Abstract

Nursing is an old vocation but is relatively new to the academy, with schools of nursing being established in Western universities in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Their establishment was presaged by earlier moves of the preparation of pre-registration nurses from apprenticeships served in hospitals to tertiary education institutions (mainly community colleges and polytechnics) during the last quarter of the twentieth century. Preparation for a life in the professions has been a feature of universities since their inception. Nevertheless, changing a university’s offerings is contested, and new disciplines and the new academics within them often struggle to establish their legitimacy within the academy. This paper challenges contemporary accounts of nursing as a discipline the weak disciplinary boundaries of which undermine its place in the academy and hamper nurse academics’ development of an academic identity. Drawing on data from interviews with nursing academics, the paper discusses the ways in which the participants are, by their own actions, devising, amending and reinforcing the structures, code, rules and conceptual frameworks of the Nursing discipline. It also considers how, as they do so, these academics achieve a level of ontological congruence that is only possible as their internal biography, the nature of their day-to-day work and the expectations of their employer are able to ‘rub along’ together without creating the conditions for (self) destructive resistance or the exercise of coercive institutional power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout, history universities have welcomed new students to study in new programmes that prepare them for a broad and changing range of professions and disciplines. The massification of Western universities evident since the end of World War II has seen an acceleration of this pattern. As new professions turn to universities to educate their members, new academics join the academy and new knowledge is produced. However, claims to academic status for new professions and the disciplines and academics associated with them are often contested. Finding a place in the academy requires new professions to develop a discursive regime of conceptual frameworks and structures within which to nest the rules that will constitute the university discipline and be recognised as such.

Nurse education is a relatively recent addition to university offerings drawing most of its academic staff to schools of nursing from the ranks of practicing nurses. Like any practitioners who make such a transition, nurses face a period of ontological uncertainty as they establish an academic identity adjunct to or replacing a well-established clinical nurse identity (Barrow & Xu, 2021). Some authors have suggested that this ontological uncertainty is exacerbated by the recent move of nurse education to universities and, as a consequence, nursing’s lack of firm epistemological foundations and its weakly defined disciplinary norms (for example, Findlow, 2012). Such claims reinforce a commonly held view that the power relations enabled by well-established disciplinary norms and practices confer status within the university and are also the single greatest influence on academic identity formation (for example, Barnett, 2000; Findlow, 2012). This paper seeks to explore the interlacing relations between the academy, the emergent norms of academic nursing and nursing academics by considering the voices of academics working in nursing schools and the ways in which they are constituted as academic subjects (Foucault, 1988).

The evolution of academic nursing

In most Western jurisdictions, the first degrees for preregistration nurses were offered from the late twentieth century (Andrew et al., 2009, 2014; Duffy, 2013; McNamara, 2010). As in many other countries, New Zealand’s earliest nurses were independent, untrained practitioners. From the 1880s until the 1970s, hospital-based nursing training, founded on Nightingale-inspired models, was in place. In this regime, both nursing practice and education were under direct medical control with new nurses absorbing the skills and culture of nursing during live-in apprenticeships in secondary-care hospitals.

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, as health care and its delivery became increasingly complex, calls grew to move away from an apprenticeship model of nurse preparation. By the end of the 1970s, nursing training in New Zealand had moved into the polytechnic sector, and by the mid-1990s nursing registration was based on baccalaureate degrees. Since 2000, nursing education has been offered in some New Zealand universities. While precise timings may differ, the New Zealand pattern is one similar to that found in many Western countries.

The shift in the location of nursing education is significant in terms of disciplinary formation, of curriculum control and the power relations in play. In hospital settings, medical professionals determined the basis of the nursing curriculum. Hospital-trained nurses acquired medically derived knowledge and applied it under the jurisdiction of their medical masters. In this discursive complex, it was doctors and medicine that were empowered to speak knowledgeably about nurses and nursing. In the initial shift to institutions such as polytechnics (in New Zealand) or community colleges (in the USA), curriculum was developed and controlled by expert nursing practitioners who had made the move to teaching positions. The introduction of nursing programmes to universities (many of these research-intensive universities) has again moved the control of curricula, this time into the hands of research-active academics. The shifting spaces of nursing education—hospital, polytechnic/community college, university—enable new (non-medical) discourses and discursive rules to define nursing and enable new power relations to dominate.

