Abstract

Despite being a target of various policy interventions across developed countries, disparities in higher education participation among students from different socio-economic backgrounds remain persistent. While previous literature has outlined the processes through which parental resources can shape students’ educational decisions and pathways, the evidence remains scarce on how the effects of social origin on the participation in higher education vary along the academic performance distribution. Utilising multilevel models applied to large-scale linked administrative and survey data from Australia, this study explores how the participation in higher education varies along the students’ performance distribution by their social origins. Our results show that the effects of social origins on university participation are most pronounced in the middle of the academic performance distribution and taper off towards either end. Consideration is also given to exploring different ways to capture socio-economic status (SES) (i.e. through parental education and occupation) as an indicator of social origins. The results show that parental education serves as a better predictor of students’ university participation than does parental occupation. The paper discusses the implications of these findings for educational policies aimed at increasing university participation among individuals from low-SES backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Given the well-established role of higher education in facilitating positive socio-economic outcomes for individuals (e.g. Desjardins & Lee, 2016; Heckman et al., 2016; OECD, 2019), the issues surrounding inequality of educational opportunity (Boudon, 1974; Jackson, 2013b) and widening participation in higher education (e.g. Bradley et al., 2008) have received significant attention in research and social and educational policy in developed countries. However, across the OECD countries, children from low-SES families have been shown to be less likely to undertake university studies (e.g. Bourne et al., 2018; Czarnecki, 2018; Jackson, 2013a; Palmisano et al., 2022). The SES-induced gaps in academic performance have also been recognised as a barrier to participation and success in higher education in Australia (Productivity Commission, 2019)—the country of focus for this study—as well as internationally (OECD, 2019, 2023).

Attempting to explain these patterns, researchers have repeatedly pointed to the role of material resources, and social and cultural capital, as the key levers that high-SES parents can leverage to support their children in their educational pursuits (e.g. Bourdieu, 1986; Goldthorpe, 1996; Jackson, 2013a; Thompson, 2019). Low-SES parents may not have access to the same resources as more advantaged parents. These resources can play a crucial role in shaping various aspects of their children’s development, including cognitive and non-cognitive attributes. Additionally, they can impact academic performance, access to relevant information, and the presence of cultural norms and behaviours that shape aspirations, motivations, capabilities, and support structures. These factors collectively define the chances of their offspring accessing and succeeding in higher education (e.g. Björklund & Salvanes, 2011; Blossfeld, 2019, 2020; Bukodi et al., 2018).

While the association between SES and university participation is well documented, previous literature suggests an interplay between SES and academic ability, as evidenced by school performance or academic performance. For example, high-SES families can leverage their superior resources to compensate for their children’s low academic performance (e.g. through enrolling them in private schools or financing private tuition), which has been referred to as compensatory advantage (Bernardi, 2014; Bernardi & Cebolla-Boado, 2014; Heiskala et al., 2021). Despite these pointers, there is no solid understanding in the literature on how SES effects on university enrolment might vary along the academic performance distribution. It is important to understand this variation—if it does exist—to better target educational policies aimed at boosting university participation among low-SES students.

This paper adds robust evidence to the international literature on the SES effects on educational outcomes and contributes to the broader international literature on social mobility. Employing multilevel models to analyse large-scale linked survey and administrative data from the Australian state of Queensland, the paper offers insights into the role of SES effects, including their variation along the academic performance distribution, while also exploring different SES facets (approximating different types of resources that parents can mobilise). The findings are used to provide pointers for educational policies aimed at increasing university participation among individuals from low-SES backgrounds. Furthermore, the study adds to our understanding on how SES effects may depend on national policy contexts (e.g. Heiskala et al., 2021; Jackson, 2013a; Jæger & Holm, 2007) by presenting data from Australia, a country where the evidence on variations in university participation along the performance distribution by SES is scarce.

Previous literature explains the role of primary and secondary SES effects in shaping educational decisions and pathways (Boudon, 1974, see below). However, the evidence is much scarcer on how the SES effects might vary along the academic performance distribution. That is, is the size of the SES effect uniform along the academic performance distribution, or does it depend on where the student is placed on this distribution? This paper explores the variation in the SES effects, conditional on the position on the academic performance distribution, on university participation using a robust large-scale integrated data from Australia. It further discusses the findings against the backdrop of the previous theorising and the existing empirical evidence.

In addition to exploring the variation in the SES effects along the academic performance distribution, we also attempt to contribute to the discussions by tapping into the relative influence of families’ economic vis-a-vis social and cultural resources on their children’s university participation. We attempt to shed some light on this issue by comparing the influences of parental occupational status (as a proxy for economic resources) (Hauser, 2010; Hauser & Warren, 1997) and parental education (as a proxy for parental cultural resources), on their children’s university enrolment (see “Data and methods” section for further details).

In this paper, we recognise that the patterns of SES effects on university enrolment need to be investigated against the institutional and other context of the country being analysed (Heiskala et al., 2021; Palmisano et al., 2022). First, as Jackson (2013a) argue, the size of SES effects varies across different institutional contexts. Second, as Jæger and Holm (2007) point out, certain types of parental resources may play more salient roles in driving educational inequalities in some welfare regimes than in others. It is therefore important to understand the Australian institutional context.

In Australia, education is supported by both the Commonwealth (Federal) Government as well as the State Governments. The Commonwealth government supports university participation through interest-free fee support covering tuition costs, which is available to most domestic university students, and through various targeted funding schemes, including those dedicated to widening participation and promoting equity in higher education. Specifically, students from low-SES backgrounds have been supported by universities through the Higher Education Partnership and Participation Program (HEPPP). The program has funded activities that aim at increasing university participation of low-SES students (e.g. through scholarships, mentoring, and site visits/information to build aspirations) as well as supporting low-SES students to complete their degrees. The (primary and secondary) school system is the domain of the states, which provide access to education through government schools. These cater to the majority of students. In addition to government (public) schools, Catholic and independent schools also provide primary and secondary education.

