Abstract

When do states allow nonstate actors (NSAs) to observe negotiations at intergovernmental meetings? Previous studies have identified the need for states to close negotiations when the issues under discussion are sensitive. This paper argues that sensitivity alone cannot adequately explain the dynamic of closing down negotiations to observers. Questions that have received little attention in the literature include which issues are considered sensitive and how the decision is made to move the negotiations behind closed doors. This paper examines the practices of NSA involvement in climate diplomacy from three analytical perspectives: functional efficiency, political dynamics, and historical institutionalism. Based on interviews and UNFCCC documents, this paper suggests that to understand the issue of openness in negotiations, institutional factors and the politics of NSA involvement need to be better scrutinized. The paper shows that each perspective has particular advantages when analyzing different dimensions of the negotiations, with implications of how we understand the role of NSAs in global environmental governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nonstate actors (NSAs)Footnote 1 are a significant feature of the landscape of international diplomacy. NSAs are granted access to most major intergovernmental organizations and increasingly participate in international treaty-making processes (Steffek and Nanz 2008; Tallberg and Jönsson 2010; Willetts 2000). The importance of NSAs in global governance discourse is manifested through a growing emphasis on their roles in the academic literature and policy documents (Okereke et al. 2009; Pattberg and Stripple 2008; Willetts 2000). However, discourses are also maintained and transformed by their practices (Winther Jørgensen and Phillips 2002). To understand the role of NSAs, we need to analyze the ways in which they are involved in governance. This article contributes to the analysis of NSAs by examining the practices of involving or excluding these actors from intergovernmental meetings in the realm of climate diplomacy.

A focus on practices helps us to assess the conditions for realizing normative claims about NSAs’ contributions to global governance. There is a prominent discourse on how increased NSA involvement addresses a democratic deficit in global governance (Scholte 2004; Steffek and Nanz 2008; Tallberg and Uhlin 2011). NSAs, such as international nongovernmental organizations and grassroots groups, are expected to contribute to a more pluralized form of global governance (Cerny 2010). However, NSAs’ roles in global governance are dependent on states granting them a supportive participatory environment.

While much of the literature has focused on the granting of formal accreditation (i.e., registration) rights for NSAs to attend intergovernmental proceedings, NSA participation in intergovernmental affairs can be hampered by various informal practices (Depledge 2005). In particular, states retain the right to hold closed-door meetings as they see fit, even in some of the most open international organizations, thereby reducing the opportunities for NSAs to engage in international policy-making.Footnote 2 This raises the interesting question of why states choose to hold certain meetings at intergovernmental negotiations in the open, while other meetings in the same proceedings are held behind closed doors.

Previous studies have noted that states prefer to close negotiations when the issues under discussion are sensitive (Depledge 2005; Raustiala 1997; Stasavage 2004). This paper, however, argues that the sensitivity explanation alone does not adequately explain the dynamics of closing negotiations to observers. Questions that have received little attention in the literature include which issues are considered sensitive by whom, and how the decision is made to move the negotiations behind closed doors. As a first step in analyzing these questions, this paper examines explanations in the literature of why certain negotiations are held in open sessions, while others are closed to NSAs. Our empirical case examines one of the most open international regimes—the international negotiations on climate change under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The aim of this paper is thus to analyze the practices through which NSAs accredited to an intergovernmental meeting are allowed to participate in actual negotiations, which affects their ability to engage in global governance. Based on observations of UNFCCC negotiations, interviews with participants, and a review of UNFCCC documents and secondary material, this paper examines the explanatory value of traditional analyses of participation. Specifically, it examines the functional efficiency perspective, the political dynamics perspective, and historical institutionalism. By confronting these theoretical frameworks with empirical evidence from NSA participation in the UNFCCC, the paper contributes to a more nuanced understanding of factors affecting NSA participation in intergovernmental negotiations, while providing a detailed study of the role of NSAs in climate diplomacy that goes beyond the official rhetoric.

2 Understanding openness in international organizations

Why do states increasingly invite NSAs to participate in the work of intergovernmental organizations? To many observers of international affairs, patterns of NSA access to intergovernmental fora have appeared arbitrary and ad hoc (Albin 1999; Betsill 2008; Susskind 1994). There is now a body of literature, however, that tries to explain this uneven pattern of access. The dominant perspective maintains that states open up for NSA participation in intergovernmental organizations when it is functionally efficient (Raustiala 1997; Steffek 2008; Tallberg 2010). This perspective highlights the services that NSAs can provide to states in the form of resources and skills. States can choose to involve NSAs to increase their own regulatory powers, as NSA participation “provides policy advice, helps monitor commitments and delegations, minimizes ratification risk, and facilitates signaling between governments and constituents” (Raustiala 1997, 720). In sum, this perspective holds that NSAs are granted the right to participate in intergovernmental fora due to rational decisions by states based on considerations of functional gain. The functional efficiency perspective has been used to understand differences in NSA participation across policy areas and policy phases (see, e.g., Steffek 2010), but less is known about how well it explains differences of NSA participation within policy phases.

