Abstract

Creativity is an important goal for higher education yet there is limited guidance on how to facilitate it at an organisational level. This arts-based exploration of the experiences of three award-winning academics who have been recognised for their creative work identifies that creativity can emerge from three interrelated factors — conversations and relationships, liminal space and leadership. These factors combined form a useful model that offers higher education institutions a means for enhancing creativity at a time when arguably it has never been needed more. The three factors are easily articulated, not resource-dependent or contingent on specialist knowledge or skill and will likely be well accepted by academics, academic leaders and others who participate in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Educators and researchers agree that creativity in higher education is relevant (Jahnke & Liebscher, 2020). It is the basis of discovery (Tanggaard, 2018), considered a key skill for twenty-first century learning (Egan, et al., 2017) and is drawn on in times of stress, for example during the current COVID pandemic (Mercier, et al., 2021). It would be reasonable to argue, as Tosey (2006) foretold, that there has not been a time when higher education needs creativity more. This is not only because of COVID; the concern goes even deeper than that and includes the neoliberal project that higher education has been drawn into. Here is an issue that has implications for not only students and academics, but for higher education institutions and government authorities, as well as the industries and communities that higher education serves. How can creativity, a concept for which no precise meaning exists (Gilmartin, 1999), be thought about and facilitated in higher education? This is the question addressed in this research, a question directed at an organisational level — the university level.

To think differently about creativity requires one to go beyond the so called ‘interactionist approach’, where individual creativity cascades into group creativity, which in turn cascades into organisational creativity (Woodman et al., 1993). One also has to go beyond, say, how to develop students’ creativity, as has been discussed by Norman Jackson and Christine Sinclair (2006), or how to assess students’ creativity, which has been dealt with by John Cowan (2006), or how to develop academics to teach more creatively (Wisdom, 2006). Here I am interested in what Andrew Hargadon and Beth Bechky describe as the ‘fleeting coincidence of behaviours that triggers moments [original emphasis] when creative insights emerge’(2006) — a ‘supraindividual’ (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006) or perhaps ‘supragroup’ or ‘supreinstitutional’ perspective, though I should declare my reservation about Hargadon and Bechky’s ‘moments’ as times when creativity emerges, which may merely be when creativity surfaces and becomes visible, out of a process of continual development.

To think differently about creativity also requires a fresh starting point, one unencumbered by tradition or stifled by traditional research methodologies. I start this exploration with a mental picture of creativity in organisations based on the image of the sea. I use a ‘sea of creativity’ (Rae, 2018) metaphor to help think about organisational creativity, including creativity in higher education. I imagine movements of water molecules creating waves that are the sea; not just something passing over it. In the same way, ‘creativity does not happen at the edge but in the reconfiguration of the centre itself’ (Moran, 2009). So, in the higher education institution, and no doubt other types of institutions, creativity would be considered omnipresent. The beach, where the waves meet the less yielding aspect of an organization, that is, the shore, is betwixt and between, or liminal. This is where these ‘moments’ of creative insights are triggered (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006).

Methodology and Methods

This research draws from Margaret Somerville’s concept of postmodern emergence (Somerville, 2007) and relatedly, her epistemology of ‘generating’ and ontology of ‘becoming’, which fit well with my practice of using art to think differently about concepts such as creativity, in this case creativity in higher education. Art is ‘well-positioned to provide deep understanding of higher education’ (Metcalfe and Blanco, 2019) and offers a critical perspective and a means for resistance at a time when, as Catherine Manathunga et al. (2017) argue, ‘the spaces of collegiality, pleasure and democracy in the measured university are under attack’. That said, arts-based methods help to defamiliarize the lived experience of academic life (Mannay, 2010) and this is important because I am also a participant in higher education.

I appreciate the generative qualities of art that offers ‘an iterative process of representation and reflection through which we come to know in research’ (Somerville, 2007). The notion of ‘becoming’ is also important here because ‘becoming-other’ is a ‘condition for generating new knowledge' (Somerville, 2007), sometimes through inanimate objects such as paper, paints, brushes and wax ‘that we humans have chosen to use to create’(Somerville, 2007).

I want to understand academics’ perspectives on creativity, so I selected and interviewed three academics from a single Australian university who had received national awards for their novel and useful work, two criteria of creativity (Amabile & Mueller, 2008). I postulated that if creativity is in fact omnipresent, getting back to the sea of creativity, I may be able to ‘trap [it] in the wild’, or more appropriately, better understand and facilitate it. With human ethics committee permission, and a decision to use pseudonyms to preserve anonymity, I met up with Richard Chatterfield who received an award for his academic leadership, Jane Strickland, similarly recognised for her work in pedagogy and the fact that she developed a virtual environment to teach fire investigation, and Stuart Truman who had a highly regarded approach to teaching philosophy. In fact, I had two conversations with Richard, Jane and Stuart. Between each of the first and second conversations I made artworks and I took these back at each of these second interviews. This allowed me to probe deeper and to decontextualise and recontextualise the participants’ ideas so that new families of association and structures of meaning (Carter, 2007) were established.

