Abstract

Accusations of dishonourable campaigning have featured in every Argentine presidential election since the return to democracy in 1983. Yet, allegations made in the elections this October and November looked different from earlier ones. The campaign team for the centre-leftist candidate Daniel Scioli argued that Cambiemos, the centre-right coalition led by Mauricio Macri, was abusing the political affordances of social media by running a Twitter campaign via ‘50,000’ fake accounts. This paper presents evidence suggesting that both teams promoted their campaigns through automation on Twitter. Although the Macri campaign was subtler, both teams appear to have used automation to the same end: maximizing the diffusion of party content and creating an inflated image of their popularity. Neither team attempted to muffle or engage with opposing voices through automation. We argue that in a political culture fixated on the appearance of popularity, the use of automation to simulate mass support appears an organic development as campaigning enters the still unregulated Twittersphere. We compare our findings to the uses of automation in the Russian Twittersphere and conclude that there may be greater variation in the political usage of Twitter between political contexts than between different types of political event occurring in the same country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At the height of the campaign season for the Argentine presidential elections in October 2015, the leftist Frente para la Victoria (FpV), currently led by President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, accused its main opposition, the centre-rightist Cambiemos coalition, of conducting a ‘dirty campaign’ (FpV detalló la denuncia 2015).Footnote 1 The accusation took place against the backdrop of severe flooding in the Province of Buenos Aires, during which three died and 11,000 were evacuated. The Mayor of the City of Buenos Aires and Cambiemos candidate Mauricio Macri admonished Daniel Scioli, Governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, for mismanaging the disaster. In turn, the FpV decried Cambiemos for its ostensibly ‘dirty and negative’ campaign tactics. Such accusations of dishonourable campaigning are commonplace in Argentine electoral politics, having featured in the run-up to every presidential election since the transition to democracy in 1983. The complaint, like those prior ones, drew on the language of democratic rights and duties to describe the Cambiemos campaign as an affront to ‘transparency’ and an abuse of ‘freedom’ (FpV detalló la denuncia 2015). This time, however, the claim had an important distinguishing feature. The FpV alleged, in an awkwardly phrased communication, that Cambiemos abused the political affordances of social media, running a Twitter campaign via ‘50,000’ accounts that ‘aren’t real, that are automated and managed by computer programmes, or accounts with false numbers and letters attached to them, that seek to tarnish the [social] networks with false information’ (FpV detalló la denuncia contra Cambiemos 2015). More than just the story of lies and cover-ups that previous campaigns drew upon, this allegation centred on the medium of deception and the scale of subterfuge that it made possible.

This paper studies automation and the accusations that surrounded it in the 2015 Argentine presidential elections, observing apparent perceptions of the relationship between elections, democracy, and digital technologies among the two principal campaign teams. We present evidence suggesting that both teams and their supporters drew on automated or partly automated accounts to promote their campaigns on Twitter. Given that effective organized campaigns simulate grassroots support, it can be difficult to distinguish between the two. Below, we discuss, on the one hand, automation that coincides with campaign events and looks to be centrally coordinated. On the other, we look at the usage associated with individual accounts at less critical junctures, which points towards disaggregated activity. The nature of the subject is such that there will always be a degree of plausible deniability. Three types of automation may be useful to electoral campaigning: pushing messages on a mass scale, faking grassroots support, and playing dirty tricks (by smearing the opposing candidate or controlling the space by flooding content). In these elections, we find the first two types to be more prevalent than the last. Both the Scioli and Macri campaigns appear to have used automation principally for amplification—maximizing the diffusion of party content—rather than to muffle the other side. Automated content associated with the FpV campaign went into overdrive in the week preceding the first round vote. It went into hibernation immediately after, before picking up again a week before the second round. This pattern of activity suggests that, though academic studies have struggled to pinpoint a link between online campaigning and offline voting patterns, the FpV drew a direct relationship between the two.

Despite the broad access to and intensive usage of digital technology and social media in Argentina, scant scholarly literature analyses how Argentines use social media or even the Internet more broadly. The available literature predominantly examines domestic online journalism or online interactions between media and the state. Argentina is not alone in the limited attention afforded to the political uses of online spaces. As Sebastian Valenzuela (2013, p.2) notes, ‘most data on social media and protest behaviour have been collected in either mature democracies or authoritarian regimes’, with little attention afforded to ‘the special case of third wave democracies’—states that democratized between the 1970s and 1990s. Literature examining Argentine online electoral campaigning is almost non-existent (Senmartin 2014). This paper begins to address the deficit. It focuses on automated activity used to support one or the other of the two parties represented in the runoff on 22 November 2015. We seek to understand both how the two campaigns used automation and what relationship these activities suggest Argentine campaign strategists and politicians perceive between online campaigning and offline electoral participation.