Internationally, Australia is considered a country with a high standard of living and has demonstrated robust economic growth, as indicated by markers such as GDP per capita (OECD, 2021a). At the same time, Australia exhibits lower levels of income inequalities than many other highly-developed countries, such as the USA (OECD, 2021b). That said, people from low SES backgrounds have been persistently less likely to participate in university studies in Australia. Since official higher education data collections started to define SES status by socio-economic characteristics of the area in which students came from (‘first address’) in 2016, about 17% of enrolled university students have been from low SES backgrounds while they have constituted 25% of the population (Department of Education, 2023a).

Low SES students have also been consistently less likely to complete their studies. Longitudinal analyses by the Department of Education show that 69.0% of low SES domestic bachelor students who commenced studies in 2005 completed their studies within nine years while the equivalent percentages for medium and high SES students were 72.7% and 77.7% respectively. The nine-year completion percentage has declined since for all students, however, it has done so most severely for low SES students: for the 2014 commencing cohort the nine-year completions were down by down by 5.6 percentage points (to 63.4%) for low SES students, down by 4.1 percentage points (to 72.7%) for medium SES students, and down only by 2.3 percentage points (to 75.4%) for high SES students (Department of Education, 2023b).

The relevance of social background and academic ability for university participation

There is a wealth of evidence—in Australia and internationally—on the association between SES background and university studies (e.g. Bourne et al., 2018; Czarnecki, 2018; Jackson, 2013a; Palmisano et al., 2022). This is because socio-economic and cultural characteristics of families and the social and cultural resources available to them influence individual capabilities (including academic and non-cognitive skills), dispositions (e.g., views, attitudes and aspirations) and behaviours (e.g. post-school pathway and course selections). High-SES parents can deploy their material and non-material resources to help to shape their children’s educational opportunities, including university attendance (e.g. Bernardi, 2014; Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Jackson, 2013a; Thompson, 2019; Thompson & Simmons, 2013). Furthermore, the life-course trajectories of children from advantaged backgrounds are less affected by prior negative outcomes (including prior low academic performance) (Bernardi, 2014; Erola & Kilpi-Jakonen, 2017).

However, these SES effects may interact in complex ways with individual academic ability (as manifested as academic performance). The theoretical work on rational action theory (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Breen et al., 2014; Goldthorpe, 2014) provides insights into how parents’ motivation and decision-making processes may interplay with their children’s academic performance in shaping their educational choices. This theory is underpinned by rational-choice arguments whereby parents characteristically are driven to maximise the social and economic status of their children. Specifically, Breen and Goldthorpe (1997) posit that, when setting and pursuing educational and occupational goals for their children, average families are mostly driven by maintaining, at a minimum, the parental occupational status. Therefore, for the most part, high-SES families might tend to aim for maintaining the high status for their children, while lower-SES families might aim for, at a minimum, maintaining their current status for their children. Consequently, low-SES families are, on average, only willing to mobilise their sparse resources when the offspring offers high potential for success, for example, as signalled by high educational performance at school (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Holm et al., 2019).

Moreover, effectively maintained inequality theory (Lucas, 2001) posits that the advantaged groups will typically act to ensure advantages for themselves and their children, whenever seeking such advantages is possible. For instance, previous research shows that well-off and highly educated parents might employ compensatory strategies to counter the effect of low ability in their offspring (Bernardi, 2014; Esping-Andersen & Cimentada, 2018; Gil-Hernández, 2019) on average. Similarly, Grusky et al. (2019) observe that wealthy parents are mostly able to buy opportunity for their children in America and contend that policy reform should be put in place to constrain the rise of such ‘opportunity markets’ (p.19). Furthermore, empirical evidence across most of OECD countries shows that socio-economically advantaged families, on average, are more likely to use fee-paying out-of-school-time tutorials for their low-ability children than equally advantaged family with high-ability children, or than disadvantaged families with low-ability children (Huang, 2020).

Finally, drawing on a life course perspective, the compensatory advantage argument implies accumulation of advantage and disadvantage over time, and the ability to compensate disadvantage in one area (e.g. academic ability) with advantages in other areas (e.g. material resources). As Bernardi (2014, p. 75) states, “[a]n early disadvantage is likely to persist or grow larger over time for people from disadvantaged families, whereas it is likely to attenuate for those from more advantaged families. In other words, the compensatory advantage mechanism predicts that patterns of cumulative disadvantage and unfavourable path dependence are less prevalent among upper-class students.” As such, high-SES parents are still able, through application of their economic, social, and/or cultural resources, to reverse the effects of their children’s earlier poor academic performance later in life.

The interplay between SES and academic performance: the relevance of primary and secondary SES effects

While a considerable body of research influenced by Bourdieu’s theory (1986) highlights the crucial role of different family resources, Boudon (1974) outlines the processes through which such disparities in parental resources impact upon their offspring’s educational opportunities. Specifically, Boudon (1974) postulates that socio-economic background affects educational opportunity in two ways: first, through a primary effect, referring to the impact of social origin on academic performance; and through a secondary effect, which is defined as the impact of social origin on educational attainmentFootnote 1 after controlling for academic performance (see Bukodi et al. (2021) for the evolvement of these concepts, also Jackson, (2013a) and Thompson (2019) for more detailed discussion). The issue of secondary SES effects is relevant, as it goes to the core of considerations surrounding fairness in society, including meritocratic principles and equality of opportunities (Civil & Himsworth, 2020; Jackson, 2013a)—including equal opportunity to attend university among people with the same levels of academic ability. Secondary SES effects have direct relevance for economic development of societies, through their role in hindering the development of human capital at the individual level, and the economic costs of ‘wasted talent’ (Bukodi et al., 2017; Sikora & Saha, 2011), where academically strong low-SES individuals might not realise their full potential.