For example, a general view of functional efficiency holds that across the policy cycle,Footnote 3 states have technical and political incentives to engage NSAs in policy phases such as agenda-setting and implementation and monitoring phases (where NSAs can provide expertise and resources), but not in the decision-making phase. In fact, it is maintained that there may be disadvantages in terms of sovereignty costs in allowing NSA participation at this phase of negotiations (Raustiala 1997; Steffek 2008; Tallberg 2010). However, the literature is less well placed to answer the empirical puzzle of why not all decision-making phases of intergovernmental meetings are held behind closed doors. States regularly hold open meetings even at the decision-making phases. Within an institutional setting (i.e., holding the policy context constant), there can be variation in openness of meetings not only across the policy cycle, but also across issue areas, negotiation stages, and over time if the negotiations continue from year to year (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Official meetings in the UNFCCC daily program during COP/CMP 2010 and 2011 per weekday. Open/closed meetings coded from the daily programs of the UNFCCC meetings of COP16/CMP6 (2010) in Cancún and COP17/CMP7 (2011) in Durban. The daily programs provide an indication of the variation in open/closed meetings during the two week conference

Official meetings in the UNFCCC daily program during COP/CMP 2010 and 2011 per issue area. Open/closed meetings coded from the daily programs of the UNFCCC meetings of COP16/CMP6 in Cancún (2010) and COP17/CMP7 in Durban (2011) per issue area. Informal meetings were coded into the following broad issue areas: Rules of procedures and arrangements for intergovernmental meetings; Kyoto Protocol—LULUCF and numbers (KP); Submissions by parties; Enhanced action on Mitigation; Finance; Vulnerability, adaptation, and response measures; Capacity building; Clean Development Mechanism (CDM); Research and systematic observation; Technology; Joint implementation (JI); Forestry; Shared vision (SV); Education, Training and Public Awareness; Sectoral approaches and various approaches; Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (LCA); Review; National communications and accounting reports (NC). The daily programs provide an indication of the variation in open/closed meetings

The paper argues that this general functional efficiency perspective provides only a limited answer to explaining patterns of when NSAs are allowed to observe meetings within one set of negotiations. The failure to explain these variations in openness may partly stem from a focus on the general motives of states. We must distinguish between motives and procedures: The functional efficiency approach serves to analyze the former, but does not suffice in explaining the empirical observations reported here.

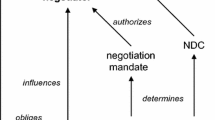

We propose that two other theoretical frameworks—variations in functional efficiency considerations within the negotiations due to political dynamics between states, and the historical institutionalism approach—provide additional explanatory power. Thus, to understand the inclusion of NSAs in intergovernmental negotiations, the roles of states as well as the institutional practice should be considered. Our analytical framework is accordingly guided by two overarching questions: First, why does nonstate involvement vary across policy cycles? Second, how do rules of procedure in intergovernmental organizations influence these decisions? In what follows, we outline the three theoretical frameworks for understanding variation in meeting openness within a given institutional setting and reflect on the comparative advantages of each.

2.1 Functional efficiency, political dynamics, and path dependency

Rational choice institutionalism holds that actors have predefined preferences and act to maximize the realization of those preferences. The functional efficiency explanation, derived from this theoretical framework, holds that NSA participation is not useful when states are embroiled in tough negotiations (Jönsson and Tallberg 2010). Here, the focus is on the services, such as information and expertise, that NSAs as a group offer states at different stages of negotiations. Hence, states would only accept flexible rules of procedures that allow them to conduct closed negotiations at stages when the functional efficiency of secrecy outweighs the functional efficiency of NSA participation.

A first hypothesis that follows from this perspective is that states act instrumentally and decide collectively to hold closed meetings when it is deemed functionally efficient for the process, such as during interstate bargaining. Accordingly, we would expect to find variation in open/closed meetings depending on the stages in the negotiations, such that bargaining stages of the decision-making phase are closed but other parts of this phase may well be open, driven by states’ collective perceptions of sensitivity and functional efficiency.

However, we argue that this general explanation needs to be nuanced by looking at how NSAs’ functional efficiency varies within negotiation phases due to political dynamics. Given that the rules of procedures allow a choice between holding open or closed negotiations, some states may wish to hold open proceedings to score political points in the presence of the NSA community or to add bargaining strength to their position.

The political dynamics perspective is a subset of the rational choice approach in its emphasis on calculated behavior (cf. Tallberg 2010, 56). Though it also seeks to understand participation in terms of motives, its focus is on strategic interactions between states within the institutional context. This perspective follows the functional efficiency explanation in viewing decisions regarding NSA access in terms of cost-benefit analyses, but differs by emphasizing the political considerations of individual states over more service-functionality calculations. The political dynamics perspective thus emphasizes states’ strategic considerations relative to other states.

This perspective assumes that the NSA community is not monolithic and that states’ relationships with this community may vary. In an ongoing round of negotiations, states cannot pick and choose which NSAs to admit to a meetingFootnote 4; nevertheless, the theoretical logic remains that certain states rather than others may have more to gain by letting observers participate in a particular meeting (Tallberg 2010). For example, states may be perceived to have a relative gain in the negotiation when presenting a proposal if that proposal has strong NSA backing. Hence, a second hypothesis is that states strategically seek to influence decisions on open/closed meetings depending on their individual political preferences on particular issues. According to this perspective, we would expect to find variation in whether meetings are open or closed depending on the political saliency of the treated issue.

The functional efficiency and political dynamics perspectives focus on the explicit and implicit motives for NSA inclusion by states. Our analysis will demonstrate that these motives cannot fully explain the decisions to hold open or closed meetings; we also need to analyze the institutional context. To that end, we use historical institutionalism, which emphasizes the role of path dependency in formal and informal rules and procedures in structuring behavior.

The approach of historical institutionalism serves two main purposes in political analysis. First, it underscores the importance of institutions in setting the stage for political behavior. Second, it is used to understand how rules and norms have evolved over time and how they may have affected political outcomes (Steinmo 2008). In our analysis, we use historical institutionalism mainly for the first purpose, as accounting for institutional rules helps us to understand the practices of open and closed meetings.

