Abstract

The collection of data on values through instruments such as the World Values Survey has focused attention on two opposing but inter-related trends, namely the combination of substantial cultural change in many countries and the persistence of distinctive traditional values. This reflects the interplay between social changes associated with modernisation and globalisation—including increased global trade and the rise of global popular culture—with traditional values country-specific systems. In this paper, we introduce a focus on another potentially important source of change, that of widening higher education participation and attainment, and the extent to which self-reported values differ between university graduates and non-graduates. We investigated this question using data from the most recent collection of the World Values Survey (2017–2020) for six core values—family, friends, leisure, work, politics, and religion—and tested for the influence of higher education attainment on the perceived “importance” of each value and the extent to which this influence differs across values and in gender, generation and country grouping sub-samples. We find evidence for consistent effects in most contexts, with no statistical differences between graduates on non-graduates in relation to the propensity to view family and work as important, statistically significant positive effects on the propensity of graduates to view friends, leisure, and politics as important, and a significant negative effect in relation to religion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rising participation in higher education is a global phenomenon, with a recent UNESCO report noting that “in the first decade of the 2000s, participation rates in higher education institutions increased by 10 percentage points or more in many regions like Europe, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean” (UNESCO, 2020: p.24). This follows the documented global expansion in university systems since World War II, resulting in a shift from “elite” to “mass” rates of participation and attainment in most developed countries, eventually approaching near “universal” levels, where up to 50% of a population have received degrees (Trow, 1974, 2007). Statistics from the OECD group for 2020 indicate that such levels of attainment are now present among younger cohorts in those countries, with 45% of 25- to 34-year-olds in the OECD having obtained a tertiary qualification, the largest component of which includes those whose highest degree is a bachelor’s qualification (OECD, 2021).

Higher education attainment shapes societies in many ways. University graduates earn higher wages than non-graduates, even if recent evidence suggests that the earning premium for graduates is declining (for the UK, see: Boero et al., 2021). In addition, graduates have traditionally experienced better outcomes in terms of health, longevity and family formation (Hartog and Oosterbeek, 1998). Higher education attainment has also been accompanied by major societal changes, including significant shifts such as increased female participation in the labour force (OECD, 2019).

Given the increase in higher education participation and attainment, it seems plausible to consider higher education as an important factor in either shaping value sets across countries. However, the study of cross-country values over the past three decades has focused largely on the impact of other major drivers or change in challenging accepted norms and customs at the national level. These include both economic and cultural processes operating through common vectors: global trade and travel; international economic and political institutions and groupings; and global mass media and communications networks (Inglehart and Baker, 2000).

Two views on the impact of these forces on national culture are largely characterised by the observed convergence in national cultural norms and values resulting from them: modernisation, a process by which traditional values are replaced with “modern” values (Yeganeh, 2017); and globalisation, whereby standardisation in industrial, cultural and educational structures results in a homogenous transnational culture (Ritzer, 1996). A common feature of these two notions is the increase in “interconnectedness” of national cultures in the post-Cold War global setting (Buell, 1994).

Consequently, standard approaches to discussing national cultures, such as cultural dimensions approaches, are less likely to provide a coherent understanding of national culture (Yeganeh, 2017). Focus has instead shifted to an analysis of the influence of globalist/modernist forces on national cultural values.

Inglehart and Baker (2000) nominate competing effects that capture outcomes from this process, namely, convergence, whereby values across countries and groups become more similar over time and persistence, whereby traditional values are maintained. Data on values have been collected at the country-level through the World Values Survey (WVS), a global survey that has tracked changes in reported values since 1981 and is currently in its Wave 7 (2017–2020) collection (Haerpfer et al., 2020). Inglehart and Baker (2000) analysed data from the 1995–1998 wave of the WVS to determine the extent to which economic development results in changes in value orientations. This primarily reflects global convergence in values. They describe a traditional to secular-rational orientation, where due to economic and technological integration associated with modernisation, a convergence of values takes place towards the secular-rational, including a less central role for religious or national societal beliefs in value expression. In a second value orientation, survival to self-expression, populations begin to emphasise values and preferences which favour the consumptive and exploratory (self-expression) rather than those predominantly associated with survival and protection. They found evidence for a combination of effects, demonstrating that “massive cultural change and the persistence of distinctive traditional values” was evident in the WVS data, as social changes associated with modernisation were moderated or checked by traditional institutions and practices, making country-specific effects path dependent on individual country histories—much of them shared between groups of countries with common geographical, cultural and religious backgrounds.

Recently, this analysis has been extended to focus on longitudinal trends in the WVS. For instance, Matei and Abrudan (2018) examined trends in WVS respondents’ assessments of the importance of six broad values: family, friends, leisure, work, politics and religion, and found that over the multi-year collection horizon for the WVS, changes in respondents’ views on values at the national level occurred more quickly in countries undergoing major sustained changes, principally economic ones.

In this paper, we focus on higher education attainment as a potentially important influence on values, focusing on evidence from the WVS on respondents’ assessed importance of the six WVS values examined in Matei and Abrudan (2018). Specifically, we examined the extent to which the importance placed on these values differed between university graduates and non-graduates in the most recent WVS collection (2017 to 2020), both in a main sample and sub-samples generated for gender, generational and country grouping.

Higher education and values

It is not difficult to view higher education attainment as a consequential force for both globalisation and modernisation. As the OECD (2019) points out:

Higher education plays an integral role in globalisation and in the knowledge economy, as it facilitates the flow of people, ideas and knowledge across countries. Higher education therefore acts as an engine for ‘brain circulation’ between countries. (p.36)

This is a natural extension of higher education’s traditional focus on the acquisition, retention and transmission of knowledge irrespective of national borders (Marginson and van der Wende, 2007), with this role amplified through the rise of global travel and communications networks, the cross-border movements of researchers and students and the emergence of the bachelor’s degree as an entry level qualification for many occupations. This has been accompanied by the emergence of high participation systems (HPS) in higher education, which have extended the opportunity for, and increased levels of, attainment and its benefits across society, with the diffusion of benefits dependent on social consensus and policy commitment around the importance of social equality and mobility (Marginson, 2016).

The latter point is critical as the emerging centrality of education to improved social outcomes is recognised by those who have experienced its benefits. A recent study using WVS data by Feldmann (2020) found that respondents with higher levels of educational attainment were more likely to regard inadequate education as the most serious problem in the world, while Marginson (2018) finds support for Trow’s (1973) prediction that the expansion in higher education places would be led by social demand rather than government fiat.

