Abstract

Despite an almost endless list of possible study programs and occupational opportunities, high school students frequently focus on pursuing a small number of well-known study programs. Students also often follow gender-typical paths and restrict their attention to study programs in which the majority of students consists of same-gendered people. This choice pattern has far-reaching consequences, including persistent gender segregation and an undersupply of graduates in emerging sectors of the industry. Building on rational choice and social psychological theory, we argue that this pattern partly occurs due to information deficits that may be altered by counseling interventions. To assess this claim empirically, we evaluated the impact of a counseling intervention on the intended choice of major among high school students in Germany by means of a randomized controlled trial (RCT). We estimate the effect by instrumental variable estimation to account for two-sided non-compliance. Our results show that the intervention has increased the likelihood that participants will consider less well-known or gender-atypical study programs, particularly for high school students with lower starting levels of information. Supplementary analyses confirm that a positive impact on information seems to be one of the relevant causal mechanisms. These results suggest that counseling services have the potential to guide high school students to less gender-typical and well-known majors, possibly reducing gender segregation and smoothing labor market transitions after graduation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

High school students can pick from an almost endless list of possible college majors. Despite this abundance, a large share of high school students focus on a small number of occupational opportunities and the college majors that lead up to them. In a recent survey in countries participating in PISA, approximately 50% of high school students indicated that they expect to work in one of the 10 most well-known jobs. Among women, approximately 30% focus on only four jobs—medical doctor, psychologist, lawyer, and manager—as their first choice (OECD, 2019). The focus on these well-known jobs and the programs of study that allow them to be accessed (beaten paths) has severe consequences for the transition to the labor market and the economy as a whole. While there is an oversupply of students and graduates in well-known study programs, new and emerging professions face increasing difficulties in attracting qualified applicants (OECD, 2019). Consequently, leaving the beaten paths may smooth the transition to the labor market after graduation. Similarly, many students restrict their attention to gender-typical study programs where their own gender is in the majority (Chang & ChangTzeng, 2020; Morgan et al., 2013). In Germany, the share of females in some engineering majors is below 10%, while reaching nearly 90% in pedagogy (Destatis, 2019). This gender segregation in higher education is a major driver of gender inequality in later life, as male-dominated subjects offer more favorable employment prospects (Gerber & Cheung, 2008; Naess, 2020).

In sum, both choice patterns have undesirable consequences for society that reach well beyond the educational system itself. This raises the question of why these patterns emerge and whether they can be altered. In this paper, we build on rational choice (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Breen et al., 2014) and social psychological theory (Eccles, 2005; Festinger, 1954; Mannes et al., 2012; Ridgeway, 2011) and argue that both patterns can be attributed in part to a lack of information about available college majors and in part to insufficient knowledge about the individual’s own preferences and how well the various alternatives fit the individual.

We argue that in the absence of complete information, the disadvantages of leaving common behavioral paths (e.g., in terms of insecure employment prospects or study requirements) are apparent, while the benefits gained from, for example, choosing a career path that involves less common and/or gender-atypical majors, are uncertain. Consequently, students may avoid taking this risk, opting to stick to the more conventional behavioral patterns, even when other choices would better fit their personal preferences. In addition to the societal consequences outlined above, this may result in inferior educational outcomes, since students who choose a career path or major that does not fit their goals, interests, or personality type have lower choice satisfaction, consistency, and persistence within the chosen path (Holland, 1996; Rocconi et al., 2020; Suhre et al., 2007). The high dropout rates from beaten path programs suggest that simply following common behavioral choice patterns may be a poor decision for high school students (Neugebauer et al., 2019).

If these choice patterns emerge partly due to a lack of information, they may be weaker when information is more accurate and complete. We thus hypothesize that providing counseling services to high school students may lead them to consider less well-known or gender-atypical programs more frequently. To test this claim empirically, we assess the impact of a counseling intervention for high school students on the intended choice of major. The counseling intervention provides students with basic information on study programs as well as an assessment of their skills and interests complemented by individualized feedback. Broadly speaking, this intervention aims to direct students to college majors that best fit their personal skill profile and occupational preferences. Participants in the counseling workshop were in their penultimate or final year before graduating from high school. To achieve the highest degree of internal validity, we employ a field experiment that randomly assigns high school students to the treatment or control group (RCT) and estimate the treatment effect by instrumental variable regression to account for the possibility of endogenous non-compliance. In addition, we argue that the effect is not homogenous within the sample but varies systematically with the level of information students had prior to the workshop. Our results confirm that the workshop indeed increased the likelihood that high school students would consider gender-atypical and less well-known majors, particularly if the level of information they started with was low.

