Abstract

In recent years, to better face university paths, the first approaches to the labor market, and then the actual university-to-work transition, university students are asked to have broader skills, such as the ability to network, to be involved in career-related issues, and to explore the characteristics of occupations as much as personal ones. This study aims to verify the psychometric properties of the Italian translation of the Career Resources Questionnaire–Adolescent version (CRQ-A; Marciniak et al., 2020) among two samples of undergraduate students (N1 = 270; N2 = 184). Differently from the original version, exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis suggested a 10-factor structure. Reliability and validity were confirmed. The results indicate that the Italian version of CRQ-A is a valid multidimensional instrument for exploring undergraduate students’ career preparedness, consequently favoring universities in their role of preparing students for the decoding of the labor market and themselves as future workers. Résumé. Ces dernières années, pour mieux affronter les parcours universitaires, les premières approches du marché du travail, puis la transition université-travail proprement dite, on demande aux étudiants universitaires d'avoir des compétences plus larges, telles que la capacité à travailler en réseau, à s'impliquer dans les questions liées à la carrière et à explorer les caractéristiques des professions autant que les caractéristiques personnelles. Cette étude vise à vérifier les propriétés psychométriques de la traduction italienne du Career Resources Questionnaire-Adolescent version (CRQ-A ; Marciniak et al., 2020) auprès de deux échantillons d'étudiants de premier cycle (N1 = 270 ; N2 = 184). Contrairement à la version originale, l'analyse factorielle exploratoire et l'analyse factorielle confirmatoire ont suggéré une structure à 10 facteurs. La fiabilité et la validité ont été confirmées. Les résultats indiquent que la version italienne du CRQ-A est un instrument multidimensionnel valable pour explorer la préparation à la carrière des étudiants de premier cycle, ce qui favorise les universités dans leur rôle de préparation des étudiants au décodage du marché du travail et d'eux-mêmes en tant que futurs travailleurs. Zusammenfassung. In den letzten Jahren wird von Universitätsstudenten verlangt, dass sie über umfassendere Fähigkeiten verfügen, wie z. B. die Fähigkeit, sich zu vernetzen, sich mit berufsbezogenen Fragen zu befassen und die Merkmale von Berufen sowie persönliche Eigenschaften zu erkunden, um den Übergang von der Universität ins Berufsleben besser bewältigen zu können. Diese Studie zielt darauf ab, die psychometrischen Eigenschaften der italienischen Übersetzung des Career Resources Questionnaire-Adolescent Version (CRQ-A; Marciniak et al., 2020) unter zwei Stichproben von Studenten (N1 = 270; N2 = 184) zu überprüfen. Anders als bei der Originalversion ergaben die explorative Faktorenanalyse und die konfirmatorische Faktorenanalyse eine 10-Faktoren-Struktur. Reliabilität und Validität wurden bestätigt. Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass die italienische Version des CRQ-A ein valides multidimensionales Instrument zur Erforschung der Berufsvorbereitung von Studenten ist und somit die Universitäten in ihrer Rolle unterstützt, Studenten auf die Entschlüsselung des Arbeitsmarktes und auf sich selbst als zukünftige Arbeitnehmer vorzubereiten. Resumen. En los últimos años, para afrontar mejor las trayectorias universitarias, los primeros acercamientos al mercado laboral y, posteriormente, la propia transición universidad-trabajo, se pide a los estudiantes universitarios que tengan habilidades más amplias, como la capacidad de establecer redes de contactos, de implicarse en cuestiones relacionadas con la carrera profesional y de explorar las características de las ocupaciones tanto como las personales. Este estudio tiene como objetivo verificar las propiedades psicométricas de la traducción italiana del Cuestionario de Recursos de Carrera-Versión para Adolescentes (CRQ-A; Marciniak et al., 2020) entre dos muestras de estudiantes universitarios (N1 = 270; N2 = 184). A diferencia de la versión original, el análisis factorial exploratorio y el análisis factorial confirmatorio sugirieron una estructura de 10 factores. Se confirmaron la fiabilidad y la validez. Los resultados indican que la versión italiana del CRQ-A es un instrumento multidimensional válido para explorar la preparación profesional de los estudiantes universitarios, favoreciendo en consecuencia a las universidades en su papel de preparar a los estudiantes para la decodificación del mercado laboral y a ellos mismos como futuros trabajadores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nowadays, young people face an uncertain economic situation and an increasingly competitive job market (Clements & Kamau, 2018). Therefore, school-to-university and university-to-work transitions are more difficult than they were in the past. Processes of social, economic, and technological change have reshaped daily life and work; mobility has increased, career paths are more unstable (Santisi et al., 2018), and the recent pandemic has created—or cleared through customs—new forms of work (Spurk & Straub, 2020). This has changed and broadened the professional and social skills required of young workers.

