Abstract

This article examines the effect of location on the development of new universities. The study was conducted in seven new higher education institutions (HEIs) established in India during 1996–2008. I collected the data by conducting semi-structured interviews with 73 faculty members in the HEIs and from official documents, media reports and opinion pieces about the HEIs. Using the conceptual framework of path dependency, I investigated the tensions and challenges faced by the HEIs in their initial years. I find the placement of the HEIs in their respective locations to be a contingent event that can make the development of HEIs path dependent. I find that the initial conditions and decisions of the HEIs were influenced by the location and led to reactive sequential events in their initial years with effects that were hard to shake off, making their development path dependent. I show that having to develop their infrastructure and constrained by resources, the HEIs started their academic programmes first, followed by their research activities, and outreach and regional engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past few decades, several countries, such as China, India, Russia and Singapore, have established new universities at the top end of their stratified higher education systems. These universities are aspirational, entrepreneurial, innovative and have access to the essential resources and networks to become leading national or global universities (Altbach et al. 2018; Marginson 2016). The rise of such universities has gained so much attention that global rankings like the QS and THE World University Rankings have specialised rankings for universities that are younger than 50 years. This article aims to provide an understanding about the development of such new universities in their initial years.

The main question that I investigate in this article is, how does the location of new universities shape their development in the initial years? The initial years of new universities is critical for them to chart new paths, generate momentum and cement their position in the national higher education system. During this period, they take their most import decisions that lay their foundations for entering into higher education competition and developing their reputation (Perkin 1969; Stensaker and Benner 2013). They can achieve a lot more during this period than their established counterparts can in the same period (Altbach et al. 2018). Their location is significant to this development since in absence of certain specific characteristics of the local environment, their development can become ritualistic, making them more ambiguous, eventually dislodging them from their starting position (Stensaker and Benner 2013). Thus, the eventual positioning of new universities can be shaped by their considerations of their location in the initial years (Brennan et al. 2018; Harris and Holley 2016).

A small number of studies on new universities claim that their location and considerations for the surrounding region influence their uniqueness (Huisman et al. 2002), trajectory (Stensaker and Benner 2013) and pace of development (Altbach et al. 2018). Other studies (Goddard and Puukka 2008; Weerts 2014)—although not specific to new universities—provide credence to these claims by showing that the local context can help universities in image building, attracting faculty and increasing student enrolment, and by providing funding opportunities and social capital support. However, the nature of development of new universities in the initial years varies from the established ones. Sans the inertia and rigid academic boundaries of established universities, they experiment with new ideas of teaching and research, launch innovative academic programmes and develop distinctive features (Altbach et al. 2018). Their initial years is thus a period of change and building up of momentum and is noticeably different from the period of sustaining the change in a steady state (Clark; 2003).

The development of new universities in the initial years is steered by the decisions and activities of a small number of individuals instead of a coordinated strategic approach (Clark 1998). Their nature of development during this period can be described as “evolutionary” that is emergent or unintentional (Mezias and Glynn 1993). Such development is summoned from within, not as much a response to external demands and expectations, and precedes their development of culture, reputation and management ideals. It has unclear boundaries, individually motivated, opportunistic and interactive in development. Thus, I analyse the development of new universities as an evolutionary path, on which they traverse from one point, starting from scratch, on this path to another. These decisions and activities get institutionalised over time as policies, structures and management practices. I investigate how the location of new universities influences their decisions and activities and shape their evolutionary development path.

The context for this study: the Institutes of National Importance in India

The Institutes of National Importance (INIs) are a cadre of national-level universities in India that are established and funded by the government and specialise in a single disciplinary area of study. Started in the 1950s, the established INIs are amongst the few research-intensive universities in India and have grown to be highly reputed and selective. They attract the best faculty and students in their respective disciplines and are often the only universities from India to feature in global higher education rankings. The government rapidly increased the number of INIs from nearly 10 in 1995 to 101 in 2018. One of the key features of this expansion is that many of the new INIs were situated in rural and semi-urban locations. This study was conducted on the new INIs in India.

Single disciplinary universities, like the INIs, have gained popularity in recent times in Asian countries, such as Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea, as a model to establish new universities. However, the growth of INIs differs from their Asian counterparts on few dimensions. First, unlike their Asian counterparts that have grown with the combined support of private philanthropy and government (Altbach et al. 2018), the new INIs are entirely funded and governed by the government. Second, the INI model has been replicated across several disciplines, such as management, medicine and technology, accommodating the idiosyncrasies of each discipline. Third, there are multiple INIs in each discipline in various locations. They follow a common admission process and comply to several standardised norms and policies prescribed by the government. However, each INI is governed and managed independently and have their own reputation and positioning in the Indian higher education. Thus, the new INIs are likely to experience the legacy of their established and more reputed counterparts. Given the above, this study can provide insights into the growth of new single disciplinary universities as a model of expansion in other higher education systems.

