Abstract

This paper is the first comprehensive and interdisciplinary presentation of stone walls in the Central European mountains from the perspective of landscape archaeology based on field surveys and analysis of cartographic and LiDAR data. The stone walls in the Izera Mountains of southwestern Poland are the largest ones in the region, as they represent a rare case of fully enclosed fields in the Sudetes. The niches constructed within the walls are not found anywhere else. The paper discusses the origins, functions, chronology, construction techniques, spatial distribution, and diversity of stone walls and also their significance for the cultural landscape, which was subject to substantial land abandonment after World War 2. Stone walls marked field boundaries, protected arable lands from erosion and their niches provided storage places, and provisional dwellings. Nowadays they are spectacular remnants of past land-use and unique features of the regional cultural landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adapting upland and mountainous areas to the needs of agriculture usually requires special techniques and much work (Klápšte and Sommer 2009). As a result, in some regions of the world stone walls and heaps that permanently change both the cultural landscape and an ecosystem were erected. The character and significance of this phenomenon until now have been studied mainly in northern Europe and in the British Isles, where stone field boundaries are an important element of cultural heritage (Collier 2013; Defining Stone 2007; McAfee 1997; Marshall and Moonen 2002). Thorough research was also conducted in North America, where European colonists used techniques known from the Old Continent (Allport 1994; Johnson and Ouimet 2016, 2018; Thorson 2004, 2005). Close to the southern Polish border, studies that focused on the significance of such walls for the ecosystem, similar to the studies from other European countries (Manenti 2014; Schreg 2016), were conducted in the Czech Republic (Duchoslav 2002; Hartmanová 2005). Stone walls and heaps that occur in the mountainous areas in Central and Eastern Europe are not as frequent and densely distributed as those from the British Isles, and they only sporadically form closed fences around old fields. Other materials were sometimes also used to supplement stone, like wooden fences. Nevertheless, they are an important element of the cultural landscape of the region, which lets us define the area occupied by agricultural activity in the past. It is even more significant in relation to profound changes in land use that were introduced in the region after World War 2 – stone structures are often the only evidence of traces of past agriculture that can be seen in the landscape. The state of research on this issue is not as advanced as in Britain or the USA, and the literature is quite limited. The first recently released publications were focused on structures that can be found in the Carpathians (Affek 2016b; Wolski 2007) as well as the Sudetes on the Polish (Latocha 2009, 2014; Migoń 2012a, 2012b) and Czech sides (Spurný 2006). Such constructions usually have the form of stone heaps (prisms) and walls, not closed fences. Moreover, in most of the previous publications, scholars have concentrated on morphometric characteristics of the structures. However, the aim of this paper is to give the first comprehensive presentation of stone walls, including not only their form and morphometry, but also to determine their origins, functions, chronology, construction techniques, and their significance for the cultural landscape of the Izera Mountains in the southwest of present-day Poland. The choice of the area was determined by the occurrence of unique structures that significantly differ from those that are known from other parts of the Sudetes. Their uniqueness consists in that these are the largest stone walls in the Sudetes, and also because the niches are not found anywhere else. Stone walls in the Izera–Karkonosze region are also the only example in the Sudetes and a rare case of fully enclosed fields in the Central European mountains, as in other areas walls were located either parallel or perpendicular to a slope. Despite the uniqueness of these forms in the Sudetes region, they have been only briefly discussed, and solely in popular science literature (Łuczyński et al. 2015; Migoń 2012a, 2012b).

Study Area: Environmental and Historical Background

Location and Environment

The researched area encompasses the southern and northern slopes of the Kamieniecki Ridge in the Izera Mountains (Lower Silesia, Poland), located above the villages of Kopaniec, Chromiec, Antoniów, and Górzyniec, where the highest-density of the most spectacular examples of field boundaries in the whole Izera-Karkonosze region were recorded. A large number of other stone structures (prisms, single walls) connected with historical agriculture can also be found there. The area covers 30 km2 altogether (Fig.1) and is located 12 km north of the border with the Czech Republic.

The Kamieniecki Ridge is one of the main ridges in the Izera Mountains on the Polish side. It runs latitudinally and its highest hill is Kamienica (973 m above sea level). In terms of physiographic aspects it belongs to the Western Sudetes (Kondracki 2002). The characteristic features of the relief are the vast flattened hill tops with slightly elevated culminations. In the south, the slopes of the Kamieniecki Ridge drop steeply to a deep latitudinally situated valley of the Kamienna Mała stream. More gentle northern slopes of the Kamieniecki Ridge are cut by numerous shallow longitudinal valleys of spring streams of the Kamienica River and its tributaries. Most villages of the Waldhufendorf type (forest village) were founded along these valleys.

From a geological perspective the Kamieniecki Ridge belongs to the Izera Mountains metamorphic structures which are part of the Izera-Karkonosze fault block. It is mostly built of several different types of Palaeozoic gneisses and also granite-gneisses, leucogranites, granitoides, and mica schists (Detailed Geological Map of Sudetes 1:25,000 2004). They form extensive weathering mantles with numerous rock debris in the topmost layer of slope covers, which became the source material for construction of stone walls and heaps. The debris covers date back mainly to the Pleistocene period, when the region was subject to periglacial conditions with intense frost weathering of rock outcrops (Migoń 2005).

In metamorphic rocks of the Izera Mountains various precious and semi-precious stones can be found. Their occurrence became a reason for the development of mining and exploration works conducted in the region starting in the Middle Ages. In the area of the Kamieniecki Ridge the following resources were exploited on a larger scale: tin and cobalt ores (fifteenth–twentieth century) and quartz (until the twenty-first century) as well as rocks: gneisses, leucogranites, and mica schists. Traces of historical mining still can be noticed in the landscape in the form of numerous stone heaps, pits, and adits (Madziarz and Sztuk 2006).

