Abstract

While narrative approaches flourish in contemporary career guidance, insufficient attention has been paid to the sensory input of narrative construction. This study concerns supporting narrative construction with visual stimuli. We examined whether image-supported storytelling preparation improved interview anxiety and performance. Using within-subject repeated measures, we found that although interview anxieties conceived by interviewees and perceived by assessors were negatively associated with interview performance, an image-supported intervention improved performance rating, appearance anxiety and assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety. Combined with practice, the intervention also alleviated other dimensions of interview anxiety, showing the value of visual input in narrative interventions.

Résumé

Utilisation de stimuli visuels dans les interventions de carrière de l’approche narrative: Effets de la narration assistée par l'image sur l'anxiété et la performance en entretien

Alors que les approches narratives fleurissent dans l'orientation professionnelle contemporaine, une attention insuffisante a été accordée à l'apport sensoriel de la construction narrative. Cette étude porte sur le soutien de la construction narrative par des stimuli visuels. Nous avons examiné si la préparation à la narration soutenue par des images améliorait l'anxiété et la performance en entretien. En utilisant des mesures répétées intra-sujet, nous avons constaté que, bien que les anxiétés liées à l'entretien conçues par les personnes interrogées et perçues par les évaluateur·trice·s étaient négativement associées à la performance de l'entretien, l'intervention soutenue par des images améliorait l'évaluation de la performance, l'anxiété liée à l'apparence et l'anxiété des personnes interrogées perçue par l’évaluateur·trice. Combinée à la pratique, l'intervention a également atténué d'autres dimensions de l'anxiété liée à l'entretien, soulignant le potentiel des interventions narratives visuelles.

Zusammenfassung

Verwendung visueller Stimuli in narrativen Karriereinterventionen: Auswirkungen von bildgestütztem Storytelling auf Interviewangst und -leistung

Während narrative Ansätze in der zeitgenössischen Berufsberatung florieren, wurde dem sensorischen Input der narrativen Konstruktion zu wenig Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. In dieser Studie geht es darum, die narrative Konstruktion mit visuellen Stimuli zu unterstützen. Wir untersuchten, ob die bildgestützte Storytelling-Vorbereitung die Angst vor Vorstellungsgesprächen und die Leistung verbessert. Unter Verwendung von wiederholten Messungen innerhalb des Subjekts stellten wir fest, dass, obwohl Interviewängste, die Interviewpartner erfahren und von Assessoren wahrgenommen wurden, negativ mit der Interviewleistung assoziiert waren, die bildgestützte Intervention die Leistungsbewertung, Erscheinungsangst und die vom Assessor wahrgenommene Angst des Interviewten verbesserte. In Kombination mit Übung linderte die Intervention auch andere Dimensionen der Angst vor Vorstellungsgesprächen, was auf das Potenzial visueller narrativer Interventionen hinweist.

Resumen

El Uso de Estímulos Visuales en Intervenciones Narrativas para la Carrera: Efectos de la Narración Basada en Imágenes sobre la Ansiedad y el Rendimiento en la Entrevista

Si bien los enfoques narrativos aumentan en la orientación profesional contemporánea, no se ha prestado suficiente atención a los estímulos sensoriales de la construcción narrativa. Este estudio trata sobre el apoyo de los estímulos visuales a la construcción narrativa. Examinamos si la preparación de la narración apoyada por imágenes mejoraba la ansiedad y el rendimiento en la entrevista. Usando medidas repetidas intra-sujeto, encontramos que aunque la ansiedad de la entrevista proyectada por los entrevistados y percibida por los evaluadores se asociaba de forma negativa con el rendimiento de la entrevista, la intervención apoyada por imágenes mejoró la calificación del rendimiento, la aparición de la ansiedad, así como la ansiedad del entrevistado que percibe el evaluador. Combinada con la práctica, la intervención también moderó otras dimensiones de la ansiedad en la entrevista, lo que apunta al potencial de las intervenciones narrativas visuales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Career counselling and guidance has taken a narrative turn in the twenty-first century (Cochran, 1997; Hartung et al., 2013). Narrative approaches are regarded as an evolutionary shift ‘from scores to stages to stories’ (Savickas, 2015), an exemplar of career constructivism (McIlveen & Patton, 2007), a way to craft stories of identifies with diverse clientele (McMahon & Watson, 2012; McMahon et al., 2020), a process of re-scripting personal growth and wellbeing (Bauer & McAdams, 2010), a tool for inclusive and sustainable career counselling (Santilli et al., 2021) and a dynamic addition to career service delivery (Amundson, 2006). However, despite the growth of narrative counselling and guidance, the lack of attention paid to the sensory input of narrative construction is significant. Given that the basis of narratives experiences is multi-sensory (Gonçalves and Machado 1999; Gonçalves et al., 2004), a fuller understanding of sensory input into narrative construction will be key to optimising narrative-based guidance and skills training.

Visual stimuli have been the most prominent sensory input found in narrative-based interventions in general. In therapeutic and educational settings, visual methods have been used in narrative applications for client engagement, meaning construction, behaviour internalisation, problem reframing and reality re-scripting (Lin-Stephens, 2020a). Visual artefacts supporting these processes range from simple objects such as photos, pictures, pictorials, paintings and drawings (Adenauer et al., 2011; Garwolińska et al., 2018; Gunnarsson & Bjórklund, 2013; Lerner, 1979; Nguyen, et al., 2018; Ziller, 2000), multimedia such as videos and games (Cheng, 2019; Grassi et al., 2011; Heilemann et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018), to elaborate technologies such as augmented and virtual reality (Ahn & Lee, 2013; Falconer et al., 2017; Juan & Pérez, 2010; McNamara et al., 2018; Morina et al., 2014). Overall, various types of visual artefacts have contributed to narrative interventions addressing diverse anxiety conditions (Lin-Stephens, 2020a).

The success of visual methods may be understood in terms of cognitive psychotherapy, neuroscience and social psychology. An underlying tenet across these perspectives is that an individual’s existence is inseparable from their sensing and knowing. There is a strong connection between the senses, knowledge construction, memory retrieval and the re-experience of events. Cognitive narrative psychotherapy (Gonçalves and Machado 1999; Gonçalves et al., 2004) contends that sensory input provides details that enable individuals to build representations of events objectively and subjectively. Thus, realities can be re-interpreted and re-constructed to form alternative narratives. Neuroscience imaging research, notably the constructive episodic simulation hypothesis, adds that past and future event thinking operates from a common neural mechanism of memory that enables information to be used flexibly to form coherent simulations of events (Addis & Schacter, 2008; Schacter & Addis, 2007). Sensory aids such as visual details may enable ‘mental time travel’ to revisit and re-imagine past events (Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007).

It follows that visual artefacts may provide individuals with the tangible means to manipulate the psychological distance of events. In construal level theory (Trope & Liberman, 2010, 2012), thinking and remembering involve traversing psychological distances of mental constructs. The more abstract a concept is, the higher the construal level, and the farther the psychological distance. Psychological proximity and construal levels are associated with individuals’ emotional intensity, decision making and performance (Polman & Emich, 2011; Thomas & Tsai, 2012; Van Boven et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2014). Based on this theory, visual stimuli may be used to shorten psychological distances with detailed, concrete low-level construals, or vice versa, lengthen the distances with temporally or socially decontextualised, abstract high-level construals. Thus, visual stimuli present an opportunity to support the recall and reconstruction of narratives in situations where narrative construction can be a challenge.

