Abstract

Since 2005, major donors have been expanding Morocco’s programs to combat poverty, social exclusion and gender inequality. Yet, despite newly designed programs that advocate participatory approaches, empowerment and inclusion, rural women endure a persistent marginalization in development programs. This article explores the latest strategies of the Green Morocco Plan (GMP) and the income generating activities (IGA) strategies that seek to support the employment and autonomy of rural women. Interviews and focus groups were conducted with women in seven villages in Rhamna province and with key official informants. The study shows that the women’s participation in income generating activities and rural cooperatives’ decision-making processes is virtually non-existent and that empowerment and gender equality is not unfolding for women. Rather, the women’s involvement in running cooperatives is limited to providing cheap or even free manual labor, while only literate and generally educated people are able to benefit economically from the cooperative structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gender equality and women’s empowerment are central notions in current development discourse and key features of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the more recent SDGs (SDG 2017). Portrayed as a solution to remedy problems of women’s inclusion (Cornwall and Brock 2005; Cornwall 2016; Kabeer et al.2013), gender equality and empowerment stand high on the agenda of policy makers, especially for developing countries. Typically, criteria like access to aid, education, and health care, economic status, and equal participation in decision-making feature in the discourse of gender equality and empowerment (Potter 2013). It is often assumed that these can be gained from economic development (Hanmer and Klugman 2016). However, the assumption that empowerment can be gained through economic development has received much criticism (Cornwall and Edwards 2010; Grabe 2012; Hanmer and Klugman 2016; Kabeer et al.2013; Potter 2013). The authors point out that financial income does not suffice to trigger equality nor does it address the root cause of poverty. They emphasize that women’s empowerment is highly contextual and dependent on cultural structures of constraints and limitations and goes beyond material acquisition. In fact, relying on westernized notions of gender equality and external forms of governance in disadvantaged communities might be counterproductive. This can hinder women’s ability to exercise their inherent authority and influence on decision-making within their own cultural environment, and renders them vulnerable and undermined in their own communities (Hunt and Smith 2007). Most policy makers however pursue the economic agenda and encourage the integration of rural women in economic development as women are increasingly perceived as vital actors for the benefits of future generations (World Bank 2017).

As globalization is permeating even the most remote places on the planet, supported by neoliberal policies that seek to open markets of land, water, new commodities, and non-traditional exports (Laurie et al.2005), the commoditisation of natural products derived from natural resources is flourishing. Developing countries apply various national strategies that aim to meet the market demands and in which the participation of women is strongly anticipated.

Morocco, as a global player and leading nation in the North African region, has in recent years become a prominent player on the international economic and foreign political scene. Its influence on the rest of the Maghreb region and the Arab world has allowed the country to become a strong negotiator with outside powers to access aid and to pursue its internal socio-economic development agenda (Catusse 2009; Hettne and Soderbaum 2005).

However, despite receiving substantial external financial aid to combat poverty and social exclusion from institutions like the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Global Environment Facility (GEF), the German development cooperation (known as GIZ), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the European Union (EU), the country shows some important disparities in the domains of economic growth and employment, development, education and poverty (Chauffour 2018). Rural women in particular are poorly integrated in Moroccan society mostly due to poor education, and a lack of local economic opportunities. Two and a half million rural children are illiterate, particularly girls, and 83% of the total population in rural environments are still illiterate. Uneducated women account for 79% of Morocco’s rural labor force, a rate which can exceed 90% in mountainous areas (Euromed 2006; IFAD 2014). In contrast, 63% of women in the urban areas start working at the age of 20, and only 5% of women have unremunerated work (Achy and Belarbi 2015).

Because labor laws are not widely applied, rural women are generally poorly paid or not paid at all, and have no official employment status in domestic services and agriculture. This situation is exacerbated by limited access to land, a lack of female political representation, and the shifting of control over natural resources from women to men as these resources enter international markets. Furthermore, as in many other under-developed or developing countries, women’s entrepreneurship in natural resources and agricultural activities remains limited as decision making and power remains in formal, male dominated networks (Upadhyay 2005). As a result of such gender-based discrimination, and despite making up a large percentage of the workforce in rural areas, women persistently experience lower productivity, low income and higher levels of vulnerability and poverty (Quisumbing and Pandolfelli 2009).

We now turn to the Green Morocco Plan (GMP), Morocco’s main agricultural strategy for 2008–2020. It aims to position the development of the agricultural sector as a driving force for economic growth, offering investment opportunities for export-oriented agriculture (ADA 2016; Badraoui 2014; Medias 24 2015; Moroccan Investment Development Agency 2017; World Bank 2014) and by the same token to overcome the issues of poverty, unsustainable natural resource management, the negative effects of climate change, and women’s exclusion. The GMP rests on two “pillars” of reforms. The first pillar focuses on stimulating the growth of an export-oriented agriculture based on private investment. The second pillar is focused on supporting smallholder farmers through developing sustainable natural resources and women’s employment towards gender equality and socio-economic development in the most isolated parts of the country. To execute the second pillar, the government is implementing projects in four categories: (i) the conversion of existing crops or extensive production chains into sectors with high added value, (ii) the intensification of agriculture to improve productivity, (iii) the certification, processing, and labeling of local products, and (iv) the diversification of agricultural income sources to benefit farmers or members of their families (Duporte 2014).