Politics and Social Media in Argentina

Argentina entered election season in an already tense political climate. Perceived economic mismanagement coupled with controversy surrounding the death of special prosecutor Alberto Nisman in January 2015 plagued the FpV. Still, the levels of confidence in Fernández remained buoyant (de los Reyes 2015). Exit polls for the first round vote on 25 October 2015 predicted a victory for her chosen Peronist successor, Daniel Scioli (Watts 2015). To win the election in the first round, a candidate must earn either 45 % of the vote or 40 % with a 10-point lead on the closest candidate (Watts 2015). Scioli took 36.7 % of the vote, closely followed by Mauricio Macri who gained 34.5 %. The impasse led to the first presidential runoff in Argentine history, leaving the candidates with everything to fight for.Footnote 2 Would the five million votes that Sergio Massa won on 25 October, ranking him third, go to Scioli or to Macri? Massa had formed a non-FpV Peronist coalition, the Frente Renovador (Renewal Front), which seemingly offered a middle ground between the Kirchnerists and Cambiemos. This positioning made it hard to predict which way his supporters would vote on 22 November.

Social media served as contentious electoral terrain in both rounds, but online campaigning accelerated in the days before the runoff, with much of this increased activity attributable to the campaigns embracing the affordances of automation. Politicians have a reason to view social media as a key battleground. Argentines spend more hours per day on social media than any other nationality (Social media: daily usage in selected countries 2014). Roughly 4.8 million Argentines, or just over 10 % of the population, visit Twitter every month. Although Twitter attracts a broad age range, its key market in Argentina, as elsewhere, is 18–29 (Schoonderwoerd, 2013). The attention that Argentine politicians pay to social media suggests that they recognize the widespread use of these online platforms in Argentina, particularly among the youngest segment of the newly expanded electorate. Their online activity indicates that they perceive Twitter to provide a forum for shaping the political opinions of first-time and young voters.

Courting the youth vote has long formed part of Kirchnerist strategy. In 2012, the Congress approved Fernández’s bill to lower the voting age from 18 to 16. When passed, the law enlarged the electorate by one million (Argentina Voting Age 2012). At the same time, the FpV invested in enhancing the strength and capacities of La Cámpora, the Kirchnerist youth organization led by Máximo Kirchner, the son of Fernández and former president (2003–2007) Néstor Kirchner. La Cámpora and President Fernández, along with other politicians and political parties, embraced social media platforms for political messaging. Fernández famously stopped giving press conferences when president. She framed the media—with whom her relations were fraught—as an untrustworthy intermediary between her and the people. Harnessing the immediacy of social media thus enabled Fernández to update for the twenty-first century the projected image of being in ‘direct contact with the people’, a performance that populist governance demands and that Peronism, in its various iterations, has long perfected (Plotkin 2002, p. 82). Fernández maintained an active presence on Twitter and Facebook and regularly posted blogs on her presidential website, cfkargentina.com (Garrido 2012, p. 124). A number of Twitter mishaps suggest that the president, at least some of the time, personally operated this account (see e.g. Rueda 2012). It is likely that any opposition candidate seeking to make incursions into the typically Peronist voter bases would have needed to engage in at least some comparable social media strategies.

The Scioli campaign keenly channelled the mobilizing potential of the Internet, notably through its ‘Ola Naranja’ (‘Orange Wave’) platform which encouraged ‘digital activism’. Users could download content to disseminate across social media and instructions for effective social media usage, which were reportedly also offered via online ‘Hangouts’ and live training sessions. According to Perfil, a newspaper known for anti-Kirchnerist reportage, 100 digital advisors were leading Scioli’s online campaign and www.olanaranja.com had 10,000 subscribers or ‘cyberactivists’ by June (Ayerdi 2015). The Macri campaign had a communications team led by the Ecuadorian political consultant Jaime Durán Barba, who has worked on several presidential campaigns across Latin American. The team also included Argentine political communications professionals, including former journalists at Clarín and La Nación. In late 2014, young staffers were reportedly already working from the campaign headquarters to implement the team’s digital strategy (Sirvén 2014). Digital mobilization via automated activity appeared to feature more heavily in the Scioli campaign overall, but in the final days before the runoff, as we will see, both campaigns urged their followers to engage in online ‘activism’. By the end of the campaign, http://mauriciomacri.com.ar also offered downloadable photographs for distribution on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp.

It is worth underlining the improbability of Macri or Scioli having in-depth knowledge of social media campaign strategizing in general or bot usage and its technical complexities in particular. More probable is that campaign strategists on their respective teams brought in third-party social media consultants, who led them down the automated path. We cannot, then, assign direct agency to the leaders for specific acts likely put in place by their campaign team. Yet, voters often understand the overall responsibility for transparent campaigning ultimately to lie with the candidates.

The idea of thousands of automated Twitter accounts polluting the online discussion may sound farfetched, but it is a reality in certain parts of the world, notably Russia. In 2012, one Russian botmaster was jailed; his ‘botnet’ had consisted of 30 million hijacked computers, which produced 3 billion spam emails every day. As of 2012, 36 % of cyber-crimes were committed by ‘Russian-speaking hackers’. Not for nothing did security blogger Brian Krebs call Russia ‘Spam nation’ (Krebs, 2014). At the time of the 2011 and 2012 elections in Russia, the BBC and other outlets reported on organized campaigns to undermine hashtags used by opposition activists to organize protest marches (Russian Twitter political protests 2012). A stream of automatically generated tweets drowned out authentic messages. The purpose, apparently, was to prevent the Russian opposition exploiting the mobilizing potential of Twitter (Paulsen and Zvereva 2014).

