Abstract

Despite challenging and uncertain circumstances and the perception of being tokenized symbols in Japanese universities, the majority of international academics are more inclined to remain in their affiliations. The study intends to elucidate how international academics make sense of their decision to remain in Japanese universities. The data are from a qualitative dataset examining the integration experiences of international academics in Japan. Following the philosophical foundations of purposive sampling in interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), which was applied as a methodological framework, the study recruited a total of 30 participants. The study reveals varied sensemaking strategies among the interviewees, characterized as survivors, pragmatists, and ambitionists. Survivors refer to those who were compelled to remain in their current affiliations often due to constraints related to their academic roles or age restrictions. Pragmatists prioritize the practical benefits of their positions or affiliations, deriving from professional aspects, sociocultural dimensions, and personal considerations. Ambitionist academics generally view experiences in their current affiliations as a stepping stone toward future professional opportunities elsewhere. The study suggests that insufficient dedication to recruiting and retaining international academics may pose potential long-term risks for Japanese higher education institutions (HEIs) in the global academic sphere, affecting their internationally competitive standing and resilience in an evolving academic landscape. The study provides theoretical and practical implications to researchers, university administrators, and policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globalized higher education (HE), internationalized HEIs, and knowledge-based society serve as a transformative power that contributes to a rapidly growing interaction among countries, institutions, and people in recent years (Altbach & Yudkevich, 2017). International academics, which are structured as “importers of knowledge and development” (Seggie & Çalıkoğlu, 2023), have become key actors in this dynamic transformation process that stimulates an increasing number of academics that pursue international mobility (Kim, 2017; Lee & Kuzhabekova, 2018). Factors from various dimensions contribute to this process. The HE literature in Western countries has constantly attributed the international mobility of academics to academic excellence and the well-established economic market of local contexts (Kim, 2017). Despite the dominant status of Western countries, comparatively more tailored immigrant policies and supportive academic and social environments in Asian countries have also gradually attracted numerous international academics (Marginson, 2017). Thus, instead of traditional countries experiencing a brain drain, the role of many Asian countries in the international mobility market has shifted into popular hosting destinations of international academics (Lee & Kuzhabekova, 2018), including Japan. According to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT, 2023a, 2023b), the proportion of international academics in Japan increased from 1.17% in 1983 to 5.10% in 2022.

Scholars widely recognize the significance of international mobility among academics; however, equal concern should be given to their retention, because the turnover of international academics is closely associated with institutional effectiveness such as student competence, the morale of other staff, racial disparity among academics, organizational success, and cost expenditure (Shaw et al., 2021; Welch, 2016). Thus, the retention of international academics is gaining widespread attention in HE studies, which comprises those from dominant hosts of Western countries (Bhopal et al., 2018) and traditional sending countries in Asia (Kim, 2016). Despite the acknowledged distinctive context, the existing literature confirms a positive correlation between the degree of international academics’ integration and their retention at their host affiliations (Kim, 2016; Kim et al., 2022; Luczaj, 2022). Surprisingly, however, a recent study reveals that the majority of international academics are more inclined to remain in their affiliations although many perceived themselves as tokenized symbols of Japanese universities (Chen & Chen, 2023). According to the principles of tokenism, individuals in token positions often find themselves in compromised roles. They endure heavy workloads, are deprived of equal responsibilities, have limited access to opportunities, receive less professional development, and often experience diminished professional advancement prospects. Additionally, they may also suffer from the negative effects of their affiliations, which can be detrimental to their mental health (Brown, 2019; Datta & Bhardwaj, 2015). International academics are depicted as effective agents of systematic reforms and significant importers of advanced scientific competence and diverse sociocultural perspectives, whose future is considered promising and filled with prospects. Hence, the reasons underlying the inclination of international academics to remain in their affiliations despite challenging and uncertain circumstances warrant examination.

The study intends to elucidate how international academics make sense of their decision to remain. The data are part of a qualitative dataset obtained through an examination of the integration experiences of international academics in Japan. The next section of the study offers a literature review followed by a description of the methodology. Based on interview quotations, the fourth section of the study elaborates on the detailed process of data analysis; meanwhile, a discussion of the interview findings is presented. Finally, the study concludes with the key findings and presents their implications and limitations.

Literature review

With the advent of globalized internationalization and the emerging need for knowledge-based societies, international academics have become key stakeholders in global issues and international scientific transformation (Altbach & Yudkevich, 2017), such that increased attention has been given to these unique agents. Given the increasing number of European empires, universities from Western countries, especially the USA and the UK, have long been the predominant actors in attracting international academics (Der Wende, 2015). Thus, a substantial number of previous studies on international academics have been conducted in Western contexts. These studies have been instructive in the illumination of the career trajectories of international academics working in foreign countries, including their motivations (Luczaj & Holy-Luczaj, 2022), integration experiences (Jonasson et al., 2017; Wilkins & Neri, 2019), and satisfaction (Omiteru et al., 2018). Regarding the retention or turnover of international academics in Western destinations, individual (e.g., gender, age, citizenship status, and length of stay), professional (e.g., research opportunities and career prospects), and sociocultural (e.g., lifestyle) factors could profoundly determine this decision-making process (Lawrence et al., 2014; Omiteru et al., 2018).

Recently, investment in the advancement of internationalization reform in non-Western countries and immigration policy restrictions in Western countries have been increasing. Thus, many non-Western countries have been gradually changing from traditional sending countries to alternative hosting countries of international academics (Marginson, 2017; Seggie & Çalıkoğlu, 2023). Similar research trends have been slowly emerging in non-Western countries. An increasing scholarly emphasis has been placed on the demographics, professional characteristics, and perceptions of international academics. For example, scholars have explored the lived experiences of international academics in various countries, including Japan (L. Chen & Huang, 2023), China (Han, 2022), South Korea (Kim et al., 2022), and Turkey (Seggie & Çalıkoğlu, 2023). Similarly, their retention in non-Western countries has gradually attracted scholarly attention. Therefore, researchers have extensively examined their intention to stay or leave and the factors that influence this dynamic process through a quantitative approach. For instance, Awang et al. (2016) found that practical human resources (e.g., professional opportunity and development) and organizational commitment are the two major determinants of the retention of international academics in Malaysian universities. In addition, Kim (2016) examined the relationship between failure in acculturation among international academics and their departure from Korean universities. Similarly, Gress and Shin (2020a, 2020b) confirmed the negative correlation between department cordiality and intention to leave. Moreover, Marini and Xu (2021) reported that professional opportunities, financial allowances, and general working conditions in Chinese universities were favorable elements that lead to the retention of international academics in China. Existing literature yet has not delved into a more detailed exploration of this phenomenon.

