Abstract

Few studies of post-Columbian animal economies in the Americas elaborate on the influence of traditional Indigenous knowledge on colonial economies. A vertebrate collection from Santa Elena (1566–87 CE, South Carolina, USA), the original Spanish capital of La Florida, offers the opportunity to examine that influence at the first European-sponsored capital north of Mexico. Santa Elena’s animal economy was the product of dynamic interactions among multiple actors, merging preexisting traditional Indigenous practices, particularly traditional fishing practices, with Eurasian animal husbandry to produce a new cultural form. A suite of wild vertebrates long used by Indigenous Americans living on the southeastern North Atlantic coast contributes 87% of Santa Elena’s noncommensal individuals and 63% of the noncommensal biomass. Examples of this strategy are found in vertebrate collections from subsequent Spanish and British settlements. This suggests the extent to which colonists at the Spanish-sponsored colony adopted some Indigenous animal-use practices, especially those related to fishing, and the speed with which this occurred. The new cultural form persisted into the nineteenth century and continues to characterize local cuisines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

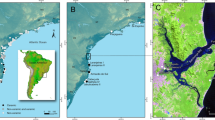

Archaeologists and others have long been interested in the causes and consequences of interactions among different cultures in distinct economic, geographical, political, and temporal settings (e.g., Beaule 2017; Campana et al. 2010; Crabtree and Ryan 1991; Lyons and Papadopoulos 2002; Mondini et al. 2004; Stein 2005). Interactions after 1492 CE in the Americas are of particular interest because they are relatively recent, their multifaceted impacts on Native peoples and ecosystems were profound, and the consequences persist (e.g., Becker 2013; Braund 1993; Deagan 2004; Gonzalez and Panich 2021; Gremillion 2002b; Jones 2016; Kelly and Hardy 2011; Lapham 2005; Larsen et al. 2001; Marcoux 2010; Mrozowski et al. 2008; Perttula 2010; Thomas 1990; Usner 1992; VanDerwarker et al. 2013; Waselkov 2004; Wesson and Rees 2002). Zooarchaeological studies elaborate on the extent to which animals were involved in these outcomes (e.g., deFrance 1999, 2003; deFrance and Hanson 2008; deFrance et al. 2016; Gifford-Gonzalez and Sunseri 2007; Grimstead and Pavao-Zuckerman 2016; Noe 2022; Pavao-Zuckerman and LaMotta 2007; Peres 2022; Sunseri 2017). The goal of this paper is to demonstrate the extent to which traditional Indigenous animal economies might influence a colonial animal economy, the speed with which this might occur, and the persistence of the new cultural form using data from Santa Elena (38BU51/38BU162, South Carolina, USA). Santa Elena was the first European-sponsored capital north of Mexico and the first capital of Spanish La Florida (Fig. 1).

Map of La Florida and the Georgia Bight with present-day place names. See Table 1 for information about each site (prepared by Evan Cizler)

Much of the literature about post-Columbian consequences focuses on definitions of terms such as acculturation, colonialism, colonization, creolization, cultural entanglement, ethnogenesis, hybridity, mestizaje, power dynamics, resilience, symmetrical exchange, and syncretism, among others (e.g., Cusick 1998; Deagan 1973, 1983, 1990; Dietler 2010: 47–53; Jordan 2009; Joseph and Zierden 2002; Lightfoot et al. 2013; Silliman 2001, 2020; Voss 2008, 2015). These terms capture subtle differences in the cultural, economic, environmental, and political contexts of each interaction and the diverse outcomes. Many of these studies focus on the influence of colonizers on Indigenous populations, often tracing the outcome in a more or less linear fashion back to the sponsoring nation or the origins of the colonists.

Although most studies acknowledge that colonizers quickly adopted some Indigenous American cultigens, such as maize (Zea mays) and squashes (Cucurbita spp.), the prevailing assumption is that European and African practices prevailed with few, if any, changes while Indigenous practices were altered or abandoned. The influence of local practices on colonists is less frequently considered (Twiss 2020). It is particularly unusual for studies to elaborate on the influence of traditional Indigenous knowledge on the animal economies of the colonists themselves (for exceptions see Clute and Waselkov [2002]; Panich et al. [2021]; Rodríguez-Alegría [2005]; Scott [2007]; Senatore [2022]; Silvia [2002]).

Deagan (1998: 23, 25) argues that new cultural forms with “multiple origins and multiple active agents” emerge in colonial settings. These new cultural forms combine traditions through what may be described as entanglement and transformation (Dietler 2010: 12, 18, 55–56). We define new cultural forms as ones that include both Indigenous traditions and practices as well as those of colonists into new traditions and practices. Thus, we approach the animal economy at Santa Elena from the perspective that “all parties to colonial encounters are transformed by the process” (Dietler 2010: 336), giving particular emphasis to the role of traditional Indigenous practices in the new cultural form.

This perspective is consistent with archaeobotanical and material culture studies of Indigenous American, Eurasian, and African experiences in the southeastern United States. These studies document diverse responses to post-Columbian economic, political, and social forces that drew upon both Indigenous and immigrant traditions (e.g., Gremillion 2002a; Hardy 2011; Pavao-Zuckerman and Loren 2012). Zooarchaeological studies, in particular, demonstrate that Indigenous animal economies merged with colonists’ traditions of animal husbandry to form new economic strategies with local variations (e.g., Orr and Lucas 2007; Pavao-Zuckerman 2000, 2007; Pavao-Zuckerman and Reitz 2011; Reitz 1994; Reitz et al. 1985; Reitz and Waselkov 2015; Scott and Dawdy 2011). These new cultural forms cannot be attributed entirely to African, Eurasian, or Indigenous American origins and involved active participation of both Indigenous communities and colonists.

La Florida (see Fig. 1) is a particularly important example because it was the first sustained European-sponsored settlement on the North American Atlantic seaboard (Deagan 1990). This Spanish-sponsored colony was established in 1565, decades before French-sponsored settlements in New France (1608) and British-sponsored settlements in Virginia (Jamestown, 1607), Massachusetts (Plymouth, 1620), and South Carolina (Charles Town, 1670). La Florida was a royal province whose governor was responsible to the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and the Spanish monarch. It was a culturally diverse province where ideas and practices were exchanged among Indigenous Americans (including those from elsewhere in the Spanish Empire), immigrants from Europe, Africa, and, probably, Asia to form new economic, political, and social institutions (Deagan 1990). Archaeological studies of European and African sites show that economic activities in La Florida were altered to reflect these new conditions. Likewise, Native communities modified their economies to incorporate new resources, though it appears early colonists’ strategies changed more than did those of Indigenous Americans (e.g., Reitz 1993; Reitz et al. 2010). This new cultural form is particularly evident in colonial fisheries, exemplified by the vertebrate collection from Santa Elena.

Zooarchaeological data from Santa Elena, founded in 1566, show the extent to which early colonizers merged Indigenous practices with animal husbandry and the speed with which that occurred. We begin by reviewing the history of La Florida and Santa Elena. We then describe a pre-Columbian baseline assemblage constructed from zooarchaeological studies of the pre-Columbian Indigenous economy, particularly the fishery. This is followed by a review of the zooarchaeological evidence from Santa Elena with reference to the baseline assemblage. Vertebrate collections from subsequent Spanish, British, and American sites indicate that characteristics of this new tradition persisted into the late 1800s, documenting the strength of the new cultural form (see Table 1).

A Brief History of Spanish La Florida and Santa Elena

Colonists and Indigenous Americans interacted far beyond the Atlantic coast (e.g., Beck et al. 2017; Pavao-Zuckerman 2007), but the focus of our study is a biogeographical province known as the Georgia Bight, a coastal region between Cape Fear and Cape Canaveral (Fig. 1). The Bight is characterized by an outer band of barrier islands, behind which lies a complex web of salt marshes, tidal creeks, marsh islands, and sounds, locally referred to as estuaries (Fig. 2). Estuaries are nurseries and feeding areas for marine, endemic, and freshwater organisms used by Indigenous communities for millennia (e.g., Reitz 2021). A broad continental shelf extends eastward from the seaward side of the barrier islands; the nearshore shallow portion is referred to as inshore and the deeper waters are referred to as offshore. Estuaries serve an important nursery role for many marine species, including some which enter estuaries only to spawn. Other species live most of their lives in estuaries, though some of these may leave them seasonally to spawn on the continental shelf. The land bordering the Georgia Bight is characterized by low-lying forests, freshwater and brackish streams, swamps, and marshes referred to as the “Lowcountry.” Lowcountry streams are subject to tidal influence as much as 30–60 km inland from the coast.

