Abstract

Accurate measurement of post-flame temperatures can significantly improve combustion efficiency and reduce harmful emissions, for example, during the development phase of new internal combustion engines and gas turbine combustors. Non-perturbing optical diagnostic techniques are capable of measuring temperatures in such environments but are often technically complex and validation is challenging, with correspondingly large uncertainties, often as large as 2 % to 5 % of temperature. This work aims to reduce these uncertainties by developing a portable flame temperature standard, calibrated via the Rayleigh scattering thermometry technique, traceable to ITS-90, with an uncertainty of 0.5 % of temperature (k = 1). By suitable burner selection and accurate gas flow control, a stable, square, flat flame with uniform post-flame species and temperature is realised. Following development, the standard flame is used to validate two IR emission spectroscopy systems, both measuring the line-integrated emission spectra in the post-flame region. The first utilises a Hyperspectral imaging FTIR spectrometer capable of measuring 2D species and temperature maps and the second, a high-precision single line-of-sight FTIR spectrometer. In the central post-flame region, the agreement between the Rayleigh and FTIR temperatures is within the combined measurement uncertainties and amounts to 1 % (k = 1) of temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

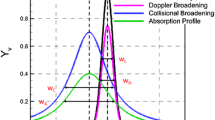

The accurate measurement and control of flame and combustion gas temperatures can lead to increased combustion efficiency, reduced fuel consumption and minimisation of harmful pollutants—for example, NH3/urea solutions added to combustion gases at an optimum temperature can significantly reduce NOx content. Due to the high temperature and hostile nature of the combustion environment, optical diagnostics are the preferred option. The current state-of-the-art favours active probing using laser-based techniques and passive techniques such as gas emission spectroscopy. These techniques have been used in applications such as spark-ignition engines, burner optimisation, high-temperature gas furnaces and incinerators, in an effort to improve process efficiencies and reduce pollutant levels [1,2,3]. However, due to both the complexity of the diagnostic techniques themselves and the harsh environments found in combustion, uncertainties are difficult to assess. Thus, conservative estimates are often used and typically amount to between 2 % and 5 % of the process temperature [1,2,3] and currently, traceability of combustion thermometry to the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90) [4] does not exist. In addition to the excellent contemporary reviews of combustion optical diagnostic techniques of Ehn et al. [5] and Hanson [6], we draw the readers' attention to the work of Goldenstein et al. [7] that describes the advances in Infrared Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (IR-LAS) techniques over the past 15 years. Goldenstein et al. highlight key technological advances that have significantly improved measurement accuracy: the availability of new Mid-infrared sensors and fibres, the development of wavelength modulation techniques and ability to measure at high-repetition rates (up to 100 kHz). In their work, they conclude that limits to the absolute accuracy are primarily due to unsatisfactory accuracy of the spectroscopic databases need to infer temperature and species concentrations from the measurements.

Characterised standard flames can be used for the calibration and verification of optical temperature and concentration measurement techniques. One such artefact [8] employs a commercially available flat flame burner [9] with a sintered porous bronze disk used to stabilise a premixed H2/air flame. Temperatures for various equivalence ratios, flow rates and heights above the burner disk were measured using Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) spectroscopy. An uncertainty of approximately 2.5 % is reported, the accuracy of the CARS measurements being the dominant error contribution. The same system has been used to calibrate Raman scattering apparatus [10, 11] and laser induced fluorescence (LIF) apparatus [12]. Temperatures in the range 1000 °C to 1900 °C were accessible by this method, and the use of chemical equilibrium codes were shown to be in qualitative agreement with the measured CARS values. With measurements made at various heights along the burner axis, a stable temperature region of approximately 10 mm was found to exist. The authors also found that careful selection of the flow rates and equivalence ratio was essential to avoid large heat losses to the water-cooled burner plate. Several other identical burners were also investigated, with the results being the identical within the uncertainty of the measurements. Other investigations of an identical burner [13], using CARS and LIF to characterise the flame, report a temperature uncertainty of approximately the 3 %. A high-pressure burner has also been reported [14] in which the flame is used as a spectroscopic calibration standard. Thermometry performed on this flame is reported to have an accuracy of 1–8 % depending on the fuel/flow conditions. A novel approach to improving both the stability and flatness of a standard flame is reported by Hartung et al. [15], with the development of a premixed flame burner with the ability to support two flames, an inner flat flame that can additionally be seeded with atomic species, such as sodium, for line reversal measurements and an outer flat flame ‘ring’ that can be controlled independently from the inner flame. In conjunction with an embedded water-cooled tube on the circumference of the inner flame region, it was possible to minimise radial differences in flame temperature and improve the uniformity of the inner flame. CARS and sodium line reversal temperature are reported with post-flame temperature uncertainties of less than 1 % claimed, with excellent agreement with chemical kinetic code PREMIX [16].

More recently, Kearney [17] describes a hybrid femto/pico second pulse pure-rotational CARS measurement scheme and reports temperature and oxygen species concentration measurements on a mcKenna premixed flame burner for both H2/air and C2H4/air combustion. Due to the short laser pulse duration, a number of difficulties associated with CARS measurements are reduced: the need for detailed modeling of the collisional broadening of the Raman linewidths is not required and signal contamination from non-resonant background (e.g. soot) is minimised. This results in a claimed single-shot temperature measurement precision of 1 % to 2 %, although an overall uncertainty budget combining the random and systematic uncertainty components is not given.

Several advantages of using these stabilized flames are apparent: (1) the temperature field is reproducible from one burner to another, (2) operation is simple and safe, (3) optical access is unrestricted, (4) the spatial uniformity of the post-flame region is good and (5) a wide range of temperatures and gas compositions are possible by simple variation of the equivalence ratio, flow rate and fuel. To date, standard flames have been predominantly used to calibrate optical diagnostic techniques used in fundamental research activities. However, there is considerable interest in making use of the technology for the calibration and validation of industrial sensors [18].

This work represents a deliverable from the European Metrology Programme for Innovation and Research (EMPIR) project EMPRESS—Enhancing process efficiency through improved temperature measurement [18]. Its objective is to reduce the uncertainty of optical combustion thermometry by developing and characterising a portable standard flame with known and reproducible temperature and species concentrations and demonstrate its utility by validating two independent FTIR emission spectroscopy systems. Both systems measure the line-integrated emission spectra in the post-flame region, with the first at the University of Carlos III Madrid (UC3M) using a moderate resolution hyperspectral imaging FTIR spectrometer, capable of measuring 2D species and temperature maps, and the second, at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) utilising a high-resolution single line-of-sight FTIR spectrometer. First, we present temperature measurements made in the post-flame region of the NPL portable standard flame using laser Rayleigh scattering [19], traceable to ITS-90 with a relative uncertainty (k = 1) of 0.5 %. Second, we describe FTIR emission spectroscopy measurements made on the standard flame by two independent research groups and discuss the level of agreement between the three independent measurements. Finally, we discuss conclusions and prospects for future work.

2 The NPL Standard Flame

The standard flame system comprises a Hencken flat-flame diffusion burner (model #RD1.5X1.5 [20]) and associated gas flow and mixing control. The burner is provided with dry air and propane (C3H8) gas of 95 % purity via Bronkhorst [21] mass flow controllers (MFCs), calibrated with an uncertainty of less than 1 %. Using high-accuracy, stable mass flow controllers, suitably calibrated with the actual process gas (i.e., propane), the stability and reproducibility of the burner is significantly improved. Additionally, the system is portable allowing for easy installation in situ, where in many instances, the optical diagnostic system to be calibrated is not portable. The burner produces a two-dimensional array of small diffusion flamelets stabilized above it, which produces a homogeneous post-flame exhaust gas zone of uniform temperature. By not premixing the fuel and air, the flame is stabilized higher above the burner surface than for a premixed flame [1, 8] reducing heat loss and producing a flame/post-flame temperature close to the theoretical maximum adiabatic flame temperature.