In Japan, the academic focus on international academics has become stronger with the increase in endeavors in the internationalization of HE and the recruitment of international academics over the years. Beginning with a questionnaire survey conducted by Kitamura (1989) in the 1980s, subsequent studies on international academics have significantly increased and deepened. Among these studies, several comprehensive ones made particularly notable contributions to the field by investigating the general outlooks, characteristics, and perceptions of international academics through large-scale surveys. Examples of studies that deserve attention include Yonezawa et al. (2014), Fujimura (2016), and Huang (2018a, 2018b). In a related vein, researchers subsequently further explored and analyzed the working and lived experiences of international academics in Japan, which the mainstream existing literature depicted as excluded and pessimistic. The empirical evidence frequently revealed their peripherical status in Japanese universities. For example, many tend to be offered different work roles (e.g., English-related teaching positions), limited participation in decision-making, and restricted career prospects (Brotherhood et al., 2020; Brown, 2019; L. Chen, 2022b; L. Chen & Huang, 2023; Nishikawa, 2021). As such, many have perceived themselves as tokenized symbols of internationalization, whose presence is mainly associated with their distinctive foreign status and the visible foreign appearance of their affiliated universities (Brotherhood et al., 2020; Chen & Huang, 2022; Chen, 2022a). Drawing on the consequences of their academic and social lives, an extremely limited number of studies addressed the satisfaction and well-being of international academics at Japanese universities through quantitative surveys (e.g., Huang & Chen, forthcoming). To date, Yonezawa et al. (2014) reported that international academics in language teaching positions and senior international academics in science, technology, engineering, and math fields tend to express high levels of satisfaction. Parrish et al. (2022) identified the major factors that influence the satisfaction of English instructors with Japanese universities by conducting a national survey on perceived respect, autonomy, departmental relationship, and work-life balance. Additionally, Sakurai and Mason (2022) characterized international academics under three categories according to their well-being in Japan based on scores for stress and sense of belonging. Surprisingly, only Chen and Chen (2023) specifically addressed the career plans of international academics. This notion suggested that the majority of international academics in Japan were more intent on staying for the subsequent 5 years despite the perceived exclusion and tokenization, however, fails to thoroughly analyze the underlying psychological dynamics that underlie each individual.

Despite the growing stream of research on international academics and their perceived importance, the literature on their retention is primarily concerned with the overall trends of their career plans over the next 5 years, such as whether they intend to stay or leave, and the predominant factors that impact their intention and decision-making. Thus, the majority of current studies applied the quantitative approach to examine the correlation between potential factors and their retention/turnover intention, which is of significance. More importantly, however, given the dynamic and complex nature of decision-making, the mechanisms of the formation and interpretation of their intentions/decisions are equally urgent, because they involve a more nuanced subjective anticipation and plan of their future careers.

Methodology

Objective and methodological framework

Given that the majority of the participants expressed a preference to remain in their current affiliations despite the perceived tokenization, the study intends to elucidate how international academics make sense of their decision to stay.

The study applied IPA as a methodological framework, which was developed by Smith (1996), as it has been characterized as the most appropriate method for discovering how individuals understand and make sense of a particular phenomenon. According to Smith et al. (2022), the underpinning philosophies of IPA consist of phenomenology, hermeneutics, and idiography. IPA is rooted in phenomenology because it emphasizes a specific phenomenon. This notion is in line with the idea of phenomenological philosopher Husserl’s (1970) “to the things themselves,” in which things refer to the lived experiences of individuals. IPA aims for a careful and systematic reflection on everyday experiences with a focus on the embodied, cognitive, emotional, and existential dimensions of being in the world. In addition, IPA is concerned with hermeneutics, which is also known as the theory of interpretation, and stresses the role of the researcher in the analytic process of understanding the lived experience of participants (Smith, 2004). A double hermeneutic is involved in IPA, which requires the understanding and engagement of participants and researchers. At the first level, participants make sense of their experiences; researchers then analyze and understand their sensemaking based on their expertise and experiences (Smith, 2004). Finally, as IPA focuses on specific phenomena in specific contexts, the primary value of research lies in the extensive and detailed analyses of unique instances of lived experiences. In contrast to nomothetic, which calls for a group-level conclusion that establishes a general pattern of human behavior, IPA considers each case in detail through a purposive sample of participants, then generates other general conclusions in relation to the personal significance of participants (Smith et al., 2022).

Data collection

Drawing from relevant research (Huang, 2018a, 2018b), the definition of international academics in the current context is based on three primary criteria, namely, individuals holding full-time employment positions at Japanese universities, without a Japanese passport or citizenship, and who completed primary and secondary education outside of Japan. Consequently, individuals who are part-time employees, possess Japanese passports, and completed their junior high or high school education in Japan were excluded.

The participants are part of an interview sample of a project that examined international academics in Japan. The project posed common open-ended questions on their demographic information, challenges, integration experiences, career plans, and relevant follow-up questions through semi-structured interviews, which were conducted from July to November 2020. The language preferences of the participants determined the major languages used, including English, Chinese, and Japanese. However, only eight interviews were conducted face-to-face due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the remaining interviews were conducted remotely using online platforms such as Zoom, Skype, and WeChat. The majority of the interviews, excluding two, were recorded and professionally transcribed to ensure accuracy. The transcriptions underwent a thorough review and received approval from a few of the participants, particularly those without records. The interviews lasted between 40 min and 2 h.