Image-supported interview storytelling

A significant area of career interventions that may benefit from visual narrative applications is the selection interview. Selection interviews are occasions of serious storytelling demanding thoughtful, impressive and impactful narratives (Lugmayr et al., 2017). Graduate employers in the private and public sectors routinely rely on substantial past event narratives in job applications and interviews to assess candidates’ experience, skills and attributes (Australian Public Service Commission, 2020; Forbes, 2020; Government of Canada, 2019; UK Government, 2016; US Department of Labor, 2019). However, individuals differ in narrative skills and the ability to cope with situations that are highly evaluative, competitive and consequential (Feeney et al., 2015; Feiler & Powell, 2013; Peterson, 1997). Even in behavioural interviews, where narratives from the past are explicitly required, it has been shown that past event stories only accounted for few interview responses (Bangerter et al., 2014). The truism that ‘practice makes perfect’ is also unsupported in empirical studies (Williams, 2008, 2012). Although interviewer feedback and probing have been found to be helpful in enhancing interview responses (Brosy et al., 2020; Williams, 2008), interviewees cannot depend on interviewers’ probing or feedback during interviews; therefore, self-reliant methods of pre-interview preparation must be sought. Given that interviews predicate skill articulation upon past event narratives (Goodwin et al., 2019; Tross & Maurer, 2008), there exists a risk of poor interview narratives and performance jeopardising selection outcomes. Consequently, there exists a need to support interviewees in recalling significant past events and communicating interview stories effectively.

Recent experimental studies have found incorporating images into interview preparation beneficial to interview storytelling by reducing performance anxiety (Lin-Stephens et al., 2022a) and enhancing written narrative quality (Lin-Stephens et al., 2022b). In these studies, past behavioural interview skills training was given to experimental and control groups, under the experimental condition of using images during private preparation. The preparation involved using an observable image to match an interview narrative. The brief intervention was found to have extended the effects of interview training. Visual cues may have enabled the re-engagement of prior experiences and the ‘adjectifying’ of realities (Gonçalves et al., 2004); thereby, enriching memory and narrative reconstruction. Considering findings from these studies, further investigation into the full dimensions of interview anxiety and performance with oral response delivery is necessary to address key concerns of interview skills training provision, namely, interview anxiety and performance (Huffcutt et al., 2011; Jeske et al., 2018).

Interview anxiety

Interview anxiety is a key predictor of interview performance and can affect interviewees with and without pre-existing anxiety conditions (Behroozi et al., 2020; Powell et al., 2018). Interview anxiety is a situation-specific trait encompassing ‘feelings of nervousness or apprehension that are relatively stable within job applicants across employment interview situations’ (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004, p. 616). This situation-specific trait is important in the understanding and subsequent management of interview anxiety and performance (Constantin et al., 2021; Schneider et al., 2019). From a state anxiety perspective (Spielberger, 1985), interview anxiety is regarded as synonymous with situational, test anxiety (Kowal & Shukla, 2021; McCarthy & Goffin, 2005; Proost et al., 2008); therefore, interventions such as emotional regulation strategies or test-taking skills could be used to cope with interview anxiety (Edgemon et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2016). Yet, like test anxiety, the anxiety experienced during interviews interacts with stable trait qualities, such as cognitive abilities, gender-linked coping styles and personality (Bourdage et al., 2020; Feeney et al., 2015; Huffcutt, et al., 2017; McCarthy & Goffin, 2005). Thus, corresponding interventions can have a broader aim of increasing clients’ experience and capacity, in addition to developing situation-specific skills (Krishnan, et al., 2021; McGovern et al., 1981; Roberts, 2012).

In considering the relationship between interview anxiety and performance, it is important to note that both anxieties conceived by interviewees and perceived by assessors can affect performance ratings (Constantin et al., 2021; Huffcutt, 2011). Assessor responses are known to have affected interviewees’ stress levels and performance (Budnick et al., 2015, 2019). On the one hand, assessors can view anxious signs of the interviewees as a lack of confidence, not telling the truth or possessing inadequate communication skills (Kraut, 1978; Lord et al., 2019). On the other hand, empathetic assessors could overcompensate applicants’ anxious behaviours and inflate the performance rating (Sydiaha, 1962). Either way, how assessors perceive interviewee anxiety is an important consideration because of their verbal and non-verbal reactions that can further affect interviewee anxiety and performance (Feiler & Powell, 2016).

Interview performance

Overall, interview performance judgement centres on the idea of hirability (Williams, 2008). Hiring offers, or acceptance, have been regarded as the ultimate yardstick of interview success in some studies (Anderson & Shackleton, 1990; Hosoda & Stone-Romero, 2010; Kausel et al., 2016). This reflects the common, if not the only, goal of interviews being to secure job offers for interviewees and make hiring decisions for interviewers. However, in the training and intervention context, interview performance cannot be conflated with job offers, because non-performance factors such as pragmatic considerations, bias and unfair discrimination can affect interview outcomes, regardless of performance (Alonso & Moscoso, 2017). Thus, interview performance evaluation based on likelihood to hire, which is still intuitive but not binary, has also been found in the literature (Russell et al., 2008).

Recent studies have relied on diverse measures of hirableness, using structured and pre-determined criteria to evaluate competency, skills, quality and suitability (Alonso & Moscoso, 2017; Budnick et al., 2019; Hosoda & Stone-Romero, 2010; Nguyen et al., 2014). The hirableness approach has been used in studies examining interviewer verbal and non-verbal behaviours (Budnick et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2014), interview types and formats (Alonso & Moscoso, 2017), impression management and emotion regulation (Brown et al., 2010; Sieverding, 2009). However, while proxy measures of hirableness exist in abundance, descriptors of interviews as a narrative performance are yet to be consolidated. Reviews of relevant studies suggest that the judgement of interviews as a narrative performance should cover response content, delivery and interviewee demeanour to adequately evaluate verbal and non-verbal characteristics of performance (DeGoot & Motowidlo, 1999; Feiler & Powell, 2016; Hartwell et al., 2019; Hollandsworth et al., 1979; Peeters & Livens, 2006).

The present study

This study seeks to contribute to the evidence base of using sensory stimuli, particularly visual stimuli, in narrative career interventions. Given the results of recent experimental studies confirming the effects of image-supported interview storytelling preparation (Lin-Stephens et al., 2022a, b), the objective of this study is to build on the existing findings and attend to several significant considerations not addressed previously. The first is the inclusion of assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety because of its potential effects on interviewee anxiety and the subsequent performance rating. The second is to provide and apply high-level performance judgement criteria in the context of interviews as a narrative performance. Finally, for a fuller evaluation of predictors of intervention outcomes, effects of repeated practice will be considered, along with assessor-perceived interview anxiety, interviewee generalised anxiety, assessor and selective interviewee factors, such as age, gender, paid work experience, previous interview experience and future intention of work.

Assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety

The extent to which interview anxiety experienced privately corresponds to any such anxiety exhibited publicly requires examination. Preliminary evidence, presented by Feiler and Powell (2013), suggests that incongruence exists between interview anxiety as experienced by interviewees and perceived by assessors. The human visual system is programmed to judge others based on what one can see; whilst judging oneself based on what one thinks and feels (Pronin, 2008). Phenomenologically, the interviews are the experience of the interviewer and the interviewee (Kvale, 2007). The extrospection that preoccupies the interviewer and the introspection that concerns the interviewees contribute to the discrepancy between anxiety perceived by interviewers and conceived by interviewees. Thus, it is important to discern whether intervention effects on interview performance are the result of a direct reduction in interviewee anxiety or indirect mediation through the management of perceptible anxiety.

Judging criteria of interviews as a narrative performance

Employers commonly adopt the past behaviour interview method which uses storytelling to substantiate claims of employability. This method renders interviews a narrative performance and has been found to have predicted job performance and minimised the risk of confounding performance measurement with cognitive ability, as in the case of situational interview methods (Krajewski et al., 2006). Consolidating the performance indicators in previous studies, narrative conformity, overall quality and visual communication are proposed to form broad categories of assessment items to judge the interview as a narrative performance (Feiler & Powell, 2016; Hartwell et al., 2019; Peeters & Livens, 2006). Narrative conformity denotes the inclusion of past stories in a behavioural format, with details of orientation, complication and resolution. It is signified by distinct, parsimonious descriptions that illustrate the situation, task, action and result of an event. The performance judgment is characterised by completeness, concreteness, coherence and conciseness of the narratives. Overall quality refers to the combination of response relevance, appropriateness, effective vocal delivery and impressiveness. It involves positive self-promotion, tone, vocal projection and fluency. Visual communication refers to the interviewee’s appropriate demeanour and effective use of body language and composure.

Repeated practice

Although ‘practice makes perfect’ is a widely accepted belief (Ross & Moffatt, 2018), several experimental studies have found practice with negligible benefits in assessor-rated job interview simulations (Harrison, 1983; Williams, 2008, 2012). Decades after the comment made by Sacket et al. (1989) that practice effects received hardly any attention in the employment selection literature, little new evidence has been produced to clarify the effect of practice, except where practice served as a control condition to verify the effects of other interventions, such as computer-simulated interview practice (Humm et al., 2014). Given the lack of continual observations in these studies, a study design involving repeated measures of baseline, repeated practice and repeated practice with intervention may be considered for participants to act as their own control, rendering no group variance, to observe the effect of practice.

Research questions

As the different types of anxiety involved in this study were likely to be correlated, the relationships between the intervention, types of interview-related anxiety, selected covariates and interview performance are expected to be dynamic and complex. Several research questions are posed to clarify the relationships between the covariates and outcomes.

-

1.

Does assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety significantly correlate with interviewee generalised anxiety (trait based) and interview anxiety (state based)?

-

2.

Does assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety significantly correlate with other assessor-rated performance indicators?

-

3.

Does repeated practice predict improved interview anxiety and performance?

-

4.

Does the image-supported storytelling intervention predict improved interview anxiety and performance?

-

5.

Do other covariates predict improved interview anxiety and performance?

Method

The study design was within-subject repeated measures over 3 weeks. The setting was an industry placement programme organised by a research-intensive university in Australia. In this programme, applicants undergo an interview as the final step of application and selection. Face-to-face, structured behavioural interviews were employed, based on recommendations from previous studies to avoid confounding factors present in other modes of interview (Alonzo & Moscoso, 2017; Zielinska et al., 2021). The study received human ethics approval from (Macquarie University, Ref no. 5201830874476).

Participants

All 16 participants in the industry placement application programme, balanced in male to female ratio, consented to participate in the study and for their application data to be used for research purposes. Nine of the participants were of the age 25 years and seven were over the age of 25 years. Of the 16 participants, four were identified as having mild (n = 1), moderate (n = 2) and severe anxiety (n = 1) according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). All but one participant did not have recent part-time work experience. The participants’ work experience ranged from none to 10–15 years, with the mode of 4–5 years in total work history. The mean of participants’ total number of interview experiences was 4.8, with 0 being the minimum and 10 being the maximum. All participants planned to work upon degree completion; half of them also considered pursuing further studies.

Measures

Interviewee generalised anxiety

Table 1 presents five common self-rated anxiety measures considered for this study. Based on the minimum intervention needed for change design principle (Glasgow, et al., 2014), only self-rated measures are considered; therefore, clinician-rated scales such as the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1959) were excluded. Table 1 summarises the selection considerations and comparison of relevant measures. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A) (Zigmond & Smaith, 1983) was adopted for its ease of use, recency, coverage of response items, internal consistency, reliability and concurrent validity (Julian, 2011). Good validation evidence across different languages and settings provided additional justification for the choice of HADS-A (Bjelland et al., 2002; Bocéréan & Dupret, 2014; Snaith, 2003). The HADS-A was also an anxiety measure used commonly in the participants’ health care settings.

Interview anxiety – five dimensions

Participants’ state-based, situational interview anxiety was measured using Measure of Anxiety in Selection Interviews (MASI). The MASI has been widely used in interview anxiety studies, with internal consistency ranging from 0.69 to 0.83 and correlations of 0.37–0.86 across the five dimensions (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004). The MASI measured interview anxiety in five dimensions: communication anxiety, social anxiety, performance anxiety, behavioural anxiety and appearance anxiety. Each dimension contains six response items. Participants in this study used a visual analogue scale with a 100 mm line segment to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the statements regarding the interview experience they just had, from ‘not at all’ to ‘completely’.

Assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety

Considering that performance evaluation was an assessor’s priority and to avoid excessive attention paid to anxiety observation, a summative impression of perceived anxiety drawn from the relative percentile method was adopted (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004). Interviewers' direct observation was used (Jersild & Meigs, 1939; Thompson & Borrero, 2011) to indicate assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety on a scale of 0–100, with 0 denoting no anxiety present at all, 100 denoting extreme anxiety and a descriptor anchor of ‘average’ assigned to the score of 50 (Melchers et al., 2021). This method of direct report simulated a naturalistic evaluation by assessors in job interviews.

Interviewee performance

The assessors rated interviewee performance according to the judgment criteria of narrative conformity (complete, concrete past examples with details of situation, task, action and result), overall quality (appropriateness, relevance, positive self-promotion, tone, vocal projection and fluency) and visual communication (composure and effective body language). For each criterion, the assessors independently indicated their rating on a visual analogue scale of 0–100, with a descriptor anchor of ‘average’ assigned to the score of 50 (Melchers et al., 2021). The relative percentile method (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004) was adopted to measure interviewee performance for consistency.

Procedures

Participants completed HADS-A 1 week before attending their first individual interviews with two independent assessors. Participants were instructed to give specific, concrete examples to address the placement criteria. They attended the first interview under the condition of no intervention. In the second week, participants repeated the interview still with no intervention. In the final week, all participants were given the serious storytelling training that required participants to use images for interview preparation (Lin-Stephens, 2020b). This marked the third interview under the condition of repeat with intervention.

