Abstract

While organizations strive for ethical conduct, the activity of negotiating offers strong temptations to employ unethical tactics and secure benefits for one’s own party. In four experiments, we examined the role of constituency communication in terms of their attitudes towards (un)ethical and competitive conduct on negotiators’ willingness and actual use of unethical tactics. We find that the mere presence of a constituency already increased representatives’ willingness to engage in unethical behavior (Experiment 1). More specifically, a constituency communicating liberal (vs. strict) attitudes toward unethical conduct helps negotiators to justify transgressions and morally disengage from their behavior, resulting in an increased use of unethical negotiation tactics (Experiment 2–3). Moreover, constituents’ endorsement of competitive strategies sufficed to increase moral disengagement and unethical behavior of representative negotiators in a similar fashion (Experiment 4ab). Our results caution organizational practice against advocating explicit unethical and even competitive tactics by constituents: it eases negotiators’ moral dilemma towards unethical conduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ethicality and ethical conduct are important values of modern organizations (Ardichvili et al. 2009; Spiller 2000) and a growing body of research is dedicated to investigate antecedents of unethical conduct (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). Particularly important for studying (un)ethical business conduct are negotiations, the most consequential forms of interactions within and between organizations (De Dreu and Gelfand 2007), in which organizations task employees such as managers to represent their interests. In negotiations, both parties are simultaneously motivated to compete (i.e., secure own interests) and cooperate, because they can only achieve their goals together with the other party (Walton and McKersie 1965). This mixed-motive dynamic provides ample opportunities for ethical transgressions and negotiators constantly face the dilemma between upholding ethical values versus securing their direct constituents’ performance interest (cf. Kaufman 2002). This latter temptation is additionally fueled by a fear of losing one’s position in the negotiation (Dees and Cramton 1991; Lewicki and Stark 1996). Indeed, the use of unethical tactics is not uncommon among negotiators (Bazerman 2011; Olekalns et al. 2014).

We investigate an important, yet hitherto overlooked antecedent of unethical negotiation choices, that is, how the presence and communication of constituencies shape negotiators’ unethical choice. In representative negotiations multiple stakeholders are involved on both sides. Representatives have a boundary role conflict where they need to both attend to the other parties’ needs and actions, and to the preferences of the constituency, who hold them accountable for their negotiation behavior and the outcome (Druckman 1977). Importantly, these constituents do not have an active role at the negotiation table. This differentiates them from, for example, team negotiations, where different team members can play active roles during the negotiation process which requires coordination but also increases the potential of information-processing and a larger diversity of negotiation skills (Thompson et al. 1996; Hüffmeier et al. 2019). Pursuing the wishes of the constituency often requests a competitive approach (Druckman et al. 1972; Druckman 1977; De Dreu et al. 2014). In five studies, we investigate how the presence of a constituency and their attitude towards ethical, unethical, and competitive tactics affect negotiator’s unethical choices through increased moral disengagement. We follow prior work and conceptualize unethical choice as the combination of intentions and behavior (Borkowski and Ugras 1998; Martin and Cullen 2006). This is based on the model of Rest (1986), stating that the intention to behave unethically precedes unethical behavior and can be substituted for behavior. Especially for (un)ethical actions, intentions and behavior are positively associated (Detert et al. 2008; Volkema et al. 2004). Moreover, recent meta-analytic evidence has shown that correlations between antecedents and behavior are stronger than those between antecedents and intentions, suggesting that intentions are a good, yet possibly conservative, proxy for measuring behavior (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). We consequently study both intentions (Experiments 1, 2, 4ab) as well as behavior (Experiment 3).

