Abstract

This paper, while conceptual in nature, is informed by both research and practice. Exploring the “engagement interface” as the site for student engagement (SE), we offer a conceptual contribution in engaging with the Kahu and Nelson (2018) model by bringing in a fuller understanding of SE grounded in the higher education context rather than being uncritically transplanted from a compulsory education context. This involves consideration of the multiple facets of SE as well as the dynamic, shifting and multilocal nature of the construct. The paper then proceeds to enhance the details of the model, grounding them in a finer-grained reading of the literature and relating educational constructs to the model’s proposed “mechanisms” in a conceptually substantiated way. This further extends Kahu and Nelson’s aim of illuminating the “black box” of SE. Our third contribution is to practice by proposing tactics: informed by the literature, we invite practitioners to consider ways in which they can increase the likelihood of facilitating engagement with, and by, students more constructively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The moral panic spawned by Arum and Roksa (2011) and subsequent publications (e.g. Tinto 2019; Armstrong & Hamilton 2013) led to wide-scale concern that students were unengaged, were learning very little during their time in higher education (HE) and were graduating without the skills and aptitudes required by the contemporary workplace. Student engagement (SE) has been mooted (Harper & Quaye, 2009; Markwell, 2007; Salamonson et al., 2009) as a means to increase student “success”, including retention, progression and learning, based on reported correlations between SE and desirable student outcomes.

Our understanding of SE as

…the interaction between the time, effort and other relevant resources invested by both students and their institutions, intended to optimise the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and the performance and reputation of the institution. (Trowler, 2010:3)

recognises reciprocity of student and institutional investment. It also recognises that benefits accrue to both individual students and the HE institution—and beyond: to the local and national context, and the HE system globally.

This paper, while conceptual in nature, is informed by both research and practice. It was largely provoked by a series of papers (Kahu et al., 2019; Kahu & Nelson, 2018; Picton et al., 2018) which unveiled and discussed the “educational interface” as the site for student engagement. This construct found resonance with our own thinking, although absences and silences within that framework prompted us to extend that work to incorporate our own constructs, producing the model we introduce in this paper.

Our intentions in this paper are to refine the Kahu and Nelson (2018) model, based on our own previous work in this arena (Trowler et al., 2019; Trowler et al., 2020), as well as orientate it toward greater application in practice, grounded in our experience as practitioners and informed by relevant work of others. To do this, we will outline where we feel the model could helpfully be augmented, before considering the multifaceted nature of student engagement, how student engagement can shift and change over time and the dynamics of the engagement interface.

We will then go on to consider in more detail the pathways to engagement, and how these might be harnessed through suggested tactics to increase the likelihood of engaging constructively. Throughout this paper, we make use of a theoretical borderlands (Abes, 2009) approach, drawing on appropriate theoretical perspectives to illuminate the matter under discussion in relevant ways.

The Kahu and Nelson model

Our point of departure from the Kahu and Nelson model lies in their understanding of student engagement. They (2018:59) situate engagement within the individual student, as “an individual student’s psychosocial state”, in contrast to our understanding (captured in the definition, above) which situates student engagement as a reciprocal dynamic: engagement of students, and engagement by students. (While Kahu and Nelson recognise that a student’s engagement may be facilitated by the interaction between the institution and the student—as discussed below—they posit that actual engagement itself is located within the individual student, whereas we understand engagement as a process of, and by, students, thus itself occurring at the interface and not within the individual student. In doing so, they adopt a similar position to Bryson and Hardy (2011) who separate the engagement of students from the engagement by students, deeming only the latter to be SE, and thus locating the construct within the individual student.)

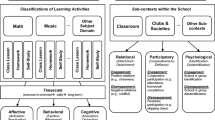

In addition, the Kahu and Nelson model uncritically embraces the Fredricks et al. (2004) depiction of SE as threefold, comprising behavioural, emotional and cognitive dimensions. While we recognise the usefulness of this depiction within the compulsory education context for which it was formulated, we consider that it fails to describe adequately the nature of SE in a HE context. Our own depiction of SE in HE has six facets, as well as congruent and oppositional dimensions, as discussed below.