How might higher education attainment influence the reported importance placed on the six values tracked by the WVS? The immediate answer is that the influence is bi-directional as stated “values” reflect not only experiences at university, but also encompass key influences on higher education. Although they comprise a sizeable minority in younger cohorts, higher education graduates are still characterised as belonging to a relatively advantaged section of their community across countries (Atherton et al., 2016). Marginson (2016) points out that:

In contemporary societies, those desires [for betterment], particularly the hopes of parents for children, have become primarily focused on formal education, which is seen as the privileged pathway to professional work. Family ambitions have no ultimate limiting factor and feed on themselves. Over time the social demand for higher education accumulates and tends towards the universal, as Trow predicted it would, and higher education provision becomes large, growing and increasingly ubiquitous. (pp. 414-415)

An extension of this argument is that higher education participation facilitates social reproduction, thus entrenching traditional systems of values in countries, with parents from advantaged backgrounds provide resources in the form of monetary, social and cultural capital to facilitate their children’s transition into post-compulsory education (Bourdieu, 1986).

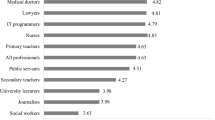

This mechanism applies to other WVS values such as work, where family background is a key influence in relation to education and career choice, as outlined in the ecological model of Bronfenbrenner (1979). Thus, professionally qualified parents instil value sets that replicate their experiences and facilitate inter-generational transfers of privilege. The persistent importance attached to the family value in the WVS is testament to this influence, with around 91.7% of Wave 7 WVS respondents regarded family as being important.

Alternatively, the position of universities at the forefront of changes associated with globalisation, modernity and the emergence of the global market economy also produces graduates who are more likely to challenge traditional norms. In many settings, higher education is especially transformative, as young adults leave home to live on or around campuses, elevating the importance of friendships and associations—both temporary and more permanent—during their formative years (Gravett and Winstone, 2020; Picton et al., 2018; Brooks, 2007), ostensibly making friendship more important to higher education graduates and raising the importance of the value of friends to graduates.

After family, work is the WVS value most likely to be regarded as important. This is tied to the centrality of work to life choices, both in terms of earnings and professional or employment satisfaction. Higher education graduates see better outcomes on both these measures than non-graduates (high school and technical graduates), an effect described in both the human capital (Becker, 1964) and signalling (Spence, 1973) theories of earnings in economics and constructivist theories of education in sociology (Bourdieu, 1986), and borne out in empirical work (Crivellaro, 2016; Elias & Purcell, 2004; Wilkins, 2015). Job satisfaction also tends to be higher among higher education graduates compared to non-graduates (Rosenbaum & Rosenbaum, 2016).

Perceptions of the value attributed to leisure tend to be dichotomous, given the trade-off between it and work inherent in its common definition, for instance:

…all activities that we cannot pay somebody else to do for us and we do not really have to do at all if we do not wish to. (Burda et al., 2007, p. 1)

Leisure thus encompasses activities other than work and personal care (core non-work responsibilities), but with a potential for overlap between these three categories. While there has been relatively little work on the relationship between leisure preferences and higher education attainment, the OECD (2009, p.38) examined cross-country evidence on the residual of paid work (a measure of leisure) and net national income, finding a positive relationship between the two, suggesting that leisure is a normal good—one whose demand rises with income. Presumably, this also applies to personal or household income, subject to the time constraints associated with higher earnings (i.e. increased hours). Given this, we hypothesise that higher education graduates will have increased preferences for leisure compared to non-graduates.

The impact of higher education participation on attitudes to politics, political activism and interest is well documented, with graduates more likely to be politically engaged than non-graduates (see for instance, Hillygus, 2005), although recent studies have explored the extent to which this is attributable to higher education institutions or is intrinsic to the broader social backgrounds and life experiences of graduates (Kam and Palmer, 2008; Perrin and Gillis, 2019). This latter point raises the question as to the uniqueness of higher education in modern society in shaping political values and opinions. Higher levels of education are associated with greater degrees of interest in broader value discussions, such as those relating to the environment (Gifford and Nilsson, 2014). More generally, education attainment is a key factor in voting patterns and related issues such as trust in political processes (Nie et al., 1996).

In relation to religion, higher education attainment is associated with a reduced level of religious belief and a preference for the secularisation of institutions, although not necessarily religious observance—seemingly contradictory outcomes that Glaeser and Sacerdote (2008) attribute to the tendency of education to displace religious belief with secular humanism while at the same time raising virtually all measures of social connection. This is often specific to country grouping. For instance, the Pew Research Centre’s 2016 study of higher education and religion found that in the USA and France, self-described atheists were more likely to have post-secondary qualifications than those citing a religion, whereas no statistically significant difference was observed in many other developed countries (Hackett et al., 2016).

Across the six WVS values, the influence of higher education may be mediated by a variety of associated factors, many of which influence higher education participation itself. These include individual factors, such as gender, age/generation and family educational background, class group membership and household income (in the context of pro-environmental concerns and behaviour, see Gifford and Nilsson, 2014), as well as the social and national context factors identified by Inglehart and Baker (2000) and others.

Methodology: data and method

This study sought to examine differences between higher education graduates and non-graduates in their stated importance of the six WVS values, both in a cross-country sample and important sub-sample contexts: gender, generation and country grouping associated with stage of economic development or shared cultural values.

We analysed data from the Wave 7 of the WVS on the importance respondents place on various core values. The study included response sets from 48 of 49 countries (listed in Table 1) who reported back for Wave 7. We omitted Guatemala, as the country’s response file was missing data on questions pertaining to mother’s and father’s educational background (Questions Q277r and Q278R).

The measures of values examined corresponded to WVS respondent views on six values from the survey, drawn from answers to the first question in the “Core Questionnaire” of the WVS:

For each of the following, indicate how important it is in your life. Would you say it is…

(Very important/Rather important/Not very important/Not at all important) –

-

Q1 Family

-

Q2 Friends

-

Q3 Leisure time

-

Q4 Politics

-

Q5 Work

-

Q6 Religion

From this response set, we constructed dependent categorical variables for each of the six listed values (family to religion), with “important” being defined as whether a respondent found the value to be either “very important” or “rather important”, with responses coded as “1” in either instance or “0” for any other response.

From the WVS, a set of explanatory indicators was constructed to explain variations in the categorical dependent variable. These are the following:

-

Gender: 1 = Female; 0 = Male. (The count in the “Other” option was too low to include it in the analysis).

-

Ln (Age): Natural Log of Age (years). (A continuous variable).

-

Higher Education: 1 = higher education; 0 = otherwise.

-

Marital Status: Married (base, omitted in the analysis); Living Together; Divorced; Separated; Widowed; Single.