Because gender equality is prevalent in the agenda of most donor agencies and policy-makers, the Moroccan government is under pressure to integrate women in economic development, particularly in rural areas. Extra measures have therefore been included in the GMP to strengthen the attitudes and engagement of stakeholders and partners with regard to poverty, gender equity and women’s empowerment. For example, the GMP includes a number of measures to facilitate women’s access to income generating activities (IGA) through the promotion of cooperatives for agricultural products and services (Balaghi et al.2012). This is supported by a series of measures that specifically target women in order to encourage their participation in local bodies and committees. According to Belghiti (2013) and the ONDH (2005), a review of government documents (including those preceding the GMP) reveals that economic empowerment is expected to unfold through access to and control of productive assets and an increase in household wealth. The plan is to strengthen women’s decision-making powers at the household and community level, so as to alleviate their overall workload and to make it more balanced between them and men. Last but not least, the government wants to ensure that development projects pay particular attention to gender equity and empowerment aspects. It emphasizes that all efforts will be deployed to reach women with an adequate number of qualified staff to dispense awareness training and involve them in all the implementation stages of a given project (Belghiti 2013; ONDH 2005).

While this sounds promising in theory, the GMP has however raised some serious concerns. Some of them are of a more general nature. For example, Akesbi (2011, 2012) has critiqued the GMP’s design by the consulting firm McKinsey for its dominant productivist and technicist vision. Faysse et al. (2014) have discussed the conflicts that emerge over tree plantations between local farmers following external entrepreneurs’ interventions. Faysse (2015) has also pointed to the missing links between the GMP goals and its implementation mechanisms at the local level. When it comes to women’s involvement, Berriane (2011), Damamme (2014), and Perry et al. (2018) have shown the minor roles that illiterate rural women hold in the cooperatives compared to women of higher status and responsibilities. Apart from these studies though, not much is known about the effects of women’s income-generating activities (IGA) at the village level which are implemented as part of the GMP’s Pillar II. Using an ethnographic approach, this article aims to fill this void.

The study on which this article is based aimed to identify the effects of the current Pillar II initiatives of the GMP on women’s wellbeing and status in the case of Rhamna province in Morocco. The findings – discussed in more detail below –shows that although some women have joined several cooperatives, they are recruited as a cheap, or sometimes even free, labor force and are not able to participate actively in any decision-making processes. In addition, only literate, educated people are able to create the required cooperative structures for the creation of income generating activities.

Indeed, our findings on the initiatives of the Pillar II reveal a four-layered system. The first layer promotes a “business as usual” type of economic incentives to supply large (international) markets, benefiting the most educated and financially viable people and organizations; a second layer benefits the educated people within the community but who are somewhat constrained by the lack of commercial knowledge and openings for trade ventures in a saturated product market. Then follows a layer in which the less educated and financially disadvantaged but resourceful people find the means to hook into the initiatives and finally, a layer which fails to include the most deprived and vulnerable people as witnessed in the most isolated villages. These disparities not only contribute to reinforcing the poor status of women working in the cooperatives but maintain the inequalities and poverty gaps.

The article is organized as follows. The next section sets out the context of the case study in terms of the institutional framework currently in place to implement the GMP’s second pillar initiatives and the income generating activities schemes (IGA) and key characteristics of Rhamna province. This is followed by a section detailing the research methodology. The article then analyses the situation of women in the villages targeted by the GMP in the province of Rhamna and presents the findings on the role and position of women in the running of cooperatives.

The Case Study: Policy and Institutional Context

Morocco has been trying to overcome the country’s pressing issues of poverty, economic stagnation, illiteracy, gender inequality, and the poor living conditions in the country’s urban slums and most deprived areas for some decades. However, since the ascension of King Mohamed VI to the throne in 1999, the monarch and his government have made more concerted efforts to alter the status of the country and improve its economic development (Chauffour 2018). In 2005, the National Human Development Initiative (INDH) was launched with a budget of $100 million to address poverty, unemployment, and lack of physical infrastructures. It is currently in its third phase (2016–2020) (Communes et villes du Maroc 2018). The INDH has in the past few years contributed to the creation of local village associations and more recently to rural cooperatives. As a partner of the IGA schemes, the INDH supplies equipment to cooperatives provided that people are able to request and fulfil the administrative formalities.