Institutional curricular control is by no means absolute. The discursive landscape in which all disciplines operate, especially those associated with professions, is influenced by a number of players. Professional registration bodies have a significant influence in the curriculum of universities within those programmes that lead to registration within the profession. Where nursing academics are likely to have greater influence, individually and collectively, is in defining and refining the boundaries of the nursing discipline through their research endeavours. In the combination of developing nursing curricula and their research programmes, nursing academics not only embed nursing more firmly within the academy; they also progressively define the boundaries of the discipline and in doing so also strengthen their academic identity.

Academic identity and economic claims on university life

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries saw a surge in scholarly writing about academic identity. The setting off point in some of this literature is a sense of mourning for a lost academia, one replaced by an institution accommodating new types of academics, supporting new and unfamiliar disciplines, struggling with overwork, new employment arrangements and new expectations in terms of teaching, research and service.

This literature often places economic claims on universities at the heart of these changes. These economic claims are manifested in institutions seen to be inflected with new public management ideals and approaches, feeling the effects of the massification of higher education, concerned with producing graduates interested with their own advancement rather than society’s, a preference for applied knowledge development and subject to changing forms of university governance. In this seam of the literature, authors have described and discussed the changing nature of academic labour and the socialisation of academics. They have explored the implications of these changes on the development of an authentic academic identity and on the extent to which academics are able to reach a state of ontological security through their work (see for example, Gill, 2009; Canizzo, 2018; Osbaldiston et al., 2016). This literature often explores the effects changing governance structures and work processes on academics. It also frequently addresses the effect of university structures on groups of individuals, for example, Archer (2008) explores the gendered and classed ways in which these structures act.

Academic identity and ontological security

Zygmunt Bauman (1996) posits that identity has the ontological status of a project and a postulate. At its core, one’s identity is a work that is never completed (a project), and at any point there exists a self that can only be assumed to be true (a postulate) (Barrow et al., 2022). As Bauman further notes the ‘problem of identity’ differs in modern and postmodern times. In the former the problem was constructing and maintaining an identity; in the latter it is ‘how to avoid fixation and keep the options open’ (p. 18).

Keeping options open means on one hand ongoing uncertainty and on the other a constant quest to escape that uncertainty. Such a quest has an ontological inflection concerned as it is with our human being, being in the world and our everydayness. We must, Bauman says, determine ‘how to go on in each other’s presence’ (p. 19), a determination that all academics must address within their working lives. Canizzo (2018) argues ‘that universities harbour cultures that encourage the search for experiences of authenticity between one’s self and labour …’ (p.92). It seems likely that such authenticity can be achieved if there is some level of coherence amongst one’s internal biography (one’s self), the nature of one’s work, what your employer asks you to do, the attitudes of close colleagues and the policy settings that affect your day-to-day activities. These institutional practices act as modes of objectification, transforming the person into a subject (Foucault, 1982). If an academic is able to achieve a level of coherence, ontological congruence may be achieved. That is, a state where the object the institution seeks to create and the subject one seeks to become are able to coexist, reaching a satisfactory level of détente that enables each to ‘rub along’ without inducing (self) destructive resistance or coercive institutional power in order to exert control over a person’s conduct.

Academic identity, disciplines and disciplinary norms

Rose (1999) suggests that with control over conduct is ‘both made possible and constrained by what can be thought and what cannot be thought at any particular moment in our history’ (p. 8) and so government and thought are inextricably bound.

Within the university, disciplines are manifestations of norms associated with particular ways of organising learning and for the systematic production of new knowledge (Krishnan, 2009) setting the boundaries for what might be thought. In a relatively pragmatic manner, Krishnan says that academic disciplines must, to a greater or lesser extent, adhere to six tenets. They should be taught in a university within some sort of recognisable academic unit, have an object of focus for research, accumulate specialist knowledge, rely on theories that organise such knowledge and have specific terminologies and research methods. The operation of these tenets disciplines academics as they take on the rationality of the discipline and its values as their own (Foucault, 1977). Thus, the norms associated with their discipline constrain and enable their academic identity development.

For example, Henkel (2005) points to the influence on biologists of doctoral and postdoctoral study which establish ‘the focus, theoretical base, methodologies and epistemic criteria’ (p. 167) which establish a set of norms that will guide the biologists’ future work, guide their development of coherent research programmes and forge their academic identity.