This level of automation is facilitated by a booming spam-as-service sector. Automation services for Twitter are marketed from all dark corners of the internet. However, the diversity of Russian sites is staggering: forumok.com, twite.ru, twitterstock.ru, prospero.ru, socialtools.ru, soclike.ru, rotapost.ru, and blogun.ru help users to monetize their microblogs. Forumok.com is a marketplace where users bid to place tweets; Twitterstock is dedicated to buying and selling accounts; Prospero offers a plugin to automate posting; and users on Socialtools and Soclike are paid to ‘execute tasks on Twitter’. In Argentina, however, it is noticeable how many of the services used, e.g. botize.com, are Spanish language; there is relatively little surface-level cross-language activity, though there may be overlap in implementation behind the scenes; accounts may be marketed on multiple sites, run in different languages. Some products are probably homegrown, reflecting the strength of Argentine offerings. Argentine hackers and network engineers, typically self-taught, are widely regarded as some of the most talented and creative globally (on Argentine hackers see Perlroth 2015).

Methods

We identified a series of hashtags used by political actors as part of their election campaigns. Of these, we selected the most popular hashtags for closer scrutiny: the Scioli campaign mobilized around the #ScioliPresidente hashtag and the Macri campaign primarily the #Cambiemos hashtag, before moving to #MejorScioli and #MacriPresidente and #Yo Cambio respectively at the close of the campaigns. On the morning of 27 October 2015, the day after the first round of voting, we began the collection. The Twitter Search API gives access to tweets posted during the last 7 days (Twitter Developers 2015). Upon its first iteration, ourscript collected all available content. Subsequent iterations took place every 15 min, searching for any new content. This collection process means some content posted in the first hours after each event will have been deleted before collection, meaning there may be a slight bias in the data for the period 20–27 October. Selecting tweets by hashtags returns a relatively thin slice of the relevant material; it prioritizes tweets aimed at a wide audience but misses conversations and messages aimed directly at a follower-base. In a study of online mobilization, this approach is appropriate, but it is worth bearing in mind that our view of the data is partial and imperfect, and the observations below should be treated as such.Footnote 3

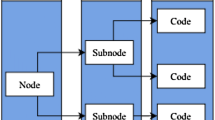

There are three main types of automated activity on Twitter: first, some accounts are created, populated, and/or operated automatically; second, automation can be used to boost online social capital; and third, automation can help extend message reach. In many cases, scripts are used to register accounts, populate them with a number of followers, a profile picture, and a user description. Scripts can also be deployed to populate a newsfeed, with a cocktail of user-generated and retweeted content. Once populated, such accounts can be monetized, e.g. by renting them out. When studying automation on Russian Twitter, we found many accounts that were clearly automatically created but that appeared to be manually curated, possibly by one of the various troll-farms (Chen, 2015). Automation can also be used to simulate and to grow an online presence. Famously, at one point during the Romney campaign, media reports suggested most of his new followers had been provided by a Twitter-follower service (Kerr, 2012). Automation can also boost exposure, e.g. by using a series of accounts to automatically retweet and favourite everything a user posts; this helps to create the impression of user engagement and to game metrics. Finally, numerous organizations and media outlets use automation to time Twitter campaigns, e.g. by periodically re-posting a message to maximize its exposure.

Dividing accounts into ‘bot-like’ and ‘real’ users is thus a fraught process, not only because it inevitably will result in a significant number of both false positives and false negatives but also because some ‘real’ accounts may periodically use automation, while humans can operate automatically created accounts. For this reason, we talk about ‘bot-like’ accounts, by which we mean accounts whose activity looks like it could be automated, that is, performed either by a script or a person doing copy-paste operations.

In identifying bot-like accounts, we targeted the two most blatant forms of automation: automatic creation of accounts and the use of multiple accounts to promote a single message. We looked for non-random clustering of user creation dates to identify periods when accounts may have been created en masse. To identify whether spikes are anomalous, we used Twitter’s own anomaly detection algorithm (Kejariwal 2015).Footnote 4 We identified duplicated content, i.e. substantively identical tweets that are not retweets and also not posted automatically through a news outlet’s Twitter widget. Heavily duplicated messages, posted by accounts where the majority were created in the same month, were labelled as possibly automated. Accounts where the majority of tweets had been identified as possibly automated were labelled as bot-like. Additionally, we identified a cluster of bots based on patterns in usernames, a number of accounts that never tweeted anything except hashtags and links, and accounts that tweeted from rare third-party sites, e.g. botize.com, as likely automated.

