Abstract

This interdisciplinary paper brings together scholarship from the fields of education, psychology, sociology and performance to shed light on three pedagogy and learning strategies to support learners recontextualise knowledge between higher education and work contexts. These strategies include offering multiple different types of performance activities and modes of engagement with different types of people (learners/experts, different cultures, ages, etc.). Secondly, it provides spaces to fail and enables testing of personal strategies with limited risk. Finally, it supports students in connecting ideas and experiences from the past, across educational experiences of different performance practices and into wider contexts such as professional work.

The research, which is a pilot, recognises the ways in which these strategies align with and operationalise Guile’s (2010) concept of recontextualisation, offering pedagogues tools to support learning in a similar way in which the concept of scaffolding might be seen to operationalise Vygotsky’s notion of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

This pilot study uses semi-structured interviews and a thematic analysis approach with five graduates from an undergraduate drama degree programme in London. We recognise drama as a practical degree subject and as such consider our findings as generalisable to wider practical fields and disciplines, such as engineering and nursing education, and as having international relevance. The work offers a novel approach to conceptualising and evaluating the ways in which students deploy taught knowledge beyond the classroom, in work. It offers and augments arguments around the ways in which students bridge practice and learning from within the HEI and beyond it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This interdisciplinary paper brings together socio-cultural theories of learning (Dreier, 1999 & 2008, Lave & Wenger, 1991, Guile, 2010), failure theory in relation to education and entrepreneurialism (Stretch & Roehrig, 2021) and performance theory (Schechner, 2013). In doing so, we examine the ways in which students navigate complex individual trajectories across a practical Higher Education (HE) programme situated within a specialist building. This case study is of a BA Drama programme at the Bathway Theatre in London but could arguably refer to any bespoke site where a practical degree is studied internationally. The Bathway Theatre comprises of a complex set of teaching and learning spaces including staff offices, performance studios and making workshops (including set and costume) and houses a range of programmes traditionally associated with a ‘Drama Department’ or a ‘School of Arts’. Through the synthesis of theoretical literature and semi-structured interview data, the paper sheds light on three pedagogic and learning strategies whereby students on practical degrees learn how to deploy past knowledge in personal ways, within the newly situated context of Higher Education (HE) and after graduation within work. These we argue, operationalise the three pedagogic and learning strategies offered by Guile (2010): restructure, reposition and recontextualise. Strategies that support students to navigate between the contexts of education and work.

Through these methods of restructure, reposition and recontextualise, graduates develop unique ways of working and thinking across a broad nexus of practices involved in drama, theatre-making and performance. We conclude by arguing that there are opportunities for pedagogues to make explicit these strategies not just within an HE drama programme but across other practical and vocational programmes, such as engineering, nursing or science. By recognising that the situated learning activity of Higher Education is different to that of work, this paper offers practical and operational insight into pedagogy and learning strategies to bridge this education–work divide.

In order to make this case, the paper builds a critical framework through four turns before synthesising this with our empirical research phase.

Firs, the paper will begin by theoretically conceptualising the ways in which students navigate the multiple practical and experiential learning activities within a university theatre as navigating a nexus of theatre practice. It will do this by drawing together Schechner’s Web (2013) from performance theory and Dreier’s nexus of situated social practices (Dreier, 1999, 2008) from educational psychology. It will describe the ways in which people navigate personal trajectories, moving from different social, situated activities. This will enable the paper to create a critical language to outline the real-world practices which take place within a university theatre, where drama students interact with peers from different years, theatre professionals and community groups, each undertaking different types of performance activity.

Second, the paper outlines Vygotsky (1987) formative socio-cultural learning theory of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which frames the difference between what is known by individuals and areas of ‘potential development’ (38). We build upon this by recognising how this is operationalised by Wood et al. (1976) through the process of scaffolding. We do this threefold to firstly highlight learning as a social act. Secondly, to recognise the relationship between the conceptual understanding of learning (ZPD) and practical pedagogic strategies which align to it (scaffolding). Finally, to develop a socio-spatial language to consider the periphery of the ZPD, beyond the scaffold. In doing so this allows for the paper’s third turn, which introduces risk and failure as part of an individual’s learning strategy. This is conceptualised through Stretch and Roehrig (2021) and Lattacher and Wdowiak (2020).

The final turn of the conceptual framework is to introduce Guile (2010) to consider the process of recontextualisation as a conceptual way to understand how individuals bring past knowledge and experience to support new situated knowledge.

In addition to synthesising the literature above, we have undertaken semi-structured interviews with five graduates who each graduated with the same BA Hons Drama degree over the past 5 years, and who learnt within the same theatre complex of the Bathway Theatre. The research takes a Kvalian approach to both research design and thematising data. We particularly enjoyed the way Kvale describes the interviewer as a traveller gathering stories to be retold upon returning home (Kvale, 1996).

The data begins to yield interesting narratives around the ways in which graduates navigated the complex nexus of social practices which take place in university theatres. Our empirical research sheds light on three implicit pedagogy strategies, within the practical discipline of performance, which appear to operationalise Guile’s (2010) concepts of restructure, reposition and recontextualise. The implicit strategies we have identified are:

-

1.

