Abstract

The Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en of Northwestern British Columbia formerly used landscape burning to manage patches of black huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum), the most important plant resource of their seasonal round. In view of its significance one might postulate that managed sites would conform to a biophysical or ecological type to maximize return for effort. However, a survey of a number of traditionally managed sites indicated that managed sites are characterized by wide variation in biophysical attributes including elevation, aspect and moisture regime, while proximity to fishing sites, village sites, or sites for harvest of alpine resources proved to be a common factor in known historic berry patch sites. We conclude that characterization of the ideal site type for aboriginal V. membranaceum management must include the economy and social institutions of the local First Nations and requires an enhanced appreciation for the sophistication of the strategies and techniques employed in their management and utilization of the species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

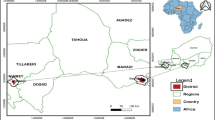

This map represents a general overview as it is not a complete inventory of traditional berry patches. It also does not show several village sites that are no longer occupied nor the numerous seasonal fishing sites and smokehouse locations along the rivers.

One of the factors that is not clear is whether “packloads” refer to fresh or dried fruit. The volume ratio of fresh to dried fruit is 10.25:1 which could create a ten-fold error in the projections. However, ethnographic information from interviews suggests that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, fruit was usually processed and dried on site and transported in dry form (Johnson fieldnotes and People of Ksan 1980).

Richard Daly (2005) indicates that there were 90 House groups in the early nineteenth century for the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en combined, yielding an estimate of 20.4 ha of productive berry ground for each house on a yearly basis.

Daly estimates a population of 100 people in each house group, for a total population of 8,000–10,000 for the two groups together before the impact of epidemics caused severe population reduction in the later nineteenth century. A set of conservative assumptions regarding actual numbers of pickers per house (we estimated 30) and duration of picking (we estimated 20 days of picking based on interview data from Olive Ryan reported in Johnson 1997:98) yields a quite reasonable harvest per day per person (7.4 US gallons) to obtain the estimated harvest. Contemporary harvesters pick comparable amounts per day on a good berry patch.

Orthography in this paper follows the spellings in the Delgamuukw court case documents and Office of the Wet’suwet’en spellings. Witsuwit’en names accordingly differ from the more recent standard orthography. For example, Wet’suwet’en is now spelled Witsuwit’en, and digii ‘huckleberry’ is now spelled digï. There are also differences in some Gitksan spellings.

Areas in the valley bottoms of the major rivers, especially the Bulkley and the Kispiox were pre-empted by settlers and became private land. Indians were not eligible for pre-emption, though in a few exceptional cases Indians gained title to some parcels (Galois 1993–1994; Mills 2005). The village sites and a range of fishing sites of relatively small area were designated as Indian Reserves, and were thus “owned” by Indians collectively, though subject to the oversight and regulation of the Federal Government.

References

Alcorn, J. (1981). Huastec noncrop resource management: implications for prehistoric rain forest management. Human Ecology 9: 395–417.

Burton, P. (1998). Inferring the Response of Berry-Producing Shrubs to Different Light Environments in the ICHmc. Final Report on FRBC Project SB96030-RE. Prepared for the Science Council of BC. Symbios Research and Restoration, Smithers B.C.

Casey, E. (1996). How to get from space to place in a fairly short stretch of time, phenomenological prolegomena. In Feld, S., and Basso, K. H. (eds.), Senses of Place. School of American Research Advanced Seminar Series, Santa Fe, pp. 13–52.

Culhane, D. (1998). The Pleasure of the Crown, Anthropology, Law, and First Nations. Talonbooks, Burnaby, BC.

Daly, R. (1988). Anthropological Opinion on the Nature of the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en Economy. Opinion Evidence in Delgamuukw et al. v. The Queen in the light of the Province of British Columbia and the Attorney-General of Canada. British Columbia Supreme Court, 0343, Smithers Registry.

Daly, R. (2005). Our Box Was Full, an Ethnography for the Delgamuukw Plaintiffs. UBC, Vancouver.

Davidson-Hunt, I., and Berkes, F. (2003). Learning as You Journey: Anishinaabe Perception of Social-Ecological Environments and Adaptive Learning. Conservation Ecology 8(1) http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol8/iss1/.

Fox, J. L., Smith, C. A., and Schoen, J. W. (1989). Relation Between Mountain Goats and Their Habitat in Southeastern Alaska. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station General Technical Report PNW-GTR-246.

Galois, R. (1993–1994). The history of the Upper Skeena Region, 1850–1927. Native Studies Review 9(2): 113–183.

Gisday, Wa, and Delgam Uukw (1989) The Spirit in the Land The Opening Statement of the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en Chiefs in the Supreme Court of British Columbia, May 11 1987. Reflections, Gabriola.

Gottesfeld, L. M. J. (1993). Plants, Land and People, a Study of Wet’suwet’en Ethnobotany MA Thesis, Anthropology Department, University of Alberta.