Metaphor assisted here too; the ‘partial and ambiguous applicability to the object of study stimulates theory builders to be creative in their interpretations and to generate new insights’ (Boxenbaum & Rouleau, 2011). This practice goes back to Aristotle who observed how metaphors can offer fresh understandings, in a way that ordinary words cannot (as cited in Miller, 1996). In this study, art and metaphor were used together. Both were useful generative devices, individually and collectively. They also helped to render the research materials – transcript material or research notes – ‘strange’, referring back to Paul Carter (2007). In this way, arguments challenged each other, contradictions and generalisations were identified, complexities of dichotomies were disentangled, alternative readings were sought and marginalised voices (Grbich, 2012) were acknowledged.

Findings

When I carefully reviewed all six transcripts (two for each of the three participants) I found that there were four interrelated themes that could be used to understand and potentially facilitate the process of creativity in higher education. These themes were academics in conversation, scholarly relationships, liminal spaces, and academics as leaders for creativity.

Academics in Conversation

These things are often a convergence of different conversations around different tables ... each time you have a conversation with someone, who’s in a position of influence, they’re influencing you, you’re influencing them, and collectively you contribute to that sort of messy discourse that leads to the outcome (first interview with Richard Chatterfield).

This comment by Richard Chatterfield relates to his development of a strategic plan for learning and teaching and illustrates how such work evolves through discourse: ‘That’s where new projects are sort of, have their beginnings in those sorts of conversations’ said Richard at our first interview, and this would not be the first time that organisational creativity and conversation have been linked. Paul Tosey, coming from a complexity science perspective, considers creativity to be ‘a process through which locally developed new ideas and practices become engaged in, and are taken up through wider conversations’ (Tosey, 2006). A similar claim has been made about the importance of conversations for organisational innovation (Monge, et al., 1992), which is the actual implementation of creative ideas (Bourguignon, 2006). Conrad Kasperson has explored the association between creativity and conversations amongst scientists too, which he claims is related to ‘the utility of people at conventions, meetings, and the like’ (1978). He wrote that ‘creative scientists are distinguished from other scientists in their use of people as sources of information and [because] they receive information from a wider field of disciplinary areas’(1978, p. 691).

This link between creativity and conversation can be understood in a variety of useful ways. For example, Vlad-Petre Glaveanu (2011) used a sociocultural frame:

The person is guided in his/her creative process by a broad cultural frame which is the personal representational space …. By exploring/communicating these unique representational spaces members come to “realize” other ways of understanding or doing things. It is by communicating or sharing such resources (in the form of ideas, experiences, procedures, etc.) that unique representational spaces open themselves (although never completely) to the common representational space. This “fusion” facilitates the emergence of a new representational space, the space of the creative solution (action or material outcome)’ (2011)

Glaveanu’s (2011) new representational space resonates with the concept of the ‘third space’ (or third man) that French philosopher Michel Serres (1982) wrote about in The Parasite. Here two people have a conversation, differences or disagreements emerge and a new space is required where the relationship is intercepted, and mediation occurs. Another frame from which Richard Chatterfield’s comments can be considered is through the work of Andrew Hargadon and Beth Bechky (2006) who underscore the importance of social interactions to organisational creativity. Hargadon and Bechky (2006) draw on the work of Teresa Amabile (1988), Andrew Van de Ven (1986), Karl Weick (1979), and Hargadon and Sutton (1997) and take the view that ‘creative solutions are built from the recombination of existing ideas’ (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006) through help seeking, help giving, reflective framing, and reinforcing (2006). Paul Schepers and Peter van den Berg add that ‘Knowledge sharing fosters creativity because it exposes employees to relevant feedback and to a greater variety of unusual ideas (2007)’. In a similar vein: ‘communication in social networks expose people to new knowledge that enables them to create radical concepts and transform them to workable technologies’(Grieve, 2009).

Social interactions, personal representational spaces, recombining existing ideas and enhancing opportunities for new knowledge are all helpful approaches for locating Richard’s comments about conversations and creativity conceptually, but here it was more important to explore Richard’s line of reasoning. I did this by making a water colour triptych (Fig. 1) that depicted Richard in conversation with a colleague.

As Richard and I examined this picture at a second interview, he commented:

We meet at conferences and stuff quite often as well so we’ll often — we’ve probably had a beer in lots and lots of different locations looking out at something. But then at the same time we’re also looking inwards, I guess, at common research problems. And that — so it’s sort of a shared visual experience but also a shared conceptual experience that brings the ideas out, I guess.

As I contemplated Richard’s words, I recalled that in assembling the triptych I came to understand that these conversations must rely on something deeper — relationships, which is a concept apparent in most of the theoretical frames already referred to here: intercepted relationships (Serres, 1982), knowledge sharing (Schepers & van den Berg, 2007), help giving (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006) and social networks (Grieve, 2009).

Scholarly Relationships

It looks as though — it looks a bit as though the two — there’s a relationship between the two figures of either sides. And so maybe there’s something in that landscape in the middle that’s connecting two people together (second interview of Richard Chatterfield).