Our analyses contribute to previous research in numerous ways. At the most general level, they deepen our understanding of the determinants of choice of major in general and gender segregation in particular (Barone & Assirelli, 2020; Chang & ChangTzeng, 2020; Haas & Hadjar, 2020). Moreover, they build on and extend the evaluation literature that assesses the effectiveness of policy interventions for high school students. Previous research on similar counseling interventions (e.g., Le et al., 2016; Moore & Cruce, 2019; Turner & Lapan, 2005) has rarely employed experimental designs. Studies that have used random assignment have mostly focused on short info treatments of selected aspects of college enrollment, such as costs and benefits (Barone et al., 2017; Ehlert et al., 2017; Finger et al., 2020). To date, experimental evaluations of more comprehensive counseling services remain rare and therefore constitute an important gap in the literature. Finally, we assess a dimension of effect heterogeneity (starting level of information) that has largely been neglected by previous research and may enable future interventions to employ more effective targeting strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section develops a theoretical framework on the relationship between information, choice of major, and the role of counseling and reviews previous research in this field. The research design and methodology, including the counseling workshop under discussion, are then described, followed by a presentation of our results. The final section concludes with a summary and discussion for future research and policy-making.

Choice of major, information, and the role of counseling

Theoretical framework

According to rational choice theory, students weigh the costs and benefits of different options against each other when making educational choices (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Breen et al., 2014). When selecting between different possible majors, relevant financial parameters include direct costs, time and effort, the likelihood of succeeding, and employment prospects after graduation. Additionally, students seek to optimize the fit between their personal skills and interests and the skill profile of the respective major (Holland, 1959).

However, most of these parameters are subject to severe information deficits, particularly concerns about the fit between personal interests and the content of a particular study program (major-interest fit), since most high school students have only vague knowledge about the content of the study programs they are considering (Heublein et al., 2017). Consequently, students may end up making a decision they would not have made in the presence of complete information, as several parameters of the utility function are misestimated.

Generally, information deficits can lead to suboptimal choices in multiple ways since information updates affect each individual’s utility function differently. However, we argue that two patterns concerning the choice of major are more common when information deficits are high. First, a lack of information may partly explain why high school students often focus on a small number of well-known study programs, such as law, business, psychology, or medicine (beaten paths), as their first choice. This argument assumes that programs with a better interest-major fit may exist for several students, but the benefit of leaving the beaten paths is uncertain when only incomplete information about one’s own preferences as well as the exact content of alternative study programs is available. In contrast, the disadvantage of less secure employment prospects after graduation or the likelihood of failing in niche study programs may seem apparent. Consequently, some high school students may opt not to leave the (seemingly) safe harbor of well-known mass study programs, even though a different major would be a better fit for them personally. This argument is substantiated by social psychological theory, which holds that people tend to follow more common behavioral choice patterns (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Mannes et al., 2012) if uncertainty about available options is high.

Second, we argue that some information deficits tend to increase gender-typical choices. Information deficits are (partly) created through the general tendency of people to associate and gain information from (McPherson et al., 2001) and compare themselves to similar others (Festinger, 1954), such as same-gendered people. Considering that the choices and behavior of same-gender individuals can also function as a first or primary point of reference (Ridgeway, 2011), students likely possess detailed information on gender-typical choices but insufficient information on gender-atypical choices. Similarly, within expectancy-value theory (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000), Eccles (2005) argues that people do not choose from all available options but only from the most salient ones. Some options are not considered at all because of insufficient or inaccurate information. The crucial point is that these information deficits are gender-stereotyped (Eccles, 2005), i.e., students often possess information on gender-typical study programs and their contents but may have insufficient or inaccurate information on gender-atypical study programs. As a result, students may prematurely exclude gender-atypical majors even though they might better fit their interests and skill set (Eccles, 2005).

In sum, we argue that information deficits and inaccuracies increase the likelihood that students focus on well-known and gender-typical majors. At this point, the role of counseling comes into play. If a counseling intervention successfully decreases information deficits and dissolves information inaccuracies, the obstacles to leaving the beaten paths and/or considering gender-atypical choices are (partly) removed. Given that high school students may have difficulties finding and parsing reliable sources of information relating to the content of majors and how they fit them personally (Heublein et al., 2017), it seems reasonable to argue that targeted counseling and profiling interventions have the potential to tackle these problems. Correspondingly, we hypothesize that counseling interventions will increase the likelihood that less well-known study programs and gender-atypical majors will be considered.

In addition, we argue that the effect is not homogenous within the sample. The lower the starting level of information prior to the workshop, the higher the potential for improvement. In contrast, our argument becomes obsolete for students with very high levels of information due to ceiling effects. Therefore, we expect the effect on the intended choice of major to be stronger for students with lower levels of information prior to the intervention.

Related work

Previous literature on counseling interventions is characterized by strong heterogeneity in terms of the intervention type and the outcomes considered. The first group of studies administers counseling and profiling interventions aimed at fostering the major-interest fit, college enrollment as such, or academic performance. Turner and Lapan (2005) evaluated a computer-assisted intervention designed to increase nontraditional career interests, reporting positive effects for boys and girls. In contrast, Moore and Cruce (2019) did not find a positive impact of fit signals given to students on their planned major certainty. Domina (2009), Le et al. (2016), and van Herpen et al. (2020) evaluate large-scale counseling and college preparation programs from the USA and the Netherlands and find consistently positive effects on academic performance and the likelihood of enrolling in college, respectively. A second group of profiling interventions mostly focuses on the short-term effects of psychological constructs such as career decision-making self-efficacy (CDMSE) or career indecision. While Behrens and Nauta (2014) detected no effect on CDMSE when letting college students complete a self-assessment questionnaire (self-directed search, SDS; Holland, 1996), the majority of studies (for a review and meta-analysis see Whiston et al., 2017) report positive effects of interest inventories on CDMSE or related constructs. However, randomized designs are a rare exception among both groups of studies.