Several researchers have discussed the notion of “new careers,” characterized by flexibility, autonomy (Hirschi et al., 2015), instability, and the ability to change work roles and move beyond the boundaries of individual occupations and work settings (Santisi et al., 2018). Due to changes in the world of work, individuals are required to exercise more control to direct their career development, and this affects all ages (Marciniak et al., 2020). In short, individuals must exhibit proactive career behaviors (Clements & Kamau, 2018; Hirschi et al., 2018; Marciniak et al., 2020), such as career planning, career exploration, and career networking (Praskova et al., 2015; Strauss et al., 2012). Young people, specifically, are required to start practicing these behaviors already in school to be ready for subsequent transitions (Akkermans et al., 2018). Students are required to explore possible career paths; investigate their vocations, interests, and professional values; engage in career-related experiences; cultivate useful social contacts; create career plans; and finally develop the career resources that will be needed to accomplish all these goals (Praskova et al., 2015; Akkermans et al., 2018; Marciniak et al., 2020).

Recognizing interests, skills, values, and motivations and linking them to appropriate career roles is a critical step in youth development (Praskova et al., 2015). This process will lead to the construction of a career identity, which is particularly important, as it will guide individuals’ career choices and experiences (Meijers, 1998). The consonance between career identity and career undertaken is positively related to well-being, academic and work performance, and job and life satisfaction (Akkermans et al., 2018; Hirschi et al., 2018). Stabilizing a career identity and choosing a career path, however, are challenging tasks. The options are countless, and choosing is not always easy. Moreover, many students do not feel prepared enough to make career choices, because they feel they do not have enough information (Kleine et al., 2021). Other reasons contribute to indecision. For example, the situations of economic uncertainty associated with some career paths may mean that young people’s career choices are not always aligned with their desires and interests, but rather with other relevant values or issues, such as job security and remuneration.

To facilitate the choice process, schools usually involve young people in activities aimed at stimulating them to self- and career exploration (Kleine et al., 2021). These exploration activities help students focus on their career goals (Lent & Brown, 2013). Gathering information about career opportunities and reflecting on how one’s skills and inclinations might fit into a profession increase students’ awareness of careers and themselves (Akkermans et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019). Clarifying expectations, in turn, facilitates achievement (Akkermans & Tims, 2017). Indeed, career exploration is associated with self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and confidence (Praskova et al., 2015; Santisi et al., 2018).

Another resource is career planning, which is equally critical to career identity development (Hirschi et al., 2015; Stringer et al., 2011) and interconnected to career preparedness. During the career preparation process, the individual reflects on and makes sense of their experiences, becomes aware of what they like and dislike, identifies a career path, and ultimately creates a coherent career identity (Savickas, 2002). Career planning and exploration can be instances of adaptation because individuals implement these behaviors whenever they face job changes, whether they are changes in roles, tasks, or actual work (Hirschi et al., 2015; Savickas et al., 2018). In short, they can be perceived as modern adaptability resources (Hirschi et al., 2015).

As mentioned above, adaptability is a key competence nowadays, as it is necessary to respond to the constant and unpredictable changes in today’s society and labor market. It can be assessed by determining whether and how much individuals have participated in vocational planning, exploration, and choice activities (Savickas et al., 2018), and can be predicted by the presence or absence of some variables. For example, it has been found that high self-efficacy beliefs promote the development of adaptability, as well as clarity of objectives and a supportive context (Hirschi, 2009). The latter is particularly influential on young people. Social support from family, school, and peers can facilitate, if present, or hinder, when absent, career exploration, planning, and, ultimately, satisfaction with one’s career choice (Hirschi & Freund, 2014). All of these variables are crucial predictors of career adaptability among high school students and are positively associated with adaptive personalities, higher levels of career decision-making ability, and adaptive career identity development (Hirschi, 2009). Not only exploration, planning, and choice, therefore, but also confidence, clarity, involvement, and social support are fundamental characteristics for positive career development (Hirschi & Herrmann, 2013).

However, as is immediately evident, many measures would be needed to assess all facets of career preparedness, which is not always possible (Marciniak et al., 2020).

