Abstract

The system of academic promotion provides a mechanism for the achievements of staff to be recognised. However, it can be a mechanism that creates or reflects inequalities, with certain groups rising to the top more readily than others. In many universities, especially in the global North, white men are preponderant in senior academic ranks. This leads to concerns about sexism and racism operating within processes of promotion. There is a global sensitivity that academic hierarchies should be demographically representative. In this study, we examine the data on eleven years of promotions at the University of Cape Town (UCT), a highly ranked, research-led university in South Africa. Its historical roots lie in a colonial past, and despite substantial increases in the number of black scholars, its academic staff complement is still majority white, driving the intensification of its transformation efforts. A quantitative analysis using time to promotion as a proxy for fairness was used to examine patterns of promotion at the university. Although international staff, those in more junior positions, with higher qualifications and in certain faculties enjoyed quicker promotion time, no association was found between time to promotion and gender. There were some differences in time to promotion associated with self-declared ethnicity (taken as synonymous with race), but these associations were not consistent. Although our findings provide some quantitative evidence of UCT’s success at creating a fair system of academic advancement, broader demographic transformation remains a priority. However, this cannot be addressed in isolation from the wider higher education enterprise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is a paradox in studies of academic promotion. On the one hand, there are concerns about unrepresentative demography mostly demonstrating that minorities are not proportionately represented in senior positions, and on the other hand, many quantitative studies show the absence of bias. It is for this reason that there continues to be research on why the demographic profile does not change or changes unevenly or only slowly.

Academic promotion is the process which facilitates upward staff mobility within the institutional hierarchy. Ad hominem promotion refers to a process where individual staff members apply for personal promotion, usually in response to institutional calls for applications and is distinct from applying for vacant posts which are open to external applicants. Staff apply for promotion to achieve recognition, status and increased remuneration. Since staff vest their identities heavily in work, promotion is often a focus of their ambition. For the process to be credible, it needs to be fair and free from any suspicion that it is biased, at the individual and at the group level.

Ideally, a system should be both fair to individual applicants and reflect equitable success for all groups in the staff complement. For decades, there has been global concern expressed about demographic representation. For example, men continue to dominate senior positions or minority groups are not reflected adequately in staff composition. There are, thus, two ways of approaching questions of promotion—one focussing on the individual and the other on groups. In this article, we reflect on trends in promotion at the University of Cape Town (UCT), by presenting findings of an analysis of eleven years of promotions data from a research-intensive university in South Africa. The national higher education context features a strong emphasis on transformation, a short-hand for the need to address inequalities that were associated with apartheid.

At UCT, issues of promotion and, particularly, the composition of the professoriate have been in the spotlight for many years. In the main administrative building, an artwork by Svea Josephy dating from 2004 pronounces that “88.5% of Full Professors at UCT are White Males”. Yet, the stakes have been raised in the more recent period by protest actions. This study was conducted against the backdrop of turbulence in the higher education system in South Africa. In 2015, the Rhodes Must Fall movement began at UCT when a student activist, Chumani Maxwele, threw excrement over a statue of the imperialist mining magnate, Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902). The objection of protesters was to the “colonial nature” of UCT and the demand was for “decolonization” (Hodes 2017; Nyamnjoh 2016; Jansen 2017). This was soon followed by the Fees Must Fall movement, a student-led movement calling for free higher education. Both movements had substantial country-wide support though lost much of this when they rapidly became violent.

At UCT, the protests provided space for some staff to express unhappiness about the promotion process which they alleged was biased in terms of race and gender. While, in general, staff (particularly those whose promotion applications had failed) were not convinced of the fairness of the process, there was now a more general suspicion that “black” staff were being prejudiced. The analysis reported here was undertaken partly in response to these concerns.

University academic promotions—global issues

Concerns about academic promotions are not new. In 1973, David A Katz wrote in the American Economic Review, “Recently, there has been considerable concern regarding the problems associated with evaluating and rewarding university professors. While these problems have always existed, they have been compounded by the recent economic recession and the growth of political activism which transcends the traditional line between student and teacher.” (Katz 1973, 469). One of his conclusions was that “an uneven distribution of rewards appears to be inequitable” (Katz 1973, 476). Katz drew attention to issues of unevenness in rules and processes and to the extensive and often unfettered power of senior administrators. Similarly, a study on job satisfaction in the US amongst academic staff found “Employees want fairness in promotions and a promotion system whose criteria are clear” (Locke et al. 1983: 345).

Attempts to reform promotion systems to ensure fairness and equity have been made over the last half century, as reviewed in the subsequent texts. However, in the last two decades, such initiatives have taken place in a context of globalization and marketization of higher education and the introduction of new managerialism that has swept across the world and into universities (Altbach 2004). This context impacts on promotions in two distinct but contradictory ways. In the first instance, new approaches to governance in higher education have given increasing power to managers. Their work is central to the new audit and evaluation culture taking hold in universities. As promotion requirements have become more explicit and the promotion application process more demanding, the ability of managers to influence the process has been reduced. In this sense, the global trend has been towards transparency and, therefore, towards administrative fairness. However, with greater specificity around the duties and the processes of academic work, the ability of academics to exercise discretion, however well-justified, has been reduced and they increasingly become bureaucrats who simply implement rules. Thus, the nature of academic work has been changing and many have argued that the new managerialism threatens the very nature of the university (Connell 2013). There is now less space for discussion, and academic autonomy has been reduced while non-academic managers have decision-making powers historically exercised collectively by academics (Davies 2003). In this context, the issue of promotion may seem less important than keeping one’s job, having control over who and what one teaches and enjoying the autonomy and collegiality that has often been an important consideration in university employment. Changes to the promotion system under the guise of promoting fairness may in fact benefit a particular group of staff—“the more research-active or managerially-inclined staff” and “provide new avenues for rapid promotion” (Shore 2008: 291–92). On the other hand, new management regimes permit greater top-down initiatives which can include addressing demographic staffing inequalities. New managerialism often embraces the language of equality, yet it operates autocratically. Demographic equality can, thus, be advanced to the detriment of institutional culture. For example, “‘hard’ managerialism is seen to be incompatible with concerns about equity and feminist values” (Deem 1998: 66).