The Izera Mountains are characterised by a cool climate (the annual average temperature at an altitude of 450–600 m a.s.l. equals 6.5 °C) and high rainfall levels (1200–1500 mm annually in the upper parts of the mountains). The vegetation period lasts 175–200 days and there is no thermal summer in the higher parts of the slopes. Another characteristic feature is frequent strong winds, usually south westerly (Staffa 1989). Harsh climate conditions are determined mainly because the Izera Mountains form an orographic barrier for the maritime air masses from the Atlantic Ocean. What is more, the main landform pattern contributes to the forming of drains and accumulation of cold air. In the area of the Izera Mountains there is a place regarded as the Polish “pole of cold”(Hala Izerska).

Soils on the slopes of the Izera Mountains are shallow and contain a large amount of the rock base, which is why they are not fertile and require much work and agrotechnical measures. According to a classification of agricultural usefulness they belong to a group of mountain complexes growing cereals, potatoes, and oat-fodder (Soil agricultural map at a scale of 1:25,000 2004).

The History of Settlement and Economic Activity

The analyzed area was settled relatively late. There is no evidence of prehistoric settlements in the study area. In the low-located zone, at an altitude of around 200–350 m a.s.l., rare early medieval (tenth–twelfth century) settlements were established, but it was mainly in the thirteenth–fourteenth century that the settlement network dynamically developed. New villages, towns, and fortified residences were erected as a result of a planned colonization organized by Silesian rulers from the Piast Dynasty (Chorowska et al. 2017). Settlers from the German lands were a demographic base for the campaign. Colonization in the discussed area dates back to the late thirteenth century, but it reached its highest intensity mainly in the fourteenth century (Adamska 2016). At that time, the largest town of the region – Jelenia Góra – and its neighbouring villages were founded. New local administration units (districtus) along with a parish network were established. In the vicinity of the study area the village of Kamienica/Kemnitz appeared. There is no record of agricultural activity in the Izera Mountains, in the area of the Kamieniecki Ridge, for the earliest period of settlement development. Written sources and archaeological records indicate that the economic base for local communes was varied. Glassworks, metal ore mining connected with silviculture, and marginal agriculture are mentioned. The oldest village in the discussed area is Kopaniec (Seifershau), founded in 1337. Henry Duke of Jawor, handed 54 Hufen (an old unit of field measurement, 1 Hufe = ca. 24 ha) of forest for cutting down and settling to Peter von Borau. In 1399 the existence of the Church of St. Anthony was confirmed (Regesty Śląskie 1975; Adamska 2016). The origins of neighbouring villages are probably connected with the modern period (seventeenth–eighteenth century).

For the analysis of stone walls the most important are the changes in the village of Kopaniec. The varied layout of the village is confirmation of its complex spatial development in various periods. Within the village two main parts are clearly visible. The first part, situated at lower altitudes, significantly differs in terms of morphology from the younger part that developed at a higher elevation. The differences are particularly visible on old medium-scale maps (Urmeßtischblätter and Meßtischblätter) (Fig. 2), where a gap between the two parts of the village can be noticed. The village’s layout varies from longitudinal (the lower/main part of the village) to latitudinal (the upper part of the village). The lower part is a forest village (Waldhufendorf), with fields situated behind dwellings (Biermann 2010:336–344). Development after the seventeenth century, (and the expansion to new areas) probably resulted because the village was not destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), unlike many other villages in Lower Silesia. The population was increasing (1023 inhabitants in 1782, 1170 in 1840; Staffa 1989) and settlers entered the higher-located zone, previously regarded as useless for settlement purposes. The process resulted in a considerable difference in altitude between the lower and the upper part of the village, which equalled nearly 400 m (from around 440 to 740 m a.s.l.). The upper part of Kopaniec was founded at a different time and in different natural conditions than the lower part and has not acquired the layout of a Waldhufendorf, with buildings situated along the street. The layout is irregular and conditioned by the local topography. Such settlements, called “self-developing” (spontaneous), did not come into existence as a result of a planned campaign, but developed over time (Szymańska 2013). Therefore, homesteads in the area of upper Kopaniec are scattered. The process caused the need to occupy for agricultural purposes areas situated south of the upper village, at altitudes up to 800 m a.s.l. Similar conditions for agriculture were experienced by those who inhabited the neighboring villages of Antoniów/Antonienwalde and Chromiec/Ludwigsdorf. Antioniów was founded in the mid-seventeenth century. It is a dispersed settlement, situated at an altitude of 520–550 m a.s.l.. During its peak development (in 1840), over 300 inhabitants lived in the village. Chromiec is also a dispersed village located 490–580 m a.s.l. It was probably founded in the late fourteenth century in connection with establishing a forest glassworks in this area. It reached the largest number of inhabitants (660) in the late eighteenth century, but has been decreasing ever since.

The phenomenon of abandoning hard-to-acquire, high-located fields started in the second half of the nineteenth century due to the development of industry in the nearby towns, which triggered migration from the mountain areas. It was a typical process in many regions of the Sudetes (Latocha 2013:373–374; Walczak 1968). This tendency intensified after the changes of state borders after World War 2 and subsequent population exchanges. The Germans were replaced with Poles. Many homesteads in the researched area did not become inhabited again and others were being continuously abandoned in the following decades due to the withdrawal of agriculture from high elevated areas. It was the result of both improvements in cultivation techniques in lower areas and the lack of the possibility to use mechanical equipment in difficult environmental conditions in the mountains. Only a small part of former arable lands is still in use today, usually as pasture. No contemporary cultivation was recorded on any of the plots located in the upper parts of the village. A secondary succession of plants on some of former arable lands to some extent today blur the field and plot divisions. However, in the area where stone walls occur, there are different plant species growing than in other places, which helps to identify the walls and field boundaries regardless of vegetation. It is particularly visible in forested areas – stone walls and prisms are covered mainly with deciduous trees, whereas coniferous forest dominates the neighborhood.

Materials and Methods

The analyses were conducted based on contemporary topographic maps at a scale of 1:10000, data acquired through Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) at a resolution of 0.5 m and detailed field studies, including field surveys and morphometric analysis. Archaeological excavations were also conducted at a chosen, representative stone structure in order to define its chronology and function. The old topographic (ca. 1764–70 and 1824–26) and cadastral maps (ca. 1870–1930) were additional valuable sources of information.