Productive conversations deepen relationships and deeper relationships link with shared experiences ‘because you’re both in that space’ (second interview with Richard Chesterfield). Of course, these conversations and relationships are not simple linear interactions as much as a ‘network of multiple projects in terms of the research and different combinations of people’ (second interview with Richard Chesterfield). Relationship, then, is an important extension to the notion of ‘conversation’ as facilitators of creativity. Visions are shared through conversations, becoming ‘shared visions’, and as Richard pointed out, ‘if there is a shared vision it emerges through the conversation rather than existing in advance’ (second interview with Richard Chatterfield). This, according to Richard, is different from grand visions. That is:

There isn’t a grand vision and organisations don’t operate through a grand vision. And even if somebody thinks they do, actually they don’t because not everyone buys into the grand vision. Not everyone interprets the grand vision the same way. And it’s the nitty gritty things going on in all the different parts of the organisation. Those sorts of conversations playing out that results in change rather than the grand vision.

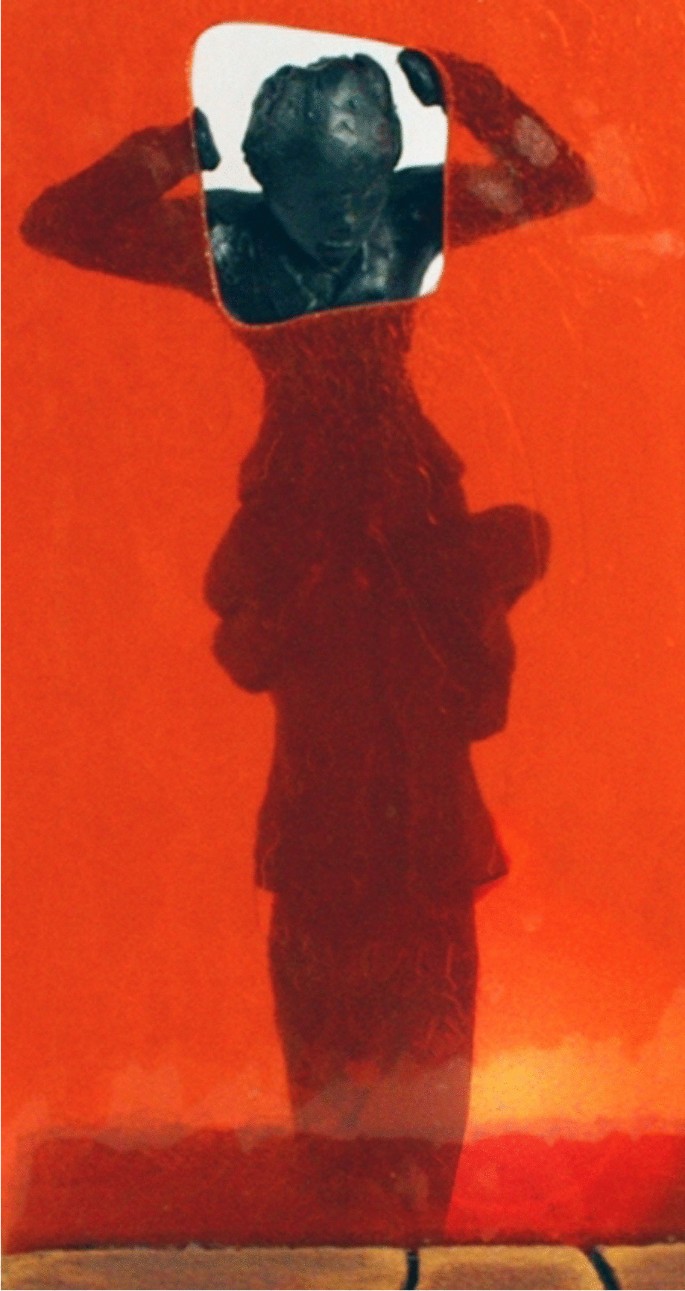

The next step was to consider the extent that Richard’s story resonated with the discussions I had with the other participants, including Jane Strickland. Following on from my initial interview with Jane I prepared a small sculpture in wax (Fig. 2) that was intended to represent her experiences developing a tool to teach fire investigation by creating footage of an actual house fire. I had hoped that synergies between the materiality of the wax and other media that I was using, along with my memories of my discussion with Jane, might lead to some fresh insights about creativity.

The original idea for this sculpture was established almost immediately after my first meeting with Jane, and as I made notes which are reproduced below.

I had fairly early on a view that it would be Jane perhaps climbing through, but then later peering through, a window, and this would be a window of a house on fire and that window would be contained in a sheet of glass - thick glass, perhaps tinted orange to represent fire and that way you would be able to see through the glass and observe the sculpture from the other side of the glass as well. Jane would be supported, peering through the window by a colleague dressed in fire-fighting overalls. The sculpture would be done in wax and glass.

The sculpture created a platform from which I could question Jane in more detail about her creativity. When I went back to see her for the second interview, Jane responded to my sculpture enthusiastically. The focus on the artworks seemed to have created a much more engaging, and perhaps less threatening, climate for this subsequent conversation. The sculpture, and especially the window that the subject of the sculpture was peering through (see Fig. 2), posed a question to Jane, to which she responded:

That tells me, that's fire …. I'm not looking into the fire; I'm looking through the fire to what's going to be on the outside …. okay, I went to that, the burning of the house, I went to the fire, but what was important to me was, what was this going to be used for, and what was going to happen on the other side of that?