Like Henkel, McNamara (2010) suggests that a coherent academic identity (and a similar professional one) depends upon there being distinct boundaries between disciplines and fields of practice, respectively. He posits that the development of academic nursing (and therefore nursing academics) is hindered by difficulty in defining and articulating a distinctive knowledge base or knowledge structures normally associated with a discipline. He concludes that academic nursing is in search of the internal coherence needed to be able to develop a distinctive presence within academia.

Both these writers recognise that the foundations of disciplines are subject to conflicting forces that will make academics continually re-evaluate their epistemic identity. In fact, disciplinary norms and those areas that might be accorded the status of a discipline are not set in stone. Their development is constrained by a discursive environment typically established over time and evolving in the interplay of the influences of state authorities, the marketplace and of an academic oligarchy (Clark, 1983). Amongst them, these actors regulate academics’ conduct as they constrain and enable, each to varying extents, what can and cannot be thought about at any moment in history (Rose, 1999). It is their thinking, writing and speaking that set up ‘the discursive rules that produce and define reason’, rules which are ‘linked to the exercise of power’ (Ball, 2013, p. 21).

And while nursing academics in this study and the biologists in Henkel’s will play a role in these processes, they are also subject to a range of power relations played out in university settings and in the case of nursing academics, clinical settings that govern their conduct at collective and individual levels.

The interplay of this group of actors and the balance of their influence varies from discipline to discipline and across time and location. However, much of the literature suggests that economic claims on academic life, represented by the influence of state authorities and the marketplace, have become more prevalent and influential in the period since the end of World War II with a resulting performative turn across many disciplines, and a greater influence from non-academic actors. In The University in Ruins, Readings (1996) discusses the economic claim on university life in relation to the university’s research mission. He suggested that within this domain, thinking is dominated, on one hand, by a ‘traditional’ concern with culture and its development and, on the other, by a ‘contemporary’ concern with the marketplace and with what he calls a techno-bureaucratic notion of excellence. In his thinking about curriculum, Barnett (2000) suggests that pragmatic concerns (many influenced by economic claims) have become increasingly embedded in the structures of disciplines (and universities) influencing the topics, frameworks and concepts that they enfold. He notes that in their role as curriculum developers, academics have to balance the desire to develop a curriculum that is primarily a site of social processes in its own right, against dealing with the way in which the outside world “interpenetrates higher education” curricula (Barnett, 2000 p. 257). Barnett suggests that the academic must situate the curriculum in its wider social context, addressing the interplay between external factors and more ‘academic’ imperatives. Within research and teaching, academics and universities must seek a balance among the domains of being, knowing and acting and therefore an awareness of the extent to which the curriculum, research and the discipline they enact balances projects of ontology (self-identity), epistemology (knowing) and praxis (action) (Barnett, 2000).

These ongoing debates and shifts and their associated discourses challenge strongly held (and ‘traditional’) understandings of the place of universities in society, raise questions about what is worthy of research and teaching in the university and therefore what might be accorded the status of a discipline. These currents intersect at the level of individual academics, affecting the ways in which they consider themselves as academics and the role they might play in society; in other words, they affect their academic identity and their quest for ontological congruence.

Rose (1999) considers works like these on academic identity, the role of the university and so on, a form of quasi-philosophical meditation upon our present, upon the fragmentation of our ethical systems, the dissolution of old certainties, the waning of an epoch of modernity and the hesitant birth of another, whose name is not yet known” (p. 11). Rose suggests that, actually, this is too grandiose a scale of consideration. Instead, he suggests that ‘attention to the humble, the mundane … the small contingent struggles, tensions and negotiations that give rise to something new and unexpected’ (p.11) might be more productive. While holding these considerations in mind, this paper attempts to direct attention to the everyday by giving voice to nursing academics and ‘their identifiable ways of thinking and acting’ (p. 173) as they go about the formation and reformation of their academic and professional lives, turning themselves into academic subjects. In so doing, the paper attempts to consider the ‘social, political, discursive and technological shifts’ (p. 173), which govern the conduct of nursing academics in order to examine the productive effects of various power relations (Foucault, 1983) particularly in relation to their research work might affect the interplay between the development of nursing as a discipline, academic identity development and the power/knowledge hybrid that is called into being by the interactions that play out in this space.