LiDAR data are widely used for detecting, reconstructing, and reinterpretating cultural landscapes, and numerous papers deal either with site-specific case studies throughout the world (i.e., Bernardini et al. 2013; Bewley et al. 2005; Chase et al. 2011; McNeary 2014), or with a methodological aspect, especially addressing technical problems and solutions, various interpretation methods, and constraints (i.e., Bennett et al. 2012; Challis et al. 2011) (see more on literature overview in Johnson and Ouimet 2018). However, in mountain areas in Poland the studies on interpretation of past cultural landscapes using LiDAR data are scarce. The most thorough research was conducted in the southeast Carpathians (Affek 2016a, 2016b) and at selected sites in the Sudetes (Migoń and Latocha 2018). LiDAR became a very efficient tool for studies on past cultural landscapes, though the interpretation of data should be treated with caution due to numerous limitations of this method. Therefore, its interpretative value should be supplemented with other data sources, such as aerial and ground photographs or cartographic materials from various time periods, as many authors have stressed. Obviously, these additional sources have their own limitations, exemplified by the use of old cadastral and topographic maps (i.e., Forejt et al. 2018; Kaim et al. 2014) or other non-invasive techniques (i.e., Ivanišević et al. 2015; Opitz and Cowley 2013). Therefore, only the combination of various methods can be a proper research approach to achieve the most comprehensive reconstruction and interpretation of past cultural landscapes. In our study we focused especially on field surveys, including inventory and morphometry of the walls, as well as preliminary archaeological excavations. Both cartographic and LiDAR data were used as supplementary information on the locations and spatial contexts of stone walls.

The basic problem that we experienced during the fieldwork was defining the precise chronology of the described constructions. The construction process was probably gradual over time. The heavy weight and considerable size of some rocks must have caused logistical problems connected with transportation and the proper location along a field border. That is why the blocks were commonly crushed into smaller fragments. Such work was surely time-consuming.

LiDAR Data and Processing

LiDAR data was obtained from measurements made for the whole of Poland. These measurements are available in the form of sheets whose dimensions depend on the scale. There are two types of scale available for LiDAR data: 1:1250 (for urban areas) and 1:2500 (for any other areas). The studied area covers an area of approximately 59.18 km2 and there were 47 sheets in the scale 1: 2500 and two sheets in the scale 1: 1250 used for the analyses. Data elaboration occurred on January 22, 2013 (two sheets), March 29, 2013 (18 sheets), March 30, 2013 (21 sheets), and July 13, 2013 (eight sheets).

The resulting datasets, in .LAS format as three-dimensional point clouds, are in accordance with the standard 1.2 published by the ASPRS (American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing) in 2008. Classification accuracy for points is not less than 95%. The LiDAR dataset have average point densities of 4 to 12 points/m2, with average errors estimated to 0.2 m. For the study area, with the exception of urban areas, where average points density is 4 or 6 points/m2 (standard 1), .LAS files correspond to sheets in the scale 1:2500 (1/16 of 1:10000 sheet = area of 1 × 1 km). Point spacing ranges from 0.201 to 0.419 (average 0.332) and point density for study areas (depending on sheet) ranges from 5.696 to 24.752 (average 9.968). The points were classified based on ASPRS standards: 0 – Never classified/Unclassified, 2 – Ground, 3 – Low Vegetation (0–0.40 m), 4 – Medium Vegetation (0.40–2.00 m), 5 – High Vegetation (above 2.00 m), 6 – Building, 7 – Noise, 9 – Water, 12 – Overlap. The 3D point cloud data were processed in ArcGIS 10 (3D Analyst) to create DEM from points pre-classified as 2-Ground, and the option “any return” was used. In order to extract slope from DEM, the standard tool in ArcGIS was used (Slope). The walls were digitalized manually based on the tools Hillshade and Slope in ArcGIS, and TPI Topographic Position Index for a various radius of the circle (0.5–10 m) in SAGA GIS. The density of walls was calculated in ArcGIS with the tool Calculate Geometry. There were no large water bodies within the area of stone wall occurrence so the entire surface was included in the calculations.

Measurements of Walls and Niches

During the field survey, 42 measurements of height and width of stone walls as well as ten measurements of niches were taken (Tables 1 and 2; see also Fig. 1). Measurements were taken at selected locations within the boundaries of Kopaniec, Chromiec, and Górzyniec. In these localities, the discussed field walling system is observed in its highest density and the best state of preservation. Some of the walls are currently situated in the forested area, while parts are located in areas currently used as meadows. The choice of these locations was also associated with their availability.

Measurements of walls and niches were taken using measuring tape. Wall sections that were best preserved were selected for measurement at sites where they were not damaged by tree roots, landslips, or overgrown with dense vegetation. We used a handheld Garmin GPSmap 62st device when locating measurement points. The points were subsequently plotted on maps prepared in the ArcGIS 10 program.

The width of the walls within their course, as well as their height were variable and the measurements taken are subject to a certain error rate. The coefficient of calculation of measurement errors in relation to similar constructions has been included in other works (Johnson and Ouimet 2016: 26; Thorson 2005). This error may result from the inclination of flanking aprons. However, the lack of archaeological works concerning the structures in question makes these considerations hypothetical. Also, within the walls measured in our study area, similar excavations were not carried out. It seems, however, that in many cases in the studied region, stones were laid directly on the ground. Lack of foundations meant that the stability of the walls was related to their large widths (3.9–5.6 m) and low heights (0.6–0.8 m) (see Fig. 2, Table 1).

During the field survey, ten niches built in the walls were found and measured. However, the number of niches must have been larger in the past, as some constructions could have been destroyed. This is indicated by fragmentarily preserved constructions. Archaeological verification research was done to define the function of one of the preserved niches. For this purpose we chose a construction located in a field west of Kopaniec (a plot with a contemporary no. 208/1), at an altitude of 695 m a.s.l. The niche was available and well preserved. Exploration of the interior began with cleaning and removing a thin layer of humus, under which a utility level was uncovered and investigated.

