Abstract

The present research provides evidence of the measurement properties of the Career Education and Development Scale-Junior (CEDS-Junior) and the Career Education and Development Scale-Primary (CEDS-Primary). Study 1 tested a theoretically informed three-factor structure of the CEDS-Junior using a sample of N = 381 junior high school students in grades 7, 8 and 9, and Study 2 tested the CEDS-Primary using a sample of N = 179 primary school students in grades 5 and 6. Three hypothesized factors were recovered from the data: understanding, action and attitude. These novel measures are a resource for exploring and tracking students’ career development learning.

Résumé

La présente recherche fournit des preuves des propriétés de mesure de l'Échelle d'Éducation et de Développement de Carrière-Junior (CEDS-Junior) et de l'Échelle d'Éducation et de Développement de Carrière-Primaire (CEDS-Primaire). L'étude 1 a testé une structure à trois facteurs théoriquement informée de la CEDS-Junior en utilisant un échantillon de N = 381 élèves de collège en 7ème, 8ème et 9ème année, et l'étude 2 a testé la CEDS-Primaire en utilisant un échantillon de N = 179 élèves de l'école primaire en 5ème et 6ème année. Trois facteurs hypothétiques ont été récupérés à partir des données : Compréhension, Action et Attitude. Ces nouvelles mesures sont une ressource pour explorer et suivre l'apprentissage du développement de carrière des élèves.

Zusammenfassung

Die vorliegende Forschung liefert Nachweise für die Messungseigenschaften der Skala zur Berufsbildung und -entwicklung-Junior (CEDS-Junior) und der Skala zur Berufsbildung und -entwicklung-Primar (CEDS-Primar). Studie 1 testete eine theoretisch informierte dreifaktorielle Struktur der CEDS-Junior anhand einer Stichprobe von N = 381 Schülern der Sekundarstufe I in den Klassen 7, 8 und 9, und Studie 2 testete die CEDS-Primar mit einer Stichprobe von N = 179 Grundschülern in den Klassen 5 und 6. Drei hypothetisierte Faktoren wurden aus den Daten extrahiert: Verständnis, Aktion und Einstellung. Diese neuen Maßnahmen sind eine Ressource zur Erforschung und Verfolgung der beruflichen Entwicklung der Schüler.

Resumen

La presente investigación proporciona evidencia de las propiedades de medición de la Escala de Educación y Desarrollo Profesional-Junior (CEDS-Junior) y la Escala de Educación y Desarrollo Profesional-Primaria (CEDS-Primaria). El Estudio 1 probó una estructura de tres factores teóricamente informada de la CEDS-Junior utilizando una muestra de N = 381 estudiantes de secundaria junior en los grados 7, 8 y 9, y el Estudio 2 probó la CEDS-Primaria utilizando una muestra de N = 179 estudiantes de escuela primaria en los grados 5 y 6. Tres factores hipotetizados fueron recuperados de los datos: comprensión, acción y actitud. Estas nuevas medidas son un recurso para explorar y seguir el desarrollo profesional de los estudiantes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Educational jurisdictions and policy agencies are increasingly recognizing the importance and effectiveness of career development learning (CDL) in high schools (Covacevich et al., 2021; Inter-Agency Working Group on Career Guidance; Mann et al., 2020). Watts (2006) defines CDL as being ‘concerned with helping students to acquire knowledge, concepts, skills and attitudes which will equip them to manage their careers, i.e., their lifelong progression in learning and work’ (p. 2). However, it has been known for some time that CDL for younger students is not common practice, and that career education tends to focus on the decision-making of senior high school students preparing for their transition onward from compulsory education to further education, training and employment (McMahon & Watson, 2022; Patton & McMahon, 2021).

Literature reviews by Hartung et al. (2005) and Watson and McMahon (2005) generated five key findings about childhood career development (Porfeli et al., 2008), which were: that children by the age of 4 years have the capacity to learn about careers and can differentiate occupations on the basis of gender; career stereotypes based on gender tend to consolidate over time; career stereotypes impact on career aspirations and negatively influence later subject and course choice; social and cultural stereotypes impact negatively on career aspirations; and that as children grow, they begin to lean towards more realistic aspirations rather than more sensationalized careers. Yet, with the preponderance of theory, research and curricular resources for CDL focussed on senior high school students (Patton & McMahon, 2021), there is a concomitant limitation in the same for younger school students (McMahon & Watson, 2022).