Using path dependency theory for analysis

Path dependency is characterised by nonergodicity—an inability to shake free of history (Martin and Sunley 2006). Its identification involves tracing back the current state to a set of historical events and decisions and showing how these events and decisions themselves are contingent occurrences (Garud et al. 2010; Martin and Sunley 2006). Contingent occurrences are those that were not expected to take place and cannot be explained based on theoretical conditions or what is already known about the institution. They can only be explained by an accident or chance and have substantive lingering effects on the future paths of institutions (Mahoney 2000; Sydow et al. 2009).

One type of analysis of path dependency considers sequence of events as self-reinforcing, i.e. initial setups in a direction induce further movements in the same direction such that there are increasing returns and it becomes difficult to reverse the direction. These paths have critical junctures that are adoption of a particular institutional arrangement from amongst two or more alternatives (Martin, 2010). The other type of analysis of path dependency includes reactive sequences that are chains of temporally ordered and causally connected events. In a reactive sequence, each event in a sequence is both a reaction to antecedent events and a cause of subsequent events. Whereas self-reinforcing sequences reinforce early events, reactive sequences transform or may even reverse early events. Institutions that are path dependent can get locked-in to a particular trajectory or situation that is sub-optimal or inefficient (Sydow et al. 2009).

Universities can be considered as path dependent in the usual sense that their directions for future development are foreclosed or inhibited by decisions taken in past (Stensaker et al.; 2012). Studies on path dependency (Garud et al. 2010; Martin and Sunley 2006; Sydow et al. 2009) indicate that various effects such as learning effects (i.e. accumulated skills and expertise of faculty members), complementary effects (i.e. synergies between activities of the region with those of the universities), and coordinate effects (i.e. coordination between the university and the region that develops specific routines and rules) may result in universities getting locked-in with their region. However, for new universities with less academic standing, getting locked-in with the region will lead to strategic inertia with few alternative development paths (Stensaker and Benner 2013). Krücken (2003) finds that the discourse for university reforms is not met at the level of organisational practices and call for using path dependency in higher education to explain continuity of practices within universities. Other studies apply path dependency to explore specific aspects of higher education such as student representation (Chirikov and Gruzdev 2014), knowledge transfer to industries (Delfmann & Koster 2012) and policy formulation (Feeney and Hogan 2017).

I use path dependency as the conceptual framework to examine the decisions and activities of the new INIs and determine the influence of location on their development path. Instead of examining the effect of location on the various aspects of their development, I examine the cascading effect of location in their subsequent development in a path-dependent manner through the following questions. First, I analyse if the placement of the new INIs in their respective locations can act as a contingent event. Second, I identify the initial conditions of the INIs arising due to their placement in their respective locations. Third, I analyse if and how these initial conditions can set off a series of sequential or self-reinforcing events for the new INIs that are hard to undo.

Research design

I chose a research design that allowed me to focus on identifying and tracing back the key decision arenas of the new INIs pertaining to their three main functions—teaching, research, and outreach. I selected a qualitative design with multiple cases that is suited where contextual conditions are relevant to the phenomenon under study or the boundaries are not clear between the phenomenon and context (Yin 2017). It has gained acceptance in many studies where universities in their entirety are analysed, such as this one. In such studies, including four to ten case studies allows for exploring differences between case studies and replicating the findings from one case across cases and provides a good basis for generalisation (Eisenhardt 1989).

I used three criteria to shortlist the INIs to be approached for participation. The first criterion was the age of the INIs. Although the initial period of new universities depends on the people involved and the dynamic interplay of external environments with internal resources and challenges, most scholars have suggested this to be around 10 to 15 years (Perkin 1969; Clark 2003). Thus, I longlisted 63 INIs that were established between 1996 and 2008 and, thus, were aged between 8 and 20 years by the time of this study. The second criterion was the disciplinary focus of the INIs. I further shortlisted the INIs in four disciplines—architecture and planning, management, science and technology—since institutions in these disciplines are likely to be entrepreneurial, include a broad range of teaching and research activities, and engage with their external stakeholders (Clark 1998). The third criterion was to include the INIs to represent the various types of region (i.e. urban, semi-urban, and rural) that they were situated so as to gather evidence from cross-regional and multi-site fieldwork. This allowed for data triangulation by collecting data from different contexts and ensured the validity and reliability of the findings (Pinheiro et al. 2012; Peck 2003; Hudson 2003). Based on the above criteria, I found 26 INIs to be eligible for inclusion in this study. I sent requests for participation to the Directors—the Heads of the INIs—of these INIs, of which seven INIs agreed to participate. I refer to them as HEIs in the remainder of this article. Each HEI represented a unique combination age, disciplinary focus and location (see Table 1).