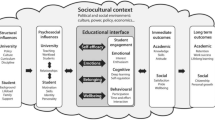

Another point of difference relates to the linearity of the model, which we have illustrated in Fig. 1 (adapted from Kahu & Nelson, 2018). We recognise that SE is not only dynamic, with individual students engaging differently over time, but also that movements can occur in many different directions simultaneously along the different facets, as discussed and illustrated below.

The educational interface, adapted from Kahu and Nelson (2018:64)

The stated motivation for Kahu and Nelson’s paper was to address the lack of a “clear articulat[ion of]… the mechanisms contributing to the individual student’s engagement”. They cited a need to demonstrate how student and institutional factors “interact and impact on the underlying psychosocial mechanisms that influence individual student success” (Kahu & Nelson, 2018:59), which they attempt through identifying four “mechanisms” (or psychosocial constructs).

These four “mechanisms” were reportedly chosen from the literature, based on two criteria: that they correlate strongly with enhanced student outcomes; and that they result from an interaction between aforementioned student and institutional. It is unclear from the paper why only four were chosen, or on what basis these four were deemed the best contenders, or how these four “mechanisms” “trigger” the SE they propose.

In contrast to the four “mechanisms” chosen by Kahu and Nelson (viz. academic self-efficacy, emotions, belonging and well-being), our own engagement with the literature has produced a list of six, three of which (self-efficacy, emotions, belonging) occur on their list, and a further three (motivation, resilience, reflectivity) which do not.

As the literature is constantly evolving, the choice of which “mechanisms” to select represents both a moment in time (when these “mechanisms” are all represented in the literature as strongly (positively) correlated with enhanced student outcomes; another point in time may see other “mechanisms” enjoying greater attention in the literature) and our own subjective interpretation of these “mechanisms” as arising within the “engagement interface” between the student and the HEI, and having some rationally conceivable role in facilitating engagement (Figs. 2 and 3).

Greg’s engagement over time—from Trowler (2017)

Tristan’s engagement over time (from Trowler, 2017)

As evidencing causality (to support claims that these mechanisms result from an interaction between the aforementioned student and institutional factors) would be impossible within the scope of this paper, we have abandoned this requirement and instead posit that the exact origins of these “pathways” are less material than the fostering of conditions which support and enhance these “mechanisms” at the engagement interface.

We mapped our six literature-derived constructs onto the six facets of SE identified in our SE model (discussed below), thus providing a clearer understanding of how such a “mechanism” might operate in facilitating engagement of, and by, students. We have used the term “pathways to engagement” in preference to the alternative “triggers of engagement” used interchangeably in Kahu and Nelson (2018), as this implies that they facilitate rather than actuate engagement.

We have also preferred to use the term “engagement interface” rather than “educational interface”, since we locate engagement at the interface (rather than within the individual student). This also recognises that—while related—education and engagement are not the same thing, and that assuming the locus of one to be the site of the other is potentially problematic.

Student engagement

Student engagement has been described elsewhere as “vague” (Ashwin & McVitty, 2014), or as a “fuzzword” (Vuori, 2014), whose use has involved “chaotic conception” (Trowler, 2015). In contrast to the earlier, more normative and atheoretical literature, more recent work on SE has shifted to a more critical discussion of the construct itself, how it is deployed and what underlies its popularity (see, e.g. Gourlay, 2015; Macfarlane, 2015; Zepke, 2014).

A parallel literature on SE in the compulsory education sector has flourished, largely in isolation from the SE in HE literature, though this has been punctuated by occasional cross-fertilisation. This has led to uncritical importation of ideas from one context to the other, without due consideration being given to implications of the (often stark) differences between school classrooms and HE study contexts. One example of such uncritical import is Zepke’s (2014) annexing of the ideas of McMahon and Portelli (2004, 2012) regarding the “elective affinity” between SE and neoliberalism; another has been the wholesale adoption of the Fredricks et al. (2004) model of the threefold nature of SE, which is discussed further below.

Dimensions of student engagement

As stated above, the Fredricks et al. (2004) model proposed that SE had behavioural, cognitive and emotional components. In addition to these, the Trowler (2010) model, based on a review of the SE literature, proposed an oppositional (formerly “negative”) dimension to describe those activities previously considered outside of the ambit of SE, or even contradictory to SE, which evidenced students engaging with their subject material, courses, institutions or the higher education (HE) system or context more generally but from positions which conflicted with the prevailing interests.

