Abstract

Using carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis, we characterised food web properties of the deep subtropical Fei-Tsui Reservoir (FTR), which was recently altered from a lotic to a lentic system after dam construction. In the littoral zone, zoobenthos showed strong reliance (83.9%) on benthic algal production. Zoobenthos were never found in the profundal zone because of anoxia. Zooplankton depleted 13C more than that of particulate organic matter as their putative food source, suggesting a contribution of methane-derived carbon to pelagic food webs. Excluding juveniles, non-native and fluvial species, adult fish showed strong reliance (on average 80.9%) on benthic production, weakly coupled with pelagic food webs. These results contrast low benthic production reliance (on average 27.4%) for a fish community in Lake Biwa, which is also classified as a subtropical lake. Both lakes are characterised by deep pelagic waters but quite different in their geological ages, suggesting that the aquatic communities in the FTR have fluvial origins, and their lacustrine history was too short for them to adapt to newly emerged deep pelagic habitat. Our isotope data are useful as a reference of newly established lentic food webs to monitor ongoing ecological and evolutionary dynamics as a result of anthropogenic disturbances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dams and reservoirs have been constructed to meet accelerated demands for water and energy resources as populations experience explosive growth and climate change worldwide (Nilsson et al., 2005). While dams provide high public utility, they can negatively impact river ecosystems by drastically changing waterway from lotic to lentic systems (McAllister et al., 2001). In dammed rivers, some taxa can modify and adapt their life histories to sustain their populations; however, others that cannot adapt may go into local extinction due to loss of original habitats. At present, dam construction is considered as one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss in the freshwater ecosystems through the alteration and homogenisation of natural hydrological regimes (Poff et al., 2007), the creation of physical barriers to migratory species (Liermann et al., 2012), the dispersal and colonisation of non-native lentic species (Havel et al., 2005), and the pollution and eutrophication at dam sites (Dudgeon, 2000). Therefore, it is important to perform ecosystem assessments after dam construction for water quality management and biodiversity conservation.

Stable isotope analysis (SIA) is a powerful tool to assess ecosystems, especially food web properties characterised by trophic interactions within a biological community. Food web characterisation is of ecological and social significance because trophic interactions can drive nutrient cycling and energy flows, which in turn affect ecosystem services (e.g. water quality, food supply for humanity). At present, the stable isotopic approach is the preferred method for studying aquatic food webs, in which carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope ratios, for aquatic species, are used to distinguish primary trophic pathways, for example, pelagic versus littoral pathways (France, 1995a, b) or aquatic versus terrestrial pathways (Peterson & Fry, 1987; Finlay, 2001). Especially for fish, their isotopic signatures provide useful information in estimating the relative importance of trophic energy flows in lake ecosystems. Fish predators integrate a variety of trophic pathways as they couple pelagic and littoral food webs due to their high mobility and omnivory (Vander Zanden & Vadeboncoeur, 2002; Vander Zanden et al., 2011). The stable isotopic approach can also be applied to assess food web alterations in aquatic ecosystems under human disturbances (Vander Zanden et al., 1999; Layman et al., 2007; Anderson & Cabana, 2009; Hamaoka et al., 2010). In most cases, however, stable isotopic studies are conducted after ecosystem alterations were perceived. As such, limited information is available on original conditions before the disturbance (but see Okuda et al., 2012; Vander Zanden et al., 2003).

Newly constructed dams and reservoirs provide a good possibility to understand ecological processes of food web alterations if initial conditions of the lentic system are assessed soon after dam or reservoir construction. In this study, we conducted δ13C and δ15N analysis to characterise food web properties of the Fei-Tsui Reservoir (hereafter, FTR; Fig. 1; Table 1), which was established in 1987 to supply drinking water for more than 5 million people in metropolitan Taipei. Since its construction, the local government has been responsible for ecosystem management of the reservoir, focusing mainly on water quality. In contrast to physical and chemical characteristics, biological information was monitored less with the exception of phytoplankton data that were monitored as an indicator of water quality (Wu et al., 2007). Recently, Chang et al. (2014a, b) reported community dynamics and size-based food webs in the FTR, focusing on plankton communities in pelagic waters. A holistic approach that encompasses benthos and fish as higher consumers in coastal and pelagic waters is needed to view the overall trophic energy flows in lentic food webs of the FTR before future anthropogenic disturbances occur. This study can, therefore, be regarded as a reference for ongoing ecosystem monitoring.

In this study, we also intend to compare food web properties of FTR with those of Lake Biwa, in which a holistic approach towards food web analysis was performed in a similar way to the present study (Okuda et al., 2012). According to Yoshimura (1937)’s lake classification, both lakes were classified as subtropical, monomictic lakes in Monsoon Asia. During the quaternary glaciation, terrestrial and aquatic species migrated between southern Japan and Taiwan through a land bridge, often forming sister species (Chiang & Schaal, 2006; Ho et al., 2016). Such a biogeographical history has enabled the same species and congeners to exist in both lakes. These lakes are also similar in terms of depth and trophic state (Table 1). Considering their biogeographical and limnological backgrounds, they are comparable in relation to trophic positions of some common taxa. However, they are quite different temporally as the lentic waters emerged at different times. We will discuss how the historical difference in the lentic community colonisation affects trophic energy flows in these deep lakes.