Data collection and method of analysis

I collected the required data from three sources. First, a total of 185 faculty members were approached to opt-in to participate in a semi-structured interview, of which 73 agreed to participate (Fig. 1). Given the higher likelihood of senior faculty members to participate in institute development and external engagement activities (Demb and Wade 2012; Glass et al. 2011), I approached only those faculty members with Associate Professor or above appointments and/or, held a senior administrative role (see Figs. 1 and 2).Footnote 1 I developed and followed an interview schedule to uncover the sequence of events in the HEIs and the condition and decisions proceeding and preceding the same. I asked questions to understand the alternative options that were considered in their development path and the rationale for choosing one over another.

Second, I obtained the vision or mission documents, annual plans and reports of the HEIs either from their websites or by writing to their concerned authorities. Third, in order to understand the macro-environment related to the expansion of INIs, I obtained the following documents from publicly available sources corresponding to the overall expansion of the HE system in India during the same period: government legislations and planning documents for higher education in India, official documents pertaining to the expansion of INIs, and media articles and opinion pieces.

I used descriptive coding technique to identify the major decision arenas of the HEIs since their establishment. In the second cycle coding, I adopted axial coding that described the properties and dimensions these major decision arenas, such as the people involved in these decisions, their motivations and dilemmas faced for taking such decisions, and the institutional rationale and logic of such decisions. I analysed the aspects of contingency and sequential or self-reinforcing events, i.e. how each decision or event of the HEIs was linked to the subsequent one.

The placement of the HEIs as a contingent event

The first decision that I analysed was about the location of the HEIs. The reports of various government committees on revamping higher education in India had no mention about deciding the location of the new INIs. I could not find any analysis or conceptual framework in the literature that could explain the location of the HEIs. Besides, none of the documents pertaining to the HEIs had any detail about the process or criteria used to decide their location. The parliamentary debates indicated that the location of the HEIs was subjected to political negotiations. One of MPs commented as below:

After bifurcation of Bihar [one of the states in India that was divided in to two states: Bihar and Jharkhand], almost all institutes of excellent education and research went into Jharkhand. Establishment of IISER in Bihar will be a step towards minimisation of prevailing regional imbalance in the distribution of educational institutes across the country. (Parliamentary Debate, MP, 27 November 2006)

A member of the Committee set up for expanding the IITs also emphasised that the final decision about the location was based on “both the quality of the college and the political push and pull”. Having an institution of the cadre of an INI in their constituency gave the opportunity to the MPs to showcase it as their contribution to the location, as is reflected in the narrative of the Foundation Stone laying ceremony of one of the IITs:

The Union Minister of State of External Affairs emphasised the efforts put by him and other leaders in sanctioning of the IIT. He also expressed hope that the IIT will open up opportunities for receiving quality technical education in the state.

These were reinforced by the interview participants of the HEIs, as is seen in the following comments: “Influential persons [from this location] in 1990s wanted that it should not go elsewhere. They persuaded the state, central government” (P 43, IIM-SO); “In the beginning, there was a proposal to have four IISERs. Then the state government came in an added one more [in this location]” (P 20, IISER-SN).

The above comments indicate that the decision about the location of the HEIs was not based on the higher education context or deliberations around the appropriateness of the location to host the HEIs. Instead, it was a consequence of the political negotiation between the government and the representative MPs of the states. Such negotiations are likely to depend on the relationship between the ruling party in the states and the centre and the potential for the politicians and political parties to leverage the HEI for patronage and prestige (Lall and House, 2005). Thus, the decision about the location of the HEIs was random and exogenous to the context of the HEI. It was a contingent occurrence in the sense it could not be explained based on theoretical conditions or what was already known about the HEIs.

Consequently, many of the new INIs were situated in rural or semi-urban regions, which varied in their appropriateness to host a new INI. The (urban) region of IIT-UN had a vibrant technology industry making it suitable for the HEI to forge industry collaborations. Similarly, the establishment of IISER-SN coincided with a regional development plan to establish several national-level HEIs that quickly turned the region into an educational hub. However, the other HEIs did not have any such inherent locational advantage. Such heterogeneity in the higher education environment of the region in which the HEIs were situated further accentuated the uncertain local conditions that they found themselves in.

Initial conditions due to contingent placements of the HEIs

The initial contingent event in path dependency may not be a single well-defined decision or event but can be a set of conditions that act as an impetus to stimulate further action. I discuss below three initial events or conditions of the HEIs that arose due to their contingent placements in their respective locations. These initial conditions are distinguishable from the subsequent events or actions and cannot be considered causal determinants (Sydow et al. 2009). However, the contingent placement of the HEIs and these initial conditions imply that if the HEIs were located in a different location, their current state would not have been reached, and thus, resulting in lasting and unique effects of the location on their future paths (Garud et al. 2010).