The present research aimed to add evidence about the validity of two new psychometric measures of CDL specifically for students in junior secondary school (i.e. aged 12, 13 and 14 years old; in grades 7, 8 and 9) and in primary school (i.e. aged 10 and 11 years old; in grades 5 and 6). Respectively titled, the Career Education and Development Scale-Junior Secondary (CEDS-Junior) and the Career Education and Development Scale-Primary (CEDS-Primary), these two novel measures of junior and primary students’ career beliefs were designed to be useful resources for teachers, school counsellors, career development practitioners and educational researchers for exploring and tracking students’ CDL. The research findings contribute new conceptualizations and empirical evidence about young students’ career development and in a small way alleviate the dearth of literature about their career development.

Theoretical background

Two ‘classical’ development theories of career that are relevant to children specify stages and psychological processes. Gottfredson (2005) asserted that children move through four stages as they use the two processes of compromise and circumscription in the development of occupational aspirations. The hypothetical stages include orientation to physical size and power (ages 3–5 years); orientation to sex roles (ages 6–8 years); orientation to social valuation (ages 9–13 years); and orientation to an internal, unique self (ages 14 years and above). Stages one to three are relevant to the present research. The process of compromise involves eliminating less compatible but more accessible occupations, while that of circumscription is the process of narrowing the zone of acceptable occupations. At the third stage, around ages 9–13 years, children rank occupations by both prestige and social status.

The lifespan/life space theory of career development (Super, 1990) posited stages from birth to disengagement from the world of work: growth (birth to 14 years), exploration (ages 14–24 years), establishment (ages 25–44 years), maintenance (ages 45–65 years) and disengagement (ages 65 years and older). Super’s model included nine dimensions: curiosity, exploration, information, key figures, interests, locus of control, time perspective, self-concept and planfulness. Super theorized that successful development across these dimensions leads to effective problem solving and decision-making.

Stead and Schultheiss (2003) set out to test Super’s theoretical assumptions by developing a measure that would assess childhood career development across the nine dimensions (Super, 1990). They developed two versions of the Childhood Career Development Scale (CCDS), with one for use in South Africa with 48 items resulting in 8 factors (Stead & Schultheiss, 2003) and one for use in the USA with 52 items and 8 slightly different factors (Schultheiss & Stead, 2004). The scales were administered to students in grades 4–7. Most of the factors proved to be stable in both studies, with no or minimal significant differences in gender and grade for each study. Nazli (2007) explored the career development of primary school children in Turkey by using four dimensions of the CCDS to interview primary school students and found that they were aware of their own self-concepts, that their time perspectives and planning concepts were well developed and that they could link their educational experiences to professions.

Contemporary models of career development

The conceptual framework that underpins the measures CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary is the Career Education and Development Framework (CEDF; McCowan et al., 2023) and the theoretical and empirical framework of career preparedness (Marciniak et al., 2022), which they define as ‘the attitudes, knowledge/competencies and behaviors necessary to deal with the expected and unexpected career transitions and changes’ (p. 19). Figure 1 depicts the CEDF’s conceptual framework. The CEDF consists of eight elements/factors contained within three core components, namely: understanding (self, opportunities and influences); action (goal setting, decision-making, taking action and reflecting/reviewing); and attitude (confidence). This study, involving younger students, focusses on the three-core-component level of the model by Marciniak et al. (2022). The CEDF was used to conceptualize the Career Education and Development Scale-Tertiary (CEDS-Tertiary; McCowan et al., 2024) and the Career Education and Development-Senior (CEDS-Senior; McCowan et al., 2023).

Existing measures tend not to reflect conceptual or curricula frameworks which educators have developed to guide their career education and development programs and practices. Nor do the measures reflect the scope of vocational and career constructs addressed in educational settings. Indeed, a review of measures reveals that they each address some but not all of the eight elements/factors of the CEDF (McCowan et al., 2023). For example, in the Career Development Inventory, Australian, Short Form (CDI-A-SF; Creed & Patton, 2004), self-understanding, knowledge of the world of work, decision-making and some aspects of taking action are addressed, but not understanding influences, goal setting and reviewing/reflecting. Existing scales focus on vocational and career constructs such as career interests (Athanasou, 1988), work values (Work Aspect Preference Scale; Pryor, 1983) and decision difficulties such as the Career Decision Making Self-Efficacy Scale (CDMSES; Betz et al., 1996). Some scales have a multiple focus, such as the Childhood Career Development Scale (Stead & Schultheiss, 2010) and the Career Resources Questionnaire-Adolescent Version (Marciniak et al., 2021), and some scales have a single construct focus such as the Student Career Readiness Index (Dodd et al., 2021). None of these scales are based upon a curriculum framework, and scales used at these earlier levels of schooling need to be not only relatively simple, but also ‘meaningful, comprehensive and economical’ (Marciniak et al., 2021, p. 175).