Results

The most lasting traces of harsh farming conditions in the past within the study area are numerous stone prisms and walls. Their size and forms are varied and the range of distribution was until recently rarely studied. The scarcity of research was connected mainly with limited observation possibilities in forested areas, the fact that such structures were rarely marked on archival maps, and the lack of technical means that would allow preparation of a comprehensive documentation of their location and spatial pattern. Application of data acquired through laser scanning enables us to study the range and spatial arrangement of the structures in a detailed way (see Fig. 1).

Distribution of Stone Walls

In the study area, 586 segments of stone walls were discovered, part of which previously functioned as field/plot boundaries. Now they are strongly fragmented due to the lack of repair work and the progressive degradation of the walls (see Fig. 1). Stone walls are usually situated on slopes, at altitudes of 395 to 805 m a.s.l., mostly at angles of 10–15°, up to 20°.The walls less frequently occur also on flattened areas between slopes or on ridges – in those cases the slope angle does not exceed 3–6°. The density of stone walls for the whole study area equals 2.2 km/km2, however, the distribution is spatially varied. We can distinguish two zones where the stone walls enclosing old arable lands in polygonal plots concentrate – those are areas of Górzyniec and Chromiec, Kopaniec (see Fig.1). The density of walls is much higher in these locations than in other areas and equals 5.7 km/km2and 6.8 km/km2, respectively. The walls in the area of Górzyniec are located on slopes exposed to the south and southeast, while the ones from the area of Chromiec-Kopaniec are situated on the opposite side of the Kamieniecki Ridge, on slopes exposed mostly to the north (also northeast and northwest). The areas of old fields delineated by stone walls are characterized by irregular shapes and different sizes – no regularity in their spatial distribution can be observed.

Morphometry of Stone Walls

The lengths of particular segments of stone walls in the study area are strongly differentiated and vary from merely 8 to 876 m, usually reaching from several tens to 100–120 m (the average length in the study area equals 114 m). In the highest density areas in the vicinity of Górzyniec and Chromiec-Kopaniec, the maximum lengths of wall segments equal 418 and 348 m, respectively. The walls are usually close to 100 m, just as in the entire area of analysis (see Table 1). The heights of walls in the study area range from 0.30 to 4.5 m, and their widths range from 0.5 to 7 m (see Fig. 2, Table 1).

Nevertheless, it should be stressed that the walls are characterized by considerable irregularity in terms of morphometric features and even in short fragments there might be locally narrower and broader parts. However, as in the cases observed in New England, such a wall with time, due to natural factors—but also ones related to human activities—may have been partially covered with soil. The process of soil deposition along the walls was associated with ploughing and pushing the soil towards the edge of the field. As a result, the surface of the present ground may be higher on one side of the wall (Johnson and Ouimet 2016: 26), which was observed during field survey in a few cases.

Walls in a cross-section are more similar to trapezoids than rectangles. Their base is wider than the wall top. However, this was not fully perceptible in the case of walls of very large width reaching 5–6 m and a relatively small height, where often the stones laid at the edge were not specially selected and the face of such a wall was irregular.

In the most spectacular cases, in the zone adjacent to the village of Kopaniec in the southwest, the walls reached a height of a 4.30 m and a width of 5.9 m (Fig. 3; also see Table 2).

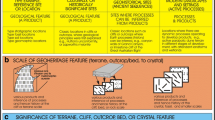

Construction of Walls and Niches

The walls are differentiated in terms of size, form, and construction technique (Fig. 4). The stones were sometimes placed at the field edges in the form of wide heaps. Some heaps have one side arranged evenly, forming a kind of ramp, which could have been helpful in unloading the material from a cart. Some walls were built in an elaborate way, resembling the opus emplectum technique (a Roman technique, but also used in Medieval and modern times in Europe). In those cases, two sides of the wall were made of larger, well-fitted stones and the void between them was filled with smaller stones. Some of them reached only a few centimetres in diameter. The largest blocks remaining in areas cleared for agricultural purposes were drilled and crushed. Traces of drilling are visible on many stones found during the field survey (Fig. 5).

Porosity of stone structures observed during the survey varied. In many cases free spaces between stones were thoroughly filled with smaller stones collected during agricultural work. Undoubtedly, the lower porosity of the walls is related to the longer time required for collecting stone from fields and successively complementing the structure (Thorson 2005).

Some walls have niches. This is unusual, as such features are unknown in other regions in the Sudetes. In the researched constructions located north of the village of Górzyniec, and also in some cases of those situated southwest of Chromiec and south of Kopaniec, there are U-shaped niches of different sizes. These walls are carefully made of hammer-shaped stones. During the field survey we noticed that one niche was usually associated with one plot. Most structures of this type were grouped in the Górzyniec area (six niches) (see Fig. 1, Table 2). Larger structures were suitable for making a temporary shelter or utility room. The largest of the recorded niches reached a depth of nearly 5.45 m, while their height was relatively short, ranging from 0.7 to 1.4 m. The biggest niches were usually located in the corners of the plots, and the walls that met there were clearly wider in that area. The smallest was recorded southwest of the village of Chromiec, in a section of a wall running in a north-south direction. It was only 70 cm high, 1.6 m deep and 1.1 m wide. It was covered with plates made of hewn stones (Fig. 6, also see Table 2: 10).

The niche west of Kopaniec, where the detailed archaeological excavation was conducted, was not located in the wall, but cut into a stone heap moved from the field border wall (Fig. 7). The heap itself had the shape of an irregular oval situated in a north-south direction, with the maximum length of 16.5 m, the width of 9.4 m, and a height reaching 2.5 m. At one of its sides there was a U-shaped niche. Faces were made of stone, forming a so-called dry wall, and the corners met at an angle close to 90°. The construction was preserved in a relatively good condition and it was presently used as a storage for branches. It was situated in the direction east-west. The southern wall was 3.3 m long, and the eastern one was 2.5 m long. The height of the walls at the highest point equalled 1.2 m. Most of the building material was crushed stone. Large- and medium-sized stones were used (0.45 × 0.31 m; 0.20 × 0.15 m).