The training was a 1 hour behavioural interview training characterised by low intensity, costs, resources and complexity, according to the principles of minimum intervention needed for change (Glasgow et al., 2014). Participants were to think of a past example they would give and produce an image corresponding to the event. Participants were free to use any images that reminded them of the examples they wish to give during the interviews. The images were for participants’ private preparation only and not to be shared with the interviewers. Participants submitted a copy of the images to a research coordinator independent from the assessors as proof of compliance with the instruction. Following each interview, participants completed MASI.

A panel of two independent assessors asked each participant criteria-specific questions in three weekly interviews. The assessors were one male and one female in mid to late thirties, both with over 10 years’ work experience. Both had experience in interviewing and hiring staff and held degrees in Master of Business Administration including human resource and organisational behaviour subjects. The assessors were given training about the placement application, selection process and rating method. Both were blind to the study design.

Data analysis

Ordinal regression for continuous responses was used to analyse the visual analogue scale data (Manuguerra et al., 2020). Analyses were performed in R (R Core Team, 2020) using the package of ordinalCont (Manuguerra & Heller, 2020). The model included interviewee generalised anxiety, number of repeated practice, interview anxiety in five dimensions, assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety, the image-supported interview storytelling intervention, and other selected assessor and interviewee factors. The effect size of significant predictors was calculated by comparing the predicted outcomes either across levels of categorical predictors (e.g. treatment conditions) or for a quartile change (median to upper quartile) for continuous predictors, with the other variables fixed at their reference or median value. The longitudinal nature of the study was taken into account modelling repeated observations with random effects.

Results

Table 2 summarises the participants’ self-reported interview anxiety in five MASI dimensions at 1 week intervals.

Table 3 presents interview performance and perceived anxiety outcomes rated by assessors. Intra-class correlation coefficient showed excellent inter-rater consistency of 0.929, 95% confidence interval 0.905, 0.946, based on a mean rating (k = 2), consistency, two-way mixed-effects model (Koo & Li, 2016).

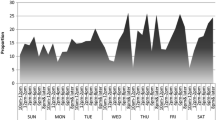

Correlation between interview anxiety, generalised anxiety and assessor-perceived anxiety

Figure 1 shows the highly significant and strong correlations between all dimensions of interview anxiety (Dancey & Reidy, 2007). Internally, the five dimensions of interview anxiety had significant moderate-to-strong correlations with each other, with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.928). Significant, moderate correlations also existed between interview anxiety and assessor-perceived anxiety. Of the five interview anxiety dimensions, only communication anxiety did not correlate significantly with generalised anxiety (r = 0.15, p = 0.323). Generalised anxiety also did not correlate significantly with assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety (r = 0.11, p = 0.447).

Correlation between assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety and interview performance rating

The four assessor-rated items significantly and strongly correlated with each other (Table 4), with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.906). Assessor-perceived anxiety significantly and negatively correlated with all three interview performance indicators, the highest being visual communication (r = −0.91). The three interview performance indicators also correlated significantly and strongly with each other. Narrative conformity was strongly correlated with overall quality (r = 0.88).

Effects of repeated practice

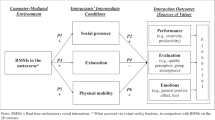

Table 5 outlines the significant results of all covariates. Figure 2 illustrates the paths and directions of the effects. Repeated practice was associated with improved communication, social and performance anxiety. With the intervention, repeated practice also predicted improved behavioural anxiety, in addition to communication, social and performance anxiety. No direct association between repeated practice and performance was found.

Effects of the intervention

The image-supported intervention was the strongest predictor of all assessor-rated items, including assessor-perceived anxiety and outcomes of narrative conformity, overall quality and visual communication. For self-reported items, the intervention was the factor that predicted appearance anxiety. Coupled with repeat practice, the intervention was also associated with improved communication, social, performance and behavioural anxiety. Comparing the effects of repeated practice and repeated practice with intervention, the latter had much stronger and more significant results in mediating communication, social and performance anxiety.

Effects of other covariates

Communication anxiety was significant in predicting all three performance indicators of narrative conformity, overall quality and visual communication. Some participant characteristics, i.e. age, gender and paid work experience affected visual communication (gender and paid work experience) and overall quality (age). One assessor was found to have consistently rated overall quality and visual communication higher than the other assessor.

Discussion

The image-supported storytelling was found to have improved interview performance and anxiety, directly and indirectly, lending support to using visual stimuli in narrative career interventions. The intervention directly predicted all assessor-rated outcome variables including interview performance and assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety. The intervention also directly predicted an improvement in self-reported appearance anxiety. Combined with repeated practice, the rest of the interview anxiety dimensions were improved.

Consistent with findings from the limited research on interview practice effects, repeated practice did not have a direct effect on improved performance. The intervention predicted all assessor ratings, including assessor-perceived interviewee anxiety and interview performance items, while communication anxiety also predicted interview performance items. The image-supported intervention was the strongest predictor of performance. Between the treatment conditions, it was clear that repeated practice with the intervention had more significant and stronger effects than repeated practice alone. When combined with the intervention, repeated practice was associated with improved communication, social, performance and behavioural anxiety, and may potentially affect performance indirectly via reduced communication anxiety. Consistent with previous research findings, communication anxiety had a negative association with interview performance (Budnick et al., 2019; McCarthy & Goffin, 2004). However, communication anxiety may be mediated by practice and repeated practice with the intervention.

The interviewees’ generalised anxiety was not significant in predicting interview anxiety or performance. This was not consistent with findings from other studies that associated trait anxiety with lower ratings of interview performance (Huffcutt et al., 2011; McCarthy & Goffin, 2004). This could be because most of the participants did not qualify as having generalised anxiety according to HADS-A. Still, significant, weak-to-moderate correlations were found between interviewee generalised anxiety and interview anxiety. Although interview anxiety had moderate correlations with both generalised anxiety and assessor-perceived anxiety, it appeared that while the assessors were able to detect interview anxiety, they did not necessarily pick up on the interviewee’s generalised anxiety. This finding suggests an opportunity for training and interventions to improve interview performance ratings. Given that assessor perception is a significant factor in the equilibrium of interview anxiety and performance, the result that the intervention was able to affect assessor perception of interviewee anxiety highlights the potential of visual narrative interventions for impression management (Budnick et al., 2015; Powell et al., 2020). Affecting generalised or trait anxiety was hardly an objective of interview anxiety interventions; rather, enabling participants to manage situations with perceived anxiety could be an aim of interventions. In addition, the fact that the intervention and communication anxiety were the main contributors to the assessor-rated outcomes highlighted the value of using communication-enabling interventions to enhance performance. These findings lend support to the idea that interventions focusing on effective narrative communication may benefit performance regardless of interviewees’ generalised anxiety and assessor-perceived anxiety.

Males performed lowered than females in visual communication, which was not a surprising result (Feiler & Powell, 2013). Intriguingly, the age of 26 years and over was associated with a slightly less overall quality rating. Work experience of 5 years and over was associated with a lower visual communication rating. These results suggest that age and work experience cannot be taken for granted as an indication of superior interview performance. Factors such as intervention, training and efforts may enable younger or less experienced interviewees to perform better than older or more experienced interviewees.