The third group of studies more frequently relies on RCTs while focusing on short info treatments, such as brief oral presentations or provision of information booklets or flyers (Ehlert et al., 2017; Loyalka et al., 2013), about the financial aspects of college majors such as costs or financial aid. These studies rely on the assumption that providing information about costs and benefits could affect college enrollment as such or the field of study, especially for students from nonacademic households (Ehlert et al., 2017; French & Oreopoulos, 2017; Hastings et al., 2015; Loyalka et al., 2013; Oreopoulos & Dunn, 2013). The effects tend to be positive but limited in size. For example, Barone et al. (2017) report positive effects on the likelihood of moving to longer or more ambitious fields of study, though the increase is, at 2.1 percentage points, slight.

In summary, previous research has revealed important insights for guiding high school students to suitable majors. Both comprehensive counseling and profiling interventions as well as short info treatments have the potential to improve the transition from high school to college. At the same time, several gaps in the literature remain. Most importantly, few studies have investigated the impact of counseling and profiling interventions by means of RCTs. Those that have employed RCTs have mostly focused on info treatments of short duration (20–60 min). Correspondingly, little evidence exists on the impact of comprehensive counseling and profiling interventions that meet the highest methodological standards (especially random treatment assignment). Moreover, the analysis of effect heterogeneity has mostly focused on effect differences with respect to socioeconomic background. Further moderators, such as the starting level of information, have largely been neglected. In this regard, our analysis extends the previous literature at both the substantive and methodological levels.

Methodology

Research design and target group

Students who were between 6 and 18 months before graduating high school and planned to go on to university were invited to participate in the study. Participants were actively recruited from high schools in the areas surrounding two large German cities, resulting in a sample of 725 voluntary participants. Workshops were carried out by the department for student services of the two universities. The recruiting strategy was similar to that usually employed for workshops offered by the department for student services (promotion of the workshop via high schools or during campus days, among others). Consequently, the resulting sample is not representative of all high school students but very similar to groups usually entering university counseling interventions in Germany.

To register for the study, participants needed to take part in the first survey, where pretreatment and time-invariant covariates were gathered. At the end of the first survey, participants were randomly assigned to the treatment group, the members of which were invited to the counseling workshop, or to the control group, whose members participated in a lottery. After the workshop took place, the participants were invited to take part in the second survey of the study, during which all outcome variables were measured again. The time between the first and second survey was between 3 and 6 months for most participants and was held constant between the treatment and control groups to avoid collinearity between treatment status and calendar time.

A total of 607 students participated in the second survey, resulting in a relatively high response rate of 83.72%. This rate was achieved by reminding participants multiple times via e-mail, SMS, and telephone calls to fill out the second survey. The 16.28% who did not respond mostly consisted of students with invalid telephone numbers or those who never answered the phone. As telephone numbers were collected before the randomization, there is no reason to believe that this is correlated with treatment status, thus refuting concerns about endogenous panel attrition (for an in-depth discussion of possible biases due to panel attrition and item-nonresponse, see the robustness section). A total of 574 participants provided complete information on all relevant variables and were used for the analyses (see Table A1 for summary statistics).

The counseling workshop

The intervention is a full-day university guidance workshop. Prior to attending the workshop, students were asked to do an online self-assessment test made available by the German Federal Employment Agency. The test assesses both cognitive and noncognitive skills as well as vocational interests. During the workshop, participants received individual feedback from professional counselors about study opportunities that could fit their skills and preferences. The workshop also provided information on different kinds of study programs (e.g., university vs. university of applied sciences) and fields of studies as well as sources and strategies for gathering further information. Afterward, an enrolled student shared his or her own experience with studying at university. At the end of the workshop, the participants were asked to write out everything they had learned about themselves and their plans for the future. The design of the workshop thus followed previous work on critical ingredients for successful counseling intervention (Brown et al., 2003). In total, 28 counseling workshops with an average of nine participants each were conducted as part of the experiment.

To put this into the context of our theoretical argument, we expect this workshop to affect the decision process of participants in several ways. First, we hypothesize that the workshop increases students’ level of information concerning possible study opportunities as well as their ability to gather additional information about available majors. Second, online self-assessment with individual feedback is intended to help students increase awareness of their individual skills and occupational preferences, enabling them to identify college majors with a better major-interest fit. Finally, the workshop conveys the general notion that this major-interest fit is the most important parameter for their choice. As a result, students should become more inclined to focus on their personal preferences rather than following the behavior of others in general or the behavior of people of the same gender in particular when choosing a college major.

