Abstract

While on the surface the Turkish state appears to have asymmetrical power vis-à-vis downstreamers and local societal opponents, and therefore, the ability to shape basin politics, domestic, basin and international protest over the ‘securitised’ Ilısu Dam in Turkey proved more decisive in that respect. A cornerstone of the GAP (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, Southeast Anatolia Project) multi-dam project to harness the water from the Euphrates and Tigris, the dam project elicited successful resistance from Turkey’s downstream neighbours, social and environmental NGOs and professionals targeting the international donors and contractors. On the basis of document research and interviews, this article investigates which factors opened up the space for politicising the project, and how this politicisation played out in both the domestic and international domain. The link between the securitised (where water is almost by default a security issue) and non-securitised spheres of hydropolitical decision-making (where it is not) proved crucial to the success of the anti-dam opposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

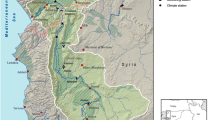

Although the Euphrates–Tigris basinFootnote 1 has frequently been presented as a prime candidate for ‘water wars’ (Starr and Stoll 1988; Bulloch and Darwish 1993), an international war over this scarce resource has yet to happen. Dam building on these rivers, however, has been the focus of domestic strife, interstate threats and international campaigning. The Turkish GAP (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi) multi-dam project has become politicised right from the start. Since 1984, a sequence of dams for irrigation and hydroelectricity has been built on the Euphrates (Firat) River over both neighbours’ objections and radical Kurdish attacks. At the turn of the century, the construction of the Ilısu Dam, the most expensive so far and the first on the Tigris (Dicle), seems to constitute a break in the pattern. The flooding of villages to make room for Ilısu’s reservoir, including the historically important town of Hasankeyf, exposed the projected dam to resistance from a coalition of local, basin and international non-governmental organisation (INGO) groups who managed to stop the flow of external funding of the dam in 2001/2002.

International NGO protest can influence the basin’s balance of power, adding weight to downstream resistance to upstream dam construction. Yet, connecting the domestic and international politicisation of the GAP, notably the Ilısu Dam on the Tigris, shows the contradictions of NGO activism affecting the political process just as relations between the basin states were improving. It is argued that privatisation of the water sector increased Turkey’s permeability to the values of the ‘non-security’ world, whose audience’s acceptance of Turkey’s ‘securitising moves’ (Buzan et al. 1998) was not greater than those of NGO ‘countersecuritising moves’. It is shown that securitisation strategies of various actors, not just state actors, affected and continue to affect the basin’s politics. The article moreover highlights an underexposed divergence of the security discourse and dynamics in the regional ‘hydropolitical complex’ from that played out in the international arena.

The underlying conceptual framework will be explained in Sect. 2. To shed light on the context of the dispute, Sect. 3 sketches a brief hydropolitical history of Turkey’s dam development. After that, Sect. 4 charts domestic and international struggles over river projects, zooming in on the controversy over the Ilısu Dam. Specifically, it asks what opened up the possibility to politicise the Ilısu Dam and its flooding, and how successful it was on the Turkish domestic and international scene. The article ends with a discussion on the securitisation and conclusion (Sect. 5).

The analysis is based on document research and informed by six semi-structured interviews with policymakers and stakeholder representatives carried out during a visit to the GAP area in May 2010.

2 Conceptual framework: securitisation, desecuritisation and countersecuritisation

According to a constructivist perspective of ‘security’, the values security embodies and the dangers that threaten it are not a reality ‘out there’, but constructed problems. Drawing on linguistic pragmatism (Austin 1962), which claims words can create social facts, Buzan et al. (1998) have noted the singular political effect of identifying policy problems as security issues. Presenting an issue as a security issue is a potent way of rallying a political constituency behind a policy. Vital threats such as war and terrorism can be leveraged as reasons for pushing normal rights and rules to one side. ‘Security’ successfully presents a threat as a life-and-death concern (‘securitisation’), legitimising extraordinary measures. In so doing, security speech can change the arena.

Ullmann (1983) noted that traditional low-politics issues such as economics, energy and the environment can become linked with national security issues (high politics). In this context, domestic actors may actively link water issues to high-politics concerns. While it is often northern countries that frame transboundary issues as security concerns, Leboeuf and Broughton (2008) argue that water-poor states have done likewise. The Euphrates and Tigris riparians have likewise resorted to the elevation of water to national security as a consequence of issue linkage with a view to widening or narrowing the power gap between the hydro-hegemon and non-hegemons (Zeitoun and Warner 2006).

The 1990s have seen a debate on the merits of securitisation. Securitisation legitimises extraordinary public measures (top-down decision-making, classifying information, bypassing normal standards of participation and economic valuation) that may benefit the environment but also be environmentally counterproductive. Newman (2009) suggests that the securitised status of an issue fosters environmental degradation more than it otherwise would, but warns that de-securitised (joint) development projects set up in the name of peace can also damage the environment. Fox and Sneddon (2007) likewise picture environmental securitisationFootnote 2 at right angles to environmental/ecological security: jealously guarding state sovereignty ultimately precipitates environmental crises that undermine that sovereignty. To prevent this, they claim that a governance framework is required in which state and non-state actors are roughly equal partners. A transboundary basin could be a ‘new political space’ (Fox and Sneddon 2007: 257).

To understand the relation between transboundary basin politics and security concerns, Schulz (1995) identified Turkey, Syria and Iraq as a hydro-political security complex (HSCs). ‘Security complexes are analytical entities consisting of units displaying distinct patterns of both amity and enmity … surrounded by a zone of relative indifference’ (Buzan 1991). In such a complex, ‘major processes of securitisation, desecuritisation, or both, are so interlinked that their major security problems cannot reasonably be analysed or resolved apart from one another’ (Buzan et al. 1998: 201; Buzan and Wæver 2011: 37). Next to horizontal relations to other HSCs such as Israeli-Palestine, Schulz identified vertical state links to the overlay of global hegemonic games. The present contribution argues that important vertical ties are also traceable to domestic issues.

Securitisation can be a desirable strategy for an impatient policymaker. Given the potency of this effect, it can be tempting to extend the state of exception indefinitely, as has been the case in Egypt since 1980 until it was lifted late January 2012, or to instrumentalise security speech to attain ulterior goals: legitimacy, compliance, control over freedoms, resources and political standing within the bureaucracy. The risk of power abuse has incited Buzan et al. (1998) to favour ‘desecuritisation’: a reframing of issues away from the security domain, into that of normal politics by undermining the ‘felicity’ of the security logic with the intended audience. After all, the success of a security discourse coalition, whether for or against a project, depends on the context and the audience (Balzacq 2005). It takes a receptive audience to validate and ‘instantiate’ a securitising move or alternatively contest the vital threat. The prior relationship between speaker and audience informs the way the audience will respond to the security discourse. The audiences reached (whether intentionally or unintentionally) may be multiple and may include stakeholders outside the securitised territory, who need to be convinced of the exceptionality of the survival issue.

While Buzan et al. (1998) originally stated that securitisation has to come from a position of authority, this view was soon contested: Litfin (1999) and others convincingly claimed that basically everyone can ‘do security’; even from an ‘abject position’, the security have-nots can re-appropriate it for other purposes (Aradau 2004). NGOs and community-based organisations may break normal rules to protect their communities against perceived threats. Thus, others in the policy domain may securitise another value than the original securitising actor identified, in so doing ‘breaking the spell’ of the original securitisation. Such an action may be labelled a ‘countersecuritising move’ (Warner 2011). Table 1 shows in ten easy steps how to securitise and contersecuritisate.

It is argued that these (counter)securitising moves have played a key role in the controversy over Turkish dams on transboundary rivers—not only on behalf of their initiators, to promote the scheme’s acceptance, but also their domestic and foreign opponents. While influential Turkish voices have appropriated the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers as Turkish water for Turkish development and security, with the Turkish state as its legitimate manager (Harris and Alatout 2010), both internal and external opponents have contested this claim. To contextualise this, the background of Turkish dam development is considered next (Table 1).