Recent decades have witnessed a significant development of Boudon’s (1974) process theory of inequalities in educational opportunity (Erikson, 2019; Erikson et al., 2005; Jackson et al., 2007; Thompson, 2018). Scholars including Erikson et al. (2005) and Jackson et al. (2007) developed mathematical approach to explicitly demonstrate the separation between the primary and secondary SES effects. Jackson and her collaborators further utilised this approach to explore the relative importance of primary and secondary effects across eight developed countries (i.e. Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Italy, Sweden, England, and the USA). That body of work posits that social stratification of educational attainment is driven by the combination of academic performance, constraints upon choices, and institutional differences across countries (Jackson, 2013b). The notion of secondary SES effects is also echoed in the conceptualisations of what is considered the direct effect of social origin on labour market outcomes among university graduates, over and above respondents’ tertiary education attainment (Bernardi & Gil-Hernández, 2021). Studying patterns of university enrolment are thus only part of a much bigger picture of how SES advantage and disadvantage operates along the educational life course.

The distinction between primary and secondary SES effects (Boudon, 1974) provides a theoretical foundation from which different underlying mechanisms can be identified and as such, potential policy interventions can be designed accordingly (Jackson, 2013a). Specifically, it is important to establish whether the inequality in educational outcomes, such as university participation, is mainly driven by primary or secondary effects. For instance, if the socio-economic gap in school performance is increasing in a country, this is consistent with the primary SES effects and may require more focus on early education; however, if high achievers from low-SES background are consistently less likely to enrol in university, then a policy targeting secondary effects might be more effective to address the issue. It is also important to understand the interplay between primary and secondary effects of SES. As Jackson et al., (2007, p. 225) points out, “the possibility must be recognised that any gains that may be made in reducing primary effects via interventions in early years—at a probably high cost – will be at least in some degree offset in so far as the further problem of secondary effects is not addressed.” This study contributes to our understanding of the interplay of primary and secondary effects by studying how the SES effects on university participation depends on the individual’s academic performance.

Data and methods

The data used in this study comes from the state of Queensland, the third-largest state in Australia, with a total population of around 5.2 million (ABS (Australian Beurau of Statistics), 2022). The proportion of Queensland school leavers going to university was 41.2%, those taking up the VET option around 21.9%, followed by about 26.9% in employment and 2.6% NEET in 2021 (Department of Education, 2021). These educational statistics, as well as the overall population characteristics of Queensland, are broadly representative of those for Australia.

The study uses unique large-scale linked administrative and survey data provided by the Queensland Department of Education, covering students attending public schools in Queensland. Administrative records for a full cohort of students enrolled in year 9 in 2014 in any government school in the state were linked to a survey capturing their initial post-school destinations at around six months after graduating from year 12 (the ‘Next Step’ survey). The survey is conducted approximately six months after the end of the school year, timed to occur after tertiary education offers for the year have been accepted, and captures destinations for more than 80% of students completing school in Queensland (Department of Education, 2018). The analytic sample includes 21,772 students enrolled in year 9 in 2014 in Queensland government schools who completed year 12 and participated in the Next Steps survey in 2018.

Measuring SES

Socio-economic status is a multifaceted construct, extending beyond tangible resources, and while frequently invoked in educational research and policy discourse, the measurement of SES lacks universal consensus. Previous research shows that different types of family resources (i.e. parental income, education, and social status) have separate effects on individuals’ educational and socioeconomic outcomes and that they work in different ways (e.g. Blossfeld, 2019, 2020; Bukodi & Goldthorpe, 2013; Bukodi et al., 2018; Erikson, 2016, 2019). For example, Bukodi and Goldthorpe (2013) employed data from three cohorts, born in the UK in 1946, 1958, and 1970, to explore the effects of parents’ class, education, and status on their offspring’s qualification attainment. They found that each of the three factors has effects that are independent of the others. In a similar vein, Erikson (2016) also found that parental education, class, status, and income have independent effects on their children’s educational attainment in Sweden. Methodological choices in operationalizing SES vary across studies, often constrained by data availability, particularly when utilising secondary data sources (Zajac & Tomaszewski, 2023).

Given the above, the present study focuses on two indicators of family resources to capture SES: parental education and occupation. Parental education has been shown to have a greater association with children’s educational attainment than other indicators do (e.g. Blossfeld, 2019; Bukodi et al., 2021; Erikson, 2019; Erola et al., 2016). This is because it serves as an important indicator of parental social and cultural resources, which can manifest themselves as primary and secondary SES effects on educational outcomes. Students with highly educated parents can gain exposure to more stimulating cultural, intellectual, and learning-focused environments at home, which can influence school performance (primary effect) as well as aspirations and decision-making (secondary effect) (Aschaffenburg & Maas, 1997; Bukodi & Goldthorpe, 2013; Gunn, 2005).

On the other hand, parental occupational status is a proxy for economic resources and occupational aspirations (Buis, 2013; Hauser, 2010; Hauser & Warren, 1997). Economic resources may in a number of ways play a significant role in shaping the chances of accessing university: they structure opportunities and constraints for procuring learning-relevant resources (e.g. learning spaces, technology, internet access and speed, and private tutoring) and enable students to focus on learning by minimising their need to work or care for others (Björklund & Salvanes, 2011; Blanden & Gregg, 2004; Erola et al., 2016). Economic resources can also affect perceptions of risks, costs, and benefits that shape aspirations and decision-making processes (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Goldthorpe, 1996).