The excavated utility level of the niche was formed of dusty humus filled with rock debris with local concentrations of charcoal. Its thickness reached as much as 20 cm, and below medium-sized rock debris gradually appeared. After the exploration it resembled a kind of foundation, but it was not paving, but rather loosely set material that formed a concise layer. In the utility level there was little archaeological material, only four pieces of stoneware from Bolesławiec/Bunzlau with brown glaze outside and white inside (Glinkowska 2012), and two fragments glazed inside, and a whetstone. The whetstone was found at the entrance to the construction. The aforementioned pottery can be dated to the turn of the nineteenth century or later.

Discussion

Functions and Conditions of Construction of Stone Walls

Mountainous areas, especially those built of crystalline rocks, are characterized by highly skeletal soils, which pose many problems for agriculture. However, due to the considerable overpopulation of villages in the study area and agricultural use of even less useful lands, it became essential to clear the arable lands of rock debris and boulders to make farming possible.

It needs to be stressed that removing rock debris is not a single procedure of preparing the land for farming, especially in the moderate climatic zone. The debris has to be constantly removed, as it appears on the surface of fields regularly as a result of both agricultural (ploughing) and natural processes (freezing of deeper parts of the ground, uncovering the debris due to erosion and washing-off smaller fractions) (see Cronon 1983; Thorson 2004). The initial function of removing rock debris was to prepare the land for farming (removing larger blocks and boulders) and afterwards – its maintenance during agricultural usage of the land (removing smaller fragments that appear on the surface later). In order not to waste the surface of arable lands for storing rocks, they were placed in less useful places (e.g., close to rock outcrops or along balks or watercourses that marked property borders and field divisions). At the same time, erecting stone walls and enclosing small fields was a good solution to protect the shallow mountain soils from wind and water erosion.

In order to realize how extensive clearing of the fields was done, one has to take a look at the forested areas of neighboring fields. There are numerous gneiss blocks and boulders whose estimated weight exceeds a few tons. In the process of preparing the land for farming, it was not enough to gather small stones from the surface, it was also necessary to crush larger blocks and boulders, transport them, and to place them in a border wall.

During a field survey conducted in the forest between the villages of Kopaniec and Górzyniec and toward a southeasterly direction, some fragments of unfinished walls have been discovered. Small prisms of stones, probably prepared for transport to the field border, were found. However, the surrounding area was not even and there are still numerous boulders on the surface. These finds prove that the preparation and recovery process was not finished in every case. Some ongoing ventures were abandoned for unknown reasons. Perhaps this was also somehow connected with the process of industrialization as new factories appeared in the region (especially in the biggest city in the region – Jelenia Góra – in the nineteenth century). New possibilities of factory work resulted in mass migration of former peasants to the cites (Walczak 1968).

At the foot of a stone heap in Górzyniec, just as in the case of the walls in the vicinity of Kopaniec, we found crushed boulders up to 2 m long. They must have been transported by a couple of people, using draft animals and appropriate constructions such as ramps and levers, especially needed when stones had to be placed high on the wall. Based on observations of unfinished fragments of walls, we assume that the process was conducted gradually. Stones were set in prisms of 2–3 m in diameter and around 1–1.5 m high, 10–20 m apart from one another, and then the gathered material was transported to the border wall or used in another way. We can presume that the stones collected in the lower parts of the village, with better transport options, were used as building material not only for those who lived in the village, but also for people from the nearest neighborhood.

The walls did not only function as borders, but were also used for other purposes, which is evidenced by the niches. The role of these structures is unclear. We can assume the largest ones were helpful in field work. They could have combined the functions of temporary storage and provisional dwelling. They could have accommodated a cart or animals inside without any problem. We know nothing about their roofs. During the study, no traces of wooden constructions of roofs or doors were recorded. It is possible, however, that the niches originally could have been covered with simple hut-like roofs that were regularly changed. Defining the function of two small niches in the vicinity of Chromiec is more difficult (see Table 1). Such a small construction could have served only as a storage place, possibly for temporary tools, food, or firewood.

A small amount of archaeological material found during the prospection of the niche in Kopaniec suggests that this site was not frequently used as a dwelling and served rather supportive functions. Traces of fire indicate that the niche was occasionally used for preparing food or providing warmth. It also served as a protection from the wind and could have been originally covered with a hut-like roof. We do not associate the construction of the niche with the time right after the field had been delineated. It is suggested among others by a regular layer of stones set against the walls of the construction. They were erected sometime after the heap had been raised. It is probable that the construction of the prism took many years and that the ancillary construction was built early. The lack of comprehensive archaeological research of other niches does not allow the determining of a more precise chronology. Possibly they are not the result of a single venture. The idea to erect niches could have been taken over by many generations of farmers and spread wherever walls were constructed. In the area of Chromiec, presently in a forest southwest of the village, there are fragments of walls with niches of similar size and with a face of the wall clearly marked on the edge. These constructions were only one or two stones high. However, we can see that they were planned very early, in the initial phase of the construction of the wall.

It is hard to clearly state whether the walls were constructed on previously delineated borders, or the borders of a future field were defined based on estimations of how much work would be needed. It is possible that the process was connected with exemptions from fees for several years and then the size of a plot depended on worktime and the number of people who were involved. In the first stage of field development, the largest stones were removed, and the foundation of the wall was laid. These stones bear traces of drilled holes and are of considerable size. In the following years, more stones were added to the wall successively collected during field works. It is the only clear evidence that some of the recorded walls were built over a long period of time. That occurred in cases of very large constructions built with the use of a lot of small stones collected successively each year after plowing.

Border stones were found within walls only in some cases. However, it is unclear whether they were placed after the wall had been erected and connected with validation of the wall or if the delineation was done at the very beginning. Further studies will be necessary to answer this question. Border stones were mainly small cuboids with a sign of an isosceles cross. The signs were sometimes carved into unworked stones. The stones were placed along walls, less often on their top. Single border stones can also be found outside these structures. Property borders delineated in this way were confirmed on official cadastral maps in the mid-nineteenth century (Fig. 8).