3 Politicisation and securitisation of the GAP project

3.1 The run-up to GAP

In 1920 the defeated Turkish Sultan Mehmet VI signed the Treaty of Sevres, which lobotomised the Ottoman Empire, a major force since the twelfth century. The Sultan’s abdication in November 1922 established a secular, Europe-oriented republic with a strong role for the military. The new government managed to negotiate a better deal for Turkey in the Lausanne Treaty of 1923: the minorities were not to gain independence, and international control was rescinded.

Post-Ottoman Turkey continued to manifest itself as a regional player. It is historically very well placed at the crossroads between Southeast Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia. Turkey has been a long-time member and cornerstone of NATO and was one of the top three recipients of American foreign aid until the war against Iraq in 2003.

Turkey’s development trajectory was state-led and authoritarian. In the 1930s, Atatürk, father of the Republic, envisaged diverting the Euphrates and Tigris to the drier west of Turkey. This plan gave way to a development vision for the Southeast modelled on the Dniepr development plan in the Soviet Union (Mukhtarov 2009). First studies were conducted in the 1960s, leading to concrete river development proposals in 1970.

In the 1970s, the trade balance of all three Euphrates–Tigris riparians tilted from net food exports to net food imports. An aspiration for autarky spurred Turkey’s internal regulation and resource drive: large irrigation schemes could turn the Southeast into a ‘breadbasket’ for the Middle East. Southeast Anatolia is dry (rainfall ranges between 470 and 830 mm) but rich in fertile soils. Irrigation enables the production of summer crops (cotton, maize, sesame, soybean) which so far was impossible in Southeast Anatolia. In all, the irrigation schemes are scheduled to develop a 2-million-hectare area, an area the collective size of the Benelux countries. The Euphrates is not particularly rich in fish, but this sector is also promoted, especially in the Atatürk Dam reservoir.

At the same time, Turkey’s energy import bill skyrocketed due to OPEC’s energy price hike while domestic demand was on the increase. Annual hydroelectricity production from GAP will produce 22 per cent of Turkey’s total energy generation with an installed capacity of 7,476 MW. The Ilısu HEPP project discussed below is a milestone in this hydroelectric ambition.

After evaluating 22 different combinations of four dams of different heights, the Turkish State Hydraulic Works department, Devlet Su Işleri (DSI), presented the Lower Firat plan for the Euphrates in 1970 to bring irrigation and low-cost energy to the surrounding plains between what are now the Keban and Atatürk dams. In 1977, the Lower Firat plan was integrated into a package with all other schemes in these regions, seven hydropower and irrigation schemes on the Euphrates and 6 on the Tigris, by the name of GAP. In 1983 construction of the project’s centrepiece, the Atatürk Dam, started.

Given the large outlay and uncertainties involved, a Turkish-Japanese consortium was commissioned to draw up a GAP Master Plan, which recommended scaling back the GAP to priority projects (Brismar 2002) but continued its radical reorientation towards a regional development project, people-focussed rather than water oriented in scope. The Master Plan sought to lift the region, seen as backward, in terms of education, agricultural practices, gender relations, environmental conditions and participation. By then the GAP scheme had expanded to 22 dam projects (comprising 80 dams) and 19 hydropower schemes involving 66 hydropower stations on both the Euphrates and Tigris,Footnote 3 providing irrigation for 1.9 million ha and investment in health, education, finance and transportation to modernise a traditional agricultural society in a region twice the size of Belgium (Balat 2003).

Despite its progressive reincarnation, the scheme kept inciting domestic and international allegations that the project was neither sustainable nor peaceful. Downstream states complained about the quantitative and qualitative impacts on their water resources, actors in the Kurdish-inhabited region where the dams are planned saw it as a hostile move to integrate the Kurds into Turkey, while (I)NGOs activist academics and journalists worried about the humanitarian, environmental and cultural heritage consequences of flooding dozens of villages.

3.2 Downstream fear of floods and droughts

The Turkish state’s hydraulic mission not only impacts on the country’s relations with the Southeast, but also the state of play with downstream neighbours. Both the Euphrates and Tigris rivers have great extremes between their highest and lowest flow levels, bringing risk of both drought and floods. The region is also drought-prone, inviting impoundment of water in dams. Downstream states are normally the first to shield themselves from flooding and develop the flatter valley lands, and Iraq is no exception. Flood control can bring many benefits: regulated water supply, agrarian and industrial development and control of territory. Especially in Iraq, floods have historically brought distress and inspired Great Flood accounts like Gilgamesh as well as the biblical deluge recounted in the book of Genesis. This especially concerns the river Tigris: snowmelt from the Taurus and, via its Zap tributaries, Zagros Mountains add their waters causing often destructive flooding. In ancient Mesopotamia, the spring floods were a source of acute fear each year; in recent times, the 1954 flood ravaged the capital, Baghdad. In response, Iraq built the ar-Ramadi and Sāmarrā’ barrages in the 1950s, to divert the floodwaters into Lake Habbaniyah and the Tharthar depression in central Iraq. Even larger works carried out on the Tigris tributaries Zap and Diyala further tamed the Tigris, though the last major Tigris flood is as recent as 1988.

When midstream Syria started developing the Euphrates, Syria and Iraq just stopped short of a violent clash over water in 1976. The Cold War provided an opportunity for Syria to build its Tabqa Dam between 1966 and 1973 with Soviet support. This reduced the flood risk for Iraq, but also curtailed much-needed irrigation water and silt (and, less welcome, salt). Iraq claimed that the dam’s impoundment adversely affected 3 million Iraqi farmers (Starr and Stoll 1988). As a result, in 1975, armed forces of both countries were mobilised at the border. The Arab League had to mediate.

Ever since Syria and Iraq’s wings of the ruling Ba’ath (‘Renaissance’) party split, relations between the two countries have been notoriously bad, and the 1975 clash was the closest the Euphrates riparians have come to violence over water. However, a common cause against a third party can make enemies temporarily set aside their differences and create a joint front. The GAP mega-project provided the occasion for their joining forces and delivering fierce protests and threat to Turkey each time a dam is announced.

Any upstream latecomer inevitably faces a legitimacy problem as downstreamers will claim prior use (Kibaroğlu 2003). The historic Euphrates flow before Turkey started its project is calculated at 1,000 cubic metres per second (m3/s) at the border with Syria. The downstream Arab states argue that since there are three states sharing the river’s flow, each is entitled to one-third, giving the two Arab states a total of around 667 m3/s (Gruen 2004). Turkey could not agree to that amount, but signed a protocol with Syria in 1987 promising to release an average of 500 m3/s, about half the river flow, across the Turkish–Syrian border, and has not flagrantly defaulted.

Frequently, a GAP-induced 40 per cent reduction in river discharge downstream is predicted for Syria and up to 80 per cent less for Iraq; this latter figure would be a cumulative effect of Turkish and Syrian dam projects (Shapland 1997). But more important than the real impact is the potential to give the water tap a twist in either direction. After all Turkish engineers stopped the Euphrates flow for a month to fill the storage lake for the huge Atatürk Dam, in a year where the flow was low anyway (190 m3/s). The Turks declared the decision final and non-negotiable (Zawahri 2008). The two downstreamers pleaded for dam-lake impoundment without stopping the river, but in 1990 President Özal claimed that the Euphrates–Tigris does not have to be shared because it is a ‘Turkish river’. This way, Turkey resisted internationalisation of the water issue, claiming that the water is safest in Turkish hands. Turkey did honour its obligation to supplement the flow later. The Birecik dam, also on the Euphrates, was filled in another dry period, 1999 until 2001. When 2000 carried an extremely low flow of 75 m3/s, Turkey made endeavours to let through 400 m3 (Brismar 2002).