In addition to testing the separate effects of parental education and occupation, we employ a combined indicator as an overarching measure of SES. Due to the absence of a universal approach to amalgamating parental education and occupation into a single SES indicator, we tested several methods utilised in recent Australian studies of educational outcomes, all of which produced substantively consistent results.Footnote 2 The results reported in the paper follow the approach by Houng and Justman (2014), which sets out rules for combining parental education and occupation, while taking into account the family composition (e.g. single-parent or two-parent family). Parental occupation and education is captured in school administrative systems according to nationally standardised format designed by the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA).Footnote 3 Applied to the data at hand, the approach resulted in the following SES categories:

-

Low SES (~ 22% of students in the sample): both parents’ education and occupation categories are in the lower range, e.g. one parent works in a non-managerial/a professional role while the other is unemployed; neither parent has completed high school.

-

Low-mid SES (~ 32% of students in the sample): both parents’ education and occupation categories are mid to low range, e.g. both parents work in a non-managerial/a professional role; neither parent has completed high school.

-

Mid-high (~ 25% of students in the sample): both parents’ education and occupation categories are mid‐range or one is high and one is low, e.g. both parents work in a non-managerial/a professional role; at least one parent has completed high school (or an equivalent diploma).

-

High SES (~ 21% of students in the sample): both parents’ education and occupation categories are high or one parent’s is high and the other one mid‐range, e.g. at least one parent works in a managerial or professional occupation; at least one parent has a bachelor degree or higher.

School performance

School performance is captured through students’ achievement in a standardized national assessment test, the National Assessment Program–Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), using scores for numeracy and reading. NAPLAN scores are represented on a continuous scale with a theoretical range 0–1000. For the purpose of this paper, we used the mean of the standardised numeracy and reading scores at year 9 as the indicator of academic performance.Footnote 4 Sensitivity analyses using quantiles of the mean of the standardised numeracy and reading scores were also carried out, and the results are presented in the Appendix.

Analytic approach

The study employs multilevel logistic regression models with individuals nested within schools, with the main model formulated as follows:

where Uni denotes a binary measure indicating university studies as the post-school destination (vs. another destination) of an individual i completing year 12 at school j; C is a vector of control variables; SES is a categorical measure for SES; A represents academic performance as captured by year 9 NAPLAN scores; \({u}_{j}\) is school effect; e is a stochastic error; and the βs are coefficients or vectors of coefficients of interest to be estimated. Socio-economic background and academic performance are interacted in the model (reflected by the term SES * A).

The analyses proceed through several steps. Firstly, we examine differences in the likelihood of attending university for students with different performance levels and of different socio-economic backgrounds (as captured by the SES categories on our composite measure). Of particular interest are the interaction effects (β4) between socio-economic background and performance, as these shed light on the variation in the effects of SES on university participation along the school performance distribution.

Secondly, we run additional analyses covering alternative definitions of SES—using parental occupation and education. Specifically, in these analyses, we replace the SES measure with two indicators—one indicating parental university degree and one indicating high parental occupational status. We interact both indicators with school performance when estimating the likelihood of university participation.

All models control for a number of individual-level characteristics, including student age, gender, Indigenous status, language background, health and disability markers, as well as a range of school-level controls, including school size, school SES,Footnote 5 school proportion of Indigenous students, and school location/remoteness. Appendix Table 1 in the Appendix presents the descriptive statistics for the analytic sample, including the outcome variable, key predictors, and control variables.

Results

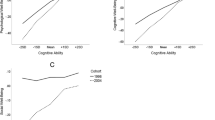

We first examine the (secondary) SES effects on university participation by controlling for the students’ prior performance levels. We present full model results in Appendix Table 2 in the Appendix. The results show that, in comparison to their peers from high-SES families, students from all three lower categories are less likely to enrol in university (OR = 0.47 for low SES, p < 0.001; OR = 0.54 for low-mid SES, p < 0.001; OR = 0.65 for mid-high SES, p < 0.001). To better demonstrate the SES variations in the likelihood of university participation along students’ academic performance level, we illustrate the interactions between students’ SES background and academic performance in a graphical format, by plotting the predicted probabilities of attending university for different SES categories. Figure 1 plots the SES effects on university participation depending on the level of academic performance, captured by standardised year 9 NAPLAN scores.Footnote 6

The results show that there is an SES gradient on university participation, with students from higher SES backgrounds more (or at least, equally) likely to enrol into university, regardless of their academic performance levels. Secondly, the SES effects are particularly pronounced when contrasting high-SES students and the other three SES categories, while the differences between those other three categories are relatively small and often not statistically significant. In other words, it is the high-SES students who stand out from the others (in terms of their advantage), rather than the low-SES ones (in terms of their disadvantage). Thirdly, the SES disparities appear to vary along the NAPLAN distribution—with the differences being largest towards the middle of the academic performance distribution. The pattern is also confirmed by the sensitivity analyses that use quantiles of the standardised scores to measure academic performance (Fig. 4 in the Appendix).

To examine more closely the shape of the SES effects on university participation along the academic performance distribution, Fig. 2 focuses explicitly on the differential between the high- and low-SES categories. The high-SES ‘premium’ is most pronounced in the middle of the academic performance distribution and tapers off towards either end—more visibly so towards the high end. This is an important finding from a policy perspective as it identifies the group of individuals (in the middle of the academic performance distribution) for which there might be the most potential for policies to reduce the SES gaps in university enrolment.