This study

This paper draws on the views of nursing academics who took part in semi-structured interviews about their academic work and their evolving sense of academic identity. The participants were employed in two New Zealand nursing schools. One of the schools is in the University of Auckland, a comprehensive, research-intensive university founded in 1883. The nursing school was established in 2000 and is part of a faculty grouping comprising schools of medicine, medical science, optometry, pharmacy and population health. The school’s preregistration nursing programme is small with the bulk of its students enrolled in graduate and doctoral study. The other school is at Auckland University of Technology, a university that came into being at the start of the twenty-first century through the re-designation of an existing institute of technology (polytechnic) with well-established nursing education programmes. The school is in a health science’s grouping with a number of allied health disciplines including midwifery, podiatry, psychotherapy and oral health. Its nursing school offers a large preregistration programme as well as graduate and doctoral programmes.

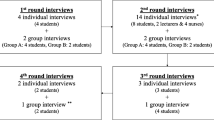

A total of 15 participants were interviewed (10 participants from the University of Auckland and five participants from the Auckland University of Technology). All participants were working in an academic role that required both research and teaching and had at least five years of experience working as a nurse in a clinical setting. Interview participants were asked, prior to the interview, to develop a timeline on which they noted key events on their path to becoming academics. They were also invited to bring to the interview any artefacts that they associated with their transition to academic life. Although an interview schedule had been developed as a guide, it was modified at each interview using the information on the timeline and the artefacts to guide the conversation between the participant and the research assistant who conducted the interviews. The interview consisted of open-ended questions related to participants’ career development, the defining characteristics of their nursing and academic identities and any tensions or difficulties experienced during their identity transition or development. Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed.

The interview data were coded using a coding scheme developed by the author on the basis of the nursing literature. The author and a research assistant independently coded the same subset of transcripts. They then met to compare and agree coding, and to review the codes and definitions in order to remove any ambiguities. The remaining transcripts were coded by the research assistant, using the agreed set of codes. The data were analysed to find the particular ways in which the participants described the modification of their identity as they established themselves as nursing academics and the power relations that were influencing any identity shifts. A total of 15 interview transcripts were made and coded. The study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee.

Results and discussion

In this section of the paper, data are used to consider the extent to which the participants’ developing academic identity is influenced first (and briefly) by their work as teachers. The analysis then turns to a discussion of how, in their work as researchers in particular, the participants are involved in defining the boundaries of nursing as an academic discipline and how this, in turn, relates to identity formation.

Nurse academics, teaching, research and academic identity

In the data generated from the interviews, participants conceptualised their academic life differently depending on whether they were considering their role as a teacher or a researcher (noting that the selection criteria ensured the participants were engaged in both activities). This is significant because the academic literature suggests that it is their conception of academic-as-teacher that stifles the development of an academic identity for nurses who transition to employment in the university (Andrew, 2012).

Like most senior nurses, many participants had spent time before joining the university acting as a preceptor, guiding the development of student nurses in a clinical environment. Thus, the ‘identity leap’ required to move from nurse to academic is not a large one within the teaching domain, at least at the level of delivery of a curriculum. The data (as have other authors) suggest that the teaching endeavour appeals to the humanistic values associated with the nursing profession (Findlow, 2012). When talking about teaching, participants described similar feelings to those that they felt (or feel) in a clinical setting and role.

For example, the positive impact of teaching was described as being similar in terms of rewards to those when they saw the positive impact of their care on patients. UoA6 notes that at the end of her life, she will reflect on ‘the most rewarding career … I’ve made a difference to the health care system, I have made a difference to families and older people, I have made a difference to students, you know, being able to inspire people like these guys’. Similarly, AUT4 states ‘I thought maybe by educating the next generation through them you could have more of an influence [on practice]’. She also saw her teaching as ‘push[ing] the agendas [of improved mental health nursing services] forward … for the benefit of people’. Others saw their nursing selves in their interactions with students in different situations, building relationships, sustaining empathy and creating human interactions such as AUT2 who notes ‘you have got a background in caring and it also impacts on your teaching … because for example you have got a struggling student, a student who is very stressed … and then the nurse comes out of you saying “… you have to consider she is a mother” … you kind of get it if you are a nurse academic’. These data do confirm what other authors have suggested—that for nurse academics teaching provides a level of comfort and familiarity making a shift from nurse to nurse educator relatively straightforward. It seems that there is a level of ‘ontological congruence’ between their clinical and teacher selves. As AUT5 put it, ‘I’ve been there I’ve done that, and I can pass that on’.