Data and variables

Our primary outcome is students’ intended choice of major. The intention to enroll in a gender-atypical major and a major that is off the beaten path (non-beaten path) are dichotomous outcomes, coded from an open question, in which students were asked to name up to five majors they were considering. The answers were coded according to the classification of study programs by the German Office of Statistics (Destatis, 2020). If at least one of the majors listed was gender-atypical, the answer was coded as 1, and 0 otherwise. The same procedure is used for coding the non-beaten path. That is, if students mentioned a study program outside of medicine, psychology, law, or business, they were considering a non-beaten path and coded as 1. This definition seems the most plausible from a theoretical point of view. While it may also be possible to count the number of non-beaten path or gender-atypical study programs in the choice set, we argue that mentioning only one particular study program reflects a greater certainty that it is the most suitable option. Therefore, the dichotomous measurement seems more accurate than the numeric measurement.

Gender-atypical majors are defined based on the distribution of enrolled males and females in the respective study program. We define a gender-atypical major as one in which the share of students from the opposite gender is at least 60%. For example, a woman who intends to enroll in a major in which at least 60% of the enrolled students are male intends to study a gender-atypical major. To see whether the results are robust to different threshold specifications, we also varied the threshold to 65% and 70% (see robustness section). The definition of a non-beaten path is based on the distribution of intended study choices within our sample. Four study programs listed within the choice sets were by far the most common: medicine (mentioned by 20.55%), business and economics (29.93%), law (19.31%), and psychology (22.48%). All other fields of study were mentioned by at most 10% of the participants, implying that the four most common fields have an outstanding position. This pattern is broadly consistent with that found in representative surveys.

As outlined in the theory section, we argue that a change in one’s intended choice may partly be due to an increase in the amount of information. Correspondingly, we conduct supplementary analyses concerning the impact on the level of information. This includes (1) self-appraisal (i.e., being aware of one’s own skills and preferences), (2) the ability to gather information, and (3) goal selection (i.e., being able to select between different majors). However, measuring these dimensions of the actual level of information is not straightforward. We therefore follow previous research that has often relied on psychometric scales such as CDMSE, which measure confidence in one’s own knowledge and decision-making competence. Assuming that students can estimate their own level of information with some reliability, CDMSE can be treated as a proxy for the actual level of information.

We slightly adapted the CDMSE short-form scale (Betz et al., 1996) to more precisely measure what the workshop is intended to affect. It includes the three outlined subdimensions with three items each. In each question, respondents are asked to rate their ability to perform a specific task on a scale ranging from “no confidence at all” (1) to “complete confidence” (5). We calculated the mean over all subscales (CDMSE-total) as well as the mean of each subscale separately. The scales show high consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging between 0.71 and 0.86.

To increase the efficiency of our treatment effect estimations, we included pretreatment outcomes and time-invariant covariates in our analyses (Imbens & Rubin, 2015). These include gender, parental education level (whether both parents have a university degree or not), household composition (living with siblings/with both parents), age, average grades in high school, study aspiration of schoolmates, and parents’ ambition (their desire for their child to have a university vs. vocational education). We also included a variable indicating when students started to gather information about study opportunities (before upper-secondary education, during the last school year, during this school year, not yet). The last two categories were combined due to the low number of observations in the highest category. Finally, we present information on both treatment assignment and treatment participation as reported by the counselors to the research team.

Table A1 provides summary statistics for all variables used in the analyses. As stated in the previous section, the sample is not representative of the population of German students in this age group. Workshops of this type are usually offered to a self-selected rather than representative group. Therefore, our study group is similar to students who usually enter such workshops, as opposed to a representative sample of high school students. Our sample consists of a larger share of female students, students from academic households, and high-achieving students (in terms of grades), mirroring the pattern often observed in such interventions. Consequently, the results tend to generalize to similar, voluntary workshops but might be different for large-scale interventions that cover all or a representative set of students.

Estimation technique and robustness checks

In RCTs, treatment assignment is exogenous by design. However, actual participation might not be random in case of non-compliance. In our case, this means that, i.e., some participants assigned to the treatment group did not appear in the workshops and vice versa. Using treatment status as regressor would therefore lead to biased results if non-compliance is not random. The econometric literature mostly discusses two solutions for non-compliance: intent-to-treat (ITT) and instrumental variable (IV estimation; (Athey & Imbens, 2017; Imbens & Rubin, 2015). ITT estimates the effect of treatment assignment rather than actual treatment participation, which is unaffected by non-compliance. To facilitate the efficiency of the estimation, we estimate the ITT effect by means of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with robust standard errors including all covariates discussed in the previous section and the respective pretreatment outcome. Subsequently, we estimate the treatment effect of actual participation by IV estimation, with exogenous treatment assignment being used as instrumental variable for actual treatment (this identifies the local average treatment effect on compliers; see Imbens & Rubin, 2015 for an in-depth discussion). For the sake of transparency, we present results from both estimations. To further substantiate the robustness of our results, we perform a wide range of alternative estimations (see robustness section).

Results and discussion

Main results and effect heterogeneity

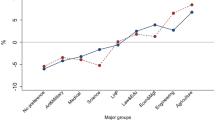

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the results from the OLS-ITT and IV regressions, which estimate the treatment effect on our primary outcomes plus the supplementary analyses on CDMSE. As non-compliance in our sample is rather small (12.14%), the two estimation techniques lead to very similar results. Point estimates and confidence intervals of the IV regressions are further displayed in Graph 1. The results point to the expected direction but are somewhat mixed in terms of statistical significance. Focusing on the intended choice of major, having a non-beaten path in the choice set is not significantly affected (t = 1.16 (ITT)/z = 1.17 (IV)), while considering a gender-atypical major is significant at the 10% level (t = 1.85/z = 1.87). In the linear IV model, the treatment coefficient represents a 6.36 percentage point increase in the probability of considering a gender-atypical major. The treatment effect is slightly smaller within the ITT estimation (4.91).