Participant recruitment

The participant recruitment process in the project that examined international academics in Japan involved three methods. First, invitations were disseminated to eligible respondents who agreed to be interviewed in the national survey conducted by Huang (2018a, 2018b). Based on information provided in the survey, formal invitation letters were sent for participation in the interviews. Second, requests were made to potential participants from various Japanese universities. This search was conducted by referring to the information available on the official websites of their respective institutions. This approach aimed to broaden the pool of potential participants. Third, the study employed snowball sampling. The participants identified using this method were primarily introduced or recommended by those who underwent the interview. This approach facilitated the identification of additional participants and expanded the sample size. To achieve diversity among the participants, which could enhance the representativeness and breadth of perspectives, the study considered several personal and organizational attributes, including nationality, gender, position, discipline, contract type, and the location of their affiliations. Finally, the project identified 40 potential participants from seven regions in Japan.

Following the philosophical foundations of purposive sampling in IPA, only those with relatively negative integration experiences who expressed an intention to stay in their affiliations were selected for further analysis in this study, resulting in a total of 30 participants. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the interviewees selected for this study.

Data analysis

According to the updated version of the IPA theory proposed by Smith et al. (2022), the study applied a seven-sequential-step analytic process to identify meaningful patterns and themes emerging from the narratives and experiences:

-

(1)

Carefully review and examine each interview transcript multiple times

-

(2)

Take exploratory notes or comments while reading the transcript to capture initial observations and insights

-

(3)

Create experiential statements by selecting relevant segments from the transcript based on the analysis of the exploratory notes

-

(4)

Pinpoint connections among the experiential statements within each transcript

-

(5)

Systematically label these connections as personal experiential themes (PETs)

-

(6)

Apply the previous steps to analyze each case

-

(7)

Recognize patterns of convergence and divergence across PETs to develop a set of group experiential themes that capture the distinctive and shared characteristics of the lived experiences of the participants

Results and discussion

This section presents the salient findings pertinent to the research objective. The interviewees shared concrete examples and reflections of their lived experiences and career plans. Drawing from the narratives, the interviewees were characterized into three broad categories, namely, survivors, pragmatists, and ambitionists, according to the nuanced interpretation of their sensemaking. Data were analyzed through an inductive process and subsequently discussed.

Survivors: struggling for a living

The first category of interviewees was identified as survivors. Due to the constraints related to their academic roles or age restrictions, the survivor academics are greatly concerned about the possibility of being rehired by another institution. For those who lack scientific visibility, tension due to a neo-liberalized competitive ideology was palpable. In contrast to other contexts, such as South Korea (Gress & Shin, 2020b), many Japanese universities do not set publication quotas for faculty members. The performance of each faculty member, specifically publications and competitive research grants, is integral for promotion and tenure decisions in many positions. Under such a circumstance, achieving scientific visibility and competitiveness appeared to be challenging for international academics, especially language-teaching teachers in general (Brown, 2019; Nishikawa, 2021). This notion can be partially attributed to the fact that language-teaching teachers in Japanese universities tend to be given heavy teaching loads, which limits their allocation of time and effort for research activities and their opportunities for scientific publications and professional advancement (Chen, 2022b; Nishikawa, 2021). When asked about their career plans, therefore, the predominant response from those interviewees was an emphatic affirmation, particularly among those who had secured a relatively stable position (e.g., tenured positions), which necessitates considerable dedication to service within their respective affiliations. This inclination can be predominantly attributed to their disadvantaged status within the job-hunting process. For them, they were more concerned with a job with income than they were with the contextual academic environment. Therefore, remaining is their first choice instead of risking leaving their current affiliations to find a new job. This result relatively supports that of Pustelnikovaite (2021), who acknowledged the stickiness of international academics in the UK. A26 succinctly summed up his sentiment as follows:

When I started, my contract was called Gaikokujinkoushi, which is foreign teacher or lecturer .… So basically, we teach, we are not considered faculty. After that, they changed some parts of the contract but still had a special name, which was Eigokoushi (English teacher) and that means we became faculty. The contract is related to English, but they did remove the Gaikokujin (foreigner), so it’s no longer you are a foreigner. It became, you are an English teacher or English lecturer .… So this year in April, I became tenured. I became a member of the department finally …. So, many foreigners may say: “I’m stuck here.” They may say: “I’ve been here for 20 years and there’s nothing I can do if I leave.” And it’s true in some cases, like if they’ve been here, say, 50 years old, been here for 20 years teaching English. You know, it’s very difficult to start life again outside here.

Another situation observed in the case of survivors is individuals who are approaching retirement. Despite their extensive experience and ability in academia, this population is seemingly inappropriate for job hunting given the hassles of retirement and the preference of HEIs for “high-potential early and mid-career faculty” (Gress & Shin, 2020b, p. 8). Undoubtedly, they also realize and understand the situation and risks of leaving their current positions for another. For them, remaining in the same institution until retirement is seemingly a consensus among those senior academics nearing retirement and between them and their affiliations. Moreover, owing to the implementation of the seniority system in Japan, seasoned academics commonly exhibit prolonged tenures within their respective affiliations. This extended association is correlated with several pragmatic advantages, including heightened esteem from their peers and the attainment of tenured positions. Notably, this phenomenon demonstrates an inverse correlation with the likelihood of their departure (Chen & Chen, 2023; Zhou & Volkwein, 2004). Therefore, regardless of the overall environment of their affiliations, the majority agreed with this notion.

I will be kicked out when I’m 65. My plan is to try to survive till the age of 63. At the age of 63, you can do early retirement. So, if I can survive until 63, at least I can have a choice. And then maybe I can stay until 64 and 65 but for those final 2 years, my salary is cut. So, either at the age of 63 or preferably 65. (A7)

Spurred by globalized neoliberalism, many national HEIs have been gradually managed on the basis of the principles of new public management, including national universities in Japan, which have been incorporated since 2004. Thus, merit‐based practices and policies, such as meritocracy-based recruitment and performance-based funding systems, were adopted as key mechanisms in various aspects, especially the recruitment and assessment processes (Mateos-González & Boliver, 2019). The initial objective of introducing this principle was to promote the efficiency and meritocracy of employees, although policies and rules without clear accountability may lead to ascriptive disparity and inequity across groups such as gender, race, and nationality (Castilla, 2008; Castilla & Benard, 2010). Data analysis was indicative of such institutional practices of Japanese universities in which vulnerable academics, such as the survivor academics in the study, encounter significant hurdles when seeking employment in another position. Their career choice and flexibility were extremely limited by their conditions such as professional invisibility and age restriction. Therefore, for the survivor academics, staying at their current affiliations was not a deliberate strategy; instead, it was their only viable option. To secure their livelihood, they were compelled to remain in their current affiliations with the hope of ensuring their survival.