According to this approach, the institutional setup in which actors operate influences their conduct in a less calculated way. State behavior is structured not by predetermined preferences, as in the rational choice approach, but by routines, norms, and the institutional context. Formal and informal rules structure the “menu of choices available” (Steinmo 2008, 160). Hence, institutional analyses can foster a greater understanding of how rules of procedures shape state behavior at certain phases in the negotiations (Fiertos 2011; Steinmo et al. 1992).

For example, states wishing to restrict NSA participation when they deem issues are sensitive must relate to the institutional framework. While the rules of procedures for intergovernmental meetings are often designed to allow considerable flexibility in how negotiations are conducted, states may not always have clear preferences for open versus closed meetings or states’ perceptions of sensitivity and functional efficiency in the negotiations may diverge. Therefore, some negotiations can alternate between being open or closed, often based on the chair’s initiative without the express consent of all states (Depledge 2005). In other words, the patterns of open and closed meetings also depend on existing operating procedures that have been developed over time rather than solely on the rational choice of states at particular moments in the negotiations. States may well have had an interest in how the rules and procedures were formed but, as time goes by, they become harder to change.Footnote 5

Institutional path dependency therefore restricts state behavior, allowing for only incremental change rather than sudden procedural shifts (Steinmo 2008). A third hypothesis is therefore that both formal and informal rules restrict the action space in which states can advance their interests, as decisions on open/closed negotiations are also influenced by habits and routines. The pattern of open/closed meetings would therefore also depend on institutional factors such as the role of the chair in various negotiation phases.

These propositions will be explored below by examining how the UNFCCC conducts its meetings. After reviewing the role of NSAs in the international climate change negotiations, the subsequent sections will analyze why certain negotiations are conducted behind closed doors, while others are held in the open.

3 Nonstate actors in the international climate change negotiations

The international climate change negotiations conducted under the auspices of the UNFCCC are often considered an open international regime in terms of allowing a multitude of NSAs to attend its conferences and of having relatively generous rules for NSAs concerning access to documentation, making statements, submission of written input, and consultations with the presiding officers and the Executive Secretary (Depledge 2005). The Secretariat also has an NGO-liaison section, which can be viewed as a sign of the deep engagement with NSAs. This relative openness can be attributed to the Convention falling under the policy field of environmental politics and because the negotiations are conducted under the UN umbrella (Linnér and Selin 2013; Morphet 1996; Steffek 2010; Willetts 2000). The fact that the climate change negotiations deal not only with purely environmental issues, but frequently discuss questions of energy, finance, and other issues of high politics, has not detracted from the application of the public participation provisions of the Aarhus Convention.Footnote 6 This testifies to the strong public participation norms in the environmental field that guide the UNFCCC’s open access system.

Nevertheless, interactions between states, NSAs, and the UNFCCC Secretariat have at times been strained, highlighting the importance of going beyond the official rhetoric to study the actual practices of NSA involvement. The handling of NSAs at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP) in Copenhagen in 2009 has been described as particularly damaging (Fisher 2010). After this conference, the issue of observer participation in the UNFCCC was put on the agenda of the Subsidiary Body of Implementation (SBI).Footnote 7 At its 32nd session in 2010, the SBI invited states and observer organizations to submit views on how to enhance the engagement of observer organizations in the UNFCCC process.Footnote 8 In total, five submissions were received from Parties (including one on behalf of the EU) and sixteen from observer organizations.Footnote 9 In these submissions, both Parties with highly divergent political agendas and observer groups stressed the value of NSA involvement in the UNFCCC process and the importance of having participatory and transparent negotiations.

The USA, for examples, writes that “it is important that this process be transparent, and that it allow adequate opportunities for input and exchange of information and views from observers” (FCCC/SBI/2010/MISC.8, 10). Bolivia calls for “full and effective participation of observer organizations” and advocates, as the default, that all negotiations be held in open sessions (FCCC/SBI/2010/MISC.8, 5). The Belgian submission on behalf of the EU also emphasizes the need for transparency, but includes a caveat: It supports the “maximum of transparency of the UNFCCC process, while preserving its effectiveness” (FCCC/SBI/2010/MISC.8, 4). Thus, we can assume that transparency may entail costs and that there could be trade-offs between transparency and effectiveness.

A complex multilateral process, such as the UNFCCC process, has a range of procedures allowing for flexibility in how the negotiations are conducted. For example, the process includes multiple negotiating arenas with different degrees of formality and openness. A range of informal practices has evolved for how these negotiating arenas are to be used. For instance, besides making official decisions, formal plenary meetings are often used to issue official statements and can be employed as a platform for states to posture. Informal arenas, on the other hand, are used to facilitate in-depth discussions and bargaining (Depledge 2005). These informal arenas range from the less informal (e.g., contact groups) to the more informal (e.g., informal consultations, spin-off groups, and “informal informals”).Footnote 10 One change in procedures after COP15 was to indicate in the daily program when closed meetings were scheduled. Looking at two recent climate change conferences (i.e., COP16 in 2010 and COP17 in 2011), we find great variation in open/closed meetings across issue areas, stages in the negotiation, and even between the two conferences (Figs. 1 and 2).

The circumstances under which the negotiations switch between the different arenas and what such practices mean for NSAs, however, have received little attention in the literature. One notable exception is Depledge (2005), who provides an interesting though disjointed account of decisions concerning open/closed negotiations in the UNFCCC. Her focus is on the functional efficiency of secrecy in sensitive stages of the negotiations. We argue, however, that the general functional efficiency perspective does not fully account for which negotiating sessions are considered “sensitive” enough to be closed to observers and why some negotiations in the decision-making phase are held in open sessions despite high political stakes. The general functional efficiency perspective is thus limited beyond explaining the general trend of closed negotiations and cannot account for variation in this trend.