To explore the question whether parental education or occupation may be more relevant in accounting for the SES effects on university participation, we replace our combined SES measure with two separate indicators: one capturing parental university degree and another indicating high parental occupational status. We present full results in Appendix Table 3, which show that students with parents having a degree are more likely to enrol in university (OR = 1.75, p < 0.001) than the rest of the sample, and those whose parents working in a high-status occupation are also more likely to do so (OR = 1.22, p < 0.001). Again, to better illustrate the comparison, we present the results in a graphical form to aid the interpretation (Fig. 3). The figure shows the difference in the probability of attending university between school leavers whose parents have a degree vs. those who do not, and the difference between school leavers whose parents are in high-status occupations vs. students with parents who are not. The results suggest that a parental degree is more influential in driving the SES effects on university participation than a parental high-status occupation. The SES effect emanating from a parental degree is larger at all student performance levels (although not always significantly so).

Discussion and conclusions

This paper contributes to the academic literature on the effects of socio-economic background on the likelihood of university participation by focusing on what has been coined as secondary effects of SES, and their variation along the school performance distribution. Secondary effects reflect the influences of socio-economic background that go beyond the influences through academic performance, that is, they capture the ‘net’ effects of SES while controlling for students’ academic performance. Understanding the secondary effects of SES is important from a policy perspective as any investments in early interventions to reduce the gap in academic performance will be largely unrealised if high academic achievers from low-SES family backgrounds were to still miss out on higher education.

Leveraging robust large-scale linked administrative and survey data from Queensland, the third-largest state in Australia, the analyses presented in this paper reveal several important findings. First, we show that SES effects—measured as a combination of parental education and occupational status—on the likelihood of university enrolment are still evident despite controlling for students’ academic performance in secondary school. Second, we demonstrate that the SES effects, when controlling for academic performance, are not equally distributed, but instead follow an inverted u-shape distribution along the academic performance. Specifically, the SES differences are most pronounced for students around the middle of the academic performance distribution—it is for these students that, in relative terms, high-SES background most significantly increases the likelihood of university enrolment following the completion of secondary school.

The latter finding is particularly relevant from a policy perspective as it might help to identify a significant group of students (those in the middle of school performance distribution), where interventions aimed at reducing the impacts of socio-economic background might be most effective. The finding may also explain why some previous Australian studies found the SES differences on university participation largely disappeared when adjusted for the tertiary ranking scores (Cardak & Ryan, 2009). In Australia, Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) is commonly used in university applications. Preparation for ATAR requires students and parents to strategically choose subjects from year 10 and the students need to put into consistent efforts through years 11 and 12 to maximise their ATAR scores (Shergold et al., 2020). As such, the group of students highlighted in our findings—those low-SES students around the middle of the academic performance distribution—might be more likely to pursue non-ATAR paths. This highlights the importance of providing students with quality information on the subject choices in upper secondary school that will maximise their chances of applying for university, including the acquisition and the quality of their tertiary ranking scores (Bennett et al., 2022).

By contrast with those in the middle of the academic performance distribution, for both low and high performers, the SES effects on university participation are much smaller—in particular, high performers nearly universally enrol into university after leaving school. While low performers largely miss out on university regardless of their background, high-SES students are still significantly more like to go to university than low-SES students at the low end of academic performance in year 9. These findings echo the patterns found in broader sociological literature, such as on ‘glass floor effect’ (Gugushvili et al., 2017; McKnight, 2015; Reeves & Howard, 2013) and ‘compensatory advantage model’ (Bernardi, 2014; Bernardi & Ballarino, 2016; Bernardi & Cebolla-Boado, 2014).

While other studies found that high-SES students at the top end of the academic performance distribution may benefit from ‘multiplicative advantage’ (Bernardi & Ballarino, 2016; Heiskala et al., 2021), we do not see such pattern in our data, where there are virtually no SES differences among high performers. For low-SES high performers, this can be explained by the fact that low-SES families might be more willing to mobilise their scarce resources due to the potential for academic success as signalled by high educational performance at school (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Holm et al., 2019). Furthermore, various equity initiatives operating in the higher education space in Australia, including interest-free tuition loans, and merit- and needs-based scholarships offered by many universities, would provide entry pathways for high-achieving low-SES students. Nevertheless, consistent with the effectively maintained inequality theory (Lucas, 2001), we might expect that the SES advantage could still manifest itself through the differences in the prestige of a university or degree attended, despite similar university enrolment rates among top performers from both low- and high-SES backgrounds.

Further, we show that parental educational attainment is a stronger predictor of SES-induced differences in university enrolment compared with parental occupational status. The dominance of parental educational qualifications over their occupational status when predicting their offspring’s educational outcomes is a relatively well-established finding in the literature (Blossfeld, 2019; Buis, 2013; Bukodi & Goldthorpe, 2013; Bukodi et al., 2021). However, we show that this pattern also holds when studying secondary effects of SES, that is, parental education plays a more prominent role compared to parental occupation, even when controlling for the offspring’s academic performance. Since parental occupation might be a better proxy for household income, compared with parental education, these findings align with previous research from Australia. For example, Cardak and Ryan (2022) show that household income, or the ability to pay, does not appear to play a major role for the chances of university participation when academic performance is controlled for. This also aligns with the features of the Austrian higher education system, including the availability of income-contingent loans that enable students to defer fees, as well as relatively high levels of paid employment among students. Based on these features, we would expect that parental education might be more relevant for children’s university participation, compared with parental occupation or income. Furthermore, the dominant role of parental education suggests that highly educated parents might be particularly driven to steer their high-achieving children towards higher education, a finding that fits with the rational choice theory arguments (e.g. Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997).