Results

Figure 1 shows anomalous clusters in creation dates. The plot reveals a period of anomalous activity in 2010. Inspecting these accounts, we found a large number of political activists who in 2015 tweeted about #Cambiemos and #ScioliPresidente. Turning to the more recent, dramatic spikes in account creation, we find unusual activity on both hashtags. In the case of #Cambiemos, a cluster of bots was created in the period 18–20 August 2015, around the time when the FpV accused Cambiemos of using automation, while a cluster of bot accounts active on #ScioliPresidente was created a few weeks earlier, in the period 28–30 July 2015. Most pro-Scioli bots, though, were created in the period between the first and second round. We manually verified that a large number of these accounts were populated automatically. In both cases, they follow a template where occasional political content is surrounded by apolitical material—in particular news stories about and pictures of Argentine soccer superstars such as Lionel Messi and Sergio Agüero. Tellingly, the accounts tended to post identical content, making the verification process simple. The proportion of accounts created during anomalous spikes is higher for the pro-Scioli hashtags. The large spike towards the end was mainly comprised of users that proceeded to create authentic-looking content, which leads to two possible readings: either numerous Scioli supporters joined Twitter at the time of the presidential debate held on 15 November or a large cluster of automatically created accounts were manually curated.

Turning to message content, we found that just under 25 % of users were bot-like: of accounts active on #ScioliPresidente, 22 % are likely bot accounts, compared to about 15 % of users on #Cambiemos. Our two approaches to bot identification reveal that both candidates’ campaigns are associated with an element of automation. However, the bots are put to markedly different uses: Fig. 2 contrasts the number of tweets created by accounts identified as bot-like or real. At first glance, it appears to show that #Cambiemos was largely bot-free.Footnote 5 The volume of tweets reflects a daily rhythm, with less content being created at nighttime. #ScioliPresidente, though, has seen a remarkably unsubtle automation campaign, as evidenced by an artificially even level of bot-generated output in the week running up to the first round of voting. Then, on October 25, these accounts fell silent.

While the number of bot-like users is similar, the proportion of automated content on #Cambiemos is 15.7 %, compared to 43 % for #ScioliPresidente. Given this disparity, we focus in the following analysis on pro-Scioli accounts, before returning to consider pro-Macri activity.

The online campaigns were most intense around the time of five electoral milestones: the official end of campaigning before the first round of voting, on 22 October, the first round on 25 October, the presidential debate on 15 November, the end of campaigning before the second round on 19 November, and the second round on 22 November. Each of these junctions is associated with distinct types of automated activity on pro-Scioli hashtags.

During the period 19–25 October, a small number of hyper-active accounts promulgated the official Scioli campaign’s message as widely as possible. The effect is an almost horizontal line in Fig. 2. The output was constant, at all times of day. A relatively small number of bot accounts, bearing names such as SCIOLI2015, tweeted thousands of largely identical Tweets, often together with pictures of Scioli campaign posters. These accounts, which also retweeted everything posted by Scioli’s official account, were operated through an automation service, botize.com, registered in Valencia, Spain. As a result, every single message tweeted by Scioli—and he tweets a lot—has been retweeted hundreds of times.

On November 15, a shift occurred in the bot-like activity associated with #ScioliPresidente, from a high volume of Tweets from a few accounts to low volume from many accounts. This shift aligns with the largest spike in mass account creation shown in Fig. 1. This content can largely, if not easily, be identified as automated.Footnote 6 The low volume approach is more sophisticated and more costly (in terms of time, money, or both). The seeming willingness to increase social media investment suggests a sense of urgency in the FpV camp, hours before a presidential debate that, by many accounts, Scioli failed to dominate (Debate Presidencial 2015). As the debate occurred a week before the ballot, this attempt at debate-specific image management may have blended into a more general last push for votes. Overall, however, Scioli’s social media campaign targeted the debate far more than it did either round of voting. The campaigns officially closed at 6 pm on 19 November, at which point both candidates directed supporters on Facebook, Twitter, and their respective websites to use specific hashtags. Macri asked followers to use #MacriPresidente and #YoCambio; Scioli directed his supporters to use #MejorScioli. At 6 pm, 37,600 tweets from 18,000 accounts included #YoCambio, decreasing to 25,000 by 7 pm and quickly tailing off after that. Fifty six thousand five hundred tweets from 12,000 accounts used #MejorScioli, which remained buoyant an hour later, attracting 53,000 tweets at 7 pm. Activity on #MejorScioli also died down rapidly after 7 pm.

The move to #MejorScioli was foreshadowed by automated activity on the hashtag on 15 November and again on 18 November. In both cases, a handful of accounts tweeted identical content. During this time, multiple accounts tweeting identical material were operated through various third-party social media management systems: in the first instance, Hootsuite was used. ‘Tweetdeck’ was preferred a few days later. After the end of the campaign, there was a move to yet other platforms, specifically grabinbox.com (on 22 November) and ifttt.com. Material tweeted through ifttt mirrored activity through botize prior to the first round of voting. Many of the new accounts created in the week 13—19 November tweeted to the #MejorScioli hashtag, including after 8 am on 20 November, when the prohibition on campaigning began (see Appendix).