Hirschi and colleagues (2018), after a careful review of the literature, developed a questionnaire that could concisely contain all the career resources that are relevant in career preparedness research and predictive for successful career development. Based on the Career Resources Model (Hirschi, 2012), the Career Resources Questionnaire (CRQ; Hirschi et al., 2018) was validated among employees and university students. A later version was then validated by Marciniak and colleagues (2020) and adapted for adolescents (CRQ-A).

According to the Career Resources Model (Hirschi, 2012), career resources can be interpreted as predictors of career success, since they are personal characteristics that could help (or, conversely, limit) individuals in the pursuit of their career goals. According to Hirschi, career resources can be grouped into four categories: (1) knowledge and skills resources (occupational expertise, labor market knowledge, and soft skills); (2) environmental resources (external support from different sources); (3) motivational resources (career involvement, career confidence, and career clarity); and (4) career management behaviors (networking, career information seeking, and continuous work-related learning). The first category refers to human capital, i.e., the set of skills, attitudes, and knowledge essential to respond well to job role expectations. The second category refers to social capital, i.e., the set of resources provided by the context surrounding individuals, both in terms of the network and the environment supporting career development. The third category concerns the psychological resources that the individual has and can use to better face professional challenges. Finally, the last category refers to career identity, i.e., the set of perceptions and awareness related to oneself as a worker and the expectations connected to that role. According to this model, the possession of these characteristics can facilitate the achievement of career success, both objective (measurable through career progression) and subjective (measurable through the perception of job satisfaction and employability; Hirschi et al., 2018). This theoretical framework has proven useful in comprehensively and economically capturing the most important aspects of career preparedness among both workers (Hirschi et al., 2018) and adolescents (Marciniak et al., 2020). The choice of the CRQ dimensions depends on a careful review of the literature on the subject, and on the authors' choice to focus on malleable characteristics, on which one could possibly intervene, rather than on personality traits or other relatively fixed characteristics (e.g., cognitive skills, general self-efficacy, optimism, proactive personality, extroversion, etc.). Possessing specific occupational and labor market knowledge and skills, as well as potentially broadly useful soft skills to adequately position oneself in the world of work, seem to be constitutive dimensions of employability (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005); specifically, they constitute the human capital aspect of it (Hirschi et al., 2018). The aspects of engagement, confidence, and clarity constitute the motivational aspects of career resources, as they relate, respectively, to the sense of attachment and belonging to the job role, the belief that one is capable of successfully developing the chosen career path, and the determination to pursue given career goals (Hirschi et al., 2018). Each of these components appears to be essential for job satisfaction (Ng et al., 2005), adaptability (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012), and employability (Fugate et al., 2004).

Regarding self- and career exploration, they concern the collection of information regarding careers and the degree of self-knowledge as a worker. They are part of the set of competencies called career self-management competencies (Akkermans et al., 2013), along with the ability to build social relationships, maintain them, and eventually exploit them for career development purposes (Akkermans et al., 2013). These three dimensions compose career management behaviors (Hirschi et al., 2018).

Given the diverse evidence of the overlap of the dimensions mentioned so far with several other constructs in the literature, to test convergent validity in Study 2 we chose to correlate the CRQ dimensions with constructs such as decision-making self-efficacy (Lent et al., 2016; Lo Presti et al., 2013) and career role values (Amantea et al., 1986) and with other previously validated scales for networking skills (Ferris et al., 2005) and assessment of perceived social support (Malecki & Elliots, 1999).

As for the differences between the original CRQ and the adolescent version, they mainly concern the purpose for which the two questionnaires were created. The main purpose of the CRQ was to assess the possible antecedent variables of career success; the purpose of the CRQ-A, however, is to assess the variables that might contribute to the preparedness of young people to have a successful career. In the first, the focus is on what the foundation for career success can be, both objective and subjective. In the second, the focus is on the individual and contextual resources that can put young people in the best conditions to face their career path. Consequently, the adolescent version by Marciniak and colleagues (2020) differs from the original by Hirschi and colleagues (2018) in several features. Instead of assessing organizational support and job challenge, which may not be appropriate for students attending their first year of university, as they may have not been engaged in work experiences, CRQ-A (Marciniak et al., 2020) focuses on social support from family, school, and friends, which has a critical role in building youngsters’ career preparedness (Hirschi et al., 2011). Another difference from the original CRQ (Hirschi et al., 2018) regards the career management behaviors dimension, which has been slightly changed in CRQ-A. The networking ability is maintained, but career information-seeking and continuous work-related learning have been changed into career and self-exploration, which are essential features for well-informed career-related decision-making (Savickas, 2002).