4 Methods

We explore the three perspectives in more detail by analyzing their strengths and weaknesses, drawing on data from interviews, participatory observation, and a review of primary documents and secondary literature. Primary sources include UNFCCC documents covering the issue of observer participation from 2010 to 2011 (see reference list). Observations were made at the climate change negotiations in Bali, Poznan, Copenhagen, Cancún, and Durban (2007–2011) and at two intersessional meetings in Bonn (2011 and 2012). The observations provide an insight into the practice of open/closed negotiations from an observer (NSA) perspective. The interviewees include the current chair of the SBI, Tomasz Chruszczow, his predecessor Robert Owen-Jones, former chief negotiators from India (Surya Sethi), the USA (Harlan Watson), and Sweden (Bo Kjellén), negotiators from Mexico, Denmark, Grenada, Norway, and Bangladesh, as well as seven NSA representatives from the major observer constituencies.Footnote 11 An anonymous interviewee in a position of trust inside the negotiations was also interviewed to verify the information. Interviewees were selected to reflect the perceptions of different negotiating groups covering different issue areas. They were identified as actors in key positions with diverse backgrounds and coming from different regions, with experiences from the negotiation process across a number of years.Footnote 12 Two main questions were considered when analyzing the semi-structured interview material: What are the reasons for wanting to conduct negotiations without the participation of observer organizations? How can Parties operate to move discussions to a closed setting? The analysis used data triangulation, comparing statements from the various interviews and identifying common themes, and then comparing these themes with observations and with analyses of UNFCCC documents (Yin 2009).

5 Explaining patterns of openness in the climate change negotiations

We find three recurring types of patterns in the data: (1) those underscoring the intergovernmental nature of negotiations and a preference by states to close meetings at sensitive stages, thus highlighting the functional efficiency of secrecy; (2) those emphasizing the leverage motives and strategic actions of individual states on certain issues; and (3) those highlighting the rules of procedures, the chairperson’s role, and habit.

5.1 Functional efficiency of secrecy

While NSAs’ contributions to the UNFCCC process are well recognized by both the Secretariat and state Parties, having transparent proceedings at all stages of the negotiations may entail a cost.Footnote 13 In particular, the presence of observers who can report to home constituencies may affect the negotiating tone by, for example, restricting the open exchange of views and leading to the entrenchment of positions, thereby resulting in more arguing than bargaining (Stasavage 2004). Several interviewed negotiators noted that while NSA involvement in international negotiations was important, the nature of intergovernmental negotiations means that certain sessions must be held behind closed doors.

Some emphasized the need for secrecy in the “give and take” and “problem-solving” stages of the negotiations, in which states must make compromises. According to the Norwegian negotiator, there will always be a need for some closed meetings, as “the horse trading is often too ugly for the public eye.” Otherwise, the risk is that states will posture rather than deliberate. For example, according to Thomasz Chruszczow, when “observers are allowed, the Parties are not really, let’s say, behaving how they should behave constructively, getting to the point; sometimes they are just giving long speeches just to demonstrate their devotion, to present themselves.”

Others noted the need for closed meetings to facilitate the airing of views and test the viability of various ideas. This is particularly the case when states do not have clear positions on a question and therefore require the open exchange of views, according to the Mexican negotiator. Several stressed that UNFCCC negotiations are an intergovernmental process and that certain sensitive topics are best discussed behind closed doors. When asked for examples of such topics, the Mexican negotiator cited financial and budgetary issues. This is also consistent with our findings presented in Fig. 2, which indicates that issue areas characterized by quantitative discussions at the COP/CMPs in 2010 and 2011, such as the Kyoto Protocol, finance, and mitigation targets, were the most likely to be closed.

This implies that states perceive a cost in granting NSA access to negotiations at different junctures and therefore prefer to conduct closed negotiations at sensitive stages, such as when the negotiations require difficult compromises, when frank discussions are necessary, and when topics with budgetary implications are discussed. At these times, states perceive that the functional efficiency of secrecy overweighs the functional efficiency of NSA participation. This seems to give the functional efficiency perspective validity in a few select negotiating stages when the political stakes are high.

It also means that the expected pattern of open agenda-setting phases and closed decision-making phases is not necessarily correct. Agenda-setting phases can also be highly sensitive as states fight political battles to include particular items on the agenda while excluding others. Difficult compromises when setting the agenda can mean that sessions move behind closed doors before the adoption of the agenda—as seen in the climate change talks in Bangkok in April 2011 and in Bonn in June 2011. In Bonn, for example, the SBI agenda was discussed in closed, informal sessions for almost 3 days before its final adoption.

In sum, states collectively perceive that the functional efficiency of secrecy outweighs the functional efficiency of NSA participation in particular stages of the negotiations. Such sensitive stages can occur over the policy cycle and are not limited to the decision-making phase, but generally involve stages in which states bargain among themselves. Thus, the general functional efficiency perspective may explain particular cases in which closed negotiations are the result of states wanting to keep the discussions out of the public view. At other times, however, other reasons appear to underlie decisions on closed or open negotiations.

5.2 Political dynamics and leverage

The interests that NSAs represent are diverse and reflect opinions across the landscape of climate politics. Parties can therefore find allies—but also opposition—among the various NSA groups. Because all accredited NSAs attending a conference must be allowed into all open sessions, states cannot pick and choose among NSA groups to only include groups that favor their viewpoint. This means that not all Parties will benefit equally from NSA participation and that some will favor their inclusion in certain sessions as their presence in the room may strengthen their own position or weaken that of the opposition.