The first condition was the uncertain operational situations that the HEIs found themselves in. The HEIs were planned on campuses with nearly hundred acres of land, which was difficult for the state to find within the main city locations. Thus, the land allocated to the HEIs was in peri-urban locations with poor connectivity to the main city. IIT-SN and SPA-SN went through a troublesome period to obtain a legally hassle-free land. All the HEIs experienced significant delays in construction of the campuses; of the seven HEIs in the study, only IIM-SO had completed its campus construction. In responding to criticism for such delays, the government cited various reasons including delay in handing over land by the states, preparation of master plans and appointment of architects. As a result, the initial funding allocated to the HEIs was revised to meet cost escalation and unplanned expenditures.

Such uncertainty was further exacerbated due to the lack of preparedness of the local stakeholders (e.g. state government officials, and urban and local bodies) to host an institution of the cadre of INI. Many interview participants indicated that since the local stakeholders were not consulted before deciding the location, the HEIs had to negotiate with them for the required operational resources and support. The comments below describe the contrasting experiences of two HEIs with their local stakeholders:

As far as State Government is concerned IIT is a very big deal. They really look up to IIT and bend over backwards to help us. The only thing they cannot do is give us money. (P 67, IIT-RN)

Being a national institute, [state] ministry people were not giving any weightage to us. When you have a Director of the institute who is not answerable to the state government, it becomes a problem. …It was always a friendly relationship; whenever we invited them [the state government officials], they came. (P 53, SPA-SN)

Hence, the HEIs faced several procedural hurdles in starting their operations, as described in the following comments: “There have been continuous requests going [to the local stakeholders for support] but these were out of control otherwise we would have taken much pace” (P32, IIT-SN); “The new institute, the new campus if you see, we are struggling with everything right now. There were debates on land, now there is no water supply; there is no electricity, for everything there is negotiation with the government and localities” (P7, IIM-SN). These experiences indicate that the location and surrounding region were caught off guard about hosting the HEIs, and their preparedness and willingness to support establishing them differed significantly.

The second event was the hiring of the initial group of faculty members in the HEIs. Several factors related to the location of the HEIs, such as proximity to parents, opportunities for spouses to work, education for kids and other lifestyle-related preferences, and the state of campus development were the main considerations for the faculty members to join the HEIs in the initial years. The Director of IIT-RN described the situation as “On an average, one or two faculty members leave us every year due to lack of work opportunities for their spouses”. Thus, the location of the HEIs was instrumental for the initial group of faculty members to join the HEIs. The initial group of faculty members was subsequently instrumental in shaping the future paths of the HEIs through various ways including hiring of subsequent faculty members and shaping various institutional developmental aspects. Such people involved during the initial period can set the HEIs on a course to either academic excellence and international competitiveness or to mediocrity and oblivion (Morozov and Shchedrovitskiy 2018).

The third event was the involvement of the “Mentor Institute”—one of the established INIs that was assigned by the government to mentor the HEIs and to help them start their operations at the earliest. It was chosen to be an INI that was closely located to the HEIs to ensure convenience of commuting. However, their role went beyond just operational assistance to the HEIs. The faculty members from the Mentor Institutes helped in the development of the new HEIs in several ways including designing policies, teaching, and advising in campus development. In some cases, a faculty member from the Mentor Institute was appointed as an interim Director until a full-time permanent Director was appointed. Emphasising the significance of the Mentor Institute, one of the participants mentioned: “I think that’s been a struggle so to come out of the shadow of the established IIMs”. In this way, the Mentor Institutes were involved in deciding which ideas and practices of the established INIs need to be adopted by the HEIs and also trained the HEIs on adapting these ideas.

The above described initial conditions were characterised by the archetypical practices and policies that the HEIs had to comply with for being set up as INI, funded by the government. For instance: all the INIs in a given discipline admitted students through a common admission criterion; the number of students to admit and faculty to be recruited were approved by the government; and the recruitment of faculty and staff members had to comply to standardised norms at the national level. I discuss below how these aspects, along with the initial conditions, determined the decision arenas and their significance for the development of the HEIs.

Reactive sequences for path development

Reactive sequences are temporally ordered and causally connected events, where each event in the path is both a reaction to antecedent events and a cause for subsequent events (Sydow et al. 2009). The connection between two sets of events is established due to the lack of alternatives and constraints in moving forward in any other direction. I analyse below how the location and the resultant initial conditions set off reactive sequential events for the HEIs to move them on an emergent path.