Findings from this study may inform further hypotheses to explain the effects based on the postulations of cognitive narrative psychotherapy, constructive episodic simulation hypothesis and construal level theory. Following cognitive narrative psychotherapy, the significant difference made by the minimal visual intervention may have been the result of sensory input’s close connection with the expression of significant event details (Gonçalves and Machado 1999; Gonçalves et al., 2004). The sensory basis of narratives may have activated the re-experiencing of events in new ways to benefit present storytelling, using hindsight to inform foresight, according to constructive episodic simulation hypothesis (Addis & Schacter, 2008; Schacter & Addis, 2007). Finally, the image-based intervention may have illuminated a potential underlying effect mechanism based on psychological distance and construal levels. Abstract, high-construal-level images may have been associated with greater psychological distance; hence, less anxiety. Detailed, low-level-construal images may have reflected closer psychological proximity; therefore, more vivid descriptions and better performance. A substantial number of images will be needed to differentiate image use and confirm the effect mechanism of image-supported storytelling.

Contributions

The primary contribution of this study is to demonstrate the effects of a brief visual narrative-based intervention on interview anxiety and performance. The outcomes show that it is possible to use everyday visual artefacts such as images in a minimal intervention to make noticeable differences. The findings add to the evidence base of using visual stimuli in narrative career intervention as an effective way to manage interview anxiety and performance. The observed effects of images have implications for education and employability technology development. Eportfolio, for example, can be conceived as a vehicle with sensory-enriched media to support storytelling for career and employability development.

In addition, this study fills several other gaps in the interview research literature. It provides further evidence of the effect of practice in interviews. Although practice did not translate into performance directly, repeated practice was shown to have improved communication, social and performance anxiety. Combined with the image-supported intervention, practice also had an effect on behavioural anxiety. The extent to which practice may mediate interview anxiety dimensions was more significant when supported by the intervention. Using repeated practice and the image-supported intervention, improvement in all interview anxiety dimensions could be observed. Reduced communication anxiety via practice may also potentially mediate interview performance.

This study also contributes to a relational model of interviewee anxiety, with further delineation of interviewee anxiety conceived covertly by interviewees and perceived overtly by interviewers (Weierich et al., 2008). The concept and percept-based information processing distinguished by Alexander and Baggetta (2014) may shed some light on an inclusive view of interviewers’ perception of interviewee anxiety. Figure 3 incorporates these anxiety elements in interviews to support a tripartite interview performance framework (Constantin et al., 2021). The assessors primarily cue in on the interviewee’s anxiety at an impressionistic, perceptual level (Budnick et al., 2019), while the interviewees bear the anxiety at a higher conceptual and schematic level (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004), both of which can affect interviewee performance.

Limitations

Despite the positive results, there were several significant limitations to this study. This quasi-experimental study did not contain a control group due to the small sample size. Although two previous experimental studies using control and placebo groups confirmed image exposure as superior in enhancing interview narrative quality, performance anxiety and interview performance (Lin-Stephens et al., 2022a, b), a replication study with a larger sample size could enable the inclusion of a control group and increase generalisability. The number of observations also limited our ability to refine the prediction of intervention and covariate effects. Additionally, although using the same interviewers minimised rater variability and had the relative advantage of consistent benchmarking over time, doing so might compromise external validity because most interviews were one-off transactions. The fact that the participants saw the same interviewers in consecutive weeks also meant that familiarity could be a confounding variable. Other potential confounding variables could include interview order (Frieder et al., 2016) and interviewer characteristics (Carless & Imber, 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Kausel et al., 2016). The findings also cannot be applied to non-behavioural interviews, such as situational interviews in which past stories were not the focus (Latham et al., 1980).

Future research directions

Future research is necessary to improve the generalisability of the findings in this study by increasing the sample size and the number of observations. Interviews are dynamic situations of interpersonal interaction and social exchange. Met with the versatility of visual stimuli, narrative-based applications will need a substantial number of studies to piece together factors contributing to productive interview experiences. In addition, alternative response formats, interviewee and interviewer characteristics, and variability of anxiety conditions are amongst the potential covariates to study. Once a body of evidence materialises, characteristics of the image use must be studied further to identify the effect mechanism of visual stimuli in narrative interventions. This will be crucial to the development of visual narrative interventions in theory and practice.

Conclusion

The selection interview as a form of serious storytelling shifts the intervention paradigm from question-answering to story sharing (Lugmayr et al., 2017; White & Epston, 1990). The interview as a narrative performance approach enables the narrator to rescript the interview discourse as one where they can have autonomy and control. This study provides evidence for using visual stimuli to support narrative-based career interventions that help interviewees gain a sense of control in the management of anxiety and performance. Results of the study support previous findings that a negative association exists between interview anxiety and performance (Carless & Imber, 2007; Feiler & Powell, 2016; Powell et al., 2018). This study also provides new evidence of a negative association between assessor-perceived interview anxiety and performance rating. Despite these associations, the image-supported serious storytelling intervention remains a strong and direct predictor of improved interview performance. The intervention also mediates the negative relationship between interview anxiety and performance by way of improved communication anxiety with practice. Further, a more nuanced understanding of the truism that ‘practice makes perfect’ is presented. Practice is not a direct predictor of performance in this case; however, coupled with the intervention, practice may mediate communication anxiety to influence performance outcomes.

The findings of this study support the use of basic artefacts to visualise event occurrence and support memory retrieval (Anderson & Conway, 1993; Labov & Waletzky, 1967). Researchers and practitioners have long availed themselves of diverse visual artefacts in training, using exposure therapy, emotion and attention regulation, and memory recall to improve anxiety and performance (Baert et al., 2012; Gong et al., 2016; Lapointe et al., 2013; Tross & Maurer, 2008). Although elaborate virtual simulations may offer graphical realism and a sense of presence in exposure therapies that address social anxiety in interviews (Kwon et al., 2013; Morina et al., 2014), everyday visual artefacts such as images can still be valuable to interventions aiming to improve anxiety and performance. In addition, low-technology visual stimuli present fewer barriers and more scalability for intervention administrators and users.

Multi-sensory narrative career interventions are worthy of further exploration. As the world becomes increasingly visualised through the pervasive use of multimedia technology, visual methods are well placed to enhance client engagement and facilitate behavioural, psychological and cognitive changes. Further studies may elaborate on the mechanism of image effects on interview performance, given that the image-supported intervention was much more powerful than practice alone. The range of diverse visual artefacts could be expanded to compare efficacy and suitability. This will have implications for narrative intervention development as well as therapeutic and educational technology design.

References

Addis, D. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). Constructive episodic simulation: Temporal distance and detail of past and future events modulate hippocampal engagement. Hippocampus, 18(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20405

Adenauer, H., Catani, C., Gola, H., Keil, J., Ruf, M., Schauer, M., & Neuner, F. (2011). Narrative exposure therapy for PTSD increases top-down processing of aversive stimuli-evidence from a randomized controlled treatment trial. BMC Neuroscience, 12(1), 127–127. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-12-127

Agresti, A., & Tarantola, C. (2018). Simple ways to interpret effects in modeling ordinal categorical data. Statistica Neerlandica, 72(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/stan.12130

Ahn, J. C., & Lee, O. (2013). Alleviating travel anxiety through virtual reality and narrated video technology. Bratislava Medical Journal, 114(10), 595–602. https://doi.org/10.4149/BLL_2013_128

Alexander, P. A., & Baggetta, P. (2014). Percept-concept coupling and human error. In D. N. Rapp & J. L. G. Braasch (Eds.), Processing inaccurate information: Theoretical and applied perspectives from cognitive science and the educational sciences (pp. 297–328). MIT Press.