Studies on promotion—fairness, inequality and doing something about it

Are particular groups of staff affected by a glass ceiling which puts a cap on their promotion? A number of studies have examined the position of women academics with the consensus being that in some cases they are seemingly affected but that when decision-making is open and a systematic procedure is used, decisions that foster the glass ceiling phenomenon may be averted.

“When procedures for promotion decisions are standardized and criteria for decisions are well established, qualified women may fare at least as well as qualified men. When procedures are not standardized, or when criteria for promotion decisions are unspecified or vague, there may be more occasion for gender-related biases favoring men to affect the outcomes of the promotion process.” (Powell and Butterfield 1994: 82)

Studies on promotion have often focussed on the performance of women. Such studies disclose a complex picture, revealing in some cases that women receive more promotions than men (Hersch and Viscus 1996), others revealing only “fairly minor racial and gender differences in promotion rates” (Lewis 1986: 417) and others noting male advantage but one that has been declining (Baldwin 1996: 1184). Nevertheless, the under-representation of women and staff of colour in senior positions at universities is an ongoing global concern (Allen et al. 2000; van den Brink and Benschop 2012; Oforiwaa and Afful-Broni 2014; Winchester et al. 2006).

In seeking to understand inequalities in the academic hierarchy and specifically why some groups are less successful than others, attention is often paid to the procedures and criteria by which promotions are decided. The suspicion is that discrimination against minority groups may occur because the criteria favour some groups or that the processes by which the criteria are applied are biased.

A critique of promotion criteria often focusses on the undue weight given to research achievement (often held to advantage men) rather than teaching, perhaps because research output can be more easily measured. As students increasingly are viewed as customers to be wooed and pleased (as well as taught and supported), some universities are placing greater emphasis on teaching in the assessment of promotability (Subbaye and Vithal 2017). The same goes for engaged scholarship and social responsiveness with increasing recognition being given to the conversion of research into public good where the focus is not so much on knowledge creation but on knowledge application and “academic citizenship” (Macfarlane 2007; McMillan 2011).

Nevertheless, inequality in staff hierarchies remains common and questions continue to be asked about the promotion processes. While this is a logical place to search for explanations, studies do not readily endorse this as an explanation for inequality. In a comprehensive study of Australian universities where academia has felt the influence of feminism for many decades, for example, a group of researchers conducted a study to explain why only 16% of Australian professors were female (whereas they constituted 39% of the academic labour force), they adopted a hypothesis which states that “under-representation of women in academia reflects barriers in the promotion process” (Winchester et al. 2006: 506). They further proposed that policies that “do not take career interruption into account or which focus primarily on research as a criterion for promotion would disadvantage women. Such policies would in effect constitute barriers to their promotion” (Winchester et al. 2006: 506). They concluded, however, that “the under-representation of women at senior levels cannot be attributed to flaws and barriers in the promotions process” (Winchester et al. 2006: 518). More broadly, they found that “the lack of women in senior positions was not due to discrimination or bias” (Winchester et al. 2006: 519).

Building capacity that strengthens the chances of, particularly minority, staff to get promoted, is common. Mentoring is frequently used to support staff on the road to professorship (Gardiner et al. 2007). Integrated approaches can be successful. In the Chemistry Department at the University of Berkeley, California, where minorities and women are performatively on par with white males at the PhD level (when, historically, white men have been dominant), a bundle of initiatives was introduced. A “culture of structure”—where “the community’s knowledge, implementation and even application of standards” create “a culture in which students know what they need to do, and advisers know what they should encourage”—succeeded in advancing staff and equity (Mendoza-Denton et al. 2018: 301). Interventions make a difference, but they seldom eradicate inequality. Limitations are put down to problematic assumptions that are mobilized in interventions (for example, that certain groups of staff are inherently less competent), poor implementation or to broader structural factors that resist transformation (Johnson-Bailey and Cervero 2008; Ibarra et al. 2010; Iverson 2007).

Demographic inequality may be a result not of biased promotion process but of recruitment processes and staff retention. This point is tellingly made in a big study of the US military which sought to understand the shortage of senior female officers. The conclusion is that the under-representation is a result of high female turnover and overly selective recruitment strategies (Baldwin 1996). Baldwin argues that the focus of affirmative action should be on retention and recruitment (rather than promotion) if a more representative officer profile was regarded as important.

National context and the transformation debate

South Africa’s universities are creatures of colonialism and, subsequently, apartheid. After 1948, the state used universities to produce ideological support for “separate development” and placed white, National-party supporting, males in positions of authority, often as Vice-Chancellors at the Afrikaans language universities and those established to cater separately for black students.