Materials and methods

Study site and environmental issues

FTR, one of the largest reservoirs in Taiwan, is located downstream of Peishih Creek, residing in a watershed of 303 km2 in northern Taiwan (121°34′E, 24°54′N; Fig. 1a). Its limnological and bathymetric characteristics are shown in Table 1. Although the FTR was classified as an oligotrophic lake for several years after dam construction (Chang & Wen, 1997), its trophic state currently ranges between mesotrophic and eutrophic according to Carlson’s trophic state index (Chou et al., 2007). Dominance in phytoplankton flora has shifted from dinoflagellates to cyanobacteria and green algae, suggesting a long-term trend towards eutrophication (Wu & Chou, 1998; Wu et al., 2007).

In the reservoir, seasonal and vertical profiles of dissolved oxygen are affected by weather- and climate-driven hydrodynamics (Fan & Kao, 2008). A recent concern is the frequent release of typhoon-induced suspension interflows from the main tributary, increasing phosphorous loading and affecting water quality (Chen et al., 2006). Moreover, strong summer stratification and incomplete winter mixing due to warming have often caused hypoxia in profundal waters (Itoh et al., 2015), which may have non-linear and lethal effects on profundal communities. Considering such emerging environmental issues, long-term ecosystem monitoring was launched in 2004. The physical and chemical environmental data we obtained have been published (Itoh et al., 2015; Chow et al., 2016).

Field sampling

Prior to food web analysis, we conducted field sampling of fish, zooplankton, zoobenthos, and their basal food sources. We collected zooplankton and their putative food sources from pelagic waters at the monitoring station near the dam (113.5 m at depth; Fig. 1b). On 17 November 2009, meso- and macro-zooplankton were collected with a 100-μm-mesh plankton net towed vertically in the epilimnion (0–18 m at depth). For sampling of particulate organic matter (POM) as basal food for pelagic consumers, lake waters were collected at the depth of 2 m with a 5-L Go-Flo bottle (General Oceanics, Miami, FL) on 13 and 27 October and 10 November 2009. Water samples were screened with a 10-μm-mesh and then filtrated with glass fibre filter (GF/F, 0.7 μm, Whatman) pre-combusted at 450°C for 2 h. Particle sizes of 0.7–10 μm cover the size range of meso- and macro-zooplankton prey in the FTR (Chang et al., 2014b). These time-series POM samples were mixed in equal quantities to integrate temporal variations in their isotopic signatures, reflecting a high turnover rate for small-sized plankton. This procedure is reasonable because large-sized zooplankton biomass integrates temporal variation in their dietary isotopic signatures for a few months (Ho et al., 2016). In FTR, seasonal pattern of surface POM isotopic signatures is predictable (See Fig S1 in Ho et al., 2016), so that our mixing model with pooled POM data is robust to temporal variation in its isotopic signatures.

While monitoring the station near the dam, we collected surface sediment from the deep lake bottom as the putative food source for profundal consumers, using an Ekman-Berge grab sampler. The sediment samples were sorted for zoobenthos, but no individuals were found in profundal habitats.

We also collected zoobenthos and fish juveniles at a littoral site (Fig. 1b) using a Sarvar net. As a basal food source for littoral consumers, we collected epilithic organic matter (EOM) from the littoral habitat, scraping it off from each of four boulders with a brush. After removing zoobenthos from these suspended samples with a 150-μm-mesh net, they were mixed and filtered through pre-combusted GF/F filters. Leaf litter was also collected as allochthonous terrigenous organic matter (TOM).

Adult fish specimens were obtained from an aboriginal tribe, with government-authorised licenses to catch the fish in the FTR, during our sampling period. Except for the aboriginal fishing, fish sampling using fishing gears and boat in the FTR is strictly prohibited by Taipei Feitsui Reservoir Administration even if it is the academic purpose. Such an administrative constraint restricted our sampling design to small sample size and narrow sampling area.

These samples were chilled and transferred to the laboratory. Dominant zooplankton species were sorted and identified under a microscope. Due to their little mass, small-sized animal samples were prepared in bulk for SIA. For adult fish specimens, we measured their total length or standard length in millimetres and then excised their muscle tissues from the dorsal part of the lateral body. For zoobenthos and juvenile fish samples, their entire mass was prepared for SIA. All samples were dried at 60°C for 24 h.