As mentioned earlier, in the field of agricultural development, the Green Morocco Plan (GMP) 2008–2020 aims to address issues of poverty, climate change, food security, natural resource conservation and the general challenge of women’s employment and social integration. The plan rests on two “pillars” of reforms. The first one is designed to achieve an accelerated development towards a modern and competitive export-oriented agriculture, relying on projects with high added value in agro-industries and private investment. With an investment of 75 billion Dirham (US$ 7 billion), this first pillar is expected to accomplish 962 projects by 2020 and to benefit 560,000 farmers. The second pillar, which is the focus of this study, aims to support the transition of smallholder farmers from traditional family farming to more modern farming practices through reconversions, intensifications and diversifications of local natural resources which are aimed to ensure sustainable natural resource use and women’s employment in the most isolated parts of the country. With an allocated budget of 20 billion Dirham ($ 2 billion), it foresees the creation of 545 social projects which are geared to help 860,000 smallholder farmers to transit from traditional subsistence agriculture to more intensive forms of agricultural production (Duporte 2014; Laatar 2014). Besides the two pillars, a number of cross cutting strategic actions are being implemented. These relate to the management and privatization of public and collective lands within a framework of public private partnership (PPP); this is thought to encourage structural reforms through the acceleration of land registration; the rational and sustainable water management including the spreading of modern irrigation techniques and the creation of a water pricing system; the adoption of an offensive strategy to enter foreign markets, the modernization of distribution channels and the improvement of access to wholesale markets; and finally, the reform and strengthening of the Ministry of Agriculture and the government’s supervisory functions in the area of agriculture (Ministry of Agriculture 2014).

For the GMP to be effective the government has deployed an important array of reforms within the Ministry of Agriculture and the Chambers of Agriculture and the creation of structures for social proximity services (Akesbi 2011). The latter refer to several local, regional and provincial structures responsible for the implementation of agricultural programs: Regional Agricultural Development Offices (Office Régional de Mise en Valeur Agricole [ORMVA]) and new agencies such as the Agricultural Development Agency (Agence pour le Développement Agricole [ADA]) which provides substantial financial and human resources (and includes a directorate for the development of “Terroir” products); the National Agency for the Development of Oasis and Arganier Areas (Agence Nationale de Développement des Zones Oasiennes et de l’Arganier [ANDZOA]); and the Office National de la Santé Sanitaire des Aliments (ONSSA) for the regulation and control of food safety standards. Other actors work at the local level to implement small-scale projects with the farmers. In the Province of Rhamna, these actors include the INDH, the Social Development Agency (Agence de Developpement Social [ADS]), the Provincial Directorate for Agriculture (Direction Provinciale de l’Agriculture, [DPA]), the National Office of the Council for Agriculture (Office National du Conseil Agricole, [ONCA]), the Foundation of the mostly state-owned OCP Group (a global market leader of phosphate and its derivatives), as well as the Rhamna Foundation for Sustainable Development, a local NGO.

The Case Study: Key Characteristics of Rhamna Province

The province of Rhamna was created in March 2010 following a division of the former province El Kelaa des Sraghna. It belongs to the region of Marrakech-Safi at the border of the Wilaya of Marrakech and the provinces of Settat, Sidi Behera, Safi, Youssoufia and El Kelaa des Sraghna, and covers an area of 5856 km2 with a population of 288.437 inhabitants. Due to its geographical location, it occupies a strategic place in the centre of the country and constitutes a crossroads between the North and the South, connected by a national road (RN 9) from Marrakech to Casablanca. The province is rich in phosphate which is managed by the OCP. It is home to the only military base in the country. Politically, Rhamna province is dominated by the Parti authenticité et modernité (PAM), a conservative party created by Fouad Ali El Himma, a native of the province and close friend and advisor to the King (Zerr 2017). The province’s capital city, Benguerir, is favored by the king and under his auspices the city is to become the first Mohamed VI Green CityFootnote 1 in Africa.

However, despite such royal patronage, the province’s education system has failed to eliminate illiteracy. Individual migration is seen as the most effective means to advance socially and to improve one’s living conditions. The enrolment rate in schools is low, significantly below the national average, at around 40% for boys and 60% for girls. Illiteracy is especially high in the North of the province, with rates exceeding 60% for men and 75% for women (Monographie Generale-Region de Marrakech-Safi 2015). Women who tend to be responsible for the daily subsistence are particularly keen to be educated and seek income to pay for their children’s education, while men tend to be more reluctant to send their children to secondary education as the children (once they leave primary school) are often needed to participate in the household chores and work in the fields and gardens (Montanari 2013; 2014).

Given the remoteness of the villages in the province, half of the villages are connected by photovoltaic kits; however, the electricity connections for basic structures like schools and health centres remain insufficient. The availability of drinking water is also problematic for nearly half the municipalities and shows large disparities from one commune to another. In some villages, it is not uncommon for women to spend most of their day waiting for water to become available at the village fountain or fetch it at the next source a few kilometers away (field conversation with women and personal observation in a village). The authorities hope that building the capacity of local associations with the support of communes and technical services of the Office National d'Electricité et de l'Eau Potable (ONEE) will improve water management and provision (Monographie Generale-Region de Marrakech-Safi 2015).

In terms of subsistence, the local populations depend mainly on cereal cultivation which covers 98% of the cultivated land and which is increasingly affected by drought. The average yields are insignificant and do not exceed eight quintals per hectare. Wheat (soft and hard), barley, corn, legumes, peas, lentils, chick peas, alfalfa, and oats are the main cereal and legume crops along with vegetable crops like potatoes, tomatoes, onions and Cucurbaceae species. The local people typically practice traditional transhumance and rear ovine like the Sardi goat-mutton, a local species whose meat is widely appreciated and in high demand (N Excel Consult 2009).