We make three contributions to the literature on ethical decision-making. First, while much research has investigated cooperative and competitive norm endorsement from constituency members and representatives’ responses to such endorsement in their behavior (Aaldering and De Dreu 2012; Aaldering and Ten Velden 2018; Steinel et al. 2009), we move beyond the influence constituencies have on concession making. Instead, we found that constituents also influence unethical negotiation choices of representative negotiators—both indirectly, merely by being present, and directly, by communicating their attitudes towards (un)ethical behavior (Experiments 1–4). If representatives are willing to use unethical tactics when these are implicitly or explicitly approved by their constituency members, it is important to find out why. While competitive behavior is indeed likely to ensure individual gain, and can therefore be interpreted as good for the whole group, this is not necessarily the case for unethical behavior (Fleck et al. 2016). Moreover, the risk of employing unethical rather than competitive tactics is much higher; unethical behavior can result in sanctions if one is ‘caught’ displaying such tactics and there are psychological costs of dishonesty in terms of self-image (Mazar et al. 2008; Thielmann and Hilbig 2018, 2019). Second, we determine the process underlying representatives’ unethical behavior: Representatives whose constituents had liberal attitudes towards unethical tactics experienced moral disengagement; i.e. they felt freed from ethical responsibility and licensed to engage in unethical behavior due to the perception that the constituency allowed such unethical behavior (Experiment 4ab). Third and more broadly, our research contributes to intra-organizational coordination and behavior by warning against the potential downsides of endorsing competitive behavior (Experiment 4ab). Despite being acceptable and common in negotiations, we will show that constituents’ endorsement of competitive behavior suffices to increase unethical negotiation choices of representatives. In sum, our findings show that constituents should not only avoid showing liberal attitudes toward unethical behavior, but also be very careful when encouraging negotiators to behave competitively.

1.1 Unethical Negotiation Tactics

Negotiation research suggests that unethical negotiation tactics lie on a continuum of acceptability, ranging from clearly unethical (e.g., making false promises, lying about factual information) to barely ethical (e.g., pretending to be in no hurry to reach an agreement and hence not to concede soon). The latter examples have been categorized as ‘traditional competitive bargaining’ (Robinson et al. 2000). Based on previous findings (Cohen et al. 2014; Fleck et al. 2016; Lewicki et al. 2015), we define unethical negotiation tactics as separate from competitive but ethically acceptable ones. We conceptualize making false promises, misrepresenting information, attacking the network of the opponent and gathering inappropriate information about the opponent as unethical tactics. However, we exclude standard competitive tactics, which are widely perceived as appropriate in negotiations (Fleck et al. 2016). These include making unrealistically high opening offers, showing a strong resistance to concession making or falsely suggesting a lack of urgency to reach an agreement (see Cohen 2010; Cohen et al. 2014; Lewicki and Robinson 1998; Lewicki et al. 2015). This resonates with the conceptual and empirical distinction previously made between ethically appropriate and inappropriate negotiation tactics (Fleck et al. 2016). Importantly, competitive and unethical tactics are not only distinguishable, but also fundamentally different in normative acceptability. Negotiating competitively is aligned with general expectations of negotiations (e.g., the “fixed-pie bias,” Bazerman et al. 2000; Pinkley et al. 1995), and forms the default assumption in most negotiations, hence requires only a relatively small endorsement by the constituency (cf. Steinel et al. 2009). Unethical negotiation behavior, however, violates widely shared norms and may conflict with concrete rules of the organization. In contrast to competitive tactics, it is therefore normative to not use unethical tactics (see Fleck et al. 2016).

Despite the norm against unethical behavior, many negotiators deploy unethical tactics, and often benefit from doing so (Bazerman 2011; Olekalns and Smith 2007; Olekalns et al. 2014; Schweitzer et al. 2005). For example, withholding or misrepresenting information can yield an information advantage and opens the possibility of gaining information from the negotiation counterpart without revealing much yourself (Lewicki et al. 2015). In fact, some deceptive tactics, like bluffing and making false promises, are perceived as successful negotiation behavior, leading to higher personal or organizational profit and may thus be tempting for negotiators (Aquino 1998; Crampton and Dees 1993; Schweitzer and Croson 1999).

1.2 Representative Negotiations and Moral Disengagement

In many organizational or business negotiations, negotiators are not merely negotiating for themselves, but instead act on behalf of the organization, thereby representing a potentially diverse group of constituents (Steinel et al. 2009). We argue that the degree of unethical choices by negotiators is affected by the presence of and specific communication from constituency members about their attitude towards unethical negotiation behavior.

Negotiators who feel accountable to a group take a more competitive approach towards their counterpart than negotiators who do not represent a group (Benton and Druckman 1973; Mosterd and Rutte 2000; see also De Dreu et al. 2014). Such competitive behavior can be explained because representatives expect their constituencies to prefer a competitive approach, and subsequently justify their own behavior as being in the interests of their constituency. A competitive orientation toward the other party should protect and further the interests of the own group (Wildschut and Insko 2007; De Dreu et al. 2014). The presence of a constituency could similarly serve as implicit cue for representatives to make more unethical choices, given that such unethical tactics contribute to securing high outcomes. Thus, representatives could again justify their behavior with their responsibility of benefiting their constituency. Additionally, the mere presence of a constituency suggests not only that the representative is responsible for serving their interests, but also that there are multiple individuals morally responsible for the actual negotiation behavior that is employed in the name of the group. Together we predict that this may already suffice to nudge representatives towards unethical conduct in negotiation:

Hypothesis 1

Negotiators with a constituency are more willing to engage in unethical behavior than negotiators without a constituency.