For sake of simplicity, several terminological conventions are followed. Locations are referred to in terms of their current geopolitical affiliation. Thus, Santa Elena is said to be in the State of South Carolina, in the United States of America (USA). Sites are referred to in terms of their major European claimants. These were the Spanish Empire, or entities that had been or were to become part of that empire (e.g., the Philippines, the Netherlands, Germany, northern Africa, New Spain, the Canary and Caribbean islands), England (not becoming Great Britain until 1707), and France. Spanish, and British colonies were multiethnic communities despite their designation as “Spanish” or “British” (Dunkle 1958; Ewen 2009; Joseph and Zierden 2002; Lyon 1976; TePaske 1964). La Florida included people from the vast Spanish Empire, other Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous Americans from the Southeast as well as elsewhere in the Americas (e.g., Deagan 1983: 9–46; Landers 1990). These are all referred to as “Spanish” because of their affiliation with the Spanish Empire; not because they were born in Spain (termed peninsulares) or had a Spanish heritage (termed criollos). In this context, Africans are considered colonists, though for many Africans this was not by choice.

The North American Atlantic seaboard appears on maps as early as 1502 (Hoffman 1990: 3, 60, 58, 91, 158). Thereafter, southeastern Natives experienced numerous authorized and unauthorized expeditions and settlements. The first formal Spanish entrada was by Juan Ponce de León in 1513. This was followed by Pedro de Quejo’s slaving expeditions and explorations in 1521 and Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón’s attempt to establish San Miguel de Gualdape in 1526, first on the South Carolina coast and then on the Georgia coast (Hoffman 1990: 60–62). Pánfilo de Narváez’s attempt to establish a colony on the northern Gulf of Mexico in 1527 was followed by Hernando de Soto’s exploration of the Southeast (1539–43) and Tristan de Luna’s attempt to establish a colony on the northern Gulf coast in 1559. In 1562, France sponsored the construction of Charlesfort on Parris Island (see Fig. 1). This settlement was abandoned in 1563. Another French settlement (Fort Caroline) was built at the mouth of the St. Johns River in 1564.

Alarmed by French initiatives, King Philip II of Spain entered into a joint venture with Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to establish a settlement on the Atlantic coast. Menéndez became the first governor of La Florida, agreeing to advance commerce and defense by establishing two or three towns, among other commitments (Hoffman 1990: 251–261; Lyon 1976: 48–53). St. Augustine was founded in 1565, becoming the first permanent European-sponsored town north of Mexico. After destroying Fort Caroline, Menéndez established his second town, Santa Elena, on Parris Island in 1566. Santa Elena was designated the capital because of its deep-water port and strategic advantages (Lyon 1976: 42–43, 156–157). It was here that Menéndez settled his family.

Menéndez was accompanied by more than a thousand people when he left Spain, though only 600–800 remained when he reached Florida (e.g., Deagan 1980: 23, 1983: 22–23; Dunkle 1958; Lyon 1984). Additional colonists were recruited in Puerto Rico to replace those who had deserted or been lost (Lyon 1976: 104). Twenty-six of the men who sailed from Spain brought wives and children (Lyon 1976: 92). The population of La Florida fluctuated dramatically throughout the period and it is difficult to determine how many people lived at Santa Elena or to distinguish among missionaries, sailors, soldiers, farmers, other settlers, prisoners of war, and enslaved people. In 1569, 273 new settlers reached La Florida, 193 of whom went to Santa Elena (Lyon 1981: 285, 1984: 4). By the end of 1569, 327 people lived there and there were 40 houses (Lyon 1981: 285; 1984: 4). There were between 45 and 60 farmers at Santa Elena in 1573 (Connor 1925: 82/83, 92/93). In 1580, there were 60 houses (Lyon 1984: 13). Although the first settlers in La Florida largely originated in Asturias, Santander, Estremadura, and Andalucia. People from England, France, Germany, Portugal, and Indigenous Americans also were present, as were Africans, some of whom were enslaved (Deagan 2003: 5; Dunkle 1958; Lyon 1976: 75; 1978: 24–25).

Colonists included families, people skilled in trades and crafts, priests, farmers, administrative personnel, soldiers, and sailors (Lyon 1976: 92; 1978). Many served both as soldiers and in private commercial roles. These roles included barber surgeon, bellows maker, boarding house operator, carpenter, drummer/crier, hunter, fisherman, stock raiser, notary, pilot, sawyer, shield maker, tailor, blacksmith, cobbler, tavern keeper, pitch maker, match-cord maker, charcoal burner, and Indian trader (Lyon 1978: 23). Over time, however, most residents were soldiers. Colonists cleared and drained land; encouraged Eurasian livestock and plants; exported furs, hides, timber, sarsaparilla, and other forest products; and displaced Indigenous communities. Unlike earlier Spanish colonies, by the time La Florida was founded, the encomienda system was no longer permitted (Deagan 1983: 22).

It seems likely that some of the people living at Santa Elena were Indigenous women, as well as enslaved Indigenous peoples and Africans. St. Augustine households included Indigenous women as wives, concubines, and servants (Deagan 1973, 1983: 103–104, 2003: 7–8; Paar 1999: 88–128). Marriages invariably involved Indigenous women and non-Indigenous men, a relationship which undoubtedly influenced foodways and technology in the colony (Deagan 1983: 104, 234). This likely was the case in both St. Augustine and Santa Elena. At one point, ca. 30% of the households in St. Augustine included women and ca. 50% of these women were Spanish; the other women being Indigenous (Deagan 1980: 28; Manucy 1985). Both Africans and Indigenous Americans could be enslaved; some enslaved Indigenous Americans were from inland locations (Lyon 1984: 8, 21).

Several tribes interacted with colonists, particularly those known today as Escamazu, Guale, and Orista. Indigenous peoples were expected to pay tribute to the crown and tithes to the church, often doing so in kind. Many of these exchanges were contentious, including those involving trade, tribute payments, and tithes (e.g., Lyon 1984: 7, 9).

Civil unrest, diseases, raids by French and British forces, Indigenous resistance, and natural disasters contributed to shortages of imported staples, munitions, fabrics, and other materials, hampering efforts to develop a self-sufficient European-style economy (e.g., Connor 1925, 1930; Lyon 1976, 1984). An official subsidy, or situado, was established in 1571 to resolve the supply problem, with mixed results (Bushnell 1981; Deagan 1983: 34–39; Sluiter 1985). The irregular arrival of imported goods encouraged colonists to rely on local resources throughout La Florida. Colonists reported that meat was scare and they ate oysters (Crassostrea virginiana), fish, herbs, and foods referred to as vermin (e.g., Arnade 1959: 30, 37; Bushnell 1981: 11; Connor 1925: 99; Lyon 1976: 166, 1984: 5).

In 1576, Santa Elena was abandoned in the face of stout opposition from local Indigenous Americans, and St. Augustine became the capital of La Florida. Santa Elena continued to be strategically important and was reoccupied in 1577. Spain abandoned Santa Elena a second time in 1587 to consolidate defensive forces in St. Augustine (Arnade 1959). Throughout this period, colonists were harassed by French and British activities along the coast and by Indigenous communities.

Spain originally claimed most of what became the eastern United States, though the functional size of La Florida was considerably smaller. For two centuries, Spanish cattle ranches, fortifications, missions, and settlements were built and abandoned along the Gulf of Mexico, across peninsular Florida, along the western Atlantic coast, and into the interior Southeast. Many of these outposts were short-lived as the Spanish presence was consolidated in St. Augustine in the face of advancing British interests after the 1670s, renewed French ones after the 1680s, and American ones after 1776 (e.g., Bolton and Ross 1968; Wright 1971). This process accelerated after Carolina Governor James B. Moore attacked the mission chain and St. Augustine in 1702 and 1704. Ironically he staged his forces on Parris Island, which had been in British hands since 1670. Spain relinquished what remained of La Florida to Britain in 1763, regained part of peninsular Florida in 1783, and yielded what remained of La Florida to American interests in 1821. Parris Island continues to have strategic importance; Santa Elena today lies beneath a golf course at the United States Marine Corps Recruit Depot.

Zooarchaeological Methods

The zooarchaeological study relies on taxonomic attributions, the number of identified specimens (NISP), estimates of the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI, sensu White 1953), biomass, richness, and diversity (H’) of vertebrate remains. For fish, mean trophic level (TL) is estimated. These methods are summarized here and discussed in more detail elsewhere (Reitz and Wing 2008: 110–113, 205–210, 223–224, 238–242, 245–247). Zooarchaeological attributions for all collections in this study were made using the comparative skeletal collections of the Zooarchaeology Laboratory at the Georgia Museum of Natural History or the Environmental Archaeology Program at the Florida Museum of Natural History following standardized procedures (Reitz and Wing 2008). Readers are reminded that outcomes for all zooarchaeological studies are influenced by anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic site formation processes, as well as biases associated with recovery methods, sample sizes, and the analytical procedures used to estimate taxonomic attributions, dietary contributions, and fishing methods, counseling conservative interpretation of the results.