Alonso, P., & Moscoso, S. (2017). Structured behavioural and conventional interviews: Differences and biases in interviewer ratings. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 33(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2017.07.003

Amundson, N. (2006). Challenges for career interventions in changing contexts. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 6(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-006-0002-4

Anderson, N., & Shackleton, V. (1990). Decision making in the graduate selection interview: A field study. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00510.x

Anderson, S. J., & Conway, M. A. (1993). Investigating the structure of autobiographical memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19(5), 1178–1196. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-7393.19.5.1178

Australian Public Service Commission. (2020). Applying for an APS job: Cracking the code. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://www.apsc.gov.au/working-aps/joining-aps/cracking-code/3-applying-aps-job-cracking-code.

Baert, S., Casier, A., & De Raedt, R. (2012). The effects of attentional training on physiological stress recovery after induced social threat. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25(4), 365–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2011.605122

Bangerter, A., Corvalan, P., & Cavin, C. (2014). Storytelling in the selection interview? How applicants respond to past behaviour questions. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(4), 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9350-0

Bauer, J. J., & McAdams, D. P. (2010). Eudaimonic growth: Narrative growth goals predict increases in ego development and subjective well-being 3 years later. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019654

Behroozi, M., Shirolkar, S., Barik, T., & Parnin, C. (2020). Does stress impact technical interview performance? In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium, Nov. (pp. 481–492). https://doi.org/10.1145/3368089.3409712.

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

Bocéréan, C., & Dupret, E. (2014). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in a large sample of French employees. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0354-0

Bourdage, J. S., Schmidt, J., Wiltshire, J., Nguyen, B., & Lee, K. (2020). Personality, interview performance, and the mediating role of impression management. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93, 556–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12304

Brosy, J., Bangerter, A., & Ribeiro, S. (2020). Encouraging the production of narrative responses to past-behaviour interview questions: Effects of probing and information. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(3), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2019.1704265

Brown, T., Hillier, T.-L., & Warren, A. M. (2010). Youth employability training two experiments. Career Development International, 15(2), 166–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011040950

Budnick, C. J., Andersont, E. M., Santuzzi, A. M., Grippo, A. J., & Matuszewich, L. (2019). Social anxiety and employment interviews: Does nonverbal feedback differentially predict cortisol and performance? Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806

Budnick, C., Kowal, M., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2015). Social anxiety and the ironic effects of positive interviewer feedback. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 28(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2014.919368

Carless, S. A., & Imber, A. (2007). The influence of perceived interviewer and job and organizational characteristics on applicant attraction and job choice intentions: The role of applicant anxiety. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 15(4), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2007.00395.x

Chen, C. C., Wen-Fen Yang, I., & Lin, W.-C. (2010). Applicant impression management in job interview: The moderating role of interviewer affectivity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 739–757. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X473895

Cheng, V. W. S. (2019). Gamification in apps and technologies for improving mental health and well-being: Systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 6(6), e13717. https://doi.org/10.2196/13717

Cochran, L. (1997). Career counseling: A aarrative approach. Sage.

Constantin, K. L., Powell, D. M., & McCarthy, J. M. (2021). Expanding conceptual understanding of interview anxiety and performance: Integrating cognitive, behavioural, and physiological features. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 29, 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12326

Dancey, C. P., & Reidy, J. (2007). Statistics without maths for psychology. Pearson education.

DeGroot, T., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1999). Why visual and vocal interview cues can affect interviewers’ judgments and predict job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(6), 986–993. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.6.986

Dunstan, D. A., & Scott, N. (2020). Norms for Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale. BMC Psychiatry, 20, 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2427-6

Edgemon, A. K., Rapp, J. T., Brogan, K. M., Richling, S. M., Hamrick, S. A., Peters, R. J., & O’Rourke, S. A. (2020). Behavioural skills training to increase interview skills of adolescent males in a juvenile residential treatment facility. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 53(4), 2303–2318. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.707

Falconer, C. J., Cutting, P., Davies, E. B., Hollis, C., Stallard, P., & Moran, P. (2017). Adjunctive avatar therapy for mentalization-based treatment of borderline personality disorder: A mixed-methods feasibility study. Evidence Based Mental Health, 20(4), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102761

Feeney, J. R., McCarthy, J. M., & Goffin, R. (2015). Applicant anxiety: Examining the sex-linked anxiety coping theory in job interview contexts. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 23(3), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12115

Feiler, A. R., & Powell, D. (2013). Interview anxiety across the sexes: Support for the sex-linked anxiety coping theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2012.07.030

Feiler, A. R., & Powell, D. M. (2016). Behavioural expression of Job Interview anxiety. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(1), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9403-z

Forbes. (2020). Good STAR stories matter, especially in virtual interviews. Retrieved from May 1, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/juliawuench/2020/07/16/good-star-stories-matter-especially-in-virtual-interviews/?sh=54a3d02c7418.

Frieder, R. E., Van Iddekinge, C. H., & Raymark, P. H. (2016). How quickly do interviewers reach decisions? An examination of interviewers’ decision-making time across applicants. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(2), 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12118

Garwolińska, K., Oles, P. K., & Gricman, A. (2018). Construction of narrative identity based on paintings. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(3), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1370693

Glasgow, R. E., Fisher, L., Strycker, L. A., Hessler, D., Toobert, D. J., King, D. K., & Jocobs, T. (2014). Minimal intervention needed for change: Definition, use and value for improving health and health research. Translational Behavioural Medicine, 4(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-013-0232-1

Gonçalves, Ó. F., Henriques, M. R., & Machado, P. P. P. (2004). Nurturing nature: cognitive narrative strategies. In L. E. A. J. McLeod (Ed.), The handbook of narrative and psychotherapy: Practice, theory, and research (pp. 102–117). SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412973496.d9

Gonçalves, Ó. F., & Machado, P. P. P. (1999). Cognitive narrative psychotherapy: Research foundations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(10), 1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:103.0.CO;2-L

Gong, L., Li, W., Zhang, D., & Rost, D. H. (2016). Effects of emotion regulation strategies on anxiety during job interviews in Chinese college students. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 29(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2015.1042462

Goodwin, J. T., Goh, J., Verkoeyen, S., & Lithgow, K. (2019). Can students be taught to articulate employability skills? Education + Training, 61(4), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-08-2018-0186

Government of Canada. (2019). Tips on preparing for a job interview. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/interview-entrevue-eng.htm.