Different from unethical behavior, competitive behavior is common practice in negotiation and widely accepted in business to secure high economic gains (Hüffmeier et al. 2014; Steinel et al. 2009). Thus, representatives may need an additional justification for employing unethical tactics. Such justification could come in two related ways.

Firstly, the present constituency members could directly communicate a liberal attitude towards unethical values. Representatives could interpret this as suggested behavior to secure high negotiation gains and directly follow this suggestion. Secondly, such explicit communication could activate a cognitive process of moral disengagement. The perception that ethical boundaries may be crossed for ‘the greater good’ (in this case, to serve the constituency) can help representatives to cognitively free themselves from responsibility for unethical behavior to the constituency and see themselves as mere agent of the constituents’ wishes. The message from the constituency thus steers them away from their moral compass and compensates for the psychological costs of acting dishonestly. This should in turn increase the probability of giving in to the temptation of using presumably beneficial but unethical behavior in negotiation. Justifying ones’ immoral actions and shifting responsibility of one’s own immoral behavior to other present actors with authority over the decision are captured in the psychological concept of moral disengagement. Experiencing moral disengagement is indeed associated with unethical behaviors, including unethical decision making in lab scenarios (Detert et al. 2008), self-reported unethical behavior (cheating, lying and stealing), unethical work behavior (Cohen et al. 2014; Moore et al. 2012) and even the use of unethical negotiation tactics (Tasa and Bell 2017). Put differently, moral disengagement can provide justification to serve the constituents’ wishes when they communicate liberal attitudes towards unethical tactics.

Based on this reasoning, we predict:

Hypothesis 2

Representatives whose constituency communicates a liberal attitude toward unethical rather than ethical values make more unethical negotiation choices.

Hypothesis 3

Moral disengagement mediates the effect of constituency communication on the willingness to and actual use of unethical negotiation tactics.

Explaining how and why representatives respond to their constituencies’ communication of their attitudes towards unethical tactics is an important first step in understanding the dynamics of representatives’ unethical behavior. However, often such communication may remain rather implicit. Competitive negotiation tactics, in contrast, are widely accepted as leading to higher individual profit (Hüffmeier et al. 2014; Siegel and Fouraker 1960) and form the expected default for representatives in absence of clear constituency norms (Benton and Druckman 1973; Mosterd and Rutte 2000).

Indeed, when at least a few constituents communicate a preference for competitive tactics, representatives are less likely to make concessions. Conversely, it requires a clear majority of the constituency to communicate a preference for a cooperative approach to induce more conciliatory tactics, including concession making and integrating priorities by representatives (Aaldering and De Dreu 2012; Aaldering and Ten Velden 2018; Steinel et al. 2009). In sum, constituencies’ endorsement of competition disproportionally affects representatives’ competitive value-claiming behavior (Steinel et al. 2009).

We argue that increased endorsement and willingness to employ competitive tactics can instigate not only more competitive, but also more unethical behavior by representatives. Ethical transgressions follow a “slippery slope” that starts with small transgressions (Welsh et al. 2015). While competitive and unethical tactics are conceptually distinct (see e.g. Cohen et al. 2014; Fleck et al. 2016), there is some indication that a competitive mindset can also promote unethical behavior (Schweitzer et al. 2005), suggesting that competitive negotiation tactics are at the top of this slippery slope. If true, competitive endorsement could already trigger moral disengagement and the associated justification to cross ethical boundaries ‘for the sake of the constituency’. Thus, we argue that competitive endorsement from the constituency suffices to initiate the process of moral disengagement that leads to unethical choice in negotiation:

Hypothesis 4a

A competitive constituency increases negotiators’ unethical choice as compared to a constituency endorsing ethical conduct.

Hypothesis 4b

The effect of Hypothesis 4a is mediated through moral disengagement.