Collections containing both artiodactyls and fish, such as those from the Georgia Bight, challenge efforts to assess the economic roles of these vertebrates. Fish often dominate NISP and estimates of MNI in Georgia Bight collections, especially those from periods prior to the eighteenth century. At the same time, artiodactyls (e.g., white-tailed deer [Odocoileus virginianus], pigs [Sus scrofa], cattle [Bos taurus]), may dominate biomass estimates in these same collections. Broadly speaking, MNI and biomass capture different aspects of animal economies, clarifying the distinct roles fishes and ungulates played in coastal economies. MNI suggests the relative abundance of different types of animals in a collection and biomass suggests which of these animals contributed most of the animal protein. Another way to approach this is to consider a week in which every meal included small catfish, but one of these meals included a large serving of venison. Thus fish MNI and deer biomass represent different aspects of the animal economy.

MNI estimates are based on symmetry, age at death, and size for each taxon (sensu White 1953) and biomass estimates are derived using the allometric equation:

where Y is the quantity of meat, X is the skeletal weight of the specimen, b is the constant of allometry (the slope of the line), and a is the Y-intercept for a log-log plot using the method of least squares regression and the best fit line.

Richness, ubiquity, diversity, and equitability are derived from taxonomic composition, MNI, and biomass. Richness is the number of taxa for which MNI is estimated. Ubiquity refers to the number of collections in which a taxon is present and for which an MNI estimate is available. Diversity is estimated using the Shannon-Weaver Index:

where pi is the number of the ith species divided by the sample size (Shannon and Weaver 1949: 14). Pi is the evenness component because the Shannon-Weaver Index measures both how many species were used and how much each was used. Diversity increases as the number of species increase. Equitability is estimated using the formula:

where H’ is the Diversity Index and LogeS is the natural log of the number of observed species (Sheldon 1969). Equitability values approaching 1.0 indicate an even distribution of taxa and low values suggest that only a few taxa dominate the studied collection.

Mean trophic level (TL) quantifies the relative abundance of low-trophic-level vegetarian and omnivorous fishes compared to high-trophic-level carnivores. TL is estimated using the formula:

and trophic levels in FishBase98 (Froese and Pauly 1998) following the methods of Pauly and Christensen (1995) adapted by Reitz (2004). Minor changes in trophic level assessments are frequent in FishBase, therefore TL values from FishBase98 are used to maintain consistency with previously published TL estimates (Froese and Pauly 1998). When zooarchaeological attributions and/or FishBase98 are imprecise, the trophic level for the closest taxonomic category is used. Freshwater fishes are not included in FishBase98 and values in FishBase 2022 (www.fishbase.org) are used.

Vertebrate trophic levels range from a low of 2.1 to a high of 5.0. Fishes feeding at lower trophic levels, primarily herbivores and detritivores, are more abundant than carnivores in a healthy ecosystem. Low-trophic-level fish likely require less time and effort to capture because they are more common and the risk of failure may also be low for the same reason. On the other hand, high-trophic-level carnivorous fish often are more expensive and more prestigious because they are less common and difficult to capture. Broadly speaking, reliance on TL levels over 3.4 or 3.5 may be unsustainable. Human fishing effort, technology, and yield reflect the relative abundance and accessibility of these fish. Decisions about which fishing technologies and which fish to use influence exchange systems, labor management, political events, and social relationships.

A logged ratio diagram is used to assess transportation biases and differential access to portions of pig and deer carcasses in the Santa Elena collection (Simpson 1941). This permits NISP for groups of elements recovered from Santa Elena to be compared to those same groups in a complete, unmodified pig or deer skeleton. The formula is:

where d is the logged ratio, X is percentage of that element category in the archaeological sample, and Y is percentage of that element category in the standard deer. The resulting value (d) is plotted against the standard skeleton represented by a vertical line. The closer a bar is to the center line, the more likely the element group represented by that bar is what one would expect if the entire carcass/skeleton was present. Bars on the positive side of the scale are overrepresented compared to the standard skeleton and those on the negative side are underrepresented. This approach compensates for the fact that pigs have more elements than do deer by comparing pig NISP with the NISP of a complete pig skeleton and deer NISP with that of a complete deer skeleton.

Commensal animals are those that might be consumed, but that also may be associated with people and their built environment as pets, work animals, and vermin, or as part of the surrounding wildlife (Reitz and Wing 2008: 137–138). Some commensal animals are ones that people either do not encourage or actively discourage. Animals classified as commensal in this study are UID Frog/Toad, spadefoot toads (Scaphiopus holbrookii), toads (Anaxyrus spp.), lizards (Lacertilia), green anoles (Anolis carolinensis), UID Snake, nonpoisonous snakes (Colubridae), shrews (Soricidae; Blarina brevicauda), eastern moles (Scalopus aquaticus), mice, rats, and voles (Cricetidae), marsh rice rats (Oryzomys palustris), Hispid cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus), house mice (Mus musculus), Old World rats (Rattus spp.), canids (Canis spp., C. familiaris), and domestic cats (Felis catus). House mice, Old World rats, and domestic cats were brought to the Americas after 1492. Some of the animals included in the commensal category might have been consumed and some of the animals interpreted as noncommensal may have been commensal.

Invertebrates are excluded from this study, limiting evidence for this important aspect of life in the town. Oysters, in particular, are common in Santa Elena’s matrix and undoubtedly were important in the cuisine. Oysters also were used as building material and fill. Distinguishing among food waste, production waste, construction material, and drainage enhancements is difficult for vertebrates and even more challenging for invertebrates, assuming such a distinction existed in the first place. It is likely that oysters, other molluscs, crabs, and shrimp were important in both Indigenous and colonial fisheries.

The Pre-Columbian Baseline Assemblage

By the sixteenth century, people had lived along the Georgia Bight more than 4,000 years. Archaeobotanical data are limited for the region, though by the sixteenth century Indigenous American practices included farming. From the Spanish perspective, maize was a particularly important cultigen.

Zooarchaeological data offers a complex record of change, continuity, and diversity in coastal ecosystems and cultural systems (Quitmyer and Reitz 2006; Reitz et al. 2022; Reitz and Quitmyer 1988; Reitz et al. 2009). A chronological study of the 22 coastal vertebrate collections from sites lying between Charleston and St. Augustine suggests fisheries in the Georgia Bight were more strongly influenced by site location and site function than by chronology, though changes in coastal configurations and estuarine attributes over time likely strongly influenced site location (Reitz 2021). It is because of the similarity of individual collections to the overall pre-Columbian Georgia Bight pattern that we feel justified in merging data from these 22 zooarchaeological collections into a single pre-Columbian baseline assemblage. The baseline vertebrate assemblage contains 484,497 specimens representing an estimated 12,316 individuals from 207 taxa. The faunal collections used to build the baseline assemblage were studied using the same methods applied to the Santa Elena collection.

Although the baseline assemblage provides a useful pre-Columbian template for assessing the extent to which animal use at Santa Elena followed Indigenous traditions, merging data from individual sites into a single regional assemblage does not do justice to the variety of strategies practiced throughout the region. Faunal collections from Bourbon Field and Meeting House Field (late component) are included in Fig. 3 as examples of some of the variation that characterizes pre-Columbian coastal fisheries (see Table 1; Bergh 2012: 128–129; Reitz 1982, 2021).

Summary of the minimum number of Individuals (MNI) and biomass for domestic animals, deer, other wild vertebrates, and fishes at Georgia Bight sites discussed in the text (see Table 1 for information about each site)

Fish contribute 42% of the 207 vertebrate taxa in the baseline assemblage (Reitz 2021). The other taxa are reptiles (18% of the taxa), mammals (16%), birds (15%), and amphibians (9%). The role of deer is highly variable. Deer are present in 91% of the collections in the baseline assemblage, though they contribute less than 2% of the 12,316 vertebrate individuals in the assemblage (e.g., Reitz et al. 2022). The average MNI diversity for collections in the baseline assemblage is 2.561 and the average biomass diversity is 2.254 (Table 2). Oysters comprise over 60% of the individuals in each of the six collections for which systematically quantified vertebrates and invertebrates are both reported (Reitz et al. 2022).

Prior to 1500 CE, people relied heavily upon many of the same estuarine fishes prominent in Georgia Bight estuaries today (Reitz 2021). The most ubiquitous fishes in the baseline assemblage are typical of Georgia Bight estuaries and are characterized by flexibility and resilience (Reitz 2021; Reitz et al. 2012, 2022). For example, seatrout (Cynoscion spp.), one of the most abundant fish in estuaries today, has a ubiquity of 100% in the baseline assemblage (Reitz 2021). Other fishes present in at least 77% of the archaeological collections in the baseline assemblage are gars (Lepisosteus spp.), herrings (Clupeidae), sea catfishes (Ariidae, including hardhead catfishes [Ariopsis felis], gafftopsail catfishes [Bagre marinus]), mullets (Mugil spp.), silver perches (Bairdiella chrysoura), spots (Leiostomus xanthurus), croakers (Micropogonias undulatus), black drums (Pogonias cromis), star drums (Stellifer lanceolatus), and flounders (Paralichthys spp.). The nursery function of estuaries means that smaller, younger members of some species migrate out of estuaries as they mature, returning as larger adults to reproduce and feed.