The data do, however, contradict the view in the literature that being a ‘teacher’ is in some way a barrier to developing an academic identity. While all the participants valued their roles as teachers their view, commonly expressed, was that while ‘an academic can just do research, … an academic can’t just teach’ (AUT3). Such statements do not suggest that in the transition from nurse to academic, the former nurses’ identity gets ‘stuck’ in a sort of liminal zone between the ward and the lecture hall.

So, while some authors (Andrew, 2012; Smith & Boyd, 2012) contend that new nursing academics are motivated to teach rather than research and that this stalls the development of a coherent or complete academic identity, the data from this study suggest otherwise. All the participants were, without exception, committed to the development of research projects and approaches that they saw as foundational to nursing as a discipline and the development of their own identity as an academic.

Nurse academics as researchers

Findlow (2012) suggests that a further impediment to the development of nurse academic identity arises when subjects privilege the values of nursing over those of academia. He suggests that many nursing academics think academic values are obscure and even spurious. A reading of our data suggests that there may be some truth in this.

Participants in this study characterised their motivation to become nurses in fairly stereotypical ways.

That is why I came into nursing because I wanted to be able to work with [people]and have beneficial outcomes for the people that I work with (AUT4),

So, my role as a clinical nurse is about having a conversation with a patient and their family one on one or small group face to face interactions. Whether you are caring whether you are physically washing someone or talking to them it doesn’t matter. It is about being able to share knowledge and support them and provide them with the care that they need (UoA2).

As Findlow suggests and these participants say, the values and motivation of the nurse are (as expressed here at least) clear and unambiguous. These motivations are clearly reflected in their views of themselves as teachers, mentioned in the previous section.

But statement like these are supplemented with the easy connections that most, if not all, participants drew between their research work and the ‘humanistic, holistic’ (Findlow, 2012, p. 131) values they developed as nurses.

For example, many participants emphasised the importance of their research as a way of continuing to benefit patients—‘I came into nursing because I wanted to be able to … have beneficial outcomes for the people I work with. Those drivers are still there today, but the way I do it has completely changed’ (AUT4). Others pointed out that their research had a role in ‘improving professional practice, improving health care’ (UoA5) and they valued running research programmes that are ‘about relationships and it is about making systems work and improving health care’ (UoA6). One participant wanted her research to support her clinical colleagues by ‘showing what we are doing as nurses is absolutely valuable and incredible, and great and now I just want to add the academics into that and the academic rigour to show that it does’ (UoA6).

In a view expressed by many, UoA7 reported:

I actually think that from a nursing academic point of view you shouldn’t just be judged by your research outputs, you know, maybe you should be judged by how much difference you are making in the system in the real world, and I think that is probably around more the transferability of research. (UoA7)

This a view of knowledge production that takes the judgement of value of research endeavours away from academic peers and firmly places such judgements in the hands of the practice community. It is an attitude that coheres with contemporary concerns about the impact of research, impact normally measured by effects beyond the scholarly community. It is also a view that acknowledges a set of power relations that may differ from the nurse academics’ colleagues in other disciplines where the judgement of academic peers of their scholarly work is paramount.

These latter quotes are examples of an alternative sort of accountability to the general public that participants believe set them apart from other sections of society and from their university colleagues in some other disciplines. UoA3 states ‘So when you are a nurse you are recognised as something other than general population, general public, and part of our code of conduct and competencies is around actually we are held to a different standard and a different level of accountability to the general public because of what we do and who we are’. This participant references the power relations set in motion by her professional code of conduct and she explains that she brings these to her research endeavours and links it to her ‘vocation’ (‘Nursing isn’t just a job it is part of what and who you are that is why it is called a vocation in my view’).

This is in line with the desire (see above) to make system improvements or a positive difference to people’s health. This suggests even within the research domain, which the literature contends is more alien to them, nurse academics find ways to maintain a coherent internal narrative and find ontological congruence between being a nurse and being a researcher. They did not (as Findlow suggests) find the values they developed, as nurses, incompatible with those they might bring to an academic life, certainly not the research aspects of academic life. As UoA7 put it ‘I am still a nurse and that influences how I think about things. It influences what I see as important in making a difference in the health system’. Such data lend support to the contention made here that even within the research domain any gap between a clinical nursing identity and an academic one is not an unbridgeable one.