The present study

The aim of the present study was to translate the CRQ-A (Marciniak et al., 2020) into Italian and test its reliability and validity among Italian first-year university students.

For our purposes, we chose to translate and validate the version by Marciniak and colleagues (2020), which we felt was more appropriate for our target, as it was devoid of job-specific references. As for our target, in fact, it consists of students who have just enrolled in their first year of university, who do not have any formal work experience behind them; they have just made their first transition from high school to university. They have already made the first choice, yet now they are called to the challenge of determining whether it was the correct one. If the answer is affirmative, they are called to prepare for future employment. If the answer is negative, they are called to retrace the career decision process. In either case, the career resources mentioned so far are essential.

Study 1—exploratory factor analysis

Method

Translation

The back-translation method (Brislin, 1970) was used. First, the 36 items chosen for the adolescent version by Marciniak et al. (2021) were independently translated by two bilingual researchers with previous experience in career guidance psychology. The two Italian translations were then compared to reach a single version, which was then back-translated into English by another researcher not involved in the study or the field of career guidance psychology. The original and back-translated versions were finally compared to reach a consensus. The wording of the items was adapted to the chosen target. Differently from the original CRQ-A (Marciniak et al., 2021), the items of the “social support from school” scale were translated using the past tense.

Participants

Study 1’s sample consists of 270 university students attending the first year of university, recruited during the opening day of the academic year, and invited to fill in the online questionnaire. Overall, 39% are male, and 61% are female. The mean age is 19.5 years old [standard deviation (SD) = 1.28], ranging from 18 to 23 years old. As for school education, 51% of the sample attended a lyceum, 44% a technical high school, and 5% a professional institute. The majority of participants (61%) had already chosen and enrolled in a degree course; the other part of the sample had not yet enrolled in a course or did not declare it. Of the students already enrolled, 33% chose a humanities degree, 31% a technical degree, 13% an economics degree, 12% a scientific degree, 9% a medical degree, and 2% a law degree course.

Measures

The CRQ-A questionnaire consists of 12 scales, each consisting of 3 items, for a total of 36 items. The scales are as follows: occupational expertise, labor market knowledge, soft skills, career involvement, career confidence, career clarity, social support from school, social support from family, social support from friends, networking, career exploration, and self-exploration. Each item is formulated as a statement toward which each subject must express their degree of agreement, and is rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true. To identify which items belonged to the scales as originally conceived by the authors, we assigned a code to each scale, as can be seen from Table 1 (the codes are explained in the footnotes).

Results

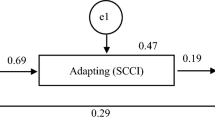

Descriptive data analysis (items’ mean and standard deviation), Pearson correlations, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and sample adequacy tests were tested through SPSS 26. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (= 0.92) was adequate, confirming data appropriateness (Hair et al., 1995). Since the wording of some items has been changed and the sample is slightly different from the original version, we chose to conduct an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to verify whether the theoretical framework proposed by the authors was also valid among young Italian first-year university students. EFA was performed using Mplus 8. The method of estimation was maximum likelihood, rotation was geomin. We ran 12 EFA, hypothesizing 1–12-factor extraction. The maximum number was given by the original study (Marciniak et al., 2020), which identified 12 subscales. The EFA on our sample, however, suggested the 10-factor solution. Also, parallel analysis, scree plot, and percentage of variance explained did not justify the extraction of 12 factors, and all supported the 10-factor solution. Table 1 shows the factor loadings, and Table 2 shows that the 10-factor solution has the best fit. Each item clustered on its respective factor in 8 cases out of the 12 original factors (Hirschi et al., 2018). Differently from the original questionnaire, the 10-factor EFA suggests the creation of two new subscales each composed of six items, merging, respectively, the original Occupational Expertise with Career Confidence subscales and Career Exploration with Self Exploration subscales. Factor loadings are all above 0.35, ranging from 0.36 to 0.94. The 10-factor solution explains 78% of the variance. All 10 subscales show good internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha values are 0.89 (labor market knowledge), 0.89 (soft skills), 0.88 (occupational expertise and career confidence), 0.80 (career involvement), 0.89 (career clarity), 0.92 (social support from school), 0.90 (social support from family), 0.88 (social support from friends), 0.86 (networking), 0.84 (career and self exploration). Finally, the 10 resulting subscales are all significantly correlated with each other, with correlation values ranging from 0.22 to 0.69.