Purpose of the present research

The purpose of the present research was to investigate the measurement properties of the CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary. The two measures’ construction followed a similar process to the steps recommended by Dodd et al. (2021) and included: allocation of items from existing measures, such as the CDI-A-SF, against the CEDF and adaption of these; checking against career constructs in common use (Swanson & D’Achiardi, 2005; Larson et al., 2013); examining age-appropriate lesson material (McCowan et al., 2022) and cognitive testing through enlisting school career counsellors to conduct focus groups with relevant students, teachers and parents; and undertaking pilot studies. These steps are outlined in more detail in McCowan et al. (2023, 2024) in their work developing the four measures, with the number of items generated for testing purposes being: CEDS-Tertiary and CEDS-Senior, 24 items each; and CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary, 21 items each. Similar career constructs from the CEDF were addressed in all four measures, with the cognitive complexity of the items reduced for younger students.

Study 1 explored the measurement properties of the CEDS-Junior, and study 2 focussed on CEDS-Primary, and undertook the same methodology as the CEDS-Junior. The two studies included other measures to provide evidence of concurrent validity: the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), and the time perspective and key figures sub-scales (i.e. significant others) from the Childhood Career Development Scale (CCDS; Stead & Schultheiss, 2010). We hypothesized that these measures would have moderate correlations with the CEDS, because according to the CEDF, self-esteem, family and support, as well as perspective on the future, should be associated with the core factors of understanding/knowledge, attitudes and actions.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Study 1 recruited students from grades 7, 8 and 9 (aged 12, 13 and 14 years old, respectively) from three schools within a large education jurisdiction in Australia. Of the 462 students who responded, 81 were deemed unsuitable mainly because of missing data, subsequently leaving a sample size of N = 381. Female participation was n = 204 (54%), while male participation was n = 164 (43%), and 13 students (3%) registered as neither male nor female. Participation by school grade was grade 7, n = 95 (25%); grade 8, n = 136 (36%); and grade 9, n = 150 (39%). Participation was spread across three schools: school 1, n =25 (7%); school 2, 12 (4%); and school 3, 344 (89%). The Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA; ACARA, 2020) is a scale which allows for fair and reasonable comparisons among schools with similar students and provides an indication of the socio-educational backgrounds of students. The ISCEA is set at an average value of 1000, which can be used as a benchmark, with lower scores representing relative educational disadvantage compared with the average school, and higher scores representing more advantage than the average. The values for the respective schools are 1057, 1019 and 930, which are close to the average value of 1000.

Measures

Career Education and Development Scale-Junior (CEDS-Junior)

The items for the CEDS-Junior are presented in Table 1.

The measures used for criterion validity were chosen from the list presented by Larson et al. (2013), which aligned instruments with career/vocational constructs. The instruments were selected on the basis of being age appropriate, attempting to measure a similar aspect of the CEDF or relevant career/vocational construct and being relatively short in length.

Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES)

The RSES (Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item scale that measures global self-worth by measuring both positive and negative feelings about the self. The scale is believed to be uni-dimensional. All items are answered using a Likert scale format ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Only the five positive items were used because the scale was presented online and there would be no assistance available if any of the negative items upset the students (e.g. ‘On the whole, I am satisfied with myself’, ‘I feel that I have a number of good qualities’).

Childhood Career Development Scale (CCDS)

The CDDS (Stead & Schultheiss, 2010) is a 74-item scale designed to assess children’s career development across the nine proposed dimensions of Super’s (1990) developmental lifespan/life space theory of career. All items are answered using a Likert scale format ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The items from the two sub-scales, Time Perspective (four items, e.g. ‘It is important to plan now for what I will be when I grow up’) and Key Figures (five items, e.g. ‘I know people who I want to be like’) were included in the study.