While contributing to the literature with a range of novel findings, the present study is not without limitations. First, we measure academic performance in year 9, which although it is the most senior year for students to sit the NAPLAN tests, is still a few years away from the school completion. Future studies could attempt to measure performance in even later years—for example, through using teachers’ assessment grades. Furthermore, our outcome variable—university enrolment—is captured early after leaving school, at about six months post-completion. Future studies should consider longer-term outcomes, including university retention and completion, and labour market outcomes. Finally, our sample was constrained to the government school students in the state of Queensland. While we expect these findings to be broadly representative of Australia, replicating the analyses using national and international data would further add to the robustness of the results reported here.

All in all, the study adds to the evidence on the relevance of socio-economic background—and in particular, parental education—for shaping individuals’ likelihood of university participation. Furthermore, our findings show that SES matters for university participation among students at the same levels of academic performance. Extant literature shows that improving high school performance has been identified as an important channel through which university participation among disadvantaged students may be improved (Cardak & Ryan, 2022). However, our results suggest that academic ability does not explain out all the SES differences: the SES effects are still evident despite controlling for academic performance in the models. Therefore, other factors must also be at play, such as the differences in access to relevant information, differences in educational and occupational aspirations, or perceptions of relative costs and benefits of higher education. Furthermore, the material barriers that may be present—and may disproportionally affect low SES students—through a combination of tuition fees, the costs associated with potential relocation, accommodation, and sustenance are also important to consider. Educational policies should aim to break down these multiple barriers, by providing students not only with material support, such as scholarships, bursaries, or subsidised accommodation, but also with non-material support, including academic preparedness developed at school, the provision of quality career guidance, and the provision of relevant information about a full range of post-secondary options. For instance, previous research (e.g. Tomaszewski et al., 2017) suggests that quality career guidance can be particularly beneficial to low-SES students. The present study further points to a specific sub-group where such interventions might be particularly efficient at reducing the SES differences—the students around the middle of academic performance distribution. It is these students who often ‘sit on the fence’ undecided whether to take a university or vocational or employment path, and where well-designed interventions can help them to make an informed choice that will lead to the best outcome for them, and for the society as a whole.

Appendix

Data Availability

The study used customised linked administrative and survey data provided by the Queensland Department of Education. Access to the data is at the discretion of the Queensland Department of Education and was provided to the research team for the purpose of the project. The authors do not retain a copy of the data.

Notes

Alternative SES specifications used in sensitivity analyses included following Tomaszewski et al. (2022a) with three SES categories (low: ~ 33% of the sample; medium: ~ 37% of the sample; and high: ~ 30% of the sample), and Tomaszewski et al. (2022b) with four categories (jobless households: ~ 7% of the sample; low SES: ~ 9% of the sample; mid-SES: ~ 56% of the sample; high SES: ~ 28% of the sample). All SES specifications tested produced substantively equivalent results.

Parental education and occupation in the administrative data was captured on student enrolment forms in the August, 2014, enrolment snapshot. Instructions on how schools should capture student and parental data that include pre-structured forms are provided by ACARA. These include pre-defined categories for parental school and non-school qualifications that parents are asked to tick, and occupational groupings that are listed and from which parents are asked to select the one that reflects their main job (ACARA (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority), 2022). The educational categories and occupational groupings defined by ACARA have been used to generate socio-economic scores for schools for the purpose of funding processes and when comparing student performance across schools.

Where numeracy and reading scores were missing, they were imputed. Imputations were based on regression modelling using student, parent, and school characteristics as well as Year 7 NAPLAN scores for numeracy and reading, respectively. Prior to this modelling, we imputed missing Year 7 NAPLAN scores based on modelling NAPLAN scores using student, parent, and school characteristics. Year 7 and Year 9 NAPLAN scores were strongly correlated, which is why Year 7 NAPLAN scores were used in estimating Year 9 NAPLAN scores.

School SES was captured through the Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA), which is computed for each school in Australia. Please see guide-to-understanding-icsea-values.pdf (myschool.edu.au) for more details.

The range of standardised NAPLAN scores in these figures has been truncated to a range of − 1.9 to 2.4 to exclude cases with extreme NAPLAN values from the graph. Excluded cases account for 2% of the sample. Figure 4 in the Appendix shows the results from a model using an alternative specification with 20 NAPLAN quantiles.

References

ABS (Australian Beurau of Statistics). (2022). Snapshot of Queensland. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/snapshot-qld-2021

ACARA (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority). (2022). Data standards manual: student background characteristics. ACARA: Sydney. https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/data-standards-manual-student-background-characteristics

Aschaffenburg, K., & Maas, I. (1997). Cultural and educational careers: The dynamics of social reproduction. American Sociological Review, 62(4), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657427

Bennett, D., Coffey, J., Bawa, S., Carney, D., Dockery, A. M., Franklyn, K., Koshy, P., Li, I. W., Parida, S., & Unwin, S. (2022). Ameliorating disadvantage: Creating accessible, effective, and equitable careers and study information for low socioeconomic students: Final report. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education.

Bernardi, F. (2014). Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality: A regression discontinuity based on month of birth. Sociology of Education, 87(2), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040714524258

Bernardi, F., & Ballarino, G. (2016). The intergenerational transmission of inequality and education in fourteen countries: A comparison. In F. Bernardi & G. Ballarino (Eds.), Education, Occupation and Social Origin: A Comparative Analysis of the Transmission of Socio-Economic Inequalities (pp. 255–283). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bernardi, F., & Cebolla-Boado, H. (2014). Previous school results and social background: Compensation and imperfect information in educational transitions. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct029

Bernardi, F., & Gil-Hernández, C. J. (2021). The social-origins gap in labour market outcomes: Compensatory and boosting advantages using a micro-class approach. European Sociological Review, 37(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa034

Björklund, A., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Education and family background: Mechanisms and policies. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education (Vol. 3, pp. 201–247). Elsevier.