Subsequent empirical research (Trowler, 2015) into SE in HE contexts noted additional facets to the engagement of, and by, students within these HE contexts, in ways that differentiated them from SE in a compulsory education context (illustrated in Table 1). These were identified as critical, political and socio-cultural, and are understood as follows:

-

Critical—how the student relates to the authority (of knowledge; of structures, systems and processes; of identity) and the extent to which this is accepted at face value, interrogated or rejected. This relates to the student’s orientation to authority.

-

Political (in the sense of power rather than ideology)—the extent to which the student assumes agency or consumes passively (relating to production/consumption of knowledge; participating in, challenging, or receiving structures, systems and processes; adapting identity, adopting identity or reshaping identity). This relates to the student’s agency.

-

Socio-cultural—the student’s relationship to the networks of practices embodied in academia, and their own academic context (in the domain of knowledge; relating to structures, systems and processes; concerning identity). This relates to the student’s values.

While the three facets identified by Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris (affective, behavioural and cognitive) continue to matter at HE level, they fail to capture important ways in which “being a student” in a HE context differs from being a student at school or Further Education (FE) college. An obvious difference is criticality, which provides the “higher” in HE, as noted by Danvers (2016), and which is seen as indexical of the success of HE (Barnett, 1997), which is not foregrounded (and may be unwelcome) in compulsory education (CE) and FE contexts. Similarly, political engagement (in the sense of the student’s agency) is viewed as central in HE, with the expectation that students become self-directed learners, in contrast with CE and FE contexts. Ashwin (2019) argues that the goal of HE is to be transformative. We have argued elsewhere (Trowler et al., 2020) that this accords with what Stenhouse (1975) identifies as induction, that is, the suffusion of the culture and thought system, rather than merely becoming familiar with social values and norms (initiation). This is the focus of socio-cultural engagement.

These facets highlight difficulties often faced by students who may be considered “non-traditional” for various reasonsFootnote 1: students who are first-in-family to participate in HE, who hail from low-participation neighbourhoods, who come from lower socio-economic status or financially precarious backgrounds, who are categorised as belonging to a minoritised ethnicity, who have caring responsibilities, who live with their families, who commute rather than living in student accommodation, who have disabilities, etc. These students have often attended schools where reproduction (or “regurgitation”) of knowledge was encouraged as a mechanism to achieve qualifications which are the currency for progress, and thus struggle with engaging critically. Their sense of agency may also have been constrained by their life circumstances, leading to their adopting a passive approach including with their learning. They are also more likely than middle-class students to find the values embodied in HE “foreign” because of habitus mismatch (see Reay et al., 2009).

While HE research has typically focused on the behavioural (see Zepke, 2015), cognitive (Ashwin et al., 2014) or affective (Kahu, 2013) facets, it has seldom considered the intersections of these even within the limits of the Fredricks et al. (2004) mode. In particular, research has been silent on where students engage congruently along one or more of these facets and oppositionally, or not at all, along others, with the limited exception of Payne (2019). The deployment of the construct typically positions SE as a binary (engaged vs unengaged) in the contexts and to the ends authors, policy makers or practitioners deem valid, rather than representing the nuances of how—and to what extent—students are engaging variously with different objects and along the different facets, within a particular context. This leads to a static, linear conception of SE.

In contrast, it is important to note that engagement is not only fluid and changing over time, but also complex and nuanced even at a particular time, with engagement along any of these facets involving multiple simultaneous (even contradictory) positions for different (aspects of) objects of engagement. For example, a student could be bored by Romantic Poetry but engaged by his/her tutor’s teaching of a particular Romantic poem, even while rejecting the construction of the curriculum that includes Romantic Poetry.