To offer multiple different types of performance activities and modes of engagement with different types of people (learner/expert, different cultures, ages, etc.). A strategy of restructuring.

-

2.

To provide spaces to fail, enable testing of personal strategies with limited risk. A strategy of repositioning.

-

3.

To support students in connecting ideas and experiences from the past, across educational experiences of different performance practices and into wider—such as professional work. A strategy to recontextualise.

We propose that these strategies may be used by pedagogues to support students in bringing together types of knowledge across learning activities and are relevant to wider practical and vocational degree programmes. We hope to extend this pilot project in the future, interviewing a wider range of performance practitioners and academics to understand how the nexus of HEI theatre practices has altered their professional work activity.

Navigating a nexus of practices within a university theatre

This section begins by bringing together eminent performance studies scholar Richard Schechner (2013) with educational psychologist Ole Drier’s concepts of the ‘personal trajectory’ (1999) and the nexus of situated social practices (1999, 2008) to theoretically conceptualise the nexus of performance activity which takes place within a university theatre. We are using a performance scholar to frame performance as an umbrella term to describe different types of performance practice which are similar but distinct. We recognise how different professions use umbrella terms to link together different modes of related activity and ways of working. A medical doctor might be a specialist GP or specialise in brain or heart surgery. An engineer might build bridges or mend cars. At the heart, these professional domains are umbrellas which bring together connected yet distinct ways of working. As such performance, as a context, is analogous to different types of professional contexts and may be extrapolated beyond that of the field of theatre and performance.

Richard Schechner’s (2013) arguments for performance are considered the cornerstone of performance studies, a field of study which looks at the ways in which performance is pervasive, as a pivotal component of both social and cultural activity. One of Schechner’s core concepts is the idea of a web which connects different modes of performance together, commonly known as ‘Schechner’s web’ (2013, p.18). Within Schechner’s web, different performance methods hang together with each other to form an inter-connected nexus of practices which range from the performance of the everyday, through to experimental performance, European theatre traditions, traditions from Africa, Eurasia and the Pacific and alongside different modes of ritual. As such, performance as an activity is made manifest in diverse ways. One of the roles of a university drama programme is to enable students to explore the multiple tangential methods of performance activities and enable students to make links across these, both theoretically and practically, in order to learn how to participate in these different theatre practices. Students are required to navigate a curriculum where different theatre methods are taught within modular structures, practically experimenting with and critically reflecting on what is being taught.

With some synergy with Schechner, psychologist Ole Dreier (1999, 2008) conceives situated social practices as a nexus of interconnected activities which are encountered along an individual’s personal trajectory. Here, Dreier makes explicit the ways in which individuals encounter processional situated and social activities throughout our daily lives, arriving at social practices with the knowledge of past activities. Practices here are considered as situated, taking place within evolving contexts with others. Each situated activity, across an individual’s trajectory, ‘hang[s] together’ (Dreier, 2008: 26) in a nexus of connected social practices. ‘Hang together’ is from the German zusammenhang, to describe:

‘how contexts, as parts, hang together in complex constellations of parts in relation to other, more or less definite parts’ instead of ‘referring to a well-bounded all-encompassing totality’. (Dreier, 2008: 26)

In this way, each activity may influence how other activities are understood. Moreover, Dreier conceives practice as trans-local, where individuals participate in multiple social practices, and where each practice may take place in multiple locations (ibid: 10). This has been seen clearly with the rise of hybrid-working, where similar work may be conducted both in a home office and at work. Whilst trans-locality speaks to the multiple locations of practice, it also recognises the shift in time between work in these locations, where we bring to each location new experience. Within drama, as with wider practical disciplines, such as engineering or nursing, different locations offer different possibilities. A workshop with tools, a studio with a dance floor and a home office all have very different purposes, yet the practices of performance may take place across all of them. A puppet made in the workshop, used in the studio or with scripted lines practiced at home. Each location cannot be seen as interchangeable with another. Different individuals, even those involved in the same group, will have had a range of experiences across these locations and understood those activities in different ways given their unique socio-cultural perspective and past knowledge.

By bringing together Schechner and Dreier, we make explicit the ways individuals, who occupy university theatre spaces, undertake different modes of performance with others, from unique positions. Where individuals navigate a personal nexus of social practice which creates an individual socio-cultural perspective. Students arrive at an HEI theatre or other building having previously encountered performance practices in their everyday lives, having watched performances on TV or in theatres and having been taught drama in educational contexts. We suggest that these previous socio-cultural encounters are brought with them, as their lived experience, into the situated decision-making contexts of HEI performance activity. As such, the paper turns to consider the seminal socio-cultural learning theories of Vygotsky (1987) and Wood et al. (1976) before augmenting these with contemporary theories of risk and failure (Lattacher & Wdowiak, 2020; Stretch & Roehrig, 2021) and recontextualisation (Guile, 2010). We do this to think through the iterative ways in which theatre-based performance practices are encountered within an HEI, and how through a rehearsal process of trial and error, individuals push the boundaries of their knowledge.