Overall, the absence of smear campaigns and attempts at hashtag-capture on either side is striking: little negative content was posted to hashtags that made reference to the competing candidate. The negative content we did find was primarily created by Macri supporters who tweeted at otherwise pro-Scioli hashtags. There were no noticeable spam-for-profit campaigns piggy-backing on the political campaign hashtags. Likewise, there was no attempt to undermine the mobilizing potential of hashtags through torrents of irrelevant material. Typically defamatory phrases used offline and turned into hashtags for the Twitter environment—#MacriCagon (‘#MacriIsTrash’) and #ScioliCagon (‘#ScioliIsTrash’), for example, had little (<5 %) automation associated with them. Contrastingly, ‘real’ users actively included the disparaging hashtags in their Tweets, hinting that smearing was overwhelming a form of ‘authentic’ online activity.

Discussions/Conclusions

Both online campaigns looked choreographed to perform a specific function: to produce the appearance of popularity. Automation enables campaigns to game metrics, an urgent task in the poll-obsessed world of contemporary politics. The media increasingly seek to integrate statistics into their analyses to lend credence to their predictions, with quantitative data fetishized more than ever in the 2015 electoral campaign coverage. One of the unlikely celebrities of the elections, as The New York Times reported, was a hobbyist statistician who produced data visualizations to analyse the elections as they unfolded, which he posted on his blog (Gilbert 2015). La nación, internationally renowned for its creative integration of data and data visualizations into its reportage, repeatedly used the social media analysis company Flowics to monitor campaign action and support on Twitter and Facebook.

The move to new hashtags by both campaign teams, with followers provided with a timeframe for activity on them, suggests some minimal awareness of how to game the twitter trending topics algorithm. The algorithm captures change in intensity rather than high volume. Soon after the campaign season officially closed, La nación announced in an online article that Macri had ‘won’ on Twitter; #YoCambio had emerged as the primary trending hashtag, with #MejorScioli apparently trailing in third place. The statement echoed the result published across media after the second presidential debate (see, for example, Las encuestas de los medios 2015 and Macri arrasó en todas las encuestas de Twitter sobre el #ArgentinaDebate 2015). This kind of traction seems to have been the ultimate ambition of both campaigns. It suggests the extent to which they both imagined voters to conform to a herd mentality, by which logic to become popular the candidates needed first to appear popular, with the statistics to confirm that image.

If this particular ambition unified the two campaigns, differences also abounded in their approaches and the online images that they ultimately projected. One distinction lies in the level of centralized coordination and professionalization that appear to have shaped the two campaign strategies. In his work on the organizational structures behind the 2012 Mitt Romney and Barack Obama presidential campaigns, Daniel Kreiss (2014, pp. 3–11) outlines their respective approaches to social media, particularly Twitter. Although the structures and functionalities of the social media teams in the Republican and Democratic campaigns differed from one another, Kreiss describes both as highly professionalized and integrated into the overall campaigns. The social media effort around the presidential debates in the Romney campaign was pre-planned and meticulously choreographed. The Obama social media campaign, contrastingly, was more flexible. Social media staff had a clear collective vision that enabled individuals to work autonomously and spontaneously. We do not have access to the internal workings of either party’s social media strategy in Argentina, but the image that our data concerning automation provides suggests differences in the Argentine parties from both of the US campaigns.

Particularly in the Scioli Twitter campaign, professionalization appears lacking. The campaign began slowly. Then, it careened towards bulk account creation. This approach can provide no artifice of organicity; automation or at least coordinated account creation is a statistical certainty. Most bots were deployed almost immediately after their creation, with little effort going into populating them with followers, a backstory, or a credible-looking timeline. Blending in with real accounts was not always a priority. Deployed in bursts, this style of automation manifests little attempt to control or influence the online space beyond certain critical junctures. To be sure, as both US campaign teams were aware, timing can be key (Jungherr, 2014). Critical moments, such as a debate, can be planned for: the appearance of instantaneity or spontaneity requires neither instantaneous production nor spontaneous performance. Yet, the pro-Scioli material feels improvised. Occasional spikes in output were produced by individual accounts, likely operated through homemade scripts that tweet in large quantities. The sudden and sizeable ramp-up that characterized the second burst of automation suggests campaign staff learned on the job and perhaps indicates confusion surrounding best strategy. It is at least ironic that Carlos Gianella, technical director to Scioli, described the fake Twitters accounts that he attributed to the Cambiemos campaign as a sign of Macri’s ‘desperation’ (El Sciolista que denuncia 2015).

The activity surrounding the pro-Macri hashtags hints that more experienced hands were at work. The campaign was subtler and seemingly more professionalized. Both teams used automation to promulgate their message as widely as possible, but in Scioli’s case, verbatim copies of messages were pushed directly by supportive accounts. Both campaigns employed retweet bots, an approach that uses third-party bots for hire to increase the reach and visibility of material with relative subtlety. Like Scioli and his Ola Naranja, Cambiemos also apparently sought to blur the line between automation and activist. They equipped supporters with the tools for the decentralized implementation of automation, for instance by operating multiple accounts and the provision of downloadable images. As a result, the Macri campaign blended automation—centralized or produced by independent activists—with genuine grassroots activity and transparent official campaigning. If inconspicuous integration was the ambition, it was successfully met.