With the dawn of democracy in South Africa, universities became sites of policy debate on how they should be transformed in order to serve and reflect post-apartheid conditions. Affirmative action was one of the key mechanisms debated to redress racial (and gender) inequalities at universities. Some effect was given to the idea of redistribution in the Higher Education Act of 1997 which expressed a vision for a “transformed, democratic, non-racial and non-sexist system of higher education” which would emphasize “equity of access” and “fair chances of success” and “eradicate discrimination” (Motala and Pampallis 2001: 23).

The transformation of universities involved many elements, including student access, pass rates, acquisition of higher degrees and curriculum, but also included the composition of academic staff. Government addressed the issue of staff demographics in its 1997 Education White Paper. It sought to improve the “proportion of blacks and women on academic and executive staff of institutions” (Cloete and Bunting 2000: 75). While not explicitly identifying targets, the implication was that there should be alignment between national demography and staffing complements. In the area of redress and access, for example, it stated “While the number of Africans has increased substantially, the level is still smaller than the proportion of Africans in the population” (RSA 1997: 28). A lack of alignment was observed in the gendered distribution of posts. Women occupied between 30 and 35% of academic positions, but 90% of “the senior and middle ranks” were male (Cloete and Bunting 2000: 35–6).

Initially, the pace of change was slow. From 1993 to 1998, the proportion of white academic staff only went down from 87 to 80% with Cloete and Bunting concluding that, “the higher education system is moving much more slowly than was expected in the White paper. At this pace the higher education system will struggle to satisfy the requirements of the Employment Equity Bill” (Cloete and Bunting 2000: 36). The Gender Equity Task Team supported these conclusions but also identified mechanisms which it believed explained the under-representation of women on university staffing complements, including sexist university cultures that discriminated in numerous ways against women. The Task Team recommended that Universities “scrutinise and then standardise promotion criteria” and that account should be taken of “factors which militate against women gaining promotion” (Wolpe et al. 1997: 158).

Government pressure on universities to “transform” has increased. In 1998, the Employment Equity Act imposed obligations on employers (including universities) to advance the interests and positions of employees and potential employees who were black, female or disabled (Portnoi 2003). Although the focus of the Act was on ensuring the appointment of people from “designated groups”—black, female and disabled—the Act also stated that “the designated employer must provide training and skills development for affirmative action appointees to obtain the necessary skills or qualifications required for a position in the particular workplace” (Portnoi 2003: 79).

A raft of government interventions and organic institutional responses has had significant effect. From 1998 to 2011, the number of university students in South Africa nearly doubled (to 937,455) and the student racial demography changed dramatically with the percentage of black students rising from 55 to 80%. In gender terms, the shift was also dramatic with the proportion of female students rising from 45 to 58% (RSA 2013: 28). On the other hand, government noted limitations including that while “there are almost equal numbers of men and women (staff) overall, women are clustered in the lower ranks of the academic hierarchy” (RSA 2013: 28). Despite the initial slow increase in black African staff numbers, government became increasingly concerned with the status of black African staff, a sub-category of the generic “black” staff which had initially informed transformation policy. The proportion of black African staff rose to 30% by 2012 (from 12% in 1998) (RSA 2013: 28). The black African percentage of the national population was 80.48% according to the 2011 Census (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_South_Africa). More recent data from the Department of Higher Education and Training shows that by 2017 this percentage had risen further to 38%, reflecting an almost three-fold increase in numbers of black African academic staff, rising from 2817 in 2000 to 7500 in 2017 (an average annual increase of 5.9% per year since 2000 relative to a 0.9% decrease per year for white academics). Staff classified as white comprised 47% of academic staff in 2017 compared to 70% in 2000 (Higher Education Data Analyser www.heda.co.za/PowerHEDA/dashboard.aspx accessed 04 August 2018).

Nation-wide dissatisfaction with the slow pace of social and economic change in South Africa exploded onto university campuses in 2015. While indeed, “every university in South Africa is part of and complicit with some form of unacceptable behaviour supported by tradition, culture and politics whether tacit or spelt out, whether conscious or unconscious” (Lange 2014: 9), we shall argue that the detail of current university practices cannot be reduced simply to a reflex of the past, as though history locks universities into replicating their origins.

UCT—the promotions system and how it works

In the next section, we turn to the analysis of eleven years (2005–2015) of UCT’s promotions data. UCT has seven faculties, each with its own promotion criteria. These are clearly set out, and although not uniform, there are consistency checks in place, and they each have a similar structure which blends four elements—research; teaching and supervision; administration, management and leadership; and social responsiveness/engaged scholarship (community-orientated activity). Each faculty has a process that starts with an annual call for applications for promotion and leads through various stages to a consideration of an application by a large committee that is chaired by the Dean of that faculty and includes the deputy Vice Chancellor, two outside Deans, and other members as determined by the Faculty board. Promotion applications are generally submitted via a consultative process with Heads of Department which sifts out those unlikely to succeed. Although exact figures are not available, most applications are therefore successful.