Nurse academics, research and disciplinary boundaries

The participants in this study hold strongly to the (all but universal) view that their research work should inform processes such as ‘setting up services and policy’ (UoA4). This suggests at least the beginnings of the sort of knowledge base or framework for the systematic production of new knowledge and begins to challenge the contention that there is a lack a basis for their research work.

As arguably the primary sites of knowledge production in Western society, universities have an obligation (and perhaps right) to determine the complex of methods, values and norms which should apply within fields of enquiry or within disciplines is strongly held. Thus, academics expect universities to create the conditions required to release the creativity of individual academics to drive knowledge production. Closely associated with this is a ‘traditional’ understanding of the university’s role is the understanding that the ‘quality’ of the knowledge produced (and perhaps its conformity with the discipline’s norms) should be defined and judged by disciplinary peers, whose knowledge of the epistemological underpinnings of the ‘discipline’ empowers and entitles them to take this role.

The participants in this study are well aware that these power relations are in play and so they acknowledge the importance of the symbols and artefacts commonly associated with such knowledge production systems—the completed doctoral degree, publication in highly-ranked journals and grants from prestigious organisations—and the role these play in the development of both their academic identity and as symbols of the quality of their work and the status of nursing research.

In many cases, the participants relay the tensions around these aspects of knowledge production that mirror those felt by many academics. For example, UoA8 who notes ‘So I now have a PhD, I now have four grants that I’ve been successful in which I didn’t think I would be. So, two years of research that is now funded. I feel like I need to redefine what I’m doing. It is sort of like those things are pushing me to really be clear about what my role is potentially as a clinical academic’. Like others she is aware of the power relations established by the quantification of these research artefacts. ‘So, output generation is very well established in the university as an academic. So, you know, your publications, your successful grants, you know, it is very easy to count. In a clinical environment it is not so easy’.

Similarly, UoA3 notes that ‘I feel like I am pulled in directions that are uncomfortable because of the requirements for promotion and requirements for PBRFFootnote 1 and requirements for drawing in grants and what have you’. At the same time, she notes ‘the sense of competition to draw in external funding and to draw in grants; it feels like there is a competition to do that. When you look at statistics about how many applications are successful out of 500 applications for particular grant you might get 10% as successful. That is an awful lot of time spent generating funding and a massive level of competition’.

Others (UoA1; UoA2; UoA5; UoA7; AUT3) talked about the expectations associated with generating grant income, producing publications, the numbers required along with the technologies surrounding these activities that act to create those expectations such as the hierarchy of prestige associated with getting articles published in more prestigious journals, authorship order and gaining grants from particular funding bodies. The participants contrasted grants from foundations (like the Neurological Foundation) which might cover direct research costs with the more prestigious grants from public funding bodies (such as, in New Zealand, the Health Research Council or Marsden Fund) which also fund the time of the academic overseeing the research project.

Simultaneously, the participants in this study described the generation of research ideas, processes and outcomes being determined much more broadly: by ‘healthcare needs’, by nurses in clinical practice, by patients, etc. rather than being dictated only by other academics through their control of the awarding of grants and acceptance of journal publications. The participants also accept that the quality of the knowledge they produce will be defined by its usefulness, with that utility determined by practitioners whose understanding of practice qualify them for this role. Thus, the nurse academics in this study are willing to accept multiple definitions and arbiters of research quality.

The nurse academics embody this association with nursing practice through their overt and all but universal concern for directing their research in ways likely to support or promote positive practice change, improved patient outcomes, and system improvement. In his considerations of curriculum and its design, Barnett (2000) suggests, an intrinsic part of ‘being an academic’ is balancing the dynamic relationship between social interests and epistemological structures and concerns. He also notes that the boundaries of this relationship change from discipline to discipline. This dynamic might also be applied in the research realm and is manifest in the views of the nursing academics who participated in this study. Through their clearly expressed view that ‘practice’ improvement is the target of their research endeavour, they shift the balance of academic nursing towards the addressing of social concerns rather than epistemological ones.

The participants in this study described a commitment to developing a research programme closely connected to practice.

UoA1 notes that this ‘comes from my underlying philosophy about how we should be doing research these days because I value researching with clinicians, researching with patients and families, not researching on them. So for me this health is so complex, so fast paced that for me I need to be out there doing it out there not sitting at my desk trying to work out something removed from the messy reality of social world’.