Active storage in Syrian dams would be too small to contain strategic or unintentional mass releases or mass ‘arrests’ of the Euphrates and Tigris. The Turks, however, are investing great effort into trying to convince others that its actions are taken in good faith and serve the interests of the downstream actors as well. The Tigris is more flood prone than the Euphrates—snowmelt in March can cause torrential flooding in April, the harvest month, which necessitated early diking, canalisation and diversion works in Iraq.Footnote 4 The Turkish dams regulate the hydrological regime, so that they not only cushion the impact of floods and droughts downstream but also improve the timing of the river regime to coincide with downstream agricultural needs (Bilen 2000). Turkey, thus, contributes to a stability of expectations that can be regarded as an international public good—but without conferring with its neighbours.

So far, Turkey has laid relatively limited claim to the Tigris, but the final series of GAP dams will significantly enclose that river, too. The first big dam on the Tigris, Ilısu, 1,810 m long and 135 m high, will have a total storage capacity of just under 10.5 billion cubic metres and an operating capacity of 7.5 billion m3. Normally, that would leave a buffer capacity of 3 billion m3. As the average annual inflow of the Tigris is 15 billion m3, the reservoir will account for half the total annual Tigris flow. Opponents fear that the spare capacity would enable a malevolent Turkish government to arrest the river influx for some additional months, such that, they hold, not a drop of Tigris water would flow into Syria and Iraq (Bosshard 1999).

Not just closing but also suddenly opening the floodgates would be disastrous. There is a historic precedent: in 689 B.C. Sennacherib, the Assyrian dammed the Euphrates upstream from Baghdad, only to destroy it after sufficient water had assembled behind the dam. The sudden flood wave flooded the Mesopotamian capital and won Sennacherib the day. According to a Pentagon statement, Iraq itself used strategic flooding of the Tigris to stop Iranian advances in the 1980s, and indeed, there were fears that the river would be used as a defence against the allied invasion in 2003 (CNN 2003). A dam can even break accidentally: half a million citizens in Mosul and Baghdad found themselves at risk from a flood wave if a fragile Iraqi dam should break at Mosul (Independent, 8 August 2007).

When Syria joined the anti-Saddam coalition in the Gulf War, the two countries officially fell out, but after a 5-day meeting in 1996, the states decided jointly to dispatch threatening letters to companies involved in building the Birecik dam. When the Ilısu Dam, a hydropower and irrigation project 45 km from the Syrian border, and its smaller sister dam, Cizre, were mooted, Syria and Iraq again joined forces sending protest letters to funders. Turkey’s upstream development caused the downstream riparians to be sufficiently ‘realist’ to agree in 1996 on a percentage distribution of whatever Turkey leaves them: 42 per cent for Syria and 58 per cent for Iraq.

Until 2008 the downstream riparians have consistently resisted the building of new Turkish dams and maintained the Euphrates and Tigris are international rivers. Iraq and Syria furthermore claim a breach of international law and riparian water rights. This is not a particularly strong hand, though. With some imagination, a breach of a Turco-Syrian treaty stipulating consultation between riparians could be invoked. The Treaty of Friendship and Good Neighbourliness signed in 1946 by Iraq and Turkey was the first real legal instrument for cooperation. It included a Protocol for the Control of the Waters of the Tigris and Euphrates, and their tributaries. The countries agreed that flood control structures and storage services should be built upstream on Turkish territory, which was the most effective location. The Turks promised to provide daily hydrological and meteorological data concerning floods (Gruen 2000). A Turkish–Iraqi Protocol signed that same year allowed Iraq to construct hydrological infrastructure and meteorological stations along the rivers inside Turkey ‘to prevent downriver flooding and, thus, benefit Iraq’ (El-Fadel et al. 2002). But international law only provides only cold comfort for water plaintiffs: there are no widely shared and enforced principles governing international rivers. Iraq may insist on the international law doctrine of absolute territorial integrity, stipulating that no riparian is allowed to impair the quality and quantity of the water resources flowing within its territory. But Turkey can with equal vigour juxtapose the doctrine of unlimited territorial sovereignty, also known as the Harmon doctrine: each state can treat the water within its boundaries any which way it likes.Footnote 5

3.3 Linkage politics and the Kurdish issue

Although Turkish and Arabic groups are also significant in the GAP region, Kurds dominate. Southeast Anatolia is a patchwork quilt of landowners and landless, often groups of nomadic origin which various Ottoman rulers tried to sedentarise with varying success since the seventeenth century. When the dream of independence fell through in the 1920s, the Kurds resisted ‘horizontal integration’ by an assimilative Kemalist republic, staging several uprisings. The republic, in turn, regarded their particularism, but also their aversion to secularism as a threat to Turkish unity. The Turkish Republic was defined as an indivisible, unitary Turkish state in which the Kurds formally existed only as ‘mountain’ or ‘Eastern Turks’ (doğulu). This key plank of the Kemalist scaffolding was enforced in a (recently relaxed) curb on Kurdish identity, language and culture, seeking the cultural homogenisation (Turkification) of an imagined ‘Kurdistan’.

When the resolutely secular Kurdish Workers’ Party arrived on the scene claiming to represent the Kurdish cause in the early 1980s, they did not command an obvious following, but in Leninist fashion, the PKK regarded itself as the uncompromising front guard. In 1984, as construction works for the Atatürk Dam got underway, the PKK staged violent attacks on the dam. Reportedly, 1,100 vehicles and pieces of working machinery were destroyed (Williams 2003). While the PKK did not manage to stop construction, slowing down development inevitably drove up the costs of the project.

Organised along tribal lines (Erhan 1997), Kurdish identity is by no means socially cohesive or culturally unified. But the attacks gave a face to Kurdish aspirations for autonomy. Kurdish parties in Turkish parliament were forced to the denounce PKK, or close down if they did not. The uprising again sparked ruthless response from the Turkish armed forces as well as paramilitary death squads. Both the Turkish Army and the PKK intimidated the villages, the former to smoke out insurgents from villages and forests, the latter to ensure allegiance to their cause.

From the early 1990s, GAP dams officially became an instrument in the ‘fight against terrorism’. State officials argued that ‘terrorists will no longer be able to easily cross from one region to the other due to the dams’. The dam site for Ilısu, for example, is near ‘Hell’s Valley’, famously named for its mountainous corridors used by Kurdish fighters. Opponents therefore claim that the dams seek to block easy passage between Kurdish from the Iraqi and Syrian side; 5,000 Turkish soldiers were reportedly stationed at Ilısu for the period of the construction works (Özok-Gündogan 2005).

Yet, President Özal saw the continuing war and securitisation of hydraulic development as an obstacle to Turkey’s regional ambitions. In 1993 Özal, the PKK and other Kurdish leaders seemed close to coming to an understanding along the lines of a federation, and the PKK called a unilateral ceasefire to end the intifada (Jongerden and Oudshoorn 1997). But after the President passed away, his successor Demirel chose to reinforce the violence against insurgents.

The aspiration for statehood for the Kurdish, dispersed over several countries, makes it an ideal issue for both Turkey and its neighbours to conduct linkage politics. From 1978, Syria used the Kurdish in Syria as a bargaining chip to add force to its water demands. But Turkey could use its upstream position as a bargaining chip, too. When Turkish threats to stop water flows to Syria led to Syrian promises to discontinue their support to the PKK, the resistance movement could use Lebanon’s Biqa’a Valley in Lebanon, then controlled by Syria, as a training ground. In the mid-1990s, Turkey increased its minimum flow pledge to Syria (Daoudy 2009), but Syria wanted more. By 1998, Turkish–Syrian relations came to a head with threats of violence. Syria backed down and handed over Öcalan.

Relations with Iraq on the Kurdish issue show a more complex mix of cooperation and conflict. Before the defeat of Saddam, a key worry for the Turkish state was Iraq’s hegemonic aspirations, especially after his invasion of Kuwait (Aydın 2003). Turkey lent logistic support to the allied invasion of Iraq in 1991 but occasionally needed its neighbour to grant ‘hot pursuit’ of Kurdish separatists on Iraqi territory. Turkey also refused to block Iraq’s river access despite allied requests to do so. It is perhaps indicative of changed basin relations that Turkey no longer allowed its territory to be used as an air base in the 2003 war on Iraq.