Stable isotope analysis

Dry samples were ground into fine powder. For animals, the ground samples were immersed in chloroform:methanol (2:1) solution for 24 h to remove lipids according to Kling et al. (1992). Each sample was weighed and wrapped in a tin capsule for combustion. We determined carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios for each sample using a mass spectrometer (CF/IRMS; Conflo II and Delta S, Finnigan MAT, Germany), and carbon and nitrogen contents were measured using elemental analyzers (EA1108, Fisons, Italy). Ratios (R) of the heavy isotope to the light isotope (13C/12C, 15N/14N) were expressed in parts per thousand, relative to the standards in delta notation following the formula:

Vienna Pee Dee belemnite and atmospheric nitrogen were used as standards for carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope ratios, respectively. The analytical precision based on working standard was ±0.1‰ for δ13C and δ15N.

Estimation of trophic position

We estimated trophic position of consumers in the lentic food web of the FTR based on the following stable isotope mixing model (see also Okuda et al., 2012).

where f 1 and f 2 represent the proportion of reliance of the two major primary producers in the lentic food web, that is, phytoplankton (POM) and benthic microalgae (EOM), respectively. δR 1, δR 2, and δR cons (R = 13C or 15N) are stable isotope ratios of phytoplankton, benthic microalgae, and each focal consumer, respectively. TP is trophic position. Δδ13C ef and Δδ15N ef are trophic enrichment factors, assuming that consumer’s δ15N is enriched by 3.4‰ relative to its diets (Minagawa & Wada, 1984) and its δ13C by 0.8‰ (DeNiro & Epstein, 1978). The above mixing model enables us to estimate TP and production reliance (i.e. f n ) for each consumer. If consumer’s production reliance on either of the two basal foods slightly exceeds one, we regarded it as exclusive reliance (i.e. 100%). In the case in which fluvial fish migrate between coastal and stream habitats (see Results), we also used the EOM and TOM as basal food sources in the isotope mixing model.

Results

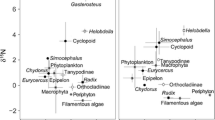

We measured a total of 45 samples, including 10 fish, 2 macrozoobenthos and 4 zooplankton taxa, together with their basal food resources from littoral and pelagic waters in the FTR (Table 2). One littoral zoobenthos taxon (Chironomidae) was excluded from our isotopic data because its carbon and nitrogen contents were less than the lower detection limit. Its lentic food web was delineated on δ13C-δ15N bi-plot space (Fig. 2).

Trophic positions of each taxon in the lentic food web of Fei-Tsui Reservoir. Thick arrows represent the hypothetical trophic pathways starting from phytoplankton and benthic microalgae using assumptions from our mixing model. Each plot and bar are averaged and presented with the standard deviation of isotopic signatures for each taxon. Plot numbers correspond to taxon codes in Table 2

In pelagic habitats, trophic position cannot be estimated for meso- and macro-zooplankton because they depleted 13C substantially more than POM, which is their putative food source (Fig. 2; Table 2). Amongst the zooplankton samples, two copepods and the bulk zooplankton community, which was also dominated by copepods, enriched 15N by 3.5‰, on average, more than two cladocerans. This suggests that the former TLs were higher than the latter by around one although their absolute values could not be calculated because of large deviations from the isotopic range of their putative food sources, POM and EOM. In littoral habitats, by contrast, shrimp enriched their 13C, showing strong reliance on EOM (83.9%; Table 2).

Fish occupied broad trophic niche spaces in the lentic food web of the FTR (Fig. 2; Table 1). A catfish Silurus asotus Linnaeus, 1758, a top predator, had the highest TP (3.84 TP), showing its strong reliance on benthic algal production (87.7%). Three fish species (i.e. juvenile Rhinogobius sp., Carassius cuvieri Temminck & Schlegel, 1846 and Oxyeleotris marmorata (Bleeker, 1852)) had relatively low δ13C. SIA of a landlocked goby, Rhinogobius sp., in Lake Biwa revealed that adult fish are benthic feeders in littoral habitats, while 0+ aged fish have a planktonic life stage before their settlement (Maruyama et al., 2001). Amongst juveniles of Rhinogobius sp. in the FTR, the highest reliance on phytoplankton production was 74.0% although adult fish showed strong reliance on benthic algal production (79.9%). C. cuvieri, a pelagic species endemic to Lake Biwa, was possibly introduced into the FTR after dam construction since it cannot sustain populations in lotic environment. O. marmorata is a fluvial benthic predator whose basal food may be derived from allochthonous terrigenous organic matter (TOM) in river habitats but not from pelagic POM since it migrates between littoral and river habitats. Assuming that this fish relies on allochthonous TOM (i.e. leaf litter) and autochthonous EOM, we estimated its production reliance on the TOM as 88.7% and its TP as 3.97. Excluding juveniles, non-native and fluvial species, adult native lacustrine fish showed on average 80.9% benthic production reliance.