Grassi, A., Gaggioli, A., & Riva, G. (2011). New technologies to manage exam anxiety. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 167, 57–62. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-60750-766-6-57

Gunnarsson, A. B., & Björklund, A. (2013). Sustainable enhancement in clients who perceive the Tree Theme Method® as a positive intervention in psychosocial occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60, 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12034

Hamilton, M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32(1), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

Harrison, R. P. (1983). Separate and combined effects of a cognitive map and a symbolic code in the learning of a modeled social skill (job interviewing). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(4), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.30.4.499

Hartung, P. J., Savickas, M., & Walsh, W. B. (2013). Career as story: making the narrative turn. In W. B. Walsh (Ed.), Handbook of vocational psychology: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 33–52). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203143209-9

Hartwell, C. J., Johnson, C. D., & Posthuma, R. A. (2019). Are we asking the right questions? Predictive validity comparison of four structured interview question types. Journal of Business Research, 100, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.026

Heilemann, M. V., Martinez, A., & Soderlund, P. D. (2018). A mental health storytelling intervention using transmedia to engage Latinas: Grounded theory analysis of participants’ perceptions of the story’s main character. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(5), e10028. https://doi.org/10.2196/10028

Hollandsworth, J. G., Jr., Kazelskis, R., Stevens, J., & Dressel, M. E. (1979). Relative contributions of verbal, articulative, and nonverbal communication to employment decisions in the job interview setting. Personnel Psychology, 32(2), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1979.tb02140.x

Hosoda, M., & Stone-Romero, E. (2010). The effects of foreign accents on employment-related decisions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(2), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011019339

Huffcutt, A. I. (2011). An empirical review of the employment interview construct literature. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 19, 62–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2010.00535.x

Huffcutt, A. I., Culbertson, S. S., Goebl, A. P., & Toidze, I. (2017). The influence of cognitive ability on interviewee performance in traditional versus relaxed behaviour description interview formats. European Management Journal, 35(3), 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.07.007

Huffcutt, A. I., Van Iddekinge, C. H., & Roth, P. L. (2011). Understanding applicant behaviour in employment interviews: A theoretical model of interviewee performance. Human Resource Management Review, 21(4), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.05.003

Humm, L. B., Olsen, D., Be, M., Fleming, M., & Smith, M. (2014). Simulated job interview improves skills for adults with serious mental illnesses. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 199, 50–54. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-401-5-50

Jersild, A. T., & Meigs, M. F. (1939). Chapter V: Direct observation as a research method. Review of Educational Research, 9(5), 472–482. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543009005472

Jeske, D., Shultz, K. S., & Owen, S. (2018). Perceived interviewee anxiety and performance in telephone interviews. Evidence-Based HRM, 6(3), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-05-2018-0033

Juan, M. C., & Pérez, D. (2010). Using augmented and virtual reality for the development of acrophobic scenarios. Comparison of the levels of presence and anxiety. Computers & Graphics, 34(6), 756–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2010.08.001

Julian, L. J. (2011). Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale- Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care & Research, 63(Suppl 11), S467–S472. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20561

Kausel, E. E., Culbertson, S. S., & Madrid, H. P. (2016). Overconfidence in personnel selection: When and why unstructured interview information can hurt hiring decisions. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 137, 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.07.005

Kim, S., Larkey, L., Meeker, C., Jo, S., Fonseca, R., Leis, J. F., & Langer, S. (2018). Feasibility and impact of digital stories intervention on psychosocial well-being among patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation: A pilot study. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 24(3), S119–S290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.12.195

Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Kowal, D. S., & Shukla, A. (2021). Correlation of test Anxiety and well-being in an employment interview among job applicants. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychology Research, 4(2), 417–426.

Krajewski, H. T., Goffin, R. D., McCarthy, J. M., Rothstein, M. G., & Johnston, N. (2006). Comparing the validity of structured interviews for managerial-level employees: Should we look to the past or focus on the future? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(3), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905x68790

Kraut, R. E. (1978). Verbal and nonverbal cues in the perception of lying. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(4), 380.

Krishnan, A. I., Mohd Jan, J., & Zainuddin, S. Z. B. (2021). Use of lexical items in job interviews by recent graduates in Malaysia. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 11(4), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-10-2019-0146

Kvale, S. (2007). Introduction to interview research. In Doing interviews (pp. 2–10). SAGE Publications, Ltd, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208963.

Kwon, J. H., Powell, J., & Chalmers, A. (2013). How level of realism influences anxiety in virtual reality environments for a job interview. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 71(10), 978–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.07.003

Labov, W., & Waletzky, J. (1967). Narrative analysis: oral versions of personal experience. Helm, J. (Ed.), Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts. Proceedings of the 1966 Annual Spring Meeting. Distributed by the University of Washington Press (pp. 2–44).

Lapointe, M.-L.B., Blanchette, I., Duclos, M., Langlois, F., Provencher, M. D., & Tremblay, S. (2013). Attentional bias, distractibility and short-term memory in anxiety. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 26(3), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2012.687722

Latham, G. P., Saari, L. M., Pursell, E. D., & Campion, M. A. (1980). The situational interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(4), 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.65.4.422

Lee, J., Lee, E. H., & Moon, S. H. (2019). Systematic review of the measurement properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 by applying updated COSMIN methodology. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(9), 2325–2339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02177-x

Lerner, C. (1979). The magazine picture collage: Its clinical use and validity as an assessment device. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 33(8), 500–504.

Lin-Stephens, S. (2020a). Visual stimuli in narrative-based interventions for adult anxiety: A systematic review. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 33(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1734575

Lin-Stephens, S. (2020b). An image-based narrative intervention to manage interview anxiety and performance. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 26(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrc.2020.1

Lin-Stephens, S., Manuguerra, M., & Bulbert, M. W. (2022a). Seeing is relieving: Effects of serious storytelling with images on interview performance anxiety. Multimedia Tools and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12205-7

Lin-Stephens, S., Manuguerra, M., Tsai, P.-J., & Athanasou, J. A. (2022b). Stories of employability: improving interview narratives with image-supported past-behaviour storytelling training. Education + Training. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-08-2021-0320

Lord, R., Lorimer, R., Babraj, J., & Richardson, A. (2019). The role of mock job interviews in enhancing sport students’ employability skills: An example from the UK. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 25, 100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.04.001

Lugmayr, A., Sutinen, E., Suhonen, J., Sedano, C., Hlavacs, H., & Montero, C. S. (2017). Serious storytelling- a first definition and review. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 76(14), 15707–15733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-016-3865-5

Manuguerra, M. & Heller G. (2020). Ordinal Regression Analysis for Continuous Scales Version 2.02. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ordinalCont/ordinalCont.pdf.