-

Children: Number of children. Continuous variable.

-

Non-migrant: 1 = born in country; 0 = otherwise.

-

Mother Higher Education Background: 1 = mother has higher education degree; 0 = otherwise.

-

Father Higher Education Background: 1 = father has higher education degree; 0 = otherwise.

-

Employed: 1 = person is working; 0 = otherwise.

-

Work Sector: Public Sector (base); Private Industry; Private Non-Profit.

-

Social Class: Self-nominated—Upper (base); Upper Middle; Lower Middle; Working; Lower.

-

Income Level: Self-nominated—Upper (base); Medium; Low.

-

Religious Belief: 1 = person nominates a religion; 0 = otherwise.

In addition, data on two country groupings were included from other sources.

Data on per capita gross domestic product (GDP per capita) was sourced from the online CIA World Factbook (Central Intelligence Agency, 2021), for the year 2018. Countries were classified as follows:

-

GDP per capita: High (> US$25,000) (base); Middle (US$10,000–25,000); Low (< US$10,000).

Countries were classified according to the cultural categories outlined in the Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map (2020) in Haerpfer et al. (2020):

-

Inglehart-Welzel categories: Classification of countries in the sample was as follows:

In total, the main sample sourced from the Wave 7 collection of the WVS included records from 41,146 respondents across the 48 countries, of whom 14,399 (35%) had attained a higher education degree.

In the first instance, we examined reported outcomes for each of the six values. We then constructed an explanatory model for each value. As the dependent variable was binary, we used a logistic regression method to explain the probability of respondents nominating a value as important, using the same set of independent variables to explain the odds of respondents nominating a given value as being important. Each model was estimated using the main sample (N = 41,146), with effects reported as odds ratios. After this, we analysed sub-samples selected along the lines of gender, generation and country grouping (GDP per capita and Inglehart-Welzel category).

The importance of values in the WVS

In the first instance, we examined patterns of responses across the six values (percentage and ranking) for the main sample. As reported in Table 2, responses generated a wide dispersion in the percentage of respondents nominating values as “important”, ranging from near universal acceptance of the statement for family (99.3%) to only minority support for politics (46.7%).

The sub-sample for higher education graduates indicated that preferences among graduates tended to broadly track the patterns seen in the total population, but with noticeable differences. For instance, in relation to friends, 91.1% of graduates cited this value as being important compared to 87.3% of the total population, with other differences apparent (e.g., Politics: 50.4% vs 46.7%). However, the ranking of values between graduates, non-graduates and indeed the entire sample was identical: family, work, friends, leisure, religion and politics.

In addition, value preferences were examined across the sub-samples for gender, generation and country grouping measures. In these cases, differences did emerge.

For instance, in the gender sub-samples, differences were observed between females and males, especially in regard to politics. However, the ordering of values was identical to that seen in the main sample in both instances.

Differences across the generations were most pronounced at either end of the age spectrum, as expected, reflecting the age gap and the natural drift in concerns over the life-cycle. For instance, only 68.7% of the largely retired Post-War generation nominated work as being important, compared with 94.6% of Millennials. An examination of the ordering of values indicates a broad split between the generations, with the younger generations, Generation X and Millennials, having the same ordering of values, one identical to the main sample, the young boomers (Boomers II) attached greater importance to friends than work, albeit marginally, and the two older generations, Boomers and Post-War, placing a greater emphasis on leisure than work.

Finally, an analysis using the two country groupings, the GDP per capita and Inglehart-Welzel category variables, allowed for the classification of respondents at the super-national level. Country income levels (proxied by GDP per capita) appear to be correlated with two effects also observed in relation to higher education attainment: an increasing importance attributed to friends as income levels increased—with this value ranked second for high GDP per capita countries compared to fourth for low GDP per capita countries; and a reduced importance attached to religion, ranked fifth among respondents in the high and middle low GDP per capita groups compared to third in low GDP per capita groups. A similar pattern is seen in a country classification using the Inglehart-Welzel categories, with the importance attached to friends and religion differing across countries.

Findings on the determinants of value preferences

The analysis of the main sample for each WVS value was conducted using logistic regression, with odds ratios and overall model statistics reported in Table 3. For categorical variables, the null hypothesis is that of no statistically significant difference between categories in the odds of respondents regarding a value as “important”, corresponding to an odds ratio of 1.000. For example, in the case of the higher education variable, a failure to reject the null hypothesis—or similarly, a statistically significant odds ratio of 1.000—indicates no difference between graduates and non-graduates in their odds of nominating a value as important. Alternatively, a statistically significant estimate of the odds ratio above (below) 1.000 indicates that graduates are more (less) likely to do so.

Family

Family was rated as important by a near totality of respondents, with few noticeable differences across the sub-samples. There was no statistically significant effect observed at the 0.05 level attributable to higher education attainment relative to non-attainment (higher education: 1.138 [odds ratio], p > 0.1).

A highly significant gender effect was observed, with women 73 per cent more likely to view family as being an important value than men (gender: 1.730, p < 0.01). In addition, a significant effect was present in relation to age (Ln (age): 0.342, p < 0.01), indicating a declining propensity to view Family as important with respondent age. Somewhat unsurprisingly, marital status affected the value attached to family relationships. In comparison to married respondents, those living together (0.579, p < 0.05), divorced (0.294, p < 0.01), separated (0.233, p < 0.01) or single (0.313, p < 0.01) were substantially less likely to nominate family as being important. Household size and composition was also significant, as proxied by the children variable (1/150, p < 0.05). Social class (household), income level effects and GDP per capita were not significant in explaining preferences for family as a value. In fact, there were no effects observed for social class across all values, although income effects operating at the micro- (household) or macro-economic (GDP per capita) levels were observed. Religious belief (1.816, p < 0.01) had a significant and positive effect on respondents’ views. There were limited effects seen across the Inglehart-Welzel category variables, although one exception was the Confucian country category (1.891, p < 0.01). This result was not surprising as Confucian teaching places a special emphasis on the importance of family as the most basic unit of society (Yi, 2021).