I was taken by how Jane spoke about her collaborators, and when I considered the stories of both Richard and Jane together, it was other people who featured heavily. However, where Richard spoke about conversations and relationships, Jane spoke about relationships and faith:

I feel like, when I look at the sculpture I'm on somebody else's shoulders and the somebody else is somebody who has faith in me, and therefore is prepared to lift me up and allow me to see through that window — but I also have faith in them because I'm sitting on their shoulders …. so we’re standing on firm ground, and I guess the analogy there is, I'd be standing on firm ground in the sense that, I had faith in those that were guiding me, and my school, and those people around me had faith in what I was going to produce, so that's about that solid foundation.

Jane’s notion of ‘faith’ fits with, and even expand upon, Subrata Chakrabarty and Richard Woodman’s (2009, p. 192) types of creative relationships. Chakrabarty and Woodman identified four such types — no creative relationship, inspiring relationships, integrating relationships (actors mutually divide their roles for creative action) and synergysing relationships, which are characterised by ‘intense collaborative action’ (2009) that ‘encourage[s] each other’s progress, affirm[s] confidence in each other’s capability and arouse[s] mutual interest’ (2009). Synergising relationships must surely include an element of faith, or some similar emotion. Indeed, the inclusion of an emotional component such as this, according to Deborah Munt and Janet Hargreaves (2009), is in fact a characteristic feature of creativity. This might at first glance seem at odds with the work of Jill Perry-Smith who found that ‘weak ties facilitate creativity and that strong ties do not’(2006), on the basis that weak ties are characterised by ‘low levels of closeness and interaction’ (Perry-Smith, 2006) and are considered to be associated with nonredundant information, more diverse perspectives, and less conformity (Perry-Smith, 2006). However, one can argue that relationships cannot be satisfactorily categorised in such binary terms, like ‘strong’ or ‘weak’. There must be gradations of relationship strength, even a waxing and waning. The creative relationships that Richard Chatterfield spoke of could be described as weak in the sense that it was outside his immediate network, yet strong in other regards. It is likely that an element of faith, or trust, as Barbara Lombardo and Daniel Roddy (2011) put it, exists in such an apparently synergistic creative relationship. Anna BrattstrÖm et al. (2012), through their empirical research, showed that in their case, ‘goodwill trust’, that is, trust in the moral integrity of, say, a collaborator, is a mediating factor of creativity.

Stuart Truman, another participant, also referred to conversations when he spoke about his practice of teaching philosophy:

Each person’s progress is connected with every other person’s progress, so that it’s a synthesis as well as a whole lot of individual things.

Stuart is talking here about students’ learning through conversation, which parallels the creative path that Richard and Jane spoke of. This hints at some common ground between creativity and learning, and organisational creativity and the learning organisation, as has already been noted by Palmira Juceviciene and Ieva Ceseviciute (2009) and also the European University Association (2007).

Liminal Spaces

Recalling the sea of creativity metaphor, the beach emphasises the betwixt and between — the liminal: ‘parts of it are successively revealed and then swamped by tidal action’(Mack, 2011), akin to fusion and emergence (Glaveanu, 2011), a factor of creativity (Govan & Munt, 2003). This describes many higher education environments as new partnerships develop, when leadership changes, where academics work across networks, disciplines, research groups or institutions, and where diversity is embraced, which is something that has also been associated with creativity in higher education (European University Association, 2007).

My conversation with Jane Strickland led me to believe that she was also in a liminal space:

The whole project was just about stepping inside and some of that was stepping outside a comfort zone, and stepping inside, because this was going to be a whole new world to me …. I was stepping into a world that I didn’t actually know a lot about.

It was my interviews with Stuart Truman that really highlighted the place of liminality in this discussion about creativity in higher education. Stuart explained to me how he is able to straddle the ‘world of ethics’ and the ‘practical world’:

I've always been a bit of a fish out of water [emphasis added] in philosophy because I'm not a philosopher’s philosopher in the sense that I don’t love doing esoteric philosophy at the expense of everything else. I've always been just as much at home in the practical world as in the very academic world, but I've had a concern with connecting the two worlds.

When I pressed Stuart to talk about any advantages of this, he offered the following:

The disadvantage is that you don’t have an exact niche in either place but it does mean you can have a foot in both worlds or both camps and that means you're not a bad bridge builder across them, whereas the very focussed medic thinks don’t waste my time on philosophy, or the very focussed philosopher who doesn’t want to soil their mind with these practical concerns — neither of them would be well placed to do that bridge building exercise.

To explore Stuart’s ‘fish out of water’ analogy, I made a watercolour painting that featured fish cut-outs that were placed against a rich yellow background (Fig. 3).

I showed this to Stuart at our second meeting where he described ‘abstracts of swirl and sort of a cloud of both confusion and chaos and possibility’. I was able to use this metaphor as a prompt to further our discussions about being ‘betwixt and between’ as an academic. This elicited the following comment from Stuart:

There is an inherent discomfort in that position but it’s a discomfort which is essential to a certain kind of job that if I were more comfortably in one place or the other, I wouldn’t be able to play the role that I do play. Now I think all of us to some extent are that way. I think I am just a bit more than some in having a foot firmly in both of those areas.