Conceptualising learning: a socio-cultural perspective

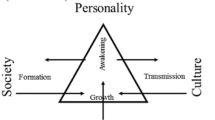

Vygotsky’s cultural learning theory, presented in his book Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Process (1997), was groundbreaking for its time. Although originally published in Russian in 1930, its English translation in 1978 and subsequent re-publication in 1997 has led to its widespread acceptance in contemporary social-cultural literature on learning. Vygotsky emphasised the cultural nature of learning, highlighting the role of psychological tools such as language and symbols in mediating understanding and meaning-making with others. He viewed perception as a combination of biological phenomena and cultural experience. This is illustrated in his conceptual framework, the mediational triangle. In this triangle ‘subject’ (i.e., person), ‘object’ (i.e., the purpose of activity) and ‘mediating artefacts’ (i.e., resources to accomplish the purpose) are interconnected (Guile, 2010: 87 referencing Vygotsky, 1987: 40).

By framing learning as a social experience, Vygotsky introduced the ways in which knowledge is co-constructed with others, both peers and pedagogues. This can be seen in the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The ZPD refers to the difference between a learner’s actual and potential development. The pedagogue needs to pitch teaching and learning activities at an appropriate level, allowing individuals to probe areas of unknown knowledge in structured ways. Vygotsky’s ideas have been further developed by his contemporaries, notably Wood et al. (1976), who operationalised the ZPD by introducing scaffolding.

In ‘The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving’, Wood et al. (1976) present the concept of scaffolding, which they defined as:

a process that enables a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his unassisted efforts. This scaffolding consists essentially of the adult “controlling” those elements of the task that are initially beyond the learner’s capacity, thus permitting him to concentrate upon and complete only those elements that are within the range of competence. (Wood et al., 1976: 90)

This is explained as a six-phase process. The first phase, recruitment, involves the tutor getting students excited and onboarding them to the activity. Next, the tutor simplifies and breaks down the task into smaller parts and reduces the ‘degrees of freedom’ (98), allowing an individual to focus on specific components. The tutor provides ‘direction maintenance’ to ensure that learners stay on track and can check in with the tutor if needed. As the task progresses, the tutor marks ‘critical features’ and discrepancies, guiding the student towards the correct solution. The tutor must also provide enough support to prevent frustration but not create excessive dependence. Finally, the tutor must ‘demonstrate’ an idealised solution for the problem, hoping that the student will imitate and reproduce appropriate solutions.

The seminal learning theories of Vygotsky’s ZPD and Wood et al.’ (1976) scaffolding recognise pedagogy and learning as social acts, where the pedagogue has a responsibility to structure activity to support learning. Wood et al.’(1976) offer of scaffolding can be seen to operationalise the conceptual work of the ZPD by offering a practical strategy for pedagogues. The socio-spatial language of the ZPD and scaffold describe the conceptual space between a learner’s actual development and potential development. To develop this idea further, the paper will conceptualise the ways individuals may test the outer boundary of this space, beyond the scaffold. It will do this to open the idea of failure as a natural part of learning. In addition, having recognised, through Dreier, that past knowledge and experience are brought into a new experience, what appears missing from these formative learning theories is an acknowledgment of the ways past knowledge is recontextualized in newly situated contexts. The final turn of this paper’s conceptual framework is to consider Guile’s (2010) concept of restructuring, repositioning and recontextualising. Once this is explored, we offer early insights from our pilot which appears to reveal three implicit pedagogic strategies to operationalise Guile’s conceptualisation.

Conceptualising learning: testing the boundaries of situated knowledge

This section conceptualises the learning which takes place within the ZPD twofold. First, resonating with Schechner, we think through the ways in which individuals encounter new modes of theatre practice. We can consider the multiple ways in which learners understand theatre practices within HEI’s: from reading literature, lectures, and workshops as well as attempting to take on these practices through a practical process of trial and error and experimentation. We argue that the scaffolding, offered by pedagogues, changes the relationship individual learners have to risk and failure and as such enables individuals to reflect on what went wrong and what they might do differently in the future. An iterative sequence of small failure events. Trial and error. This ‘train[s] creativity [as]…a skill’ which can be ‘developed and utilised’ (Stretch & Roehrig, 2021, p.126). Second, resonating with Dreier, we consider the ways in which individuals bring with them past knowledge into new and potentially more complex situated contexts. We do this through the tri-fold processes of restructuring, repositioning and recontextualising (Guile, 2010, p.182). To begin this section, we turn to the idea of creative risk and failure within the ZPD.