Blanden, J., & Gregg, P. (2004). Family income and educational attainment: A review of approaches and evidence for Britain. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 20(2), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grh014

Blossfeld, P. N. (2020). The role of the changing social background composition for changes in inequality of educational opportunity: An analysis of the process of educational expansion in Germany 1950–2010. Advances in Life Course Research, 100338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100338

Blossfeld, P. N. (2019). A multidimensional measure of social origin: Theoretical perspectives, operationalization and empirical application in the field of educational inequality research. Quality & Quantity, 53(3), 1347–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0818-2

Boudon, R. (1974). Education. Wiley.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

Bourne, M., Bukodi, E., Betthäuser, B., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2018). ‘Persistence of the social’: The role of cognitive ability in mediating the effects of social origins on educational attainment in Britain. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 58, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2018.09.001

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian Higher Education. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/104346397009003002

Breen, R., van de Werfhorst, H. G., & Jæger, M. M. (2014). Deciding under doubt: A theory of risk aversion, time discounting preferences, and educational decision-making. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu039

Buis, M. L. (2013). The composition of family background: The influence of the economic and cultural resources of both parents on the offspring’s educational attainment in the Netherlands between 1939 and 1991. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 593–602.

Bukodi, E., Bourne, M., & Betthäuser, B. (2017). Wastage of talent?: Social origins, cognitive ability and educational attainment in Britain. Advances in Life Course Research, 34, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2017.09.003

Bukodi, E., Eibl, F., Buchholz, S., Marzadro, S., Minello, A., Wahler, S., Blossfeld, H.-P., Erikson, R., & Schizzerotto, A. (2018). Linking the macro to the micro: A multidimensional approach to educational inequalities in four European countries. European Societies, 20(1), 26–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2017.1329934

Bukodi, E., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2013). Decomposing ‘social origins’: The effects of parents’ class, status, and education on the educational attainment of their children. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 1024–1039.

Bukodi, E., Goldthorpe, J. H., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Primary and secondary effects of social origins on educational attainment: New findings for England. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(3), 627–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12845

Cardak, B., & Ryan, C. (2022). Socioeconomic disadvantage, ability to pay and university attendance in Australia. Education economics, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2022.2085668

Cardak, B., & Ryan, C. (2009). Participation in higher education in Australia: Equity and access. Economic Record, 85(271), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2009.00570.x

Civil, D., & Himsworth, J. J. (2020). Introduction: Meritocracy in perspective. The rise of the meritocracy 60 years on. The Political Quarterly, 91(2), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12839

Czarnecki, K. (2018). Less inequality through universal access? Socioeconomic background of tertiary entrants in Australia after the expansion of university participation. Higher Education, 76(3), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0222-1

Department of Education. (2018). Undergraduate applications, offers and acceptances 2018 Queensland Government, Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2021). Next Step Profiles: Post-school destinations of Year 12 completers. Queensland Government, Department of Education.

Department of Education. (2023b). Completion rates – cohort analyses. Table 1: Cohort analyses (%) for Table A and B institution commencing bachelor students over a nine-year period, 2005 to 2014 commencing cohorts. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/completion-rates-higher-education-students-cohort-analysis-20052022

Department of Education. (2023a). Selected higher education statistics – 2022 student data. Section 16 – equity performance data. Table 16.4: Equity – particpation rates for domestic students at Table A and B institutions, 2009 to 2022. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2022-section-16-equity-performance-data

Desjardins, R., & Lee, J. (2016). Earnings and employment benefits of adult higher education in comparative perspective: evidence based on the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC). UCLA. https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt0jz0k1pp/qt0jz0k1pp.pdf

Erikson, R. (2016). Is it enough to be bright? Parental background, cognitive ability and educational attainment. European Societies, 18(2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1141306

Erikson, R. (2019). How does education depend on social origin? In R. Becker (Ed.), Research Handbook on the Sociology of Education (pp. 35–56). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Erikson, R., Goldthorpe, J. H., Jackson, M., Yaish, M., & Cox, D. R. (2005). On class differentials in educational attainment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(27), 9730–9733. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0502433102

Erola, J., Jalonen, S., & Lehti, H. (2016). Parental education, class and income over early life course and children’s achievement. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 44, 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.01.003

Erola, J., & Kilpi-Jakonen, E. (2017). Compensation and other forms of accumulation in intergenerational social inequality. In J. Erola & E. Kilpi-Jakonen (Eds.), Social Inequality across the Generations: The Role of Compensation and Multiplication in Resource Accumulation (pp. 3–24). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Cimentada, J. (2018). Ability and mobility: The relative influence of skills and social origin on social mobility. Social Science Research, 75, 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.06.003

Gil-Hernández, C. J. (2019). Do well-off families compensate for low cognitive ability? Evidence on social inequality in early schooling from a twin study. Sociology of Education, 92(2), 150–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040719830698

Goldthorpe, J. H. (1996). Class analysis and the reorientation of class theory: The case of persisting differentials in educational attainment. British Journal of Sociology, 47(3), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/591365

Goldthorpe, J. H. (2014). The role of education in intergenerational social mobility: Problems from empirical research in sociology and some theoretical pointers from economics. Rationality and Society, 26(3), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463113519068

Grusky, D. B., Hall, P. A., & Markus, H. R. (2019). The rise of opportunity markets: How did it happen & what can we do? Daedalus, 148(3), 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_01749

Gugushvili, A., Bukodi, E., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2017). The direct effect of social origins on social mobility chances: ‘Glass floors’ and ‘glass ceilings’ in Britain. European Sociological Review, 33(2), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx043

Gunn, S. (2005). Translating Bourdieu: Cultural capital and the English middle class in historical perspective. British Journal of Sociology, 56(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00046.x

Hauser, R. M. (2010). Intergenerational economic mobility in the United States-Measures, differentials, and trends. EurAmerica, 40(3), 635–681.