Stuart seemed clear about the benefits of his liminal state, saying at our second interview that it was ‘useful for making connections to people who don’t live in that world’ and that ‘there can be a fertility from each direction’. This word ‘connection’ took my thoughts back to my interview with Richard Chatterfield when I first realised how vital conversations are as a means of connecting people, forming relationships and facilitating creativity. I observed too that whilst Stuart and Richard had used similar terms, they applied them to different organisational levels — Stuart spoke of the student-academic context and Richard referred to the organisational level. And in terms of the nature of these connections, Stuart made the following point:

I’ve found that the most useful discussions were with people that I got quite close to as colleagues, even as friends because then there was the level of sort of trust and openness that was really useful for deep conversations about these things.

So here the word ‘trust’ gets used again, taking us back to Glaveanu (2011) and noting that: ‘Simply putting people together never guarantees that these processes will take place’ (2011). This also takes us back to the importance of relationships, and Stuart provided me with an illustration of how relationships do matter:

If you put a surgeon and a philosopher in the same room you may find that the pure philosopher isn’t terribly enamoured by the surgeon and the surgeon certainly isn’t particularly enamoured with the pure philosopher who thinks that this person has nothing to offer that’s of any significance to his or her professional pursuits and there’s a complete lack of connection — but if, as I’ve done, you actually get to know some of these guys and to the point where you develop a real level of familiarity and trust and sharing of things., there are all sorts of possibilities.

Apart from further challenging the idea that strong ties limit creativity, this comment of Stuart’s suggests that liminality associated with relationships between people who have dissimilar backgrounds or viewpoints can be very productive. It also serves to highlight the interrelatedness of conversations, relationships and liminality.

‘Possibilities’ was a term used by both Stuart and Richard and this is something that can be linked to a psychological approach to creativity and in particular, divergent thinking (Russ & Fiorelli, 2010). Of course, taking an imagined possibility to creative action does require leadership.

Academics as Leaders for Creativity

I'm the learner and the leader. The learner because it is all new to me, and I am being guided by experts in various areas — but the other side of it is I'm the leader because this is new to them as well, and I'm saying this will be okay, look I can do this, so you can too (second interview of Jane Strickland).

This comment by Jane Strickland took my thinking another step forward. She added a dimension that was still within the realm of relationship but more about the attitude that creative leaders adopt regarding relationships. Linking creativity and leadership is not unusual; creativity is often thought to be an attribute of effective leadership (Cook & Leathard, 2004; Sternberg & Vroom, 2002). However, what Jane was saying was that the process of creativity requires leadership. To return to our sea of creativity metaphor again, creative actors must also be navigators. This is in fact something that creativity scholars (DiLiello & Houghton, 2006; European University Association, 2007; Mumford et al., 2002; Shalley & Gilson, 2004) have already highlighted. Arménio Rego, Filipa Sousa and Miquel Marques found that ‘authentic leadership predicts employees’ creativity, both directly and through the mediating role of employees’ psychological capital’ (2011). Authentic leadership comprises self-awareness, balanced processing (visible objective decision making), an internalised moral perspective (high standards for moral and ethical conduct and actions that are congruent with this), and relational transparency (an open and authentic self), as well as psychological capital that comprises self-efficacy, optimism, hope and resilience (Rego et al., 2011). Min Basadur (2004) helps out here too by broadening the discussion and differentiating between leading process and leading content:

a process leader keeps track of ‘how’ the group works on a problem. What is the flow of the process steps and what behaviours and attitudes are needed to make the flow work? The process leader’s job is to help everyone work together toward a useful solution (2004).

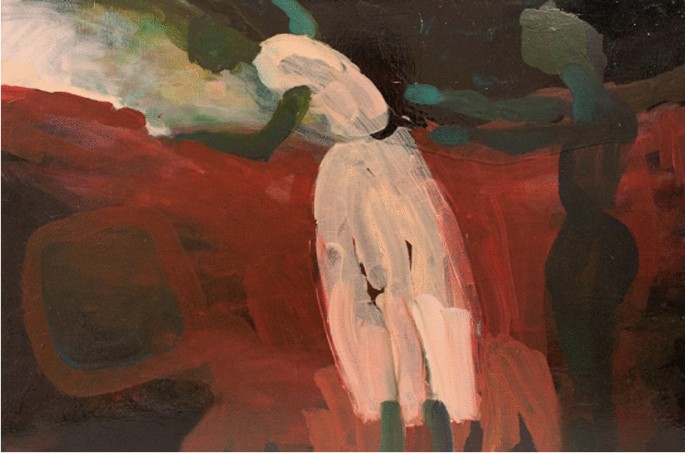

Helping people move through the creative process, suggests Basadur: ‘requires the leader to know how to synchronise the thinking of others. It involves building skills in being a process leader — not simply a content expert’ (2004). Jane Strickland illustrated this when I showed her the painting represented as Fig. 4 that I had produced in response to our first interview. Jane reflected:

The white and the person in the dark is saying to me, the white is about leading and about going forward, and the dark there is about, we’re solid and we’re behind you, but it's the light that's going to shine and go forward …. that's about supporting the person to try and achieve, and the analogy there with what I did is that the school and all the people I was working with supported me in what I was doing, in my endeavours. So, my supervisor from my masters, everybody who was involved who has supported me …. I wasn't held back. Every opportunity was given to me to achieve.