Balancing teaching and research: teaching first, research later

One of the main objectives of the government to establish the HEIs was to expand access to quality higher education offered by the established INIs. The emphasis on teaching and academic programmes was seen at multiple levels of the HEIs. At the macro-level, commitment to teaching was often the first one on the mission statements of the HEIs. This was reflected in the mission statement of SPA-SN: “committed to produce best Architects and Planners of the Nation to take up the challenges of physical and socio- environmental development of global standards”. IISER-SN was the first of its kind INI focussing on undergraduate teaching in sciences. Several of its faculty members mentioned that “education” precedes “research” in the name of the institution to reflect its focus on teaching. Education underpinning the rationale of establishing the new IITs was reflected in the speech by the Prime Minister of India (Prime Minister’s Office, 2008):

This [the intake capacity constraint] is highly regrettable because it denies opportunity to thousands of deserving young men and women. … such talent must not go un-utilised. Many more such institutes are needed. Realising this, our government decided to increase the capacity by creating eight new IITs in the 11th Five Year Plan” (Para. 3).

At a normative level, many academics believe that teaching, rather than research, is their primary commitment (Hattie and Marsh 1996). The relationship between teaching and research activities are also shaped by the management of available resources at the institutional level (Coate et al. 2001). The teaching activities in the HEIs were managed and monitored through collective efforts of the faculty members and institutional arrangements such as the academic council. However, research activities were managed by individual faculty members, with the HEIs being a facilitator to support and monitor the same and promote a culture of research excellence. The faculty members were encouraged to search for research grants and collaborators on their own. Hence, they considered teaching and research as distinct and competing goals.

Notwithstanding the above, almost all the faculty members interviewed were involved in institutional development efforts of the HEIs in the initial years. However, the HEIs were required to adhere to standardised prescribed norms of evaluating faculty performance that was applicable to the INIs. These norms gave far more importance to the research and teaching activities for performance evaluations and promotions. Hence, several faculty members regretted in getting too involved in such activities, as reflected in the following comment:

Yes 100 percent, there is a loss of research. … I know for sure, there are lots of people who also came from abroad would say looking at the facility I don’t want to come here. This will take away five years of my life doing nothing, or I would struggle. ..So they decided not to come back. For those who can face this problem, five full years have gone by, nothing has happened. (P 45, IIT-UN)

Such conflict faced by the faculty members to balance their administrative, research and teaching functions are represented by “the requirements of curricula versus scholarly interests of the faculty, the focus of graduate versus undergraduate programs, the disciplinary versus institutional identity of the faculty, and the publicly declared versus the actual operating functions of universities” (Hattie and Marsh 1996, p. 508). Although the research and teaching functions in universities can be complementary, the potential conflicts in time, energy and commitment faced by faculty members can lead to negative relationships between research and teaching functions (Serow 2000). Hence, faculty members in the HEIs treated administration, research and teaching as distinct activities that were managed, assessed and funded separately.

The conflict between teaching and research was further accentuated by the government’s requirement of the HEIs to begin their academic sessions within a year of their establishment. Although the HEIs started their academic sessions in a year in their temporary campus, their subsequent activities were characterised with constraints such as inadequate campus infrastructure in temporary campuses, delays in construction of permanent campus and reliance on visiting or guest faculty members from the Mentor Institute. Under such circumstances, the HEIs continued to prioritise teaching over research, as reflected in the following comment:

It takes five to six years to get established and by that time you need to also get your own infrastructure in place. When you have both in place - the classes are running and infrastructure is in place - probably then you will think of doing research. I think this comes naturally also, initially teaching, putting the class in order, getting faculty, starting our own courses, getting our own executive programmes then the research excellence comes. (P 46, IIM-SO)

The analysis indicates that the location and the initial conditioned mentioned earlier influenced the infrastructure and faculty available in the years leading to starting of academic programmes first and research later.

Developing teaching paths

The HEIs begun their operations in a temporary campus in the same location—typically another government-owned facility—until their permanent campus was constructed. The size, location and quality of infrastructure of their temporary campus were key considerations for the HEIs to decide the nature and scale of programmes that could be started in the initial years. Faculty members at the IIM-SN and IIM-SO indicated that they could have offered more management development programmes if the permanent campus was completed. Due to space constraints in the temporary campus, IIT-SN, IIT-UN and IISER-SN began their academic sessions with programmes that needed less laboratory space. One of the participants at IIT-SN described:

We started with Computer Science and Electrical Engineering as the kind of infrastructure that is required for these are not very heavy... We didn’t want to start with Civil, Mechanical and Metallurgy, all of these required very heavy labs. … So, once we established that we thought now we can expand to other disciplines. (P32, IIT-SN)

Besides the above, the initial set of programmes and courses was also influenced by the interests of the faculty members recruited in the initial years and those available from the Mentor Institutes to teach in the HEIs. In many cases, the HEIs considered the pedagogical practices of the Mentor Institutes as a starting point or benchmark to design their own teaching practices.