Manuguerra, M., Heller, G. Z., & Ma, J. (2020). Continuous ordinal regression for analysis of visual analogue scales: The R package ordinalCont. Journal of Statistical Software, 96(8), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v096.i08

McCarthy, J., & Goffin, R. (2004). Measuring job interview anxiety: Beyond weak knees and sweaty palms. Personnel Psychology, 57(3), 607–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.00002.x

McCarthy, J. M., & Goffin, R. D. (2005). Selection test anxiety: Exploring tension and fear of failure across the sexes in simulated selection scenarios. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 13(4), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2005.00325.x

McGovern, T. V., Jones, B. W., Warwick, C. L., & Jackson, R. W. (1981). A comparison of job interviewee behaviour on four channels of communication. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(4), 369–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.4.369

McIlveen, P., & Patton, W. (2007). Narrative career counselling: Theory and exemplars of practice. Australian Psychologist, 42(3), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060701405592

McMahon, M., Bimrose, J., Watson, M., & Abkhezr, P. (2020). Integrating storytelling and quantitative career assessment. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(3), 523–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09415-1

McMahon, M., & Watson, M. (2012). Story crafting: Strategies for facilitating narrative career counselling. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 12(3), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-012-9228-5

McNamara, P., Moore, K. H., Papelis, Y., Diallo, S., & Wildman, W. J. (2018). Virtual reality-enabled treatment of nightmares. Dreaming, 28(3), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/drm0000088

Melchers, K. G., Petrig, A., Basch, J. M., & Sauer, J. (2021). A comparison of conventional and technology-mediated Selection interviews with regards to interviewees’ performance, perceptions, strain, and anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 603632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.603632

Michopoulos, I., Douzenis, A., Kalkavoura, C., Christodoulou, C., Michalopoulou, P., Kalemi, G., Fineti, K., Patapis, P., Protopapas, K., & Lykouras, L. (2008). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Annals of General Psychiatry, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859x-7-4

Morina, N., Brinkman, W., Hartanto, D., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2014). Sense of presence and anxiety during virtual social interactions between a human and virtual human. PeerJ, 2, e337–e337. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.337

Nguyen, L. S., Frauendorfer, D., Mast, M. S., & Gatica-Perez, D. (2014). Hire me: Computational inference of hirability in employment interviews based on nonverbal behaviour. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 16(4), 1018–1031. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2014.2307169

Nguyen, T. T. T., Bellehumeur, C., & Malette, J. (2018). Images of God and the imaginary in the face of loss: A quantitative research on Vietnamese immigrants living in Canada. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 21(5), 484–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2018.1499715

Peeters, H., & Lievens, F. (2006). Verbal and nonverbal impression management tactics in behaviour description and situational interviews. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 14(3), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00348.x

Peterson, M. S. (1997). Personnel interviewers’ perceptions of the importance and adequacy of applicants’ communication skills. Communication Education, 46(4), 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529709379102

Polman, E., & Emich, K. J. (2011). Decisions for others are more creative than decisions for the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(4), 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211398362

Powell, D., Bourdage, J., & Bonaccio, S. (2020). Shake and fake: The role of interview anxiety in deceptive impression management. Journal of Business and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09708-1

Powell, D. M., Stanley, D. J., & Brown, K. N. (2018). Meta-analysis of the relation between interview anxiety and interview performance. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 50(4), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000108

Proost, K., Derous, E., Schreurs, B., Hagtvet, K. A., & De Witte, K. (2008). Selection test anxiety: Investigating applicants’ self- vs other-referenced anxiety in a real selection setting. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 16, 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2008.00405.x

Pronin, E. (2008). How we see ourselves and how we see others. Science, 320(5880), 1177–1180. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1154199

R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Roberts, C. (2012). Translating global experience into global models of competency: Linguistic inequalities in the Job Interview. Diversities, 14(2), 49–72.

Ross, L., & Moffatt, N. (2018). Preparing for the real thing with practice interviews: A graduate paramedic perspective. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 15(2), 567. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.15.2.567

Russell, B., Perkins, J., & Grinnell, H. (2008). Interviewees’ overuse of the word “like” and hesitations: Effects in simulated hiring decisions. Psychological Reports, 102(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.102.1.111-118

Sackett, P. R., Burris, L. R., & Ryan, A. M. (1989). Coaching and practice effects in personnel selection. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology 1989 (pp. 145–183). Wiley.

Santilli, S., Di Maggio, I., Ginevra, M. C., Nota, L., & Soresi, S. (2021). Stories of courage in a group of asylum seekers for an inclusive and sustainable future. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09495-y

Savickas, M. (2015). Life-design Counseling Manual. Retrieved from http://www.vocopher.com/LifeDesign/LifeDesign.pdf.

Schacter, D. L., & Addis, D. R. (2007). On the constructive episodic simulation of past and future events. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(3), 331–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07002178

Schneider, L., Powell, D. M., & Bonaccio, S. (2019). Does interview anxiety predict job performance and does it influence the predictive validity of interviews? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 27(4), 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12263

Sieverding, M. (2009). “Be Cool!”: Emotional costs of hiding feelings in a job interview. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17(4), 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2009.00481.x

Snaith, R. P. (2003). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-29

Spielberger, C. D. (1985). Anxiety, cognition and affect: a state-trait perspective. In A. H. Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders (pp. 171–182). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. C. (2007). The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07001975

Sydiaha, D. (1962). Interviewer consistency in the use of empathic models in personnel selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 46(5), 344–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046526

Thomas, M., & Tsai, C. I. (2012). Psychological distance and subjective experience: How distancing reduces the feeling of difficulty. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(2), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1086/663772

Thompson, R. H., & Borrero, J. C. (2011). Direct observation. In W. W. Fisher, C. C. Piazza, & H. S. Roane (Eds.), Handbook of applied behaviour analysis (pp. 191–205). The Guilford Press.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2012). Construal level theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 118–134). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Tross, S. A., & Maurer, T. J. (2008). The effect of coaching interviewees on subsequent interview performance in structured experience-based interviews. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(4), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X248653

U.K. Government. (2016). A brief guide to competencies. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/a-brief-guide-to-competencies.

U.S. Department of Labor. (2019). Employment Fundamentals of Career Transition: Participant Guide. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/VETS/files/EFCT-Participant-Guide.pdf.

Van Boven, L., Kane, J., McGraw, A. P., & Dale, J. (2010). Feeling close: Emotional intensity reduces perceived psychological distance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 872–885. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019262

Weierich, M. R., Treat, T. A., & Hollingworth, A. (2008). Theories and measurement of visual attentional processing in anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 22(6), 985–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701597601

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton.

Williams, K. Z. (2008). Effects of Practice and Feedback on Interview Performance. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Williams, K. Z. (2012). Does Practice Make Perfect? Effects of Practice and Coaching on Interview Performance (Publication Number 3525932) [Ph.D., Clemson University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Yan, J., Hou, S., & Unger, A. (2014). High construal level reduces overoptimistic performance prediction. Social Behavior and Personality, 42(8), 1303–1314. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.8.1303

Zielinska, A. P., Mawhinney, J. A., Grundmann, N., Bratsos, S., Ho, J. S. Y., & Khajuria, A. (2021). Virtual interview, real anxiety: Prospective evaluation of a focused teaching programme on confidence levels among medical students applying for academic clinical posts. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 12, 675–683. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S306394

Zigmond, A. S., & Smaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Ziller, R. C. (2000). Self-counselling through re-authored photo-self-narratives. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 13(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/095150700300091884

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the thorough reviews by Associate Professor James Athanasou at the University of Sydney, the anonymous reviewers, and the editors. We also sincerely thank Professor Sherman Young at RMIT University and Associate Professor James Downes at Macquarie University for their support of this research.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its member institutions. No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin-Stephens, S., Manuguerra, M. Using visual stimuli in narrative career interventions: effects of image-supported storytelling on interview anxiety and performance. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-023-09603-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-023-09603-0