A learner’s development can be spatially described as a series of circles which, like a ripple in a pond, expand out from a centre. We can describe that centre as the learner’s actual development, where individuals have experience and knowledge which they have learnt in a specific situated context. The ZPD can then be described to encircle and expand out from that central core, an area of potential development. Within this visualisation, we argue that moving from the core understanding towards areas of unknowing requires individuals to open up to creative risk, and the potential for failure. The nature of learning practical activities which are creative requires individuals, such as those within theatre and performance, to iteratively try out an activity and reflect upon it. For Stretch and Roehrig (2021: 126) ‘the iterative nature of the engineering design process is intrinsically linked to reflection on failure, which both draws on the creative potential of engineers and results in innovation through creativity’. We recognise this engineering design process as similar to the processes of rehearsing, devising and creating performance, where we iteratively try out new ideas, with others. This observation is shared by Stretch and Roehrig (ibid) by aligning their work in STEM with Dewy, as cited by Koschmann et al (2009).

Dewy recognised how individuals in fields such as art, science, and education intentionally seek out challenging situations where they may encounter failures. This approach allows them to gain a deeper understanding and knowledge by troubleshooting and resolving what went wrong. Instead of fearing failure, Dewy views it as a valuable learning process that begins with analysing the failure itself. By examining the events leading up to the failure, they can identify the root cause and better understand how to improve the activity in the future. Here, failure as a strategy for learning allows learners to ‘forward gaze’ where failure ‘provides the momentum and creativity to propose new solutions’ (Stretch & Roehrig, 2021, p.125).

Whilst performance activity involves groups, failure is a personalized experience (Lattacher & Wdowiak, 2020). Citing the experiential learning perspective of Kolb (1984), Lattacher and Wdowiak discuss the role of reflective observation in the process of experiential learning, including individual ‘emotional patterns’. This leads to individuals conceptualising what has been learnt resulting in internalised conclusions and insights. This includes insights about one’s own strengths and weaknesses, skills, attitudes, beliefs, areas for development as well as shaping interests and motivations. In this way, failure enables learners to reposition past knowledge and unlearn what does not work. ‘Repositioning’ is a process of learning picked up by education professor David Guile (2010) as one of three processes which enable past knowledge to be utilised in current situated activities across contexts. In doing so, Guile’s work enables a language to discuss the ways an individual’s past experience is brought into and used in educational contexts and how knowledge developed in educational experience can be utilised after graduation into the world of work.

Guile does this from three positions: philosophical, sociological and pedagogical. Firstly, from a philosophical standpoint, he acknowledges the relationship and differences between different forms of knowledge whilst identifying the criteria for mediating knowledge embedded in practice. Secondly, sociologic position recognises the need for epistemic practices and cultures to be ‘central to understanding activity,’ (p.182) and finally, a pedagogic position to enable us to understand what learning requires us to do. This pedagogic position is presented as a need to:

Restructure our thinking and acting by locating forms of knowledge and their associated practices in the space of reasons

Reposition ourselves by questioning the constitution of knowledge and practice in relation to their object of activity

Recontextualise and or reconfigure knowledge and practice to achieve new economic, political and social outcomes. (Guile, 2010, p.182)

The tri-fold process of restructure, reposition and recontextualise offers a language to understand the ways in which individuals learn, unlearn past ways of thinking and doing, and enable new situated ways of working to evolve. We argue that this process can be signposted to students by pedagogues to support meta-cognitive understanding, which in turn supports an individual’s tacit knowledge. We move further to argue that pedagogues can consciously deploy strategies which support this trifold process. Strategies which we believe already exist within vocational and practice-based learning programmes of study, as our empirical research indicates.

Methodology

To shed light on the educational strategies which are inherent and which we believe can be made explicit within HE Drama education and wider practical learning degree programmes, we adapted a Kvalian approach to both research design and thematising data. We conducted semi-structured interviews with alumni of a drama programme to understand the ways in which the multiple performance practices within the context of a University Theatre might hang together, be navigated and inform a graduate’s journey from education into the workplace

Aligning with our critical framework, which recognised how knowledge is co-constructed with others in situated settings, our research methods tended towards a localist approach (Alvesson, 2003: 15), recognising the social and situated context of people’s accounts within interviews. Qu and Dumay (2011) recognise the situated nature of the interview process. When analysing data from interviews, they argue that recognising the situated context in which the data was gathered enables additional insights. The semi-structured interview, they argue, is the most useful tool to shed light on local phenomenon. Here the semi-structured interview is conceived as a ‘prepared questioning guided by identified themes in a consistent and systematic manner interposed with probes designed to illicit more elaborate responses’ (Qu & Dumay, 2011, p 246). The interview becomes a conversation, guided by the researcher, with room for improvisation by both parties. In this method, pauses are permitted so the interviewee has breathing space and can break the silence with information of their choice. The semi-structured interview enabled the interviewee to respond ‘in their own terms and in the way that they think and use language.’ (Ibid). The authors cite Kvale’s (1996) typography of questions and critically reflect on good practice to support these localist aims, which we adopted in our methodology.

Particularly relevant for our empirical work which looks at the teaching and learning within a practical university degree programme, taking place across situated and trans-local contexts, Qu and Dumay contend that semi-structured interviews are useful if we are trying to ‘understand the way the interviewees perceive the social world under study.’ (Ibid). We would argue that the pre-established connections between the interviewer and the interviewee i.e., that both have experienced the same creative, social, educational space and previously shared that space as tutor and student, contributes value to the interview process. From a localist position, the roles of interviewer and interviewee are both acknowledged and recognised, allowing for both a structured conversation and a feeling of informality. New roles of researcher and alumni are consciously adopted but there is already a strong sense of familiarity, both of person and place.