Stone field borders recorded in the Sudetes show how the local population was determined to deal with a deficiency of arable lands. To some extent they show tendencies that are better recognised in the British Isles and in northeastern USA. Similar phenomena occurred in the high-altitude zones of New England. According to Thorson (2005), wide, regularly shaped walls indicate that a lot of effort in a short period of time was put into clearing fields and meadows. After some time agricultural activity was stopped and the fields were spontaneously overgrown with forests due to vegetation succession (Johnson and Ouimet 2018; Thorson 2004, 2005). In the area discussed in this paper, the process was similar, although conditioned by different economic and political factors, not only industrialization but also population exchange after World War II.

It is also mentioned in the literature that walls were disappearing due to changes in agricultural techniques and the merging of small fields (Duchoslav 2002, Johnson and Ouimet 2018; Thorson 2004). The following factors are thought to have led to the decrease in profitability of agricultural production on small farms: the development of the railway, new possibilities of earning money in the western part of the country, soil depletion, mechanization, and government support (Allport 1994). However, in the study area the former agricultural areas were left entirely aside after abandonment and no modern developments have been observed. Only natural afforestation could be observed locally in these areas. Therefore, most of the old stone structures are still preserved in the landscape, and usually in a good state. It has been proven by extensive research that stone walls not only have historical value, but are also important elements of the ecosystem. Those that were constructed without mortar function as shelters and provide good conditions for many species of plants and animals (Affek 2016a; Collier 2013; Schreg 2016).

Spatial Differentiation of Size and Forms of Stone Walls and Heaps

The size of walls and their construction techniques depended on how much rock debris was on the surface. When there was little debris, it was enough to gather it and form a prism or a loose wall. But when there was more debris and large boulders and blocks, more effort was necessary and walls up to a few meters were carefully constructed.

The occurrence of stone fences enclosing fields can be clearly associated with higher and steeper parts of slopes, and further location from buildings, while walls that did not form closed fences are more common in areas situated at lower altitudes and gentle slopes, directly next to human dwellings. It might be connected on the one hand with more intensive water and wind erosion on slopes where the slope angle exceeds 10° and at higher altitudes, which required more effective solutions that would provide protection for the soil cover. Moreover, higher and steeper parts of the slopes are generally connected with a thicker layer of debris in the Sudetes. Lower parts of slopes and flattened foothills and valleys, in which fine-grained fraction material accumulate, have a lower percentage of boulders and blocks, and that is why preparation for farming did not require the removal of such large amounts of rock material as in the higher parts of slopes.

The size and density of the distribution of stone walls and prisms can also be associated with the lithology of the geological substratum. In contrast to some other regions, for example, the northeast of the USA, where the walls were largely built from stony material from glacial till (Johnson and Ouimet 2016; Thorson 2004, 2005), the study area was never glaciated in the Quaternary (Migoń 2005). However, it was subject to a periglacial climate in that period, which favored an intensive mechanical weathering of rocks due to frost action. It contributed to the formation of extensive block covers on slopes, which later became the source of building material for walls. While the bedrock lithology is generally homogenous in the study area, there could have been variations in the abundance of rock debris in the slope/soil cover related to former bedrock outcrops and the intensity of its weathering. It results nowadays in an uneven distribution of wall densities and sizes. Morphometric analyses conducted in other parts of the Sudetes, on different types of geological substrata (gneisses, granites, sandstone, mica schists) clearly indicate that the largest stone structures are connected with the occurrence of gneisses in the bedrock (Latocha 2012, 2014). Outside the Izera Mountains the largest constructions were identified in the Bystrzyckie Mountains in the central Sudetes, also based on gneisses. Walls in that area are up to a few hundred meters long, up to 1.4 m high and 5–6 m wide, while heaps are up to 30 m long, up to 20 m wide and up to 2–3 m high (Latocha 2012). Nevertheless, they never formed closed fences as occurred in the study area.

Chronology

The distribution of stone walls preserved in the zone neighboring on the south of the villages of Antoniów, Chromiec, Kopaniec, Kopanina, and north of Górzyniec, reflect the topography of fields organized in the period of demographic growth and the need to extend the surface of arable lands. Intensive adaptation of wastelands for the needs of agriculture can be dated to the modern period (seventeenth–nineteenth century), namely right after the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), or to industrialization that started in this area in the second half of the nineteenth century and provided alternative money-earning opportunities for the local population and the extensive outflow of inhabitants of mountain villages. The shifts of political borders and the exchange of population after 1945 additionally enhanced the process of permanent abandonment of many fields.

In order to establish the chronology of wall construction we should also have information on the initial forest clearances. However, we do not know what part of the area was covered with forests. It seems that it was deforested earlier in the period when forest glassworks requiring large amounts of fuel were active (ca. 1330–1400). The species composition in the forests surely changed at that time. The demand for beech wood caused the need to replace it with different species. Unlike many other areas in the world, where deforestation occurred as a result of agriculture (i.e., in the northeastern part of the USA; see Johnson and Ouimet 2016; Thorson 2004), forest cutting in the Sudetes Mountains was primarily related in many areas to glass manufacturing. The resulting open areas were only subsequently occupied by agriculture (Walczak 1968).

Conclusions

The aim of this paper is to give a comprehensive presentation of the stone walls in the Izera Mountains in the southwest of present-day Poland, including their morphometric characteristics. We also attempted to determine their origins, functions, chronology, construction techniques, and their significance for the regional cultural landscape. Partially, these goals have been realized, but there are still many questions requiring solutions. It is especially necessary to clarify the chronology and the time of wall formation in a more detailed way. With the current state of our knowledge, we can only presume that the construction of the walls was a long process over many generations. It can be related to the phase of maximum population and settlement development in the mountain regions, which was between the seventeenth and nineteenth century. This sudden population growth caused land hunger and expansion of agriculture even on less fertile and stony soils, located above 550 m a.s.l. The joint research methodology, combining field surveys, archaeological excavations, analysis of old cartographic sources, and LiDAR data, has allowed us to draw some conclusions on the spatial diversification of stone wall distribution and their morphometric features, as well as their functions and conditions of construction.