The post-flame temperature depends critically on the height at which the flamelet sheet stabilises above the burner. This height can be controlled by adjusting the airflow rate delivered to the burner (i.e., higher airflow rate, higher stabilisation height). Preliminary tests with two nominally identical Hencken burners identified an airflow rate of 23 SLPM as giving both a flat flamelet sheet and good agreement between the two burners (dT < 0.1 %). This flow rate was used throughout this work. A UV-TRON [22] flame detection sensor observes the burner at all times and triggers a fuel cut-out switch on the propane line 10 s after the flame out condition is detected—this safety feature gives sufficient time to ignite the burner when propane flows but does not allow significant release of flammable gas into the laboratory environment. Additionally, the atmospheric pressure and inlet gas temperatures are monitored and the burner’s position can be adjusted via a motorised XYZ translation stage. LabView [23] software is used to monitor and control the burner system including the facility to programmatically adjust or ramp the airflow rate from 1 to 30 standard litres per minute and the flame equivalence ratio (\( \phi \)) from 0.5 to 2.5. Figure 1 shows the burner under laser interrogation and a schematic of the gas metering and burner control system.

3 Rayleigh Scattering Thermometry

Rayleigh scattering is the elastic scattering of light from atoms, molecules or very small particles—the wavelength of the scattered light is unchanged and the scattering amplitude is proportional to the weighted sum of the number of scatterers in the observation volume. In this work, two Rayleigh scattering signals are measured by observing a high-intensity laser beam passing above the burner. First, a calibration measurement is made by flowing dry air at ambient temperature \( T_{1} \) through the burner giving a signal \( S\left( {T_{1} } \right) \). Second, the signal for the post-flame species at an unknown flame temperature \( T_{2} \) is measured giving \( S\left( {T_{2} } \right) \). Assuming the solid angle of collection \( \Delta\Omega \) is small and the entire width of the incident laser beam is included in the observation area, the signals so measured are given by:

where \( \eta \) is an instrument factor, \( I \) is the incident laser intensity and \( V \) is the observation volume. \( N_{1} \) and \( N_{2} \) are the number density of scatters present during the air calibration and post-flame measurements, respectively. \( \left( {\partial \sigma /\partial\Omega } \right)_{air} \) and \( \left( {\partial \sigma /\partial\Omega } \right)_{f} \) are the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-sections of the air and post-flame gases, respectively. For atmospheric pressure flames, the ideal gas law can be applied, leading to:

where \( k \) is the Boltzmann constant. By combining Eqs. 1 and 2 it is possible to write:

with

\( T_{1} \) is measured with a calibrated PT100 sensor traceable to ITS-90 prior to the flame measurement. \( \delta \) accounts for the difference in the scattering cross-section between the air calibration and flame measurements. To obtain \( T_{2} \), accurate knowledge of \( \delta \) is required. To achieve the lowest uncertainty in the flame temperature measurements, the species and temperature dependence of \( \delta \) are taken into account. A complete description of how the Rayleigh scattering cross-section, its temperature dependence and the species concentrations in the post-flame region are determined is given in Appendix A and additionally, we refer the reader to our earlier work [1, 2, 19] for more information.

3.1 Experimental Setup

The precision laser Rayleigh scattering thermometry system is shown in Fig. 2. A CW laser beam produced by a Coherent Verdi G10 [24], operating at 532 ± 2 nm, passes above the burner and the Rayleigh scattered light is collected perpendicular to it via a temperature-stabilized silicon trap detector.

To minimise the amount of background laser light collected by the detector, a number of adjustable irises and apertures are used. To determine the remaining background level, air, nitrogen (99.99 % purity) and helium (99.999 % purity) where consecutively flowed through the burner and the Rayleigh signals measured. By assuming that the signals contain a constant background component and a component proportional to the Rayleigh scattering cross-section of each gas, it was possible to determine the background scatter level relative to one of the three gases. The final level of background scatter was 0.026 % of the measured Rayleigh signal for air. This is equivalent to 0.17 % of the typical flame Rayleigh signal, which is bordering on being a significant systematic error—for this reason, the background scatter was re-determined regularly and subtracted from the measured signals prior to further processing.

3.2 Measurements

Rayleigh scattering signals are small—for these experiments, they amounted to approximately 4 nW and 0.6 nW for measurements in ambient air and flames, respectively. It is, therefore, important to use a detector with high gain and stability, and low noise. We chose to use a trap detector, consisting of three Hamamatsu 1331 [25] (10 mm × 10 mm) silicon photodiodes. The photocurrent is amplified by a transimpedance amplifier utilising an OPA128LM integrated circuit with a gain of 109 V·A−1. The detector-amplifier combination is thermally insulated, and temperature stabilized to within ± 25 mK at around 30 K. Temperature stabilisation minimises gain changes in the amplifier and offset drifts.

The probe laser beam was focussed to a beam waist of 0.1 mm, 20 mm above the centre of the burner and then captured by a high-efficiency beam dump. The Rayleigh scattered light was collected perpendicular to the probe beam, over a 0.1 sr solid angle (defined by two knife-edged imaging apertures) via a 1:1 imaging system with a 75 mm diameter lens doublet. It was then focused on to a laser-line filter (\( \lambda \) = 532 ± 2 nm, 10 ± 2 nm FWHM) and on to a 3 mm × 3 mm precision square defining aperture on the front of the of the trap detector.

Software written in Labview 2015 [23] was used to control the laser power, detector and laser shutters, and the data acquisition process. For each data point, the Rayleigh, ambient background and detector zero signals were measured and when required (i.e., during air calibration), the temperature of a calibrated PT100 was also measured. Through a network connection to the burner control system, the air flow rate, propane flow rate, equivalence ratio, gas inlet temperatures and the position of the XYZ-stage were also captured. Following each measurement, all data were saved to file for later processing.

The raw detector voltages were captured by a 16-bit National Instruments PCIe-6321 data acquisition card. A single capture consisted of measuring 100 k samples at 100 kHz sample rate (1 s acquisition time), removing any spikes and then averaging all remaining points. These measurements identified a minor ‘flicker’ in the Rayleigh signal intensity with a frequency of approximately 12 Hz, resulting in an equivalent temperature variation of approximately ± 10 °C. This variation is minimised by averaging over 1 s and could be further reduced by averaging repeated measurements.

The measurement sequence consisted of: (1) detector and laser shutters closed—measure the detector zero, (2) detector shutter open, laser shutter closed—measure the ambient background, (3) detector and laser shutters open—measure the Rayleigh + ambient background signal and (4) determine the absolute Rayleigh signal by subtracting the ambient background signal. In all cases, the detector zero offset was small due to good thermal control of the trap detector, but any such errors were removed by this process. Post-processing of the captured data was performed with Labview 2015 to determine the post-flame temperature \( T_{2} \) according to the method described in Appendix A.

Prior to igniting the flame, the air calibration measurement is made. A PT100 sensor is placed adjacent the burner surface while air flows through it and the Rayleigh signal measured. This constitutes the air calibration measurement [\( T_{1} , P_{atm} , S\left( {T_{1} } \right) \)]. The PT100 sensor is then moved away from the burner and the burner flame ignited. After a period of 60 min, the burner has warmed up and the flame temperature is stable. The Rayleigh signal \( S\left( {T_{2} } \right) \) is then measured in the post-flame region. Two sets of measurements were made:

3.2.1 Medium-Term Temperature Measurements

To establish the medium-term stability and reproducibility of the standard flame, measurements were made of the post-flame temperature for propane/air equivalence ratios of \( \phi = \left\{ {0.8 - 1.4} \right\} \) in 0.1 steps. These measurements were then repeated a further nine times on separate days, over a 3-month period. All measurements were performed in the region 20 mm above the burner centre.