The level of NSA interest in the negotiations differs across issue areas, and their positions are often clear to Parties. Certain NSA groups are known to follow particular issues more closely. For example, interviews with NSA representatives indicate that the business sector follows the issue of international property rights with great interest, while forestry issues are followed more closely by environmental groups and indigenous organizations. Therefore, Parties know whether or not NSA participation in a particular session will benefit them. Because NSAs can put different types of pressure on states, some states could gain from conducting proceedings in the open, to expose where opposition to a proposed solution lies. This means that political dynamics can play a role in deciding whether negotiations should involve NSAs, as Parties can lobby to have particular sessions open or closed.

According to the interviewees, some states generally prefer to keep NSAs out of negotiations on principle, while others take a more strategic approach as a way to put pressure on opposing Parties. The Mexican negotiator, for example, stated that Mexico pushed for open negotiations as a general rule in COP16, but that some states opposed this. Other interviewees singled out Saudi Arabia as the country leading the opposition to greater NSA involvement in the negotiations and noted that some developing countries still view NSAs with suspicion. This is not surprising, as most NSAs represented in the UNFCCC (and many other intergovernmental organizations) are Western-based and Western-funded and target countries publicly with criticism, which may not be well-received by countries with closed political systems. Saudi Arabia has been at the receiving end of much criticism from environmental NGOs and was targeted in an incident at the Bonn intersessional meeting in 2010 which was perceived as particularly offensive.Footnote 14 Some countries thus have general political motives for keeping NSAs out of negotiating sessions.

Other countries, however, favor open negotiations as a rule, since they maintain that their positions are already out in the open and that they have nothing to hide. According to Robert Owen-Jones, most Western negotiators believe that it is “easier to do their jobs when people know where the opposition lies.” Similarly, Surya Sethi maintains that the presence of NSAs is beneficial as “they keep other people honest.” Hence, transparency can be used to steer the discussion in a particular direction by relying on the political influence of NSAs to weaken the opposition. While the chair proposes whether a negotiating session is to be open or closed, Parties can lobby to change the decision if they feel strongly about NSAs attending the meeting. According to the anonymous interviewee, opposition to NSAs can come from different Parties at different times and usually “depends on who wants to safeguard that issue.” This is where the political dynamics perspective plays a role, as the decision to hold open or closed sessions is no longer about the general services that NSAs can offer states or the outcome of following standard rules of procedures, but instead results from the strategic calculations of a group of states seeking leverage in the negotiations.

An example of how Parties can push to open informal consultations on particular issues was seen at the Bonn intersessional meeting in June 2011. During an open meeting of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (AWG–LCA), the chair suggested that the negotiations on issues relating to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries (REDD) would be held in informal consultations. The negotiator from Tuvalu, however, objected to holding closed REDD negotiations and stressed the importance of the issue to indigenous groups and that indigenous peoples must be consulted on this matter. While Bolivia agreed with this view, Papua New Guinea and Cameroon opposed the intervention, citing the lack of NSA representativeness and the need to depart from established rules of procedure to question the validity of Tuvalu’s request. However, Tuvalu appealed to the participatory norm, and it was finally agreed that some of the REDD negotiations would be held in open sessions. This exchange illustrates how the political dynamics of the negotiations can give some countries leverage to push for open meetings against the will of other states. While Tuvalu used the participatory norm to advocate opening up the REDD negotiations, the fact that the argument was made only for the REDD sessions implies that a desire for leverage in the issue was the driving force of the intervention.Footnote 15

The political dynamics perspective illustrates how the strategic political considerations of individual states can be a factor in determining whether or not NSAs are granted access to negotiating sessions across issue areas. According to this perspective, NSAs can be used by individual states to increase their own leverage or to weaken the arguments of opponents. This perspective thus accounts for the political game playing between states and groups of NSAs in the intergovernmental negotiations.

5.3 Historical institutionalism: rules of procedure and the role of the chair

While the rules of procedure in the international climate change negotiations offer flexibility in holding closed or open meetings, some rules also limit the policy choices of states. This is most evident when considering the conduct of the closing plenaries of the conferences. Since these plenaries must be held in the open, states can seek to delay them when they have outstanding issues to resolve, but since the conferences must come to a close, there have been many instances of heated open “overtime” negotiations. The final plenary of Durban in 2011 is a case in point: Having dragged on for 36 h because of multiple informal consultations, it offered those who had managed to rebook their journeys home many intense, highly political exchanges.Footnote 16

Another example of how formal rules limit the ability to restrict NSA participation was seen in the final hours of COP15, when the pressure was strong to close the negotiating arena to NSAs (Fisher 2010). Nevertheless, since the plenary shall be open, all NSA constituencies were allowed access to the final stage of heated discussions in the plenary through a small number of self-selected representatives.

These examples illustrate how rules of procedures can constrain states from acting based on predefined preferences in certain negotiation phases. In the above cases, states may have preferred closed negotiations because of the high political stakes, but were guided by established operating procedures, whereby key decisions had to be made in the presence of NSAs. In other words, formal and informal procedures may mean that decisions on open/closed meetings are not always the result of the rational choice of states.

However, rules of procedures can also work to the disadvantage of NSA participation. While NSAs gained access to contact groups (unless one-third of Parties object) through decision 18/CP.4 at COP4,Footnote 17 they do not have access to informal consultations by default. One difference is that contact groups are often open-ended, which means that they are open to participation by all Parties, while other informal arenas can consist of smaller groups of Parties. Time management often means that negotiations are more expeditious in small settings, as these allow more topics to be covered in parallel. Many informal sessions thus only involve a few countries and therefore occur without several Parties in the rooms. Because the number of NSA representatives sometimes exceeds the number of Party representatives at a conference, a general rule to grant them access to such meetings would be unmanageable.