Dynamics of student engagement

Kahu and Nelson consider, and reject, the possibility of student transition “theory” being of use to the SE construct, since transition—as they portray it—focuses only on the student’s entry to HE, and thus considers only a single shift of state (from “not-student” to “student”), which neglects for example the reality that student attrition continues in second and subsequent years of study, albeit on a more limited scale. This depiction of student transition ignores the rich literature (see Guyotte et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2014; Semetsky, 2006; Taylor & Harris-Evans, 2018; Trowler et al., 2019) which considers transition not as a “one-off”, but as a continual process of “becoming”, lasting throughout and beyond studenthood, involving agency and negotiation, within the constraints and affordances of context. Instead of this limited depiction of transition, Kahu and Nelson propose deploying Nakata’s (2007) construct of a cultural interface, as an educational interface: “the place where students live and learn in higher education”, specifically “a psychosocial space within which the individual student experiences their education” (Kahu & Nelson, 2018:63).

Within this educational interface, they propose (Kahu & Nelson, 2018: 63-4), “when institutional and student factors align, …individual student engagement occurs” and learning can take place. Thus, they argue, if the curriculum is linked to their interests, experience and “future selves”, students will engage emotionally; likewise, if their skill sets “align with the task at hand”, they will engage cognitively. Aside from assuming that all engagement is necessarily congruent, or that only congruent engagement leads to learning, this proposal depicts students as lacking imagination or agency: that a student’s interest cannot be piqued by a curriculum which introduces material foreign to their (current) interest, experience or (imagined) “future selves”; or that a student cannot rise to the challenge of mastering new skills to tackle an academic task. This raises the question of how then learning does indeed take place.

However, the central concern here relates to the linearity of the model. As proposed, students arrive with their structural and psychosocial influences, and encounter institutions (with their own structural and psychosocial influences) in this educational interface, where if all the factors so align, engagement (and thus learning) can take place, leading to immediate outcomes (of an academic and social nature), which in turn lead to longer term outcomes (of an academic and social nature). In our view, the situation is rather more complex. Students indeed carry with them influences from macro, meso and micro levels, which manifest in their subjectivities and orientations as they interact with the HE institution (itself comprising influences from macro, meso and micro levels, which manifest in its practices). However, students not only move in and out of this “educational interface”, living their outside lives and performing their non-student subjectivities; they also continue to inhabit these “other lives” while simultaneously inhabiting this “educational interface”, which we have thus deemed more accurately to be an “engagement interface”. The backstories that both students and HEIs bring with them, and the outcomes arising from the interaction, are present (at least in germ) in the interactions, creating a dynamic system not easily captured by a linear model (see Fig. 4)

Depicting student engagement over time presents challenges, as Trowler (2015) showed: at any point, students may be engaged congruently, oppositionally or not at all, along each of the six facets, and even within these, across different contexts. Figure 2 (from Trowler, 2017) shows an attempt to map the engagement of a single student over time. In this example, engagement was present in some forms, along some facets, in some contexts, while absent in others, and present in other forms and contexts. Engagement changed and shifted with time—as evidenced by growing level of engagement (congruent or oppositional) along some facets and waning engagement along others—and with context: “Greg” engaged congruently in his affective identification with the professional codes of behaviour of computer games designers, but oppositionally with some of the demands of the socio-cultural positioning of students.

The “tube map” format allows for greater complexity, including multiple points of departure and arrival, many vehicles travelling along the same route, or its variations, simultaneously, in the same or reverse direction. Figure 3 (from Trowler, 2017) uses this format to represent the engagement experiences of a different student—“Tristan”—mapped out in this way, with the green line representing his route, the blue line his depiction of the route of his school contemporaries and the magenta line providing analytical comment. Red lines mark interviews, while multiple branches represent simultaneous “travel” along different routes, of different aspects of engagement. For example, Tristan’s studies represent one engagement route, while his music represents another. Later, his studies again represent one route and his extramural interests (new girlfriend, part-time modelling, working as a film extra) represent other engagement routes.

At a systems level, capturing the engagement of students with the university presents similar challenges. Our attempt is presented in Figure 4.

The engagement interface

As explained above, we have chosen to refer to our model as the engagement interface, rather than the educational interface. In part, this is because we recognise that while engagement and learning are linked, they are not the same thing. Also, we recognise that learning happens in many contexts, not only those ordained as formal education spaces, and that within formal education spaces, engagement and learning may not happen, or may not happen in recognised or approved ways. Since our focus in this paper is on engagement rather than learning per se, this is the focus of our model.