Beyond the treatment effect itself, it is interesting to see that the start of gathering information strongly predicts the consideration of a non-beaten path major. This substantiates the argument that the decision to take the beaten path may result from insufficient knowledge about suitable alternatives. Those who started looking for information before commencing their upper-secondary education were 15.92 percentage points more likely to consider a non-beaten path major than those who started during this school year/not yet (IV estimation). At the same time, we do not see a statistically significant effect of this variable on gender-atypical choice. While the treatment effect of the counseling intervention is medium strong, the starting point of independent information gathering seems to be of less importance for gender-atypical choice. Possibly, gender-atypical study programs were rarely considered during the independent information gathering, implying that exogenous sources of information do matter for gender-atypical choice, whereas independent information gathering does not.

In addition to the impact on choice of major, we looked at the treatment effect on CDMSE. Among the three subscales of level of information, one out of three (gathering information) is significant at the 5% level (t = 2.02/z = 2.05). The two other scales are clearly insignificant, and the point estimates are close to zero. Considering the measurement issues with these outcomes, it is worth noting that the strong correlation between CDMSE and the starting level of gathering information can be seen as an implicit validation of the CDMSE measure as a proxy for the level of information, as longer periods of information gathering should result in a higher level of information.

As outlined in the previous sections, the treatment effect may not be homogeneous among participants, but stronger for those who start with lower levels of information. In the next step, we therefore interact the treatment with the starting level of information, defined as the self-assessed level of information (CDMSE) at wave 1, for our two main outcomes.

The results are summarized in Table 3 and visualized in Graph 2. The regression table only displays coefficients from the interaction term and base variables, but the interaction models include the same set of covariates as depicted in Tables 1 and 2. As Table 3 indicates, there is no visible interaction for considering a gender-atypical study program. In contrast, there is a fairly strong interaction for considering a non-beaten path. Graph 2 displays the estimated effects at different levels of the interaction variable and reveals that the treatment effect is strong and significant at the 5% level for those at the bottom of the CDMSE distribution but becomes insignificant once the starting level of information rises above a certain point. For the sake of robustness, we also repeated the interaction analysis with an alternative measure of starting level of information, namely when students started gathering information on tertiary education. The results (see Table A2) corroborate the finding that for low starting levels of information the treatment effect on considering a non-beaten path is highest and decreases as the information level increases. Similarly, there is once again no substantive or significant interaction between starting level of information and the treatment for the consideration of a gender-atypical study program.

This finding reinforces the argument that the focus on well-known study programs may partly result from insufficient knowledge about possible alternatives but may be altered by interventions that deliver this information.

Discussion

These results reveal an interesting picture. Broadly speaking, the effects tend to confirm the theoretical expectations. Workshop participation indeed increases the likelihood that high school students will consider less well-known and/or gender-atypical majors. This finding suggests that counseling services may be a promising tool for encouraging students to engage in gender-atypical study programs, thereby weakening gender segregation in higher education. Similarly, such interventions seem to widen students’ horizons, especially for those who are uninformed, and lead them away from beaten paths in the direction of otherwise less frequently considered study programs. This may contribute to both a better major-interest fit and better educational outcomes, as well as improved post-education matching in certain sectors of the labor market. While it is hard to assess the causal mechanisms in such encompassing treatments, the positive effect on one CDMSE subscale suggests that information could be a key factor in this process. Consistent with our expectations, the effect is not homogenous within the sample but appears to be particularly strong for students with lower levels of information. This adds to discussions on the effect of the heterogeneity of such interventions and reinforces that targeting may be highly relevant to their effectiveness.

At the same time, the results are not absolutely clear-cut. The average treatment effect is only significant in the case of gender-atypical choices, while the interaction with the information variables is only visible for considering non-beaten paths. While this puzzle cannot be solved completely, the much stronger prediction of the starting level of information for non-beaten path choices leads to the conclusion that the information argument accounts more heavily for less well-known study programs than for gender-atypical choices. This finding appears plausible, as gender segregation is driven by many more factors that are not affected by the counseling intervention. In sum, these results show that counseling services have the potential to alter the intended choice of major and that finding the right target group can make a larger difference, while additional research in this area is needed to arrive at more definite conclusions.

From a theoretical point of view, these results reinforce the notion that information (deficits) matters for the decision-making process of high school students. This conclusion becomes apparent due to the strong correlation between the starting level of information and considering non-beaten path majors. The finding that providing exogenous sources of information by means of counseling interventions increases the likelihood of considering less well-known or gender-atypical study programs further substantiates this notion. At a more abstract level, this suggests that information deficits should be considered in theoretical approaches aimed at predicting and understanding students’ field of study decisions. While these findings may be important for multiple theoretical fields, they matter most for rational choice theory, as incomplete information about available options undermines the process of rationally weighing the costs and benefits against each other. Findings on choice of major that seem to contradict the basic assumption that students make rational choices might therefore be explained by information deficits that lead to misestimation of the different parameters that make up the utility function.