Considering itself a research-led university, UCT has historically emphasized the importance of research and publication, priding itself on its rank as the highest ranked university in Africa (www.uct.ac.za, accessed 14 May 2018). UCT has a “Research Office” which is charged with promoting and supporting research to increase research productivity and make the university globally competitive. In this process, the Research Office recognises the close connection between research productivity and the promotion prospects of individual staff members (Masango 2015). In 2001, UCT established the Emerging Researchers Programme (ERP) in part as a response to the National Plan for Higher Education “to produce good, sustained research and to make South Africa ‘a significant player on the global stage’” (De Gruchy and Holness 2007: 2). Its aim was to concentrate on “young and/or inexperienced faculty members” with the aim of supporting “researchers in the development of their personal research profiles” (De Gruchy and Holness 2007: 2). This programme grew steadily, promoting interdisciplinary research (Breier and Holness 2011) and expanding its reach into the continent (Holness 2015). Its success was evident in the funding the programme received and in the enthusiastic involvement of UCT academic staff in its activities as well as to their upward mobility in the university’s hierarchy.

Government requirements for demographic transformation added to internal calls for equity. In 2006, UCT implemented an Employment Equity Policy. Its policy stated the following: “Using the University’s recruitment policy and procedures as a framework, every reasonable effort will be made to appoint suitable internal and external candidates from the designated groups to vacant positions” (UCT 2006: #7).

These formal commitments did make a difference but not of the dramatic nature hoped for or increasingly demanded by some staff and students. This led to suggestions of insincerity and of institutional racism. The widespread impression that UCT was resisting pressure to “transform” was echoed in commentaries where a “key problem” was named as “the obdurately white and male character of the academic staff in the sector” (Soudien 2008: 667). The situation was certainly not unique to UCT with academic sociologists in South Africa arguing that many black respondents believed that “certain institutions [were] still grappling with issues of transformation and that racism [was] experienced as a form of institutional racism” (Rabe and Rugunanan 2012: 562).

Methods

The project had two questions: The first was to determine the time it took to obtain an ad hominem promotion (hereafter referred to simply as promotion) at UCT. The second was to determine any factors that affected that time to promotion. Time to promotion was defined as the interval between the appointment or previous promotion of a staff member before 2005 and their first promotion between years 2005 and 2015. To avoid any bias, our analysis focussed on the time to the first promotion for all 471 academics promoted between 2005 and 2015 and did not consider any subsequent promotions during this period.

The dataset used for our analyses was provided by UCT’s Institutional Planning Department. Since these records are confidential, permission was first obtained from the Vice-Chancellor’s Office and, thereafter, ethics approval was obtained from the Faculty of Humanities Ethics Committee. The dataset was anonymised to ensure confidentiality. The dataset contains promotion records of all the academic staff members that served at the University of Cape Town (UCT) between the years 2005 and 2015. Universities are required to report demographic data to the government, and for this purpose, staff are required to declare their race (often used interchangeably with ethnicity in HR documents). For government purposes, to promote racial redress, reporting of self-declared ethnicity is required using for the most part, old apartheid categories which are as follows: black African (“African”), “Coloured” (mixed race), “Indian”, “White” and “Other”. Some staff choose to define themselves as “not declared”. For official reporting purposes, these staff are categorised as “white”. The issue of racial belonging is sensitive and politically charged. Acknowledging this, we nevertheless have accepted these categories as given and use the generic term “black” to refer to all staff not classified as “white”.

A second (denominator) dataset contained details of 2080 academics employed at UCT in the study period. Over 25% (that is, 528) staff served at UCT for at least ten years within that period, 323 served between seven and nine years, 467 served between four and six years and the remaining 762 were at UCT for less than four years between 2005 and 2015.

As a preliminary assessment of the promotion system at UCT, the null hypothesis tested whether the time to first promotion is similar for UCT academic staff across various pre-defined demographic categories, namely age category, nationality, self-declared ethnicity, gender, disability, faculty, highest qualification and previous appointment (position, career track, permanent/contract and internal/external). Although part of the Faculty of Commerce, the Graduate School of Business is managed separately and was thus analysed separately. Age is calculated at baseline, that is, age at the time of assuming the occupied position prior to the year 2005. External appointments are those academics who were employed at other institutions prior to their occupying the UCT position from which they were promoted.

The skew data distribution observed precluded the application of parametric statistical tests. Survival analysis (Collett 2003) was also considered, but unfortunately, the denominator dataset available on all academics employed but not promoted during the analysis period did not include all the details required. Data transformation (e.g. logarithmic) was avoided to facilitate interpretation of the inferences. Consequently, non-parametric statistical analysis techniques, including the Kruskal–Wallis test (Kruskal and Wallis 1952) and quantile (or median) regression (Koenker and Hallock 2001; Koenker and Bassett 1978), were adopted. All analyses were executed using R statistical software (R Core Team 2018).

Results

Of the 539 promotions recorded between 2005 and 2015, 409 (87%) achieved one promotion, 56 staff members received two promotions and 6 received three promotions. For academics who received more than one promotion during the study period, only the time to their first promotion was analysed, as noted previously. This resulted in the analysis of 471 academics with at least one promotion in this period (Table 1). Their median time for promotion was 5.33 years, with a wide range from 9 months to 36 years.

Table 2 summarises the time to promotion for each of the pre-defined categories of the staff, and Table 3 reports quantile (or median) regression analysis of time to first promotion, after adjusting for the effect of the other variables (as some demographic characteristics may be unevenly distributed between groups). These analyses were performed for the full promotion dataset (all 471 academics receiving at least one promotion during the study period), as well as post-hoc sub-set analyses on the two largest groups of staff in a category of interest, namely (1) those that were promoted from lecturer to senior lecturer and (2) South African academics.