Research context

The Bathway Theatre is the University of Greenwich’s dedicated theatre space, based in Woolwich, London. All the Bathway Theatre academic staff have professional performance profiles. The range of HE performance activity that takes place at the theatre can broadly fit into three categories. Firstly, performance pedagogy and learning activity, including but not limited to student performances, lectures, workshops and seminars. Secondly, performance research, including theatre archives, academic conferences and practice-based research explorations (see Ellis et al., 2020; Hockham et al., 2022). Finally, professional performance practice, including associate artists (both long- and short-term) and co-produced and co-led work with members of the local community and wider theatres and organisations. HEs often reframe these three modes of performance activity through the lenses of teaching and learning, research and knowledge exchange as these report to the specific HEI KPIs: Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), Research Excellence Framework (REF), and Knowledge Exchange Framework (KEF). In doing so, however, there is the potential danger for those in HEIs to fail to recognise the interconnected nature of the multiple situated practices within the academy.

Interview sample

We selected a diverse subject group as befits our student cohorts, so included different genders, nationalities, and ethnicities. All participants appeared to have given thought to the questions before the interview and seemed genuinely pleased to discuss their experiences and career journey to date. As intended, a conversation arose within and beyond the scope of the eight questions. Personal reflections were aired by the graduate, often it seemed for the first time. There were affirmations that the experiences had been significantly beneficial and self-actualising.

The data was collected via semi-structured interviews conducted mid-June 2021. The transcribed interviews consist of 31 pages, and extracts of the data are included below. The participants have been named according to their current job title—the technician, the actor, the stage manager, the drama therapist and the director.

Based on a thematic analysis, we have identified three ways in which University Theatre practices operationalise the learning strategies of restructure, reposition and recontextualise. We argue that these strategies are generative and can be explicitly deployed into wider practice-based learning curriculums beyond theatre and performance.

Interview questions

The questions centred on probing their understanding of the relationships, activities and encounters that occurred at the Bathway Theatre and their time as a student on a practical degree programme at the University of Greenwich. This progressed into asking the interviewee to trace their trajectory upon leaving the institution and reflect on how their journey connects to those previous experiences. Having received a Participant Information Sheet and signed a Consent Form, they received these initial questions to ‘look over’ before the interview:

-

(1)

Thinking back, what are the stand-out moments of your time at Bathway and the University of Greenwich?

-

(2)

What types of activity were you involved with at Bathway?

-

(3)

How did your experiences at Greenwich enable new relationships?

-

(4)

What were the challenges you faced when working with others at Bathway?

-

(5)

How did you overcome or meet those challenges?

-

(6)

How did you get to where you are now?

-

(7)

Can you trace the steps of your journey since Greenwich (and during it)?

-

(8)

Are you able to suggest in what ways these were connected?

Interviews were conducted on Microsoft Teams and recorded, lasting approximately 25 min.

Data analysis

Unpacking and analysing the transcripts suggest that the multiplicity of encounters with professional artists, community members, as well as other students and university tutors, within and outside of lesson time, all fed into the students’ career trajectory. The ‘stand out’ activities with which each student was engaged appear to have had an impact that they each critically reflect upon and which they connect to subsequent steps along their trajectory. From the data, we have identified three implicit strategies within the drama curricula at the Bathway theatre, which support students to navigate and recontextualise knowledge. These strategies are then re-deployed by graduates in workplaces which prompts further recontextualisation. In doing so, we have recognised how these implicit strategies can be directly mapped onto Guiles conceptual work and as such, we propose these strategies provide practical ways of working for pedagogues which operationalise Guile’s work.

The three strategies we have shed light on are:

-

1.

To offer multiple different types of performance activities and modes of engagement with different types of people (learner/expert, different cultures, ages, etc.)

-

2.

To provide spaces to fail, enable testing of personal strategies with limited risk

-

3.

To support students in connecting ideas and experiences from the past, across educational experiences of different performance practices and into wider contexts—such as professional work

The paper will discuss each in turn, grouping interview extracts into these clusters. It will demonstrate the ways in which these strategies were encountered within the University Theatre by students and then look to understand how these affected their career trajectory after graduation. In doing so, the paper draws out and demonstrates three student learning processes: practices of communities, recontextualising knowledge and unlearning within an HEI and beyond.

Operationalisation Strategies

A strategy to restructure: to offer multiple different types of performance activities and modes of engagement with different types of people (learner/expert, different cultures, ages, etc.)