This implies that some closed meetings occur not because NSA presence is considered costly by states but rather because of the habit of negotiating in small groups due to time and logistical constraints. While efficiency is a concern for states, it is the habit of moving negotiations from plenary sessions to small-group settings, regardless of whether or not the issue is sensitive that drives negotiations into informal groups. Agenda pressure was highlighted by several negotiators as a reason for using informal consultations. According to the negotiator from Grenada, “proliferation of topics and limited time means proliferation of informal groups.” Others stressed that many decisions are made in highly informal settings where there is even selectivity in which Parties can attend, implying that closed meetings are not necessarily designed to keep NSAs out, but are instead often used to keep numbers manageable. According to the anonymous interviewee, “to get an agreement you need to restrict the number of people in the room” and “drafting is easier in smaller groups.” These deals must then be brought back to formal fora for consensus decision-making. There are also stock-taking meetings designed to inform other participants (including NSAs) of what is being discussed in the informal sessions. Some meetings are therefore held closed not necessarily to keep NSAs out, but due to standard practice for arriving at deals among key countries.

Moreover, some negotiators and NSA participants noted that the growing number of observers interested in attending the climate change conferences represents a challenge for the arrangement of meeting spaces.Footnote 18 The physical limits of venues mean that the rapid expansion of NSA participation has required careful planning. Several interviewees consider the intersessional meetings in Bonn as being more open to NSAs because of the smaller number of participants. In other words, an increase in NSA participation could paradoxically lead to a more restricted environment for NSA engagement.Footnote 19

Another institutional factor that can affect the level of openness of meetings is the role of the chair. States may not always have a clear predefined preference for whether a meeting should be open or closed to NSAs. At other times, there may be disagreement over whether the meeting should be open or closed. The practice is therefore that the chair of the session has the power to propose the negotiating arena. While the chair may often share states’ views on the functional efficiency of NSA participation at different phases of the negotiations, the role of the chair differs from that of the negotiators, so their views can diverge.

The chair can propose whether an item will be dealt with in a contact group or an informal consultation and, according to the anonymous interviewee, whether a meeting is open or closed can depend on “whether the chair is open or hostile to observers.” The chair also has the power to open informal consultations to NSAs unless Parties object. However, several negotiators noted that informal consultations are rarely open to NSAs because it is not a standard procedure or, in the words of the negotiator from Grenada, “there must be a particular rationale to change the default.” As standard procedures are difficult to diverge from, there is a certain path dependency in closed sessions staying closed. Historical institutionalism can therefore explain why certain negotiations without particularly high political stakes can be closed to NSA participation.

The role of the chair and the importance of rules were also evident in the more open COP17 in Durban. In the previous intersessional meeting in Bonn, the SBI recommended that “at least the first and the last meetings of the informals may be open to observer organizations” if the agenda item has no contact group (FCCC/SBI/2011/7 para. 167). The opening up of informal sessions was advocated by the SBI chair, who did not gain the agreement of all states that, as a general principle, informal consultations should be open to observers when facilitators deemed that it would not impede the negotiations, but managed to drive through this important change in the rules for informal sessions.Footnote 20 The change in practice was observed in Durban, where NSAs were allowed into many more negotiations than in the previous COP in Mexico (55 % open in Durban vs. 28 % in Cancún; see Fig. 1).

Historical institutionalism also sheds light on why certain high-profile negotiations occur in open sessions. The transparency-enhancing role of NSAs may mean that crucial negotiation stages are better performed in the public eye in order to press states to reach an agreement. Since the chair has a mandate to conduct successful negotiations, open negotiations may be viewed as a tool to conclude negotiations in some cases. An example of this could be seen in Kyoto in 1997, when chair Estrada decided to hold the final negotiations in an open session—despite the existence of controversial outstanding issues.Footnote 21 Instead of trying to resolve the outstanding issues in informal sessions, the chair decided to take the negotiations back into the plenary. According to Depledge (2005, 135), this decision reflected Estrada’s wish to “ensure that there would be maximum pressure on negotiators to reach agreement, and that, should any Party seek to block consensus, it would be absolutely clear how and on whose responsibility the Protocol had fallen.”

Historical institutionalism thus adds to a more elaborated account of why certain negotiations are held in open sessions, while others are closed to NSA participation. In particular, it can explain cases of negotiations involving few sensitive issues being closed to observers, while other negotiations with high political stakes are held in open sessions.

6 Conclusion

The proliferation of NSA involvement in intergovernmental organizations has changed the face of international cooperation, as NSAs have gained widespread privileges to participate in previously closed settings. This paper has analyzed the practices under which NSAs are allowed to participate in actual climate change negotiations. When examining why certain UNFCCC negotiations are held in open sessions while others are closed to NSA participation, we found that the dominant functional efficiency perspective focusing on states’ general motives can only account for why some sessions are held behind closed doors. While states may prefer closed negotiations during sensitive stages of the negotiations, such as the bargaining stages, we found that formal and informal rules restrict states’ action space, as decisions on open/closed negotiations are also influenced by standard operating practices, habits, and routines. In addition, states strategically seek to influence decisions on open/closed meetings depending on their individual political preferences on particular issues.

We suggest that the limitations of the general functional efficiency perspective stem from its lack of consideration of the context-specific institutional rules and procedures that structure action and its failure to adequately distinguish between different functions that NSAs can perform. While most of the literature has focused on those NSA functions that are more or less equally valued by all states, such as providing expertise, we suggest that some functions, such as lobbying—for example, in terms of advocating particular issues (e.g., climate justice) or specific policy options (e.g., emissions trading)—can be exploited to the political advantage of individual states. The Party submissions to the SBI on observer organizations reveal that states value different NSA functions, indicating that functionality considerations can be dependent on the political dynamics of the negotiations—a factor often ignored in the literature.