3.2.2 Temperature Profiles

To establish the spatial variation in the temperature field above the burner, a series of profiles in the x and y-directions were measured at heights of 10 mm, 20 mm and 30 mm above the burner surface. The temperature profiles were measured from \( R_{x} \) = − 20 mm to \( R_{x} \) = + 20 mm and from \( R_{y} \) = − 20 mm to \( R_{y} \) = + 20 mm, i.e., \( R_{x} \) is the position in the x-direction relative to the burner centre. These measurements were then repeated with the addition of a nitrogen (N2) gas co-flow. The co-flow was delivered through a mesh surrounding the central flame/air tubes. During the measurements, the N2 output regulator was held at a gauge pressure of 0.5 bar, this gave a co-flow rate of approximately 100 SLPM. Figure 3 shows the burner, the scan orientations and the N2 co-flow region.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Medium-Term Temperature Measurements

Figure 4a shows the mean temperature \( T_{2} \) measured 20 mm above the burner centre for \( \left\{ {0.8 < \phi < 1.4} \right\} \) over a 3-month period (10 days measurements). The adiabatic flame temperature \( T_{ad} \) is also shown and represents the theoretical maximum temperature the flame can attain if there are no heat losses. This is never achieved in practice since there are always heat losses to the burner surface and the external environment. For all \( \phi \), the temperature is lower than \( T_{ad} \) by between 1 % and 2 %. Additionally, the measurement data sits symmetrically below the \( T_{ad} \) curve, indicating that the mass flow controllers used to meter the air and propane are operating within their calibration uncertainty. If this had not been the case, a systematic offset would be clearly evident.

The standard deviation of the temperature measurements is shown in Fig. 4b). Depending on \( \phi \), it ranges from 2.4 K to 4.6 K (0.12 % to 0.2 % of \( T_{2} \)). This is a remarkable level of reproducibility and demonstrates the suitability of the Hencken burner and associated gas flow and control system as a standard flame. Additionally, there is no apparent correlation between the post-flame temperature \( T_{2} \) and the air calibration temperature \( T_{1} \), the inlet air/propane temperatures, or the atmospheric pressure during the measurement. The overall uncertainty in each temperature measurement is estimated to be \( U_{r} \left( T \right) \) = 0.5 %. An uncertainty budget can be found in Appendix B1.

3.3.2 Temperature Profiles

Figure 5 shows the horizontal temperature profiles for \( \phi \) = 1.0, based on the mean of ten measurements. \( \left( {R_{x} ,R_{y} ,R_{z} } \right) \) is the measurement location relative to a point 20 mm above the burner centre (see Fig. 3), and negative \( R_{z} \) are further away from the burner. The profiles are given for (a) no co-flow and (b) N2 co-flow. We confirm that the temperature in the post-flame region is relatively uniform, at least, over the central ± 10 mm horizontal region. We also see that the extent of the ‘flat’ region reduces as we move further away from the burner surface—this is also evident visually in Fig. 1a). Additionally, in the central ± 10 mm (vertically and horizontally), the temperature range is no greater than ± 1 %. We also note that, in this case, the addition of the co-flow (Fig. 5b) improves the uniformity of the post-flame temperature. For a full description and interpretation of the results for \( \phi = \left( {0.8, 1.0, 1.4} \right) \), the reader is directed to our earlier publication [19].

Temperature profiles for \( \phi \) = 1.0, with (a) no co-flow, (b) N2 co-flow. (Rx, Ry, Rz) is the measurement location relative to a point 20 mm above the burner centre (see Fig. 3), and negative RZ are further away from the burner

3.3.3 Long-Term Temperature Reproducibility

The standard flame was initially calibrated in May 2016. Over the following 2½ years, it was moved to three combustion research groups: UC3M (Madrid, Spain), Oxford University—UOX (Oxford, UK) and DTU (Roskilde, Denmark), returning for calibration checks in May 2017, Jan 2018 and Nov 2018, respectively. Figure 6 shows the shift in flame temperature (20 mm above the burner centre) measured during these calibration checks. We see that, although chronologically, a minor upward drift is apparent, the temperatures are still within the expected calibration uncertainty—i.e., for our claimed uncertainty of \( U_{r} \left( T \right) = \pm 0.5 \) % (68 % confidence interval), it would be reasonable to expect variations of at least \( U_{r} \left( T \right) = \pm 1 \) % (95 % confidence interval). We regard this as compelling evidence for the suitability of the standard flame as a calibration source.

4 FTIR Emission Spectroscopy Measurements Made on the Standard Flame

Following calibration of the standard flame, temperature measurements were made using two independent FTIR emission spectroscopy systems. Both systems measured the line-integrated emission spectra in the post-flame region, with the first at the University of Carlos III Madrid (UC3M) using a moderate resolution hyperspectral imaging FTIR spectrometer capable of measuring 2D species and temperature maps, and the second at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) utilising a high-resolution, high-precision single line of site FTIR spectrometer.

4.1 Principle of Measurement

The spectral intensity along a line-of-sight as seen by the FTIR spectrometer at \( s = L \) is given by [26]:

where \( \eta \) is the wavenumber, \( \kappa_{\eta } \) is the absorption coefficient, \( I_{b\eta } \) is the blackbody spectral intensity (which depends on both temperature and wavenumber), and \( I_{0\eta } \) is the spectral intensity at \( s \) = 0 (background).

For numerical calculations, we assume that over a small path length \( \Delta s \), both the temperature \( T \) and absorption coefficient \( \kappa_{\eta } \) are constant. Equation 4 can then be discretised, and written as:

Where \( I_{i} \left( \eta \right) \) is the spectral intensity leaving the ith sub-path and \( \kappa_{\eta i} \) is the absorption coefficient for the temperature and gas concentration of the ith sub-path.

By making use of Eq. 5 and the HITEMP2010 spectral database [27] for CO2, H2O and CO spectral lines over the range 1500 cm−1 to 2400 cm−1 (4.2 μm–6.7 μm), and an initial estimate of the post-flame temperature and composition, an emission spectrum can be synthesised. By minimizing the difference between the measured and synthesised spectra iteratively, the flame temperature can be determined.

4.2 Instrumentation and Measurements

4.2.1 UC3M

The UC3M hyperspectral imager, described in detail in [28, 29], is a FTIR hyperspectral Imaging System (Telops Hypercam IFTS) operating in the extended MIR region, from 1800 cm−1 to 5000 cm−1. This system has a Michelson interferometer coupled to an InSb focal plane array (FPA), with 320 × 256 pixel resolution, with an instantaneous (pixel) field of view of 0.35 mrad and a maximum resolution of 0.25 cm−1. To reduce acquisition time, in this work, all spectra have been measured at 0.5 cm−1 in a sub window of 160 × 256 pixels. Additionally, low-frequency fluctuations in the raw interferograms due to flame flickering were corrected for [30]. Interferogram processing included triangular apodization, phase correction to remove small sampling asymmetries in the interferogram, and off-axis wavenumber correction [28, 29].

To enable the system to measure in radiance units, it was radiometrically calibrated at Centro Español de Metrología (CEM). Two blackbodies were used with an aperture large enough to cover the whole field of view of the 160 × 256 sub window (70 mm diameter). Calibration temperatures were 180 °C and 400 °C. Since the spectral emission of the flame is concentrated in a narrow band in comparison to the full spectral range of the instrument, these blackbody temperatures were sufficient to calibrate the instrument for flame temperatures up to 2400 °C [31], The calculated emissivity of these BBs is 0.981 and 0.985, respectively. The BBs temperature has been measured with a RT HEITRONICS TRTII working at 3.9 μm, traceable to the national standards.

During measurements, the imager was placed 1.55 m away from the standard flame and a correction applied for absorption in the intervening path. Since the temperature needs to be determined for each pixel in the image, the computational requirement would be prohibitive if detailed temperature/species profile were fitted. To reduce this overhead and aid simplicity, flat temperature/species profiles were assumed throughout this aspect of the work and the measurements should be regarded as effective line-of-sight averages. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 7a) with the imager viewing the standard flame.