Pragmatists: prioritizing the practical benefits

The second category of interviewees was characterized as pragmatists. In contrast to survivors, pragmatists were not particularly disadvantaged in terms of job hunting or employment in Japan. Thus, they were concerned with the pragmatic benefits of their positions or affiliations instead of the possibility of acquiring a position. In other words, whether or not their position meets their current needs is of significance. The benefits from professional aspects, sociocultural dimensions, and personal considerations emerged from their narratives, which they believe mainly led to their intention to stay at their current affiliations.

Professional aspects

The determinants in professional aspects refer to work-related factors. The study found that the retention of a few pragmatists was intimately intertwined with their profession; for example, the intellectual focus of scholarly attention is on Japan or Japan-related topics. The pragmatist interviewees expressed the viewpoint that, due to the entrenched organizational structures and cultures of Japanese universities, there may be no significant difference in terms of the overall contextual environments of Japanese HEIs. As a result, these individuals tended to express stronger intentions to remain at their current affiliations. Indeed, academic interests serve as a strong pull-in vector when initiating career plans and decision-making (Marini & Xu, 2021), which is closely associated with personal connections and previous experiences. Beginning with the late 1980s, local Japanese governments actively encouraged the internationalization of the region with a focus on international exchange and international cooperation as key elements of such initiatives (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, 2023). Gradually, Japan witnessed a significant increase in foreign population. Several interviewees shared their previous experiences in Japan prior to achieving their current positions. These experiences included short visits, internships, and engagements in Eikaiwa (English conversation) activities, which echoes Marini and Xu (2021). After initially testing the waters in Japan for a brief period, these individuals decided to stay regardless of the support provided by their affiliations since they discovered that working and living in Japan proved to be highly advantageous and beneficial for their academic pursuits.

I think number one is my research, which is very much related to Japan. This is particularly why I’m here for those years. (A13)

In addition, a few pragmatist interviewees rated their positions as the most effective consideration related to their retention. These interviewees shared detailed experiences since the beginning of their careers and highlighted the hardship of achieving their current positions. Advancement to such positional promotions typically requires a sustained and long-term dedication to their respective affiliations. Legally, the tenure of international academics under Japan’s Labor Contract Act implemented in April 2013 stipulates that employment can transition from fixed-term to permanent status after a 10-year service within an organization (Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare, 2013). The considerable investment of time and effort dedicated to nurturing their roles engenders a sense of “sunk costs,” especially for individuals who have already secured a stable tenured position or are on the verge of obtaining one, as highlighted in prior research (Ryan et al., 2012). Moreover, within the competitive academic landscape in Japan, apprehensions regarding the potential scarcity of permanent employment opportunities and limited prospects for professional advancement in new destinations emerge as significant concerns for academics’ retention (Da Wan & Morshidi, 2018; O’Meara et al., 2014). Therefore, yielding their current positions to relocate to another meant giving up their established academic success thus far at their current affiliations to a large extent.

I have no plan to go back or go anywhere else .... because I have the tenure track for 7 years from this year as an Associate Professor. Within 7 years, I want to get a permanent position. (A12)

I got promoted 2 years ago. And I’m a tenure right now. I would probably stay at my current university until mandatory retirement. (A14)

Sociocultural dimensions

Although professional factors seemingly function as prevailingly favorable incentives for mobility decisions, the study found that sociocultural factors equally contributed to the relocation of pragmatist academics. Many interviewees moved to Japan as culture seekers due to their fondness of Japan or the Japanese culture (Huang & Chen, 2021; Yonezawa et al., 2014). This case is especially common among those from Western countries due to their cultural dissimilarity. These pragmatist interviewees clearly stated that regardless of their positions or affiliations, Japan or the Japanese cultural milieu is the major impetus that stimulated their retention in their affiliations. A similar situation was noted in the case of China (Chen & Zhu, 2022).

I want to stay here in Japan. I like how things work here. I just like Japan. It’s a good place. I love Japanese culture. I think I like that people are very respectful. (A30)

Additionally, a number of interviewees further elaborated on their perceptions and experiences regarding perverse privileges in Japan. They recognized the politeness and hospitality of the Japanese culture. Despite being regarded as tokenized symbols, they were taking advantage of this ambivalent situation. This notion is particularly pertinent to Westerners, who are closely associated with Western supremacy and superior knowledge and skills (Froese, 2010; Marini & Xu, 2021). Others may question and criticize these perverse privileges because they are manifestations of the “legacy of coloniality” in the current HEIs and society (Marini & Xu, 2021). However, some may enjoy the special advantageous treatment of being foreigners in such contexts, which is a privilege they may be unable to enjoy in other countries, reinforcing Damiani and Ghazarian (2023). A few interviewees asserted the following:

I have no complaints about my class load or the amount of time …. This is where maybe my Japanese colleagues, have it much worse, because they are Japanese, they have to do much more committee work than I do. So, I am super lucky. They will be called to the university for all kinds of things .… they will make them work very, very, very hard and put them in lots of committees, and they will be at most weekends doing work. But for me, I’m treated differently in a positive way. (A19)

From Japanese people’s way of looking at the word, Omotenashi (wholeheartedly looking after guests), is helping people before they ask for help …. I go to a restaurant, they give me a fork and they don’t give me Ohashi (chopsticks). So, I think the culture believes it’s helping non-Japanese, which is really nice. (A23)

Personal considerations

Finally, the study identified personal issues as another essential consideration for pragmatist interviewees to remain at their affiliations, including personal preferences for their affiliations or Japan and family links in Japan. Depending on the motivation and experience of each individual, a few international academics consider a number of personal factors. For instance, A21 pointed out that the relatively simple contextual environment, that is, without cumbersome social activities, in Japan is the main incentive for his mobility decision. This aspect should be of concern because an accommodating environment is directly related to a successful integration (Berger et al., 2019) and, thus, higher retention of international academics (Gress & Shin, 2020b).