3.4 New international players in basin politics

Until 1994 conflicts over the Euphrates and Tigris remained within a neat Realist framework of rivalry between states. However, the privatisation in the Turkish water sector has brought new actors into play from outside the securitised sphere, directly or indirectly influencing basin politics: transnational companies (TNCs), and hot on their heels, INGOs see Table 2 below. The latter’s campaign over human rights and cultural heritage in dam site areas added to the opposition from co-riparians targeted the Achilles heel of a project of this size and scale: funding (Table 2).

Finding external money for GAP has proved problematic for the Turkish government from the start. Although the World Bank formally decided not to fund GAP projects in 1984, the Turkish government apparently never even formally applied for Bank backing, sensing the Bank would show itself highly sensitive to protestations on the part of co-riparians Syria and Iraq.

An inflation-ridden economy groaned under the development effort, coupled with the cost of military engagement with the PKK. The lack of multilateral cooperation made itself felt in ever more painful ways when in the early nineties projects started to fall behind schedule and GAP began to look like the famed ‘white elephant’: the costly development project that never materialises. The GAP, however, could gather steam due to a radical institutional move: privatisation. As early as in 1987, the Izmit dam ran out of funds. Izmit, located close to Turkey’s capital metropolis, Istanbul, was to provide water for homes and industry. At the instigation of President Özal, a private consortium was created, Izmit Su, to complete the works (dam, storage lake, sewage works and water utility). Thames Water was contracted under a Build, Operate and Transfer (BOT) scheme to run the utility for 15 years before returning it to the municipality of Izmit.

While private investment was possible under the 1984 Build-Operate-Transfer law, the required legislative framework and infrastructure simply were not in place.Footnote 6 A privatisation law, opposed by the secular and religious right, was pushed through Parliament in November 1994 by Prime Minister Ciller. As a result, the Izmit project was ready to go onstream 10 years after its abortive start.

Faced with an acute shortage of project funds for the remainder of the GAP project, Turkey needed to co-opt the global jet stream of liberalisation and privatisation in the water sector. While Turkey needed to project a vision of GAP bringing mutual hydraulic benefit to an international audience, if only to secure the flow of funds, privatisation presaged a heated internationalised dispute over the Izmit, Birecik and, most intensely, Ilısu Dam, the first major Turkish dam on the Tigris. Privatisation not only exposed donors and guarantors to public scrutiny, it also ran up against activist (I)NGO strategy calling foreign companies account for their corporate governance practice. Their conclusions were supported by the Government Audit Department, Sayistay, in 1999–2000, who issued a detailed report saying that, from beginning to end, ‘the project was full of violations of laws’. In 2002, after the contract expired, the Turkish Court of Accounts found irregularities in the contract that made the water too expensive (cited in Munir 2004).

For construction companies, the projects do not just provide opportunity but much-needed economic security in a highly competitive market. However, participation in GAP also carried considerable economic and political risk: investing in a controversial project in a country that was effectively still at war with itself. As international companies were loath to carry the risk themselves, the contractors sought to alleviate it by securing export credits from the export credit agencies (ECAs) of Austria, Germany, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States and the UK in Summer 1998. Export credits were especially needed to secure the participation of the British construction company Balfour Beatty, approached by the Swiss-Swedish construction giant ABB (Asea Brown Boveri) to subcontract the civil engineering works while ABB itself took care of the electrical engineering. Sulzer Escher Wyss would lead the construction consortium to realise the dam, the reservoir and hydropower station. Other enterprises involved in the original Ilısu consortium were Impreglio (Italy), Skanska (Sweden) and the Turkish companies Nurol, Kiska and Tekfen.

The international private involvement in Ilısu exposed the companies and their governmental backers to angry Syrian letters and writs against foreign investors and constructors involved in GAP. Syria repeatedly claimed that Turkish interventions damaged Syrian agriculture and water supply. When Ilısu was approved, Syria filed compensation claims from constructing and funding companies, including Chase Manhattan Bank, and threatened to blacklist them until a trilateral agreement was signed.

While such downstream resistance greets the start of any new Turkish dam project, the guaranteeing governments had not counted on the GAP uniting Syria and Iraq (Gulf War adversaries) and (I)NGOs in an alliance of convenience over human rights. This international support for downstream protest was to become a factor in the hydropolitics of the basin.

4 The battle over Ilısu

4.1 The flooding of Zeugma and Hasankeyf

As the funding for Ilısu Dam became a news item in Europe, the Bireck dam, just north of the Syrian border, was also under fire. Started in April 1996 and completed in 2002, filling its reservoir necessitated the flooding of the ancient Roman city of Zeugma in 2000. Labelling Zeugma a ‘second Pompeii’, opponents not just saw this flooding as a tragedy for local history but also for the world’s cultural heritage. The GAP administration (quoted in Shoup 2006) played down the issue noting that the city centre and hundreds of historic villas remain untouched: ‘Turkey has so many [historic] resources that a single one cannot matter’ when the cradle of civilisation gives way to a new kind of civilisation. An indignant editorial on the Birecik flooding in 1996 in the New York Times, however, was reprinted in Turkey and triggered a petition from Turkish archaeologists and architects. A mosaic was salvaged after a US$5 million donation from American billionaire David Packard (Shoup 2006).Footnote 7

For the Ilısu hydropower project, the lower reaches of the coastal town of Hasankeyf will disappear. Eighty-one other heritage sites are similarly facing inundation, including several Muslim and Christian holy sites that are still in use today. Said to be a late Assyrian settlement dating back from the seventh century B.C. and a node of the Silk Road in the Middle Ages, Hasankeyf occupied a strategic position as a fortified castle, controlling the caravan route from Diyarbakir to Mosul in Iraq, and continues to attract pilgrims to the tomb of Imam Abdullah. But because the whole region is so rich in historic architecture, Hasankeyf did not command much special interest until a French historian published on it in the 1940s (Meinecke 1996). In 1969, a study of Hasankeyf was made, and in 1978, Turkey’s Culture Ministry pledged full archaeological protection. In 1981, the site was listed among 22 declared first-class cultural heritage sites. The year before, however, in 1980, an international consortium had been commissioned to draw up a feasibility report for the Ilısu hydroelectricity project and in 1982 the Ilısu Dam plan was ready, including the submersion of Hasankeyf.

The mayor of Hasankeyf moved into a limestone cave in protest against their inundation, while journalists collected dramatic quotes such as ‘My family has been living here for 450 years… they want to extinguish the culture of a 1,000 years for the sake of one burning light bulb’ (in Shoup 2006). Balfour Beatty, however, noted that Hasankeyf was abandoned after the First World War and only re-occupied in the 1960s, claiming that at least some of the history seems imaginary (q. in Shoup 2006).

4.2 Framing the issue

The protest against Ilısu resonated with an ongoing international campaign against large infrastructural projects and their funders that had gathered steam in the 1990s: Malaysia’s Pergau Dam, Nepal’s Arun dam, Lesotho’s Highlands Project and indeed Turkey’s Birecik and Ilısu Dams. Local protest against dams like Arun in Nepal and Narmada was amplified to a global audience by an INGO lobby, making large donors increasingly uneasy about funding. In fact when a Swiss consortium won the Ilısu contract in 1996, it found a well-orchestrated European NGO coalition breathing down its neck.

The Bundesrat, to which the Swiss central bank USB is accountable, justified its export risk guarantee go ahead for 470 million Swiss francs with a view to new Swiss jobs (Bosshard 1999). The Swiss government, however, made its export credit conditional on an independent monitoring mechanism being established.