Study 2—confirmatory factor analysis

Method

Participants

Study 2’s sample consists of 184 university students, recruited online and invited to fill in the online questionnaire. The inclusion criterion was to be enrolled in the first year of a first-level degree. Overall, 34% are male, and 66% are female. The mean age is 22 years (SD = 1.54), ranging from 19 to 25 years old. As for school education, 85% of the sample attended a lyceum, 14% a technical high school, and 1% a professional institute. The majority of participants (83%) enrolled in a humanities degree, and the other 17% in a technical degree.

Measures

Career resources

The Italian version of CRQ-A was used to assess the 10 career resources, as determined by the results obtained from Study 1. Each item was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true. All 10 subscales showed good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.83 (occupational expertise and confidence), 0.87 (labor market knowledge), 0.87 (soft skills), 0.77 (career involvement), 0.81 (career clarity), 0.91 (social support from school), 0.91 (social support from family), 0.83 (social support from friends), 0.88 (networking), and 0.80 (career- and self-exploration).

Career decision self-efficacy

The Career Exploration and Decision Self-Efficacy—Brief Decisional Self-Efficacy Scale (CEDSE-BD; Lent et al., 2016) and the Career Decision Self-Efficacy Scale (CDSES; Lo Presti et al., 2013) were used.

The scale by Lent et al. (2016) was validated on a sample of college students and consists of eight items that measure individuals’ self-efficacy about career-related decisions, considered as the set of adaptive behaviors that allow people to actively take part in the process of constructing their own career development. This career-related decisional self-efficacy is expressed through career exploration and the exploration of one’s resources in dealing with career paths that are susceptible to unpredictable changes that need to be managed. Each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert ranging from 1 = I have no confidence to 5 = I have complete confidence, and responded to the question “How much confidence do you have in your ability to…?” Examples of abilities listed in CEDSE-BD are “…pick the best-fitting career option for you from a list of your ideal careers,” and “…match your skills, values, and interests to relevant occupations.” Cronbach’s alpha value for CEDSE-BD in the present study was 0.88.

The scale by Lo Presti et al. (2013) is frequently used in career counseling and vocational guidance activities dedicated to students to assess their degree of self-efficacy and confidence regarding career-related skills. It consists of 25 items and 5 subscales, respectively: self-appraisal, occupational information, goal selection, planning, and problem-solving. The self-appraisal scale measures one’s ability to identify personal resources and limitations that might in some way influence career choices. The occupational information scale measures the perception of one’s ability to gather information about job and training offers. The goal selection scale concerns the perceived ability to focus one’s efforts on effective actions for professional development. The planning scale concerns the perceived ability to plan the steps necessary to achieve a given professional goal. Finally, the problem-solving scale measures the perceived ability to solve and deal with any career-related difficulties. Each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert ranging from 1 = I have no confidence to 5 = I have complete confidence, and responded to the question “How much confidence do you have in your ability to…?” Examples of an item for each dimension of CDSES are “…determine what your ideal job would be” (self-appraisal), “…talk with a person already employed in the field you are interested in” (occupational information), “…choose a career that will fit your preferred lifestyle” (goal selection), “…make a plan of your goals for the next 5 years” (planning), and “…change majors if you did not like your first choice” (problem-solving). The Cronbach’s alphas for the 5 subscales of CDSES were, respectively, 0.81, 0.72, 0.75, 0.80, and 0.78.

Career values

The Occupation Role Reward Value Scale (Amatea et al., 1986) was used to assess career values. The scale was validated on undergraduate students and measures the work role expectations, such as the expected satisfaction from one’s job, the importance of building a name and reputation, the feeling of being successful, and the possibility of achieving something important. The scale consists of five items, assessed through a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true. An example of an item is “It is important to me that I have a job/career in which I can achieve something of importance.” Cronbach’s alpha value in this study was 0.78.

Career control

The four-item Career Control Scale (Akkermans et al., 2013) was used. The scale was designed to measure several career competencies among young adults, such as motivation, perceived qualities, networking, self-profiling, job exploration, and career control. For the purpose of our study, only the career control subscale was selected; it measures the ability to act on work and training processes related to the career chosen or undertaken, through setting goals and planning how to achieve them. Each item was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true. An example of an item is “I can create a layout for what I want to achieve in my career.” Cronbach’s alpha value in this study was 0.83.