Many of these fish can be taken in large quantities from several locations within estuaries using a variety of techniques throughout the year. The feeding behavior, average size, and/or tendency to form large aggregations of some of these taxa make them particularly susceptible to mass-capture technologies such as weirs and seine nets that benefit from, or even require, organized labor. Thirty of the 86 taxa in the baseline assemblage (35%) are particularly vulnerable to mass capture technology (e.g., Reitz et al. 2009, 2010: 236–237, 2022). This is especially true of the taxa with the highest ubiquity; those present in 95–100% of the collections in the baseline assemblage (sea catfishes, mullets, seatrouts, croakers). These taxa also are typical of estuaries and particularly likely to follow the incoming tide into small tidal creeks, which makes them susceptible to facilities that block tidal creeks on the outgoing tide.

Animals associated with offshore reaches, such as kingfishes (Menticirrhus spp.), are rare in the baseline assemblage (Reitz 2021). Young sea basses (Centropristis spp., also known as blackfish) are present in estuaries, but the larger adults are more abundant in the deeper waters of the continental shelf. Only one sea bass specimen (NISP) is present in any Georgia Bight collection. This specimen is from a site on the seaward side of St. Catherines Island occupied ca. 1300–1580 CE (9Li1637; Bergh 2012: 145–146). Snappers (Lutjanidae), which prefer warm tropical waters and reefs, are extremely rare in Georgia Bight estuaries (Dahlberg 1975: 65) and are not present in the baseline assemblage (Reitz 2021).

Although few animals other than oysters, fishes, and deer contributed substantially to the Indigenous animal economy in the Georgia Bight before 1565, many other vertebrates are present in the baseline assemblage (e.g., Reitz et al. 2022). Diamondback terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin), common in estuarine marshes, are present in 77% of the collections in the baseline assemblage and often are the most abundant turtle in these collections. Raccoons (Procyon lotor) also are present in 77% of the collections in the baseline assemblage.

Most of the 207 vertebrate taxa in the baseline assemblage are present in fewer than 77% of the collections. Among these are fresh or brackish-water turtles (Emydidae, other than diamondback terrapins), as well as snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) and mud or musk turtles (Kinosternidae). Lowcountry forests, wetlands, and streams also offer prime habitat for opossums (Didelphis virginiana), squirrels (Sciurus spp.), rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), woodrats (Neotoma floridana), bears (Ursus americanus), river otters (Lontra canadensis), minks (Neovison vison), and turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo). Turkeys are indigenous to the region (Thornton et al. 2021). Birds generally, however, are present in only a few collections, though rails (Rallidae) are present in 41% of the collections and ducks (Anatidae) in 27%. Many of these low ubiquity animals frequent salt marshes and estuarine waters. Dogs (Canis familiaris) are the only clearly domestic animal in the baseline assemblage.

Santa Elena: The Archaeological Site

Although people have occupied Parris Island for more than four millennia, most archaeological research focuses on the 1566–87 period associated with Santa Elena (38BU51/38BU162; DePratter and South 1995; South 1980, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985; South and DePratter 1996: 8–17, 129–132; Thompson et al. 2018). Santa Elena encompasses roughly 6 ha (DePratter and South 1995: 88). Excavations clustered between two forts, though the occupation covered the entire six ha. Figure 4 shows the portion of the site where the samples used in this paper originated. Indigenous ceramic types associated with the late-Prehispanic (Irene) and Hispanic (Altamaha) periods also are found in this area. The presence of Indigenous ceramics may not mean Indigenous Americans lived within the town because colonists throughout La Florida used Indigenous wares (e.g., Deagan 1983, 2003; DePratter 2009).

The Santa Elena materials reported here are from trash-filled pits dating to the 1580–87 period, the second period of occupation. These were excavated between 1979 and 1997 in excavation blocks C, D, L, M, N, and R under the direction of Stanley South and Chester DePratter. Faunal remains were recovered from these pits using 6.35-mm and 3.18-mm-meshed screens. House Lots 3 and 4 contain evidence of a large Spanish structure (#7). Gutierre de Miranda, the captain and governor of Fort San Marcos, occupied Lots 3 and 4 between 1580 and 1587 and had a hog farm and cattle ranch nearby (Lyon 1984: 13–14). This may have been his primary residence. Structure 1 was the residence of a servant or enslaved person, Structures 4 and 5 were outbuildings associated with Structure 7, and Structure 3 may not have been a structure at all (DePratter and South 1995: 8, 17, 81, 85).

Due to the large sizes of Lots 3 and 4, excavations as well as the vertebrate samples were subdivided into eight activity areas, with minimum number of individuals (MNI) and biomass estimated for each activity area. Faunal results from these activity areas are merged in Table 3. Readers are referred to Reitz (2017) for details of faunal remains from each activity area. Some faunal data reported here are revised from earlier reports (Reitz 1982, 1983; Reitz and Scarry 1985; South 1982, 1983; Weinand 1996). Data from 38BU162A, the forts (38BU162G, 38BU162H), and a kiln (38BU51D) are not included in this study.

A total of 90,179 vertebrate specimens containing the remains of an estimated 888 individuals from 96 taxa are present in the Santa Elena collection (see Table 3). This collection is similar to that from other parts of Santa Elena not reported here, including Fort San Felipe (Reitz and Scarry 1985). Sharks, rays, and bony fishes contribute 67% of the individuals and 25% of the biomass for taxa for which MNI is estimated (Table 4). Vertebrate use at Santa Elena falls within the diversity and mean trophic level ranges summarized by the baseline assemblage of local traditional Indigenous practices (Table 5 and see Table 2). The primary difference is the average MNI diversity, which is much higher in the Santa Elena collection. This likely is due to the large number of commensal individuals (5% of the MNI) in the Santa Elena collection. In every case, however, the derived values are within the baseline ranges.

Santa Elena’s Fishery

The Santa Elena collection clearly documents the significance of estuarine fishes in the town’s animal economy (see Tables 3 and 4). This rich collection is dominated by higher-trophic-level sea catfishes and drums. Hardhead catfishes are the most abundant vertebrate individuals (MNI). Sharks (Chondrichthyes), hardhead catfishes, black drums, and red drums (Sciaenops ocellatus) contribute most of the fish biomass. The mean trophic level of fish MNI in the Santa Elena collection is at the high end of the baseline MNI and biomass ranges, consistent with a catch containing large numbers of sea catfishes, drums, sheepsheads (Archosargus probatocephalus), and mullets.

Fish diversity suggests the fishery relied on methods that would capture many individuals of a few species and some individuals of many other species, characteristics associated with mass-capture technologies (see Table 5). The majority of the fish used at Santa Elena frequent estuarine waters and could be taken with methods similar to those used to catch these same fish species before 1565 (Reitz et al. 2022). These fish follow tides into and out of tidal creeks and would be particularly vulnerable to weirs, nets, wickerwork barriers, or canoes blocking creeks on the outgoing tide. Generalized mass-capture devices were described by John Ribault in 1562 (in Hakluyt 1966: 86–87; see also Bennett 1975: 20) and were used by both Indigenous fishers and colonists thereafter (García 1902: 202; Hann 2001: 72). Seine nets could be used to encircle fish. Although nets might be challenging to maneuver among shallow oyster bars, they could easily be used on beaches. Both small dragnets and casting nets are listed among inventories of fishing equipment in Florida between 1565 and 1569 and an inventory of the Menéndez household in Santa Elena includes lead weights for fish nets (Lyon 1992: 11, 21). Such mass-capture devices contribute 10 of the 37 fish taxa (27%).

Hand-line fishing also is suggested, particularly for sheepsheads and fast-swimming, carnivorous sharks, bluefishes (Pomatomus saltatrix), and jacks (Carangidae), as well as large drums. The time required to use handheld lines suggests that untended trot lines were used more frequently. Handheld lines might also expose colonists to enemy fire for a longer period of time.

Mullets contribute very few individuals in the Santa Elena collection, in sharp contrast to their prominence in the sixteenth-century St. Augustine collection where they contribute 33% of the noncommensal MNI. Mullets elude tidal weirs by leaping over them but are taken in large numbers with cast nets (e.g., Hann 2001: 72). The low numbers of mullets suggest cast nets seldom were used at Santa Elena but that some mullets were captured by other means. Mullets may also be less common in Port Royal Sound than they are further south.