At the interface between the university and the student, depicted in the finger-like projections into each space, we have placed the six facets of engagement (listed in Table 1) together with six factors we have identified from the literature as pertinent to these facets of engagement. These are discussed more fully below.

Pathways to engagement

We have illustrated the “pathways to engagement” together with the facets of SE and examples of tactics to engender engagement inspired by the literature, in Table 2. The discussion below considers these in more detail.

While these strategies in many cases appear to focus on changes within individual students rather than at the institutional level, the intention here is that consideration be given to the curricular and pedagogical space in order to address constraints within these that might hamper some students’ facility to engage fully.

This is particularly important for those students for whom university may be experienced as a hostile environment: our intent here is not to shift the responsibility on to the marginalised student to, for example, develop a more positive emotional response, but rather for the institution to create an environment which itself fosters a more positive emotional ambience for these (and other) students, and which supports the student in strengthening their reappraisal skills to achieve their potential. These processes require time, effort and other resources from both the institution and the individual student, and will—if successful—produce change in both.

Emotions

Emotions may provide a pathway to affective engagement. Emotions are evoked within a situation and are fluid and volatile, arising from an individual’s subjective response to the situation (Fredrickson & Cohn, 2008). MacCann et al. (2011) found emotion management to be positively correlated with academic achievement, while Sirois and Pychyl (2013) found it to be negatively correlated with procrastination. Emotions were identified by Kahu and Nelson (2018) as one of their four “mediating mechanisms”, while Kahu et al. (2015) found that “life-integrated learning” (which they define as material which intersects with students’ interests/experiences) provoked positive emotions related to those topics.

Tactics:

Arising from this, the following tactics may enhance affective engagement:

-

Fostering positive emotions in students (through curriculum, pedagogy, rapport, pastoral input, fostering well-being, etc.)

-

Helping students regulate negative emotions through fostering reappraisal skills (see Gross, 2002) to short-circuit negative associations taking hold

Motivation

Motivation may provide a pathway to behavioural engagement. Schunk et al. (2008) define motivation as “students’ desire and willingness to deploy effort toward, and to persist in, a learning task”. According to Wigfield and Eccles (2000), motivation arises from students perceiving that completing the task will bring (sufficient) benefits, and judging that they have (or can master) the ability to complete the task successfully, while Belland et al. (2013) further link interest and a sense of belonging to motivation.

Tactics:

Arising from this, the following tactics may enhance behavioural engagement:

-

Establishing task value (and ensuring that tasks have value and provide authentic learning experiences (McCune, 2009)), so that students recognise the benefits that completing the task will bring

-

Promoting mastery goals (rather than task goals, or task avoidance) so that students recognise that completing the task will allow them to gain the skills to master other similar/related tasks in future

Resilience

Resilience may provide a pathway to cognitive engagement. Described as “academic buoyancy” by Martin and Marsh (2009), resilience results in constructive reengagement after setbacks and challenges, which is key for progressive development. Resilience, they argue, (Martin & Marsh, 2009) is fostered through interpersonal resources such as good rapport and peer engagement, as well as intrapersonal resources such as self-efficacy and autonomy. “Families of coping”, according to Skinner and Pitzer (2012), such as problem solving, support seeking or escape, can help or hinder the building of resilience.

Tactics:

Arising from this, the following tactics may enhance behavioural engagement:

-

Promoting a student’s awareness of their individual coping strategies (problem solving/support seeking/escape)

-

Fostering a healthy balance, and appropriateness to context, of students’ coping strategies

Reflectivity

Reflectivity may provide a pathway to critical engagement. Reflection provides a bridge between experience and learning (Griggs et al., 2018), and is necessary for self-regulation and metacognition (Mirriahi et al., 2018) and also for transformational learning (Carrington & Selva, 2010). Grant et al. (2002) differentiate between constructive self-reflection and rumination, which they consider a dysfunctional state of self-absorption. Constructive self-reflection, they argue (Grant et al., 2002), leads to insight, which allows one to monitor and improve their performance.