Additionally, as indicated by the existing literature (Chen & Chen, 2023; Huang & Chen, 2021), family links are characterized as one of the most profoundly influential factors for the relocation of international academics. Among the 30 interviewees, 12 were married to Japanese partners, and many emphasized the significant impact of their Japanese families on their decision-making. The majority of individuals with Japanese spouses often have their intention to stay imposed by their Japanese families, even if their decision to move to Japan may not be entirely motivated by their Japanese partners. A similar situation is also observed in the Chinese context (Marini & Xu, 2021). Family links are of significance for international academics living outside their home countries because, emotionally, they provide a source of love for these expatriates (Chen & Chen, 2023), and in practical terms, the family support system significantly contributes to the care of the academics’ children and household responsibilities (Fernando & Cohen, 2016). Therefore, pragmatist interviewees were more concerned with the feelings and experiences of their family members compared with professional concerns such as position or academic excellence. They typically work and live in places where their Japanese spouse wants to stay such as in their hometown. Their spouses frequently serve as the bridge between them and the local Japanese society and community, which increases their exposure to cultural discourses and norms and contributes to their engagement and integration in the academic and sociocultural settings in practice.

I just became aware of this position at W University (in Tokyo), so I applied for it …. My wife’s family is from Tokyo. So, we’re closer to her family …. my wife is Japanese, and usually, she helps me if I have a particular problem that I need to discuss with the office …. In terms of engaging with Japanese culture, I mean, I certainly do some things with my wife and her family, like, you know, Shōgatsu (Japanese New Year) and things like that. (A5)

Despite varied considerations and experiences, the pragmatist interviewees intend to stay at their current affiliations, because they offer the specific benefits of concern to them. In the decision-making process of whether to stay or leave, they typically compare various conditions between their current affiliations and potential future institutions, which provides a holistic rhetoric and practical evidence. Data analysis reveals that factors stemming from professional aspects, sociocultural dimensions, and personal considerations profoundly influenced their decision-making, which can be attributed to their diverse career anchors and motivations for working in Japan (Huang & Chen, 2021; Huang, 2018a).

Ambitionists: a stepping stone for future careers

The third category was identified as ambitionists. Regardless of professional capability or opportunity, these interviewees embraced the expectations of cosmopolitan norms and borderless mobility settings. They believe that international academics are confronted with more international opportunities and even a need for international mobility in the era of globalization and internationalization. In general, they have relatively international backgrounds and underscore the indispensable value of international mobility during their careers, including the acquisition of international networks, professional knowledge and skills, and scientific impact and productivity (Netz et al., 2020). Therefore, despite their perceptions and knowledge that their affiliated universities may not possess the same level of scientific competitiveness or working conditions as other universities in Western countries, other regions in Asia, or even inside Japan, they continue to remain, because they view their experiences at their current affiliations as a stepping stone toward future professional opportunities elsewhere.

I think, basically I have a lot of good experience and lived in many different countries, I experienced many universities in many places. So, I think I just bring that experience with me. I don’t worry so much about Japanese administration expectations. I just wanted to be happy myself. So, I focus on my research …. If I see a job in China and want to go there, I can go anytime. (A9)

Several reasons could explain their tendency toward ambitionism. First, it should be acknowledged that individuals with ambitious aspirations often set more specific career goals, making them inherently more motivated when making career-related choices and decisions. This can be identified from the following quotation:

I don’t know what will happen yet. There is a lot of uncertainty here. But I won’t go further to bother here, just want to improve my ability .… In the end, I think I will go to the U.S. (A22)

In addition, given the recognized perceptions and feelings of many international academics that they are marginalized tokens in Japanese universities (Brotherhood et al., 2020; Chen, 2022a), another explanation is that they may find themselves in a position in which they could only observe organizational norms without possessing actual rights or authority to actively influence or shape the organizational dynamics (Chen & Zhu, 2022). This trend is particularly prevalent among individuals initially hired in precarious positions, such as those governed by fixed-term contracts. Typically, they remain at their respective institutions for a limited duration and concurrently search for the next position. The use of fixed-term contracts hampers the cultivation of a strong sense of belonging and organizational commitment. Consequently, this situation contributes to perceptions of isolation from their affiliations. Therefore, they were more likely to regard themselves as observers or temporary visitors of their affiliations instead of excessively dwelling on institutional structures and practices. This notion verifies the suspicions and concerns of university administrators in South Korea (Gress & Shin, 2020b), which may also be similar to those in Japanese HEIs.

So, I wonder if there is an opportunity for tenure-track positions after that. Well, judging by the fact that I replaced another international faculty member at the end of his contract, it makes me feel like that’s probably the case for me as well. (A20)

Finally, the independent, fast-paced, and individualistic working style centered on efficiency and self-growth is highly in tandem with neoliberal norms and principles, whose regime stresses performance, efficiency, and self-accountability (Davies & Bansel, 2007). To avoid being discarded by the academic market, ambitionists may endeavor to maximize their research capability and growth. Thus, they view their current positions as a means for gaining valuable experiences and skills that would enhance their prospects for advancement and success in the future instead of criticizing the environmental contexts of their affiliations.

Academics driven by ambitious aspirations, although initially perceived as individuals strongly inclined to remain within their current affiliations, were found, through a more nuanced interpretation, to harbor a momentary inclination, extending perhaps only to a 5-year horizon. They tend to regard their experiences at their present affiliations as stepping stones toward future professional opportunities elsewhere. Consequently, their long-term career aspirations lean more toward departing from their current affiliations. While altering the broader contextual global and domestic academic environment, as well as the individual preferences of each academic, may pose challenges, certain initiatives, such as the implementation of a more supportive system and the provision of stable positions (Brotherhood & Patterson, 2023; Chen, 2022b), aimed at integrating international academics into their host affiliations, could prove beneficial.