Methodology

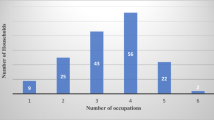

The first author conducted field research in the province of Rhamna, located 75 km north of Marrakech, between June and August 2016. The province was chosen because of its high poverty level and its high priority for development as identified and targeted by the authorities. Prior to arriving in the province, a literature review (articles and internet documentation in English and French) was conducted to identify the relevant initiatives of the GMP. Although the web provides numerous articles on the GMP (for example, Agence de Développement Agricole 2016; Green Morocco Plan 2016; Le Matin.ma 2012; Ministry of Culture and Communication 2017; Moroccan Investment Development Agency 2017; Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests 2015; World Bank 2017); little information on the initiatives however was available for Rhamna province. To give a better representation of the sample, seven villages were selected from the northern, central and southern parts of the province from a list suggested by the regional director of the ONCA. The choice of villages was also based on cooperatives which had been recently created and on the villages in the surrounding area still struggling to start initiatives. Although most cooperatives were created between 2008 and 2010 with the exception of B2 which was created as early as 2006; the actual running varies as the funding, equipment and furbishing, can take anything from one to two years. The women are recruited from the surrounding villages and there is no informal registration rather the names are just written down in a register. The interviews and focus groups were conducted with groups of women in each cooperative located in a village (Table 1); a total of 69 women participated in eight focus groups in the presence of the cooperative managers. As it was difficult to gather all the women at the same time, the managers facilitated the assembly in the cooperative building. We cannot be entirely sure about the effects of the presence of the managers on the women’s responses, but they seemed mostly positive, as the managers encouraged the women (who are not used to talking to foreigners) to voice their opinions.

In addition, to gain the trust of the cooperative members, the first author explained that the research aimed to understand how the women integrated the cooperatives, to witness the working conditions in the work place and to understand how the conditions could be improved for increasing the enrolment of women. As they did not wish to be recorded, the first author took detailed notes. The interviews and group focus discussions lasted for an hour on average and were held in Arabic with the support of a local research assistant and then translated into French. In the cooperatives, the focus group discussions sought to elicit the women’s perception of the initiatives, how they viewed their participation in the initiatives, their opinions about earning money, and how they used it. The discussions further enquired about the conditions of the households, the education of the children and the changes that occurred in the households because of their employment as well as their overall aspirations.

In addition to the interviews and focus groups with the women, the cooperative managers were also interviewed. The managers of cooperatives B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 are two educated men and three educated women respectively with an employment history in government offices; the managers of B6 and B7 on the other hand are family-based and have no particular education or employment. Interviews sought to elicit the role of managers, their ambitions to develop the cooperatives, and how they saw the participation of the women in the cooperatives.

In addition, semi-structured key informant interviews were also conducted with representatives of government institutions, i.e., the Director of the Direction Départementale de l’Agriculture (DPA); the regional director of the Office National du Conseil Agricole (ONCA); the secretary of Rhamna Foundation working in the Province as well as the regional director of the Agence de développement social (ADS) in Marrakech. The key informant interviews were conducted in French as it is the official second language in Morocco. On average, they lasted an hour and took place in the interviewee’s office. Moreover, the first author had several subsequent informal meetings, especially with the Director of the DPA and the Director of the ONCA, as well as the Secretary of Rhamna Foundation. These conversations covered the role of these institutions in the implementation of the initiatives, how the interviewees perceived the role of women and the encountered difficulties and what measures were available to integrate them in the activities.

Findings and Discussion

Lack of women’s Involvement in the Creation of Cooperatives

Cooperatives are thought to be important structures for socioeconomic development. According to Ibourk and Amaghouss (2014), Morocco has 1512 operational women’s cooperatives spread over 74 provinces, out of which 210 (or 14%) are Argan oil cooperatives. Some level of education is imperative for the creation of cooperatives. The seven cooperatives in our sample are managed by both educated women and men. They have different levels of education and are occupying or have occupied various professional functions. Education facilitates the handling of the administrative procedures and securing the financial requirements, which illiterate rural women are not able to do. Also, one of the main criteria prescribed by the IGA guidelines is that the administrative bureau includes like-minded people. In our fieldwork, we observed that the administrative bureaus of the cooperatives often included members of a same family and/or close connections. This ranged from sisters, close friends or female extended family for the cooperatives run by women, to wives, daughters, aunts and even grand-daughters for cooperatives run by men. This not only facilitates the creation of a structure with a readily available network but also eases the decision-making processes as the manager is able to take unilateral decisions and impose his/her views on the other members.