A first set of measurements were made for \( \phi = \left\{ {0.8, 1.0, 1.4} \right\} \), with the data extracted for heights above the burner (HAB) of 10 mm, 20 mm and 30 mm; in each case, with and without N2 co-flow. For each experimental condition, four interferograms were acquired and averaged, with an integration time of 25 μs. Three months later, a second set of measurements were made under the same conditions but with \( \phi = \left\{ {0.9,1.0,1.2} \right\} \) and additionally, the \( \phi = 1.0 \) measurements were repeated a second time with the burner rotated by 90°. The repeat measurements and those with the burner rotated were in good agreement. An uncertainty budget for the UC3M measurements can be found in Appendix B2.

4.2.2 DTU

The DTU FTIR-spectrometer, shown in its measurement configuration in Fig. 7b) is an Agilent model 660, equipped with a liquid nitrogen cooled narrow band high-sensitivity linearized mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) detector and KBr beam-splitter, which is capable of conducting measurements in the spectral range of 650–8000 cm−1 with a highest nominal spectral resolution of 0.09 cm−1. The spectrometer was operated in fast scanning mode to reduce flame flickering effects on measured interferograms. All optical paths (from A1 to A4 and the FTIR itself) are purged with N2 (99.999%) during the measurements and the purge flow was adjusted to avoid cooling effects on the flame edge. A silver reflection screen along the flame height was used to reduce the effects of flame radiation on the FTIR’s thermal stability. Raw interferograms were obtained during the measurements and a triangular apodization function was used for calculations of a single beam. The system was calibrated in radiance units with a portable calibrated blackbody at 796 °C and was re-calibrated after each measurement sequence. Background measurements (without blackbody and standard flame) were also taken, which were subtracted from the corresponding flame/blackbody measurements to eliminate background emission effects. Unlike the UC3M measurements, a flat temperature/species profile was not assumed for the DTU measurements. This allowed for an extra degree of freedom when minimizing the differences between the synthesized and measured spectra and improved agreement between the DTU and NPL results.

Measurements were made for \( \phi = \left\{ {0.8,1.0,1.4} \right\} \) for HAB of 10 mm, 20 mm and 30 mm viewing in the Rx direction, scanning in the Ry direction, with the majority of measurements being performed with no N2 co-flow. In some cases, it was possible to reduce the differences between the synthesized and measured spectra further by adjusting the temperature profile at the horizontal extremities of the burner, a region where uncertainty in the Rayleigh scattering temperature measurements is largest. A discussion of the uncertainty budget for the DTU measurements can be found in Appendix B3.

4.3 Results—UC3M

Figure 8 shows an example of the measured temperature and species maps of the standard flame for stoichiometric \( \left( {\phi = 1.0} \right) \) conditions without co-flow. The final result after full processing of the experimental data is a set of images that map temperatures T [K] and column densities Q [ppm·m]. Temperatures are the line-of sight averages for the flame, whereas a column density map is obtained for each chemical species studied [32] (in this case, CO2, CO and atmospheric CO2). The imaging capability of the hyperspectral imager allows us to clearly identify the flame geometry—including the uniform temperature region and CO production region close to the burner-stabilized flat-flame boundary. Figure 9 shows a comparison of the mean post-flame temperature (average of the central 10 mm region) of the standard flame for \( HAB = \left\{ {10\,{\text{mm}},20\,{\text{mm}},30\,{\text{mm}}} \right\} \). UC3M—hyperspectral imaging (solid markers), NPL—Rayleigh scattering (hollow markers). The inset shows the temperature differences: T(UC3M)—T(NPL) for selected \( \phi \). Where comparison data exist \( \left( {\phi = \left\{ {0.8,1.0,1.4} \right\}} \right) \), there is excellent agreement between the two independent measurements, with the worst level of agreement for \( \phi = 1.4 \) being at most 1 %, which is still within the combined uncertainty of the two measurements.

Figure 10 shows a comparison of the temperature profiles measured in the post-flame region of the standard flame for \( HAB = \left\{ {10\,{\text{mm}},20\,{\text{mm}},30\,{\text{mm}}} \right\} \). UC3M—hyperspectral imaging (solid markers), NPL—Rayleigh scattering (hollow markers). Several trends are apparent: (a) agreement is very good for lean \( \left( {\phi = 0.8} \right) \) and stoichiometric \( \left( {\phi = 1.0} \right) \) flames and (b) agreement is poorer for increasing height above the burner and for rich flames \( \left( {\phi = 1.4} \right) \).

The overall agreement in temperatures between NPL and UC3M is within the combined measurement uncertainties (1 % of T) for lean and stoichiometric flames. However, discrepancies appear for rich flames \( \left( {\phi = 1.4} \right) \), where agreement between the two techniques, at the outer edges of the post-flame region (Rx > 10 mm), is poorer. This is clearly seen for HAB = 20 mm and 30 mm, where the Rayleigh temperatures are systematically lower than the hyperspectral imaging temperatures. It is not clear why this should be the case, however, we speculate that it may be due to several factors. First, for larger heights above the burner, the exhaust gas may mix with ambient air. This would reduce the actual temperature but also change the Rayleigh scattering cross-section, resulting in larger uncertainties in the derived Rayleigh temperatures at the extremities of the exhaust gas region. Second, the hyperspectral imaging measurements integrate the emission over a defined path length. This path length is defined by the width of the exhaust gas region and is one of the parameters needed in the model to extract the temperature. For larger heights above the burner, this width reduces and the precision with which it can be determined may increase, leading to temperature errors.

4.4 Results—DTU

The temperature stability of the STD flame is examined in Fig. 11, where the relative difference between two measured emission spectra for HAB = 20 mm and \( \phi = 1 \), taken an hour apart is shown. The difference is consistent over the range considered and amounts to 1.4 % or 1.8 % when considering the line average or integral difference, respectively. Because of this consistency, the difference is most likely due to a small change in the CO2 concentrations (due to a change in ambient pressure) rather the gas temperature. Typically, the reproducibility of the measurements, e.g. at \( \phi = 1 \), HAB = 20 mm in the 2200–2400 cm−1 and 3200–3700 cm−1 spectral ranges, are better than 2 % and 5 %, respectively, for time spans from minutes to days.

Because analysis of the experimental data relies on modeling with the HITEMP2010 database, it is important to investigate the spectral limits where the database can be used. In Fig. 12 the emission spectrum for HAB = 22 mm and \( \phi = 1.0 \) is shown. The spectrum is measured along the burner centerline, where one can expect the most stable and reliable temperature profile data from NPL, and a comparison is made between calculations and measurements based on the integrated signals (i.e., area under the curve). Species concentrations have been obtained from fitting the measurements, assuming a constant concentration across the flame and the NPL provided temperature profile.

Comparison of DTU measured and synthesized (via HITEMP2010, with NPL measured temperature profile) emission spectra for \( \phi = 1.0 \), HAB = 22 mm. Species concentrations have been obtained from fitting the measurements, assuming a constant concentration and NPL’s provided temperature profile. The solid black lines indicate the limits to the spectral ranges used

We see from the figure that the overall difference between measured and modelled spectra in 1500–2400 cm−1 range (CO2, H2O, CO lines) is 1.25 %. For the H2O lines (with a small CO contribution) in the range 1500–2000 cm−1, the difference is 0.63 % whereas for CO2 (with a small CO contribution) in 2160–2400 cm−1 the difference is − 0.17 %. This CO2 band has highest intensity in the overall emission spectrum (600–6000 cm−1) and is most sensitive to variations in the temperature profile, whereas, the H2O band is less sensitive. Therefore the CO2 band 2160–2400 cm−1 was used for the validation of NPL’s temperature profiles that are presented next.