Those interviewed recognised and reflected on the ways in which the university theatre housed multiple types of performance-related activity, ranging from academic activity such as lectures, seminars and workshops through the staging of performances, including professional and HEI work. Across the range of performance activity, students reflected on how, in any week or day, they would encounter others working in different ways. The Drama Therapist described a ‘community’ where ‘different types of people came together’ in HEI theatre activity. hey spoke about the ways in which the HEI theatre staff team provided space and support to encounter challenges which occurred when working with different types of people. These challenges they describe as ‘accidental’ in that they were not planned as part of the activity by the pedagogues, but rather, emerged out of the natural differences, viewpoints and ways of working of other individuals. It required students to take on different and unfamiliar perspectives, unlearn cultural assumptions and re-orientate themselves in order to overcome problems. This occurred in group HEI performance activity, where each student practitioner had to navigate multiple viewpoints and nuanced positions. A complex process whereby students recognised increased competence across the degree. They went on to describe how these encounters were ‘very helpful career-wise’ as they allowed the student to navigate differences, noting how these experiences within the HEI theatre gave them the knowledge to adapt to similar challenges and progress within their career. This navigation of difference enabled the student cohort form tight-knit bonds and friendships, which several of the participants spoke to in their interviews as being important to learning when in the HEI, and have continued post-graduation through both personal and professional relationships. The Actor said, ‘… we all came out of it pretty close.… [I am] still in good contact with a lot of the people that I finished with.’ The Stage Manager had a similar story of how her peers now actively form part of her professional network.

In this community, all participants reflected on the ways in which strong bonds of friendship were formed and tested. This was recognised in the context of HEI theatre and performance activity, where groups of students would enter activities with different levels of experience and expertise. There was a recognition that, whilst all were learning to become theatre practitioners, within the umbrella of HEI theatre performance, students were not yet experts. This assemblage of students within student teams was framed by the Director as an ‘intensive’ and potentially stressful experience, as different ways of working and thinking were navigated. This was particularly evident in the Director’s description of devising for HEI theatre and performance. Devising is a method of theatre-making where practitioners start without a written play text. In this process, students were required to probe each other’s thinking and reflect on their own to find solutions. This navigation of different points of view was not always successful and ‘close-knit’ relationships became tested which challenged and developed their interpersonal skills. The student recognised that they had gained knowledge of how to apply these skills within the HEI performance rehearsal process and noted how these stressful experiences gave them the confidence to start their own theatre company. They now deploy the lessons learnt from these experiences in their professional practice both in London and internationally where they work with other professional theatre makers. Whilst the process of devising is similar within these professional spaces to that of the HEI theatre, those in the professional space bring with them the knowledge learnt from their HEI experience and training providing a slightly different set of challenges to navigate as practitioners ask constructive and informed questions. The Director noting how the experience of the HEI supported their ability to navigate these professional spaces is a clear example of recontextualisation from the HEI Theatre to wider theatre practices. The Director went on to start her own theatre company in London, then worked in her home country of Holland, and then became employed as a full-time director in a major European Theatre.

This section has recognised how students in HEI encounter difference within HEI theatre activity. Here difference has been considered as other points of view, ways of working and standpoints which were historically formed from past activities and experience. Through a student’s HEI trajectory, encountering differences this way enables students to restructure their way of working to enable other voices to be heard. This in turn enables a restructuring of how they might think and approach a task and create new connections between past experience and current activity. In this process past assumptions about ways of working are unlearnt as the default norm. A restructuring process which individuals can use in contexts beyond the classroom and in the world of work.

A strategy to reposition knowledge: to provide spaces to fail, enable testing of personal strategies with limited risk

The ways in which an individual’s confidence grew across their degree trajectory was evidenced by the Drama Therapist who spoke about the difficulty of speaking within the learning community:

…speaking up within a group setting…. I kind of figured that … I'm gonna have to be, you know, bold and .. so, I thought yeah, try it...I started off small and …developed coping strategies and .. built the courage up and then transferred those skills over to other settings.

This was particularly relevant as the Drama Therapist declared she was lacking social confidence at the start of her studies, when she would usually let others speak up. This was something she wanted to change. In the extract above we can see this change was gradual, over the course of their studies, using the degree to try out new approaches. Positions of anxiety were stoked by feelings of getting things wrong, failing or not speaking coherently. The HEI offered space and time for them to develop strategies to voice opinions, coached through feedback by pedagogues. Through this coaching, the student learnt that their voice was important and had something to offer, which built confidence, with the perception of failure shifting from, ‘if I say something I might get it wrong’ to, ‘I won’t learn if I don’t speak up.’ This strategy they have then taken to work in wider contexts, such as work.

Using failure as a learning tool is highlighted by the Technician who recognised how they would approach tasks through trial and error asking, ‘if something went wrong, how could it be made better.’ A clear example of ‘forward gazing’ (Stretch & Roehrig, 2021, p.125). This willingness to use failure as a tool to learn gave the Technician confidence to respond to opportunities as they arose. This saw the student become involved in activities which at first felt ‘scary’ to them, as they were scared to fail, yet recognized that if things went wrong, they had the support structures in place to rectify them. In addition, the Technician went on to talk about how he learned the importance of asking questions, recognising that not knowing did not signpost failure, but rather a willingness to learn.