Casting the GAP flooding and resettlement as a human rights violation and environmental disaster led to parliamentary questions in Germany and Switzerland. The British Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), however, was ‘minded’ to issue a GBP200mn export credit to the project leader, Turkey’s State Hydraulic Works department (DSI) in 1999. DTI’s Export Credit Guarantee Department, which governs export credits, defended the project as a fine example of its ethical policy, claiming that it would contribute to Middle East peace (Guardian 1999).

By recasting the issue as a human rights issue, the opponents could play at a concern which to many is an absolute, existential value at the individual and group level. The repression of Kurdish identity was played by the coalition against the Ilısu Dam on a human as well as cultural rights platform, also drawing on environmental security, the destruction of the ecosystem.

The opponents’ discourse could be quite heavy-handed. Activist archaeologist Maggie Ronayne of Trinity College in Galway, Ireland, called the project a weapon of ‘mass cultural destruction’. George Monbiot, environmental journalist with the British Guardian newspaper, accused Turkey of ‘ethnic cleansing’ (Monbiot 1999) echoed by human rights organisation Göc-Der (Shoup 2006: 250).

While Turkey and the UK foreign office advanced the project as promoting regional peace, journalists like Monbiot and Fred Pearce claimed that the project would spark a ‘water war’ between the basin states, making frontpage news in The Guardian and The Independent newspapers in 1999. A water war proved a much more effective discursive ‘spin’ than cultural, ecological or economic security arguments. The affair was painful to the Labour government which sought to set itself apart from its Conservative predecessor, which some 4 years before had been embarrassed over dubious dealings on a big dam project in Malaysia, Pergau.

When questions were raised in the House of Commons, claiming that the Ilısu’s ‘security implications’ could extend far beyond Turkey’s borders and could affect British security interests as a member of NATO and Turkey’s future in the EU,Footnote 8 the Blair government decided to wash its hands off the project. Hamilton (2003) argues that the desire not to upset regional power balances may well have precipitated British withdrawal from Ilısu.

Activists no doubt hoped that stricter conditions from project backers would mean the end of the project. Turkey, however, went along with opening up the project to international and local scrutiny and environmental accountability. This move promoted an already ongoing project redefinition process. While GAP started in the late 1970 with the intention of reforming the socio-economic situation in the most underdeveloped Turkish region, the project’s objectives have broadened quite a lot in response to recurring criticism. In 1989, the Turkish government established the South-eastern Anatolia Project Regional Development Administration (GAP-RDA) to plan, monitor, report and coordinate with stakeholders to arrive at regional development (Mukhtarov 2009: 180). Headed by Olcay Ünver, many ‘enlightened’ modifications were made, including socio-economic, environmental, educational and participatory facilities as well a more integrated vision of water management. Representative reforms included the establishment of Water Users Associations with farmer representation and decentralisation of decision-making to mayoral level. The GAP administration prides itself on having turned around from a ‘hydraulic mission-age’ blueprint to a leading example of participatory Integrated Water Resource Management, what it calls a ‘human-centred development project’. GAP is now promoted as a socially responsible, integrated water management project (Kibaroğlu 2002). In Spring 2000 in response to many criticisms, GAP was reviewed again in a ‘participatory planning process’, involving groups in such specific fields as rural development plans, social planning, economic planning, environment and infrastructure’ (GAP-RDA 2002: 22).Footnote 9

The project in its new incarnation won a Millennium Award from the International Water Research Association. In this light, donor conditions such as a new Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) and an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) as part of the Project Implementation Plan must have seemed minor. The requested RAP was drawn up by Turkish consultants following World Bank guidelines. The anti-GAP alliance, however, enlisted Ayşe Kudat, a Turkish sociologist who had also worked for the World Bank, to write a critical report on resettlement (Kudat 2000).

An EIA got to be drafted in 2001 (Ilısu Engineering Group 2001), if with a poor baseline (Scheumann et al. 2011). In July 2001, the UK Government’s Export Credit Guarantee Department made the decision whether to provide £160 million backing for the project contingent on ‘public comment’ on the EIA report. Given the ‘securitised’ status of the project, this was not without its problems.Footnote 10 As the EIA did not secure access to credit guarantees for Ilısu, one foreign partner after the other backed out. Skanska withdrew in late 2000, just before the World Commission on Dams issued its influential report with social and environmental guidelines for large dams, which was welcomed by the bilateral donors (Scheumann 2008). ABB had ceded its involvement to French company Alstom. Together with Balfour Beatty, Impreglio withdrew in 2001 after their export credit backers backed out. In 2002, the main financial partner, Swiss UBS Bank, decided to pull out too, after which funding for the project was as good as dead.

4.3 Ilısu revived

The Turkish government, however, was not letting go of its dam like that and found new European partners. After several years of standstill and studies for improvement, the Ilısu Dam project was resurrected in 2005 when a new 14-member consortium including German, Swiss and Austrian companies formed. Alstom of Switzerland (formerly part of ABB) again is involved, along with VA Tech (Austria) and Züblin (Germany), while Cengiz, Celikler and Lider Nurol are Turkish partners.

In response the Keep Hasankeyf Alive (Hasankeyf’i Yaşatma Girişimi) platform was formed. The platform consists of NGOs, mayors from the region and professional chambers (see Eberlein et al. 2010 for its composition). In 2006 the Swiss NGO, Berne Declaration (Erklärung von Bern) scored another coup when they got the famous World Bank sociologist, Michael Cernea, to write a critical assessment of the new Resettlement Action Plan for Ilısu as updated by DSI in July 2006 and the worrying record of earlier GAP resettlement just before the restart of construction works (Cernea 2006). While Morvaridi (2006) has criticised Cernea’s economistic reduction of displaced people to ‘assets’, the World Bank report was gratefully picked up by the anti-dam coalition.

In addition to local action from protest groups such as the Volunteers of Hasankeyf Association and the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive, the international campaign against Ilısu has also been revived, again concentrating on the flooding of Hasankeyf. In the first protests, Friends of the Earth were leading, in the second, a German platform called WEED (now GegenStrömung), which produce a critical weekly Ilısu update, using the case as a focus for opposition to dams in general.

Such campaigns provide an opportunity for local struggles to find global exposure, for local NGOs to link up with international ones. They expose themselves, however, to the risk of capture (hijacking) by the larger interest of the global movement against the global homogenisation of cultural values and neglect of local identities, the sell-out of natural resources by states colluding with global hydro-capitalism.

In the context of the NGO struggle against the Flood Action Plan in Bangladesh in the early 1990s, Kvaloy (1994) wondered whether local protests were stage-managed by internationally funded national NGOs who themselves previously were not very engaged in water issues. This charge, however, cannot be levelled so lightly at the anti-dam coalition in Turkey. While most are not from the region, social and environmental activists find other stakeholders in their camp who may not agree with all NGO issues, most conspicuously to any concessions to Syria and Iraq, but share the (I)NGOs’ dislike of water privatisation. Turkish professionals such as the Chamber of Geology Engineers (TMMOB), who are respected voices in domestic political debate (Bayraktar 2007), have increasingly voiced criticism of the GAP as part of a wider agenda of opposing privatisation, as it places water in the hands of foreigners.Footnote 11 The European Court of Human Rights agreed in July 2006 to hear an application against the dam lodged by archaeologists, journalists and lawyers united in the Hasankeyf Volunteers Association, who feel Hasankeyf must be preserved in its natural state (Smith-Spark 2006; Kart and Özerkan 2006).

The circle of critics has widened since. The official restart of construction works was greeted by 8,000 protesters including leaders of two political parties. The arts also joined, as Turkish Nobel Prize for Literature winner Orhan Pamuk protested and popular singer Tarkan who together with the well-known Turkish environmental group Doğa Dernegi recorded a song in protest of the dam, ‘Uyan’ (wake up). It has become acceptable to criticise Ilısu, and my conversations with Turkish interviewees (May 2010) suggested that the dam may eventually be sacrificed.