Colonists appear to have made some efforts to obtain fish beyond those commonly used by earlier coastal communities. Two of these are freshwater fishes: largemouth basses (Micropterus salmoides) and perches (Perca flavescens). Both are rare in the Santa Elena collection, but even more rare in the baseline assemblage. Perhaps these fish were caught when a spring flood brought freshwater fish into Port Royal Sound, were acquired from people living further inland, or were obtained by colonists venturing inland.

Two fish may represent European or African technologies because they suggest the Spanish fishery might have extended into deeper waters beyond the estuarine waters adjacent to Parris Island. One of these is a snapper, which is associated with warmer waters, such as the deep waters at the outer edge of the continental shelf or warm Caribbean waters. Snappers are the only taxon linking Santa Elena with either of these locations and are not present in the baseline assemblage. The second example is sea bass. Small sea basses are found in estuaries, but only one sea bass specimen (NISP) is present in the baseline assemblage. Sea basses are common in British-American Charleston, however (Reitz and Zierden 2021a, b). They are associated most frequently with Charleston’s nineteenth-century Mosquito Fleet, a fleet of small, open boats operated by African American fishermen who sailed as much as 60 km offshore (Bishop et al. 1994). Perhaps this offshore fishery began at Santa Elena.

It is difficult to say who did most of the fishing, but both Indigenous Americans as well as colonists participated in the fishery. The original supplies brought from Spain to Florida by Menéndez included 200 fishnets (Lyon 1976: 91) and testimony offered in 1570 indicates that settlers did fish, though “with much difficulty and danger on account of the Indians,” which also limited hunting (Connor 1925: 302/303, 312/313). The account of Fray Andrés de San Miguel, shipwrecked near the Altamaha River in 1595, describes soldiers using a canoe to block tidal streams, constructing an impromptu weir, and using cast nets as well as what may have been a small spear or leister (García 1902: 202–203, 208; Hann 2001: 72–73, 79). In St. Augustine, there were commercial fishers (Lyon 1978: 22) and colonists at Santa Elena formed hunting and fishing partnerships (Lyon 1984: 7). Colonists also obtained fish from local Indigenous populations (García 1902: 207; Hann 2001: 78).

Other Aspects of Santa Elena’s Animal Economy

Fish were not the only vertebrate resources used at Santa Elena. Deer are the most abundant wild mammal in the collection (4% of the noncommensal MNI) and raccoons are the most prominent of the small mammals (1% of the MNI). These are also the most common nonfish vertebrates in the baseline assemblage. Rabbits, squirrels, beavers (Castor canadensis), bears, and minks are also present. Venison, however, contributes 32% of the noncommensal biomass. In addition to being sources of meat, wild mammals provided commodities such as hides, pelts, bones, and lubricants valuable locally and as exports. Turkeys are the single most abundant of the wild bird individuals, though 25 of the 47 wild bird individuals are waterfowl and shore birds.

Introduced domestic livestock contribute 13% of the noncommensal MNI and 37% of the noncommensal biomass (Fig. 5; see Table 4). Most of the domestic individuals are chickens (Gallus gallus; 8% of the noncommensal MNI) and pigs (5% of the noncommensal MNI). Chickens contribute 3% of the noncommensal biomass and pigs contribute 33% of the noncommensal biomass. Alonso de Cáceres (1574) reported that chickens in St. Augustine tasted like fish because they ate shellfish (see also Manucy 1985: 39). Cattle are rare. Cattle are usually more abundant than pigs in Georgia Bight collections after 1565, reflecting the free-range cattle industry that flourished in the Georgia Bight into the late 1700s or early 1800s (e.g., Arnade 1961; Dunbar 1961; Hart 2016; Reitz et al. 2010: 83; Stewart 1996; Zierden et al. 2022: Table 11.2). Perhaps the dominance of pigs can be attributed to Miranda’s pig farm. Given the frequent complaints that meat was in short supply, it seems unlikely common soldiers enjoyed this much pork.

Comparison of introduced domestic vertebrates and local, wild vertebrates at Georgia Bight sites discussed in the text; commensal data omitted (see Table 1 for information about each site)

Element representation indicates that pig and deer carcasses were handled in a similar manner. Although both are represented by specimens from the entire skeleton, Foot specimens are underrepresented compared to intact reference skeletons (Fig. 6; Table 6). This suggests differential treatment of lower legs. If parts of the lower legs were left in hides, those bones may have been discarded elsewhere at the site or sold along with the hides, assuming deer hides were among the furs that were part of the town’s external trade (e.g., Lyon 1984: 7). Age at death for pigs and deer shows a preference for young, tender meat; 71% of the pigs (MNI = 29) and 62% (MNI = 23) of the deer died before reaching adulthood. These younger animals likely yielded more tender meat and softer, less blemished hides, both of which are important attributes in commodities.

Comparison of the number of identified pig and deer specimens (NISP) using a logged ratio. “Head” includes skull fragments, antlers, and teeth. “Body” includes vertebrae, ribs, scapula, humerus, radius, ulna, innominate, sacrum, femur, and tibia. “Foot” includes sesamoids, carpals, metacarpals, tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges. Specimens are from Areas 1–8

The Tradition on a Broader Scale

The animal economies at Santa Elena and sixteenth-century St. Augustine were very similar (see Figs. 3 and 5). Fish contributed at least 70% of the noncommensal individuals and 24% of noncommensal biomass at both towns. In St. Augustine, the combination of local wild animals and introduced domestic animals continued into the 1700s, though beef dominated St. Augustine’s animal economy by the eighteenth century, reflecting the importance of the Spanish cattle industry (Arnade 1961; Bushnell 1978; Reitz et al. 2010: 82–83; Reitz and Waselkov 2015).

The combination of estuarine fish, venison, and some use of domestic animals also is found in other Spanish-affiliated coastal collections (e.g., Reitz 1992; Reitz and Cumbaa 1983; Reitz and Scarry 1985). At Mission Santa Catalina de Guale (SCDG), for example, fish contribute 40% of the noncommensal individuals in collections from both the Spanish sector (Eastern Plaza Complex [EPC]) and the Indigenous community associated with the mission (Pueblo Santa Catalina de Guale) (see Fig. 3; Reitz et al. 2010: 120, 155). Deer contribute 72% of the noncommensal biomass in the Eastern Plaza Complex and 83% in the Pueblo. Domestic animals, primarily chickens and pigs, are present in both Santa Catalina de Gaule contexts, though as minor resources. The collection from Mission Nombre de Díos, located just north of St. Augustine, contains no domestic animals though fish contribute 92% of the noncommensal individuals (Reitz 1985, 1991; Reitz et al. 2010: 89). Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, also located just north of St. Augustine, was established in the 1700s for Africans escaping servitude in British colonies (Landers 1990; Reitz 1994). Fish contribute 93% of the noncommensal individuals in the Mose collection, though cattle contributed 50% of the noncommensal biomass.

Spanish-affiliated faunal collections from sites located away from the coast contain higher percentages of domestic animals. San Luis de Talimali was the capital of the Spanish mission chain in western La Florida from 1656 until Colonel Moore destroyed it in 1704 (Reitz 1993). Domestic animals contribute 46% of the noncommensal MNI and 94% of the biomass in the San Luis collection. Most of the individuals are pigs (25% of the noncommensal MNI), but most of the biomass is beef (79%). Other noncoastal mission collections, however, consist largely of local wild animals (Reitz 1993).

Many people at these sites were at least nominally Roman Catholic and the prominence of fish may represent conformity to a religious calendar of meatless days. Undoubtedly this was one motivation, but likely not the only one. Although fish was heavily used, 65% of the noncommensal biomass in the Santa Elena collection is pork and venison. Pork, venison, and beef contribute 59% of the noncommensal biomass in the sixteenth-century St. Augustine collection (Reitz et al. 2010: 82–83). Perhaps more telling, venison contributes 72% of the biomass in the Eastern Plaza Complex collection, the Spanish compound at Mission Santa Catalina de Guale. The choices exercised at these Catholic locations do not appear to emphasize meatless fast days. Regardless of whether the focus on fish was or was not dictated by the religious calendar, the fish in all coastal Spanish collections are estuarine catfishes, drums, and other fishes common in local waters and routinely used by Indigenous Americans throughout the coastal strand for millennia. Cods (Gadidae), salmons (Salmonidae), and herrings (Clupeidae) are notable for their absence even at Santa Catalina de Guale (Reitz et al. 2010: 117–119).