Discussion

Pelagic and profundal food webs

In pelagic food webs of the FTR, TPs of zooplankton taxa could not be estimated appropriately because their isotopic signatures deviated from the isotopic range of putative food sources. Based on their low δ15N values relative to POM, one may infer that pelagic food webs are subsidised by allochthonous TOM with a low δ15N value as is often the case for small lakes (Pace et al., 2004; Cole et al., 2006, 2011). Cole et al. (2006) demonstrated that TOM is primarily passed to pelagic food webs as a part of POM. In the FTR, however, TOM contributes little to zooplankton production, rejecting the possibility of terrestrial subsidies (Ho et al., 2016).

Apart from their food sources, when focusing on the locations of copepods and cladocerans on the δ13C-δ15N bi-plot space, their relative trophic positions were markedly different between the two dominant taxa. Assuming that cladocerans are grazers and also that the trophic enrichment factor is 3.4‰ for δ15N, copepods are considered carnivores. Such trophic niche segregation has hitherto been reported for these two taxa in many lakes (Yamada et al., 1998; Grey et al., 2001; Matthews & Mazumder, 2003; Karlsson et al., 2004). Since copepods are raptorial feeders, it is likely that they feed on small-sized grazers, such as protozoa, rotifers, nauplii, and cladoceran larvae. For plankton communities, intra-guild predation (i.e. predation on small-sized zooplankton by large-sized zooplankton) is often prevalent in lakes dominated by microbial loops (Grey et al., 2001; Karlsson et al., 2004).

In the FTR, it is also interesting that the zooplankton community had a much lower carbon isotope ratio than POM as its putative food source. As pointed out by Jones & Grey (2011), such an isotopic mismatch between POM and zooplankton could be ascribed to zooplankton consumption of 13C-depleted phytoplankton, which assimilate 13C-depleted CO2 derived from bacterial respiration of terrigenous DOC in humic lakes. In the FTR, in contrast, bacterial decomposition of DOC is facilitated only when phosphorous is loaded from the catchment after strong typhoons (Tseng et al., 2010) and heterotrophically respired 13C-depleted CO2 is not so much reflected in the carbon isotope ratio of dissolved CO2 in surface waters (−12 to −17‰; Itoh et al. unpublished data), suggesting another carbon source for zooplankton. In eutrophic and/or humic lakes, dissolved methane generated from the anoxic lake bottom and characterised by an extremely low carbon isotope ratio is one of the major carbon sources for zooplankton (Bastviken et al., 2003; Taipale et al., 2008; Kankaala et al., 2010). This trophic pathway from dissolved methane to zooplankton is mediated by methane-oxidising bacteria (MOBs), defined as methanotrophic food webs. Long-term monitoring of methanotrophic food webs is of ecological importance in understanding how carbon cycling is altered in lakes affected by anthropogenic activities.

In the FTR, it has been reported that MOBs dominate profundal bacterial communities, showing remarkable vertical and seasonal variations in community compositions (Kojima et al., 2014; Kobayashi et al., 2016). Itoh et al. (2015) experimentally demonstrated that the methane oxidation activity is highest in deep sub-oxic layers, in which both dissolved methane and oxygen are available to MOBs. In the deep FTR, methanotrophic food webs can be mediated through zooplankton vertical migration to feed on profundal MOBs, leading to the coupling of pelagic and profundal food webs. Using isotopic and theoretical models, Ho et al. (2016) revealed that the relative contribution of MOBs to zooplankton production seasonally varied from 0.6 to 14.6% in the FTR, depending on hydrodynamic changes in dissolved methane and oxygen concentrations. In the FTR, methanotrophic contributions are not as great as the contributions in boreal lakes (up to 50%; Kankaala et al., 2010), which generate allochthonous carbon subsidies for pelagic food webs during less productive seasons. Using meta-analysis for lakes worldwide, Bastviken et al. (2004) predicted that methane production would increase with increasing total phosphorous and dissolved organic carbon concentrations. Considering the trend towards eutrophication after dam construction, it is reasonable to expect long-term changes in methanotrophic contributions to pelagic food webs in the FTR. As reported by Ho et al. (2016), the results from this study allow for long-term monitoring of plankton isotope signatures to assess alterations in trophic carbon flows in pelagic food webs due to climate and land use changes.

In deep lakes, the oxic–anoxic conditions of the lake bottom habitat also affect infaunal zoobenthos communities and their trophic carbon flows in profundal food webs. In Lake Biwa, many benthic species have adapted to profundal habitats since deepening of the lake basin ca. 0.4 million BC (Kawanabe et al., 2012). Some hypoxia-tolerant burrowing chironomids are characterised by extreme isotopic depletion of 13C, suggesting the existence of methanotrophic food webs in the sub-surface of lake sediments where an oxidation–reduction boundary layer has developed (Kiyashko et al., 2001). In the FTR, by contrast, there exist no zoobenthos in the profundal habitat that is anoxic. Since original zoobenthos faunas were living in shallow and lotic environments before the construction of this reservoir, they may not be tolerant to deep anoxic conditions. The long-term monitoring revealed that the profundal habitat interannually alternates between anoxic and hypoxic conditions, depending on the intensity of winter vertical mixing under changing climates (Itoh et al., 2015). If there are some scopes for hypoxia-tolerant species to colonise populations from adjacent lakes, trophic carbon flows in profundal food webs may be modified over time.