Procedure

Ethics approval was granted from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Southern Queensland and from the senior research officer of a major educational jurisdiction in Australia. The CEDS-Junior was set up as an online scale within the secure environment of the USQ data management system. The relevant coordinator for the jurisdiction involved invited schools to participate and provided training and access for the relevant person in each of the schools which agreed to participate. The online version was accessible for 1 month and students who had appropriate parent permission were able to access the scale at any time in that period. The measures took approximately 8 min for students to complete online.

Plan for analysis

SPSS v.28 and AMOS v.28 were used for data analysis. Given that the CEDS is based on a theoretical framework, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimator to test the measurement models. Model fit was appraised using the χ2 test; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.10; SRMR standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) < 0.08; and comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90 (Mvududu & Sink, 2013). Model testing was followed by analysis of mean differences across genders and grade levels, and correlational analysis of the CEDS’ mean scores with the measures of self-esteem, time perspective and significant others.

Results

The initial CEDS-Junior model comprised the original seven items per factor. The model had an unacceptable fit: χ2(186, N = 381) = 871.923, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.860, SRMR = 0.065, RMSEA = 0.099, CI 90% (0.092, 0.105). The model was modified by removing from each factor those items with the weakest squared multiple correlations (i.e. Attitude 1, r2 = 0.45; Action 5, r2 = 0.56; and Understanding 4, r2 = 0.31). The revised model with six items per factor had a better fit to the data but remained unacceptable: χ2(132, N = 381) = 570.138, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.892, SRMR = 0.059, RMSEA = 0.093, CI 90% (0.086, 0.101). Inspection of modification indices revealed high coefficients for Understandings 6 and 7, Actions 2 and 7, Actions 6 and 7, Attitudes 2 and 3 and Attitudes 6 and 7. Covarying those items produced an acceptable fit to the data: χ2(127, N = 381) = 374.198, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.939, SRMR = 0.048, RMSEA = 0.072, CI 90% (0.063, 0.080). We made no further changes and retained the six-item model.

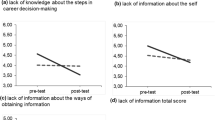

Mean differences

Differences between the mean scores for female and male participants and students in grades 7, 8 and 9 are presented in Table 2. The differences are minimal; however, multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) with gender (2) and grade (3) as the independent variables revealed the presence of significant differences among the dependent variables for grade, using Pillai’s trace V = 0.07, F(12, 716) = 2.20, p = 0.01, but not for gender. There was no overall interaction effect. Follow-up analysis of variance (ANOVA) tested for between-subjects’ effects and found significant differences across grades for: Understanding, F(2, 362) = 6.31, p = 0.002, partial eta2 = 0.034; Action, F(2, 362) = 3.28, p = 0.039, partial eta2 = 0.018; and Attitude, F(2, 362) = 3.22, p = 0.041, partial eta2 = 0.017; but not for Figures, Time, and Esteem. Furthermore, there was a significant difference across gender for Esteem, F(1, 362) = 8.46, p = 0.004, partial eta2 = 0.023. Bonferroni post hoc tests revealed that grade 7 students had relatively higher mean scores for Understanding, Action, and Attitude than the grade 8 and 9 students.

Correlations

Table 3 displays correlations among the measures. The Key Figures and Time Perspective sub-scales of the CCDS (Stead and Schultheiss 2010) correlated moderately to strongly with each of the three factors of the revised CEDS-Junior, with the coefficients ranging from r = 0.43 to 0.49 for Figures and r = 0.49 to 0.56 for Time. The shortened version of the RSES correlated strongly with each of the three factors of the revised CEDS-Junior, with the coefficients ranging from 0.48 to 0.74. These strong correlations with the three measures provide additional evidence of validity of the CEDS-Junior.

Summary

Study 1 provided the first evidence of validity of the CEDS-Junior regarding its factor structure and convergence with measures of career-related constructs. There were no differences between the boys’ and girls’ scores on the CEDS’s sub-scales; however, the younger students in grade 7 had higher scores for the three sub-scales.

Study 2

The purpose of study 2 was to test a possible three-facture structure for CEDS-Primary through subjecting the data to CFA and by using other measures for validity evidence, the same as for study 1.