Stone walls in the study area served different, mostly combined, functions: they marked field boundaries and property divisions, protected the arable lands from water and/or wind erosion, and they were a “side-effect” of work connected with removing rock debris and boulders from areas intended to be occupied for agricultural purposes. A series of measurements and observations showed that the walls differ spatially. These differences of size and design are significant, which seems to confirm the view that they were not created at one time. Some of them are extremely wide and high. The differences in density and size of the walls can be attributed to the local environmental conditions, such as an uneven abundance of rock debris in the slope covers, elevation, and slope angle. Additionally, these differences might also be related to past land ownership and land divisions. However, the currently available archival data does not provide enough evidence to support this assumption and further investigation of archival sources should be conducted. There is also a need for further extensive archaeological excavation within the niches, which are a unique landscape feature of the wall system. The niches are found in small numbers, but they constitute interesting constructions of an uncertain origin, purpose, and time of construction. Undoubtedly, some of them served economic purposes (possibly storage), but no traces of longer use were found during the excavation of one of them. A small number of artifacts indicates rather that they were used seasonally, for a short time and not for dwelling purposes.

Presently, stone constructions can be regarded as valuable elements of the cultural landscape that are evidence of different land use, including a significantly larger surface of arable land in the past. These constructions, built with great effort, are unique historical monuments worth protecting. Knowledge of them should be passed on, especially because stone walls enclosing fields are rare in the mountainous areas of Central Europe. Additionally, the lack of any modern development of the study area after its abandonment several decades ago, allowed for good preservation of the wall structures, another exceptional attribute. They can be perceived as relics remnant of former land use and the past economy of mountain inhabitants, related to the history of settlement development and, in general, the intensification and the further decline of the human impact on the landscape. The many uncertainties regarding the surveyed walls and stone structures, mean that they are an inspiring subject for further study.

References

Adamska, D. (2016). Siedlęcin, czyli „wieś Rudigera”. Studia nad średniowiecznym osadnictwem wokół Jeleniej Góry. In Nocuń, P. (ed.), Wieża książęca w Siedlęcinie w świetle dotychczasowych badań - podsumowanie na 700-lecie budowy obiektu. Profil-Archeo, Pękowice, pp. 37–73.

Affek, A. (2016a). Hidden cultural heritage in the abandoned landscape – Identification and interpretation using airborne lidar. Geographia Polonica89(3): 411–414.

Affek, A. (2016b). Past Carpathian landscape recorded in the microtopography. Geographia Polonica89(3): 415–424.

Allport, S. (1994). Sermons in Stone: The Stone Walls of New England and New York. W. W. Norton, New York.

Bennett, R., Welham, K., Hill, R. A., and Ford, A. (2012). A comparison of visualization techniques for models created from airborne laser scanned data. Archaeological Prospection19: 41–48.

Bernardini, F., Sgambati, A., Montagnari Kokelj, M., Zaccaria, C., Micheli, R., Fragiacomo, A., et al. (2013). Airborne LiDAR application to karstic areas: the example of Trieste province (North-Eastern Italy) from prehistoric sites to Roman forts. Journal of Archaeological Science40: 2152–2160.

Bewley, R. H., Crutchley, S. P., and Shell, C. A. (2005). New light on an ancient landscape: LiDAR survey at the Stonehenge world heritage site. Antiquity79: 636–647.

Biermann, F. (2010). Archäologische Studien zum Dorf der Ostsiedlungszeit. Die Wüstungen Miltendorf und Damssdorf in Brandenburg und das ländliche Siedlungswesen des 12. bis 15. Jahrhunderts in Ostmitteleuropa. Brandenburgisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologisches Landesmuseum, Wünsdorf.

Challis, K., Forlin, P., and Kincey, M. (2011). A generic toolkit for the visualization of archaeological features on airborne LiDAR elevation data. Archaeological Prospection18: 279–289.

Chase, A. F., Chase, D. Z., Weishampel, J. F., Drake, J. B., Shrestha, R. L., Slatton, K. C., et al. (2011). Airborne LiDAR, archaeology, and the ancient Maya landscape at Caracol, Belize. Journal of Archaeological Science38: 387–398.

Chorowska, M., Duma, P., Furmanek, M., Legut-Pintal, M., Łuczak, A., and Piekalski, J. (2017).Wleń/Lähn District in the Sudetes foothills, Poland: a case study of cultural landscape evolution of an east central European settlement micro-region from the tenth to the eighteenth centuries. International Journal of Historical Archaeology21(1): 66–106.

Collier, M. (2013). Field boundary stone walls as exemplars of “novel” ecosystems. Landscape Research38(1):141–150.

Cronon, W. (1983). Changes in the Land. Hill and Wang, New York.

Defining Stone (2007). Defining stone walls of historic and landscape importance, Final Report produced for Defra and partners by Land Use Consultants with AC Archaeology, April 2007. <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/320858/Defining_stone_walls_of_historic_and_landscape_importance.pdf>. Accessed August 2018.

Detailed Geological Map of Sudetes 1:25,000 (2004) Polish Geological Institute, Warsaw.

Duchoslav, M. (2002). Flora and vegetation of stony walls in East Bohemia (Czech Republic). Preslia74: 1–25.

Forejt, M., Dolejš, M., and Raška, P. (2018). How reliable is my historical land-use reconstruction? Assessing uncertainties in old cadastral maps. Ecological Indicators94(1): 237–245.

Glinkowska, B. (2012). Analiza formalna ceramiki ze stanowiska przy ul. Piaskowej w Bolesławcu. In Glinkowska, B., Krabath, S., Bober-Tubaj, A., Bojanowska, A., Karpiński, M., Olejniczak, A., Orawiec, T., Puk, A., and Szwed, R. (eds.), U źródeł bolesławieckiej ceramiki. Von den Anfängen der Bunzlauer Keramik, Moniatowicz Foto Studio, Bolesławiec, pp. 31–203.