We tested our predictions in a series of four controlled laboratory experiments. Experiment 1 tests whether the mere presence of a constituency can increase representatives’ willingness to use unethical tactics (Hypothesis 1). Experiment 2 investigates representatives’ willingness to use deception as a function of constituencies’ communication of different attitudes with regard to unethical values. Experiment 3 again tests Hypothesis 2 while measuring the actual use of unethical tactics during a negotiation. Experiments 4a and 4b test moral disengagement as the process underlying the increased use of unethical behavior as well as compares how the endorsement of competitive negotiation tactics “spills-over” and affects representatives’ use of unethical tactics (Hypothesis 3–4).

2 Experiment 1

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Sample and Design

Participants (N = 173, 50.3% female, 48.6% male, 1.2% ‘other’, Mean age = 30.84 years, SD = 11.64) were recruited via the online platform Prolific Academic in exchange for 0.67 GBP and were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions with or without constituency. According to G*Power, assuming a small effect size of d = .6 to reach a power of 1 − ß = .08 the required sample size was 148. We slightly oversampled to be able to potentially exclude participants that failed the attention check, which was however not necessary.

2.1.2 Procedure, Negotiation Task and Manipulation of Constituency

Upon indicating informed consent, participants were asked to imagine being part of one of three project teams, all invited by a company to design a new advertising campaign. A week before they would pitch their idea, they found out that one of the other invited teams had the same idea about the campaign. They would engage in negotiations with the other team and try to convince them to change their idea. Participants were explicitly told that their team had worked on preparing the campaign for 2 weeks, and that no collaboration with the other team would be possible should their team get hired. This information was allegedly not available to the other project team, and hence a way to deceive the other team during the negotiation. In the representative condition, participants were told that they represented a team, whereas participants were told that they negotiated for themselves in the individual condition. After these instructions we assessed the dependent variables and demographics.

2.1.3 Measures

Willingness to engage in unethical behavior was measured with 9 items from the SINS scale, consisting of the subscales ‘False Promises’, ‘Misrepresentation’, ‘Inappropriate Information Gathering’ and ‘Attacking Opponent’s Network’ nine (Robinson et al. 2000), Cronbach’s alpha = .88.

Moral disengagement was measured with the six-item measure by Shu et al. (2011, Cronbach’s α = .82). The items were adjusted to refer explicitly to the upcoming negotiation (e.g., ‘when thinking about the negotiation with the other party, I feel that rules should be flexible enough to be adapted in different situations, such as this negotiation’, Cronbach’s α = .79).

A manipulation check consisted of five items (1 = completely disagree; 7 = completely agree). to check whether participants perceived themselves as representative or not, e.g. ‘I had to represent the wishes of my group members’, ‘I negotiated on behalf of other people’, ‘I negotiated only for myself (reverse coded)’, Cronbach’s α = .93.

2.2 Results and Discussion

A one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with the manipulation check, moral disengagement and the SINS scale as dependent variable was conducted. The overall multivariate effect of role was significant, F (4, 168) = 68.43, p < .001, η 2p = .62. The manipulation check was significant; representatives indicated that they negotiated on behalf of a group more than non-representatives, F(1, 171) = 269.71, p < .001, η 2p = .61, M = 5.86, SD = 0.91 and M = 2.80, SD = 1.46 respectively.

Supporting Hypothesis 1, representatives were more willing (M = 3.54, SD = 1.26) to employ unethical negotiation behavior than non-representatives (M = 3.03, SD = 1.17, F [1, 171] = 7.66, p = .006, η 2p = .04), however there was no effect on moral disengagement, (Mrep = 5.07, SD = 1.71, Mno-rep = 4.87, SD = 1.58, F [1, 171] = 0.60, p = .44, η 2p = .003).

This experiment provides first evidence that the mere presence of a constituency suffices to foster unethical negotiation tactics. This is a noteworthy finding that alerts us about a previously unknown and—apparently—inherent threat of representative negotiations. As such, it is not based on any form of intervention, but solely stems from the—very common—situation of negotiating as a representative. At the same time, the quiet presence of a constituency does not seem to provide enough cognitive replacement of responsibility and justification to experience moral disengagement.

In the next experiment, we investigate the role of explicit constituency communication and test Hypothesis 2. Additionally, we explore whether unethical choice increases linearly with the size of the constituency faction communicating liberal attitudes towards unethical behavior, or whether a minority communicating either liberal or strict attitudes would suffice to sway representatives in either direction. This exploratory extension of our research design was motivated by extant evidence that a minority advocating competitive values disproportionally affects representatives’ competitive behavior (Steinel et al. 2009). Given the higher moral threshold for unethical behavior, we were interested in investigating the likelihood that a similar pattern may nonetheless apply here.