Tactics:

Arising from this, the following tactics may enhance critical engagement:

-

Identifying students’ reflection strategies (depth of reflection, as well as focus of reflection: constructive reflection vs rumination)

-

Providing scaffolding to allow students to adopt more constructive reflection practices and a greater depth of reflection

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy may provide a pathway to political engagement. Bandura (1986:391) defines self-efficacy as “people’s judgements of their capabilities to organise and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances”, and regards it as critical to agency (Bandura, 1997). Enhancing students’ academic self-efficacy increases SE (Chang & Chien, 2015; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2003) and impacts on persistence, goal setting and self-regulation, which in turn increases motivation and learning (van Dinther et al., 2011). Schunk and Mullen (2012) point to a reciprocal relationship between self-efficacy and SE and success. Self-efficacy was also identified by Kahu and Nelson as one of their “mediating mechanisms”.

Tactics:

Arising from this, the following tactics may enhance political engagement:

-

Building students’ awareness of their internal and external resources

-

Fostering reappraisal, to engender positive emotions

-

Encouraging autonomy

Belonging

Belonging may provide a pathway to socio-cultural engagement. Belonging has been linked to engagement, persistence and success (Kuh et al., 2008; Masika & Jones, 2016; Thomas, 2012) and implicated in models of transition (Tinto, 1993; Wayne et al., 2016). Yuval-Davis (2006) distinguishes between belonging and the politics of belonging, noting that these are dynamic and situational, while Trowler (2019) conceptualises belonging as identification with, or aspiring to membership of, “imagined communities”. Belonging was also identified by Kahu and Nelson as one of their “mediating mechanisms”.

Tactics:

Arising from this, the following tactics may enhance socio-cultural engagement:

-

Fostering peer relationships (through orientation activities, pedagogy, etc.)

-

Building staff-student rapport (through pastoral input, personal tutors, etc.)

-

Nurturing congruent values

Kahu and Nelson (2018) list “well-being” as their fourth “mediating mechanism”, as well as listing it as an “immediate outcome” of engagement (see Fig. 1). We have not included this as a mechanism, as we regard it as a meta-construct implicated in, and arising from, the interplay of the aforementioned “pathways”, together with environmental factors.

Limitations and recommendations for further study

This paper is conceptual, albeit informed by research (including our own previous work in this area) and by practice. The arguments presented here could benefit from further work (both conceptual and empirical), unpacking the complexity identified in the model in ways which engage with the realities of diverse student populations and institutional contexts beyond the “bare bones” we have outlined here. In the same way that the Kahu and Nelson papers provoked us to bring our previous work and thinking into dialogue, we hope that our contribution will in turn provoke others to engage to advice the model further.

Conclusion

Engagement of, and by, students is widely regarded as critical to student success. However, understandings of what the construct means are widely contested, and a neglect of the importance of context has given rise to the uncritical importing of models from contexts outside of HE, notably the compulsory education (K-12) sector.

This paper has sought to contribute to conceptual understandings of the SE construct, as well as increasing its applicability for practitioners by offering possible approaches for practice. Firstly, it has offered an important conceptual contribution in engaging with the Kahu and Nelson (2018) model by bringing in a broader, more contextual understanding of SE, grounded in the HE context rather than being transplanted from a compulsory education context. This has involved consideration of further dimension of SE (oppositional as well as congruent; with additional facets—critical, political and socio-cultural—alongside the school-based behavioural, cognitive and emotional) as well as the dynamic, shifting and multilocal nature of the construct.

Our second contribution has been to enhance the details of the model, grounding them in a finer-grained reading of the literature and relating educational constructs to the model’s proposed “mechanisms” in a conceptually substantiated way. This further extends Kahu and Nelson’s aim of illuminating the “black box” of SE. Our third contribution is to practice by proposing tactics: informed by the literature, we have invited practitioners to consider ways in which they can increase the likelihood of facilitating engagement with, and by, students more constructively.

Notes

Students seldom present with only a single one of these factors. It is important to take an intersectional approach when considering the experiences of these students.

References

Abes, E. S. (2009). Theoretical borderlands: Using multiple theoretical perspectives to challenge inequitable power structures in student development theory. Journal of College Student Development, 50(2), 141–156.

Armstrong, E. A., & Hamilton, L. T. (2013). Paying for the Party. Harvard University Press.