Friends

In the main sample, the friends value had the strongest effect associated with higher education attainment (higher education: 1.402, p < 0.01), with graduates 40 per cent more likely to nominate friends as an important value compared to the entire sample. Single respondents were more likely to value friendships compared with married people (single: 1.146, p < 0.01), while respondents in non-married relationships and those with children were less likely to nominate it as being important (living together: 0.734, p < 0.01; children: 0.967, p < 0.01). Employment effects were observed, notably a reduced likelihood among those in the private sector (private industry: 0.846, p < 0.01) compared to those in the public or private non-profit sectors. No meaningful household income level effects were observed. Religious belief had a positive influence (religious belief: 1.115, p < 0.05), although this was substantially weaker than that seen in the family model. A strong GDP per capita effect was observed, whereby in contrast to the findings for family, those from low (0.638, p < 0.01) and medium (0.643, p < 0.01) countries were less likely to nominate friends as being important than from high GDP per capita countries (the control group). Several Inglehart-Welzel category effects were observed, with respondents in Latin America (0.338, p < 0.01) and Orthodox Europe (0.621, p < 0.01) being less likely to view friends as important, relative to the omitted category (English), while respondents in the Confucian (1.327, p < 0.01) and Protestant Europe category (respondents from Germany only) (Protestant Europe: 2.998, p < 0.01) substantially more likely to do so.

Leisure

The influence of higher education attainment on views on leisure as a value was significant and positive (higher education: 1.381, p < 0.01), with an effect comparable to that seen in the friends model. There was no statistically significant effect associated with gender (1.122, p < 0.01), with women more likely to nominate leisure as important, and a statistically significant, but muted effect associated with age (Ln (age): 0.901, p < 0.05). This latter effect suggests that the propensity to value leisure as important declines with age, where other control variables are present in the model. In comparison with family and friends, marital status had less influence on leisure’s perceived value, with non-married partnered respondents (living together: 1.141, p < 0.05) and single respondents (single: 1.093, p < 0.05) both reporting more positive positions in relation to leisure than the control group (married). Non-migrant status had a significant and positive influence, one broadly comparable to that associated with higher education attainment (non-migrant: 1.219, p < 0.01) and in direct contrast to its statistical insignificance in models of the first two values. Employment had a strong and statistically significant positive influence on leisure preference (employed: 1.232, p < 0.01), with private sector employment moderating this effect (private industry: 0.833, p < 0.01). A GDP per capita effect was observed, with respondents in low (0.275, p < 0.01) and medium (0.449, p < 0.01) income countries less likely to cite leisure as being important in comparison with those from high GDP per capita countries. No effect was present for the religious belief variable. The Inglehart-Welzel category variables showed that respondents in Confucian (0.689, p < 0.01) and Orthodox Europe (0.628, p < 0.01) countries were substantially less likely to attach importance to leisure compared with those from the omitted (English-Speaking) category. The strongly positive effect associated with Catholic Europe (2.022, p < 0.01) applies to the only country in the category, Andorra.

Politics

Politics was the value respondents were least likely to nominate as important. As was the case with friends and leisure, the higher education variable was positive and significant (higher education: 1.220, p < 0.01), indicating substantially higher odds of university graduates nominating political issues as being as important, with the effect being somewhat less pronounced, although still significant at the 0.01 level. The estimated odds ratio for gender (0.813, p < 0.01) indicates that female respondents were less likely to share this view. Although a significant age effect was observed, the odds ratio (Ln (age): 1.187, p < 0.01) indicated a very limited trend across the age spectrum. Marital status encompassed two significant effects, with respondents who were in relationships self-classified as living together (0.852, p < 0.01) or separated (0.856, p < 0.05), less likely to view politics as important in their value sets. Non-migrant, or native born, respondents were more likely to be engaged with political values than migrant respondents (non-migrant: 1.276, p < 0.01). Parental educational background was marginally statistically significant, although this depended on the gender of parents, with a statistically significant effect only observed among respondents whose fathers had higher education degrees (father HE: 1.090, p < 0.05).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, employment and household income status affected the probability of respondents nominating politics as important. Those in employment were less likely to nominate politics as important (employed: 0.932, p < 0.1), with a stronger effect demonstrated among those in the public sector given the relative reduced likelihood of private sector employees to nominate politics as an important value (private industry: 0.882, p < 0.01; private non-profit: 0.814, p < 0.01). While no effects were determined in relation to social class, relative effects attributable to income level were observed, with respondents from low (0.899, p < 0.05) and medium (0.852, p < 0.01) income level households less likely than those from high-income households (the omitted category) to describe politics in their country as being important to them. As was the case with leisure, no effect was present in relation to the religious belief variable.

In terms of country effects, respondents from medium GDP per capita countries were much less likely than those from high GDP per capita to nominate politics as being important to them. The inclusion of the Inglehart-Welzel category variables indicated that all groups, except for the Protestant Europe (Germany) (higher probability) and Confucian (statistically insignificant) groups, had lower probabilities of their respondents nominating politics as important compared to the omitted English-Speaking category. This may be in part due to the timing of the survey in 2017, coming after the 2016 Brexit vote in the UK, and subsequent political shocks through Europe, and the US presidential election in 2016 (Inglehart and Norris, 2016).

Work

After family, work was the value second most nominated as important by respondents, at around 91.6% of the main sample. No statistically significant effect was observed in relation to higher education, although an effect was seen for maternal higher education status (mother HE: 0.740, p < 0.01). The gender variable was also statistically insignificant in explaining patterns of work importance. The Ln (age) variable had a significant parameter estimate (0.382, p < 0.01), somewhat capturing the effect observed in the data reported by generation in Table 1, which showed a marked divergence in attachment to work across the generations due to their position in the employment life-cycle, with just 68.7% of members of the Post-War generation nominating work as being important, compared to 94.6% of Millennials. The marital status variables were insignificant with exception of widowed (0.680, p < 0.01), with the other household composition variable, children, also having a statistically significant effect (children: 1.093, p < 0.01).

The strongest effect observed was in regard to employment status, with those in employment much more likely to nominate work as important (employed: 3.716, p < 0.01), although there was no observed difference by sector of employment The social class and income level variables were insignificant in explaining trends in this value.

Three other prominent effects were identified. Respondents from non-migrant or native-born backgrounds were more likely to exhibit a strong work preference (non-migrant: 1.216, p < 0.01). Similarly, respondents with religious beliefs were more likely to do so (religious belief: 1.317, p < 0.01). Finally, country effects were observed, with respondents from low and medium GDP per capita countries more likely to nominate work as being important compared to those from high GDP per capita countries (low: 1.701, p < 0.01; medium: 1.451, p < 0.01). The Inglehart-Welzel category variables were all highly significant and uniformly indicated a greater probability of respondents nominating work as important compared with those in the omitted English-Speaking category.

Religion

Religion was rated as important by 70.3% of respondents, ranking fifth in the main sample. The most important variable in explaining religious preference as a value was stated religious belief (religious belief: 7.685, p < 0.01).