A commonality between the interviewees was taking risks by seizing opportunities, be this in extracurricular activities or within the taught lessons. The Technician approached their university experience through the mantra of ‘I have nothing to lose’. They recognised the HEI programme as a space to take risks, by trying something out even if they are not sure of the immediate or longer-term benefit. It is important to note that due to their socio-economic status, most of this university student cohort also have retail jobs or bar work to support their studies. Therefore, squeezing in extra demands on their time magnifies the risk of overload or burnout. This was seen by the interviewees as another layer of risk worth taking.

The Stage Manager reflected how she ‘just tried to do as much as I could in uni…to mean that I had the experience to put on my CV’. This included a placement at an arts centre, performing in another year group’s assessed public performance, and becoming a member of the university’s Drama student company at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Within all these activities, and perhaps as a coping mechanism, the Stage Manager developed another repositioning strategy for personal work practices. She commented that the biggest challenge in the university learning environment was when she found herself with less motivated peers in a group project, those who ‘didn’t work as hard as they could’. In response, when unable to choose her own group members, she would try to motivate those around her, to ‘encourage them to meet up more…to excite them about the project’ and help colleagues to find their own way of being inspired by the task at hand. The Stage Manager noted that this strategy was only successful ‘sometimes’ but again this is an example of testing a personally found method that would re-apply in professional work settings.

These ‘personalised’ experiences of failure (see Lattacher & Wdowiak, 2020), outlined in this section, demonstrate the ways knowledge is repositioned by individuals, allowing learners to question past knowledge and experience and reposition it in relation to the situated activity they are trying to achieve. Enabling space for failure within curricula a strategy to operationalise the concept of ‘repositioning.’

A strategy to recontextualise: to support students in connecting ideas and experience from the past, across educational experience of different performance practices and into wider contexts—such as professional work

Graduates also reflected on how exposure to professional practices during their study altered the ways in which they worked on the degree programme, forming new ways of working and doing. This can be seen as another process of recontextualisation.

The Technician offered three ways in which they were exposed to professional practice within their degree programme: placement, visiting artists and employment. They spoke to the ways in which the placement, which took place in their second year ‘opened their eyes’ to the work involved in sustaining a career in the industry. Working for a short period in a professional theatre environment exposed the areas of knowledge which still needed developing in their third year, whilst affirming the knowledge they had already gained.

…being around those people really opened my eyes. I mean, I've, I've gotta work hard. This isn't… I can't just sort of flounder about…I've got to really commit to the craft and…, it changed my whole third year perspective.

The extract exposes the way in which the Technician altered their attitude towards their final year of study, re-positioning their perspective to learning. It offers an example of the way in which the Technician recontextualised knowledge from their placement experience, work ethic, skills and craft back into their final year of study, re-orientating their position within their learning journey. At the same time, it enabled the student to recognise variations of methods and practices based on a practitioner’s approach or company style. These differences exposed the multiple professional performance possibilities, enabling the student to orientate towards future new ways of working.

The Technician also spoke about being offered paid work as a student production assistant, where they were employed to support student productions, events and external hires within the theatre building. The range of activity they worked on exposed the students to different ways of working. The Technician reflected on how different companies responded to different situated challenges or transferring into the university theatre space which required setting up and performing in a single day and spoke of the different tensions which arose out of this touring activity, compared to that of a longer HEI performance process. They also reflected on the work with different community groups, who had different cultural identities to their own. This process of reflection, which they recognised was embedded within the programme module design, enabled the student to recontextualise knowledge and identify personal ways of working. They began to create a professional persona.

The Technician’s approach whilst studying within the HEI was to encounter as many ways as possible of working because they were unsure what they wanted to do post-degree. A similar set of observations can be seen with the Director and the Stage Manager. The Actor and Drama Therapist, however, knew they wanted to move towards these job roles at the beginning of their HEI journey. As such they chose what they encountered. For example, the Actor said a ‘big highlight’ was performing alongside professional actors and directors in the local Book Festival, an initiative facilitated by the University Drama and Creative Writing programmes to showcase new theatre playwrights. This was found to be a ‘really good experience’ that embedded employability strengths.

Likewise, the Drama Therapist took a placement with a local theatre that employed a drama therapist, whom they shadowed for a year. This provided the required necessary work experience in order to go on to do a masters in drama therapy. She now has her own clinical practice and is successfully building her client base. This strategic plotted trajectory aligned with the scaffolded approach required by their chosen career. The student was able to identify how the placement reorientated their understanding of the drama therapy work practice, gaining knowledge which was recontextualised in their master’s programme before once again being recontextualised in the specific, daily, drama therapy practice.

The programme also built in opportunities of working with theatre professionals in different modules. The Actor spoke to the ways in which they learnt specific applied theatre and theatre education methods with a practitioner who pioneered the way in their respective field. Whilst at the time, the Actor recognised the set of practices as enjoyable, they were unsure why this might be useful for their future career as an actor. When reflecting on their career trajectory, however, they recognised how their first acting job was in a Theatre in Education company, which toured internationally. Having now gained a portfolio of acting roles, Theatre in Education still provides lucrative income.