Women’s Motivations

In order to understand women’s motivations work in a cooperative, it is useful to consider women’s aspirations for change. For rural women living in isolated villages and limited by local traditional norms, yet influenced by a westernised way of life (through TV and other media), the possibility of gaining equality, empowerment and financial autonomy are attractive features. Women in the villages expressed their will to work and to earn money. However, they are not able to start a project of their own because the creation of a cooperative requires a number of administrative formalities that they cannot fulfill given their illiteracy and the requirement of an initial financial contribution that they cannot provide. They are particularly keen to provide a good education for their children and to improve life in the household. As this woman in village B1 said: “We want to provide better education for our children, start our own projects and gain some financial independence rather than just depend on our husbands.” However, because of cultural norms, women tend not to go far from the villages. Most men were happy to have their wives working within village boundaries. As most men in the villages are seasonal workers beside their transhumance activities and the male labor migration to the cities is saturated (Damamme 2014), the extra income is welcomed. Representatives of official institutions like the DPA and the ONCA in Benguerir recognized that the integration of women in cooperatives was vital. However, the DPA director admitted that enrolling the rural women was not straightforward (Interview 1): “The integration of women in projects is vital. Previously, it was only single, widowed women who became members in the associations/cooperatives. However, there is a gradual change of mentality between men and women. Now, even married women are able to engage in projects. Women work hard and they go for the money because of the poverty, and for what they can earn immediately, but there is no long term vision, only short term. A central pillar [preferably someone local and educated who can act as a leading figure] is absolutely necessary to engage women.”

Women’s Recruitment

The women employed in the cooperatives tend to be recruited from the close surrounding villages and usually work in teams of eight and in shifts. In the cooperatives run by female managers, the women perform various tasks like harvesting, cleansing of seeds (coriander, quinoa, nigella and poppy seeds, colza, sesame and millet) and packing (e.g. cooperative B1). In this cooperative, the women are working but are not paid; rather they are expected to just “give a hand”. Women are also enrolled in cooperative B2 for the production of aromatized couscous for which they are paid 5Dh per kg of couscous produced. In another cooperative that produces honey, they proceed to honey collection for which they are remunerated up to 50Dh per day (approx $ 5.45) (informal exchange with president of the cooperative B3). The organization is the same for women working in the cooperatives run by men, as they work in groups and in shifts. Women are employed for the cleansing of cumin seeds in a cumin cooperative (B4), and remunerated between 40 to 50 Dh daily; for the collection, cleansing and processing of the cactus fruit in a cactus cooperative (B5), women are paid 50 Dh per day for approximately six to eight hours of work and an extra 20Dh for each kg of cactus fruit seeds delivered. The seeds are then extracted for oil. While the two latter cooperatives (cumin and cactus) manage to produce a finished product, they lack training in marketing and thus struggle to access international markets, especially as these tend to be saturated with similar products. Two much smaller operations are a quinoa cooperative (B6), a husband-and-wife operation involved in the growing, collecting and cleansing of quinoa seeds. Women from the nearby village are occasionally hired for their services and remunerated approximately 40 to 50 Dh daily, depending on the work provided. Another small cooperative (B7) is involved in the production of honey. The man who owns the cooperative employs his mother and his sisters-in-law for collecting honey from the hives. The women are not remunerated.

Women’s Lack of Status

A main objective of the study was to identify whether women were able to be part of the decision-making processes as prescribed by the government in the income generating activities (IGAs) schemes. Most policies are based on the assumption that gender equality and empowerment come about through participation in decision-making and economic incentives (Cornwall 2016; Potter 2013). However, with the exception of the honey cooperative where women are allowed to participate in the annual general assembly as per the Office de Développement de la Coopération (OCDO) legislation, the fieldwork analysis revealed that the women employed in the other cooperatives do not participate in the decision-making processes. In addition, in structures like cooperative B1, women are not remunerated but “just giving a hand”; there is no legal recourse that villagers are aware of by which the women could manifest their discontent or claim their rights. As Damamme (2014: 94) pointed out, “women working in cooperatives represent just a labor force.” Similarly, in her impact evaluation of women cooperatives in the Argan oil sector which received INDH funding, Perry et al. (2018:13 and 20) found that ‘most workers reported modest financial gains’ and that they were ‘often vulnerable to exploitation, crime, and venture failure, particularly when managers lacked basic skills’. In addition, membership in an Argan cooperative did not make any difference to women’s literacy levels (ibid: 20). Also in our study, we found that the women’s poorly paid or unremunerated labor that they provide is invisible and unrecognized. What tend to be prized instead are the highest levels of intervention in the production chains, i.e., managers and technicians. However, this contrasts with the official discourse which states that the government’s primary goal is to pull the women out of the image of “backward tradition” characterized by illiteracy. The discourse also conveys an image that women are able to engage in decision-making processes and integrate modern forms of production. It is clear that the enrolment of women in cooperatives – at least on paper- improves the official statistics of the “income generating activities” schemes and wage labor, both in the cities and increasingly outside of them. The enrolment figures also serve to justify intervening in support of the deprived rural female labor. Based on our findings, we have reasons to be skeptical about the potential of rural women’s cooperatives serving as stepping stones for empowerment and gender equality. Although the director of the ADS in Marrakech claimed that 334 cooperative projects were ongoing with an estimated 95% success rate, this corresponds to the enrolment of educated young women geographically close to urban centers, who are able to fulfill the administrative requirements, and to follow training programs (personal coaching, soft skills, IT, technical support and capacity building) supported by government structures like Rhamna Skills hosted by the Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP) in Benguerir to facilitate employability. While these published figures may serve the ADS and government in terms of official statistics, they do not necessarily represent successful medium or long-term projects, nor do they guarantee women’s steady incomes, socio-economic development or any kind of equality and empowerment.

