resource users. In developing our understanding of institutional evolution and reproduction, future research would gain a lot by focusing on other transboundary initiatives. For example, since the establishment of KAZA TFCA was led by the political elite, the field could further be advanced by focusing on cases where transboundary governance has evolved through local initiatives.

Notes

While recognizing that there exists numerous institutional perspectives—with contrasting assumptions regarding, for example, rationality and preference formation—this article builds most strongly on historical institutionalism which is eclectic in the sense that it incorporates traits from both rational choice and sociological institutionalism (Thelen 1999).

Mahoney and Thelen (2010) discuss the concepts of displacement, layering, drift, and conversion. While displacement is defined as the removal of existing rules and the introduction of new ones, layering is a process characterized by the introduction of new rules on top of or alongside existing ones. Drift describes a process where the impact of existing rules changes because of changes in the surrounding environment. Finally, conversion describes the changed enactment of existing rules because of their strategic redeployment.

References

Agrawal, A. (2001). Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Development, 29(10), 1649–1672.

Balsiger, J., & Prys, M. (2016). Regional agreements in international environmental politics. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(2), 239–260.

Becker, C. D., & Ostrom, E. (1995). Human ecology and resource sustainability: The importance of institutional diversity. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 26(1), 113–133.

Benjaminsen, T. A., & Svarstad, H. (2010). The death of an elephant: Conservation discourses versus practices in Africa. Forum for development Studies, 37(3), 385–408.

Börzel, T. A., & Risse, T. (2010). Governance without a state: Can it work? Regulation & Governance, 4(2), 113–134.

Büscher, B., & Whande, W. (2007). Whims of the winds of time? Emerging trends in biodiversity conservation and protected area management. Conservation and Society, 5(1), 22.

Clark, S. G., & Wallace, R. G. (2014). Integration and interdisciplinary: Concepts, frameworks, and education. Policy Sciences, 47(4), 233–255.

Duit, A. (2016). Resilience thinking: Lessons for public administration. Public Administration, 94(2), 364–380.

Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the path to the modern economy: Lessons from medieval trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248.

Jackman, R. W. (1993). Power without force: The political capacity of nation-states. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Jones, B. T. B. (2008). Legislation and policies relating to protected areas, wildlife conservation, and community rights to natural resources in countries being partner in the KAZA TFCA. Windhoek: Conservation International.

KAZA. (2006). Memorandum of understanding concerning the establishment of the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area. Gaborone. Signed 6th December, Victoria falls, Zimbabwe.

Kaza, T. F. C. A. (2015). Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area—Master integrated development plan 2015–2020. Botswana: Kasane.

KAZA TFCA. (2016). About KAZA. https://www.kavangozambezi.org/index.php/en/about/about-kaza. Last Accessed 11 December 2017.

Kingston, C., & Caballero, G. (2009). Comparing theories of institutional change. Journal of Institutional Economics, 5(2), 151–180.

Krasner, S. D., & Risse, T. (2014). External actors, state-building, and service provision in areas of limited statehood: Introduction. Governance, 27(4), 545–567.

Levi, M. (1997). Consent, dissent, and patriotism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and society, 29(4), 507–548.

Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. A. (2010). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mann, M. (1988). States, war and capitalism: Studies in political sociology. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (2016). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Migdal, J. S. (2001). State in society: Studying how states and societies transform and constitute one another. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moe, T. M. (2005). Power and political institutions. Perspectives on politics, 3(2), 215–233.

Muchapondwa, E., & Ngwaru T. (2010) Modelling fugitive natural resources in the context of transfrontier parks: Under what conditions will conservation be successful in Africa? Working Paper No. 170. School of Economics, Cape Town.

Olson, M. (1965). Logic of collective action. Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 550–557.

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267.

Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Reischl, G. (2012). Designing institutions for governing planetary boundaries—Lessons from global forest governance. Ecological Economics, 81, 33–40.

Sandwith, T., Shine, C., Hamilton, L., & Sheppard, D. (2001). Protected areas for peace and co-operation. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 7. Gland: IUCN.

Schoon, M. (2013). Governance in transboundary conservation: How institutional structure and path dependence matter. Conservation and Society, 11(4), 420.

Sjöstedt, M. (2015). Resilience revisited: Taking institutional theory seriously. Ecology and Society, 20(4), 23.

Sjöstedt, M., & Sundström, A. (2015). Coping with illegal fishing: An institutional account of success and failure in Namibia and South Africa. Biological Conservation, 189, 78–85.

Slater, D. (2010). Ordering power: Contentious politics and authoritarian leviathans in Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Söderbaum, F. (2015). Rethinking regionalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Southern African Development Community (SADC). (2012). Transfrontier conservation areas. http://www.sadc.int/themes/natural-resources/transfrontier-conservation-areas/. Accessed 16 April 2018.

Suich, H. (2012). Tourism in transfrontier conservation areas: The Kavango–Zambezi TFCA. In A. Spenceley (Ed.), Responsible tourism: Critical issues for conservation and development. London: Routledge.

Thelen, K. (1999). Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 2(1), 369–404.

Transfrontier Conservation Consortium. (2006). Final report: Pre-feasibility study of the proposed Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area. Stellenbosch: PPF.

Walker, B., Barrett, S., Polasky, S., Galaz, V., Folke, C., Engstrom, G., et al. (2009). Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science, 325, 1345–1346.

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 595–613.

Wolmer, W. (2003). Transboundary conservation: The politics of ecological integrity in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. Journal of Southern African Studies, 29(1), 261–278.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Linell, A., Sjöstedt, M. & Sundström, A. Governing transboundary commons in Africa: the emergence and challenges of the Kavango–Zambezi Treaty. Int Environ Agreements 19, 53–68 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-018-9420-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-018-9420-2