Higher education graduates were likely to be less religious (higher education: 0.817, p < 0.01). The negative impact of higher education attainment on religious belief in this sample is multi-generational, with parental higher education attainment being associated with lower odds that respondents viewed religion as important (mother HE: 0.889, p < 0.05; father HE: 0.904, p < 0.05).

A gender effect was observed, indicating that women were more likely to nominate religion as important (gender: 1.188, p < 0.01). Non-marital status was associated with a reduced probability of identification with religious values, with respondents in de facto relationships (living together: 0.756, p < 0.01) or involvement in relationship breakdowns (divorced: 0.867, p < 0.05; separated: 0.793, p < 0.05), having reduced probabilities in comparison with married respondents. Respondents with children were more likely to cite religion as being important to them (children: 1.129, p < 0.01).

Citizenship and economic factors influenced respondent perceptions. Non-migrant status (non-migrant: 0.827, p < 0.01) was associated with a negative effect on respondents’ perceived importance of religion. Economic effects accorded with received evidence on religious participation. For instance, while private sector employment was associated with a reduction in the probability of religion belief compared to public sector participation (private industry: 0.831, p < 0.01), participation in the non-profit sector was associated with a substantially higher likelihood of placing importance on religion (private non-profit: 1.340, p < 0.01). Participation in the non-profit sector is consistent with the importance of helping others as a common theme in many religious traditions, and many scientific studies have found a link between religiosity and helping (Einolf, 2011). Household income level was negatively correlated with the dependent variable, with respondents from low and medium income levels more likely to ascribe importance to religion (low: 1.171, p < 0.01; medium: 1.103, p < 0.1). Again, no effects were present for any of the social class variables.

At the country level, there was a significant and negative effect associated with middle-income countries (middle GDP per capita: 0.612, p < 0.01) and a range of effects across the Inglehart-Welzel category variables compared to the omitted English-Speaking category control group—notably, strong positive effects among respondents from countries in the African-Islamic (15.626, p < 0.01), Latin America (6.920, p < 0.01) and West & South Asia (3.060, p < 0.01) categories.

The influence of higher education on values: evidence from sub-samples

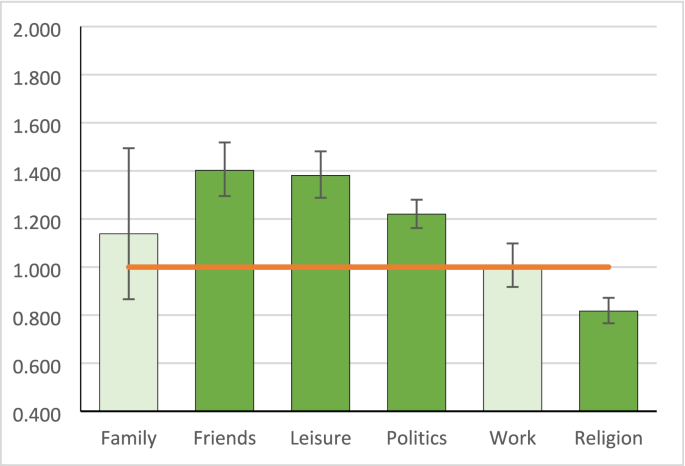

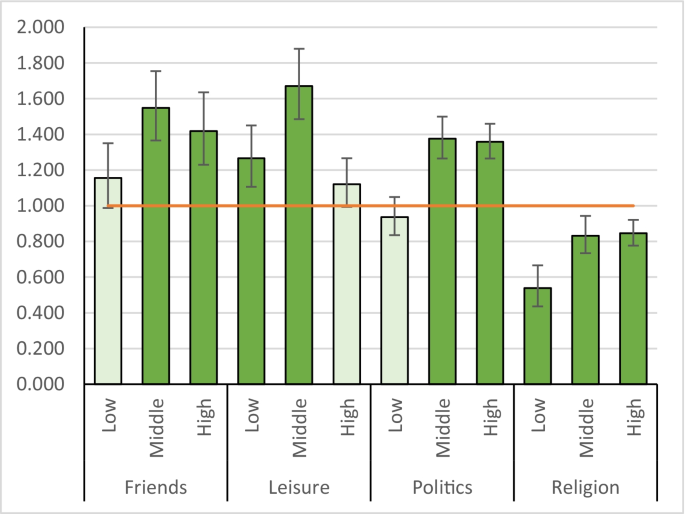

The analysis of the main sample indicated that higher education attainment affected respondents’ views on the importance of certain values. This is summarised in Fig. 1 below, which graphs the odds ratios for the higher education variable in each value model in Table 3.

Odds ratio for higher education in each value model, main sample. Estimated odds ratios and the upper and lower limits of the 0.95 confidence interval for the higher education variable in a model of each value. Darker shading indicates that the estimate of the odds ratio is statistically different from 1.000 at the 0.05 level, lighter shading that it is not

Higher education attainment was significant in increasing the odds that respondents viewed friends, leisure, and politics as important, and reducing the odds of them viewing religion as important, while being statistically insignificant in relation to family and work.

As noted in the discussion above, given the near universal importance attached to family in response data in the main sample, the insignificant impact of higher education attainment was not unexpected. That attitudes to work did not differ in a statistically significant way in this model is also perhaps not entirely unexpected considering over 91% of both higher education graduates (91.2%) and non-graduates (91.8%) nominated it as being important.

Moving to the four values for which a statistically significant effect was observed, it is tempting to view this as evidence for the secularising influence of higher education, with a reduction in the importance attached to religion, coupled with a tendency to view friends, leisure and politics as being important.

These effects were also tested in sub-samples by gender, generation and country grouping.

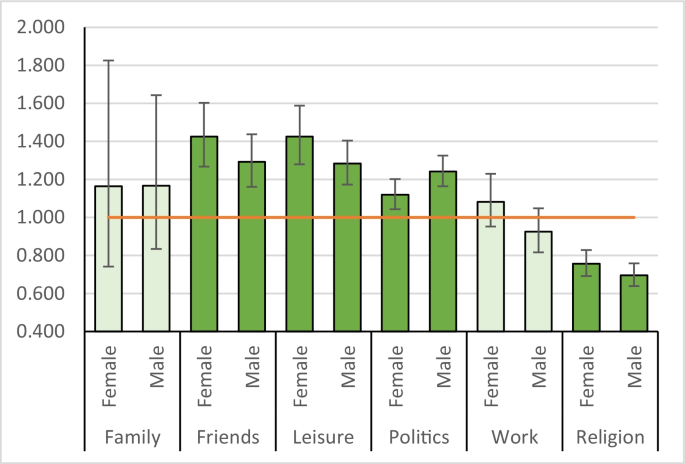

Gender

Splitting the main sample into gender sub-samples allowed us to examine the influence of higher education attainment by gender. The odds ratios for the higher education variable in the gender sub-sample models are represented in Fig. 2 below.