Conclusion

This article identified and analyzed the flaws and mechanisms that prevent the equitable participation of women in the IGAs of cooperatives in the context of the Pillar II of the GMP. It focuses in particular on the lack of participation in decision-making in the cooperatives for the rural women in the province of Rhamna. The findings should be read against the background of the GMP’s general outlook, which is privileging an economic agenda based on the development of public private partnerships (PPP) in large economic ventures. In this agenda, Pillar II projects which are primarily designed for the poorest populations are sidelined to prioritize initiatives that favor the exploitation of resources on private land and that converge towards bigger lucrative actions. Based on our fieldwork findings, it seems that only educated people in the region are able to benefit from Pillar II projects, given the administrative burden and the initial financial contribution that needs to be deposited. In addition, in villages where women are recruited into cooperatives, the women are employed as a cheap or even free labor force under the managing directives of educated people who are in a prime position to create cooperative structures. As for the claim that the women are able to gain empowerment, beside the small income that a handful of women are able to earn in cooperatives B 2, B3 and B4, women do not enter into any decision-making processes; only their labor justifies their enrollment. Rather the way that external directives are designed and applied are not intended to provide the space for women to voice their needs and aspirations, nor do they reflect the local experiences and daily realities. This study thus confirms Duflo’s (2012:1076) finding that ‘economic development alone is insufficient to ensure significant progress in important dimensions of women’s empowerment, in particular, significant progress in decision-making ability in the face of pervasive stereotypes against women’s ability.’

Indeed, our findings help corroborate the relevance of the gender and work framework developed by Rao and Kelleher (2005:60), which argued that gender equality can only come about if change occurs in formal and informal institutions at both the personal and the societal/systemic level. While the importance of formal institutions such as women’s access to rights and resources, and relevant laws and policies are generally acknowledged by international and domestic policy makers, the significance of informal institutions is not yet widely recognized. By the latter, the framework refers to women’s and men’s individual consciousness (knowledge, skills, political consciousness, commitment); as well as informal norms, such as inequitable ideologies, and cultural and religious practices.

We therefore argue that an authentic empowerment for women at community level can only emerge through a shift of consciousness, one that builds on new belief systems revolving on the cultural and socio-political environmental context; one that bypasses the perception that rural women are unable to assume their own economic development. While we agree with Perry et al. that education has a role to play (2018:22); we are claiming that for women to be able to gain confidence, a tailor-made pedagogy is required. From our findings, it seems that Morocco’s GMP is replicating the widely criticized Women in Development (WID) approach of the 1970s in that most WID programs demanded women’s participation, often in the form of unremunerated labour, ‘in activities which proved[d] not to meet their needs or whose benefits they [did] not control.’ (Leach 2007:72 cited in Cruz-Torres and McElwee 2012:7).

In addition, we believe that the GMP initiatives can only produce equitable outcomes in an environment in which there is trust between government agents, local leaders, and the local populations, and which respects the community’ s cultural and traditional norms. By pointing to the limitations in the GMP with regard to the implementation of IGAs in the most isolated villages, the article fills an important gap in the analysis of policies which seek to address gender equality and empowerment, employment and the well being of rural women in socio-economic development in isolated and difficult environments.

Notes

Benguerir is to become the first Green City of the country under the patronage of Mohamed VI. According to the OCP website, the city is currently developing a future world-class university and will be offering a high quality way of life in an ecological environment. http://www.ocpgroup.ma/sustainability/green-cities.

References

Achy, L. and A. Belarbi. (2015). Egalité économique entre hommes et femmes? Economia http://economia.ma/sites/default/files/publicationPJ/Economia%20N%202.pdf (Accessed 18 Feb 2018).

Agence de développement Agricole (2016). http://www.ada.gov.ma/web/ (Accessed 11 Oct 2017).

Akesbi, N. (2011). « Le Plan Maroc Vert: une analyse critique».Questions d’économie marocaine, In: ‘Association marocaine de sciences économiques (ed), Rabat Presses Universitaires du Maroc, Rabat.

Akesbi, N. (2012). Une nouvelle stratégie pour l’agriculture marocaine: Le “Plan Maroc Vert” New Médit N° 2. http://newmedit.iamb.it/2012/04/10/une-nouvelle-strategie-pour-lagriculture-marocaine-plan-maroc-vert/ (Accessed 12 Sept 2018).

Badraoui, M. (2014). The Green Morocco Plan: An Innovative Strategy of Agricultural Development Environment and development. Journal AL-BIA WAL-TANMIA http://afedmag.com/english/ArticlesDetails.aspx?id=105 (Accessed 11 June 2018).

Balaghi, R., Jlibene, M., Benaouda, H., Kamil, H., and Debbarh, Y. (2012). Intégration du changement climatique dans la mise en œuvre du plan Maroc vert. Etude de l’impact environnemental et social du sous-projet PICCPMV: Reconversion des céréales en olivier sur une superficie de 1600 Ha dans la région de Chaouia-Ouardigha. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/936111468054557016/text/E27080FRENCH0v073B0MNA0EA0P117081v9.txt (Accessed 27 Aug 2017).