This paper thereby provides a broader basis for understanding why certain negotiating sessions with high sovereignty costs are held in the presence of NSAs, while other sessions with low sovereignty costs are closed to observers. We also provide a more nuanced perspective on the notion that the agenda-setting phases of negotiations are generally open, while the decision-making phases are closed. Moreover, while acknowledging that participatory norms may play a role in driving greater openness, other factors are more likely to underlie such decisions. The functional efficiency, political dynamics, and historical institutionalism perspectives together provide a much more detailed picture of how both motives and procedures together influence how decisions on the type of negotiating arena are made across stages, policy phases, and issues in the negotiations.

What are the implications for NSA participation in intergovernmental organizations in general and the UNFCCC in particular? We have demonstrated that the relationship between states and NSAs in intergovernmental negotiations is complex, going beyond the portrayal of NSAs as a monolithic group of service providers relevant only to certain policy phases. Instead, we suggest that states have varying views on the roles of NSAs in the negotiations and that there is an ongoing process to define their roles in climate diplomacy (Newell et al. 2012). While states remain at the helm of forming practices concerning NSA involvement in intergovernmental processes, the recent change in the rules of procedures in opening the first and last informal consultations to NSAs illustrates how practices can change and make more room for NSA involvement.

The choice of whether negotiating sessions should be open or closed has other implications as well. While a relatively restrictive environment for NSA access does not necessarily mean that NSA representatives are prevented from influencing the negotiations (Betsill 2008; Hjerpe and Linnér 2010; Schroeder and Lovell 2012), it does mean that a large number of closed meetings could skew the influence of NSAs to favor those organizations with strong resources and large networks. This point was emphasized by several interviewees, who noted that some types of NSAs were better equipped to follow negotiations occurring behind closed doors, depending, for example, on previous involvement with the relevant negotiators. Greater restrictions on NSA participation could lead to unequal participation opportunities depending on resources and the further disenfranchisement of particular NSAs (see Fisher and Green 2004). A key challenge is thus to manage a process in which the enhancement of NSA participation leads to greater NSA interest in participation, paradoxically resulting in the introduction of new restrictions (Neeff 2013).

Our analysis has helped distinguish between the motives and procedures shaping state behavior in closed and open meetings. Future studies of other policy areas are needed to provide further empirical data and analysis concerning how this plays out in light of the NSAs’ “demand for” and states’ “supply of” access over time (Steffek 2008). Our study indicates that to account for decisions regarding NSA participation in negotiating sessions, we must look not only at sovereignty costs, but at institutional and political factors as well, since states are faced with various norms, rules, and motives for favoring or opposing the inclusion of NSAs in intergovernmental negotiations.

Notes

We use the term “nonstate actor” to refer to any group that is not a sovereign state participating in global governance, while excluding armed groups. Examples of nonstate actors are nongovernmental organizations, trade associations, and local governments.

While some states include NSA representatives in their delegations, these representatives are often restricted in what they can say and in the information that they can share. This paper is therefore concerned only with the participation of NSA representatives not included in official government delegations.

The policy cycle is here used as an analytical tool to distinguish between different phases of the negotiations. While negotiations may not follow the simplistic path of a policy cycle, the climate change negotiations are often cyclical in nature (Neeff 2013).

The exception is when a state accredits an NSA as part of its delegation, at which point the NSA loses its formal independence and becomes part of the government delegation, thus assuming a different role in the negotiations.

The institutional conditions are often determined through a highly contentious process based on the political dynamics, but once these conditions have been established, all states must relate to them (Depledge 2005).

See for example the UNFCCC keynote speech at MOP 4 of the Aarhus Convention in 2011.

On the role of the SBI, see http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/convention_bodies/items/2629.php and FCCC/SBI/2010/8.

See FCCC/SBI/2010/10.

See FCCC/SBI/2010/16.

For details about the differences between types of informal arenas, see Depledge (2005, 114).

Key representatives of the following constituencies were interviewed: environmental, research, business, trade union, local government, and indigenous peoples’ NGOs.

The interviews were conducted by Naghmeh Nasiritousi between May 2011 and May 2012 and were audio-recorded and transcribed, except for cases where the interviewee asked to remain anonymous.

Author’s observations.

See IISD (2011a, 25).

See Depledge (2005, 210).

The high numbers of NSA participants exceeded the capacity of the venue chosen for COP15. At COP16, the conference was held in two venues with a 10-minute bus ride separating the side events from the negotiations.

After COP15, the UNFCCC Secretariat introduced a registration system that restricts the number of accredited NSA participants in each conference.

See IISD (2011b, 3).

The open plenary was suspended at one point for the chair to consult with the US delegation in private (see Depledge 2005, 135).

Abbreviations

- AWG-LCA:

-

Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention

- CDM:

-

Clean Development Mechanism

- CMP:

-

Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol

- COP:

-

Conference of the Parties

- JI:

-

Joint Implementation

- KP:

-

Kyoto Protocol

- LCA:

-

Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention

- NC:

-

National Communications

- NSAs:

-

Nonstate actors

- REDD:

-

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries

- SBI:

-

Subsidiary Body of Implementation

- SV:

-

Shared vision

- UNFCCC:

-

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

References

Albin, C. (1999). Can NGOs enhance the effectiveness of international negotiation? International Negotiation, 4(3), 371–387.

Bauhr, M., & Nasiritousi, N. (2012). Resisting transparency: Corruption, legitimacy and the quality of global environmental policies. Global Environmental Politics, 12(4), 9–29.

Betsill, M. M. (2008). Reflections on the analytical framework and NGO diplomacy. In M. M. Betsill & E. Corell (Eds.), NGO diplomacy: The influence of nongovernmental organizations in international environmental negotiations (pp. 177–206). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Cerny, P. (2010). Rethinking world politics: A theory of transnational pluralism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Depledge, J. (2005). Climate change negotiations. Toronto, ON: Earthscan Canada.