Odds ratio for higher education in each value model, gender sub-samples. Estimated odds ratios and the upper and lower limits of the 0.95 confidence interval for the higher education variable in a model of each value, estimated using the gender sub-samples. Darker shading indicates that the estimate of the odds ratio is statistically different from 1.000 at the 0.05 level, lighter shading that it is not

Following the findings from the main sample analysis, no statistically significant gender-specific effects were present in relation to the influence of higher education attainment in the family or work value models. The effect of higher education attainment was larger in determining the attitudes of female respondents to friends and leisure than was the case for males, while among male respondents, stronger effects were observed for religion—where a lower odds ratio indicated less likelihood that male respondents would nominate this value as important—and politics.

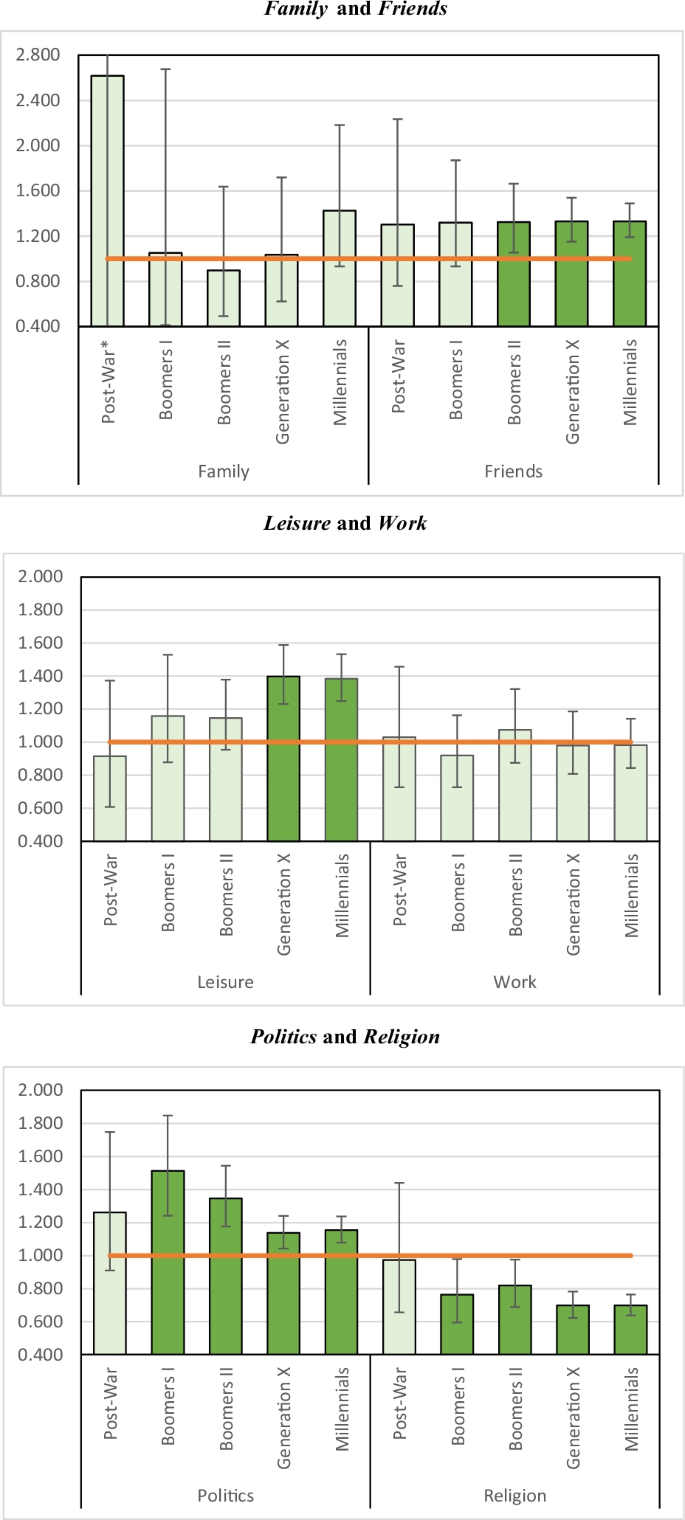

Generation

Turning to the generation sub-samples, again, there was no observed effect for higher education attainment in relation to family or work values, as seen in Fig. 3. The value attached to family appeared to be universal across sub-samples, as indicated in the main sample averages reported in Table 2. By comparison, work was the value that saw the most marked variations in terms of reported importance across generations. The absence of a higher education effect in generation sub-samples indicates that work attitudes reflect broader life-cycle and economic trends affecting entire cohorts, which are independent of higher education attainment.

Odds ratio for higher education in the value models, generation sub-samples. Estimated odds ratios and the upper and lower limits of the 0.95 confidence interval for the higher education variable in a model of each value, estimated using the generation sub-samples. Darker shading indicates that the estimate of the odds ratio is statistically different from 1.000 at the 0.05 level, lighter shading that it is not. * In the family model using the Post-War sub-sample, the upper and lower limits of the 0.95 confidence interval for the higher education variable were 25.043 to 0.274

Overall, there were no observed effects attributable to higher education among the Post-War generation, reflecting a combination of respondents’ shared experience of current life circumstances in post-retirement, the relatively low levels and therefore prominence of higher education attainment for that generation, and the still emerging influence of modernisation and globalisation in terms of value formation for them.

However, higher education attainment was significant in models of the four other values. It was positive and highly significant in explaining the probability of respondents attaching increased importance to friends and leisure. While these effects were comparable between the genders, they were differentiated across generations, with older generations exhibiting no significant effects. In relation to friends, sub-samples of respondents from the three younger generations—Boomers II, Generation X and Millennials—indicated that higher education graduates were around 33% more likely than non-graduates to nominate friends as important.

For leisure, a more pronounced effect was associated with higher education attainment in younger cohorts, with Generation X and Millennial graduates almost 40% more likely than non-graduates to nominate this value as important.

The overall sample means reported in Table 2 show a rising proportion of all respondents valuing politics as important in a comparison of generations, compared to a decline in the valuing of religion. From this, it appears that the level of engagement with politics, if not political institutions, is widespread in the younger generations, whereas declines in the reporting of religion as a value are increasingly concentrated among higher education graduates in generations where attainment is higher. This was borne out by re-estimation of the politics and religion value models using the generation sub-samples.