Figure 13 shows a comparison of the DTU measured and fitted flame spectra (using the NPL temperature profiles) for HAB = 20 mm, for (a) \( \phi = 0.8 \), (b) \( \phi = 1.0 \), and (c) \( \phi = 1.4 \). The fitting residuals are shown in red. For \( \phi = 1.0 \) and \( \phi = 1.4 \), the CO contribution is shown separately (grey). The inset tables show a comparison of the measured species concentrations with those from chemical equilibrium calculations (GasEq [33]). We do not expect perfect agreement between the two, since the latter assume adiabatic conditions, however, we would expect the level of agreement to be reasonable as the flame temperatures are only a few percent cooler that the adiabatic case. As previously, the species concentrations were assumed constant along the line of sight of the measurement. The agreement between the measured and fitted spectra are excellent, and the corresponding fitting residuals are small. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, the fitting was performed by minimizing the differences in the region of strongest emission of the CO2 band (2160–2400 cm−1), which has the strongest sensitivity to temperature. As a result it can be seen that there is a systematic offset in the residuals in the region 2000–2160 cm−1. This is a region where HITEMP2010 is known to have poorer accuracy. Thus, our measurements may offer the potential to improve spectroscopic parameters, although this is outside the scope of this current work.

Comparison of DTU measured and fitted flame spectra (using the NPL temperature profiles), for HAB = 20 mm, for (a) \( \phi = 0.8 \), (b) \( \phi = 1.0 \), and (c) \( \phi = 1.4 \). The fitting residuals are shown in red. For \( \phi = 1.0 \) and \( \phi = 1.4 \), the CO contribution is shown in separately (grey). The inset tables show a comparison of the measured species concentrations with those from chemical equilibrium calculation (GasEq [33]) (Color figure online)

During the FTIR spectral fitting process, it became apparent that in the case of \( \phi = 0.8 \) and \( \phi = 1.0 \), the magnitude of the fitting residuals could be further reduced if the assumed NPL Rayleigh temperature profiles were adjusted slightly. Figure 14 shows examples of this, with the Rayleigh measurements shown with blue circles for both \( \phi \). By iteratively adjusting the assumed temperatures, close to the flame boundary (|x| > 1 cm), where the uncertainty in the Rayleigh temperatures is largest, it was possible to reduce the FTIR fitting residuals and improve the quality of the temperature profiles.

Comparison of NPL Rayleigh and DTU FTIR boundary correct temperature profiles for HAB = 20 mm, for (a) \( \phi = 0.8 \) and (b) \( \phi = 1.0 \). By systematically adjusting the assumed temperatures close to the flame boundary (|x| > 1 cm), where the uncertainty in the Rayleigh temperatures is largest, it was possible to reduce the FTIR fitting residuals and improve the temperature profiles

The spectral region 2160–2400 cm−1 was identified as being most sensitive to changes in flame temperature, with agreement between the measured emission spectra and that calculated from HITEMP2010 using the NPL Rayleigh temperature profiles being better than 0.2 % in terms of the absolute band-integrated signal. Measurements for \( \phi = \left\{ {0.8, 1.0, 1.4} \right\} \) also show excellent agreement with the spectroscopic model/NPL temperature profile. This may be regarded as confirmation that the temperatures measured by the two independent techniques are in good agreement. By iteratively adjusting the NPL Rayleigh temperature profiles for \( \phi = \left\{ {0.8, 1.0} \right\} \), for regions of the flame close to the flame/air boundary (|x| > 1 cm), we were able to further minimise the differences between the measured and modelled spectra. In this region, the Rayleigh temperature measurements have the largest uncertainty due to poorer flame stability and poorer knowledge of the gas composition.

It is worthy of note that the optical thickness of the NPL post-flame region is low (\( kL \ll 1 \) in the maximum of the CO2 emission band at 2300 cm−1, \( k \) = absorption coefficient, \( L \) = post-flame dimension) meaning that the CO2 emission band does not reach the blackbody continuum level. The later can, however, happen when the \( L \) is more than 15 cm at CO2 concentrations typical for propane combustion.

5 Summary and Conclusions

A portable flame temperature standard has been developed and calibrated traceably to ITS-90 using the Rayleigh scattering thermometry technique. By taking into account the variation in the differential Rayleigh scattering cross-section with both species and temperature, it has been possible to measure the post-flame temperature (for the default measurement position—20 mm above the burner centre) with a relative uncertainty \( \left( {1\sigma } \right) \) of 0.5 %. For the same measurement position, the medium-term temperature reproducibility (over a 3-month period) was found to be 0.2 % of \( T \). Additionally, by careful control of the equivalence ratio \( \phi \), the standard flame system was also capable of realising a number of fixed post-flame temperatures in the range 2040 K–2255 K with known species concentrations. Post-flame temperature profiles indicate a uniform region where the temperature varies horizontally and vertically by at most ± 0.5 % and ± 1.0 % respectively for any point within 10 mm of the default measurement position. Over a 2½ year period, following three off-site trials, the long-term stability of the standard flame system was found to be better than 0.5 % of temperature, further demonstrating the suitability of the system as a temperature standard.

Measurements made on the standard flame using a hyperspectral FTIR imager and single line-of-sight FTIR spectrometers have been presented and demonstrate excellent agreement within the combined uncertainties of the measurement systems (1 % of T (k = 1)). In the case of the single line-of-sight measurements, it has been possible to refine the reported Rayleigh temperatures close to the flame/air boundary (where uncertainty in the temperature measurement is largest) by iterative adjustment and minimisation of the differences between measured and modelled emission spectra. Additionally, measurements made by both spectrometers have confirmed the quality of the HITEMP2010 database in the 1500–2400 cm−1 spectral range: if the database contained significant errors, it would not have been possible to generate synthetic spectral that were in such good agreement with measured spectra over the entire spectral range. Similarly, if the Rayleigh temperature measurements contained significant errors, it would not have been possible to match synthesised and measured spectra. The level of agreement between the three measurement systems may be attributed the fact that they were all made under laboratory conditions. We would expect significantly larger differences under non-ideal conditions. We aim to address this in the project EMPRESS2 [34] where NPL, UC3M/CEM and DTU will develop two practical FTIR instruments to facilitate flame temperature measurements in challenging industrial environments. This work will be reported in the future.

References

G. Sutton, A. Levick, G. Edwards, D. Greenhalgh, A combustion temperature and species standard for the calibration of laser diagnostic techniques. Combust. Flame 147, 39–48 (2006)

G. Sutton, The development of a combustion temperature standard for the calibration of optical diagnostic techniques, Ph.D. Thesis, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, UK (2005)

G.J. Edwards, S.J. Boyes, Review of the status, traceability and industrial application of gas temperature measurement techniques, Report CBTM-S1, National Physical Laboratory (1997)

H. Preston-Thomas, The international temperature scale of 1990 (ITS-90). Metrologia 27, 3–10 (1990)

Andreas Ehn, Jiajian Zhu, Xuesong Li, Johannes Kiefer, Advanced laser-based techniques for gas-phase diagnostics in combustion and aerospace engineering. Appl. Spectrosc. 71, 341–366 (2017)

K. Ronald, Hanson, applications of quantitative laser sensors to kinetics, propulsion and practical energy systems. Proc. Combust. Inst. 33, 1–40 (2011)

C.S. Goldenstein, R.M. Spearrin, J.B. Jeffries, R.K. Hanson, Infrared laser-absorption sensing for combustion gases. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 60, 132–176 (2017)

S. Prucker, W. Meier, W. Stricker, A flat flame burner as calibration source for combustion research: temperature and species concentrations of premixed H2/air flames. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 65, 2908–2911 (1994)

The McKenna Flat Flame Burner, Holthuis & Associates, P.O. Box 1531, Sebastopol, CA 95473, U.S.A

S. Prucker, W. Meier, I. Plath, W. Stricker, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 96, 1393 (1992)

W. Meier, S. Prucker, W. Stricker, The Third International Symposium On Special Topics In Chemical Propulsion: Non-Intrusive Combustion Diagnostics (Begell House, New York, 1994)