These analyses found no evidence of gender bias. Overall, the median time to promotion was 5 years (with an interquartile range, IQR, of 4 to 8 years) amongst male academics and 5.67 (IQR 3.5–8.5) years amongst female academics; this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.30). Nor were there any statistically significant differences inferred using Kruskal–Wallis tests with respect to disability or in non-permanent contracts, although the small numbers of academics promoted in these groups may have precluded meaningful statistical analysis of these variables. However, time to promotion was shown to be associated with the remaining factors in at least one of the datasets analysed (Table 3).

Age category

The median time to promotion by age category ranged between 3.00 and 7.29 years. In the full dataset, relative to those aged 25 to < 35 years (with a median time to promotion of 5.42 years), those in the 35–< 45 and 55–< 65 age categories had a significantly shorter time to promotion by medians of 1.83 and 4.23 years, respectively. Similar findings were observed amongst the South African academics subset but not in the Lecturer to Senior Lecturer cohort (Table 3).

Nationality and self-declared ethnicity

South Africans comprised the majority (76%) of academics promoted, and the proportion promoted (23%) was similar to that for the international academics (21%) (Table 1). However, in the full dataset, after adjusting for other variables, the 19 academics who declared their ethnicity as “Other” had a median time to promotion that was 1.6 years shorter than their 51 colleagues who declared their ethnicity as “African”; overall, there was no significant difference between times to promotion for those categorising themselves as “Africans”, “Whites”, “Coloureds” and “Indians”. In the subset analysis of lecturers, the 122 academics who declared their ethnicity as “White” had a median of time to promotion about 1.75 years quicker than their 29 colleagues who declared their ethnicity as “African”. Amongst the South African academics promoted, the 24 academics who declared their ethnicity as “Asian” had a quicker median time to promotion (by ~ 1.87 years) compared to their 24 colleagues who declared their ethnicity as “African” (Table 3).

Prior appointment

Median times to promotion were similar for academics with previous appointments at UCT (internal) and those who assumed their previous positions from other institutions (external). However, after adjusting for other factors, academics whose previous appointment or promotion was at UCT were promoted a median of 0.73 years (~ 9 months) earlier than those with non-UCT previous appointments (Table 3).

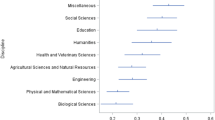

Faculty

There were some differences between faculties in their times to promotion, which was shortest overall in the Law Faculty with a median of 4.25 years, compared to 6 years in the Science Faculty and 6.25 years in the Centre for Higher Education and Development (identified as “Higher Education” in the Tables). After adjusting for other factors, academics were promoted a median of 2.9 years sooner in the Law Faculty and 2.3 years sooner in the Commerce Faculty than their colleagues in the Science Faculty. Shorter median times to promotion in the Law and Commerce faculties than the Science Faculty were also observed in both subset analyses. In the subset analysis of lecturers promoted to senior lecturer, the median time to promotion was also about 1 year shorter in the Humanities Faculty and the Centre for Higher Education and Development. In the subset analysis of South African academics, times to promotion were also almost 5 years sooner in the Graduate School of Business than in the Science Faculty (Table 3).

Academic rank

The overall median time to promotion by academic rank prior to promotion in the full dataset ranged from 3.92 years (research officer) to 6.54 years (senior lecturer). Relative to the median time to promotion for associate professors (of 6.5 years), significantly shorter times were inferred for clinical educators (by 4.5 years), lecturers and senior research officers (both by 2.96 years) and research officers (by 2.69 years). In the multivariate subset analysis of South African academics, the median times to promotion were similar between associate professors (6.58 years) and senior lecturers (7 years) and significantly shorter for all other academic ranks by a range from 2.37 to 4.49 years. Relative to those with only Bachelors or Honours degrees, academics with Masters and Doctoral degrees were promoted a median of 2 and 3 years quicker, respectively. Similar results were observed in both subset analyses (Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined whether UCT’s promotion system systemically discriminated against certain groups, particularly black and female staff. A quantitative analysis used time to promotion as a proxy for fairness. Our findings reveal that, in general, there was evenness across various categories with few systemic differences. Time to promotion between genders and between racial groups, showed no consistent, statistically significant differences in the three groups of staff analysed. However, international staff, those in more junior positions, with higher qualifications and in certain faculties enjoyed quicker promotion time.

The median times to promotion are appreciably shorter for non-South African than South African staff. A possible explanation is the recruitment policy which purposefully, as a reflection of the country’s labour laws, privileges South African candidates over non-South Africans. This may lead to less qualified South Africans (if deemed appointable) being selected over better qualified non-South Africans. As a result, where non-South Africans are appointed, they may have already advanced further along a career path which would translate into meeting promotion milestones earlier than their South African colleagues.

At the lecturer to senior lecturer level and amongst South African academics, “White” and “Asian” lecturers respectively were quicker to promotion than “African” colleagues, in these subset analyses. It is possible that this reflects a bias in the system in favour of “White” and “Asian” academics. However, as with the advantage of international academics, it could also reflect the affirmative action recruitment policy, which requires that if there are “White” and “African” appointable candidates, the “African” candidate should be appointed even if less experienced or less published. A possible result of this policy is that “African” staff may have further to go to meet promotions criteria to senior lecturer than “White” colleagues. Once this initial hurdle has been completed, there is no evidence at the more senior levels of racial differences in the progress rates of staff, although we did see in the full dataset that the 19 staff who declared their ethnicity as “Other” were promoted more rapidly than their “African” colleagues. Overall, in the full data set, there was no significant difference between times to promotion for “Africans”, “Whites”, “Coloureds” and “Indians”.