The results for politics were intuitive given the notion of cultural convergence between graduates and non-graduates over time. Again, there was an observed positive influence of higher education attainment on the odds of respondents in the main sample nominating politics as important, with no observed gender effects. However, there were pronounced effects present across the generations—from Boomers I to Millennials—but with the influence of higher education attainment waning. For instance, graduates in the Boomers I cohort were 50% more likely than non-graduates to place importance on politics, with this likelihood declining markedly across younger cohorts, reaching around 14% for Generation X graduates, with a marginal increase in effect for Millennials (15.5%, from: higher education: 1.155, p < 0.01). This suggests a convergence between graduates and non-graduates on their views of the importance of politics.

The study confirmed the negative association between higher education attainment and religion observed in previous studies. The analysis using the generation sub-samples provided some evidence for an ongoing divergence between graduates and non-graduates in their views on the importance of religion—with Boomers I graduates 76% (higher education: 0.763, p < 0.01) as likely as non-graduates to nominate religion as important. By comparison, graduates among Millennials were less than 70% as likely as non-graduates in their cohort to do so. In effect, not only as the general importance of religion declined across the generations, but the divergence between graduates and non-graduates has also widened, although there is evidence that this has stabilised among younger generations (higher education odds ratios—Generation X: 0.698, p < 0.01; Millennials: 0.699, p < 0.01).

Country grouping

To check the extent to which observed effects occurred across countries, an examination of country grouping sub-samples was undertaken, the first for a division of countries by GDP per capita (low, middle and high) groupings and the second by the stylised Inglehart-Welzel categories listed in Table 1.

The analysis by GDP per capita groups confirmed that higher education was largely insignificant in explaining respondent’s perceived importance of the family and work values—with only one significant and seemingly anomalous result in estimation across 11 sub-samples in each case. Modelling of the four values with consistent effects attributable to higher education attainment—friends, leisure, politics and religion—resulted in broadly consistent findings across sub-samples (see Fig. 4). Of interest though was the seeming convergence between graduates and non-graduates’ valuation of religion as national income rises, perhaps attributable in part to both the decrease in religiosity with income (Inglehart and Baker, 2000) and also the tendency for higher education participation to increase with national income (Marginson, 2016; OECD, 2021).

Odds ratio for higher education in four value models, GDP per capita sub-samples. Estimated odds ratios and the upper and lower limits of the 0.95 confidence interval for the higher education variable across four values, estimated using the per capita GDP sub-samples. Darker shading indicates that the estimate of the odds ratio is statistically different from 1.000 at the 0.05 level, lighter shading that it is not

There were some notable insignificant effects, with no statistically significant difference between graduates and non-graduates in the low GDP per capita sub-sample on the importance placed on friends and politics, and in the high GDP per capita sub-sample, on leisure, suggesting that observable differences between graduates and non-graduates in the former tend to emerge as societies become richer, but dissipate in the latter. The response summary data in Table 2 indicates that leisure is a “normal” good or value at the national level, with an increasing percentage of respondents nominating it as important as GDP per capita increases—74.9% of respondents in low GDP per capita countries compared to 90.2% of respondents in high GDP per capita countries.

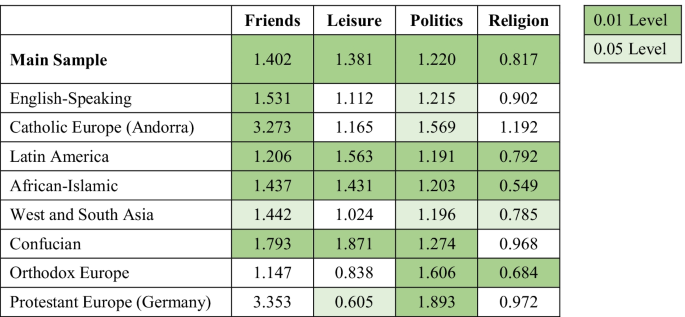

Estimation using the Inglehart-Welzel category sub-samples was also undertaken. This confirmed the finding from the main sample that higher education variable was largely insignificant in the family and work value models. In relation to the other four values, as per Fig. 5, the sub-sample analysis showed a consistent, if somewhat dispersed, higher education effect across the Inglehart-Welzel categories. This was most notable in politics, where there was a statistically significant positive effect attributable to higher education in all sub-samples. Generally, the sub-samples confirm trends seen overall, with higher education attainment driving an increase in the reported valuation of friends, leisure and politics, at the expense of religion.

Odds ratio for higher education in four value models, by Inglehart-Welzel category, sub-samples. Estimated odds ratios for the higher education variable across four values, estimated using the Inglehart-Welzel category sub-samples. Darker shading indicates that the estimate of the odds ratio is statistically different from 1.000 at the 0.01 level; lighter shading, at the 0.05 level; and no shading, that the estimate is not statistically different from 1.000 at the 0.05 level

Conclusion

Widening higher education participation and attainment, leading to the emergence of HPS in middle- and high-income countries, has been a feature of modern economic development. It is a global phenomenon that is considered to exert influence on country-specific values beyond the influence of other factors, such as rising income levels and the emergence of global mass media.

In paper, we have examined the extent to which higher education attainment affects the importance people place on the six core values from the WVS. Attainment was not significant in explaining respondent views in relation to family, a value with near universal acceptance of being important, or work, another value with majority acceptance. The centrality of these values to respondent’s self-perceptions was uniform across gender and generation sub-samples, as well as cross-country sub-samples. However, statistically significant effects were present elsewhere, as higher education attainment increased the propensity of respondents to nominate friends, leisure and politics as important and lowered it in relation to religion.

The inclusion of a broad sample, one crossing gender, generations—and respondents’ position in the life-cycle—country income and cultural disposition indicated that this measured effect of higher education attainment was relatively consistent across values. This raises questions around the extent to which secularisation is an important facet of higher education’s influence on values, with graduates de-emphasising it in favour of relationships, leisure activities and political interests.

A question around convergence in values also emerges, whereby as higher education attainment has expanded—both across generations and the country income spectrum—the uniqueness of higher education graduates’ lived experiences is diminished relative to that of the general population. Evidence from the sub-samples organised by generation and country grouping provided some interesting questions for future research. In the generation sub-samples, where there was increasing levels of higher education attainment and greater exposure to modernist/globalist forces, among younger cohorts, there was evidence that differences between graduates and non-graduates have in fact widened in recent generations. For instance, the value graduates place on leisure and religion appears to diverge from that of non-graduates in Generation X and Millennials, with graduates having a higher odds of valuing leisure and lower odds of valuing religion than non-graduates, compared to the effects observed in earlier generations (that is, the odds ratios are diverging from 1.000 across generations in each instance).