Robustness checks and methodological notes

We perform various robustness checks and sensitivity analyses. Most importantly, we assess biases that could occur due to endogenous panel attrition, i.e., if dropout between the treatment and control groups is asymmetric. For example, if particularly motivated participants from the control group refuse to answer the second survey, the treatment assignment would be confounded in the analysis sample. While asymmetric attrition on unobservables cannot be completely ruled out, we assess attrition issues in three ways.

First, we run a series of regressions where participation in the second survey is the outcome and treatment, a wave 1 outcome or covariate and their interaction are the independent variables. Second, we regress each pretreatment outcome (measured at wave 1) and covariate on the treatment assignment indicator, attrition indicator, and their interaction (for a similar approach, see Wang et al., 2016). In both cases, there are hardly any significant interactions (Tables A3-A5), implying that there is no observable asymmetric attrition. Finally, we perform a multivariate test for covariate imbalance by regressing treatment assignment on all covariates for those who participated in both waves. The results (Table A6) show an explained variation of treatment assignment of almost zero (R2 < 0.02). These tests show that the attrition between treatment arms is fairly symmetric, making attrition bias less likely in our sample. Still, unobserved endogenous attrition cannot be ruled out completely. The calculation of Lee bounds (Lee, 2009) shows that the estimated treatment effects might get insignificant for the lower bound scenario (the calculated bounds are [0.0090966: 0.1267873] for the non-beaten path and [− 0.0058021: 0.0823596] for the gender-atypical study choice). However, it should be considered that Lee bounds perform a correction assuming the most extreme possible asymmetric attrition, which seems like a hypothetical scenario in our case. Nonetheless, we cannot completely rule out that our results are biased by endogenous selection, but all tests conducted strongly refute this concern.

Second, we rerun the estimation for all outcomes by handling attrition in four different ways. We (1) run more parsimonious models that only include the treatment assignment indicator and pretreatment outcome, (2) run all models without dropping observations that have missing information on other variables, and (3) conduct multiple imputation for all covariates and (4) for all missing outcomes. The results remain similar for all outcomes and all four modes of handling missing data (see Tables A7–A12).

Two further issues at the design level include possible spillover effects as well as substitute guidance counseling that students in the control group could have received through different means. While both mechanisms might bias treatment effects, they can quite safely be assumed to bias estimated effects downward. In this regard, the outlined treatment effects tend to represent lower bounds and would be larger in the absence of these possible biases.

Concerning the estimation itself and the coding of the variables, we replicate the estimations for our main outcomes and supplementary outcomes with bootstrap estimation (see Table A13). We further estimate the treatment effect of our main binary outcomes with bivariate probit (see Table A14) and consider different threshold for when a study program is considered gender atypical (Table A15). The results rarely differ compared to the baseline specification. Noteworthy differences are that the effect on considering gender-atypical majors gains significance at the 5% level in the bivariate probit model and that the treatment effect decreases when the threshold for gender-atypical majors is increased. Overall, the high number of robustness checks confirms that the results are relatively robust to different measurements of the variables or changes in the estimation technique. At the same time, we wish to point out that ignoring non-compliance can markedly change the results (see Table A16). The treatment effects tend to get more positive and significant, suggesting that treatment effects are upward biased due to positive selection into actual participation.

Finally, we want to consider the problem of multiple hypothesis testing. In this paper, we look at two primary outcomes (gender-atypical and non-beaten path study program) and one supplementary outcome (CDMSE) composed of three subscales. By looking at multiple outcomes using the same experiment, the likelihood of a type I error, i.e., falsely rejecting a null hypothesis, increases. Although multiple hypothesis correction methods are not commonly employed in similar higher education field experiments (e.g., Barone et al., 2018; Ehlert et al., 2017; Hastings et al., 2015; Loyalka et al., 2013), they can be considered best practice when the objective is to keep the possibility of a type I error as low as possible. When correcting for multiple hypothesis testing (see Tables A17 and A18 for two and six outcomes, respectively), using the Romano and Wolf (Clarke et al., 2020) procedure, all treatment coefficients become insignificant. This is not surprising, since the necessary power to uncover statistically significant effects increases greatly when correcting for multiple hypothesis testing. Similarly, the likelihood of committing a type II error, i.e., falsely keeping a null hypothesis, also increases. As such, correcting for multiple hypothesis testing comes with its own caveats (for a general discussion, see Streiner, 2015) and we believe that the best way to ascertain the validity of the experimental results is through replication.

Conclusion

This paper was inspired by the observation that high school students often focus on gender-typical and well-known study programs. Due to the undesirable consequences of these patterns at the individual and aggregate levels, this tendency prompted us to ask why these patterns emerge and whether policy interventions may weaken them. Building on a theoretical framework that combines rational choice and social psychological theory, we have argued that these patterns partly result from information deficits concerning college majors and the respective major-interest fit and may therefore be reduced by counseling interventions. The results from our field experiment with random assignment tend to confirm this argument. The workshop indeed seems to encourage students to consider less well-known and/or gender-atypical majors, particularly if the level of information they are starting with is low. At the same time, the results are somewhat mixed, and not all of the average treatment effects and interactions reach significance. From a theoretical point of view, our results confirm that information deficits seem to contribute to the existence or at least the strength of the observed choice patterns, which is of particular importance for further development of rational choice approaches in education research. The replication of the results with naïve OLS estimation reinforces both the need to consider and accurately address non-compliance and the general need for random assignment in future evaluations.