Trophic energy flows to higher consumers

In the FTR, a lacustrine fish community, except for juvenile, fluvial and non-native fish, showed 80.9% of benthic production reliance. It contrasts with Lake Biwa in which the benthic production reliance is 27.4% for the whole fish community (Okuda et al., 2012). The food chain length, defined as the TP of top predators, was not so different between the FTR (3.84 TP for a catfish Silurus asotus) and Lake Biwa (3.75 TP for a giant catfish Silurus biwaensis Tomoda, 1961; Okuda et al., 2012), whereas their benthic production reliance was much higher for the former (87.7%) than for the latter (25.6%). Vander Zanden et al. (2011) estimated benthic production reliance as on average 57% for fish communities in 75 lakes worldwide, in which carbon isotope data are available for food web analysis. The relative contributions of benthic algae to whole-lake primary production can be affected by bathymetry (Vadeboncoeur et al., 2008). Amongst temperate lakes of North America, for instance, a lake trout, a top predator, shifts its production reliance from benthic to pelagic drastically when the lake’s surface area is more than 10 km2 (Vander Zanden & Vadeboncoeur, 2002). Large lakes tend to have a lower perimeter-to-area ratio, and they also tend to be deeper than small lakes, thus reducing the relative contribution of benthic algae to the whole-lake production and subsequently to trophic carbon flows in zoobenthos and fish (Vadeboncoeur et al., 2002). Considering the limited area of shallow coastal habitats in dams and reservoirs with steep slopes, it is likely that benthic algae contribute little to the whole-lake primary production in the FTR.

In this study, because the sample size and sampling area were limited under the administrative constraints, our results may be less conclusive in relation to intraspecific and spatial variations in the fish trophic position and production reliance within the reservoir. Considering a general rule that large body-sized fish have high mobility and low turnover rate (McCann et al., 2005), however, our adult fish specimens should have time- and space-integrated isotopic information on food webs, ensuring that our estimation of their trophic position and production reliance is reliable. Since commercial and recreational fishing, except for small-scale aboriginal fishing, is prohibited by the Administration of Taipei FTR, the possibility of overexploitation of pelagic fish, which would bias fish community compositions to littoral species relying on benthic production, can be ruled out. Rather, strong benthic production reliance can be ascribed to the fact that the native fish have fluvial origins, associated with habits for feeding on benthos in river habitats before the reservoir was constructed.

In the FTR, interestingly, a non-native fish introduced from Lake Biwa showed the highest reliance (81.9%) on pelagic production. In Lake Biwa, many endemic fish species evolved from their fluvial ancestors to adapt to the pelagic environment after the lake deepened through faulting ca. 0.4 million years ago (Okuda et al., 2013). In the FTR, by contrast, its lentic history may be too short for the native fish to adapt well to the pelagic habitat. However, evolutionary biologists have recently reported numerous cases studying rapid evolution, which occurs on an ecological time scale much shorter than expected from conventional evolutionary process (Stockwell et al., 2003; Hairston Jr. et al., 2005). For instance, the bluegill sunfish Lepomis macrochirus Rafinesque, 1810 was introduced into Lake Biwa from the United States in the 1960s. Its colonised populations showed benthic morphs feeding on littoral zoobenthos during the early phases of colonisation in the 1970s (Terashima, 1980). More than half a century after the introduction, however, some of the bluegill sunfish shifted to pelagic morphs with specialised feeding habits for plankton preys (Yonekura et al., 2002). Such trophic polymorphism was also detected by SIA (Uchii et al., 2007). For native fish species in the FTR, on one hand, it is interesting to correlate long-term changes in their isotopic signatures with the shift from benthic to pelagic habitats over time from now on. As in the case of the FTR, on the other hand, we have to warn against human introduction of non-native pelagic fish in term of biodiversity conservation because they easily occupy vacant niches after reservoir construction (Liew et al., 2016), decreasing opportunities for ecological adaptations of the native fish to the pelagic habitat.

At present, the trophic state of FTR has become mesotrophic and sometimes even eutrophic, a gross difference from its original state as oligotrophy immediately after reservoir construction. The dams and reservoirs are destined to become eutrophic, sooner or later, given nutrient loading from the catchment. The relative importance of whole-lake primary production will shift from benthic algal to phytoplankton production through eutrophication (Vadeboncoeur et al., 2001). Such a change in primary production can also alter trophic carbon flows to aquatic consumers, which can be detected by carbon isotope analysis (Vadeboncoeur et al., 2003). Our study is currently descriptive, but it can be a milestone for future ecosystem assessments and evolutionary research for the FTR. As reported for Lake Biwa (Okuda et al., 2012), long-term isotopic monitoring in the FTR will provide more insights into the dynamic nature of lentic food webs due to ongoing anthropogenic activities.