This cultural form persisted in later British and American locations. Fort Frederica was a fortified British settlement established in 1736 by James E. Oglethorpe on St. Simons Island (see Figs. 1, 3 and 5; Table 1; Honerkamp 1982; Honerkamp and Reitz 1980; Reitz and Honerkamp 1983). Most residents left the island when the British regiment was transferred from Frederica in 1745, but Thomas Hird continued living there until his death in 1748. Hird was a dyer, the town constable, and a part-time lay preacher. The Hird collection is noteworthy for its vast array of wild birds. This is an important departure from the baseline assemblage and may be evidence that Hird participated in the feather trade. Wild animals contribute 81% of the Hird individuals, though cattle contribute 67% of biomass.

Similar proportions of wild individuals, primarily fish, to domestic biomass are found in collections from plantations located on the South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida coasts from the 1700s until the 1860s (Reitz 1987). For example, 94% of the noncommensal individuals in Kings Bay Plantation deposits associated with planters are wild as are 81% of the individuals in deposits associated with enslaved plantation workers (Adams et al. 1987: 247, 255). In the collection from Stobo Plantation, located just inland from Charleston, 87% of the noncommensal taxa and 64% of the noncommensal individuals are wild (Webber and Reitz 1999).

This same combination of fish, deer, other wild animals, and beef persisted into the late 1800s in Charleston.; 48% of the noncommensal individuals are wild and beef dominates the biomass (65%; Zierden and Reitz 2016; Zierden et al. 2022: Table 11 − 2). The same first tier fish in Charleston (sea catfishes, sea basses, drums) as well as the second tier (mullets, sheepsheads, flounders) also dominate the Santa Elena collection, with the exception of sea basses (see Reitz and Zierden 2021a).

The New Cultural Form

The animal economy that emerged at Santa Elena is a new cultural form, one that merged Indigenous and Eurasian traditions to form a novel colonial animal economy based largely on estuarine fishing, hunting, and animal husbandry. Similarities between Santa Elena and the baseline assemblage suggest traditional Indigenous knowledge directly and indirectly influenced the colonial animal economy. This new form cannot be attributed entirely to the traditions of either colonists or Indigenous Americans. It brought together both traditions and is an important reminder that traditional Indigenous knowledge could be an important influence in colonial animal economies.

It is difficult to isolate attributes in the Santa Elena example that might be traced to persistence, adaptation, or appropriation. It seems unlikely this was an adaptation by colonists to local conditions which developed independent of a local example to follow: there was a local example to follow and skilled Indigenous practitioners who were actively engaged with colonists. Indigenous Americans also provided goods and services to the town as trade, tribute, and tithes. To the extent that Santa Elena households included Indigenous women, their local knowledge and their kinship networks offered additional avenues through which ingredients in the baseline assemblage entered the town. Colonists also fished and hunted for themselves, apparently using many of the same strategies long practiced in the area, combining this with their own tradition of animal husbandry.

Thus, Santa Elena’s animal economy was the product of dynamic interactions and exchanges among colonists and Indigenous communities. These multiple actors merged traditional Indigenous knowledge with colonists’ traditions of animal husbandry to produce a new cultural form. Although it might be possible to argue that colonists in La Florida were eating anything they could get their hands on because of food shortages, what they were eating were foods enjoyed by people along the Georgia Bight for millennia. Many of these foods continue to be enjoyed today. The widespread adoption and subsequent persistence of this new cultural form suggests reliance on wild resources by colonists was not simply because Indigenous Americans willingly or unwillingly supported colonists through trade or coercion. Nor was the sixteenth-century animal economy at Santa Elena, as well as at St. Augustine, a short-lived expedient practiced to compensate for an irregular supply line and food insecurity and subsequently abandoned.

Although similar to local practices before 1565 in many respects, this new cultural form did not rely entirely on Indigenous suppliers or examples. Indigenous Americans undoubtedly did supply wild resources as well as traditional knowledge to colonists into the eighteenth century, if not later, but it seems likely European and African immigrants observed fishing, trapping, and hunting methods practiced by local fishing communities, expanded upon those skills, and used them as their own. This is particularly the case for fisheries. New technologies, such as cotton-fiber cast nets, lead weights, metal hooks, and sailboats, made it possible to go into the deeper waters of the continental shelf in pursuit of species, such as blackfishes, which are more abundant offshore.

Different choices were made elsewhere, even in La Florida, often with more emphasis on animal husbandry (e.g., Deagan and Reitz 1995; Reitz and McEwan 1995), but the coastal tradition that began at Santa Elena, as well as St. Augustine, persisted throughout the Georgia Bight into the nineteenth century. A version of this cuisine continues into the present century, appearing on the menus of expensive urban restaurants, rural diners, political rallies, club socials, and family gatherings. The persistence of this new form into later centuries suggests the combination of an estuarine fishery and animal husbandry was a success.

Conclusions

The influence of a traditional fishery on colonial animal economies in the Georgia Bight suggests that we should not view colonial settings as ones in which all influences flowed from “colonist” to “colonized.” At least in the context of Santa Elena’s animal economy, it cannot be said the dominant influence was exclusively Spanish. There was a very strong Indigenous influence. With the exception of domestic stock, the approach to provisioning Santa Elena was very similar to that practiced for millennia by Indigenous Americans in the same area. Perhaps the vertebrate data from Santa Elena are evidence of food insecurity among the colonists, as colonists claimed. Alternatively, these data could be evidence that Indigenous Americans were coerced into supplying food to the colonists. Nonetheless, Indigenous techniques and choices become integral to later coastal animal economies. The new cultural form that emerged at Santa Elena and St. Augustine in the sixteenth century was incorporated into Spanish, British, and American animal economies throughout the Georgia Bight. The persistence of this new cultural form throughout the southeastern Atlantic coast suggests these practices, once established, were long-lived and fundamental to everyday life on a bountiful coast. Studies of other colonial settings, especially coastal ones regardless of time or place, should consider the influence of local traditional knowledge on colonial economies, the possibility that the traditions and practices of colonizers changed very quickly, and that the new cultural forms persisted long after the colonial period ended.

References

Adams, W. H., Rock, C., and Kearney-Williams, J. (1987). Foodways on the plantations at Kings Bay: hunting, fishing, and raising food. In Adams, W. H. (ed.), Historical Archaeology of Plantations at Kings Bay, Camden County, Georgia. Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 225–276.

Arnade, C. W. (1959). Florida on Trial. University of Miami Press, Coral Gables, FL.

Arnade, C. W. (1961). Cattle raising in Spanish Florida. Agricultural History 35(3):3–11.

Beaule, C. D. (ed.) (2017). Frontiers of Colonialism. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Beck, R. A., Newsom, L. A., Rodning, C. B., and Moore, D. G. (2017). Spaces of entanglement: labor and construction practices at Fort San Juan de Joara. Historical Archaeology51:167–193.

Becker, S. K. (2013). Health consequences of contact on two seventeenth-century native groups from the Mid-Atlantic region of Maryland. International Journal of Historical Archaeology17:713–730.

Bennett, C. E. (trans. and ed.) (1975). Three Voyages: René Laudonnière. University Presses of Florida, Gainesville.

Bergh, S. G. (2012). Subsistence, Settlement, and Land-use Changes during the Mississippian Period on St. Catherines Island, Georgia. Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens.

Bishop, J. M., Ulrich, G., and Wilson, H. S. (1994). “We are in trim to due it”: a review of Charleston’s Mosquito Fleet. Journal of Fisheries Science2(4):331–346.

Bolton, H. and Ross, M. (1968). The Debatable Land. Russell and Russell, New York.

Braund, K. E. H. (1993). Deerskins and Duffels: Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Bushnell, A. (1978). The Menéndez Marquéz cattle barony at La Chua and the determinants of economic expansion in seventeenth-century Florida. Florida Historical Quarterly56(4):407–431.

Bushnell, A. (1981). The King’s Coffer. University Presses of Florida, Gainesville.

Campana, D. V., Crabtree, P., deFrance, S. D., Lev-Tov, J., and Choyke, A.M. (eds.) (2010). Anthropological Approaches to Zooarchaeology: Complexity, Colonialism, and Animal Transformations. Oxbow, Oxford.

Clute, J. R. and Waselkov, G. A. (2002). Faunal remains from Old Mobile. Historical Archaeology36(1):129–134.

Connor, J. T. (trans. and ed.) (1925). Colonial Records of Spanish Florida: Letters and Reports of Governors and Secular Persons. Vol. 1:1570–1577. Florida State Historical Society, Deland.

Connor, J. T. (trans. and ed.) (1930). Colonial Records of Spanish Florida: Letters and Reports of Governors, Deliberations of the Council of the Indies, Royal Decrees, and other Documents. Vol. 2:1577–1580. Florida State Historical Society, Deland.

Crabtree, P. J. and Ryan, K. (eds.) (1991). Animal Use and Culture Change. University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Cusick, J. G. (ed.) (1998). Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Dahlberg, M. E. (1975). Guide to Coastal Fishes of Georgia and Nearby Waters. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

Cáceres, Alonso de (1574). Dec 12, 1574, AGI, 54-2-2, Santo Domingo 124. J. T. Connor Papers, Reel 2. P. K. Yonge Library, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Deagan, K. A. (1973). Mestizaje in colonial St. Augustine. Ethnohistory20(1):55–65.