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. University of Chicago Press.

Ashwin, P. (2019) Higher education is about transformation, World University News, 13 April 2019.

Ashwin, P. & McVitty, D. (2014) The meanings of student engagement: Implications for policies and practices", Bologna Process Researchers Conference: The Future of Higher EducationBucharest, 24-26 November 2014.

Ashwin, P., Abbas, A., & McLean, M. (2014). How do undergraduate students' accounts of sociology change over the course of their undergraduate degrees? Higher Education, 67, 219–234.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Barnett, R. (1997). Higher education: A critical business. SRHE and Open University Press.

Belland, B. R., Kim, C., & Hannafin, M. J. (2013). A Framework for designing scaffolds that improve motivation and cognition. Educational Psychologist, 48(4), 243–270.

Bryson, C. & Hardy, C. (2011) Clarifying the concept of student engagement: A fruitful approach to underpin policy and practice, HEA Conference 2011Higher Education Academy, York, 5-6 July 2011.

Carrington, S., & Selva, G. (2010). Critical social theory and transformative learning: Evidence in pre-service teachers' service-learning reflection logs. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(1), 45–57.

Chang, D. & Chien, W. (2015) Determining the Relationship between academic self-efficacy and student engagement by meta-analysis, 2nd International Conference on Education Reform and Modern Management (ERMM 2015)Atlantis Press, Paris, pp. 142.

Danvers, E. C. (2016). Criticality's affective entanglements: Rethinking emotion and critical thinking in higher education. Gender and Education, 28(2), 282–297.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Cohn, M. A. (2008). Positive emotions. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions (pp. 777–796). The Guilford Press, New.

Gourlay, L. (2015). "Student engagement" and the tyranny of participation. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(4), 402–411.

Grant, A. M., Franklin, J., & Langford, P. (2002). The self-reflection and insight scale: A new measure of private self-consciousness. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 30(8), 821–835.

Griggs, V., Holden, R., Lawless, A., & Rae, J. (2018). From reflective learning to reflective practice: Assessing transfer. Studies in Higher Education, 43(7), 1172–1183.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291.

Guyotte, K. W., Flint, M., & Latopolski, K. S. (2019). Cartographies of belonging: Mapping nomadic narratives of first-year students. Critical Studies in Education.

Harper, S. R., & Quaye, S. J. (Eds.). (2009). Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations. Routledge.

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773.

Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71.

Kahu, E. R., Stephens, C. V., Leach, L., & Zepke, N. (2015). Linking academic emotions and student engagement: Mature-aged distance students' transition to university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 39(4), 481–497.

Kahu, E.R., Picton, C. & Nelson, K. (2019) Pathways to engagement: A longitudinal study of the first-year student experience in the educational interface, Higher Education.

Kuh, G. D., Cruce, T. M., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J., & Gonyea, R. M. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540–563 pp. 24.

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119–137.

MacCann, C., Fogarty, G. J., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2011). Coping mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 60–70.

Macfarlane, B. (2015). Student performativity in higher education: Converting learning as a private space into a public performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(2), 338–350.

Markwell, D. (2007) The challenge of student engagement, Keynote address at the Teaching and Learning Forum, University of Western Australia, 30-31 January 2007University of Western Australia, Perth, 30-31 January 2007, 1.

Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2009). Academic resilience and academic buoyancy: Multidimensional and hierarchical conceptual framing of causes, correlates and cognate constructs. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 353–370.

Masika, R., & Jones, J. (2016). Building student belonging and engagement: Insights into higher education students' experiences of participating and learning together. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(2), 138–150.

McCune, V. (2009) ‘Final year biosciences students’ willingness to engage: Teaching-learning environments, authentic learning experiences and identities’, Studies in Higher Education, Routledge, 34, 3, 347–361 [Online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597127

McMahon, B., & Portelli, J. P. (2004). Engagement for what? Leadership and policy in schools, 3(1), 59–76.

McMahon, B. & Portelli, J. (2012) The challenges of neoliberalism in education: Implications for student engagement. in Student Engagement in Urban Schools: Beyond Neoliberal Discourses, eds. B. McMahon & J. Portelli, Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, N.C., pp. 1-10.