Networking ability

The Networking Ability Scale (Ferris et al., 2005) was used. It refers to the ability to develop contacts and relationships with a network of people and to take advantage of them for professional development. According to the conceptual framework underlying the instrument, individuals high in networking ability have an advantage in creating and seizing opportunities.Each of the four items was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true. The wording of the items was slightly modified to fit the student sample, so any reference to work was removed. An example of an item is “I spend a lot of time and effort networking with others.” Cronbach’s alpha value in this study was 0.87.

Social support

The Student Social Support Scale (SSSS; Malecki & Elliots, 1999) was used to assess students’ perceptions of the degree of social, emotional, informational, and practical support they have received from teachers, parents, and peers. Of the four original subscales (support from teachers, parents, classmates, and close friends), for the purpose of the present study only the parents, teachers, and close friends support scales were chosen, and only five items were selected for each dimension, for reasons of parsimony. Each item was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true. Examples of an item for each dimension are “My parent(s) help me find answers to my problems,” “My teacher(s) helped me solve problems by giving me information,” and “My friend(s) make me feel better when I mess up.” Cronbach’s alpha for the three subscales was 0.94 (parents’ support), 0.93 (teachers’ support), and 0.92 (friends’ support).

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to confirm the factor structure of the Italian adaptation. Mplus 8 was used, and the method of estimation was maximum likelihood. Criteria for evaluating the goodness of fit were: χ2 likelihood ratio statistic, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with associated confidence intervals, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The acceptable criteria are values ≥ 0.90 for TLI and CFI, and ≤ 0.08 for RMSEA and SRMR. Three models were tested as follows. In line with the results from the EFA in Study 1, we tested a 10-factor model in which each item loaded on its respective subdimension and was free to correlate with each other. In line with the theoretical model underlying (Hirschi et al., 2018), a four-factor model was also tested. In this model, the 12 original subdimensions loaded on four higher-order dimensions (knowledge and skills, motivation, environment, and activities), three subdimensions for each higher-order dimension, which were free to correlate with each other. Finally, we tested a one-factor solution, where each item loaded on a single factor. Indices of fit are shown in Table 3. As expected, the 10-factor model yielded the only acceptable fit. Table 4 shows the factor loadings for each item.

All 10 subscales show good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.87 (labor market knowledge), 0.87 (soft skills), 0.83 (occupational expertise and career confidence), 0.77 (career involvement), 0.81 (career clarity), 0.91 (social support from school), 0.91 (social support from family), 0.83 (social support from friends), 0.88 (networking), and 0.80 (career and self exploration).

To test the convergent validity, we correlated each subdimension with theoretically related scales. We expected occupational expertise and career confidence to positively relate to career control, planning abilities, and self-appraisal. The soft skills subdimension is expected to positively relate to self-appraisal and career problem-solving. We also expected career involvement to be positively associated with occupational role values, career clarity with the career goal selection ability, labor market knowledge with the ability to seek occupational information, career and self-exploration to be positively related to career decision self-efficacy, and so on. Table 5 reports the correlation matrix of the 10 subdimensions with their closely related constructs. All hypothesized correlations are statistically significant and, as expected, positive.

General discussion

The study aimed to validate an Italian version of the CRQ-A by Marciniak and colleagues (2020) to gain an instrument that could assess the career resources of Italian undergraduate students. The 36 items of CRQ-A (Marciniak et al., 2020) were translated into Italian, and reliability and validity were assessed through two studies. In Study 1 we conducted an EFA that highlighted some differences from the original version, suggesting a 10-factor solution instead of the original 12-factor structure. The EFA suggested merging the originally separated dimensions of occupational expertise and career confidence into a single factor, and the two subscales of career exploration and self-exploration into another single factor. The solution can be justified by the overlapping of themes. On the one hand, occupational expertise requires confidence, and career confidence requires expertise (Heijde & Van Der Heijden, 2006; Hirschi & Herrmann, 2013; Hirschi et al., 2018). Furthermore, according to some career self-efficacy models (Kossek et al., 1998; Rigotti et al., 2008), confidence is a fundamental component of the perception of self-efficacy in career management since it concerns the employees’ beliefs about their ability to manage their career and achieve work goals. Career self-efficacy, in turn, is closely related to career self-management capability, of which occupational expertise is a component. On the other hand, the two subscales relating to career and self-exploration can be jointly conceived, as exploration refers to the ability to reflect and imagine the commonality of characteristics between a career and one’s self within that career (Akkermans et al., 2018). Therefore, the union of the aforementioned four factors to create two of them does not appear to be forced, from a theoretical point of view. In our opinion, however, the different structuring of these variables is not a disconfirmation of the validity of the scales as hypothesized by the original instrument. The 10-factor structure does not contrast with Hirshi’s (2012) employability model, which theorized a configuration made up of knowledge and skills, motivation, environmental support, and career management behaviors. Furthermore, it should be considered that the original scales, taken individually, still show good internal consistency, according to the Cronbach alpha values on the sample of Study 2 (respectively, 0.65 for occupational expertise, 0.81 for career confidence, 0.81 for career exploration, and 0.76 for self exploration).