Discussion

Conversations (analogous to water molecules in the sea of creativity) can cause ‘waves’ of creativity but facilitating these conversations within and across institutions is easier said than done, especially for larger higher education institutions. Alan Robinson and Sam Stern (1998) suggest that ‘real leverage lies in ensuring that every employee has a sufficient understanding of the organisation’s activities to be able to tap its resources and expertise. The more employees know about their organization, the greater the chances that they will be able to make connections and get the information they need for a creative act’ (1998). Higher education institutions also need to ‘[t]ap into global expertise networks [and] .... build ad hoc constituencies of those sharing goals’, suggests Lombardo and Roddy (2011), and Jill Perry-Smith (2006) recommends that higher education institutions ‘blend’ academics, use ‘minisabbaticals’, as well as ‘bringing in visitors to fill complementary roles ...’ (2006). If there is a cultural element to developing creativity, as Maryam Piran et al. (2011) suggest is the case, higher education institutions might develop visions of what types of conversations would be most helpful. ‘Building connections, especially across boundaries’ (Jackson, 2003) and initiating well informed and open conversations can even be considered the foundations for higher education creativity. The leadership required for this should be authentic and process focused, where leaders ‘foster an autonomous work environment, thereby increasing subordinates’ psychological empowerment’ (Sun et al., 2011). This is something that Amabile et al. (2004) point out too:

Several behaviours deserve particular emphasis in the leader’s repertoire, behaviours requiring the following: skill in communication and other aspects of interpersonal interaction; an ability to obtain useful ongoing information about the progress of projects; an openness to and appreciation of subordinates’ ideas; empathy for subordinates’ feelings (including their need for recognition); and facility for using interpersonal networks to both give and receive information relevant to the project (2004).

Paul Schepers and Peter van den Berg (2007) include ‘adhocracy’ to the list of organisational factors associated with a perception of workplace creativity: They suggest that ‘individuals who perceive their organization as an adhocracy, and who experience high levels of participation and knowledge sharing, perceive their work environments as creative’(2007). Note that Schepers and van den Berg write of ‘perception’ of creative work environments, rather than the actual presence of a creative work environment, which was something that a Amabile et al. (1996) noted also.

The facilitation of well-informed and open conversations of this nature is not necessarily easy and Stuart Truman offers some sage advice: ‘It takes some doing’, he said, and one of the barriers that Stuart identified is that:

We don’t have nearly as much room as I think would be good for us to stop and reflect, stop and think very carefully and make time to talk with people, particularly in other disciplines in ways that could be very mutually beneficial.

Referring to creativity in higher education specifically: ‘we’ve got to find other ways of doing it’, said Stuart. He was a good storyteller and, without prompting, told me about an earlier era of academia that supported his point about having time to be creative:

That sort of creativity — um, won’t come nearly as naturally as it might have in an older style academic institution of that kind and so we’ve got to find other ways of doing it. If we’re going to achieve it yeah. …. Newman in his idea of university in his 19th Century treatise on what a university is about — talks about university being a place and he uses the term “Leisure” quite a lot. Now we might think lazy, so and so’s — that’s not what he means. He means having the time free of the normal pressure of making a living and getting through life that way, that you’ve got time to learn and reflect and do that cooperatively. It’s a social enterprise, not just an individual enterprise’ (second interview of Stuart Truman)

Jackson (2003) also identifies a lack of time as a barrier to creativity in higher education, along with other barriers such as staff and student attitudes, as well as structural, procedural and cultural factors. These structural and cultural factors, proposed Jackson (2003), can only be addressed by persuading leaders and decision-makers that is worth doing, a point that Stuart Truman also made: ‘Creativity in learning, teaching and research is being crowded out …. our academic masters need to have that very clearly before them’. This sort of thing is something that Richard Chatterfield also saw as a barrier to creativity in higher education, although not so much in terms of time constraints as constraints on autonomy:

I think that something that frustrates me sometimes with the way, say, the university operates is that sometimes it’s almost that there’s an assumption that individuals don’t have the nous or the creativity to really be given autonomy to make their own call on things. And instead there’s thousands of checks and balances put everywhere on the assumption that everyone’s going to underperform unless they’ve got to tick some box to prove that they’ve done x, y and z. And I prefer to go from the premise that people are professional, and you try and lay the fertile ground to allow them to teach well and research well. And give them the resources they need to do that and assume that they will do that and celebrate their achievements, rather than trying to find ways to manage people to death, if you know what I mean.

I think that where Richard bemoans the ‘checks and balances’ and a tendency to ‘manage people to death’, he is referring to a lack of empowerment, which takes us back to Schepers and van den Berg’s earlier comments about adhocracy (2007). Empowerment is something that has been identified as having a positive impact on creativity (Çekmecelioğlu & Günsel, 2011) so I asked Richard: Do you think most people respond in that sort of situation? He responded:

I think they do, actually. I think that even — I even found that people who I’d been led to believe were poor performers or unmotivated people or whatever seem to respond well to having a manager who was actually encouraging them and expectinged them to actually initiate new projects and do things they haven’t done perhaps for a while. And all — it seemed to me that all it took was for them to be encouraged and supported.