3 Experiment 2

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Sample and Design

One hundred seventy-one undergraduate students from a Western European university (69.6% female, Mean age 19.90 years, SD = 3.88) participated in a lab experiment where they were randomly allocated to one of six conditions varying in the constituency members’ attitudes toward unethical tactics: liberal or conservative (from none of the constituency members communicating a liberal attitude toward unethical tactics to all four, and a control condition without information regarding constituencies’ attitudes toward unethical tactics).

3.1.2 Procedure and Manipulation of Constituencies’ Ethical Values

Participants were seated in separate cubicles and were instructed to imagine representing a group in a negotiation. No context regarding the topic of the negotiation was provided. They learned that each of their four constituency members had left a message for them about their preferred negotiation strategy. These messages were in fact prefabricated. We circulated sixteen messages, based on items in the lie acceptability scale (Oliveira and Levine 2008): Eight reflecting liberal, and eight reflecting strict attitudes towards unethical behavior (see Table 1).

After receiving the messages, nine items of the SINS scale (Robinson et al. 2000) were administered. Participants were compensated with course credit and debriefed.Footnote 1

3.1.3 Measures

We assessed negotiators’ willingness to use unethical negotiation tactics with the false promises, inappropriate information gathering, and misrepresentation subscales of the SINS scale (same as Experiment 1, Robinson et al. 2000, Cronbach’s α = .87).

3.2 Results and Discussion

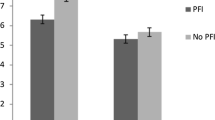

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a main effect of condition on the willingness to use unethical negotiation tactics, F(5, 165) = 11.40, p < .001, η 2p = .26. Willingness to use unethical tactics in the control condition fell in between the other conditions (M = 3.67, SD = 0.24) and was higher than when none (Mean difference = 1.17, SE = 0.34, p = .001, 95% CI [.51, 1.83]) or one (Mean difference = 0.81, SE = 0.34, p = .02, 95% CI [.15, 1.47]) of the constituency members communicated a liberal attitude toward unethical tactics, yet lower than when three (Mean difference = − 0.71, SE = 0.33, p = .04, 95% CI [− 1.36, − .05]) or all (Mean difference = − 0.83, SE = 0.34, p = .01, 95% CI [− 1.50, − .17]) did. To test Hypothesis 1 we removed the participants in the control condition from the analysis to fit a linear curve by regressing willingness to use unethical tactics on the constituency composition conditions, with an increase in number of constituents communicating a liberal attitude towards unethical conduct. Supporting Hypothesis 2, the more members communicated a liberal attitude towards unethical tactics, the more willing negotiators were to employ such unethical tactics, F(1, 141) = 52.15, p < .001, R2 = .27 (see Fig. 1). This increase was linear, showing that a minority of constituency members communicating liberal attitudes did not disproportionally affect representatives’ unethical choice. Experiment 3 aims to replicate this finding with a measure of actual negotiation behavior instead of mere intentions.

4 Experiment 3

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Sample and Design

One hundred nine undergraduate students from a Western European university (65.1% female, Mean age 21.60 years, SD = 2.58) participated in a lab experiment for research credit as part of a student research project with a 3 week data collection period. They were randomly allocated to one of three (constituency: low unethical endorsement, high unethical endorsement, or neutral) conditions.

4.1.2 Procedure, Task and Manipulation of Constituency

We used an intergroup negotiation task employed in previous research (e.g., Van Kleef et al. 2007). Upon arrival in the laboratory, participants learned that they would take part in a one-shot negotiation as part of a group with another group about advertisement campaigns for five different cars. To enhance credibility of real constituent members, they took part in a preprogrammed introductory chat session before being, allegedly randomly, appointed as group representative. After reading the instructions, participants participated in a second chat session, where they received preprogrammed messages from their four alleged constituency members. These messages either communicated mainly liberal attitudes towards unethical strategies, mainly strict attitudes towards unethical strategies, or had no reference to any preferred strategy (the neutral condition). During each negotiation round, participants were told to choose whether or not to send a message from a set of pre-formulated texts to their counterpart. These messages were grouped under eight categories, two of which explicitly contained unethical strategies (category ‘misrepresentation’ and category ‘false promises’, see the Appendix). We included other categories to provide participants with a large variety of options (including cooperative, competitive and neutral messages) to prevent steering them towards choosing unethical messages. Participants always made the first offer in the negotiation and chose whether or not to send a pre-formulated message accompanying their offer. The negotiation partner was preprogrammed and the negotiation stopped if a fixed target value was reached or after six negotiation rounds without agreement. After the negotiation, participants were thanked, received research credit, and were debriefed.Footnote 2