In Study 2 we collected a new sample and conducted a series of CFAs to reevaluate the proposed 10-factor structure of the Italian CRQ, which was confirmed. Convergent validity was then assessed through the analysis of the correlations between each career resource and closely related constructs.

In conclusion, considering the results and given the importance of having concise multidimensional tools, aimed at framing the complex phenomenon of career preparedness, we can affirm that the Italian version of CRQ-A can be correctly used in Italian academic contexts to investigate career resources for undergraduates. In fact, one of the strengths of the CRQ-A is the assessment of malleable characteristics of the person. The wording of the items makes it possible to assess students’ perceptions of their own career resources. In other words, it is as if they placed themselves on a linear scale that measures the degree of readiness for a future career, in which lower positions correspond to a self-diagnosed need to take action to improve lacking career skills. In fact, a preventive assessment could allow for intervention with enhancement programs included in the university curriculum on par with teaching subjects. These programs would be in addition to the university and career guidance initiatives that Italian students undertake as an integral part of their school curricula. The presence of vocational guidance courses as early as middle school is probably one of the reasons why our sample obtained high scores in several career resources, despite their young age and little or no work experience.

Practical implications

Evaluating a complex and multi-faceted phenomenon such as career preparedness and employability is probably one of the greatest challenges that higher education institutions have had in recent years. In parallel with the transmission of knowledge, modern universities increasingly offer services to support the employability of their students, also stimulated by the assessment that governments carry out on the effectiveness of academic paths, and in which the employment rate of graduates gains more and more space and weight.

Although the employability of students certainly has to do with variables beyond the control of universities, including, in particular, some psychological and social aspects, it is becoming increasingly important to have instruments that allow them to intervene early and to act through programs and ad hoc intervention that can make the career development of their students more effective. We believe that this instrument can effectively respond to this need.

Finally, possible broad-spectrum use of a questionnaire such as CRQ-A could lead to international studies that explore the impact of the perception of employability and career preparedness in different regions, and compare students’ perceptions with real employment rates so as to suggest adequate intervention strategies to political decision-makers.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations need to be considered. First of all, the CRQ is based on self-reported data and is therefore susceptible to self-report-specific bias. As suggested by the authors of the original version (Marciniak et al., 2020), CRQ should be combined with other measures that capture different points of view, such as school teachers, parents, career counselors (where applicable), and so on.

Second, a larger sample would be needed and invariance testing should be conducted to verify the consistency of scales and responses across gender and type of study.

Although broad about the constructs captured, the CRQ is certainly not an all-encompassing measure of all the facets of career preparedness. Therefore, as suggested by Marciniak and colleagues (2020) themselves, it should be combined with other measures that assess additional components.

Finally, future research should investigate the relationships between some specific subdimensions of the CRQ with outcomes such as career control or decisional self-efficacy, preferably through a longitudinal design that can capture causality relationships. From this point of view, given that a good number of the subjects who participated freely decided to provide their contact details and agreed to respond to future surveys, we intend to study, in a first step, the connection between the perception of career resources with academic success and satisfaction and, in the long term, the connection with career success.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author

References

Akkermans, J., Brenninkmeijer, V., Huibers, M., & Blonk, R. W. B. (2013). Competencies for the contemporary career: Development and preliminary validation of the Career Competencies Questionnaire. Journal of Career Development, 40(3), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845312467501

Akkermans, J., Paradniké, K., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., & De Vos, A. (2018). The best of both worlds: The role of career adaptability and career competencies in students’ well-being and performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01678

Akkermans, J., & Tims, M. (2017). Crafting your career: How career competencies relate to career success via job crafting. Applied Psychology, 66(1), 168–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12082

Amatea, E. S., Cross, E. G., Clark, J. E., & Bobby, C. L. (1986). Assessing the work and family role expectations of career-oriented men and women: The life role salience scales. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48(4), 831–838. https://doi.org/10.2307/352576

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Clements, A. J., & Kamau, C. (2018). Understanding students’ motivation towards proactive career behaviours through goal-setting theory and the job demands–resources model. Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2279–2293. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1326022

Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Kolodinsky, R. W., Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C. J., Douglas, C., & Frink, D. D. (2005). Development and validation of the Political Skill Inventory. Journal of Management, 31(1), 126–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206304271386

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907x241579

Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate Data Analysis (3rd edition). New York: Macmillan.