From the examples outlined above, we can see how students recognise and recontextualise knowledge in their HE trajectory in three ways. The first is that some students deliberately expose themselves to multiple ways of working in order to understand the types of work they might want to encounter beyond the HEI. The second is that some students are aware of what they want to do post-HE and therefore plot a trajectory through the programme to provide them with the experience and knowledge to attain their goal. The final way appears as a nuanced position between the first two points. Students who are aware of what they want to do might encounter practices which they enjoy but are unsure how they might later recontextualise in their later work practice. This realisation only occurs when opportunities post-university arise, where students can then identify past relevant experience and re-contextualise them in ways that are surprising for the individuals. In doing so, learners are able to re-structure their understanding of what they thought the work might be, unlearning rigid definitions of what performance is. With narrow definitions created from past education, popular entertainment and social media. Whilst data in this pilot suggests students are connecting ideas from past educational experiences, earlier work recognises students also connect ideas from outside of the classroom to support the process of recontextualising (See Hockham, 2022: 174–191).

Conclusion

Our empirical research has shed light on three implicit pedagogy and learning strategies which we recognise as aligning to Guile’s conceptual topology of restructure, reposition and recontextualise.

Our three teaching and learning strategies make the case:

-

1)

To offer multiple different types of performance activities and modes of engagement with different types of people (novice/expert, different cultures, ages, etc.).

-

2)

To provide spaces to fail, enable testing of personal strategies with limited risk.

-

3)

To support students in connecting ideas and experiences from the past, across educational experiences of different performance practices and into wider contexts—such as professional work.

In doing so we argue that these strategies can be seen to operationalise this conceptual work in a similar way to the relationship between Vygotsky’s ZPD and Wood, Bruner and Ross’ notion of scaffolding. Further, by making these pedagogic strategies explicit, we argue that pedagogues can use them to support students to make use of past knowledge and deploy these experiences in the learning environments within Higher Education. Further, these strategies can be redeployed by individuals in wider work settings, recontextualising the learning from education into work.

Whilst we have specifically focused on the learning and pedagogy within a practical drama programme within a London university theatre, we recognise these strategies as generalizable. We argue these are able to be used within wider fields of knowledge beyond theatre and performance in the UK and potentially in international learning settings. Our approach also suggests wider consequences. If students are able to recontextualise past diverse experiences into educational contexts, then these strategies may potentially support a diverse student body to succeed within practical subject areas. This research cannot say this with certainty, given the limited data within this pilot, but this appears a further avenue of exploration in future work.

We argue that students who are studying a practical degree will benefit from an environment where students are exposed to multiple types of people and ways of working, encouraged to take risks and not be afraid of failure and create connections across and beyond their degree to forge personal ways of working. In doing so, those graduates, whatever path they choose, will have the skills to recontextualise learnt knowledge within the world of work and be able to collaborate with others in global contexts.

References

Alvesson, M. (2003). Beyond neopositivists, romantics and localists: A reflective approach to interviews in organizational research. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 13–33.

Dreier, O. (1999). Personal trajectories of participation across contexts of social practice. Outlines Critical Social Studies, 1, 5–32.

Dreier, O. (2008). Psychotherapy in everyday life. Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, T., et al. (2020). Becoming civic centred – A case study of the University of Greenwich’s Bathway Theatre based in Woolwich. Studies in Theatre and Performance. Routledge, 40(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2020.1807211

Guile, D. (2010). The learning challenge of the knowledge economy. Sense Publishers.

Hockham, D., Campbell, J., Chambers, A., Franklin, P., Pollard, I., Reynolds, T., & Ruddock, S. (2022). Let our legacy continue: beginning an archival journey a creative essay of the digital co-creation and hybrid dissemination of Windrush Oral Histories at the University of Greenwich’s Stephen Lawrence Gallery. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 27(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2022.2060733

Hockham, D. (2022). What are the implications for HEI Pedagogy and learning when production and technical theatre practices are re-orientated as practices of scenography? Investigating technical theatre training, in higher education institutions (HEI) levels 4-6 within the United Kingdom (UK). Doctoral thesis (Ph.D). UCL (University College London). https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10152859/

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning. Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Koschmann, T., Kuutti, K., & Hickman, L. (2009). The concept of breakdown in Heidegger, Leont’ev, and Dewey and its implications for education. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 5(1), 25–41.

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage.

Lattacher, W., & Wdowiak, M.A. (2020). Entrepreneurial learning from failure. A systematic review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2019-0085/full/html

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situate learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 4(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.4.2.191_1

Qu, S., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, 8, 238–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/11766091111162070

Schechner, R. (2013). ‘Performance studies: An introduction’, in Performance studies: An introduction (3rd ed.). Routeldge.

Stretch, E., & Roehrig, G. (2021). Framing failure: Leveraging uncertainty to launch creativity in STEM education. International Journal of Learning and Teaching, 7(2), 123–133.

Vygotsky, L. (1987). The collected works of L S Vygotsky: Problems of general psychology (Vol. 1). Plenum Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hockham, D., Wallis, J. Operationalising the concept of recontextualisation: leveraging pedagogy and learning strategies in higher education practical courses. High Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01136-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01136-3