Gottesfeld, L. M. J. (1994a). Wet’suwet’en ethnobotany. Journal of Ethnobiology 14: 185–210.

Gottesfeld, L. M. J. (1994b). Conservation, territory and traditional beliefs: an analysis of Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en subsistence, Northwest British Columbia, Canada. Human Ecology 22: 4443–465.

Gottesfeld, L. M. J. (1995). The role of plant foods in traditional Wet’suwet’en Nutrition. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 34: 149–169.

Gottesfeld, A. S., Rabnett, K. A., and Hall, P. E. (2002). Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and their Habitat. Skeena Fisheries, Hazelton.

Hargus, S. (1998). Witsuwit'en Topical Dictionary. Unpublished Report prepared for the Office of the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs. 206 p.

Hawkes, K., Hill, K., and O’Connell, J. F. (1982). Why hunters gather: optimal foraging and the Aché of eastern Paraguay. American Ethnologist 9: 379–398.

Hunn, E., and Meilleur, B. A. (1992). The utilitarian value and theoretical basis of folk biogeographical knowledge. Paper presented at the 3rd International Congress of Ethnobiology in Mexico City, November 10–14, 1992.

Hunn, E., and Meilleur, B. A. (1998). Toward a Theory of Ethnobiogeographical Classification. Paper presented at the American Anthropological Association conference in Philadelphia, December 1998.

Hunn, E. S., Selam, J., and Family (1990). Nch’i-Wána, “the Big River”, Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment, Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge, London and New York.

Johnson, L. M. (1997) Health, Wholeness, and the Land: Gitksan Traditional Plant Use and Healing. PhD Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta.

Johnson, L. M. (1998) Traditional Tenure among the Gitksan and Witsuwit’en: Its Relationship to Common Property, and Resource Allocation. http://www.indiana.edu/∼iascp/iascp98.htm

Johnson, L. M. (1999). Aboriginal burning for vegetation management in northwest British Columbia. In Boyd, R. (ed.), Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp. 238–254.

Johnson, L. M. (2000). “A place that’s good,” Gitksan landscape perception and ethnoecology. Human Ecology 28: 2301–325.

Johnson, L. M., and Hargus, S. (2007) Witsuwit’en Words for the Land—a Preliminary Examination of Witsuwit’en Ethnogeography. In Tuttle, S., Saxon, L., Gessner, S. and Berez, A. (eds). ANLC Working Papers in Athabaskan Linguistics Volume #6. Fairbanks, Alaska Native Language Center.

Johnson, L. M. (in press). Trail of story, traveller’s path-reflections on ethnoecology and landscape. Athabasca University Press, Edmonton

Johnson, L. M., and Hunn, E. Eds. (2008). Landscape Ethnoecology, Concepts of Physical and Biotic Space, Berghahn, New York (in press).

Johnson-Gottesfeld, L. M. and Hargus, S. (1998) Witsuwit’en Plant Classification and Nomenclature. Journal of Ethnobiology 18(1): 69–101.

Kuhnlein, H. and Turner, N.J. (1991). Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples, Nutrition, Botany and Use. Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology V. 8. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, Philadelphia, Reading, Paris, Montreaux, Tokyo and Melbourne.

Lepofsky, D., Hallet, D., Lertzman, K., Mathewes, R., McHalsie, A., and Washbrook, K. (2005). Documenting pre-contact plant management on the Northwest Coast, an example of prescribed burning in the Central and Upper Fraser Valley, British Columbia. In Deur, D., and Turner, N. J. (eds.), Keeping It Living, Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. University of Washington Press and Vancouver: UBC, Seattle, pp. 218–239.

Low, S. M., and Lawrence-Zúñiga, D.(eds) (2003). The Anthropology of Space and Place, Locating Culture. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA.

Mack, C. A. (2001). A burning issue—Native use of fire in Mount Rainier Forest Reserve. Paper presented at the Society of Ethnobiology 24th Annual Conference, Durango, Colorado March 7–10, 2001.

Mack, C. A., and McClure, R. H. (2002). Vaccinium processing in the Washington Cascades. Journal of Ethnobiology 22: 135–60.

McDonald, J. (2005). Cultivating in the Northwest, early accounts of Tsimshian horticulture. In Deur, D., and Turner, N. J. (eds.), Keeping It Living, Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. University of Washington Press and Vancouver: UBC, Seattle, pp. 240–271.

Mills, A. (1994). Eagle Down Is Our Law, Witsuwit’en Law, Feasts and Land Claims. UBC, Vancouver.

Mills, A. (Editor). (2005). Hang onto These Words, Johnny David’s Delgamuukw Evidence. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Minore, D. (1972) The Wild Huckleberries of Oregon and Washington—A Dwindling Resource. USDA Forest Service Research Paper-143, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station PNW-261.

Minore, D. (1975) Observations on the rhizomes and roots of Vaccinium membranaceum. USDA Forest Service Research Note PNW-261. Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experimental Station, Portland, Oregon. 5p.