There is also no significant difference in time to promotion between men and women in any of the groups of staff analysed. This may reflect that any advantages of male academics are balanced by other factors. For example, more females qualify for university entrance and more female students graduate in South Africa despite equal numbers at the start of school; this was observed for all subgroups of race, age, socioeconomic status, province of origin and institution attended (Spaull and Van Broekhuizen 2017). Affordable access to child care in South Africa may also reduce the gender gap between academics.

As expected, those with higher qualifications and those in more junior positions were generally promoted more rapidly. The impact of age on promotions is not consistent. Those with previous appointments as UCT staff (“internal”) get promoted more quickly than those who come to UCT from other universities (“external”). UCT staff may know the game better and thus shape their work to effect the best and most efficient route to promotion—a form of local knowledge. The pace of promotions varied across faculties. Staff in the Law and Commerce faculties were decidedly quicker to promotion than those in Science. Despite university-wide efforts to provide uniformity and fairness, these differences possibly reflect different appointment and promotion criteria, such as more weight being given to professional (as opposed to research and teaching) performance.

Another possible explanation for different promotion rates between faculties lies in the different weights that their rules give for research achievements. In three faculties, scoring for research is tied closely to achievement in the National Research Foundation’s demanding peer-reviewed rating system that distinguishes between international leadership (A), international recognition (B) and establishment as an independent researcher (C). In 2013/14, only 11% of the country’s researchers (2959) were NRF-rated (NRF 2014: 3). Only 24% (714 out of 2959) rated researchers were A or B rated (international leaders or internationally recognised). An applicant for promotion wishing to score 7 or above for research in the Science Faculty would “usually (be) B-rated”. In Health Sciences, a similar score could be garnered by being “rated C1 or higher”, with a similar requirement in the Engineering and Built Environment Faculty. However, the four other faculties did not prescribe an NRF rating as a feature of a high promotion score though the Law Faculty indicated that an NRF rating would be understood to be a sign of research excellence (allowing for researchers with much lower NRF ratings or no rating at all, to claim a high research score). These differences might well contribute to different promotion outcomes of staff members with similar profiles and records of achievement in different faculties.

Overall, therefore, we find little quantitative evidence of any consistent pattern of promotion bias. It might be expected, at least in some quarters, that the country’s past, that featured prominent racial and gender inequalities and discrimination, would be mirrored in the university’s institutional processes with at least some residual effects 20 years after the dawn of democracy. Literature highlights situations in which promotions are likely to be unfair and what is required to promote fairness (see, for example, Luthans (1967), Katz (1973) and Powell and Butterfield (1994)). UCT, like many universities, has increasingly addressed sources of procedural bias by producing clearly defined criteria and processes for promotion which are approved both at the Faculty and Senate levels. The decision-making committees are fairly large, so power cannot be concentrated in the hands of a few. There are appeal mechanisms in place which provide a further safeguard. In this context, the indication that there is little systemic bias in UCT’s promotion system is confirmation that these interventions have worked.

This does not, however, mean that there is no cause for concern at UCT. Although the number of “African” professors at UCT has risen from 4 to 24 in the last 10 years and associate professors from 8 to 24, “African”, “Coloured” and “Indian” (i.e. black) professors still only constitute 21% of all professors and 28% of all associate professors. When it comes to issues of representation, it remains the case that the university’s professoriate (full and associate professors) is still largely “White” and male. For this reason, there is a need for future qualitative research to explore the experiences of the promotion process amongst academic staff, focussing on differences between faculties and disciplines, as well as on race, gender, age and country of origin.

UCT’s situation is not an unusual one, and there are no quick fixes. Paying attention to demographic transformation must be undertaken while at the same time confronting structural limitations and recognising broader challenges that ask questions about the place of universities in society (Enders 2001: 23–24). In South Africa, these questions have often, but not always, been subordinated to questions of demography, the distribution and occupation of academic posts by race and gender. Such an approach is mechanistic and can conceal other challenges (Lange 2014). An obvious structural limitation is the time that it takes for an academic to develop a record of achievement that warrants promotion. Another structural limitation is the existing pool of staff. If there are few women or black staff in the pipeline, it will be difficult in absolute terms to increase the numbers of senior academic staff and, thus, adjust the demographic, without the vast resources needed to recruit these staff from the relatively small pool of qualified suitable individuals that not only universities but government and business are also seeking to attract.

The existing pool of black and female academics is growing as a result of legislation and the commitment of universities themselves. In 2015, the Department of Higher Education and Training introduced a programme to increase the numbers of black junior staff in the country’s universities. The New Generation of Academics Programme (NGAP) has thus far introduced 373 young black staff into academic positions at South Africa’s 26 public universities (www.ssauf.dhet.gov.za/ngap.html). In addition, UCT has been a pioneer of staff development initiatives in South Africa. One such recent initiative is the Next Generation Professoriate which is a mid-career academic staff development and support programme that has enrolled 45 black and/or female academics and constituted them as a cohort of future leaders at the university. In time, these initiatives will likely impact on the academic hierarchy, feeding black and female staff into the professoriate. However, this should not detract from the serious nature of the pipeline issue that originates in and is compounded by South Africa’s very poorly performing schooling system. Numerous studies come to the same conclusion: “South Africa has the worst education system of all middle-income countries that participate in cross-national assessments of educational achievement. What is more, we perform worse than many low-income African countries” (Spaull 2013: 3).