The question of expertise extends beyond campaign teams and their advisors alone. By the end of the runoff, Jorge Di Lello, the electoral prosecutor, had received 63 complaints, of which 52 lambasted President Fernández, for apparent continuities in electioneering after the embargo on campaigning began on 20 November (El fiscal recibió 53 denuncias contra Cristina por violar la veda electoral 2015). Di Lello announced that, among his investigations, he would analyze the President’s tweets to check if they violated the prohibition on campaigning. Such an approach appears superficial. It risks missing the main, and subtler, event—the use of automation after close of play. It is not only campaigning practitioners who must learn the art of online persuasion and manipulation, then, but the watchdogs too. Since the 1990s, the field of transparency and anti-corruption has consolidated and professionalized in Argentina, gaining public prominence and respect. As social media enables new forms of subversion, that field will need to adapt accordingly. Begun as a project by leading Argentine legal minds, our data suggests that it will need to acquire a new technical dimension: the watchdog can no longer only be a constitutional expert but must also be a network specialist, equipped to reveal covert structural manipulations online. The public attention that cyber activism has generated in Argentina hints at a recognition that Twitter is unregulated space and the mechanisms and knowledge to control it not yet fully established.

Our findings do not, of course, tell the full story about Argentine electoral campaigning on Twitter. For a start, though we find little evidence of negative campaigning via automation, it may have occurred through other, subtler, means. Smearing does not require automation: people, not just bots, love sensational news. What is clear, however, is that little Russian-style hashtag-capture took place. There has been no attempt to shut down spaces of information and opinion through streams of spam or irrelevant content. By and large, ‘spam-like’ material has been directed at candidates’ own information space. It is important to emphasize that our data form only a small portion of the Twitter commentary on the elections. Because the lens through which we approach the question of automation centres on hashtags, our focus has been on the areas to which the campaigns dedicated most attention. Popular hashtags will have acted as magnets for automated activity, certainly from spam marketers, but also likely from other bots that ‘piggy-back’ on trending subjects. The same levels of automation are unlikely to be observed in the ‘conversation’ at large. Limitations in our dataset mean we are unable to measure quantitatively the degree to which automated content in political campaigns is restricted to hashtags. More work in this area is need.

The online behaviours that we find here suggest that the elections have not triggered political communications strategies on Twitter that veer significantly from those surrounding other Argentine political events. In 2012, Kreiss identified how little we know about the ways in which campaign strategists and political elites ‘seek to channel, steer, influence, respond to, or otherwise manage networked political communication on social media platforms’ (Kreiss, p. 2). Our research suggests that this may differ at least as much from one political context to another as from one type of political event to another. During the 2011 Russian presidential elections, extensive hashtag flooding drowned out opposition voices (Elder, 2011). In a comparative analysis of political discourse on Twitter following the death of Alberto Nisman in Argentina and the murder of Boris Nemtsov in Russia, we detected similar behaviour on the Russian Twittersphere in the aftermath of Nemtsov’s death (Filer and Fredheim, 2016). In Russia, automation was used to hijack hashtags associated with the opposition, flooding them with spam to such an extent that it became almost impossible to stumble across real oppositional content. Bot clusters also tweeted at other bots, tweeted en masse ‘at’ individuals who wrote about #Nemtsov and specialized in retweeting high-profile bloggers. Automation undermined the potential of hashtags to expose individuals to oppositional material.

Following the death of Nisman, the emphasis in the Argentine Twittersphere was on amplification rather than drowning out opposing voices. Little use of automation was detected (Filer and Fredheim 2016). Twitter activity during the elections looked consistent among both camps with this ambition to promote messages and perhaps mobilize offline support, rather than to shut down alternative opinions. The principal novelty during the elections was methodological: the use of automation for amplification. The two teams seemed to perceive amplification on Twitter as a worthwhile investment, albeit only in bursts around key events rather than via the protracted automation seen in Russia. This turn to automation both changed the scale of political discourse on Twitter and created less of a genuine conversation. There were fewer uniquely worded messages, with retweets and duplicated messages—the result of automation or manual copy and pasting—dominating the space. Endless replication during the elections replaced the more authentic feel of the Twitter discourse around #Nisman. Taking two crude indicators of automation, proportion of duplicated content and proportion of accounts that tweeted about the hashtags within 10 days of account creation, the leap in levels of automation is clear. Automation on #Cambiemos was at least twice that on #Nisman, while for #ScioliPresidente and #MejorScioli we found between 8 and 10 times as much automation. The increase in scale and the reduction in polyvocal activity on Twitter do not alter the status of amplification as the end goal of political commentary on the Argentine Twittersphere. Read together with analysis of the Twittersphere following the Nisman affair, our findings suggest that political events beget social media responses that reflect the political environment in which they occur more than the type of event itself. Further research would do well to foreground the role of the domestic political ecosystem in determining the types of national discourses and strategies played out in the ‘global’ Twittersphere.