Hauser, R. M., & Warren, J. R. (1997). Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. Sociological Methodology, 27(1), 177–298.

Heckman, J. J., Humphries, J. E., & Veramendi, G. (2016). Returns to education: The causal effects of education on earnings, health and smoking. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heiskala, L., Erola, J., & Kilpi-Jakonen, E. (2021). Compensatory and multiplicative advantages: Social origin, school performance, and stratified higher education enrolment in Finland. European Sociological Review, 37(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa046

Holm, A., Hjorth-Trolle, A., & Jæger, M. M. (2019). Signals, educational decision-making, and inequality. European Sociological Review, 35(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz010

Houng, B., & Justman, M. (2014). NAPLAN Scores as Predictors of Access to Higher Education in Victoria. The University of Melbourne.

Huang, M.-H. (2020). Compensatory advantage and the use of out-of-school-time tutorials: A cross-national study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 100472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100472

Jackson, M. (Ed.). (2013a). Determined to Succeed? Performance versus Choice in Educational Attainment. Stanford University Press.

Jackson, M. (2013b). Introduction: How is inequality of educational opportunity generated? The case for primary and secondary effects. In M. Jackson (Ed.), Determined to Succeed? Performance versus Choice in Educational Attainment (pp. 1–33). Stanford University Press.

Jackson, M., Erikson, R., Goldthorpe, J. H., & Yaish, M. (2007). Primary and secondary effects in class differentials in educational attainment: The transition to A-level courses in England and Wales. Acta Sociologica, 50(3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699307080926

Jæger, M. M., & Holm, A. (2007). Does parents’ economic, cultural, and social capital explain the social class effect on educational attainment in the Scandinavian mobility regime? Social Science Research, 36(2), 719–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.11.003

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690. https://doi.org/10.1086/321300

McKnight, A. (2015). Downward mobility, opportunity hoarding and the ‘glass floor’. Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission.

OECD. (2019). Balancing School Choice and Equity: An International Perspective Based on PISA. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/19963777

OECD. (2021b). Income inequality (indicator) https://doi.org/10.1787/459aa7f1-en

OECD. (2021a). Gross domestic product (GDP) (indicator) https://doi.org/10.1787/dc2f7aec-en

OECD. (2023). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en

Palmisano, F., Biagi, F., & Peragine, V. (2022). Inequality of opportunity in tertiary education: Evidence from Europe. Research in Higher Education, 63(3), 514–565.

Productivity Commission. (2019). The Demand Driven University System: A Mixed Report Card. The Productivity Commission.

Reeves, R. V., & Howard, K. (2013). The glass floor: Education, downward mobility, and opportunity hoarding. Center on children and families at Brookings.

Shergold, A. C., Calma, T., Russo, S., Walton, P., Westacott, J., Zoellner, D., & O’Reilly, P. (2020). Looking into the future. Report of the review of senior secondary pathways into work, further education and training. Education Council Australia.

Sikora, J., & Saha, L. J. (2011). Lost talent? The occupational ambitions and attainments of young Australians. The National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER).

Thompson, R. (2019). Education, inequality and social class: Expansion and stratification in educational opportunity. Routledge.

Thompson, R. (2018). Performance, choice and social class: Theorising inequalities in educational opportunity. In R. Simmons & J. Smyth (Eds.), Education and Working-Class Youth (pp. 79–103). Palgrave Macmillan.

Thompson, R., & Simmons, R. (2013). Social mobility and post-compulsory education: Revisiting Boudon’s model of social opportunity. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(5–6), 744–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.816038

Tomaszewski, W., Ablaza, C., Straney, L., Taylor, C., Millar, J., & Schlapbach, L. (2022a). Educational outcomes of childhood survivors of critical illness—A population-based linkage study. Critical Care Medicine, 50(6), 901–912. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005461

Tomaszewski, W., Perales, F., & Xiang, N. (2017). Career guidance, school experiences and the University participation of young people from low socio-economic backgrounds. International Journal of Educational Research, 85C, 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.06.003

Tomaszewski, W., Zajac, T., Rudling, E., te Riele, K., McDaid, L., & Western, M. (2022b). Uneven impacts of COVID -19 on the attendance rates of secondary school students from different socioeconomic backgrounds in Australia: A quasi-experimental analysis of administrative data. Australian Journal of Social Issues. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.219

Zajac, T. & Tomaszewski, W. (2023) The relative influence of different markers of socio-economic status on university participation: evidence from the Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) data, In: Australia’s welfare 2023. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Acknowledgements

Data come from linked administrative and survey data provided by the Queensland Department of Education. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions by Cain Polidano, Chris Ryan, and Buly Cardak to the work on the project that provided the basis for the paper, and to thank them for their comments on the early drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This research was funded by the Queensland Department of Education through the Education Horizon research grant scheme. Any claims made in this article represent the authors’ views, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department. The research was also supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (grant number: CE200100025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomaszewski, W., Xiang, N. & Kubler, M. Socio-economic status, school performance, and university participation: evidence from linked administrative and survey data from Australia. High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01245-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01245-7