Attempts to accelerate demographic transformation at other institutions have included lowering the retirement age to force mostly white and male staff to leave earlier and thus release positions for up-and-coming black staff. Such an approach comes with dangers including losing highly productive academics and their institutional knowledge. UCT has not taken this approach. Where such measures are accompanied by aggressive, explicitly racialized managerialism, demographic transformation can be achieved at the cost of institutional culture and high levels of staff demoralization, as was the case at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Chetty and Merrett 2013).

Austerity, a current condition at South African universities caused by state underfunding of higher education, can result in “rationalisation”, leading to “low morale, fear and frustration” amongst staff (Portnoi 2003: 83). The drift to managerialism in universities makes possible interventions in appointments and promotion which undermine long-held values of academic meritocracy. Even though there is a countervailing force to ensure transparency with the proliferation of rules, there is a global struggle for what academics regard as the “academic soul” of universities (Anderson 2008; Shore and Taitz 2012). A further danger is that universities become pawns in a larger game of national politics. Jonathan Jansen’s grim prediction that South African universities are heading towards irrelevance as knowledge producers or places of public higher education is precisely predicated on the view that the state no longer values universities per se but sees them as motors and sites of transformation (Jansen 2017). In post-independence Africa, universities became places of patronage and training for bureaucrats, conceived as integral to national development but no longer places of knowledge production or research (Johnson 2012; Cloete and Maassen 2015).

Holding a balance between delivering on core academic functions and the pace of demographic transformation, which are only at tension when the pool of appointable applicants in “designated groups” is small remains at the forefront of higher education politics in South Africa. Seeking a more demographically representative staff body is pursued while also seeking to maintain standards of excellence. This is most often understood as maintaining standing in the global university rankings despite cautions about the weaknesses of this system including bias against global South institutions (Jöns and Hoyler 2013). A major effort has been made to increase the numbers of junior black and female staff, either by “growing your own timber” or by filling senior posts with junior incumbents, creating a pathway for future ascent up the academic hierarchy. These interventions take time before they ripple through the system, via successful promotion, into the higher echelons of the university.

Conclusion

The development of an unbiased promotion system is important to the legitimacy and mission of a university. At UCT, this goal has largely been achieved. At the same time, we have noted pressures on the university from within (staff and students) and without (government) to give more emphasis to transformation which has often been equated with addressing demographic inequality. We have argued that there is a need to continue to build a pipe-line of black and female staff, supporting their recruitment and their careers once they become staff members, but at the same time have warned that quick fixes are potentially dangerous. Further advance along the road of demographic transformation at UCT is assured but will take time.

References

Allen, W. R., Epps, E. G., Guillory, E. A., Suh, S. A., & Bonous-Hammarth, M. (2000). The black academic: faculty status among African Americans in U.S. higher education. Journal of Negro Education, 69(1/2), 112–127.

Altbach, P. G. (2004). Globalisation and the university: myths and realities in an unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management, 10(1), 3–25.

Anderson, G. (2008). Mapping academic resistance in the managerial university. Organization, 15(2), 251–270.

Baldwin, J. N. (1996). Female promotions in male-dominant organizations: the case of the United States military. The Journal of Politics, 58(4), 1184–1197.

Breier, M., & Holness, L. (2011). Towards a theorisation of a cross-disciplinary research development programme at the University of Cape Town. Acta Academica Supplementum, 2, 149–168.

Chetty, N., & Merrett, C. (2013). The struggle for the soul of a South African University: The university of KwaZulu-Natal. Academic freedom, corporatisation and transformation. Pietermaritzburg: Self Published.

Cloete, N., & Bunting, I. (2000). Higher education transformation. In Assessing performance in South Africa. Cape Town: Centre for Higher Education Transformation (CHET).

Cloete, N., & Maassen, P. (2015). Roles of universities and the African context. In N. Cloete, P. Maassen, & T. Bailey (Eds.), Knowledge production and contradictory functions in African higher education (pp. 1–17). Cape Town: CHET.

Collett, D. (2003). Modelling survival data in medical research (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall.

Connell, R. (2013). The neoliberal cascade and education: an essay on the market agenda and its consequences. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 99–112.

Davies, B. (2003). Death to critique and dissent? The policies and practices of new managerialism and of ‘evidence-based practice’. Gender and Education, 15(1), 91–103.

De Gruchy, J. W., & Holness, L. (2007). The emerging researcher: nurturing passion, developing skills, producing output. Cape Town: UCT Press.

Deem, R. (1998). ‘New managerialism’ and higher education: the management of performances and cultures in universities in the United Kingdom. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 8(1), 47–70.

Enders, J. (2001). A chair system in transition: appointments, promotions, and gate-keeping in German higher education. Higher Education, 41, 3–25.

Gardiner, M., Tiggemann, M., Kearns, H., & Marshall, K. (2007). Show me the money! An empirical analysis of mentoring outcomes for women in academia. Higher Education Research & Development, 26(4), 425–442.

Hersch, J., & Viscus, W. K. (1996). Gender differences in promotions and wages. Industrial Relations, 35(4), 461–472.

Hodes, R. (2017). Questioning ‘fees must fall’. African Affairs, 116(462), 140–150.

Holness, L. (2015). Growing the next generation of researchers. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press.

Ibarra, H., Carter, N.M., & Silva, C. (2010). Why men still get more promotions than women. Your high-potential females need more than just well-meaning mentors. Harvard Business Review, 80–85.