Belghiti, H. (2013). Approche genre et promotion de la femme rurale. Thèse pour l'obtention du Doctorat en Droit Public. Faculté des Sciences Juridiques, Economiques et Sociales. Laboratoire de recherche sur la coopération internationale et le développement. University Cadi Ayyad, Morocco.

Berriane, Y. (2011). Le Maroc au temps des femmes? La féminisation des associations locales en question. L'Année du Maghreb. Pp 333-342. CNRS Editions. DOI: 10.4000/ anneemaghreb.1270. https://journals.openedition.org/anneemaghreb/1270 (Accessed 23 Feb 2018).

Catusse, M. (2009). Morocco’s Political Economy. The Arab State and Neo-liberal Globalization. The Restructuring of State Power in the Middle East, Ithaca Press, pp185–216. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00553994 (Accessed 02 Sept 2018).

Chauffour, J.P. (2018). Morocco 2040: Emerging by investing in intangible capital. World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28442 (Accessed 12 Jan 2018).

Communes et villes du Maroc (Régionalisation 12). (2018). L'INDH aborde sa troisième phase. http://www.communesmaroc.com/province/khouribga/news/2016/04/khouribga-lindh-aborde-sa-troisieme-phase#news (Accessed 16 Jan 2018).

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development 28: 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3210 (Accessed 12 Sept 2018).

Cornwall, A., and Brock, K. (2005). What Do Buzzwords Do for Development Policy? A critical look at participation, empowerment and poverty reduction. Third World Quarterly 26(7): 1043–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590500235603 Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

Cornwall, A., and Edwards, J. (2010). Introduction: Negotiating Empowerment. IDS Bulletin 41(2): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00117.x (Accessed 29 Sept 2018).

Cruz-Torres, M. L., and McElwee, P. (2012). Introduction: Gender and Sustainability. In Cruz-Torres, M. L., and McElwee, P. (eds.), Gender and Sustainability: Lessons from Asia and Latin America. The University of Arizona Press, pp. 1–25.

Damamme, A. (2014). La difficile reconnaissance du travail féminin au Maroc : Le cas des coopératives d’huile d’argan. In: Guerin I., Hersen M., et Fraisse L. (eds.), Femmes, économie et développement : De la résistance à la justice sociale. IRD/IRES Editions, Paris and Toulouse, pp. 87–106.

Duflo, E. 2012. Women Empowerment and Economic Development Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 50, 4:1051–1079 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23644911 (Accessed 21 Nov 2018).

Duporte, S. (2014). La mise en œuvre d’une agriculture solidaire au Maroc : Entre impératif écologique et viabilité économique. L’exemple des projets de reconversion de la sole céréalière en arboriculture fruitière à destination des petits agriculteurs dans la province de Taza. Master 2 Interdisciplinaire Dynamiques Africaines (MIDAF), Université Bordeaux –Montaigne, Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II, Maroc.

Euromed (2006). Role of Women in Economic Life Programme: Analysis of the economic situation of women in Morocco. http://www.euromedgenderequality.org (Accessed 21 July 2017).

Faysse, N. (2015). The Rationale of the Green Morocco Plan: Missing Links between Goals and Implementation. Journal of North African Studies 20: 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2015.1053112. (Accessed 11 Oct 2017).

Faysse, N., El Amrani, M., Errahj, M., Addou, H., Slaoui, Z., Thomas, L., et al (2014). Des hommes et des arbres : relation entre acteurs dans les projets du Pilier II du Plan Maroc Vert. Alternatives Rurales (1): 75–83 Accessed 04 Dec 2017.

Grabe, S. (2012). An Empirical Examination of Women’s Empowerment and Transformative Change in the Context of International Development. American Journal of Community Psychology 49(1–2): 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9453-y Accessed 05 Oct 2018.

Hanmer, L., and Klugman, J. (2016). Exploring Women’s Agency and Empowerment in Developing Countries: Where Do We Stand? Feminist Economics 22(1): 237–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1091087 Accessed 04 Oct 2018.

Hettne, B., and F. Soderbaum (2005). Civilian Power or Soft Imperialism? The EU as a global actor and the role of inter-regionalism. 10 European Foreign Affairs Review Issue 4:535–552. Kluwer Law International ISSN: 1384–6299

Hunt, J., and D. E Smith (2007). Indigenous Community governance project: Year Two Research Findings. CAEPR Working Paper No. 36. Australian National University (ANU) https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/145661 (Accessed 10 Nov 2018).

Ibourk, A., and Amaghouss, J. (2014). The Role of NIHD in Promoting Women Cooperatives in Morocco: A micro Econometric Analysis. Journal of Economics and Business Research 2: 95–114.

IFAD (2014). Programme de développement rural des zones de montagne (PDRZM), phase I. Volume I: Rapport principal et appendices https://operations.ifad.org/web/ifad/operations/country/project/tags/morocco/1727/documents (Accessed 07 Nov 2016).

Kabeer, N., Sudarshan, R., and Milward, K. (2013). Organizing Women Workers in the Informal Economy: Beyond the Weapons of the Weak, Zed Books, London.