Mirriahi, N., Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2018). Effects of instructional conditions and experience on student reflection: A video annotation study. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(6), 1245–1259.

Nakata, M. (2007). The Cultural Interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(Supplement), 7–14.

Payne, L. (2019). Student engagement: Three models for its investigation. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(5), 641–657.

Picton, C., Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). 'Hardworking, determined and happy': First-year students' understanding and experience of success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(6), 1260–1273.

Reay, D., Crozier, G., & Clayton, J. (2009). "Strangers in paradise"? Working-class Students in Elite Universities. Sociology, 43(6), 1103–1121.

Salamonson, Y., Andrew, S. & Everett, B. 2009, "academic engagement and disengagement as predictors of performance in pathophysiology among nursing students", Contemporary Nurse, vol. 32, no. 1-2, pp. 123-132.

Schunk, D. H., & Mullen, C. A. (2012). Self-efficacy as an engaged learner. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 219–235). Springer, New.

Schunk, D. H., & Mullen, C. A. (2013). Toward a conceptual model of mentoring research: Integration with self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 25(3), 361–389.

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: theory, research, and applications (3rd ed.). Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Scott, D., Hughes, G., Evans, C., Burke, P. J., Walter, C., & Watson, D. (2014). Learning Transitions in Higher Education. Palgrave.

Semetsky, I. (2006). Deleuze. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam.

Sirois, F., & Pychyl, T. (2013). Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(2), 115–127.

Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer, New.

Stenhouse, L. (1975). An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. Heinemann.

Taylor, C. A., & Harris-Evans, J. (2018). Reconceptualising transition to higher education with Deleuze and Guattari. Studies in Higher Education, 43(7), 1254–1267.

Thomas, L. 2012, Building Student Engagement and Belonging in higher Education at a Time of Change: final report from the What Works? Student Retention and Success programme., Paul Hamlyn Foundation, HEFCE, The Higher Education Academy and Action on Access, United Kingdom.

Thomas, L. (2016) Chapter 9 - Developing inclusive learning to improve the engagement, belonging, retention, and success of students from diverse groups" in Widening Higher Education Participation Elsevier Ltd, 135-159.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (2019). Learning better together. In Transitioning Students into Higher Education (pp. 13-24). Routledge.

Trowler, V. (2010). Student Engagement Literature Review. York.

Trowler, V. (2015). Negotiating contestations and "chaotic conceptions": Engaging "non-traditional" students in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 69(3), 295–310.

Trowler, V. (2017). Nomads in Contested Landscapes: Reframing Student Engagement and Non-traditionality in Higher Education. University of Edinburgh.

Trowler, V. (2019) Transit and Transition: student identity and the contested landscape of higher education, Habib, S. and Ward, M. (eds), Identities, Youth and Belonging, London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Trowler, V., Allan, R. L., & Din, R. R. (2019). 'To secure a better future': The affordances and constraints of complex familial and social factors encoded in higher education students' narratives of engagement. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 21(3), 81–98.

Trowler, V., Allan, R. L., Bryk, J. and Din, R. R. (2020) Penitent performance, reconstructed rumination or induction: Student strategies for the deployment of reflection in an extended degree programme. Higher Education Research & Development [Online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1712678.

van Dinther, M., Duchy, F., & Segers, M. (2011). Factors affecting students' self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 95–108.

Vuori, J. (2014). Student engagement: Buzzword or Fuzzword? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(5), 509–519.

Wayne, Y., Ingram, R., MacFarlane, K., Andrew, N., McAleavy, L., & Whittaker, R. (2016). A Lifecycle Approach to Students in Transition in Scottish Higher Education. Higher Education Academy.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81.

Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Belonging and the politics of belonging. Patterns of Prejudice, 40(3), 197–214.

Zepke, N. (2014) Student engagement research in higher education: Questioning an academic orthodoxy, Teaching in Higher Education.

Zepke, N. (2015) Student engagement research: Thinking beyond the mainstream, Higher Education Research & Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trowler, V., Allan, R.L., Bryk, J. et al. Pathways to student engagement: beyond triggers and mechanisms at the engagement interface. High Educ 84, 761–777 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00798-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00798-1