Heijde, C. M. V. D., & Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2006). A competence-based and multidimensional operationalization and measurement of employability. Human Resource Management, 45, 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20119

Hirschi, A. (2009). Career adaptability development in adolescence: Multiple predictors and effect on sense of power and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.002

Hirschi, A. (2012). The career resources model: An integrative framework for career counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.700506

Hirschi, A., & Freund, P. A. (2014). Career engagement: Investigating intraindividual predictors of weekly fluctuations in proactive career behaviors. Career Development Quarterly, 62(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2014.00066.x

Hirschi, A., & Herrmann, A. (2013). Calling and career preparation: Investigating developmental patterns and temporal precedence. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.02.008

Hirschi, A., Herrmann, A., & Keller, A. C. (2015). Career adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting: A conceptual and empirical investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.008

Hirschi, A., Nagy, N., Baumeler, F., Johnston, C. S., & Spurk, D. (2018). Assessing key predictors of career success: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717695584

Hirschi, A., Niles, S. G., & Akos, P. (2011). Engagement in adolescent career preparation: Social support, personality and the development of choice decidedness and congruence. Journal of Adolescence, 34(1), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.009

Jiang, Z., Newman, A., Le, H., Presbitero, A., & Zheng, C. (2019). Career exploration: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 338–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.008

Kleine, A., Schmitt, A., & Wisse, B. (2021). Students’ career exploration: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103645

Kossek, E. E., Roberts, K., Fisher, S., & Demarr, B. (1998). Career self-management: A quasi-experimental assessment of the effects of a training intervention. Personnel Psychology, 51, 935–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00746.x

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033446

Lent, R. W., Ezeofor, I., Morrison, M. A., Penn, L. T., & Ireland, G. W. (2016). Applying the social cognitive model of career self-management to career exploration and decision-making. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 93, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.007

Lo Presti, A., Pace, F., Mondo, M., Nota, L., Casarubia, P., Ferrari, L., & Betz, N. E. (2013). An examination of the structure of the Career Decision Self-Efficacy Scale (short form) among Italian high school students. Journal of Career Assessment, 21(2), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072712471506

Malecki, C. K., & Elliot, S. N. (1999). Adolescents’ ratings of perceived social support and its importance: Validation of the Student Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools, 36(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199911)36:6%3c473::AID-PITS3%3e3.0.CO;2-0

Marciniak, J., Hirschi, A., Johnston, C. S., & Haenggli, M. (2021). Measuring career preparedness among adolescents: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire—adolescent version. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720943838

McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42, 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000316100

Meijers, F. (1998). The development of a career identity. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 20, 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005399417256

Ng, T. W. H., Eby, L. T., Sorensen, K. L., & Feldman, D. C. (2005). Predictors of objective and subjective career success. A Meta-Analysis. Personnel Psychology, 58, 367–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00515.x

Praskova, A., Creed, P. A., & Hood, M. (2015). Career identity and the complex mediating relationships between career preparatory actions and career progress markers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.01.001

Rigotti, T., Schyns, B., & Mohr, G. (2008). A short version of the Occupational Self-Efficacy Scale: Structural and construct validity across five countries. Journal of Career Assessment, 16, 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305763

Santisi, G., Magnano, P., Platania, S., & Ramaci, T. (2018). Psychological resources, satisfaction, and career identity in the work transition: An outlook on Sicilian college students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 11, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S164745

Savickas, M. L. (2002). Career construction: A developmental theory of vocational behavior. In D. Brown (Ed.), Career choice and development (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Jvb.2012.01.011

Savickas, M. L., Porfeli, E. J., Hilton, T. L., & Savickas, S. (2018). The student career construction inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.009

Spurk, D., & Straub, C. (2020). Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103435

Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 580–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026423

Stringer, K., Kerpelman, J. L., & Skorikov, V. B. (2011). Career preparation: A longitudinal, process-oriented examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.012

Funding

The authors have no funding to disclose

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing: FP and GS. Data collection: FP. Data analysis: GS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Palermo Committee (protocol n. 71/2022) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pace, F., Sciotto, G. Undergraduate students’ career resources: Validation of the Italian version of the career resources questionnaire. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-023-09616-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-023-09616-9