Hartmanová, O. (2005). Budní hospodářství v Krkonoších z pohledu archeologie. Památky Archaeologické96: 165–204.

Ivanišević, V., Veljanovski, T., Cowley, D., Kiarszys, G., and Bugarski, I. (eds.) 2015. Recovering Lost Landscapes. Institute of Archaeology, Belgrad.

Johnson, K. M. and Ouimet, W. B. (2016). Physical properties and spatial controls of stone walls in the northeastern USA: implications for Anthropocene studies of 17th to early 20th century agriculture. Anthropocene15: 22–36.

Johnson, K. M. and Ouimet, W. B. (2018). An observational and theoretical framework for interpreting the landscape palimpsest through airbone LiDAR. Applied Geography91: 32–44.

Kaim, D., Kozak, J., Ostafin, K., Dobosz, M., Ostapowicz, K., Kolecka, N., and Gimmi, U. (2014). Uncertainty in historical land-use reconstructions with topographic maps. Quaestiones Geographicae33(3): 55–63.

Klápšte, J. and Sommer, P. (eds.) (2009). Medieval Rural Settlement in Marginal Landscapes. Ruralia VII. Brepols, Turnhout.

Kondracki, J. (2002). Geografia regionalna Polski. PWN, Warszawa.

Latocha, A. (2009). The geomorphological map as a tool for assessing human impact on landforms. Journal of Maps5(1): 103–107.

Latocha, A. (2012). Przemiany społeczno-gospodarcze i przyrodnicze doliny Dzikiej Orlicy w okresie powojennym. Orlicke Hory a Podorlicko19: 85–106.

Latocha, A. (2013). Wyludnione wsie w Sudetach. I co dalej? Przegląd Geograficzny85(3): 373–396.

Latocha, A. (2014). Geomorphic connectivity within abandoned small catchments (Stołowe Mts, SW Poland). Geomorphology212: 4–15.

Łuczyński, R., Migoń, P., and Napierała, P. (2015). Krajobraz kulturowy rejonu Kotliny Jeleniogórskiej. Fundacja Doliny Pałaców i Ogrodów Kotliny Jeleniogórskiej, Wrocław.

Madziarz, M. and Sztuk, H. (2006). Eksploatacja rud cyny w Górach Izerkich: historia czy perspektywa dla regionu? Prace Naukowe Instytutu Górnictwa Politechniki Wrocławskiej. Studia i Materiały 117(32): 193–202.

Manenti, R. (2014). Dry stone walls favour biodiversity: a case-study from the Apennines. Biodiversity and Conservation23(8): 1879–1893.

Marshall, E. J. P. and Moonen, A. C. (2002). Field margins in northern Europe: their functions and interactions with agriculture. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment89: 5–21.

McAfee, P. (1997). Irish Stone Walls: History, Building, Conservation. O'Biren Press, Dublin.

McNeary, R. W. A. (2014). LiDAR investigation of Knockdhu promontory and its environs, County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Archaeological Prospection21: 263–276.

Migoń, P. (2005). Rozwój rzeźby terenu, [in:] J. Fabiszewski (ed.), Przyroda Dolnego Śląska, PAN, Wrocław, pp. 135–170.

Migoń, P. (2012a). Granit – od magmy do kamienia w służbie człowieka. W granitowym świecie zachodnich Sudetów, Karkonoski Park Narodowy, Jelenia Góra.

Migoń, P. (2012b). Z geomorfologii Sudetów (55): bobrowe Skały. Sudety130(1): 26–29.

Migoń, P. and Latocha, A. (2018). Human impact and geomorphic change through time in the Sudetes. Central Europe. Quaternary International470(A): 194–206.

Opitz, R. S. and Cowley, D. C. (eds.) (2013). Interpreting archaeological Topography: Airborne laser scanning, 3D data and ground observation. Oxbow Books, Oxford; Oakville CT.

Regesty Śląskie (1975). Regesty Śląskie, t. 1: 1343-1348. Bobowski, K., Gilewska-Dubis, J., and Turoń, B. (eds.). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, Wrocław.

Schreg, R. (2016). Mittelalterliche Feldstrukturen in deutschen Mittelgebirgslanschaften – Forschungfragen, Methoden und Herausforderungen für Archäologie und Geographie. In Klápšte, J. (ed.), Agrarian Technology in the Medieval Landscape. Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, Ruralia X, pp. 351–370.

Soil agricultural map at a scale of 1:25,000 (2004). Polish Geological Institute, Warsaw.

Spurný, M. (ed.) (2006). Proměny sudetské krajiny. Antikomplex, Domažlice.

Staffa, M. (ed.) (1989). Słownik geografii turystycznej Sudetów, 1, Góry Izerskie. PTTK „Kraj”, Warszawa-Kraków.

Szymańska, D. (2013). Geografia Osadnictwa. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

Thorson, R. M. (2004). Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New. England’s Stone Walls, Bloomsbury, New York.

Thorson, R. M. (2005). Exploring Stone Walls: A Field Guide to Stone Walls, Walker, New York.

Walczak, W. (1968). Sudety. PWN, Warszawa.

Wolski, J. (2007). Przekształcenia krajobrazu wiejskiego Bieszczadów Wysokich w ciągu ostatnich 150 lat (Vol. 214). Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN, Warszawa.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written as part of the project “Adaptation of settlement and economy to the marginal conditions of the natural environment. Development of cultural landscape of the western Sudetes from the Middle Ages to the mid-20th century” funded by the National Science Centre (Agreement no. UMO-2015/19/B/HS3/01752). The authors would like to thank Leszek Różański for showing us some of the mentioned stone walls and niches. The authors are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the editor for very helpful comments that have allowed us to improve the initial version of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Duma, P., Latocha, A., Łuczak, A. et al. Stone Walls as a Characteristic Feature of the Cultural Landscape of the Izera Mountains, southwestern Poland. Int J Histor Archaeol 24, 22–43 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00501-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00501-2