Conclusion

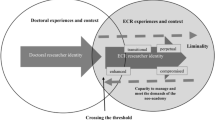

The study examines the sensemaking of international academics in terms of their decisions to remain at their affiliations despite perceptual unaccommodating host environments and perceptions of being tokenized. While scholarly attention has persistently focused on the typology of international academics in Japan, including their demographics, work roles (Huang, 2018b), integration (Brotherhood et al., 2020), and well-being (Sakurai & Mason, 2022), this study addresses a crucial aspect of internationalization by recognizing the indispensable role of retaining minority academics (Chun & Evans, 2009). Thus, the study proposes a significant framework for advancing institutional internationalization in Japan based on the retention of international academics. The study reveals varied strategic sensemaking among the interviewees, characterized as survivors, pragmatists, and ambitionists. Survivors refer to those who were compelled to remain in their current affiliations due to constraints related to their academic roles or age restrictions. In addition, pragmatists prioritize the pragmatic benefits of their positions or affiliations deriving from professional aspects, sociocultural dimensions, and personal considerations. Ambitionist academics generally viewed their experiences at their current affiliations as a stepping stone toward future professional opportunities elsewhere.

In the context of HE internationalization in Japan, recognizing a certain degree of success in the recruitment of international academics in Japanese HEIs is essential, as emphasized by Huang (2019) on diversification in terms of international academics’ nationality and work roles. While Japanese internationalization policies and initiatives may not explicitly stress the integration and retention of this population, the study provides empirical evidence on this matter. Notably, however, the educational system in Japan, which is typically described as self-contained and self-sufficient (Teichler, 2019), has led to a situation in which many Japanese academics undertake limited experiences in studying abroad and many international academics were once inbound international students at Japanese universities (Kakuchi, 2017). The Japanese academic job market frequently supports them throughout their careers. Therefore, the sociocultural and familial reasons that stem from their previous experiences in Japan profoundly stimulate pragmatist academics’ decision-making to remain in their current affiliations, reinforcing existing literature (Huang, 2019; Huang & Chen, 2021). Additionally, Japanese universities tend to favor the recruitment of international academics with knowledge of Japan and familiarity with Japanese organizational culture due to reluctance to fundamental reforms (Chen, 2022a, 2022b). Hence, the recruitment of international academics may be largely linked to addressing Japan’s labor shortage and their familiarity with the country, rather than relying on their academic qualifications and excellence.

Furthermore, the study suggests that ambitionist academics, which pose a context that differs from that of survivors, are essentially using their experience in Japan as a stepping stone for their future careers. Even though initially perceived as individuals significantly inclined to remain in their current affiliations, the in-depth analysis in the study revealed that this inclination was momentary for the ambitionist academics, extending probably only to a 5-year horizon. Regarding their long-term career aspirations, their inclination leaned more toward departing from their current affiliations. This observation supplements the conclusions drawn in a prior study (Chen & Chen, 2023). Under these circumstances, the recruitment and more importantly, retention of such ambitious international academics are critical. They typically prove to be excellent scholars without Japanese backgrounds or family ties (Rappleye & Vickers, 2015). However, Japanese HEIs’ resistance to reform (Brotherhood et al., 2020; L. Chen & Huang, 2023), support deficiencies (Brotherhood & Patterson, 2023), relatively lower investment in research compared to countries like China, a recent decline in academic publications (MEXT, 2023b), and limited opportunities for academic advancement and the availability of stable positions (Chen & Huang, 2023) have made it challenging to attract strong international applicants, as noted by Rappleye and Vickers (2015). This situation heightens the likelihood of the departure of international academics, particularly individuals with ambitious aspirations as outlined in this study, who potentially bear the capacity to substantially contribute to the academic prowess, scientific advancements, and technological progression within Japan’s HE landscapes. Therefore, insufficient dedication to recruiting and retaining international academics may pose potential long-term risks for Japanese HEIs in the global academic sphere, affecting their internationally competitive standing and resilience in an evolving academic landscape.

Drawing on the sensemaking of the intention of international academics to stay at their affiliations despite their perceptual tokenization, the study offers the following implications. First, the study hopes that the empirical evidence can contribute to the drivers of globalized internationalization of HEIs outside Japan, especially those with similar political and sociocultural contexts such as China and South Korea. In addition, given the complexity of the decision-making process, this study argues that a scholarly emphasis should be placed on the career trajectory of international academics to explore their experiences through a detailed and nuanced analysis. Meanwhile, whether a transfer occurs across categories of international academics, and, if so, under what circumstances, warrants further analysis. Moreover, the study reinforces the need for an accommodating academic environment. Organizational structure and cultural norms strongly influence the possibility of the retention of international academics despite their willingness to stay. Therefore, a comprehensive approach that encompasses political strategies, institutional initiatives, and individual endeavors should be proposed and implemented accordingly.

Several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, it exclusively focuses on international academics within Japanese universities, which limits the generalizability of the findings to international academics in other educational institutions in Japan or HEIs elsewhere. Therefore, caution should be exercised when applying the findings beyond the scope of the study. In addition, due to the limited number of interview participants, the study acknowledges that the influences from certain demographics of the interviewees, specifically factors like gender and nationality, on their sensemaking processes may not be comprehensively measured. However, recognizing that these factors may continue to hold potential significance in understanding the experiences of international academics is important. Furthermore, the data used are part of a complete interview database and, thus, pose certain drawbacks, which are likely to limit the depth of data analysis and interpretation. Finally, individuals who voluntarily engage in interviews may potentially lean toward being appointed in more stable positions, showcasing a greater integration into Japanese HEIs, and consequently demonstrating a heightened intention to remain within their affiliations. It is crucial to recognize the potential presence of selective bias in the recruitment of interviewees for the study.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Altbach, P. G., & Yudkevich, M. (2017). Twenty-first century mobility: the role of international faculty. International Higher Education, 90, 8–10. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.90.9995

Awang, M., Ismail, R., Hamid, S. A., & Yusof, H. (2016). Intention to leave among self-initiated academic expatriate in public higher education institution. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 6(11), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v6-i11/2381

Berger, R., Safdar, S., Spieß, E., Bekk, M., & Font, A. (2019). Acculturation of Erasmus students: using the multidimensional individual difference acculturation model framework. International Journal of Psychology, 54(6), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12526