References

Anderson, C. & G. Cabana, 2009. Anthropogenic alterations of lotic food web structure: evidence from the use of nitrogen isotopes. Oikos 118: 1929–1939.

Bastviken, D., J. Cole, M. Pace & L. Tranvik, 2004. Methane emissions from lakes: Dependence of lake characteristics, two regional assessments, and a global estimate. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 18: GB4009.

Bastviken, D., J. Ejlertsson, I. Sundh & L. Tranvik, 2003. Methane as a source of carbon and energy for lake pelagic food webs. Ecology 84: 969–981.

Chang, C. W., T. Miki, F. K. Shiah, S. J. Kao, J. T. Wu, A. R. Sastri & C. H. Hsieh, 2014a. Linking secondary structure of individual size distribution with nonlinear size-trophic level relationship in food webs. Ecology 95: 897–909.

Chang, C. W., F. K. Shiah, J. T. Wu, T. Miki & C. H. Hsieh, 2014b. The role of food availability and phytoplankton community dynamics in the seasonal succession of zooplankton community in a subtropical reservoir. Limnologica 46: 131–138.

Chang, S. P. & C. G. Wen, 1997. Changes in water quality in the newly impounded subtropical FeiTsui Reservoir, Taiwan. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 33: 343–357.

Chen, Y.-J. C., S.-C. Wu, B.-S. Lee & C.-C. Hung, 2006. Behavior of storm-induced suspension interflow in subtropical Feitsui Reservoir, Taiwan. Limnology and Oceanography 51: 1125–1133.

Chiang, T. Y. & B. A. Schaal, 2006. Phylogeography of plants in Taiwan and the Ryukyu archipelago. Taxon 55: 31–41.

Chou, W. S., T. C. Lee, J. Y. Lin & S. L. Yu, 2007. Phosphorus load reduction goals for feitsui reservoir watershed, Taiwan. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 131: 395–408.

Chow, M. F., F. K. Shiah, C. C. Lai, H. Y. Kuo, K. W. Wang, C. H. Lin, T. Y. Chen, Y. Kobayashi & C. Y. Ko, 2016. Evaluation of surface water quality using multivariate statistical techniques: a case study of Fei-Tsui Reservoir basin, Taiwan. Environmental Earth Sciences 75: 6.

Cole, J. J., S. R. Carpenter, M. L. Pace, M. C. Van de Bogert, J. L. Kitchell & J. R. Hodgson, 2006. Differential support of lake food webs by three types of terrestrial organic carbon. Ecology Letters 9: 558–568.

Cole, J. J., S. R. Carpenter, J. Kitchell, M. L. Pace, C. T. Solomon & B. Weidel, 2011. Strong evidence for terrestrial support of zooplankton in small lakes based on stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 108: 1975–1980.

DeNiro, M. J. & S. Epstein, 1978. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 42: 495–506.

Dudgeon, D., 2000. Large-scale hydrological changes in tropical Asia: Prospects for riverine biodiversity. BioScience 50: 793–806.

Fan, C. W. & S. J. Kao, 2008. Effects of climate events driven hydrodynamics on dissolved oxygen in a subtropical deep reservoir in Taiwan. Science of the Total Environment 393: 326–332.

Finlay, J. C., 2001. Stable-carbon-isotope ratios of river biota: implications for energy flow in lotic food webs. Ecology 82: 1052–1064.

France, R. L., 1995a. Carbon-13 enrichment in benthic compared to planktonic algae: foodweb implications. Marine Ecology Progress Series 124: 307–312.

France, R. L., 1995b. Differentiation between littoral and pelagic food webs in lakes using stable carbon isotopes. Limnology and Oceanography 40: 1310–1313.

Grey, J., R. I. Jones & D. Sleep, 2001. Seasonal changes in the importance of the source of organic matter to the diet of zooplankton in Loch Ness, as indicated by stable isotope analysis. Limnology and Oceanography 46: 505–513.

Hairston Jr., N. G., S. P. Ellner, M. A. Geber, T. Yoshida & J. A. Fox, 2005. Rapid evolution and the convergence of ecological and evolutionary time. Ecology Letters 8: 1114–1127.

Hamaoka, H., N. Okuda, T. Fukumoto, H. Miyasaka & K. Omori, 2010. Seasonal dynamics of a coastal food web: Stable isotope analysis of a higher consumer. In Ohkouch, N., I. Tayasu & K. Koba (eds), Earth, Life, and Isotopes. Kyoto University Press, Kyoto: 161–181.

Havel, J. E., C. E. Lee & M. J. Vander Zanden, 2005. Do reservoirs facilitate invasions into landscapes? BioScience 55: 518–525.

Ho, P.-C., N. Okuda, T. Miki, M. Itoh, F.-K. Shiah, C.-W. Chang, S. S.-Y. Hsiao, S.-J. Kao, M. Fujibayashi & C.-H. Hsieh, 2016. Summer profundal hypoxia determines the coupling of methanotrophic production and the pelagic food web in a subtropical reservoir. Freshwater Biology 61: 1694–1704.