Participants

Study 2 involved students from grades 5 and 6 in three schools within a large education jurisdiction in Australia. Of the 212 students who responded, 33 were deemed unsuitable mainly because of missing data, subsequently leaving a sample size of N = 179. Female participation was n = 84 (47%), while male participation was n = 84 (47%), and 11 students (6%) registered as neither male nor female. Participation by school grade was: grade 5, n = 92 (51%) and grade 6, n = 84 (49%). Participation was spread across three schools: school 1, n =37 (21%); school 2, n = 39 (22%); and school 3, n =102 (57%). The ISCEA values for the respective schools are the same as listed in study 1.

Measures

As in study 1, the five positively worded items of the RSES (Rosenberg, 1965) and sub-scales of four items and five items of the CCDS (Stead & Schultheiss, 2010) Time Perspective and Key Figures, respectively, were used as for evidence of concurrent validity.

Career Education and Development Scale-Primary (CEDS-Primary)

CEDS-Primary was used for this study. There were 7 items representing each of the 3 components of Understanding, Action and Attitude (21 items in total). The process for developing this scale was the same as in study 1. The revised version is presented in Table 4 in the Results section together with the factor loadings for each item.

Procedure

Ethics approval and procedures mirrored the process of study 1, as CEDS-Primary was made available for students in grades 5 and 6 at the same time as CEDS-Junior was made available for students in grades 7, 8 and 9.

Results

We tested the three-factor model with the original seven items per factor and its fit was unacceptable, χ2(186, N = 179) = 408.047, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.866, SRMR = 0.064, RMSEA = 0.082, CI 90% (0.071, 0.093). Like study 1, we removed the weakest item from each factor with the lowest squatted multiple correlations (i.e. Attitude 6, r2 = 0.30; Action 3, r2 = 0.23; Understanding 4, r2 = 0.24) and then tested a three-factor model with six items per factor. The amendments produced a better fitting model: χ2(186, N = 179) = 271.280, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.903, SRMR = 0.056, RMSEA = 0.077, CI 90% (0.064, 0.090). Again, similar to the process used for study 1, we inspected modification indices for relatively high coefficients and covaried Understandings 2 and 3 and Attitudes 4 and 5. The subsequent model revealed an improved fit to the data, χ2(130, N = 179) = 233.636, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.928, SRMR = 0.055, RMSEA = 0.067, CI 90% (0.053, 0.081). No further modifications were made.

Mean differences

Differences between the mean scores for female and male participants in grades 5 and 6 are presented in Table 5. The differences are minimal; however, multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) with gender (2) and grade (2) as the independent variables revealed the presence of significant differences among the dependent variables for grade, using Pillai’s trace V = 0.10, F(6, 159) = 2.98, p = 0.009, partial eta2 = 0.10, and for gender, V = 0.13, F(6, 159) = 3.80, p = 0.001, partial eta2 = 0.125. There was no interaction effects of gender × grade. Follow-up ANOVA tests of between-subjects effects for grade found significant differences for: Attitude, F(1, 164) = 12.41, p < 0.001, partial eta2 = 0.07; and, Esteem, F(1, 164) = 10.78, p = 0.001, partial eta2 = 0.06. Within gender, there were significant differences for: Attitude, F(1, 164) = 4.62, p = 0.03, partial eta2 = 0.03; Figures, F(1, 164) = 10.67, p = 0.001, partial eta2 = 0.06; and Esteem F(1, 164) = 4.74, p = 0.03, partial eta2 = 0.03.

Correlations

The shortened version of the RSES (Rosenberg, 1965) correlated strongly with each of the three components of the CEDS-Primary, with the coefficients being r = 0.56 for Understanding, r = 0.60 for Action and r = 0.67 for Attitudes. Similarly, the Key Figures (r = 0.40, 0.51 and 0.47) and Time Perspective (r = 0.56, 0.60 and 0.67) sub-scales of the CCDS (Stead & Schultheiss, 2009) scale also correlated very strongly with each of the components of the revised CEDS-Primary, as presented in Table 6. These strong correlations with the three measures provided additional evidence of validity of the CEDS-Primary.

Summary

Study 2 provided the first evidence of validity of the CEDS-Primary regarding its factor structure and convergence with measures of career-related constructs. Unlike the CEDS-Junior, there is an evident difference between the boys’ and girls’ scores on the CEDS’s Attitudes sub-scale, although the effect size is small. There is also a difference for Attitude between the two grades.