The HEIs considered offering niche programmes only after a group of faculty members joined in a given field of study. Once the faculty members joined and infrastructure was completed, the HEIs considered developing programmes to suit local demands and expectations, which helped them gain local support and engage with the surrounding region. For instance, the IIM-SN developed customised programmes for the government sector available in the location whereas the IITs had developed part-time programmes for the locals.

Developing research paths

The initial conditions above also impacted the sequencing of research activities in the HEIs. The funding by the government was restricted to establish the infrastructure needed for teaching and the students, with only a limited portion available to the faculty members for their research. As a result, the faculty members had to compete for resources—not only amongst themselves but also with the teaching and administrative priorities of the HEIs—to be able to progress their research. Many of them recounted their struggle in the initial years to establish their research laboratories due to limited space and funding, impacting the nature of research projects taken up. A faculty member described how having external funding in the initial years helped him overcome the infrastructural limitations.

I have been fortunate in funding that before I joined the Institute, the director of my previous institute was very keen to continue the collaboration through a bilateral partner research programme. It has been a very significant source of third-party funding. We didn’t have any basic facilities. The primary contribution came from the institute, but it is supplemented about 50% or 75% through third-party funding. (P18, IISER-SN)

Due to the uncertain operational conditions, the faculty members whose research did not rely on laboratory infrastructure could start their research projects sooner than those whose research involved experimental work. Such faculty members had to operate in makeshift arrangements, or they initiated new research projects with less infrastructure requirements. Similarly, faculty members who could get external funding through grants could establish their laboratory sooner.

Likewise, without much institutional resources for research and the uncertain operational conditions, the faculty members in the initial years preferred to continue collaborations with their pre-existing colleagues, instead of starting new projects. Thus, not just the research activities but also the nature of research projects that were started were also shaped by the uncertain operational conditions in the and the faculty recruited initial years.

Outreach and regional engagement in development paths

Conducting outreach activities for the local community did not emerge as a major decision arena from the analysis. One of the participants mentioned, “none of these IIMs have anything to do with the local city or the local place, and the state”. Many participants who were engaged in such activities described them as an individual pursuit to give back to the society, as seen in the following statements: “It is just individual. At the moment, I think no other IIT or at least I can guarantee my IIT or new IITs there is no such cell that promotes collaboration between the institute and region” and “This is a drive [referring to outreach activities] which is coming from inside”.

Sans the outreach activities, the HEIs faced several challenges to engage with the region in a mutually beneficial manner in the initial years, as reflected in the following comment: “I think we needed to have some kind of evangelist for each of these SIGs [an initiative to engage with the region]”. However, once the research and teaching agendas were established in a given area, the HEIs were able to combine both to develop a comprehensive agenda to engage with the region. Describing his approach towards setting one such entity, one of faculty members expressed the need to bring together multiple colleagues together, as below:

So when we got the infrastructure, then it was like, when we have the expertise why not have the Centre of Excellence. …Then we pumped up and consolidated. Now that the centre is available, we are providing the industrial consultancy and industrial problem solving. (P 35, IIT-SN)

Regional engagement activities are not structured as mutually exclusive to either teaching or research (Uyarra 2010; Weerts and Sandmann 2010). They require faculty members to go beyond their individual disciplinary research and teaching activities. Hence, the sequencing of teaching and research activities of the HEIs made it challenging for the HEIs to initiate regional engagement in the initial years. Thus, such initiatives were feasible once a critical mass of faculty members had joined and were willing to explore broad thematic areas of research, which followed from the preceding research and teaching activities of the HEIs.

The development paths of the HEIs

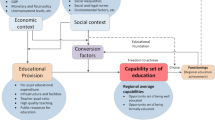

The analysis shows that the placement of the HEIs in their respective locations to be a contingent event that can make the development of HEIs path dependent. The HEIs developed through a set of reactive sequences that followed from this contingent event. The first decision for the HEIs was that of their location followed by appointment of the Director and the Mentor Institute. This was followed by an emphasis on constructing their permanent campus. Faculty recruitment followed, being significantly influenced by the earlier steps. The faculty members, the location and the availability of the infrastructure in the initial years added up to shape the sequence of the initial academic programmes launched. This was followed by initiating research activities by the HEIs that required external funding and were dependent on the state of the infrastructure and the support from the local stakeholders. Outreach and regional engagement activities were initially restricted to individual faculty members, aligned with their research and teaching interests. However, once a threshold number of faculty were hired, academic programmes and research projects were started and campus construction was completed, the HEIs could initiate efforts to institutionalise regional engagement. I have depicted the development paths of the HEIs in Fig. 3.