Itoh, M., Y. Kobayashi, T. Y. Chen, T. Tokida, M. Fukui, H. Kojima, T. Miki, I. Tayasu, F. K. Shiah & N. Okuda, 2015. Effect of interannual variation in winter vertical mixing on CH4 dynamics in a subtropical reservoir. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 120: 1246–1261.

Jones, R. I. & J. Grey, 2011. Biogenic methane in freshwater food webs. Freshwater Biology 56: 213–229.

Kankaala, P., S. Taipale, L. Li & R. I. Jones, 2010. Diets of crustacean zooplankton, inferred from stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses, in lakes with varying allochthonous dissolved organic carbon content. Aquatic Ecology 44: 781–795.

Karlsson, J., A. Jonsson, M. Meili & M. Jansson, 2004. δ15N of zooplankton species in subarctic lakes in northern Sweden: effects of diet and trophic fractionation. Freshwater Biology 49: 526–534.

Kawanabe, H., M. Nishino & M. Maehata (eds), 2012. Lake Biwa: Interactions Between Nature and People. Springer, Dordrecht.

Kiyashko, S. I., T. Narita & E. Wada, 2001. Contribution of methanotrophs to freshwater macroinvertebrates: evidence from stable isotope ratios. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 24: 203–207.

Kling, G. W., B. Fry & W. J. O’Brien, 1992. Stable isotopes and planktonic trophic structure in arctic lakes. Ecology 73: 561–566.

Kobayashi, Y., H. Kojima, M. Itoh, N. Okuda, M. Fukui & F. K. Shiah, 2016. Abundance of planktonic methane-oxidizing bacteria in a subtropical reservoir. Plankton & Benthos Research 11: 144–146.

Kojima, H., R. Tokizawa, K. Kogure, Y. Kobayashi, M. Itoh, F. K. Shiah, N. Okuda & M. Fukui, 2014. Community structure of planktonic methane-oxidizing bacteria in a subtropical reservoir characterized by dominance of phylotype closely related to nitrite reducer. Scientific Reports 4: 5728.

Layman, C. A., J. P. Quattrochi, C. M. Peyer & J. E. Allgeier, 2007. Niche width collapse in a resilient top predator following ecosystem fragmentation. Ecology Letters 10: 937–944.

Liermann, C. R., C. Nilsson, J. Robertson & R. Y. Ng, 2012. Implications of dam obstruction for global freshwater fish diversity. BioScience 62: 539–548.

Liew, J. H., H. H. Tan & D. C. J. Yeo, 2016. Dammed rivers: impoundments facilitate fish invasions. Freshwater Biology 61: 1421–1429.

McCann, K. S., J. B. Rasmussen & J. Umbanhowar, 2005. The dynamics of spatially coupled food webs. Ecology Letters 8: 513–523.

Maruyama, A., Y. Yamada, M. Yuma & B. Rusuwa, 2001. Stable nitrogen and carbon isotope ratios as migration tracers of a landlocked goby, Rhinogobius sp. (the orange form), in the Lake Biwa water system. Ecological Research 16: 697–703.

Matthews, B. & A. Mazumder, 2003. Compositional and interlake variability of zooplankton affect baseline stable isotope signatures. Limnology and Oceanography 48: 1977–1987.

McAllister, D. E., J. F. Craig, N. Davidson, S. Delany & M. Seddon, 2001. Biodiversity Impacts of Large Dams. vol Background Paper Nr. 1. IUCN/UNEP/WCD, 68.

Minagawa, M. & E. Wada, 1984. Stepwise enrichment of 15N along food chains: further evidence and the relation between δ15N and animal age. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 48: 1135–1140.

Nilsson, C., C. A. Reidy, M. Dynesius & C. Revenga, 2005. Fragmentation and flow regulation of the world’s large river systems. Science 308: 405–408.

Okuda, N., T. Takeyama, T. Komiya, Y. Kato, Y. Okuzaki, J. Karube, Y. Sakai, M. Hori, I. Tayasu & T. Nagata, 2012. A food web and its long-term dynamics in Lake Biwa: a stable isotope approach. In Kawanabe, H., M. Nishino & M. Maehata (eds), Lake Biwa: Interactions between Nature and People. Springer Academic, Amsterdam: 205–210.

Okuda, N., K. Watanabe, K. Fukumori, S. Nakano & T. Nakazawa, 2013. Biodiversity in aquatic systems and environments: Lake Biwa. Springer, Tokyo.

Pace, M. L., J. J. Cole, S. R. Carpenter, J. F. Kitchell, J. R. Hodgson, M. C. Van de Bogert, D. L. Bade, E. S. Kritzberg & D. Bastviken, 2004. Whole-lake carbon-13 additions reveal terrestrial support of aquatic food webs. Nature 427: 240–243.

Peterson, B. J. & B. Fry, 1987. Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 18: 293–320.