Discussion

The two studies reported here provide the first evidence of validity and reliability of the CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary, which were specifically developed for use with junior secondary school and primary school students, respectively. For CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary, their three-factor structure reflects the three core components of the CEDF (McCowan et al., 2023) and three factors posited in the empirically derived model of Marciniak (2022), namely, Understanding, Action, and Attitude. Affirmation of the three-factor model in all four versions of the CEDS, namely the CEDS-Primary and CEDS-Junior in the present research, and the CEDS-Senior and CEDS-Tertiary in McCowan et al. (2023, 2024), provides evidence of the theoretical value of the CEDF that underpins the four CEDS frameworks. Researchers and practitioners can now trace the development of the same career constructs starting at a relatively young age and ranging across a wide age span. Additional evidence of validity is present in the CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary factors’ correlations with the measures of self-esteem, future perspective and the influence of significant others.

That grade 7 junior high school students had marginally higher mean scores on CEDS-Junior’s Understanding, Action, and Attitude than the grade 8 and 9 students’ scores presents an interesting theoretical conundrum, as these students are, theoretically, in the same career development stage of exploration. An explanation cannot be found in the students’ self-esteem, sense of the future and attitudes towards significant others, because these measures were not significantly different across the grades. Nonetheless, grade 7’s marginally higher scores should be treated with caution because the effect size partial eta2 for each was small. Similarly, girls presented marginally lower mean scores for self-esteem, but the effect size was also small. The pattern of difference among the mean scores for the primary school students was somewhat different. As with junior high, the girls in primary school had lower self-esteem than the boys, albeit a small effect size. We note that this small difference in self-esteem between male and female participants is commonly noted in research literature as a consistently evident phenomenon (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Casale, 2020).

The findings from these two studies reinforce the findings by Marciniak et al. (2022), in which their extensive research on career maturity, career readiness, career adaptability and career preparedness revealed three groupings of constructs like the three components of the CEDF. The research by Stead and Schultheiss (2003) and Schultheiss and Stead (2004) with primary school students found that their eight factors proved to be stable, with no or minimal differences in gender and grade, much like the findings in studies 1 and 2 here. Nazli (2007) also found that primary school students were aware of their own self-concepts, their career planning concepts were well developed and they could link their current experiences to future professions. Similarly, our studies found that younger students were able to identify with the three core components of the CEDF.

CEDS-Junior and CEDS-Primary provide career practitioners and researchers with two relatively short psychometric measures to use with younger students. Their three sub-scales of Understanding, Action, and Attitudes are related to the comprehensive set of eight sub-scales measured in later years using the CEDS-Senior. Thus, these two measures for younger students can become baselines for subsequent assessments using CEDS-Senior in later years of schooling.

Practical implications

Teachers and career practitioners now have access to two self-assessment measures based on the already validated CEDF, which can be used with confidence by their students. The CEDS-Primary can be used with students aged 10–12 years and CEDS-Junior with students aged 12–15 years. Because the measures are developmental in nature and use the same theoretical framework, teachers can scaffold similar activities and processes with students in the early years to those in subsequent years. Their work will then dovetail into and around the use of the CEDS-Senior, which has been validated in a previous study (McCowan et al., 2023) and is suitable for students aged 15–18 years.

Given the importance of formal career-related learning at these early stages of student development to broaden horizons, challenge stereotypes, link learning to the world of work and promote a sense of self (Porfeli et al., 2008; DMH Associates, 2021), the CEDS-Primary and CEDS-Junior will facilitate the development and implementation of activities and programs to address these issues through promoting and supporting thse awareness and importance of CED in primary and junior secondary schools, celebrating areas of competence, identifying and focussing on developing activities in areas that need strengthening (e.g. career planning) and providing information to guide lesson planning and program development. The economical and holistic nature of the scales (Marciniak et al., 2021) mean that they can be implemented for different purposes; for example, with individual students, as pre- and post-measures of an intervention, embedded in the curriculum to progress students’ career thinking and evaluate strengths and weaknesses of a program, and as a way of determining the general level of career development of students in an institution or educational system. Their outcomes could be used as a basis for learning and/or discussion with parents and teachers as well as to facilitate policy development and the development and allocation of valuable career resources where they are most needed. Nonetheless, we cannot assume at this stage of the CEDS’ development that it has measurement stability over time (e.g. test–retest reliability).