The findings discussed are limited to single disciplinary new universities and hard to generalise to new universities with multiple disciplines. While the nature of development paths of the HEIs was common across the disciplines, there were also variations, as per their discipline, in their pace of development and their specific trajectory of development. The HEIs in the science and technology disciplines had larger infrastructural and funding needs than the HEIs in other disciplines. Thus, their location and temporary campus in the initial years are likely to be more significant to start academic programmes first and research later. Similarly, due to the applied nature of their disciplines, the IITs and the SPAs were more engaged with the region for fresh research ideas and developing pilot research projects compared with the IISERs which focussed on theory development and experimental studies. These aspects need to be fully explored to bring out disciplinary differences in the development path of the HEIs.

Discussions

The findings discussed above indicate that various conditions, such as the nature of initial funding, autonomy of the universities, and the infrastructure and support available at the local level, can influence this path. The government set the overall vision for the HEIs to expand high-quality education in India. It provided them significant funding, status and autonomy—yielding significant authority over the HEIs in the initial years through means such as appointment of the Director, allocation of land, release of funding and sanctioning of faculty numbers. The HEIs thus focussed on education programmes and infrastructure development first to respond to the authority but subsequently developed their research areas and regional engagement. However, as new universities grow, their development will be characterised by their reputation, identity and competitiveness instead of being opportunistic, indeterminant and evolutionary. This opens up discussions about various other factors or conditions that need to be considered to fully understand the development of new universities.

The HEIs in this study would be subjected to institutional forces—coercion, cognitive or normative—to adopt archetypical practices and ideas from the established INIs. These can push the HEIs on to a development path characterised by their identity that will be determined their belongingness to the INIs and their anticipated role in the national HE system as an INI. In such cases, their local context will play an important role in deciding the level of discretion that they can apply in adopting and modifying dominant practices and ideas. The HEIs on such development paths will need to balance the pressures to mimic their established counterparts, and gain legitimacy, with their need to differentiate and form a unique identity (Huishman et al., 2002; Brennan et al. 2018). Further analysis is needed to examine the different levers available to the HEIs, such as the autonomy to deviate from taken-for-granted norms and practices, the diversity of the funding base that they have built, and their relationships with the local stakeholders, to resist such institutional forces and avoid being in a path they can trap them in conformity.

A related processual question in the Indian context is how did existing ideas from the established INIs circulate to the HEIs? Most of the faculty members of the HEIs were young, for whom working at the HEI was their first academic appointment. As a result, the Director of the HEIs, along with their Mentor Institute, is likely to have a significant influence in deciding which ideas are legitimate and steer the HEIs on to an alternative development path. However, they would need organisational capacity and support at the local level to put these ideas into practice (Stensaker and Benner 2013). Therefore, further analysis is needed about the role of the Director and the governance norms of the HEIs (e.g. collegium, bureaucracy, corporation and enterprise). Such an analysis would need to go beyond the experiences of the senior faculty members and examine the motivations and goals of the young faculty members who are likely to put existing ideas to practice, and are also more likely to introduce new and innovative ideas (Coate et al. 2001; Weerts & Sandmann 2010).

The HEIs perceived the other INIs as competitors for attracting faculty and students, and for acquiring resources. Such competitiveness can move them on to an alternate development path, where they can find themselves in the same reputation race as that of the established INIs. Such a development path would depend on their globally referenced quality of research and their research productivity, the image of their surrounding region and the availability of potential resources and networks locally or elsewhere. These can help the HEIs offset the reputation lag from their established counterparts that they experienced in the initial years (Glass et al. 2011). Hence, further analysis is needed to examine the motivations of students and young faculty members to select the HEIs, the constraints faced by faculty for their research projects, and the role of location in shaping graduate attributes and job market outcomes of students.

The network positioning of the HEIs at the local, national and global levels can also shape their development paths. The HEIs were established within the pre-existing network of the INIs. In such cases, the alignment between their national and global aspirations with the local expectations and demands will influence their embeddedness and positioning in the local network (Brennan et al. 2004). This alignment will be determined by their organisational strategy and capacity, and the proactiveness of their leadership to engage with the local leaders, and the challenges and motivations of the HEIs to institutionalise such engagement (Pinheiro et al. 2012). Analysing the above would need evidence from the local stakeholders about their openness, motivations and challenges to engage with the HEIs.

The above conditions or factors indicated above will shape the identity, competitiveness and network positioning of the HEIs. These can move the HEIs on to an alternate developmental path that will either make their development agnostic of their location or reinforce the effect of location leading to a situation of lock-in.

Notes

The non-teaching staff in Indian universities typically assume administrative roles and do not participate in decision-making activities. Likewise, for many of the young faculty members of the HEIs, it was their first academic appointment, and thus, they were not likely to participate in decision-making and institutional development activities. Hence, both were excluded in this study.

References

Brennan, J., Cochrane, A., Lebeau, Y., & Williams, R. (2018). The University in its Place: social and cultural perspectives on the regional role of universities. Springer.