Attentiveness to national politics may also help to understand the role that accusations of automation played in these elections. If allegations of dirty campaigning have long abounded in Argentine electoral campaigning, why did the FpV focus now on automation? To have traction, the accusation required introducing the public to a new vocabulary—‘bots’, ‘automated content’, ‘botnets’—that required explanation. This complexity risked distracting from the straightforward and well-rehearsed task of painting the opposition as untrustworthy. One explanation is that the FpV’s claim was true, in outline if not in detail. The focus perhaps also diverted attention from Macri’s admonishment of negative campaigning by the Scioli camp, which included a televised advertisement comparing PRO economic policy to that of the military authoritarians of the 1970s and 1980s and another asking the viewer to ‘imagine the hunger’ that Macri’s presidency would beget (Argentina: Macri acusa 2015).

Twitter’s global reach and popularity may offer a further explanation of why the FpV highlighted how the medium could be used to deceive. Peronists have long observed disparagingly that opposing candidates hire and learn from foreign campaign strategists. The accusation serves as shorthand for selling the nation out, an omen of what the national future would hold should their opposition win (e.g. see Menem 1989, p.35). In the 2015 campaign, FpV supporters noted how Macri’s campaign team embraced strategies previously used abroad (Girondo 2015). By focusing on automation, the FpV did not so much depart from Peronist tradition as shape its latest iteration.

In the same way as accusations of unfair play pre-date the social media age, the practice of producing inflated images of popular support has long pervaded Argentine political life. Offline, examples and accusations of Argentine politicians and parties magnifying the appearance of their popularity are commonplace. These tendencies should perhaps be expected in a country that fuses electoral democracy and populist leadership. Populism frames the leader as the ultimate expression of the will of the people; the image of mass support is therefore intrinsic to the appearance of legitimate rule or serious opposition. Denunciations claiming crowds are ‘bussed in’ to inflate the image of popular support regularly accompany protests and rallies.Footnote 7 The limited use of automation surrounding the Nisman case is perhaps the bigger surprise than its presence within the electoral context. In a political culture fixated on the appearance of popularity, the use of automation to simulate mass support appears an organic development. So too does the attempt by opposing parties to deflate that image. They are part and parcel of introducing digital technologies to Argentine political culture.

Notes

Mauricio Macri’s Propuesta Republicana (PRO) party formed the Cambiemos coalition along with members of the Union Civil Radical party and the Coalición Cívica.

The election went to a runoff in 2003, but Carlos Menem retracted his candidacy before it took place, in effect handing presidential office to Néstor Kirchner.

Selecting based on hashtags will tend to overestimate bot usage, as hashtags act as magnets for automated activity.

We adjusted the creation dates by subtracting the seven day moving average. This adjustment accounts for fluctuations in when people joined twitter (the platform attracted a large number of Argentine users in 2010).

In the early November, a number of spammers and spoof accounts targeted #Cambiemos. A certain PapaNoelArgento single-handedly produced more than half of the automated content on the hashtag.

The content indicates a probable move to using accounts created by scripts but operated manually.

Fernández described the 19 February rally held after the death of Nisman as a deception across media, involving an arsenal of online and offline techniques. She termed ‘the photographs and their use of perspective, the texts, the occupied common physical space and their capacity’ as a ‘lie’ that produced an inflated image of real levels of support (Fernández de Kirchner 2015). This is the literal translation provided for English-language speakers on her presidential website.

References

Argentina: Macri acusa a oficialismo de campaña sucia - CNN Chile. (2015). CNNChile.com. Retrieved from http://www.cnnchile.com/noticia/2015/11/03/argentina-macri-acusa-a-oficialismo-de-campana-sucia

Ayerdi, R. (2015). Un batallón de 10 mil cibermilitantes en la ola naranja. Perfil.com. Retrieved from http://www.perfil.com/politica/Un-batallon-de-10-mil-cibermilitantes-en-la-ola-naranja-20150628-0026.html

Chen, A. (2015). The Agency. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/07/magazine/the-agency.html

de los Reyes, I. (2015). El secreto detrás de la popularidad de Cristina Fernández en Argentina. BBC Mundo. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/06/150622_argentina_cristina_fernandez_popularidad_irm

Debate presidencial: hallazgos discursivos. (2015). La Nación. Retrieved from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1844150-debate-presidencial-hallazgos-discursivos

El cierre de campaña en las redes sociales: Macri le gana a Scioli. (2015). La Nación. Retrieved from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1847018-el-cierre-de-campana-en-las-redes-sociales-macri-le-gana-a-scioli

El fiscal recibió 53 denuncias contra Cristina por violar la veda electoral. (2015). Clarin.com. Retrieved from http://www.clarin.com/politica/cristina_violacion_veda_electoral_0_1472253234.html

El sciolista que denuncia campaña sucia se burla de Macri y Massa en las redes sociales. (2015a). Clarin. Retrieved from http://www.clarin.com/politica/Elecciones_2015-Scioli-Macri-Massa-Gianella-redes_sociales_0_1414658695.html

Elder, M. (2011). Russians fight Twitter and Facebook battles over Putin election. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/dec/09/russia-putin-twitter-facebook-battles

Fernández de Kirchner, C. (2015). 18F The baptism of fire of the Judicial Party [http://www.cfkargentina.com/18f-the-baptism-of-fire-of-the-judicial-party/].