Dingwerth, K. (2007). The new transnationalism: Private transnational governance and its democratic legitimacy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fiertos, O. (2011). Historical institutionalism in international relations. International Organization, 65(2), 367–399.

Fisher, D. R. (2010). COP-15 in Copenhagen: How the merging of movements left civil society out in the cold. Global Environmental Politics, 10(2), 11–17.

Fisher, D. R., & Green, J. F. (2004). Understanding disenfranchisement: Civil society and developing countries’ influence and participation in global governance for sustainable development. Global Environmental Politics, 4(3), 65–84.

Hjerpe, M., & Linnér, B.-O. (2010). The functions of side events in global climate change governance. Climate Policy, 10(2), 167–180.

IISD (2011a). Earth negotiations bulletin, COP 17, 12(534). http://www.iisd.ca/climate/cop17/compilatione.pdf. Accessed 9 Sept 2012.

IISD (2011b). Earth negotiations bulletin, SB 34, 12(511). http://www.iisd.ca/download/pdf/enb12511e.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2012.

Jönsson, C., & Tallberg, J. (2010). Transnational access: Findings and future research. In C. Jönsson & J. Tallberg (Eds.), Transnational actors in global governance: Patterns, explanations, and implications (pp. 237–252). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Linnér, B.-O., & Selin, H. (2013). The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development: Forty years in the making. Environment and Planning. C: Government and Policy, 31(6), 971–987.

Morphet, S. (1996). NGOs and the environment? In P. Willetts (Ed.), The conscience of the world: The influence of non-governmental organisations in the UN system (pp. 116–147). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Neeff, T. (2013). How many will attend Paris? UNFCCC COP participation patterns 1995–2015. Environmental Science & Policy, 31, 157–159.

Newell, P., Pattberg, P., & Schroeder, H. (2012). Multiactor governance and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37(1), 365–387.

Okereke, C., Bulkeley, H., & Schroeder, H. (2009). Conceptualizing climate governance beyond the international regime. Global Environment Politics, 9(1), 58–78.

Pattberg, P., & Stripple, J. (2008). Beyond the public–private divide: Remapping transnational climate governance in the 21st century. International Environmental Agreements, 8(4), 367–388.

Raustiala, K. (1997). States, NGOs, and international environmental institutions. International Studies Quarterly, 41(4), 719–740.

Scholte, J. A. (2004). Civil society and democratically accountable global governance. Government and Opposition, 39(2), 211–233.

Schroeder, H., & Lovell, H. (2012). The role of non-nation-state actors and side events in the international climate negotiations. Climate Policy, 12(1), 23–37.

Stasavage, D. (2004). Open-door or closed-door? Transparency in domestic and international bargaining. International Organization, 58(4), 667–703.

Steffek, J. (2008). Explaining cooperation between IGOs and NGOs: Push factors, pull factors, and the policy cycle. Paper presented at International Studies Association 49th Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA.

Steffek, J. (2010). Explaining patterns of transnational participation: The role of policy fields. In C. Jönsson & J. Tallberg (Eds.), Transnational actors in global governance: Patterns, explanations, and implications (pp. 67–87). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Steffek, J., & Nanz, P. (2008). Emergent patterns of civil society participation in global and European governance. In J. Steffek, C. Kissling, & P. Nanz (Eds.), Civil society participation in European and global governance: A cure for the democratic deficit? (pp. 1–29). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Steinmo, S. (2008). What is historical institutionalism? In D. Della Porta & M. Keating (Eds.), Approaches in the social sciences (pp. 113–138). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Steinmo, S., Thelen, K., & Longstreth, F. (Eds.). (1992). Structuring politics: Historical institutionalism in comparative analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Susskind, L. (1994). Environmental diplomacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tallberg, J. (2010). Transnational access to international institutions: Three approaches. In C. Jönsson & J. Tallberg (Eds.), Transnational actors in global governance: Patterns, explanations, and implications (pp. 45–66). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tallberg, J., & Jönsson, C. (2010). Transnational actor participation in international institutions: Where, why, and with what consequences? In C. Jönsson & J. Tallberg (Eds.), Transnational actors in global governance: Patterns, explanations, and implications (pp. 1–21). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tallberg, J., & Uhlin, A. (2011). Civil society and global democracy: An assessment. In D. Archibugi, R. Marchetti, & M. Koenig-Archibugi (Eds.), Global democracy: Normative and empirical perspectives (pp. 210–232). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Willetts, P. (2000). From “consultative arrangements” to “partnership”: The changing status of NGOs in diplomacy at the UN. Global Governance, 6(2), 191–212.

Winther Jørgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. London: SAGE Publications.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

UNFCCC Documents (available from http://www.unfccc.int)

FCCC/SBI/2010/8. Arrangements for intergovernmental meetings.

FCCC/SBI/2010/10. Report of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation on its thirty-second session.

FCCC/SBI/2010/16. Synthesis report on ways to enhance the engagement of observer organizations.

FCCC/SBI/2010/MISC.8. Ways to enhance the engagement of observer organizations.

FCCC/SBI/2011/7. Report of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation on its thirty-fourth session.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through generous grants from the Swedish Research Council (Project No. 421-2011-1862) and Formas (Project No. 2011-779) for the research project Nonstate actors in the new landscape of international climate cooperation. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions, and Mathias Friman and Alexandru Grigorescu for constructive comments on a previous version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nasiritousi, N., Linnér, BO. Open or closed meetings? Explaining nonstate actor involvement in the international climate change negotiations. Int Environ Agreements 16, 127–144 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9237-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9237-6