Laatar, F. (2014). Le Fonds de développement agricole dans le cadre du Maroc Plan Vert : Essai pour une évaluation d’étape. Projet de fin d’études présenté pour l’obtention du diplôme d’Ingénieur en Agronomie. Filière : Economie et Gestion, Option : Ingénierie de Développement Economique et Social. Institut agronomique et vétérinaire Hassan II, Maroc.

Laurie, N., Andolina, R. and S. Radcliffe (2005). Ethno-development: Social Movements, Creating Experts and Professionalising Indigenous Knowledge in Ecuador. Antipode. https://doi-org.eur.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00507.x (Accessed 10 Oct 2018).

Le Matin. ma (2012). https://lematin.ma/journal/2012/Plan-Maroc-vert-La-province-de-Rhamna-jette-les-bases-d-une-agriculture-moderne-a-forte-valeur-ajoutee/174444.html (Accessed 02 Jan 2018).

Leach, M. (2007). Earth Mother myths and other ecofeminist fables: How a strategic notion rose and fell. Development and Change 38(1): 67–85.

Medias 24 (2015). Plan Maroc Vert: un bilan d'étape sous le signe de l'optimisme. https://www.medias24.com/ECONOMIE/ECONOMIE/154512-Plan-Maroc-Vert-un-bilan-d-etape-sous-le-signe-de-l-optimisme.html (Accessed 20 Feb 2018).

Ministry of Agriculture (2014). The Green Morocco Plan http://www.agriculture.gov.ma/en/pages/strategy (Accessed 14 Nov 2017).

Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests (2015). http://www.agriculture.gov.ma/en/pages/strategy (Accessed 22 Oct 2017).

Ministry of Culture and Communication. (2017). http://www.maroc.ma/en/content/green-morocoo-plan (Accessed 15 Nov 2017).

Monographie Generale-Region de Marrakech-Safi (2015). Region: Marrakech Tensift El Haouz. https://www.hcp.ma/region-marrakech/PRESENTATION-DE-LA-REGION-DE-MARRAKECH-SAFI_a248.html (Accessed 10 Feb 2019).

Montanari, B. (2013). The Future of Agriculture in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco: The Need to Integrate Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Chapter 5 in: S. Mann (ed), The Future of Mountain Agriculture, Springer Geography, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Pp 51–72.

Montanari, B. (2014). Environmental concerns, vulnerability of a subsistence system and traditional knowledge in the High Atlas of Morocco. Chapter 7 in: Bento-Gonçalves and Vieira (eds), Mountains: Geology, Topography and Environmental Concerns, Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge New York. ISBN: 978-1-63117-288-5. Pp 214–228.

Moroccan Investment Development Agency (2017). http://www.invest.gov.ma/?Id=25&lang=en&RefCat=5&Ref=148 (Accessed 30 Oct 2017).

N Excel Consult (2009). Stratégie de promotion socio-économique de la femme rurale dans la zone de Rhamna. Direction Provinciale de l’Agriculture El Kelaa des Sraghna.

ONDH (2005). Initiative Nationale pour le Développement Humain. Programme de lutte contre la pauvreté en milieu rural. http://www.ondh.ma/sites/default/files/documents/indh_rural_fr.pdf (Accessed 05 Dec 2017).

Perry, W., Rappe, O., Boulhaoua, A., et al (2018). Argan oil and the question of empowerment in rural Morocco. The Journal of North African Studies (online first). https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2018.1542596 (Accessed 18 Nov 2018).

Potter, E. (2013). Rethinking Women's Empowerment. Journal of Peace building & Development 8(1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2013.785657 Accessed 10 Oct 2018.

Quisumbing, A. R., and L. Pandolfelli (2009). Promising approaches to address the needs of poor female farmers: Resources, constraints, and interventions. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00882. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4678/6ad7e2cb9eca5c69b38cebe6560e4ec95b8f.pdf (Accessed 18 Oct 2017).

Rao, A., and Kelleher, D. (2005). Is there life after gender mainstreaming? Gender & Development 13(2): 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332287 Accessed 3 Dec 2018.

SDG (2017). Supporting the sustainable development goals. A Guide for Merit-Based Academies. InterAcademy Partnership. http://www.interacademies.org/IAP_SDG_Guide.aspx (Accessed 18 June 2019).

Upadhyay, B. (2005). Women and natural resource management: Illustrations from India and Nepal. Natural Resources Forum 29: 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2005.00132.x Accessed 08 June 2018.

World Bank (2014). http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/video/2014/01/24/supporting-small-farmers-in-morocco (Accessed 02 Nov 2017).

World Bank (2017). http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/morocco/brief/world-bank-involvement-in-the-agricultural-sector-in-morocco (Accessed 04 Jan 2018).

Zerr, M. (2017). Dans les pas de Fouad Ali El Himma, premier conseiller de Mohamed VI. http://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2007/09/08/01003-20070908ARTFIG90721-dans_les_pas_de_fouad_ali_el_himma_premier_conseiller_de_mohammed_vi.php. (Accessed 30 Nov 2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the local communities and local authorities for contributing to the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Commission under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions (grant number 657223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Montanari, B., Bergh, S.I. A Gendered Analysis of the Income Generating Activities under the Green Morocco Plan: Who Profits?. Hum Ecol 47, 409–417 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-019-00086-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-019-00086-8