Deagan K. A. (1980). Spanish St. Augustine: America’s first “melting pot.” Archaeology33(5):22–30.

Deagan, K. A. (ed.) (1983). Spanish St. Augustine: The Archaeology of Colonial Creole Community. Academic Press, New York.

Deagan, K. A. (1990). Sixteenth century Spanish colonization in the Southeastern United States and the Caribbean. In Thomas, D. H. (ed.), Columbian Consequences,Vol. 2. Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East. Smithsonian Press, Washington, DC, pp. 225–250.

Deagan, K. A. (1998). Transculturation and Spanish American ethnogenesis: the archaeological legacy of the quincentenary. In Cusick, J. G. (ed.), Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, pp. 23–43.

Deagan, K. A. (2003). Colonial origins and colonial transformations in Spanish America. Historical Archaeology 37(4):3–13.

Deagan, K. A. (2004). Reconsidering Taíno social dynamics after Spanish conquest: gender and class in culture contact studies. American Antiquity69(4):597–626.

Deagan, K. A. and Reitz, E. J. (1995). Merchants and cattlemen: the archaeology of a commercial structure at Puerto Real. In Deagan, K. (ed.), Puerto Real: The Archaeology of a Sixteenth-Century Spanish Town in Hispaniola. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 231–284.

deFrance, S. D. (1999). Zooarchaeological evidence of colonial culture change: a comparison of two locations of Mission Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga and Mission Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Texas. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society70:169–189.

deFrance, S. D. (2003). Diet and provisioning in the high Andes: a Spanish colonial settlement on the outskirts of Potosí, Bolivia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology7:99–126.

deFrance, S. D. and Hanson, C. A. (2008). Labor, population movement, and food in sixteenth-century Ek Balam, Yucatán. Latin American Antiquity19:299–316.

deFrance, S. D., Wernke, S. A., and Sharpe, A. E. (2016). Conversion and persistence: analysis of faunal remains from an early Spanish colonial doctrinal settlement in highland Peru. Latin American Antiquity27(3):300–317.

DePratter, C. B. (2009). Irene and Altamaha ceramics from the Charlesfort/Santa Elena site, Parris Island, South Carolina. In Deagan, K. and Thomas, D. H. (eds.), From Santa Elena to St. Augustine: Indigenous Ceramic Variability (AD 1400–1700). American Museum of Natural History, New York, pp. 19–48.

DePratter, C. B. and South, S. (1995). Discovery at Santa Elena: Boundary Survey. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Dietler, M. (2010). Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Dunbar, G. S. (1961). Colonial Carolina cowpens. Agricultural History35(3):125–130.

Dunkle, J. R. (1958). Population change as an element in the historical geography of Florida. Florida Historical Quarterly37:3–32.

Ewen, C. R. (2009). The archaeology of La Florida. In Majewski, T. and Gaimster, D. (eds.), International Handbook of Historical Archaeology. Springer, New York, pp. 383–398.

Froese, R. and Pauly, D. (eds.) (1998). FishBase98: Concepts, Designs and Data Sources. The International Center for Living Resources Management, Kakati City, Philippines. Electronic document, FishBase98. www.fishbase.org; accessed March 3, 2022.

García, G. (ed.) (1902). Dos Antiguas Relaciones de la Florida. J. Aguilar Vera y Comp., Mexico City.

Gifford-Gonzalez, D. and Sunseri, K. U. (2007). Foodways on the frontier: animal use and identity in early colonial New Mexico. In Twiss, K. C. (ed.), The Archaeology of Food and Identity. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, pp. 260–287.

Gonzalez, S. L. and Panich, L. M. (2021). Situating archaeological approaches to indigenous-colonial interactions in the Americas: an introduction. In Panich, L. M. and Gonzalez, S. L. (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of the Archaeology of Indigenous-Colonial Interaction in the Americas. Routledge, London, pp. 3–13.

Gremillion, K. J. (2002a). Archaeobotany at Old Mobile. In Waselkov, G. A. (ed.), French Colonial Archaeology at Old Mobile: Selected Studies. Historical Archaeology36(1):117–128.

Gremillion, K. J. (2002b). Human ecology at the edge of history. In Wesson, C. B. and Rees, M. A. (eds.), Between Contacts and Colonies. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, pp. 12–31.

Grimstead, D. N. and Pavao-Zuckerman, B. (2016). Historical continuity in Sonoran Desert free-range ranching practices: carbon, oxygen, and strontium isotope evidence from two 18th-century missions. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports7:37–47.

Hakluyt, R. (1966). Divers Voyages Touching on the Discoverie of America. Readex Microprint Corporation, Thomas Woodcocke, London.

Hann, J. H. (trans.) (2001). An Early Florida Adventure Story, by Fray Andrés de San Miguel. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Hardy, M. D. (2011). Living on the edge: foodways and early expressions of Creole culture on the French colonial Gulf Coast frontier. In Kelly, K. G. and Hardy, M. D. (eds.), French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 152–188.

Hart, E. (2016). From field to plate: the colonial livestock trade and the development of an American economic culture. William and Mary Quarterly73(1):107–140.

Hoffman, P. E. (1990). A New Andalucia and a Way to the Orient: The American Southeast during the Sixteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge.

Honerkamp, N. (1982). Social status as reflected by faunal remains from an eighteenth century British colonial site. Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers 1979 14:87–115.

Honerkamp, N. and Reitz, E. J. (1980). Eighteenth century British colonial adaptations on the coast of Georgia: the faunal evidence. In Ward, A. E. (ed.), Forgotten Places and Things: Archaeological Perspectives on American History. Albuquerque, New Mexico, pp. 335–339.

Jones, E. L. (2016). Changing landscapes of early colonial New Mexico. In Herhahn, C. L. and Ramenofsky, A. F. (eds.), Exploring Cause and Explanation: Historical Ecology, Demography, and Movement in the American Southwest. University of Colorado Press, Boulder, pp. 73–90.

Jordan, K. A. (2009). Colonies, colonialism, and cultural entanglement: the archaeology of Postcolumbian intercultural relations. In Majewski, T. and Gaimster, D. (eds.), International Handbook of Historical Archaeology. Springer, New York, pp. 31–49.

Joseph, J. W. and Zierden, M. A. (2002). Cultural diversity in the southern colonies. In Joseph, J. W. and Zierden, M. (eds.), Another’s Country: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Cultural Interactions in the Southern Colonies. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, pp. 1–12.

Kelly, K. G. and Hardy, M. D. (eds.) (2011). French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Landers, J. (1990). Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose: a free black town in Spanish colonial Florida. American Historical Review95(1):9–30.

Lapham, H. (2005). Hunting for Hides: Deerskins, Status, and Cultural Change in the Protohistoric Appalachians. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Larsen, C. S., Griffin, M. C., Hutchinson, D. L., Noble, V. E., Norr, L., Pastor, R. F., Ruff, C. B., Russell, K. F., Schoeninger, M. J., Schultz, M., Simpson, S. W., and Teaford, M. F. (2001). Frontiers of contact: bioarchaeology of Spanish Florida. Journal of World Prehistory15(1):69–123.

Lightfoot, K. G., Panich, L. M., Schneider, T. D., Gonzalez, S. L., Russell, M. A., Modzelewski, D., Molino, T., and Blair, E. H. (2013). The study of indigenous political economies and colonialism in native California: implications for contemporary tribal groups and federal recognition. American Antiquity78:89–104.

Lyon, E. (1976). The Enterprise of Florida. University Presses of Florida, Gainesville.

Lyon, E. (1978). St. Augustine 1580: the living community. El Escribano14:20–33.

Lyon, E. (1981). Spain’s sixteenth-century North American settlement attempts: a neglected aspect. Florida Historical Quarterly3:275–291.

Lyon, E. (1984). Santa Elena: A Brief History of the Colony, 1566–1587. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Lyon, E. (1992). Richer than we thought: the material culture of sixteenth-century St. Augustine. El Escribano29:1–117.

Lyons, C. L. and Papadopoulos, J. K. (eds.) (2002). The Archaeology of Colonialism. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California.

Manucy, A. (1985). The physical setting of sixteenth-century St. Augustine. Florida Anthropologist38(1–2):34–53.

Marcoux, J. B. (2010). Pox, Empire, Shackles, and Hides: The Townsend Site, 1670–1715. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Mondini, M., Muñoz, S., and Wickler, S. (eds.) (2004). Colonisation, Migration and Marginal Areas: A Zooarchaeological Approach. Oxbow, Oxford.

Mrozowski, S. A., Franklin, M., and Hunt, L. (2008). Archaeobotanical analysis and interpretations of enslaved Virginian plant use at Rich Neck Plantation (44WB52). American Antiquity73:699–728.