While these results inform higher education policy-making and contribute to previous research in this field in many regards, they also have limitations and raise at least three questions that remain to be answered. First, more research is needed to enable general conclusions to be drawn on the research questions addressed in this paper. On the one hand, the results are somewhat mixed and leave some room for interpretation. On the other hand, it remains subject to future research to confirm to what extent these findings generalize to other contexts (external validity). In fact, our interaction analyses suggest that treatment effects may (among others) differ with respect to the access to and quality of information that students possess prior to the intervention and may differ for other target groups or institutional contexts. The results might therefore differ in large-scale interventions targeted at all or a representative sample of students. Second, the effect size was rather moderate, suggesting that more intense treatments may be needed to achieve stronger effects, especially in the long run. The results therefore encourage further research on higher-intensity interventions to assess whether they yield more extensive effects. Finally, mirroring previous research, our analyses have focused on intended rather than actual study choice. Whether this short-term effect on the intended choice of major translates into long-term effects on actual choice remains subject to future research. A related and as yet open question is whether students are actually better off leaving the gender-typical and beaten paths in regard to their level of achievement in higher education and their postgraduate labor market outcomes. While this is a limitation of our results, a stronger focus on long-term effects could be beneficial for this body of literature as a whole, as research on the long-term effects of such interventions remains in its infancy.

Data availability

The data were collected from students and are not publicly available to ensure the privacy of our participants.

Code availability

The analysis was conducted with Stata 16. The code can be made available upon request.

Change history

28 February 2022

The original version of this paper was updated to add the missing compact agreement Open Access funding note.

References

Athey, S.; Imbens, G. W. (2017): Chapter 3 - The econometrics of randomized experiments. In Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee, Esther Duflo (Eds.): Handbook of Economic Field Experiments : Handbook of Field Experiments, vol. 1: North-Holland, pp. 73–140.

Barone, C., & Assirelli, G. (2020). Gender segregation in higher education: An empirical test of seven explanations. Higher Education, 79(1), 55–78.

Barone, C., Schizzerotto, A., Abbiati, G., & Argentin, G. (2017). Information barriers, social inequality, and plans for higher education: Evidence from a field experiment. European Sociological Review, 33(1), 84–96.

Barone, C., Schizzerotto, A., Assirelli, G., & Abbiati, G. (2018). Nudging gender desegregation: A field experiment on the causal effect of information barriers on gender inequalities in higher education. European Societies, 33(1), 1–22.

Behrens, E. L., & Nauta, M. M. (2014). The self-directed search as a stand-alone intervention with college students. The Career Development Quarterly, 62(3), 224–238.

Betz, N. E., Klein, K. L., & Taylor, K. M. (1996). Evaluation of a short form of the career decision-making self-efficacy scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 47–57.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305.

Breen, R., van de Werfhorst, H. G., & Jæger, M. M. (2014). Deciding under doubt: A theory of risk aversion, time discounting preferences, and educational decision-making. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 258–270.

Brown, S. D., Ryan Krane, N. E., Brecheisen, J., Castelino, P., Budisin, I., Miller, M., & Edens, L. (2003). Critical ingredients of career choice interventions: More analyses and new hypotheses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(3), 411–428.

Chang, D.-F., & ChangTzeng, H.-C. (2020). Patterns of gender parity in the humanities and stem programs: The trajectory under the expanded higher education system. Studies in Higher Education, 45(6), 1108–1120.

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621.

Clarke, D., Romano, J. P., & Wolf, M. (2020). The Romano-Wolf multiple-hypothesis correction in stata. The Stata Journal, 20(4), 812–843.

Destatis. (2019). Genesis-online datenbank: Studierende: Deutschland, semester, nationalität, geschlecht, studienfach. Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=21311-0003&levelindex=1&levelid=1585738630500

Destatis. (2020). Bildung und Kultur: Studierende an Hochschulen. Wintersemester 2019/2020 (Fachserie 11 Reihe 4.1). Statistisches Bundesamt.

Domina, T. (2009). What works in college outreach: Assessing targeted and schoolwide interventions for disadvantaged students. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31(2), 127–152.

Eccles, J. S. (2005). Studying gender and ethnic differences in participation in math, physical science, and information technology. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2005(110), 7–14.

Ehlert, M., Finger, C., Rusconi, A., & Solga, H. (2017). Applying to college: Do information deficits lower the likelihood of college-eligible students from less-privileged families to pursue their college intentions? Evidence from a field experiment. Social Science Research, 67, 193–212.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

Finger, C., Solga, H., Ehlert, M., & Rusconi, A. (2020). Gender differences in the choice of field of study and the relevance of income information. Insights from a field experiment. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 65, 100457.