Limitations and future research

These two studies were conducted in a large, mainly provincial, educational jurisdiction in Australia and the sample used for the CEDS-Primary was relatively small. Although simulation studies suggest small samples may yield outcomes in factor analytic studies (de Winter, et al., 2009), further research needs to be undertaken to include larger numbers of students and students from a more diverse range of geographical locations and ethnic backgrounds. No socio-economic data other than the ISCEA was collected for each school. Future research could focus on target populations in different types of institutions in varying locations and provide evidence of the impact of SES and/or ethnicity on student responses (Choi et al., 2012). Possible links could be explored between the CEDS and academic performance and dispositional traits that are associated with career decidedness and exploration. It would also be important to do comparative studies between students who have been involved in an explicit career education and development program and those who have not.

The differences in girls’ mean scores for Attitude and Esteem girls across grades 5 and 6 warrants further investigation (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Casale, 2020). Is this difference associated with the transition from the fantasy sub-stage to dealing with the capacities and crystallization sub-stages (Super, 1990) or the transition from the second to third stages in Gottfredson’s (2005) theory, in which she postulates that students can now array occupations two-dimensionally, by prestige and sex type, whereas before this, they aspired to occupations along one dimension, low or high alike (Gottfredson, 2005, p. 79)? Are the differences associated with pre-pubescence for girls or increased maturity around this age range? Targeted research is required to address the validity of these findings.

The data were collected online voluntarily, and several students chose not to complete the survey or to adopt a response-biased approach. CEDS-Primary and CEDS-Junior are based on self-reporting and thus susceptible to self-reporting bias (e.g. where participants over- or under-estimate their career understandings, behaviours and attitudes) (Donaldson & Grant-Vallon, 2002). Dyadic or 360-degree data collection methodology, which compares the self-reports with other relevant data and personal observations, would address this concern. Future research could also investigate whether the CEDS’ measurement properties are invariant across time and successive administrations.

Conclusions

The present study brings to completion a program of research into the CEDF which developed separate CEDS measures for students in tertiary colleges and senior high school (i.e. grades 10, 11 and 12; McCowan et al., 2023, 2024) and now, junior high school grades 7, 8 and 9, and primary school grades 5 and 6. The research program has thus developed resources spanning grades 5–12 and college years. These measures provide researchers and educational practitioners with a valuable resource for longitudinally tracking students’ CDL as they progress through their schooling.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2009). Amos (version 18.0). Amos Development Corporation.

Athanasou, J. A. (1988). The career interest test. Hobsons Press.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2020). Guide to understanding the index of community socio-education advantage. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority.

Betz, N. E., Klein, K. L., & Taylor, K. M. (1996). Evaluation of a short form of the career decision-making self-efficacy scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/106907279600400103

Bleidorn, W., Arsian, R. C., Denissen, J. J., Rentforw, P. J., Gebauer, J. E., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross cultural window. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 396–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000078

Casale, S. (2020). Gender differences in self-esteem and self-confidence. In B. J. Carducci, C. S. Nave, A. Annamaria Di Fabio, D. H. Saklofske, & C. Stough (Eds.), The Wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 185–189). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119547174.ch208

Choi, B. Y., Park, H., Yang, E., Lee, S. K., Lee, Y., & Lee, S. M. (2012). Understanding career decision-making self-efficacy: a meta-analytic approach. Journal of Career Development, 39, 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845311398042

Covacevich, C., et al. (2021). Thinking about the future: career readiness insights from national longitudinal surveys and from practice, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 248, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/02a419de-en

Creed, P. A., & Patton, W. (2004). The development and validation of a short form of the Australian version of the career development inventory. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 14(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1037291100002442

Department of Schools and Communities New South Wales (DSC NSW). (2014). The case for career-related learning in primary schools. Public Schools NSW.

de Winter, J. C., Dodou, D. I., & Wieringa, P. A. (2009). Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(2), 147–81.

Dodd, V., Hanson, J., & Hooley, T. (2021). Increasing students’ career readiness through career guidance: Measuring the impact with a validated measure. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 49(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1937515

Donaldson, S. I., & Grant-Vallone, E. J. (2002). Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 245–260.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Applying Gottfredson theory of circumscription and compromise in career guidance and counseling. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 71–100). Wiley.