Iverson, S. V. (2007). Camouflaging power and privilege: a critical race analysis of university diversity policies. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43(5), 586–611.

Jansen, J. (2017). As by fire—the end of the South African university. Cape Town: Tafelberg.

Johnson, R. W. (2012). The African university—the critical case of South Africa and the tragedy at the UKZN. Cape Town: Tafelberg.

Johnson-Bailey, J., & Cervero, R. M. (2008). Different worlds and divergent paths: academic careers defined by race and gender. Harvard Educational Review, 78(2), 311–332.

Jöns, H., & Hoyler, M. (2013). Global geographies of higher education: the perspective of world. Geoforum, 43, 45–59.

Katz, D. A. (1973). Faculty salaries, promotions, and productivity at a large university. The American Economic Review, 63(3), 469–477.

Koenker, R., & Bassett, G. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 33–50.

Koenker, R., & Hallock, K. F. (2001). Quantile regression. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 143–156.

Kruskal, W. H., & Wallis, W. A. (1952). Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 47(260), 583–621.

Lange, L. (2014). Rethinking transformation and its knowledge(s): the case of South African higher education. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning (CRISTAL), 2(1), 1–24.

Lewis, G. B. (1986). Gender and promotions: promotion chances of white men and women in federal white-collar employment. The Journal of Human Resources, 21(3), 406–419.

Locke, E. A., Fitzpatrick, W., & White, F. M. (1983). Job satisfaction and role clarity among university and college faculty. The Review of Higher Education, 6(4), 343–365.

Luthans, F. (1967). Faculty promotions: an analysis of central administrative control. The Academy of Management Journal, 10(4), 385–394.

Macfarlane, B. (2007). Defining and rewarding academic citizenship: the implications for university promotions policy. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 29(3), 261–273.

Masango, C. A. (2015). Combating inhibitors of quality research outputs at the University of Cape Town. The Journal of Research Administration, 46(1), 11–24.

McMillan, J. (2011). What happens when the university meets the community? Service learning, boundary work and boundary workers. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(5), 553–564.

Mendoza-Denton, R., Patt, C., & Richards, M. (2018). Go beyond bias training. Nature, 557, 299–301.

Motala, E., & Pampallis, J. (2001). Educational law and policy in post-apartheid South Africa. In E. Motala & J. Pampallis (Eds.), Education and equity: the impact of state policies on South African education (pp. 14–31). Johannesburg: Heinemann Publishers.

National Research Foundation (NRF). (2014). Evaluation and rating: facts and figures 2014. Pretoria: National Research Foundation.

Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2016). Rhodes must fall: nibbling at resilient colonialism in South Africa. Bamenda: Langaa Research and Publishing.

Oforiwaa, O. A., & Afful-Broni, A. (2014). Gender and promotions in higher education: a case study of the University of Education, Winneba, Ghana. International Journal of Education Learning and Development, 2(1), 34–47.

Portnoi, L. M. (2003). Implications of the Employment Equity Act for the higher education sector. South African Journal of Higher Education, 17(2), 79–85.

Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (1994). Investigating the ‘glass ceiling’ phenomenon: an empirical study of actual promotions to top management. The Academy of Management Journal, 37(1), 68–86.

R Core Team. (2018). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/.

Rabe, M., & Rugunanan, P. (2012). Exploring gender and race amongst female sociologists exiting academia in South Africa. Gender and Education, 24(5), 553–566.

Republic of South Africa (RSA) (1997). A programme for the transformation of higher education. (Education White Paper 3) Pretoria: Department of Higher Education.

Republic of South Africa (RSA) (2013). White paper for post-school education and training. In Building an expanded, effective and integrated post-school system. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education.

Shore, C. (2008). Audit culture and illiberal governance. Universities and the politics of accountability. Anthropological Theory, 8(3), 278–298.

Shore, C., & Taitz, M. (2012). Who ‘owns’ the university? Institutional autonomy and academic freedom in an age of knowledge capitalism. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 10(2), 201–219.

Soudien, C. (2008). The intersection of race and class in the South African university: student experiences. South African Journal of Higher Education, 22(3), 662–678.

Spaull, N. (2013). South Africa’s education crisis: the quality of education in South Africa 1994–2011. Johannesburg: Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE).

Spaull, N., & Van Broekhuizen, H. (2017). The 'Martha effect': the compounding female advantage in South African higher education. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series, 14.

Subbaye, R., & Vithal, R. (2017). Teaching criteria that matter in university academic promotions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(1), 37–60.

University of Cape Town. (2006). Employment equity policy as approved by council, December 2006. University of Cape Town.

Van den Brink, M., & Benschop, Y. (2012). Slaying the seven-headed dragon: the quest for gender change in academia. Gender, Work and Organization, 19(1), 71–92.

Winchester, H., Lorenzo, S., Browning, L., & Chesterman, C. (2006). Academic women's promotions in Australian universities. Employee Relations, 28(6), 505–522.

Wolpe, A., Quinlan, O., & Martinez, L. (1997). Gender equity in education. Pretoria: Department of Education.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jane Hendry, Michelle Jacobs and Vimal Ranchhod for their contributions to this study.

Funding

The support of the National Research Foundation (NRF) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadiq, H., Barnes, K.I., Price, M. et al. Academic promotions at a South African university: questions of bias, politics and transformation. High Educ 78, 423–442 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0350-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0350-2