However, the Minister for the now-merged department of Culture and Tourism, Atilla Koc, made it clear in 2006 that Hasankeyf would not be saved: ‘Hasankeyf is already gone, it’s been erased from history’, while DSI General Director Eroğlu opined: ‘this dam should have been built 30 years ago’ (quoted by Shoup 2006: 245). The Turkish government took out a US$1.2 bn loan for the dam.Footnote 12 Construction began in August 2006.

A Swiss delegation visited the site to verify that Turkey was complying with international standards before it would guarantee the US$250mn loan. In March 2007, the three countries agreed ‘in principle’ but gave Turkey a 90-day deadline for meeting standards. When this failed to materialise, and after heavy pressure from the NGO coalition, the three donor countries eventually pulled out in 2009 (Eberlein et al. 2010). The Turkish government nevertheless vowed to move ahead with the dam on its own, with domestically generated money (Hürriyet 2010), while European contractors stayed on even without credit guarantee (Guardian, 2009). The NGO coalition, however, refused to budge, targeting Austrian contractor Andritz, who will supply six turbines and generators (Die Presse 2010).

This stand-off belied the palpable rapprochement on both the interstate basin relations and relations with the Kurdish population in Turkey in the past 10 years, and Turkey has meanwhile made significant concessions. While Turkey had initially rejected the norms established by the World Commission on Dams, it started to incorporate them in its dams’ policy (Scheumann 2008). In 2006 the government agreed on conditions and complied with part of the international conditionalities.

Notably, the strong international response to the ‘water war’ argument is surprising as 2001/2002 was a period of thawing Turkey‘s relations with both the Kurds and downstream neighbours. After 1998, the mood among the basin riparians had changed perceptibly towards conciliation or peaceful coexistence. Until 2003, the PKK scaled down violent hostilities which raised hopes of lifting the state of emergency in the region. A new government, still in power today, made openings to recognising Kurdish language, culture and identity. In 2009, the 25th anniversary of anti-GAP violence, Abdullah Öcalan, returned the favour pronouncing to renounce violence and sought a political role for his PKK announcing a road map towards peace with Turkey from his prison cell. The ruling AK-Party has announced its own (heavily criticised) initiatives and claimed that one should separate PKK terrorism from the Kurdish problem. Recent PKK attacks have soured the conciliatory mood.

Relations between Syria and Turkey improved dramatically after the extradition of the PKK leader in 1998, and the conclusion of military and economic agreements was initiated between Turkey and Syria. In 2001, the GAP and the Syrian development project, GOLD, signed a cooperation agreement (Kibaroğlu 2002). In 2002 the two countries shared a Training and Expertise exercise (Protocol of 2002). After the US President started Syria, the Turkish and Syrian leaders started paying mutual visits ion 2004 during which President Bashir Assad was assured that Syria could make further use of the Tigris. A free-trade agreement between the two countries was signed, and the year 2005 saw the establishment of the Euphrates‐Tigris Initiative for Cooperation (ETIC), a non-governmental ‘Track-Two’ initiative for closer cooperation on technical, social and economic development within the river system, headed by ex-GAP-RDA chief Ùnver (Dinar 2009) and included a group of scholars and professionals from Turkey, Syria and Iraq.

While the Ilısu project’s restart on the Tigris in 2006 at first fostered rapprochement between Syria and Iraq on the Euphrates (Mirkasymov 2006), this was deflected by Turkey’s offer to conduct talks with all its water neighbours, if more often on a bilateral rather than trilateral basis. Turkey announced a joint dam project with Syria on the Orontes/Asi. The year 2008 apparently saw a remarkable Iraqi volte‐face on Ilısu on the river Tigris (Yavuz 2008) when Iraq’s Water Minister Rashid reportedly told Turkey’s environment and forestry minister Eroğlu, former head of DSI, that he would like to see the dam built ‘as fast as possible’ (quoted in Yavuz 2008). In Summer 2009, Turkey and Iraq negotiated a one-year agreement guaranteeing a bigger quota, but Turkey seems unwilling to commit to a longer-term river agreement (Wrigley 2009).

For a time, Turkish Foreign Minister Davutoğlu’s ‘zero-problems’ policy stabilised relations with the Arab neighbours (Grigoriadis 2010). But this détente has not prevented problems with activist NGOs, who continue to monitor and criticise the GAP.

5 Discussion and conclusion

In spite of the apparent anarchy and the continuing absence of a basin treaty, a kind of basin regime, in the sense of patterned, predictable state behaviour (Puchala and Hopkins 1983; see also Lopes, this volume), is in place on the Euphrates–Tigris. The public posturing and linkage politics around GAP displays a strongly ritualistic pattern of near-wars followed by near- or placeholder agreements. While these agreements have fallen short of an official treaty, this state of affairs created a stability of expectations which can be seen as an international public good. Indeed, as Kibaroğlu (2002) shows, throughout the GAP’s genesis, the states have worked together rather more than NGO material would have to believe. Technical teams on the Euphrates–Tigris have met on and off despite recurring political threats of military action, a pragmatic acceptance of the faits accomplis on the part of the downstream neighbours.

While Zawahri (2008) has cause to doubt whether one can meaningfully speak of ‘cooperation’ when no actor adjusts their water behaviour for mutual benefit, there is a stability of expectations that justifies the statement that the three countries have maintained an enduring minimal regime at basin scale, with primacy on the part of Turkey. While this regime was built on a degree of brinksmanship, things did get solved by high-level negotiation rather than violence.

Cooperation has been facilitated by geopolitical changes. Since 1998, there has been a move towards more basin cooperation, and downstreamers seem resigned to the next round of dam construction. The Syrian government, having exhausted the leverage the Kurdish card procured them, resigned to Turkish primacy while Iraq is now under direct American tutelage. This geopolitical change also changed the American perspective: used to supporting the strongest actor in river basins to ensure hegemonic stability, Americans are now deeply concerned with the future of the downstreamer and promoting basin cooperation (Zawahri 2006).

The snag is, of course, that while there seems to be a movement from Realist going-it-alone to forms of cooperation, there is hardly question of equal power relations between the partners. Turkey’s neighbours feel that they do not have any real say in the regulatory decisions. They have charged that Turkey is exercising de facto dominance in a context of de jure equality, so that Turkish regulatory decisions such as the occasional arrest of the flow to impound reservoirs have been perceived as unilateral and self-serving. Iraq and, especially, Syria have made repeated, almost ritual threats and used downstream strategies to counter Turkey’s actions.

Cooperation, however, also presents downstreamers with a strategic dilemma. If cooperation becomes more structural, Syria and Iraq lose their leeway for making strong stances as a Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) (see Warner and Zawahri, this issue).

In line with Buzan et al. (1998: 190), we have seen that securitisation can be contagious: securitised non-water issues may spill over into water security issues. Indeed, due to the securitised nature of water relations in the basin, non-water issues between the Euphrates–Tigris riparians also easily became securitised. When the PKK started attacking Turkey’s hydraulic projects, Southeast Anatolia was placed under martial law.

This begs the question whether desecuritisation in one area can also spread to another. A change in domestic leadership has brought Turkish rapprochement towards the domestic Kurdish minority as well as Turkey’s regional neighbours. The current desecuritisation of water at home and abroad in the Euphrates-basin HSC, however, has been halting—while there are currently no open hostilities, relations could quickly sour and bring threats and counterthreats of violence. Turkey remains caught up in a perennial regional ‘insecurity complex’, a permanent sense of unsafety (Aydın 2003). Being situated in a ‘rough neighbourhood’ explains Turkey’s eagerness to exercise domestic and external control (Aydın 2003). While desecuritisation promotes water sharing and integration with domestic and basin riparians, this is widely resisted across the Turkish spectrum.