‘So that is what my research is about experiences patients have, experiences health professionals have is about chronic conditions and so it is all in that sphere of health care. So, academia is an extension of what I do as a nurse because it is taking my nursing that step further in that direction. I could have chosen to be a nurse practitioner and that would have extended my nursing. I could still be a nurse, but I would be practising at a different level’. (UoA3)

‘We still have to understand what important research we need to do. So, it is not about science and finding about cells and receptors. It is about looking more at social science research, looking at issues to do with patient care, patient outcomes. There is a lot of people who is also looking into that’. (UoA9)

The collaborative nature of the work, including the involvement of patients, practicing nurses and other service providers was seen as adding considerable complexity to the work (AUT1). The complexity was, however, seen as inevitable if one is to develop expertise in areas such as the design of service delivery (UoA2), driving policy change (AUT5) and making ‘a difference in the real world’ (UoA7). Making such a difference was contrasted with ‘writing books and worrying about your CV’ by AUT1. Such statements, echoed by others, draw a link between the perceived (and expressed) pragmatism of nurses and nursing and the research they carry out.

This degree of pragmatism lends some support to the arguments expressed in the literature that nursing is impoverished as an academic discipline because it lacks strong epistemological framing (McNamara, 2010; Smith & Boyd, 2012). McNamara (2010) contends that this lack leads to an ‘theoretical discourse with low levels of abstraction, empirical purchase’ (p. 772), making academic nursing somewhat rudderless when it comes to defining and developing an academic identity. In contrast, most of the study’s participants described well-defined methodological approaches to their research that underpinned the transferability of their findings and outputs (AUT1, UoA4, UoA7) and the enduring and potent nature of the changes they were able to bring about (UoA1). These outcomes would not have been possible in the absence of structured and well-executed projects. Data like these suggest a strong ontological congruence between the participants’ research and their identities as academics (and nurses). They also suggest a strengthening of epistemological framing and increasing evidence of a capacity to drive practice change that some parts of the literature suggest is a prerequisite of the disciplinary moniker.

Conclusions

In general, academics in schools of nursing are recruited from the ranks of clinical nurses. Early twenty-first century literature sets out a range of challenges standing in the way of these academic recruits developing a coherent academic identity and therefore being able to thrive in the academy.

This ‘problem’ of nursing academic identity is frequently defined as arising from the relative ease with which recruits adopt the role of teacher while, at the same time, finding it difficult to adopt the role of researcher. The data gathered in this study do not support this. Rather, the participants were clearly of the view that their research productivity is a prerequisite to earning the ‘academic’ moniker. All of them were concerned to display the behaviours and attributes of the researcher and accumulate the symbols of one. All of them value becoming adept in research processes, engaging in grantsmanship, joining research groups, presenting findings at conferences as well as accumulating grants and publishing their work in peer-reviewed journals and books. The participants (as would be the case with any group of academics) did each of these with varying degrees of success.

This literature also suggests that another fundamental issue for nursing and nurse academic identity is that disciplinary boundaries of nursing are ill-defined. This apparent epistemological impediment is said to arise from the lack of what Ball (2013) describes as ‘a unitary practico-cognitive structure, a regime of truth’ … that is required to provide … ‘the unconscious codes and rules or conceptual frameworks’ (p. 21) needed to establish the set of power relations and discursive rules in which these new academics should operate.

The data in this study, though drawn from a small sample, do suggest that clear boundaries are being drawn around the nursing discipline. The participants in this study see the university (or at least their part of it) and their research work as an integral part of the health system—not standing outside of it. As a result, the participants judge themselves as academics based on the extent and nature of the impact of their research on healthcare settings. Disciplinary unity, as it is conceived by the academics in this study, is achieved when the topics, frameworks and concepts that engage them are informed primarily by the ‘outside world’ (the clinical environment and its needs) rather than by disinterested knowledge production.

To this extent, the participants are describing a discipline influenced by increasing economic claims on universities; of the massification of higher education which has led to an increase in the number and range of disciplines such as nursing being offered in universities; and where the increasing complexity of professional work have created ‘social, political, discursive and technological shifts’ (Rose 1999, p. 173) which have cleared the way for nursing students to study in the university and nursing academics to use the university as a home for nursing research. The participants also describe increasingly embedded power relations that enable nursing to continue its emergence as an academic discipline.