Noe, S. J. (2022). Zooarchaeology of Mission Santa Clara de Asìs: bone fragmentation, stew production, and commensality. International Journal of Historical Archaeology26:908–950.

Orr, K. L. and Lucas, G. S. (2007). Rural-urban connections in the southern colonial market economy: zooarchaeological evidence from the Grange Plantation (9CH137) trading post and cowpens. South Carolina Antiquities39(1 and 2):1–17.

Paar, K. L. (1999). “To Settle is to Conquer”: Spaniards, Native Americans, and the Colonization of Santa Elena in the Sixteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Panich, L. M., DeAntoni, G., and Schneider, T. D. (2021). “By the aid of his Indians”: native negotiations of settler colonialism in Marin County, California, 1840–70. International Journal of Historical Archaeology25:92–115.

Pauly, D. and Christensen, V. (1995). Primary production required to sustain global fisheries. Nature374:255–257.

Pavao-Zuckerman, B. (2000). Vertebrate subsistence in the Mississippian-Historic transition. Southeastern Archaeology19:135–144.

Pavao-Zuckerman, B. (2007). Deerskins and domesticates: Creek subsistence and economic strategies in the Historic Period. American Antiquity72:5–34.

Pavao-Zuckerman, B. and LaMotta, V. M. (2007). Missionization and economic change in the Pimería Alta: the zooarchaeology of San Agustín de Tucson. International Journal of Historical Archaeology11:241–268.

Pavao-Zuckerman, B. and Loren, D. D. (2012). Presentation is everything: foodways, tablewares, and colonial identity at Presidio Los Adaes. International Journal of Historical Archaeology16:199–226.

Pavao-Zuckerman, B. and Reitz, E. J. (2011). Eurasian domestic livestock in Native American economies. In Smith, B. D. (ed.), The Subsistence Economies of Indigenous North American Societies. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Washington, DC, pp. 577–591.

Peres, T. M. (2022). Subsistence and food production economies in seventeenth–century Spanish Florida. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-022-00667-2.

Perttula, T. (2010). Perspectives on Native American-European culture contact. In Perttula, T. (ed.), Perspectives from Historical Archaeology, Vol. 3. Society for Historical Archaeology, Germantown, MD, pp. 1–14.

Quitmyer, I. R. and Reitz, E. J. (2006). Marine trophic levels targeted between A.D. 300 and 1500 on the Georgia coast, USA. Journal of Archaeological Science33:806–822.

Reitz, E. J. (1982). Vertebrate remains from Santa Elena: 1981 excavations. In South, S., Exploring Santa Elena 1981. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, pp. 143–164.

Reitz, E. J. (1983). Vertebrate remains from Santa Elena, 1982 excavations. In South, S., Revealing Santa Elena. Research Manuscript Series No. 188. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, pp. 91–112.

Reitz, E. J. (1985). A comparison of Spanish and aboriginal subsistence on the Atlantic coastal plain. Southeastern Archaeology4(1):41–50.

Reitz, E. J. (1987). Vertebrate fauna and socio-economic status. In Spencer–Wood, S. (ed.), Consumer Choice in Historical Archaeology. Plenum, New York, pp. 101–119.

Reitz, E. J. (1991). Animal use and culture change in Spanish Florida. In Crabtree, P. J. and Ryan, K. (eds.), Animal Use and Culture Change. University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, pp. 62–77.

Reitz, E. J. (1992). Vertebrate fauna from seventeenth century St. Augustine. Southeastern Archaeology11(2):79–94.

Reitz, E. J. (1993). Evidence for animal use at the missions of Spanish Florida. In McEwan, B. G. (ed.), The Spanish Missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 376–398.

Reitz, E. J. (1994). Zooarchaeological analysis of a free African community: Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose. Historical Archaeology28(1):23–40.

Reitz, E. J. (2004). Fishing down the food web: a case study from St. Augustine, Florida, U.S.A. American Antiquity69:63–83.

Reitz, E. J. (2017). Vertebrate remains from a sixteenth-century Spanish capital: Santa Elena (38BU162), USA. Ms. on file, Zooarchaeology Laboratory, University of Georgia.

Reitz, E. J. (2021). A case study in the longevity of a regional estuarine fishing tradition: the central Georgia Bight (USA). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences13(86). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01347-8.

Reitz, E. J. and Cumbaa, S. L. (1983). Diet and foodways of eighteenth century Spanish St. Augustine. In Deagan, K. A. (ed.), Spanish St. Augustine: The Archaeology of a Colonial Creole Community. Academic Press, New York, pp. 147–181.

Reitz, E. J. and Honerkamp, N. (1983). British colonial subsistence strategy on the southeastern coastal plain. Historical Archaeology17(2):4–26.

Reitz, E. J. and McEwan, B. G. (1995). Animals, environment, and the Spanish diet at Puerto Real. In Deagan, K. (ed.), Puerto Real: The Archaeology of a Sixteenth-Century Spanish Town in Hispaniola. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 287–334.

Reitz, E. J. and Quitmyer, I. R. (1988). Faunal remains from two coastal Georgia Swift Creek sites. Southeastern Archaeology7:95–108.

Reitz, E. J. and Scarry, C. M. (1985). Reconstructing Historic Subsistence with an Example from Sixteenth Century Spanish Florida. The Society for Historical Archaeology Special Publication No. 3, Germantown, MD.

Reitz, E. J. and Waselkov, G. A. (2015). Vertebrate use at early colonies on the southeastern coasts of eastern North America. International Journal of Historical Archaeology19:21–45.

Reitz, E. J. and Wing, E. S. (2008). Zooarchaeology. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Reitz, E. J. and Zierden, M. A. (2021a). A zooarchaeological study of households and fishing in Charleston, South Carolina, USA, 1710–1900. International Journal of Historical Archaeology25:1087–1112.

Reitz, E. J. and Zierden, M. A. (2021b). From Charleston to St. Augustine: changes in the central Georgia Bight (USA) fishery, CE 1565–1900. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports35(21). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102791.

Reitz, E. J., Gibbs, T., and Rathbun, T. A. (1985). Archaeological evidence for subsistence on coastal plantations. In Singleton, T. A. (ed.), The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life. Academic Press, New York, pp. 163–191.

Reitz, E. J., Quitmyer, I. R., and Marrinan, R. A. (2009). What are we measuring in the zooarchaeological record of Prehispanic fishing strategies in the Georgia Bight, USA? Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology4(1):2–36.

Reitz, E. J., Pavao-Zuckerman, B., Weinand, D. C., and Duncan, G. A. (2010). Mission and Pueblo of Santa Catalina de Guale, St. Catherines Island, Georgia. American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Reitz, E. J., Saul, B. M., Moak, J. W., Carroll, G. D., and Lambert, C. W. (2012). Interpreting seasonality from modern and archaeological fishes on the Georgia coast. In Reitz, E. J., Quitmyer, I. R., and Thomas, D. H. (eds. and conts.), Seasonality and Human Mobility along the Georgia Bight. American Museum of Natural History, New York, pp. 51–81.

Reitz, E. J., Colaninno, C. E., Quitmyer, I. R., and Cannarozzi, N. R. (2022). A 4,000-year record of multifaceted fisheries in the central Georgia Bight (USA). Southeastern Archaeology41(4):253–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/0734578X.2022.2134084.

Rodríguez-Alegría, E. (2005). Eating like an Indian: negotiating social relations in the Spanish colonies. Current Anthropology46(4):551–573.

Scott, E. M. (2007). Pigeon soup and plover in pyramids: French foodways in New France and the Illinois Country. In Twiss, K. C. (ed.), The Archaeology of Food and Identification. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, pp. 243–239.

Scott, E. M. and Dawdy, S. L. (2011). Colonial and creole diets in eighteenth-century New Orleans. In Kelly, K. G. and Hardy, M. D. (eds.), French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 97–116.

Senatore, M. X. (2022). Bridging conceptual divides between colonial and modern worlds: insular narratives and the archaeologies of modern Spanish colonialism. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-022-00668-1.

Shannon, C. E. and Weaver, W. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

Sheldon, A. L. (1969). Equitability indices: dependence on the species count. Ecology50:466–467.

Silliman, S. J. (2001). Theoretical perspectives on labor and colonialism: reconsidering the California missions. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology20(4):379–407.

Silliman, S. W. (2020). Colonialism in historical archaeology: a review of issues and perspectives. In Orser, C. E., Zarankin, A., Funari, P. P. A., Lawrence, S., and Symonds, J. (eds.), Colonialism in Historical Archaeology. Routledge, London, pp. 41–69.

Silvia, D. E. (2002). Native American and French cultural dynamics on the Gulf coast. Historical Archaeology36(1):26–35.