Richard’s ‘checks and balances’ and reference to tight managerial control could also be construed as a basis for the tensions that are a critical part of creativity in higher education. ‘Creative and habitual actions represent competing behavioural options’(Ford, 1996), and of course ‘individuals will prefer and/or resort to habitual actions, regardless of the conditions present related to creativity’ (Ford, 1996). On the other hand, the IBM study of creative leaders suggested that: ‘leaders who embrace the dynamic tension between creative disruption and operational efficiency can create new models of extraordinary value (Lombardo & Roddy, 2011). This sort of tension is continuous, so that the organisation is always becoming and evolving. It is where today’s creative thinkers question yesterday’s mental models, and their mental models will be questioned by future creative thinkers (Lozano, 2011) — where today’s ways, which came from questioning yesterday’s ways, become the tension for tomorrow’s creative action.

Conclusion

This discussion locates much of the current thinking about creativity in higher education institutions in a model with interrelated components that are easily articulated and would likely be well accepted by those who participate in higher education. Further, what is being proposed is not resource-dependent, contingent on, for example, international student enrolment numbers or even face-to-face gatherings, as COVID has taught us. The approach proposed here is also a starting point in pulling creativity back from the neoliberal narrative of financialisation that prioritise, for example, workplace readiness of graduating students (Gormley, 2020). The challenge for higher education institutions wanting to pursue creativity as a strategic goal is to refocus some of these ‘unplugged’ facets of higher education life, and ramp up the strategies, say, around open communication, that many higher education institutions will already have in place. The approach taken here envisages the higher education institution as a ‘sea of creativity’, to be sustained and benefited from, rather than being places of isolated creative events by clever individuals or teams. Such a conceptualisation places pressure on all higher education participants to engage in this ‘sea’ and to contemplate their own response to the subject of creativity.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 123–167.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184.

Amabile, T. M., & Mueller, J. S. (2008). Studying creativity, its processes, and its antecedents. In J. Zhou & C. Shalley (Eds.), Handbook of organizational creativity: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., & Kramer, S. J. (2004). Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 5–32.

Rae, J. (2018). Exploring creativity from within: An arts-based investigation. Art/research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, 3(2), 216–235.

Basadur, M. (2004). Leading others to think innovatively together: Creative leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 103–121.

Bourguignon, A. (2006). Preface: Creativity in organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 36(1), 3–7.

Boxenbaum, E., & Rouleau, L. (2011). New knowledge products as bricolage: Metaphors and scripts in organizational theory. The Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 272–296.

BrattstrÖm, A., LÖfsten, H., & Richtnér, A. (2012). Creativity, trust and systematic processes in product development. Research Policy, 41(4), 743–755.

Carter, P. (2007). Interest: The ethics of invention. In E. Barrett & B. Bolt (Eds.), Practice as research: Approaches to creative arts enquiry (pp. 15–25). I.B. Tauris.

Çekmecelioğlu, H. G., & Günsel, A. (2011). Promoting creativity among employees of mature industries: The effects of autonomy and role stress on creative behaviors and job performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 889–895.

Chakrabarty, S., & Woodman, R. (2009). Relationship creativity in collectives at multiple levels. In T. Rickards, M. A. Runco, & S. Moger (Eds.), The Routledge companion of creativity (pp. 189–205). Routledge.

Cook, M. J., & Leathard, H. L. (2004). Learning for clinical leadership. Journal of Nursing Management, 12(6), 436–444.

Cowan, J. (2006). How should I assess creativity? In N. Jackson, M. Oliver, M. Shaw, & J. Wisdon (Eds.), Developing creativity in higher education : An imaginative curriculum (pp. 156–172). Routledge.

DiLiello, T. C., & Houghton, J. D. (2006). Maximizing organizational leadership capacity for the future: Toward a model of self-leadership, innovation and creativity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(4), 319–337.

Egan, A., Maguire, R., Christophers, L., & Rooney, B. (2017). Developing creativity in higher education for 21st century learners: A protocol for a scoping review. International Journal of Educational Research, 82, 21–27.

European University Association (2007). Creativity in higher education: Report on the EUA creativity project 2006–2007. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/creativity%20in%20higher%20education%20-%20report%20on%20the%20eua%20creativity%20project%202006-2007.pdf

Ford, C. M. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1112–1142.

Gilmartin, M. J. (1999). Creativity: The fuel of innovation. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 23(2), 1.

Glaveanu, V. P. (2011). How are we creative together? Comparing sociocognitive and sociocultural answers. Theory & Psychology, 21(4), 473–492.

Grbich, C. (2012). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Gormley, K. (2020). Neoliberalism and the discursive construction of ‘creativity.’ Critical Studies in Education, 61(3), 313–328.

Govan, E., & Munt, D. (2003). The crisis of creativity: Liminality and the creative grown-up. Retrieved from http://www.rhul.ac.uk/drama/creativityandhealth/paper%20-%20Crisis%20of%20creativity.pdf

Grieve, A. (2009). Social networks and creativity. In T. Rickards, M. A. Runco, & S. Moger (Eds.), The Routledge companion of creativity (pp. 132–145). Routledge.

Hargadon, A., & Sutton, R. I. (1997). Technology brokering and innovation in a product development firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 716–749.

Hargadon, A. B., & Bechky, B. A. (2006). When collections of creatives become creative collectives: A field study of problem solving at work. Organization Science, 17(4), 484–500.