Minore, D., Smart, A.W., and Dubraisch, M. E. (1979). Huckleberry ecology and management research in the Pacific Northwest. USDA Forest Service. General technical Report PNW-193.

Morrell, M. (1989) The struggle to integrate traditional Indian systems and state management in the salmon fisheries of the Skeena River, British Columbia. In Pinkerton, E. (Ed.) Cooperative Management of Local Fisheries, New Directions for Improved Management and Community Development. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, pp. 231–248.

Nadasdy, P. (2003) Hunters and Bureaucrats, Power, Knowledge, and Aboriginal-State Relations in the Southwest Yukon. UBC Press, Vancouver.

Nadasdy, P. (2005) The Anti-politics of TEK: The institutionalization of co-management discourse and practice. Anthropologica 47(2): 215–232.

Napoleon, V. (2005). Delgamuukw: a legal straightjacket for oral histories? Canadian Journal of Law and Society/Revue Canadienne Droit et Société 20: 2123–155.

Pendergast, B. A., and Boag, D. A. (1971). Nutritional aspects of the diet of spruce grouse in central Alberta. The Condor 73: 4437–443.

People of Ksan (1980). Gathering What the Great Nature Provided. Douglas and McIntyre, Vancouver.

Pollard, B. T. (2002). Mountain Goat Winter Range Mapping for the North Coast Forest District Report prepared for the North Coast Land and Resource Management Planning Team by Acer Resource Consulting Ltd., Terrace BC.

Ray, A. (1985) The Early Economic History of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en Territory. Unpublished report (revised 1987) on file at the Gitksan Treaty Office library, Hazelton, B. C. 57 p.

Ross, J. (1999). Proto-historical and historical Spokan prescribed burning and stewardship of resource areas. In Boyd, R. (Ed.), Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest, pp. 277–291.

Rundstrom, R. A. (1993). The role of ethics, mapping, and the meaning of place in relations between Indians and Whites in the United States. Cartographica 30: 121–28.

Rundstrom, R. A. (1995). GIS, indigenous peoples, and epistemological diversity. Cartography and Geographic Information Systems 22: 145–57.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State, How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Sterritt, N. J., Marsden, S., Galois, R., Grant, P. R., and Overstall, R. (1998). Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed. UBC, Vancouver.

Stewart, R. E. (1944). Food habits of blue grouse. The Condor 46: 3112–120.

Trusler, S. (2002). Footsteps Amongst the Berries: the Ecology and Fire History of Traditional Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en Huckleberry Sites. MSc. Thesis, Environmental Studies, University of Northern British Columbia. Tsing, A. L. 2005)

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction, An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

Turner, N. J. (1999). “Time to Burn”, traditional use of fire to enhance resource production by aboriginal peoples in British Columbia. In Boyd, R. (ed.), Indians, Fire and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp. 185–218.

Turner, N. J., and Peacock, S. (2005). Solving the perennial paradox, ethnobotanical evidence for plant resource management on the Northwest Coast. In Deur, D., and Turner, N. J. (eds.), Keeping It Living, Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. University of Washington Press and Vancouver: UBC, Seattle, pp. 101–150.

Turner, N. J., Gottesfeld, L. M. J., Kuhnlein, H. V., and Ceska, A. (1992). Edible Wood Fern Rootstocks of Western North America: Solving an Ethnobotanical Puzzle. Journal of Ethnobiology 12: 11–34.

Zwickel, F. C., Boag, D. A., and Brigham, J. H. (1974). The autumn diet of spruce grouse: a regional comparison. The Condor 76: 2212–214.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the elders and others from whom we learned about berries and berry patches, and our funders, especially the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Circumpolar Institute, the Athabasca Research Fund, the Jacobs Foundation, the Gitksan-Wet’suwet’en Education Society, the Kyah Wiget Education society (funding for Johnson), and the BC Ministry of Forests, Prince Rupert Forest Region and the Bulkley-Cassiar Forest District (funding for Trusler) as well as the Office of the Wet’suwet’en. We would particularly like to acknowledge the late Olive Ryan (Gwans), Gertie Watson (Gaxsbagaxs), the late Andy Clifton, the late Percy Sterritt, the late Art Mathews Sr, Kathleen Mathews, Art Mathews Jr.(Dinim Gyet), the late Ray Morgan, the late Dora Johnson (Gwamaats), Peter Muldoe (Gitluudahl), the late Pat Namox (Wah’tah’kwets), Lucy Namox (Goohlat), Rita George (Gilukhdun), Henry Alfred (Ut’akhgit), Alfred Joseph (Gisday Wa), Sam Wilson, the late Elsie Tait and our collaborators Darlene Vegh, Marilyn Freel, Ken Rabnett and Art Loring. We would also like to acknowledge the helpful comments of an anonymous reviewer in final preparation of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trusler, S., Johnson, L.M. “Berry Patch” As a Kind of Place—the Ethnoecology of Black Huckleberry in Northwestern Canada. Hum Ecol 36, 553–568 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-008-9176-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-008-9176-3