Poff, N. L., J. D. Olden, D. M. Merritt & D. M. Pepin, 2007. Homogenization of regional river dynamics by dams and global biodiversity implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104: 5732–5737.

Stockwell, C. A., A. P. Hendry & M. T. Kinnison, 2003. Contemporary evolution meets conservation biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18: 94–101.

Taipale, S., P. Kankaala, M. Tiirola & R. I. Jones, 2008. Whole-lake dissolved inorganic 13C additions reveal seasonal shifts in zooplankton diet. Ecology 89: 463–474.

Terashima, A., 1980. Bluegill: a vacant ecological niche in Lake Biwa. In Kawai, T., H. Kawanabe & N. Mizuno (eds), Japanese Freshwater Organisms: Ecology of Invasion and Disturbance. Tokai University Press, Tokyo: 63–70.

Tseng, Y. F., T. C. Hsu, Y. L. Chen, S. J. Kao, J. T. Wu, J. C. Lu, C. C. Lai, H. Y. Kuo, C. H. Lin, Y. Yamamoto, T. A. Xiao & F. K. Shiah, 2010. Typhoon effects on DOC dynamics in a phosphate-limited reservoir. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 60: 247–260.

Uchii, K., N. Okuda, R. Yonekura, Z. Karube, K. Matsui & Z. Kawabata, 2007. Trophic polymorphism in bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus) introduced into Lake Biwa: evidence from stable isotope analysis. Limnology 8: 59–63.

Vadeboncoeur, Y., D. M. Lodge & S. R. Carpenter, 2001. Whole-lake fertilization effects on distribution of primary production between benthic and pelagic habitats. Ecology 82: 1065–1077.

Vadeboncoeur, Y., M. J. Vander Zanden & D. M. Lodge, 2002. Putting the lake back together: reintegrating benthic pathways into lake food web models. BioScience 52: 44–54.

Vadeboncoeur, Y., E. Jeppesen, M. J. Vander Zanden, H.-H. Schierup, K. Christoffersen & D. M. Lodge, 2003. From Greenland to green lakes: Cultural eutrophication and the loss of benthic pathways in lakes. Limnology and Oceanography 48: 1408–1418.

Vadeboncoeur, Y., G. Peterson, M. J. Vander Zanden & J. Kalff, 2008. Benthic algal production across lake size gradients: Interactions among morphometry, nutrients, and light. Ecology 89: 2542–2552.

Vander Zanden, M. J. & Y. Vadeboncoeur, 2002. Fishes as integrators of benthic and pelagic food webs in lakes. Ecology 83: 2152–2161.

Vander Zanden, M. J., J. M. Casselman & J. B. Rasmussen, 1999. Stable isotope evidence for the food web consequences of species invasions in lakes. Nature 401: 464–467.

Vander Zanden, M. J., S. Chandra, B. C. Allen, J. E. Reuter & C. R. Goldman, 2003. Historical food web structure and restoration of native aquatic communities in the Lake Tahoe (California–Nevada) basin. Ecosystems 6: 274–288.

Vander Zanden, M. J., Y. Vadeboncoeur & S. Chandra, 2011. Fish reliance on littoral-benthic resources and the distribution of primary production in lakes. Ecosystems 14: 894–903.

Wu, J. T. & J. W. Chou, 1998. Dinoflagellate associations in Feitsui Reservoir, Taiwan. Botanical Bulletin of Academia Sinica 39: 137–145.

Wu, S. C., Y. C. Chien, C. J. Wu & J. S. Chiu, 2007. Identification of Physical Parameters Controlling the Dominance of Algal Species in a Subtropic Reservoir. The Graduate Institute of Environmental Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei: 10.

Yamada, Y., T. Ueda, T. Koitabashi & E. Wada, 1998. Horizontal and vertical isotopic model of Lake Biwa ecosystem. Japanese Journal of Limnology 59: 409–427.

Yonekura, R., K. Nakai & M. Yuma, 2002. Trophic polymorphism in introduced bluegill in Japan. Ecological Research 17: 49–57.

Yoshimura, S., 1937. Limnology. Sanseido, Tokyo: 520.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Japan-Taiwan Joint Research Program of Interchange Association, Japan, the JSPS Grant-in aid (No. 24405007 and 16H05774) and RIHN Project (D-06-14200119). FS was funded by RCEC-Academia Sinica. We thank the staff of the Research Center for Environmental Changes, Academia Sinica and Institute of Oceanography, National Taiwan University for their field assistance. We also thank Hiromi Uno and Shohei Fujinaga for their laboratory assistance. Masayuki Itoh generously provided his unpublished data on δ13C of CO2. The stable isotope analysis was conducted with Joint-Use Facilities of the Center for Ecological Research, Kyoto University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Handling editor: Michael Power

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Okuda, N., Sakai, Y., Fukumori, K. et al. Food web properties of the recently constructed, deep subtropical Fei-Tsui Reservoir in comparison with the ancient Lake Biwa. Hydrobiologia 802, 199–210 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3258-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3258-4