The participants in this study, by their own actions within this discursive field, are devising, amending and reinforcing the practico-cognitive structures, codes and rules, as well as conceptual frameworks (Ball, 2013) that are increasingly setting the boundaries of the nursing discipline and the ways in which they, as academics, draw on the past to inform current and future nursing practice (McNamara, 2010). Simultaneously their actions as researchers are creating the conditions for a level of ontological congruence that is only possible when the objects the university seeks to create and the subject these participants seek to become (that is academic as object and subject respectively) coalesce, strengthening the academic identity of nursing academics.

Notes

Performance-based Research Fund. The name given to New Zealand’s national research assessment exercise.

References

Andrew, N. (2012). Professional identity in nursing: are we there yet? Nurse Education Today, 32(8), 846–849

Andrew, N., Ferguson, D., Wilkie, G., Corcoran, T., & Simpson, L. (2009). Developing professional identity in nursing academics: The role of communities of practice. Nurse Education Today, 29(6), 607–611

Andrew, N., Lopes, A., Pereira, F., & Lima, I. (2014). Building communities in higher education: the case of nursing. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(1), 72–77

Archer, L. (2008). Younger academics’ constructions of “authenticity”, “success” and professional identity. Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 385–403

Ball, S. J. (2013). Foucault, Power, and Education. Routledge

Barnett, R. (2000). Supercomplexity and the curriculum. Studies in Higher Education, 25(3), 255–265.

Barrow, M., Grant, B.M., & Xu, L. (2022) Academic identities research: mapping the field’s theoretical frameworks. Higher Education Research & Development, 41, 2, 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1849036

Barrow, M., & Xu, L. (2021). Making their way as academics: A qualitative study examining how nurse academics understand and (re)construct academic identity. Nurse Education Today, 100, 104820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104820

Bauman, Z. (1996). From pilgrim to tourist: Or a short history of identity. In S. Hall, & P. Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity (pp. 18–36). Sage Publications.

Cannizzo, F. (2018). ‘You’ve got to love what you do’: Academic labour in a culture of authenticity. The Sociological Review, 66(1), 91–106

Clark, B. R. (1983). The Higher Education System: academic organisations in cross-national perspective. University of California Press

Duffy, R. (2013). Nurse to educator? Academic roles and the formation of personal academic identities. Nurse Education Today, 33(6), 620–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.07.020

Findlow, S. (2012). Higher education change and professional-academic identity in newly ‘academic’ disciplines: the case of nurse education. Higher Education, 63(1), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9449-4

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Tr. A. Sheridan. Allen Lane Penguin

Foucault, M. (1982). “The Subject and Power,” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 4, pp 777–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343197

Foucault, M. (1983). The Subject and Power (Afterword). In H. L. Dreyfus & P. Rabinow (Eds.) Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics (2nd ed., pp. 208–26). Chicago University Press

Foucault, M. (1988). The history of sexuality (1st Vintage, & Books ed.). Vintage Books

Gill, R. (2009). Breaking the silence: The hidden injuries of neo-liberal academia. Secrecy and silence in the research process: Feminist reflections, 21, 21

Henkel, M. (2005). Academic identity and autonomy in a changing policy environment. Higher Education, 49(1), 155–176

Krishnan, A. (2009). What are academic disciplines? Some observations on the disciplinarity vs. interdisciplinarity debate. Microsoft Word - NCRM working paper series_front.doc

McNamara, M. S. (2010). Where is nursing in academic nursing? disciplinary discourses, identities and clinical practice: a critical perspective from Ireland. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(5–6), 766–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03079.x

Osbaldiston, N., Cannizzo, F., & Mauri, C. (2016). ‘I love my work but I hate my job’—Early career academic perspective on academic times in Australia (p. 0961463 × 16682516). Time & Society

Readings, B. (1996). The university in ruins. Harvard University Press

Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: reframing political thought. Cambridge University Press

Smith, C., & Boyd, P. (2012). Becoming an academic: the reconstruction of identity by recently appointed lecturers in nursing, midwifery and the allied health professions. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.647784

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was given ethical approval by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (reference number 021701).

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barrow, M. Ontological congruence, discipline and academic identity in university schools of nursing. High Educ 85, 637–650 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00858-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00858-0