The Turkish gains in co-opting Syria, accommodating regime change in Iraq and political appeasement with the Kurds would at least have appeared to worsen the prospects for international NGO opposition to Ilısu in 2006. Yet, while basin HSC relations are now placid under the American aegis, the last lap of GAP proved unsafe from (I)NGO attack. Despite the domestic and regional thaw, the campaign against the dams assumed its own dynamics leading to a second retreat from donors and contractors. The first time around, opponents used strong language (‘water wars’), the second time issues of cultural and economic insecurity convinced donors to leave, forcing Turkey to forge ahead on its own pocket.

The analysis suggests that the securitised and desecuritised ‘spheres’ of water politics influence each other and can be structurally linked or delinked. Spurred by PKK attacks and international threats, Turkish political leaders have frequently treated GAP as a national security asset in its struggle with terrorism, deployed army force and denounced dam opponents as terrorists (a strongly ‘securitised’ discourse) and militarised the Southeast region (Warner 2005, 2008; Jacoby 2005, though see Watts 2009). However, the need to generate external funding opened the project to outside influence and scrutiny by actors from a ‘desecuritised’ sphere. This amplified the resonance of NGO countersecuritisation such that it remains a complicating factor in hydropolitical relations. Keck and Sikkink’s (1998) ‘boomerang effect’, involving local NGOs mobilising international actors to pressure their government for reform, thus seems to obtain here: presenting the loss of cultural heritage and threats to Kurdish identity as life-and-death issues continues to cast doubts into the minds of donors and guarantors, causing them to pull out.

The protests and criticisms ignored or dismissed the steady outside-in influence of progressive insight into water development among international water experts seeping through in the Turkish water world. The cordial links of the GAP-RDA leadership with the international epistemic community had facilitated the policy transfer of international emerging Integrated Water Resource Management principles to the GAP, accepting the multiple values and linkages of water and emphasises participatory decision-making (Mukhtarov 2009).

This supports a contextual understanding of how projects are influenced by security speech: while a national (security) crisis can help a project, protest can hurt it when it finds the funders’ ear. The overlaying non-securitised sphere disarmed local securitisation when project funding ran out. Yet, basin detente did not put an end to transnational NGO protest. Long after basin riparians had toned down their security rhetoric, the symbolism of the project welded together a coalition of anti-privatisation actors and human and cultural rights defenders. This almost killed the Ilısu Dam project. Yet, like the proverbial cat, the dam project may prove to have nine lives.

Notes

On the pitfalls of conflating the Euphrates and Tigris into one system, see (Harris and Alatout 2010).

Fox and Sneddon (2007: 239) define environmental securitization as a ‘state-based endeavour to protect access to and control over resources falling within territorial boundaries’.

Not all of these dams are in fact on the Euphrates or Tigris themselves: eight dams are planned under GAP in the valley of the River Munzur in Tunceli and three more on the Greater Zap in Hakkari province.

Turkey (along with two other upstreamers, China and Burundi) decided not to sign the 1997 UN treaty on non-navigable watercourses, claiming the treaty grants downstream states excessive rights.

It is not that the Turks have no sense of history: Turkey has sought to salvage the cultural richness in thousands of important archaeological sites in Anatolia threatened by dam construction; 4–6,500 people in Belkis village (near Gaziantep) and others in Sanliurfa, Gaziantep and Adiyaman Provinces were displaced to make room for Birecik.

By the administration’s own admission, ‘such concerns and concepts as the environment, sustainability, and participation… were either overlooked or totally absent in the original’ (GAP-RDA 2002).

Among the submissions was that of a prominent lawyer, Vefa, whose submission to the ECGD, ‘Legal Review of Ilısu (Hasankeyf) Dam and Evacuated Villages’, was reportedly reprinted in a Turkish law paper and immediately triggered a lawsuit (KHRP et al. 2002).

See e.g. http://www.polarisinstitute.org/turkeys_government_plans_sweeping_water_privatisation_in_run_up_to_world_water_forum_in_istanbul accessed 23 March 2012.

‘Turkije leent miljard voor bouw omstreden dam’, Engineering 360o, 15 August 2007.

Abbreviations

- EIA:

-

Environmental Impact Assessment

- GAP:

-

Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, Southeast Anatolia Project

- INGO:

-

International non-governmental organisation

- RAP:

-

Resettlement Action Plan

References

Allan, J. A. (2007). Rural economic transitions: Groundwater uses in the middle east and its environment consequences. In M. Giordano & K. G. Villholth (Eds.), The agricultural groundwater revolution: Opportunities and threats to development (pp. 63–78). Cambridge, MA.: CAB International.

Aradau, C. (2004). Security and the democratic scene: Desecuritization and emancipation. Journal of International Relations and Development, 7(4), 388–413.

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words: The William James lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Oxford: Clarendon.

Aydin, M. (2003). Securitization of history and geography; understanding of security in Turkey. Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 3(2), 163–184.

Balat, M. (2003). Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) of Turkey and Regional Development Applications. Energy Exploration and Exploitation, 21(5–6), 391–404.

Balzacq, T. (2005). The three faces of securitization: Political agency, audience and context. Journal of International Relations, 111(2), 171–201.

Bayraktar, S.-U. (2007). Turkish municipalities: Reconsidering local democracy beyond administrative autonomy. European Journal of Turkish Studies, URL: http://www.ejts.org/document1103.html Accessed April 2, 2012.

Bilen, O. (2000). Turkey and water issues in the middle east (2nd Ed). Ankara: Turkish Prime Mistry/GAP.

Bosshard, P. (1999). The Ilısu Hydroelectric Project (Turkey): A test case of international policy coherence. Berne Declaration, November 1998.

Brismar, A. (2002). The Atatürk Dam Project in South-East Turkey: Changes in objectives and planning over time’. Natural Resources Forum, 26, 100–112.

Bulloch, J., & Darwish, A. (1993). Water wars. London: Gollancz.

Buzan, B. (1991). People, states and fear: An agenda for international security studies in the post-cold war era (2nd ed.). Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Buzan, B., & Waever, O. (2011). Regions and powers. The strcuture of international security. Cambridge studies on international relations no. 91, Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, B., Waever, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework. Hampstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Cernea, M. M. (2006). Comments on the Resettlement Action Plan for the Ilısu Dam and the HEPP Project. Prepared for the Berne Declaration, Switzerland, and the Ilısu Campaign, Europe.

CNN, (2003). Pentagon: Iraq could flood Tigris for defense. Tactic was used to slow Iranian forces during Iran–Iraq War, 21 March 2003.

Daoudy, M. (2005). Turkey and the region: Testing the links between power asymmetry and hydro-hegemony. Presentation given at first workshop on hydro-hegemony, May 21/22, 2005, King’s College London, UK.

Daoudy, M. (2009). Asymmetric power: Negotiating water in the Euphrates and Tigris. International Negotiation, 14(2), 361–391.

Die Presse, (2010). Ilısu: Andritz liefert ohne Staatsgarantie. 15 June. Online: http://diepresse.com/home/wirtschaft/eastconomist/573957/Ilısu_Andritz-liefert-ohne-Staatsgarantie, Accessed April 2, 2002.

Dinar, S. (2009). Power asymmetry and negotiations in international river basins. International Negotiation, 14(2), 329–360.

Drew, K. (2002). The UK export credit guarantee department, corruption and the case for reform. London: Greenwich University, PSIRU (Public Service International Research Unit).

Eberlein, C., Drillisch, H., Ayboga, E., & Wenidoppler, T. (2010). The Ilısu dam in Turkey and the role of export credit agencies and NGO networks. Water Alternatives, 3(2), 291–312.

Erhan, S. (1997). The social structure in the GAP region and its evolution. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 13(4), 505–522.

El-Fadel, M., El Sayegh, Y., Abou Ibrahim, A., Jamali, D., & El-Fadl, K. K. (2002). The Euphrates–Tigris Basin: A case study in surface water conflict resolution. J. Nat. Res. Life Sci. Educ, 31, 99–110.

Fox, C. A., & Sneddon, C. (2007). Transboundary river basin agreements in the Mekong and Zambezi basins: Enhancing environmental security or securitizing the environment? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 7(3), 237–261.