K. Kohse-Höinghaus, U.E. Meier, The Third International Symposium on Special Topics in Chemical Propulsion: Non-intrusive combustion diagnostics (Begell House, New York, 1994)

Y.S. Gil, S.H. Chug, Combustion characteristics of a planar flame burner as a calibration source of laser diagnostics. SPIE, 2778, Optics for science and new technology (1996)

J. Kojima, Q.-V. Nguyen, Development of a High-Pressure Gaseous Burner for Calibrating Optical Diagnostic Techniques (Glenn Research Centre, Cleveland, 2003)

G. Hartung, J. Hult, C.F. Kaminski, A flat flame burner for the calibration of laser thermometry techniques. Meas. Sci. Technol. 17, 2485 (2006)

R.J. Kee, J.F. Grcar, M.D. Smooke, J.A. Miller, A FORTRAN program for modelling steady laminar one-dimensional premixed flames, Sandia National Laboratories Report SAND85-8240 (1993)

P. Sean, Kearney, Hybrid fs/ps rotational CARS temperature and oxygen measurements in the product gases of canonical flat flames. Combust. Flame 162, 1748–1758 (2015)

J.V. Pearce, F. Edler, C.J. Elliott, L. Rosso, G. Sutton, R. Zante, G. Machin, A European project to enhance process efficiency through improved temperature measurement: EMPRESS. In: 17th International Congress of Metrology, 08001, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1051/metrology/201508001

G. Sutton, A. Greenen, L. Stanger, M. de Podesta, The NPL portable standard flame: characterisation of the temperature field above the burner using precision Rayleigh scattering thermometry, NPL Report ENG 69 (2018)

The Hencken burner, Technologies for Research, Inc, 2665 Calle Alegre, Pleasanton, CA 94566

Bronkhorst (UK) Ltd, 1 Kings Court, Willie Snaith Road, Newmarket, Suffolk CB8 7TG, http://www.bronkhorst.co.uk/

UV-TRON. http://www.hamamatsu.com/resources/pdf/etd/UVtron_TPT1034E.pdf

Labview, National Instruments Corporation, 11500 N Mopac Expwy, Austin, TX 78759-3504

Coherent UK Ltd, St Thomas Place, The Cambridge Business Park, Ely, CB7 4EX, United Kingdom

Hamamatsu Photonics UK Ltd, 2 Howard Court, Tewin Road, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, AL7 1BW, United Kingdom

M.F. Modest, Radiative Heat Transfer, 3rd edn. (Academic Press, New York, 2013)

L. Rothman, I. Gordon, R. Barber, H. Dothe, R. Gamache, A. Goldman, V. Perevalov, S. Tashkun, J. Tennyson, HITEMP, the high temperature molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quan. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 111, 2139–2150 (2010). In: {XVIth} Symposium on high resolution molecular spectroscopy (HighRus-2009) XVIth symposium on high resolution molecular spectroscopy

M.A. Rodríguez-Conejo, J. Meléndez, Hyperspectral quantitative imaging of gas sources in the mid-infrared. Appl. Opt. 54, 141–149 (2015)

M.A. Rodríguez-Conejo, Teledetección de gases mediante imagen hiperespectral por transformada de Fourier en el infrarrojo medio, Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (2016)

G. Keppel-Aleks, G.C. Toon, P.O. Wennberg, N.M. Deutscher, Reducing the impact of source brightness fluctuations on spectra obtained by Fourier transform spectrometry. Appl. Opt. 46, 4774–4779 (2007)

M.A. Rodríguez-Conejo, G. Guarnizo, J. Meléndez, F. López, M.J.M. Hernández, J.M. Mantilla, M.D. Del Campo Maldonado, Measurement of temperature and gas concentration in a Bunsen burner flame based on a hyperspectral imager. In: XIII international symposium on temperature and thermal measurements in industry and science (TEMPMEKO) Zakopane, Poland (2016)

M.R. Rhoby, D.L. Blunck, K.C. Gross, Mid-IR hyperspectral imaging of laminar flames for 2-D scalar values. Opt. Express 22, 21600–21617 (2014)

C. Morely, A chemical equilibrium package for Windows, (2004) http://www.gaseq.co.uk

EMPRESS2—Enhancing process efficiency through improved temperature measurement, 17IND04, May 2018–April 2021. https://www.euramet.org/research-innovation/search-research-projects/details/?eurametCtcp_project_show%5Bproject%5D=1531&eurametCtcp_project%5Bback%5D=450&cHash=9dabe2193815a666940e332e9bb60883

R.B. Miles, W.R. Lempert, J.N. Forkey, Laser rayleigh scattering. Meas. Sci. Technol. 12, R33–R51 (2001)

W.C. Gardiner Jr., Y. Hidaka, T. Tanzawa, Refractivity of combustion gases. Combust Flame. 40, 213–219 (1981)

J. Fielding, J.H. Frank, S.A. Kaiser, M.D. Smooke, M.B. Long, Polarized/depolarized rayleigh scattering for determining fuel concentrations in flames. Proc. Comb. Inst 29, 2703–2709 (2002)

U. Hohm, K. Kerl, Interferometric measurements of the dipole polarisability, α, of molecules between 300 K and 1100 K: I. Monochromatic measurements at λ = 632.99 nm for the noble gases and H2, N2, O2 and CH4. Mol. Phys. 69, 803–817 (1990)

J.A. Sutton, J.F. Driscoll, Rayleigh scattering cross sections of combustion species at 266, 355, and 532 nm for thermometry applications. Opt. Lett. 29, 22 (2004)

J. Rychlewski, Frequency dependent polarizabilities for the ground state of H2, HD, and D2. J. Chem. Phys. 78, 7252–7259 (1983)

Evaluation of measurement data—guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement, JCGM 100:2008, GUM 1995 with minor corrections, BIPM (2008)

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge and thank Mª José Martín and José Manuel Mantilla of CEM for their invaluable contribution to this work, in performing the radiometric calibration of the UC3M hyperspectral imager. Additionally, we would like to thank Alberto Sposito for help with the Rayleigh measurements and Michael de Podesta for constructive comments during preparation of this manuscript. This project has received funding from the EMPIR programme co-financed by the Participating States and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Number 14IND04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Rayleigh Scattering Thermometry Theory

1.1 Principle of Measurement

In this work, two Rayleigh scattering signals are measured by observing a high-intensity laser beam passing above the burner. First, a calibration measurement is made by flowing dry air at ambient temperature \( T_{1} \) through the burner giving a signal \( S\left( {T_{1} } \right) \). Second, the signal for the post-flame species at an unknown flame temperature \( T_{2} \) is measured giving \( S\left( {T_{2} } \right) \). Assuming the solid angle of collection \( \Delta\Omega \) is small and the entire width of the incident laser beam is included in the observation area, the signals so measured are given by:

where \( \eta \) is an instrument factor, \( I \) is the incident laser intensity and \( V \) is the observation volume. \( N_{1} \) and \( N_{2} \) are the number density of scatters present during the air calibration and post-flame measurements, respectively. \( \left( {\partial \sigma /\partial\Omega } \right)_{air} \) and \( \left( {\partial \sigma /\partial\Omega } \right)_{f} \) are the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-sections of the air and post-flame gases, respectively. For atmospheric pressure flames, the ideal gas law can be applied with negligible error, leading to:

where \( k \) is the Boltzmann constant. By combining Eqs. 6 and 7 it is possible to write:

with

with \( T_{1} \) measured with a calibrated PT100 sensor prior to the flame measurement. \( \delta \) accounts for the difference in the scattering cross-section between the air calibration and flame measurements. To obtain \( T_{2} \), accurate knowledge of \( \delta \) is required.