Jackson, N. (2003). Creativity in higher education. Higher Education Academy, York, UK. Available at: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources.asp.

Jackson, N., & Sinclair, C. (2006). Developing students' creativity: Searching for an appropriate pedagogy. In N. Jackson, M. Oliver, M. Shaw & J. Wisdon (Eds.), Developing creativity in higher education : an imaginative curriculum (pp. xx, 236 p.). Routledge.

Jahnke, I., & Liebscher, J. (2020). Three types of integrated course designs for using mobile technologies to support creativity in higher education. Computers & Education, 146, 103782.

Juceviciene, P., & Ceseviciute, I. (2009). Organizational creativity as a factor of the emergence of learning organization. Social Sciences, 65(3), 40–48.

Kasperson, J. K. (1978). Psychology of the scientist: XXXVII. Scientific creativity: A relationship with information channels. Psychological Reports, 42(3), 691–694.

Lombardo, B., & Roddy, D. (2011). Cultivating organizational creativity in an age of complexity. IBM Institute for Business Value.

Lozano, R. (2011). Creativity and organizational learning as means to foster sustainability. Sustainable Development, 22(3), 205–216.

Mack, J. (2011). The sea: A cultural history. Reaktion Books.

Manathunga, C., Selkrig, M., Sadler, K., & Keamy, K. (2017). Rendering the paradoxes and pleasures of academic life: Using images, poetry and drama to speak back to the measured university. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(3), 526–540.

Mannay, D. (2010). Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research, 10(1), 91–111.

Mercier, M., Vinchon, F., Pichot, N., Bonetto, E., Bonnardel, N., Girandola, F., & Lubart, T. (2021). COVID-19: A boon or a bane for creativity? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3916.

Metcalfe, A. S., & Blanco, G. L. (2019). Visual research methods for the study of higher education organizations. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 153–202). Springer.

Miller, A. I. (1996). Metaphors in creative scientific thought. Creativity Research Journal, 9(2), 113–130.

Monge, P. R., Cozzens, M. D., & Contractor, N. S. (1992). Communication and motivational predictors of the dynamics of organizational innovation. Organization Science, 3(2), 250–274.

Moran, S. (2009). Metaphor foundations in creativity research: Boundary vs. organism. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 43(1), 1–22.

Mumford, M. D., Scott, G. M., Gaddis, B., & Strange, J. M. (2002). Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 13(6), 705.

Munt, D., & Hargreaves, J. (2009). Aesthetic, emotion and empathetic Imagination: Beyond innovation to creativity in the health and social care workforce. Health Care Analysis, 17(4), 285–295.

Perry-Smith, J. E. (2006). Social yet creative: The role of social relationships in facilitating individual creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 85–101.

Piran, M., Jahani, J., & Al-sadat Nasabi, N. (2011). Relationship between organizational culture and personal creativity from the viewpoint of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences’ academic staff (faculty members), 2010. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(7), 1181–1189.

Rego, A., Sousa, F., & Marques, C. (2011). Authentic leadership promoting employees' psychological capital and creativity. Journal of Business Research, 65(3), 429–437.

Robinson, A. G., & Stern, S. (1998). Corporate creativity: How innovation and improvement actually happen. Berrett-Koehler Pub.

Russ, S. W., & Fiorelli, J. A. (2010). Developmental Approaches to Creativity. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity (pp. 233). Cambridge University Press.

Schepers, P., & van den Berg, P. T. (2007). Social factors of work-environment creativity. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(3), 407–428.

Serres, M. (1982). The Parasite, trans. Lawrence R. Schehr. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Shalley, C. E., & Gilson, L. L. (2004). What leaders need to know: A review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 33–53.

Somerville, M. (2007). Postmodern emergence. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (QSE), 20(2), 225–243.

Sternberg, R. J., & Vroom, V. (2002). The person versus the situation in leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 301.

Sun, L. Y., Zhang, Z., Qi, J., & Chen, Z. X. (2011). Empowerment and creativity: A cross-level investigation. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 55–65.

Tanggaard, L. (2018). Creativity in higher education: Apprenticeship as a “Thinking Model” for bringing back more dynamic teaching and research in a university context. In Sustainable Futures for Higher Education (pp. 263–277). Springer.

Tosey, P. (2006). Interfering with the interferance: An emergent perspective on creativity in higher education. In Jackson.N, Oliver.M, Shaw.M & SWWisdon.J (Eds.), Developing creativity in higher education : an imaginative curriculum (pp. 29–42). Routledge.

Van de Ven, A. H. (1986). Central problems in the management of innovation. Management science, 32(5), 590–607.

Weick, K. (1979). The social psychology of organizing: Topics in social psychology series. McGraw-Hill.

Wisdom, J. (2006). Developing higher education teachers to teach creatively. In Jackson.N, Oliver.M, Shaw.M & SWWisdon.J (Eds.), Developing creativity in higher education : an imaginative curriculum (pp. 183–196). Routledge.

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Towards atheory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18(2), 293.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

No funds, grants, or other support was received. The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

The methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of the Charles Sturt University (Ethics approval number: 2010/099).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rae, J. Connecting for Creativity in Higher Education. Innov High Educ 48, 127–143 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-022-09609-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-022-09609-6