Filer, T., & Fredheim, R. (2016). Sparking debate? (Political deaths and Twitter discourses in Argentina and Russia) Information, Communication & Society, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1140805.

FpV detalló la denuncia contra Cambiemos. (2015). Ambito.com. Retrieved from http://www.ambito.com/noticia.asp?id=803702

Garrido, N. (2012). Ciberparticipación en Buenos Aires. Los sitios de redes sociales como espacio público. International Review of Information Ethics, 18, 118–126.

Gilbert, J. (2015). In Argentina, a Quiet Data Cruncher Aims to Bring Sense to a Raucous Election. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/22/world/americas/argentina-election-andy-tow.html

Girondo, A. L. (2015). Duran Barba y las lecciones que dejó Ronald Reagan. Tiempo Argentina. Retrieved from http://tiempo.infonews.com/nota/153163/duran-barba-y-las-lecciones-que-dejo-ronald-reagan

Jungherr, A. (2014). The logic of political coverage on Twitter: temporal dynamics and content. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 239–259. doi:10.1111/jcom.12087.

Kejariwal, A. (2015). Introducing practical and robust anomaly detection in a time series. Retrieved November 26, 2015, from https://blog.twitter.com/2015/introducing-practical-and-robust-anomaly-detection-in-a-time-series

Kerr, D. (2012). Mitt Romney suspiciously gets 116K Twitter followers in one day. CNET. Retrieved from http://www.cnet.com/uk/news/mitt-romney-suspiciously-gets-116k-twitter-followers-in-one-day/

Krebs, B. (2014). Spam nation: the inside story of organized cybercrime—from global epidemic to your front door. Naperville: Sourcebooks, Inc.

Kreiss, D. (2014). Seizing the moment: the presidential campaigns’ use of Twitter during the 2012 electoral cycle. New Media & Society, 1461444814562445. doi:10.1177/1461444814562445

Las elecciones marcaron un récord en Facebook. (2015). Infobae.com. Retrieved from http://www.infobae.com/2015/11/23/1771859-las-elecciones-marcaron-un-record-facebook

Las encuestas de los medios: ¿quién ganó el debate en Twitter? (2015). Infobae.com. Retrieved from http://www.infobae.com/2015/11/16/1770039-las-encuestas-los-medios-quien-gano-el-debate-twitter

Macri arrasó en todas las encuestas de Twitter sobre el #ArgentinaDebate. (2015). Perfil.com. Retrieved from http://www.perfil.com/politica/Macri-arraso-en-todas-las-encuestas-de-Twitter-sobre-el-ArgentinaDebate-20151116-0018.html

Menem, C. S. (1989). Libro azul y blanco: toda la verdad que el pueblo quiere saber Menem-Duhalde. Buenos Aires: Editorial Linea Argentina.

Paulsen, M., & Zvereva, V. (2014). Testing and contesting Russian Twitter. In M. Gorham, I. Lunde, & M. Paulsen (Eds.), Digital Russia: The language, culture and politics of new media communication. London: Routledge.

Plotkin, M. B. (2002). Mañana es San Perón: a cultural history of Peron’s Argentina. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources Inc.

Rueda. (2012). 2012’s Biggest social media blunders in LatAm politics. ABC News. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/ABC_Univision/ABC_Univision/2012s-biggest-social-media-blunders-latin-american-politics/story?id=18063022

Russian Twitter political protests “swamped by spam.” (2012). BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-16108876

Schoonderwoerd, N. (2013). 4 ways how Twitter can keep growing—PeerReach Blog. Retrieved from http://blog.peerreach.com/2013/11/4-ways-how-twitter-can-keep-growing/

Senmartin, D. (2014). Social media and diaspora activism: Participating in the Argentine elections 2011 from abroad. In Digital technologies for democratic governance in Latin America (pp. 181–199). Oxford: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.book2look.com/book/9XXz2NNibc.

Sirvén, P. (2014). Macri camina… por las redes sociales. La Nación. Retrieved from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1752269-macri-camina-por-las-redes-sociales

Social media: daily usage in selected countries 2014 | Statistic. (2015b). Statista. Retrieved from http://www.statista.com/statistics/270229/usage-duration-of-social-networks-by-country/

Twitter Developers. (2015). The Search API. Retrieved September 21, 2015, from https://dev.twitter.com/rest/public/search

Valenzuela, S. (2013). Unpacking the use of social media for protest behavior: the roles of information, opinion expression, and activism. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(7), 920–942. doi:10.1177/0002764213479375.

Watts, J. (2015). Argentina elections: Peronist Daniel Scioli ahead by “wide margin.” The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/25/argentina-presidential-elections-2015-voters-polls

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by the Leverhulme Trust (grant number RP2012-C-017).

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Filer, T., Fredheim, R. Popular with the Robots: Accusation and Automation in the Argentine Presidential Elections, 2015. Int J Polit Cult Soc 30, 259–274 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-016-9233-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-016-9233-7