1.2 Essential Theory

The total Rayleigh scattering cross-section for a single species can be written as [35]:

where \( n\left( \lambda \right) \) is the refractive index of the species at the laser wavelength \( \lambda \), \( N \) is the number density of the species and \( p_{0} \left( \lambda \right) \) is the depolarisation ratio, which is given by:

with \( \gamma \) and \( \alpha \) the molecular anisotropy and mean molecular volume polarizability respectively. These are also wavelength dependent but for clarity we do not show this here. The depolarisation ratio \( p_{0} \left( \lambda \right) \) is the ratio of horizontally to vertically polarised light scattered into the perpendicular observation direction for an unpolarised laser beam. The last term in brackets in Eq. 10 is often called the King Correction Factor, \( F_{K} \) [35]. For this work, the probe laser propagates along the y-axis, is polarised along the z-axis and scattered light is collected at 90° along the x-axis. This is shown schematically in Fig. 15. Under these conditions the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section—i.e., the scattering cross-section per unit solid angle is given by:

Leading to

To simplify and remove the density dependence \( N \), we make use of the molar refractivity \( R_{L} \left( \lambda \right) \) [36] (with units of cm3·mol−1) given by:

where \( \rho \) is the molar density \( N/N_{A} \) in units of mol·cm−3 at the pressure and temperature at which \( n\left( \lambda \right) \) is measured. Substituting Eq. 14 into Eq. 13 gives a simplified working equation:

It is important to re-iterate that \( p_{0} \left( \lambda \right) \) is the depolarisation ratio for an unpolarised probe beam and that \( d\sigma /d\Omega \left(\uplambda \right) \) is the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section for a linearly polarised probe beam measured perpendicular to both the probe beam’s direction and polarisation. In this work, we use a probe beam operating at \( \lambda \) = 532 nm. Values for \( R_{L} \) and \( p_{0} \) at this wavelength and STP conditions (0 °C, 1 atm.) are tabulated in [36, 37], respectively, for all significant hydrocarbon/air combustion products. Together with the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section, these are tabulated in Table 1.

The OH radical has been omitted from this study, since at chemical equilibrium it amounts to approximately 0.3 % by mole fraction, and calculations show that the net contribution to the Rayleigh scattering cross-section amounts to at most 0.1 % (and significantly less either side of stoichiometric). It is worthy of note that other flame radicals such as NO and H have significantly smaller scattering cross-sections than OH and tend to counterbalance the small rise in cross-section from OH.

The molar refractivity for air is a special case and is needed to determine the difference in the scattering cross-section of the combustion gases relative to that of air, where an initial calibration measurement is made at known temperature. Table 2 shows how this is obtained from the mole fraction weighted sum of \( R_{L} \) for the major species present in air.

By making use of Eq. 15 and Table 1, the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section can be calculated for air and any relevant combustion species at STP conditions.

1.3 Determination of \( \delta \)

1.3.1 Definition: Equivalence Ratio \( \phi \)

For any combustion reaction, the equivalence ratio is defined as the ratio of the volume of fuel to the volume of air (oxidiser) divided by the same ratio for stoichiometric conditions

Stoichiometric conditions occur when the ratio of fuel to air is such that there is no excess oxygen after combustion, so a value of \( \phi = 1 \) corresponds to complete balanced combustion and generally produces close to the maximum post-flame temperature. For the propane fuel used in this work, when \( \phi \) = 1, \( V_{fuel} /V_{air} \) = 0.0419, i.e., the volume of fuel burned is 4.19 % the volume of the air consumed.

To calculate the flame temperature \( T_{2} \), the value of \( \delta \) must be determined and although the value of \( \left( {d\sigma /d\Omega } \right)_{air} \) is known (and can be taken from Table 1), the value of \( \left( {d\sigma /d\Omega } \right)_{f} \) depends strongly on the equivalence ratio \( \phi \) and weakly on \( T_{2} \). This leads to a difficulty in solving Eqs. 8, 9. A strategy developed to overcome this difficultly follows.

Since the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section of the post-flame gas is given by the mole-fraction weighted sum of the individual scattering cross-sections of each species present, i.e., \( \left( {d\sigma /d\Omega } \right)_{f} = \sum\nolimits_{i} {X_{i} \left( {d\sigma /d\Omega } \right)_{i} } \), we need to determine the temperature dependence of each species separately and then combine the contributions. We can recast Eq. 15 by making use of Eq. 11 and the relationship between \( \alpha \) and \( R_{L} \) given by:

This leads to an expression that defines the differential Rayleigh scattering cross-section of species \( i \), in terms of \( \alpha_{i} \) and \( \gamma_{i} \) only:

Thus, the temperature dependence of \( \left( {d\sigma /d\Omega } \right)_{i} \) can be determined completely by finding the temperature dependence of \( \alpha_{i} \) and \( \gamma_{i} \). For small fractional increases in \( \alpha_{i} \) and \( \gamma_{i} \), given by \( \left( {\Delta \alpha_{i} /\alpha_{i} } \right) \) and \( \left( {\Delta \gamma_{i} /\gamma_{i} } \right) \), the absolute change in \( \left( {d\sigma /d\Omega } \right)_{i} \) can be written as:

By substituting in the partial derivatives, we arrive at the result:

The temperature dependence of \( \alpha \) for typical combustion species [38, 39] varies between 0.2 % and 1.4 % for a temperature rise of 1000 K, depending on species. In [38] the temperature dependence for Ar, O2, H2 and N2 is given over the limited temperature range 300 K to 1100 K. We fit a linear trend to this data, calculate the expected change due to a 1000 K temperature rise and assume that the trend will be the same at higher temperatures. In [39], the temperature dependence is given for N2, Ar, O2, CO2, CO, H2 and H2O for excitation wavelengths of 266 nm and 355 nm up 1525 K. We estimate the equivalent temperature dependence at 532 nm for this work by assuming a linear dependence with measurement wavelength.

The temperature dependence of the molecular anisotropy, \( \gamma \) has not been established experimentally. However, it is possible to use theoretical arguments to assess the appropriate trend. Ab initio calculations of the polarizability of \( H_{2} \) reveal a larger relative increase in the anisotropy than in the polarizability with increasing inter-nuclear distance [40]. For typical combustion species the increase is estimated to be of the order of 2 % per 1000 K rise in temperature. This seems reasonable since we see from Eq. 18 that the contribution to the differential scattering cross-section of the anisotropy term is weighted by a factor 7/45. An increase in the anisotropy of 2 %/ 1000 K is thus assumed for this work. The uncertainty in the flame temperature due to this approximation is less than ± 0.15 % [1].

Table 3 shows a summary of the calculated parameters needed to determine the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section at 532 nm for all significant combustion species at any temperature. The first six rows show the parameters used in the cross-section calculations, and the final four rows show results of these calculations. Row 7 shows the baseline scattering cross-sections for each species at 300 K and Rows 8, 9 and 10, respectively, show the fractional changes in \( \alpha_{i} \), \( \gamma_{i} \) and Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section per 1000 K temperature rise.

The procedure to calculate \( \delta \left( {\phi ,T_{2} } \right) \) is now described:

First, the Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section for all major combustion species over the possible range of flame temperatures is calculated. The temperature range of interest for propane/air combustion is {1600 K < T2 < 2400 K}. This is achieved by making use of Rows 7 and 10 in Table 3 as follows:

Table 4 shows a summary of these calculations.

Second, the equilibrium species concentrations for propane/air combustion over the full range of equivalence ratios and possible flame temperatures is calculated using chemical the equilibrium software GasEq [33]. The range over which calculations have been made are: \( \left\{ {0.5 < \phi < 2.0} \right\} \) and \( \left\{ {1600 {\text{K}} < T_{2} < 2400 {\text{K}} } \right\} \). The software provides an option to calculate the equilibrium mole-fraction species concentrations at a defined pressure and temperature and this is used here.