In contrast, the analysis of the GDP per capita sub-samples indicated a convergence in responses for friends, leisure and religion across the country income spectrum, with the estimated odds ratio on the higher education variable converging on 1.000 in a comparison of results across the three groups (low to high). However, there was also evidence of a divergence between graduates and non-graduates on the importance attached to politics in this comparison.

Given the gradient in higher education participation and attainment in regard to generation and country income, it appears that a “scale effect” may apply to the influence of higher education on respondent opinions on the six values, with graduates seeing benefits in terms of the increased levels of leisure and friendships, a decreased connection to religion, but an increased importance attached to political issues and engagement, with the latter emerging as the key point of differentiation between graduates and non-graduates. However, this effect seems more pronounced across generations than across country income levels. This idea is worth investigating, accompanied by an extension of this analysis to other collected variables in the WVS, including respondents’ views on social questions and general views around political, economic and social organisation.

More generally, the examination of higher education’s impact on values needs to address the extent to which the era of HPS in higher education both addresses and reinforces social disadvantage and stratification.

References

Atherton, G., Dumangane, C., & Whitty, G. (2016). Charting equity in higher education: Drawing the global access map. Pearson.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Boero, G., Nathwani, T., Naylor, R. and Smith, J. (2021). Graduate earnings premia in the UK: Decline and fall? The Warwick Economics Research Paper Series. No. 1387. Department of Economics, The University of Warwick: Coventry

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human developments: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Brooks, R. (2007). Friends peers and higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(6), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690701609912

Buell, F. (1994). National culture and the new global system. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Burda, M.C., Hamermesh, D.S. Weil, P. (2007). Total work, gender, and social norms. IZA Discussion Paper No. 2705. Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn

Central Intelligence Agency. (2021). The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/

Crivellaro, E. (2016). The college wage premium over time: Trends in Europe in the last 15 years. Inequality: Causes and Consequences (Research in Labor Economics, Vol. 43). Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley. 287–328.

Einolf, C. J. (2011). The link between religion and helping others: The role of values, ideas, and language. Sociology of Religion, 72(4), 435–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/srr017

Elias, P., & Purcell, K. (2004). Is mass higher education working? Evidence from the labour market experiences of recent graduates. National Institute Economic Review, 190, 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/002795010419000107

Feldmann, H. (2020). Who favors education? Insights from the World Values Survey. Comparative Sociology, 19(4–5), 509–541. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-BJA10018

Gifford, R., & Nilsson, A. (2014). Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour A review. International Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12034

Glaeser, E. L., & Sacerdote, B. I. (2008). Education and religion. Journal of Human Capital, 2(2), 188–215. https://doi.org/10.1086/590413

Gravett, K., & Winstone, N. E. (2020). Making connections: Authenticity and alienation within students’ relationships in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1842335

Hackett, C., McClendon, D., Potančoková, M., & Stonawski, M. (2016). Religion and Education Around the World. Pew Research Center.

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., Puranen, B., et al. (Eds.). (2020). World values survey: Round seven – country-pooled datafile. Madrid: JD Systems Institute. https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.1

Hartog, J., & Oosterbeek, H. (1998). Health, wealth and happiness: Why pursue a higher education? Economics of Education Review, 17(3), 245–256.

Hillygus, D. (2005). The missing link: Exploring the relationship between higher education and political engagement. Political Behavior, 27(1), 25–47.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP16–026. August 2016. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/trump-brexit-and-rise-populism-economic-have-nots-and-cultural-backlash#citation

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51.

Kam, C. D., & Palmer, C. L. (2008). Reconsidering the effects of education on political participation. Journal of Politics., 70(3), 612–631.

Marginson, S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education., 72, 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0016-x

Marginson, S., & van der Wende. M. (2007). Globalisation and higher education. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 8. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/173831738240.

Marginson, S. (2018). High participation systems in higher education. in Cantwell, B., Marginson, S., and Smolentseva, A. (eds.). High participation systems in higher education.

Matei, M.-C., & Abrudan, M.-M. (2018). Are national cultures changing? Evidence from the World Values Survey. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 238, 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2018.04.047

Nie, N. H., Junn, J., & Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and democratic citizenship in America. University of Chicago Press.

OECD. (2009). OECD Social indicators: Society at a Glance. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019). Higher education and the wider social and economic context. In Benchmarking Higher Education System Performance. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/15ff30ce-en

OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en

Perrin, A. J., & Gillis, A. (2019). How college makes citizens: Higher education experiences and political engagement. Socius, 5, 1–16.

Picton, C., Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Hardworking, determined and happy’: First-year students understanding and experience of success. Higher Education Research & Development., 37(6), 1260–1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1478803

Ritzer, G. (1996). The McDonaldization of Society: An investigation into the changing character of contemporary social life. Pine Forge Press.

Rosenbaum, J., & Rosenbaum, J. (2016). Money isn’t everything: Job satisfaction, nonmonetary job rewards, and sub-baccalaureate credentials. Research in Higher Education Journal, 30. https://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/162430.pdf.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics., 87(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882010

Trow, M. (1973). Problems in the transition from elite to mass higher education. Carnegie Commission on Higher Education.

Trow, M. (2007). Reflections on the transition from elite to mass to universal access: Forms and phases of higher education in modern societies since WWII. In J. F. Forrest & P. G. Altbach (Eds.), International Handbook of Higher Education (pp. 243–280). Springer.

Trow, M. (1974). Problems in the transition from elite to mass higher education. in Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (ed.). Policies for Higher Education. OECD: Paris, 1–55.

UNESCO. (2020). Towards universal access to higher education: International trends. UNESCO (International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean). https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/eng/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Towards-Universal-Access-to-HE-Report.pdf

Wilkins, R. (2015), The household, income and labour dynamics in Australia survey: Selected findings from waves 1 to 12, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research: Melbourne, available at: http://melbourneinstitute.com/downloads/hilda/Stat_Report/statreport_2015.pdf

Yeganeh, H. (2017). Cultural modernization and work-related values and attitudes: An application of Inglehart’s theory. International Journal of Development Issues., 16(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDI-10-2016-0058

Yi, F. (2021). The rise and fall of Confucian family values. Institute of Family Studies. Web Blog (30 April 2021). https://ifstudies.org/blog/the-rise-and-fall-of-confucian-family-values

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This paper uses unit record data from the World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017–2020). The authors have no financial or non-financial interests directly or non-directly related to work submitted for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koshy, P., Cabalu, H. & Valencia, V. Higher education and the importance of values: evidence from the World Values Survey. High Educ 85, 1401–1426 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00896-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00896-8