Hartung, P. J., Porfeli, E. J., & Vondracek, F. W. (2005). Child vocational development: a review and reconsideration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 385–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.006

Inter-Agency Working Group on Career Guidance. (2021). Investing in career guidance: Revised edition 2021. https://www.skillsforemployment.org/skpEng/knowledge-product-detail/1207

Larson, L. M., Bonitz, V. S., & Pesch, K. M. (2013). Assessing key vocational constructs. Handbook of Vocational Psychology: Theory Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203143209

Mann, A., Denis, V., Schleicher, A., Ekhtiari, H., Forsyth, T., Liu, E., & Chambers, N. (2020). Dream Jobs? Teenagers’ career aspirations and the future of work. Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

Marciniak, J., Hirschi, A., Johnston, C., & Haenggli, M. (2021). Measuring career preparedness among adolescents: development and validation of the Career Resources Questionnaire–Adolescent Version. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720943838

Marciniak, J., Johnston, C. S., Steiner, R. S., & Hirschi, A. (2022). Career preparedness among adolescents: a review of key components and directions for future research. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845320943951

McCowan, C., McKenzie, M., & Shah, M. (2022). Introducing career education and development: A guide for personnel in education institutions in both developed and developing countries (2nd ed.). In House Publishing.

McCowan, C., McIlveen, P., McLennan, B., Perera, H. N., & Ciccarone, L. (2023). A Career Education and Development Framework and measure for senior secondary school students. Australian Journal of Career Development, 32(2), 122–134.https://doi.org/10.1177/10384162231164572

McCowan, C., McIlveen, P., McLennan, B., Ho, P., Lê, Đ. A. K., & Tran, N. D. (2024). Career education and development scale for secondary and tertiary students in Vietnam. The Career Development Quarterly, 72(2), 158-171. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12347

McMahon, M., & Carroll, J. (1999). Constructing a framework for a K-12 career education program. Australian Journal of Career Development, 8(2), 43–46.

McMahon, M., & Watson, M. (2022). Career development learning in childhood: a critical analysis. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(3), 345–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2022.2062701

Nazli, S. (2007). Career development in primary school children. Career Development International, 12, 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430710773763

Patton, W., & McMahon, M. (2021). Career development and systems theory: connecting theory and practice (4th ed.). Brill.

Porfeli, E. J., Hartung, P. J., & Vondracek, F. W. (2008). Children’s’ vocational development: a research rationale. The Career Development Quarterly, 57, 25–37.

Pryor, R. G. (1983). Work aspect preference scale manual. Australian Council for Educational Research.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Journal of Acceptance and Commitment Therapies. Measures Package, 61, 52.

Schultheiss, D. E. P., & Stead, G. B. (2004). Childhood career development scale: scale construction and psychometric properties. Journal of Career Assessment, 12, 113–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072703257751

Stead, G. B., & Schultheiss, D. E. P. (2003). Construction and psychometric properties of the Childhood Career Development Scale. South African Journal of Psychology, 33, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630303300405

Stead, G. B., & Schultheiss, D. E. P. (2010). Validity of childhood career development scale scores in South Africa. Journal of Educational and Vocational Guidance, 10(2), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-010-9175-y

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development: applying contemporary theories to practice (2d ed., pp. 197–261). Jossey-Bass.

Swanson, J. L., & D’Achiardi, C. (2005). Beyond interests, needs/values, and abilities: assessing other important career constructs over the life span. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling. Putting theory and research to work (pp. 353–381). Wiley.

Watson, M., & McMahon, M. (2005). Children’s career development: a research review from a learning perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.011

Watts, A. G. (2006). Career development learning and employability. The Higher Education Academy.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors did not receive funding from any organization to conduct this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.M., P.M. and B.M.; data analysis: C.M., P.M. and B.M.; investigation: all authors; methodology: C.M., P.M. and B.M.; project administration: C.M., P.M. and B.M.; resources: C.M. and L.C.; supervision: P.M. and B.M.; writing—original draft: C.M.; and writing—review and editing: P.M. and B.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Southern Queensland. One of the authors is a member of the advisory board of the International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. The authors declare that there are no competing interests or conflicts of interest pertaining to the content of the article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McCowan, C., McIlveen, P., McLennan, B. et al. Career education and development scales for primary school and junior secondary school students. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-024-09678-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-024-09678-3