For the Hencken burner used in this work, a flame with a temperature of up to 10 % below the adiabatic flame temperature \( T_{ad} \) can be stabilized for \( \left\{ {0.7 < \phi < 1.4} \right\} \). Thus, the ranges over which the species concentrations have been calculated in both \( T_{2} \) and \( \phi \) are more than adequate. The adiabatic flame temperature is the maximum possible flame temperature achievable if there are no heat loses from the flame i.e., to the burner surface or radiated to its surroundings. This is never achieved in practice and is why we need to measure the flame temperature and not rely on calculations. Table 5 shows an example of these calculations for \( \phi = 1.0 \) and Fig. 16 shows the major and minor species concentrations versus \( \phi \) for \( T_{2} = T_{ad} \). The inlet gas temperature \( T_{0} \) is assumed to be 64 °C which was the mean burner surface temperature during operation and it is assumed that the gases acquire this temperature before they leave the burner.

Thirdly, the mole-fraction weighted Rayleigh differential scattering cross-section of the combustion gas at \( T_{2} \) is calculated and \( \delta \left( {\phi ,T_{2} } \right) \) determined using the following equations:

Table 6 and Fig. 17 show the value of \( \delta \left( {\phi ,T_{2} } \right) \) for the range of interest in this work and we see that it varies by up to 20 % with \( \phi \) (ranging from 0.97 when \( \phi \) = 2.0, to 1.17 when \( \phi \) = 1.0) and up to 3 % with \( T_{2} \). If we had assumed the scattering cross-section remained unchanged between the air calibration and flame measurements, the temperature could be in error by up to ≈ 17 %.

Finally, since \( T_{2} \) is close to \( T_{ad} \), we make an initial estimate of \( \delta \left( {\phi ,T_{2} } \right) \) by assuming \( T_{2} = T_{ad} \), where \( T_{ad} \) is calculated using the chemical equilibrium software GasEq [33].

1.4 Determination of \( T_{2} \)

To determine the post-flame temperature \( T_{2} \) we employ an iterative procedure:

- 1.

An initial estimate of the post-flame temperature is made using Eq. 8:

$$ \left\langle {T_{2} \left( 0 \right)} \right\rangle = \delta \left( {\phi , T_{ad} } \right)\frac{{S\left( {T_{1} } \right)}}{{S\left( {T_{2} } \right)}}T_{1} $$(24)where \( S\left( {T_{1} } \right) \) and \( S\left( {T_{2} } \right) \) are the Rayleigh scattering signals measured in air (calibration point) and the post-flame regions, respectively, and \( T_{1} \) is measured via a calibrated PT100 sensor.

- 2.

A new value of \( \delta \left( {\phi ,\left\langle {T_{2} \left( 0 \right)} \right\rangle } \right) \) is calculated.

- 3.

A new estimate of \( T_{2} \) is then calculated:

$$ \left\langle {T_{2} \left( {n + 1} \right)} \right\rangle = \delta \left( {\phi , \left\langle {T_{2} \left( n \right)} \right\rangle } \right)\frac{{S\left( {T_{1} } \right)}}{{S\left( {T_{2} } \right)}}T_{1} $$(25) - 4.

Steps 2 and 3 are repeated until convergence is achieved.

For a given \( \phi \), \( \delta \) is a monotonic decreasing function of \( T \) and only changes by at most 4 % over the full range of possible flame temperatures. For this reason, the iterative procedure described above converges to the true flame temperature quickly—within three iterations. The difference between \( \left\langle {T_{2} \left( 0 \right)} \right\rangle \) and \( \left\langle {T_{2} \left( 3 \right)} \right\rangle \) is at most 1 %, so it is necessary to iterate to obtain the required 0.5 % uncertainty but the change in \( T_{2} \) is not large.

Appendix B1: Uncertainty Budget—Rayleigh Scattering Thermometry (NPL)

Table 7 shows the uncertainty budget for the temperature measured 20 mm above the centre of the burner (\( R_{z} \) = 0 mm) using Rayleigh scattering Thermometry. For regions closer to the burner surface, where thermal and chemical equilibrium may not have been reached, and beyond ± 10 mm horizontally from the central position, where the gas composition is uncertain, the uncertainties will be significantly larger.

In accordance with the Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement [41], the Multiplier (column 5) is used to convert a rectangular uncertainty contribution (Type-B) into the equivalent normal uncertainty contribution and is equal to \( 1/\sqrt 3 \). The Sensitivity coefficient (column 6) describes how the output estimate (in this case flame temperature) varies with changes in the input estimate (i.e., it is the partial derivative of the output estimate with respect to the input estimate).

For example, considering the Flow-meter uncertainty(+)—this has a rectangular uncertainty distribution of ± 1 %, indicating that the indicated flow could be expected to be anywhere within ± 1 % of the true value. We convert this to the equivalent normal distribution my multiplying it by \( 1/\sqrt 3 \) giving ± 0.58 % and then by the sensitivity factor of 0.4 (determined by offsetting the propane flow by + 1 % and determining the new flame temperature) yielding an overall uncertainty of 0.23 % in flame temperature.

Appendix B2: Uncertainty Budget—Hyperspectral Imaging Thermometry (UC3M)

Uncertainty estimation has been divided in two parts [28]: (1) the uncertainty in the measured radiance, and (2) the propagation of this uncertainty into the retrieved values of temperature, \( T \) and species column density \( Q \), which determines the respective sensitivity coefficients. This approach is essentially the same as that in [32]. This second stage has been carried out by Monte Carlo simulation of a large number of noisy spectra, representative of the experimental conditions, and the associated noise in the calculated \( \left( {T,Q} \right) \) values. The uncertainty in the measured radiance has two main sources: calibration errors and measurement errors. Their values are estimated, respectively, by the uncertainties in emissivity and temperature of the references used for calibration, propagated to obtain a spectral standard deviation σc(ν) due to calibration for the radiance of the measured spectra, and by the Noise Equivalent Spectral Radiance of the measurement system (which was found to be negligible compared to σc). Additional uncertainties in spectral radiance are included to take into account the reproducibility of measurements and the typical fitting errors, to obtain a total spectral variance \( \sigma_{i}^{2} \left( \nu \right) \) of radiance. Then the Monte Carlo simulation is applied, constructed from a theoretical spectrum \( L_{0} \left( \nu \right) \), a population of 1000 spectra, whose average and variance are \( L_{0} \left( \nu \right) \) and \( \sigma_{i}^{2} \left( \nu \right) \) respectively. The default spectrum corresponded to \( T \) = 2000 K, \( Q_{{CO_{2} }} \) = 1000 ppm·m, and \( Q_{CO} \) = 200 ppm·m. Applying these calculations, and taking into account uncertainties in the HITEMP2010 database, leads to uncertainty estimates of ± 5 K for temperature, ± 10 ppm·m for CO2 column density and ± 1 ppm·m for CO column density. Table 8 summarizes the error budget.

Appendix B3: Uncertainty Budget—FTIR Thermometry (DTU)

The reproducibility of the DTU emission spectra measurements in 1800–2500 cm−1 and 3000–4200 cm−1 is less than 2 % and 5 % respectively, for time spans from minutes to days. The source of this variability is a combination of variation in both species (CO2/H2O) and flame temperature. It should be noted that emission intensity in the range 3000–4200 cm−1 is approximately seven times smaller than that in the range 1800–2500 cm−1. Considering 2 % as a maximum scaling factor, overall reproducibility in the 1800–2500 cm−1 range is better than 0.5 %. Uncertainty in the FTIR stability over a single measurement is 0.1 %. Uncertainty in black body calibration is 0.2 %. Quality of the HITEMP2010 database is 0.17 % in 2150–2500 cm−1 (this range has the most “weight” in the retrievals). Therefore, overall uncertainty in the temperature profiles retrievals from forward Radiative heat transfer (RHT) calculations (Eq. 5) is approximately 0.2 %. Table 9 summarizes the error budget.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sutton, G., Fateev, A., Rodríguez-Conejo, M.A. et al. Validation of Emission Spectroscopy Gas Temperature Measurements Using a Standard Flame Traceable to the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90). Int J Thermophys 40, 99 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-019-2557-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-019-2557-6