French, R., & Oreopoulos, P. (2017). Behavioral barriers transitioning to college. Labour Economics, 47, 48–63.

Gerber, T. P., & Cheung, S. Y. (2008). Horizontal stratification in postsecondary education: Forms, explanations, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 299–318.

Haas, C., & Hadjar, A. (2020). Students’ trajectories through higher education: A review of quantitative research. Higher Education, 79(6), 1099–1118.

Hastings, J., Neilson, C. A., & Zimmerman, S. D. (2015). The effects of earnings disclosure on college enrollment decisions. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers, No. w21300.

Heublein, U [U.], Ebert, J., Hutzsch, C., Isleib, S., König, R., Richter, J., & Woisch, A. (2017). Zwischen Studienerwartungen und Studienwirklichkeit: Ursachen des Studienabbruchs, beruflicher Verbleib der Studienabbrecherinnen und Studienabbrecher und Entwicklung der Studienabbruchquote an deutschen Hochschulen (Forum Hochschule 1 | 2017). Hannover. DZHW.

Holland, J. L. (1959). A theory of vocational choice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 6(1), 35–45.

Holland, J. L. (1996). Exploring careers with a typology. What we have learned and some new directions. American Psychologist, 51(4), 397–406.

Imbens, G. W., & Rubin, D. B. (2015). Causal inference in statistics, social, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Le, V.-N., Mariano, L. T., & Faxon-Mills, S. (2016). Can college outreach programs improve college readiness? The case of the college bound, St. Louis Program. Research in Higher Education, 57(3), 261–287.

Lee, D. S. (2009). Training, wages, and sample selection: Estimating sharp bounds on treatment effects. The Review of Economic Studies, 76(3), 1071–1102.

Loyalka, P., Song, Y., Wei, J., Zhong, W., & Rozelle, S. (2013). Information, college decisions and financial aid: Evidence from a cluster-randomized controlled trial in China. Economics of Education Review, 36, 26–40.

Mannes, A. E., Larrick, R. P., & Soll, J. B. (2012). The social psychology of the wisdom of crowds. In Joachim I. Krueger (Ed.), Frontiers of social psychology. Social Judgment and Decision Making. Psychology Press.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444.

Moore, J. L., & Cruce, T. M. (2019). The impact of an interest-major fit signal on college major certainty. Research in Higher Education.

Morgan, S. L., Gelbgiser, D., & Weeden, K. A. (2013). Feeding the pipeline: Gender, occupational plans, and college major selection. Social Science Research, 42(4), 989–1005.

Naess, T. (2020). Master’s degree graduates in Norway: Field of study and labour market outcomes. Journal of Education and Work, 33(1), 1–18.

Neugebauer, M., Heublein, Ulrich, U., & Daniel, A. (2019). Studienabbruch in deutschland: Ausmaß, ursachen, folgen, präventionsmöglichkeiten. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22(5), 1025–1046.

OECD. (2019). Dream jobs? Teenagers’ career aspirations and the future of work. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved March 5, 2020, from https://www.oecd.org/education/dream-jobs-teenagers-career-aspirations-and-the-future-of-work.htm

Oreopoulos, P., & Dunn, R. (2013). Information and college access: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(1), 3–26.

Ridgeway, C. L. (2011). Framed by gender: How gender inequality persists in the modern world. Oxford University Press.

Rocconi, L. M., Liu, X., & Pike, G. R. (2020). The impact of person-environment fit on grades, perceived gains, and satisfaction: an application of Holland’s theory. Higher Education.

Streiner, D. L. (2015). Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: The multiple problems of multiplicity-whether and how to correct for many statistical tests. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102(4), 721–728.

Suhre, C. J. M., Jansen, E. P. W. A., & Harskamp, E. G. (2007). Impact of degree program satisfaction on the persistence of college students. Higher Education, 54(2), 207–226.

Turner, S. L., & Lapan, R. T. (2005). Evaluation of an intervention to increase non-traditional career interests and career-related self-efficacy among middle-school adolescents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(3), 516–531.

van Herpen, S. G. A., Meeuwisse, M., Hofman, W. H. A., & Severiens, S. E. (2020). A head start in higher education: The effect of a transition intervention on interaction, sense of belonging, and academic performance. Studies in Higher Education, 45(4), 862–877.

Wang, H., Chu, J., Loyalka, P., Xin, T., Shi, Y., Qu, Q., & Yang, C. (2016). Can social-emotional learning reduce school dropout in developing countries? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35(4), 818–847.

Whiston, S. C., Li, Y., Goodrich Mitts, N., & Wright, L. (2017). Effectiveness of career choice interventions: A meta-analytic replication and extension. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 175–184.

Wigfield, & Eccles. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marita Jacob, Janina Beckmann and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received funding from the BMBF (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung) Funding Priority – “Academic success and dropout phenomena” (funding code (FKZ): 01PX16004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The experiment was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Management, Economics and Social Sciences of the University of Cologne.

Consent to participate

Informed consent of the participants was obtained prior to the experiment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Piepenburg, J.G., Fervers, L. Do students need more information to leave the beaten paths? The impact of a counseling intervention on high school students’ choice of major. High Educ 84, 321–341 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00770-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00770-z