Bhopal, K., Brown, H., & Jackson, J. (2018). Should I stay or should I go? BME academics and the decision to leave UK higher education. In Arday, J. & Mirza, H. S. (Eds.), Dismantling race in higher education (pp. 125–139). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60261-5_7

Brotherhood, T., & Patterson, A. S. (2023). International faculty: exploring the relationship between on-campus support and off-campus integration. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01124-7

Brotherhood, T., Hammond, C. D., & Kim, Y. (2020). Towards an actor-centered typology of internationalization: a study of junior international faculty in Japanese universities. Higher Education, 79(3), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00420-5

Brown, C. A. (2019). Foreign faculty tokenism, English, and “internationalization” in a Japanese university. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 39(3), 404–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1598850

Castilla, E. J. (2008). Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1479–1526. https://doi.org/10.1086/588738

Castilla, E. J., & Benard, S. (2010). The paradox of meritocracy in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(4), 543–676. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.4.543

Chen, L. (2022a). How do international faculty at Japanese universities view their integration? Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00803-7

Chen, L. (2022b). Key issues impeding the integration of international faculty at Japanese universities. Asia Pacific Education Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09764-7

Chen, L. (2024). Tokenized but remaining: how do international academics make sense of their decision to remain in Japanese universities? Review of Philosophy and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01191-4

Chen, J., & Zhu, J. (2022). False anticipation and misfits in a cross-cultural setting: international scholars working in Chinese universities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 26(3), 352–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315320976039

Chen, L., & Chen, L. (2023). To stay or to leave: The turnover intentions of international academics at Japanese universities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 102831532311648. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153231164842

Chen, L., & Huang, F. (2022). The integration experiences of international academics at Japanese universities. [Working paper No. 80.]. CGHE, Department of Education, University of Oxford. Retrieved on 14th February 2023 from https://www.researchcghe.org/publications/working-paper/the-integration-experiences-of-international-academics-at-japanese-universities/

Chen, L., & Huang, F. (2023). Neoliberalism, internationalization, Japanese exclusionism: The integration experiences of international academics at Japanese universities. Studies in Higher Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2283094

Chun, E., & Evans, A. (2009). Bridging the diversity divide–Globalization and reciprocal empowerment in higher education. ASHE Higher Education Report, 35(1), 1–144.

Da Wan, C., & Morshidi, S. (2018). International academics in Malaysian public universities: recruitment, integration, and retention. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19(2), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9534-9

Damiani, J., & Ghazarian, P. (2023). At the borderlands of higher education in Japan and Korea: a duoethnography. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(2), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09779-0

Datta, S., & Bhardwaj, G. (2015). Tokenism at workplace: numbers and beyond. International Journal of Current Engineering and Technology, 5(1), 199–205.

Davies, B., & Bansel, P. (2007). Neoliberalism and education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390701281751

Fernando, W. D. A., & Cohen, L. (2016). Exploring career advantages of highly skilled migrants: a study of Indian academics in the UK. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(12), 1277–1298. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1072101

Froese, F. J. (2010). Acculturation experiences in Korea and Japan. Culture & Psychology, 16(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X10371138

Fujimura, M. (2016). Gaikokujin kyoin kara mita Nippon no daigaku no kokusaika (The internationalization of Japanese universities from the perspective of international faculty) (in Japanese). The differentiation of university by mission and its international trends. Strategic research project series, 10, 67–133. Research Institute for Higher Education, Hiroshima University.

Gress, D. R., & Shin, J. (2020a). Diversity, work environment, and governance participation: a study of expatriate faculty perceptions at a Korean university. Journal of Institutional Research South East Asia, 18(1), 1–20. http://www.seaairweb.info/journal/JIRSEA_v18_n1_2020.pdf#page=12

Gress, D. R., & Shin, J. (2020b). Perceptual differences between expatriate faculty and senior managers regarding acculturation at a Korean university. The Social Science Journal, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1813863

Han, S. (2022). Empowered or disempowered by mobility? Experience of international academics in China. Studies in Higher Education, 47(6), 1256–1270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1876649

Huang, F. (2018a). Foreign faculty at Japanese universities: profiles and motivations. Higher Education Quarterly, 72(3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12167

Huang, F. (2018b). International faculty at Japanese universities: their demographic characteristics and work roles. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19(2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9536-7

Huang, F. (2019). Changes to internationalization of Japan’s higher education? An analysis of main findings from two national surveys in 2008 and 2017. In D. E. Neubauer, K. H. Mok, & S. Edwards (Eds.), Contesting globalization and internationalization of higher education (pp. 95–108). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26230-3_8

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Northwestern University Press.

Huang, F., & Chen, L. (2021). Chinese faculty members at Japanese universities: who are they and why do they work in Japan? ECNU Review of Education, 209653112098587. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120985877

Huang, F., & Chen, L. (forthcoming). A comparative study of Chinese/Korean faculty and British/American faculty in Japanese universities. ECNU Review of Education.

Jonasson, C., Lauring, J., Selmer, J., & Trembath, J.-L. (2017). Job resources and demands for expatriate academics: linking teacher-student relations, intercultural adjustment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Global Mobility: the Home of Expatriate Management Research, 5(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-05-2016-0015

Kakuchi, S. (2017). Push for foreign students to stay on to work in Japan. Retrieved on 20th May 2023 from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20170316184126205

Kim, S. (2016). Western faculty ‘flight risk’ at a Korean university and the complexities of internationalisation in Asian higher education. Comparative Education, 52(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2015.1125620

Kim, T. (2017). Academic mobility, transnational identity capital, and stratification under conditions of academic capitalism. Higher Education, 73(6), 981–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0118-0

Kim, D., Yoo, S.-S., Sohn, H., & Sonneveldt, E. L. (2022). The segmented mobility of globally mobile academics: a case study of foreign professors at a Korean university. Compare: a Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(8), 1259–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1860737