GAP-RDA (Greater Anatolia Project, Regional Development Administration) (2002). Master Plan. Background of the Southeast Anatolia Project, www.gap.gov.tr/EnglishGgbilgi/gtarihce.html/.

Grigoriadis, I. N. (2010). The Davutoğlu Doctrine and Turkish Foreign Policy. Middle East Studies programme, working paper 8-2010, Bilkent University, Ankara. http://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/ΚΕΙΜΕΝΟ-ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑΣ-8_2010_IoGrigoriadis1.pdf.

Gruen, G. E. (2000). Turkish waters: Source of regional conflict or catalyst for peace? Water, Air, and Soil pollution, 123(1–4), 565–579.

Gruen, G. E. (2004). Turkish water exports: A model for regional co-operation in the development of water resources, 2nd Israeli-Palestinian international conference, 10–14 October 2004, http://www.ipcri.org/watconf/papers/george.pdf.

Hamilton, A. (2003). Resource wars and the politics of abundance and scarcity. Dialogue, 1(3), 27–38.

Harris, L., & Alatout, S. (2010). Negotiating scales, forging states: Comparison of the upper Tigris/Euphrates and Jordan River basins. Political Geography, 29, 148–156.

Hürriyet Daily News, (2010). Loan troubles for Ilısu Dam project nearly over, 31 January.

Ilısu Engineering Group, (2001). Ilısu Dam and HEPP Environmental Impact Assessment Report.

Jacoby, T. (2005). Semi-authoritarian incorporation and autocratic Militarism in Turkey. Development and Change, 36(4), 641–665.

Jongerden, J., Oudshoorn, R., & Laloli, H. (1997). Het verwoeste land, Berichten van de oorlog in Turks Koerdistan. Breda: De Papieren Tijger.

Kart, E. & Özerkan, F. (2006). ‘Ilısu Dam: A gold necklace for Tigris or a rope around Hasankeyf’s neck’, Turkish Daily News, 13 August.

Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

KHRP (Kurdish Human Rights Project, Corner House, Ilısu Dam Campaign), (2002), Downstream Impacts of Turkish Dam Construction on Syria and Iraq, London.

Kibaroğlu, A. (1996). Prospects for co-operation in the Euphrates–Tigris Basin. In P. Howsam & R. Carter (Eds.), Water policy: Allocation and management in practice (pp. 31–39). London: E & FN Spon.

Kibaroğlu, A. (2002). Building bridges between key stakeholders in the irrigation sector: GAP-RDA’s management operation and maintenance model. In O. Unver & R. K. Gupta (Eds.), Water resources management: Crosscutting issues. Ankara: METU Press.

Kibaroğlu, A. (2003). Settling the dispute over the water resources in the Euphrates–Tigris River Basin, Stradigma, July. http://www.stradigma.com/english/july2003/articlesprint_01.html. April 2, 2012.

Kudat, A. (2000). Ilısu Dam`s Resettlement Action Plan (RAP). achieving international best practice, August 7, 2000, Istanbul; unpublished report.

Kvaloy, F. (1994). NGO’s and people’s participation in relation to the Bangladesh flood action plan. Mankodi: Oslo.

Leboeuf, A., & Broughton, E. (2008). Securitization of health and environmental issues: Process and effects. Paris: Institut Français des Relations Internationales.

Litfin, K. (1999). Constructing environmental security and ecological interdependence. Global Governance, 5, 359–377.

Meinecke, M. (1996). Patterns of stylistic changes in Islamic architecture: Local traditions versus migrating artists. New York: University Press.

Mirkasymov, B. (2006). Water resources in the middle east conflict. Journal of Middle Eastern Geopolitics, 2(3), 51–63.

Monbiot, G. (1999, October 14). Close down the export credit guarantee department, The Guardian.

Morvaridi, B. (2006). Rights and development-induced displacement: Is it a case of risk management or social protection? Bradford Centre for International Development Research paper no. 16, University of Bradford.

Mukhtarov, F. G. (2009). The Hegemony of integrated water resources management: A study of policy translation in England, Turkey and Kazakhstan. Doctoral Thesis. Budapest: Central European University.

Munir, M. (2004). Turkey: Corruption notebook. Online; http://www.globalintegrity.org/2004/country.aspx?cc=tr&act=notebook.

Newman, D. (2009). In the name of security: In the name of peace. Environmental schizophrenia facing global environmental change. Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, 4(VIII), 855–864.

Özok-Gündoğan, N. (2005). “Social development” as a governmental Strategy in the Southeastern Anatolia Project. New Perspectives on Turkey, 32, 93–111.

Puchala, D. J., & Hopkins, R. F. (1983). International regimes: Lessons from inductive analysis. International Organization, 36, 427–469.

Scheumann, W. (2008). How global norms for large dams reach decision-makers. A case study from Turkey. In S. Neubert & M. Kipping (Eds.), Water politics and development cooperation local power plays and global governance (pp. 55–81). Berlin/London: Springer.

Scheumann, W., et al. (2011). Environmental impact assessment in Turkish Dam planning. In A. Kramer (Ed.), Turkey’s water policy. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Schulz, M. (1995). Turkey, Syria and Iraq: A hydropolitical security complex. In L. Ohlsson (Ed.), Hydropolitics. Conflicts over water as a development constraint (pp 91–122). London: Zed Books.

Shapland, G. (1997). Rivers of discord: International water disputes in the Middle East. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Shoup, D. (2006). Can archaeology build a dam? Sites and politics in Turkey’s Southeast Anatolia Project. Journal of Mediterranean Archeology, 19(2), 231–258.

Smith-Spark, L. (2006, August 5).Turkey dam project back to haunt Kurds. BBC News.

Starr, J., & Stoll, D. (1988). The politics of scarcity. Water in the middle east. Boulder: Westview Press.

Ullmann, R. H. (1983). Redefining security. International Security, 8(1), 129–153.

Warner, J. (2005). Mending the GAP—hydropolitical security strategies in the Euphrates Tigris basin. In L. Wirkus (Ed.), Water, development and cooperation—comparative perspective: Euphrates–Tigris and Southern Africa; Proceedings of a workshops organised by BICC and ZEF, BICC paper no. 46.

Warner, J. (2008). Contested hydrohegemony: Hydraulic control and security in Turkey. Water Alternatives, 1(2), 271–288.

Warner, J. (2011). Flood planning. The politics of water security. London: IB Tauris.

Warner, J. (2012). Three lenses on water war, peace and hegemonic struggle on the Nile. International Journal of Sustainable Society, 4(1/2), 173–193.

Watts, N. (2009). Re-considering state-society dynamics in Turkey’s Kurdish Southeast. European Journal of Turkish Studies, 10.

Williams, P. (2003). The security politics of enclosing transboundary river water resources. Paper presented at the Conference on Resource politics and security in a global age, University of Sheffield.

Wrigley, P. (2009, October 2). Dam disputes strain Turkey-Iraq ties. Asia Times.

Lopes, P. Duarte (this issue). Governing Iberian Rivers: from bilateral management to common basin governance? International Environmental Agreements.

Yavuz, E. (2008, March 12). Turkey, Iraq, Syria to initiate water talks, Today’s zaman.

Zawahri, N. A. (2006). Stabilising Iraq’s water supply: What the Euphrates and Tigris rivers can learn from the Indus. Third Water Quarterly, 27(6), 1027–1041.

Zawahri, N. A. (2008). Capturing the nature of co-operation, unstable co-operation, and conflict over international rivers: The story of the Indus, Yarmouk, Euphrates, and Tigris Rivers. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 8(3), 286–310.

Zeitoun, M., & Warner, J. (2006). Hydro-hegemony—a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Policy, 8, 435–460.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Warner, J. The struggle over Turkey’s Ilısu Dam: domestic and international security linkages. Int Environ Agreements 12, 231–250 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-012-9178-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-012-9178-x