Brennan, J., King, R., & Lebeau, Y. (2004). The role of universities in the transformation of societies: an international research project.

Chirikov, I., & Gruzdev, I. (2014). Back in the USSR: path dependence effects in student representation in Russia. Studies in Higher Education, 39(3), 455–469.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: organizational pathways of transformation. Issues in higher education. Elsevier Science Regional Sales, 665 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10010 (paperback: ISBN-0-08-0433545; hardcover: ISBN-0-08-0433421, $27).

Clark, B. R. (2003). Sustaining change in universities: continuities in case studies and concepts. Tertiary Education and Management, 9(2), 99–116.

Coate, K., Barnett, R., & Williams, G. (2001). Relationships between teaching and research in higher education in England. Higher Education Quarterly, 55(2), 158–174.

Delfmann, H., & Koster, S. (2012). Knowledge transfer between SMEs and higher education institutions: differences between universities and colleges of higher education in the Netherlands. Industry and Higher Education, 26(1), 31–42.

Demb, A., & Wade, A. (2012). Reality check: faculty involvement in outreach & engagement. The Journal of Higher Education, 83(3), 337–366.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Feeney, S., & Hogan, J. (2017). A path dependence approach to understanding educational policy harmonisation: the qualifications framework in the European higher education area. Higher Education Policy, 30(3), 279–298.

Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 760–774.

Glass, C. R., Doberneck, D. M., & Schweitzer, J. H. (2011). Unpacking faculty engagement: the types of activities faculty members report as publicly engaged scholarship during promotion and tenure. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 15(1), 7–30.

Goddard, J., & Puukka, J. (2008). The engagement of higher education institutions in regional development: an overview of the opportunities and challenges. Higher education management and policy, 20(2), 11–41.

Harris, M., & Holley, K. (2016). Universities as anchor institutions: economic and social potential for urban development. In Higher education: handbook of theory and research (pp. 393–439). Springer, Cham.

Hattie, J., & Marsh, H. W. (1996). The relationship between research and teaching: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 507–542.

Hudson, R. (2003). Fuzzy concepts and sloppy thinking: reflections on recent developments in critical regional studies. Regional Studies, 37(6–7), 741–746.

Huisman, J., Norgård, J. D., Rasmussen, J. R. G., & Stensaker, B. R. (2002). ‘Alternative’ universities revisited: a study of the distinctiveness of universities established in the spirit of 1968. Tertiary Education & Management, 8(4), 315–332.

Krücken, G. (2003). Learning the ‘new, new thing’: on the role of path dependency in university structures. Higher Education, 46(3), 315–339.

Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society, 29(4), 507–548.

Marginson, S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72(4), 413–434.

Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437.

Mezias, S. J., & Glynn, M. A. (1993). The three faces of corporate renewal: institution, revolution, and evolution. Strategic Management Journal, 14(2), 77–101.

Morozov, A., & Shchedrovitskiy, P. (2018). Establishing a world-class university from scratch: an initiator’s perspective. In Accelerated Universities (pp. 174-192). Brill Sense.

P.G. Altbach, L. Reisberg, J. Salmi, and I. Froumin. Accelerated universities: ideas and money combine to build academic excellence. Global Perspectives on Higher Education. Brill Academic Publishing, 2018. ISBN 9789004366091.

Peck, J. (2003). Fuzzy old world: a response to Markusen. Regional Studies, 37(6–7), 729–740.

Perkin, H. J. (1969). New universities in the United Kingdom. Case studies on innovation in higher education.

Pinheiro, R., Benneworth, P., & Jones, G. A. (Eds.). (2012). Universities and regional development: a critical assessment of tensions and contradictions. Routledge.

Serow, R. C. (2000). Research and teaching at a research university. Higher Education, 40(4), 449–463.

Stensaker, B., & Benner, M. (2013). Doomed to be entrepreneurial: institutional transformation or institutional lock-ins of ‘new’ universities? Minerva, 51(4), 399–416.

Stensaker, B., Välimaa, J., & Sarrico, C. (Eds.). (2012). Managing reform in universities: the dynamics of culture, identity and organisational change. Springer.

Sydow, J., Schreyögg, G., & Koch, J. (2009). Organizational path dependence: opening the black box. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 689–709.

Uyarra, E. (2010). Conceptualizing the regional roles of universities, implications and contradictions. European Planning Studies, 18(8), 1227–1246.

Weerts, D. J. (2014). State funding and the engaged university: understanding community engagement and state appropriations for higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 38(1), 133–169.

Weerts, D. J., & Sandmann, L. R. (2010). Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(6), 632–657.

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: design and methods. Sage publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Misra, D. A path-dependent analysis of the effect of location on the development of new universities. High Educ 80, 289–304 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00480-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00480-7