Kitamura, K. (1989). Daigaku kyōiku no kokusaika: Soto kara mita Nihon no daigaku (Internationalization of university education: Japanese universities from the outside). Tamagawa Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Lawrence, J. H., Celis, S., Kim, H. S., Lipson, S. K., & Tong, X. (2014). To stay or not to stay: retention of Asian international faculty in STEM fields. Higher Education, 67(5), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9658-0

Lee, J. T., & Kuzhabekova, A. (2018). Reverse flow in academic mobility from core to periphery: motivations of international faculty working in Kazakhstan. Higher Education, 76(2), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0213-2

Luczaj, K. (2022). Overworked and underpaid: why foreign-born academics in Central Europe cannot focus on innovative research and quality teaching. Higher Education Policy, 35(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-020-00191-0

Luczaj, K., & Holy-Luczaj, M. (2022). International academics in the peripheries. A qualitative meta-analysis across fifteen countries. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2021.2023322

Marginson, S. (2017). Brexit: Challenges for universities in hard times. International Higher Education, 88, 8–10. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.88.9682

Marini, G., & Xu, X. (2021). “The golden guests”? International faculty in mainland Chinese universities. Retrieved on 21st May 2023 from https://srhe.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/SRHE-Research-Report_Marini_Xu_Oct-2021_Final.pdf

Mateos-González, J. L., & Boliver, V. (2019). Performance-based university funding and the drive towards ‘institutional meritocracy’ in Italy. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2018.1497947

MEXT. (2023a). Gakkou Kihon Chousa Koutou Kyouiku Kikan [Basic investigation of schools: Higher education institutions]. Retrieved on 8th December 2023 from https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00400001&tstat=000001011528&cycle=0&tclass1=000001212520&tclass2=000001212545&tclass3=000001212546&tclass4=000001212548&cycle_facet=cycle&tclass5val=0&metadata=1&data=1

MEXT. (2023b). Trends in our country’s research capabilities [Wagakuni no kenkyuryoku no douko]. Retrieved on 8th December 2023 from https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon/kaigi/special/reform/wg7/20230420/shiryou1.pdf

MIC (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). (2023). Promoting the internationalization of the region. Retrieved on 20th November 2023 from https://www.soumu.go.jp/kokusai/index.html

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2013). Key points of the revision of the labor contract act [Roudoukeiyakuho kaisei no pointo]. Retrieved on 5th November 2023 from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/seisakunitsuite/bunya/koyou_roudou/roudoukijun/keiyaku/kaisei/dl/h240829-01.pdf

Netz, N., Hampel, S., & Aman, V. (2020). What effects does international mobility have on scientists’ careers? A systematic review. Research Evaluation, 29(3), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvaa007

Nishikawa, T. (2021). The internationalization of Japanese universities: A case study on the integration of foreign faculty. https://doi.org/10.17638/03118952

O’Meara, K., Lounder, A., & Campbell, C. M. (2014). To heaven or hell: sensemaking about why faculty leave. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(5), 603–632. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2014.0027

Omiteru, E., Martinez, J., Tsemunhu, R., & Asola, E. F. (2018). Higher education experiences of international faculty in the US deep south. Journal of Multicultural Affairs, 3(2), 3.

Parrish, M., Kithae, P., Michael, P., & Peter, K. (2022). Thematic analysis of factors contributing to the job satisfaction of foreign university instructors in Japan according to employment status. 甲南大学マネジメント創造学部HSMR編集委員会. https://doi.org/10.14990/00004083

Pustelnikovaite, T. (2021). Locked out, locked in and stuck: exploring migrant academics’ experiences of moving to the UK. Higher Education, 82(4), 783–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00640-0

Rappleye, J., & Vickers, E. (2015). Can Japanese universities really become super global? Retrieved on 1st May 2023 from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20151103154757426

Ryan, J. F., Healy, R., & Sullivan, J. (2012). Oh, won’t you stay? Predictors of faculty intent to leave a public research university. Higher Education, 63(4), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9448-5

Sakurai, Y., & Mason, S. (2022). Foreign early career academics’ well-being profiles at workplaces in Japan: a person-oriented approach. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00978-7

Seggie, F. N., & Çalıkoğlu, A. (2023). Changing patterns of international academic mobility: the experiences of Western-origin faculty members in Turkey. Compare: a Journal of Comparative and International Education, 53(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1868975

Shaw, A. K., Accolla, C., Chacón, J. M., Mueller, T. L., Vaugeois, M., Yang, Y., Sekar, N., & Stanton, D. E. (2021). Differential retention contributes to racial/ethnic disparity in US academia. PLoS One, 16(12), e0259710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259710

Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology & Health, 11(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400256

Smith, J. A. (2004). Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1(1), 39–54.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2022). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Teichler, U. (2019). The academics and their institutional environment in Japan–a view from outside. Contemporary Japan, 31(2), 234–263.

Van Der Wende, M. (2015). International academic mobility: towards a concentration of the minds in Europe. European Review, 23(S1), S70–S88. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798714000799

Welch, A. (2016). Audit culture and academic production: re-shaping Australian social science research output 1993–2013. Higher Education Policy, 29(4), 511–538. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0022-8

Wilkins, S., & Neri, S. (2019). Managing faculty in transnational higher education: expatriate academics at international branch campuses. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(4), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318814200

Yonezawa, A., Ishida, K., & Horta, H. (2014). The long-term internationalization of higher education in Japan: A survey of non-Japanese faculty members in Japanese universities. In Internationalization of Higher Education in East Asia (pp. 179-191). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315881607-10/long-term-internationalization-higher-education-japan-akiyoshi-yonezawa-kenji-ishida-hugo-horta

Zhou, Y., & Volkwein, J. F. (2004). Examining the influences on faculty departure intentions: a comparison of tenured versus nontenured faculty at research universities using NSOPF-99. Research in Higher Education, 45(2), 139–176. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RIHE.0000015693.38603.4c

Acknowledgements

The study is a part of the author’s Ph.D. dissertation. The author would like to express her enormous gratitude to her Ph.D. supervisor Professor Futao Huang from Hiroshima University Japan for his generous support during the journey and continuous assistance beyond the journey, and also to the interviewees of the study for their kind help.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Osaka University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L. Tokenized but remaining: how do international academics make sense of their decision to remain in Japanese universities?. High Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01191-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01191-4