4.1.3 Measures

The main dependent variable was the number of unethical messages sent. Note that by picking one of the unethical messages, participants were aware that they were making a false promise or misrepresenting information as they explicitly selected this category. The messages were based on the SINS scale (Robinson et al. 2000). For example, ‘I only receive 100 points for this proposal, I really can’t accept that’, (misrepresentation of information) or ‘I will really stick to our terms of agreement’ (false promises).Footnote 3

The manipulation check of constituency endorsement consisted of five items (1 Fully disagree; 9 Fully agree), e.g. ‘My constituency thought it was important that I would be honest during the negotiation’, Cronbach’s α = .96.

4.2 Results and Discussion

4.2.1 Manipulation check

A one-way ANOVA supported the manipulation check, F(2, 106) = 116.70, p < .001, η 2p = .69. Negotiators in the liberal attitudes condition (M = 3.46, SD = 1.13) rated their constituency as less ethical than in the neutral condition (M = 5.26, SD = 1.25, Contrast estimate = − 1.803, SE = 0.28, p < .001, 95% CI [− 2.36, − 1.25]), and negotiators in the strict attitudes condition rated their constituency as more ethical (M = 7.30, SD = 1.05) than in the neutral condition (Contrast estimate = − 2.03, SE = 0.28, p < .001, 95% CI [1.48, 2.58]).

4.2.2 Hypothesis Testing

A one-way ANOVA supported Hypothesis 2: unethical messages differed between the liberal attitudes condition (M = 3.87, SD = 4.17), the neutral condition, (M = 2.79, SD = 2.78) and the strict attitudes endorsement condition (M = 1.76, SD = 2.42, F[2, 106] = 4.30, p = .016, η 2p = .08). A priori contrast analyses revealed a difference only between negotiators with a strict attitude constituency and those with a liberal attitude constituency (Contrast Estimate = 2.11, SE = .72, p = .004, 95% CI [.68, 3.54]); comparisons with the neutral condition were not significant. Results of Experiment 2 and 3 corroborated Hypothesis 2. Representatives were more willing to use unethical tactics when constituency members showed liberal attitudes towards these. This effect was replicated operationalizing unethical tactics as actual behavior.

5 Discussion Experiment 3 and Introduction to Experiments 4a and 4b

Results of Experiment 2 and 3 corroborated Hypothesis 2. Representatives were more willing to use unethical tactics when constituency members showed liberal attitudes towards these. This effect was replicated operationalizing unethical tactics as actual behavior.

We next tested whether moral disengagement could explain the increase in unethical behavior when the constituency has a more liberal stance towards such tactics (Hypothesis 3), and whether constituencies’ communicated preference for competitive tactics affected unethical behavior (Hypothesis 4). To test the robustness of the adverse effect of a constituency advocating a competitive approach on unethical behavior, we conducted two similar experiments with different samples (Experiments 4a and 4b).

5.1 Methods

5.1.1 Sample and Design

In Experiment 4a, 167 undergraduate students of a Western European university completed the study online in exchange for research credit during a 2 weeks data collection period (Mean age = 27.2 years, SD = 13.12, 68.3% female). No participants were excluded. Participants were randomly allocated to one of three constituency conditions: liberal attitudes towards unethical tactics, strict attitudes towards unethical tactics, and favorable attitudes towards competitive tactics.Footnote 4

In Experiment 4b we aimed to replicate the results of Experiment 4a with a fully powered sample via Prolific Academic in exchange for 1 GBP. Power analysis revealed a required sample size of 303 (assuming small effect sizes and a power of 1 − ß = .8). Our final sample consisted of all 322 subjects that completed the experiment (65.5% female, Mean age = 32.46 years, SD = 10.67. They were randomly assigned to one of the same three conditions.Footnote 5

5.1.2 Procedure and Negotiation Task

The same negotiation scenario as for Experiment 1 was used, with participants negotiating with another project team about their campaign idea, where they had the opportunity to lie about previous collaborations and the time it had taken them to devise their initial idea. Participants were told that they would represent other participants, who had selected a message from a list. Participants were presented with a list of eight messages, consisting of either four messages indicating a liberal and four indicating a strict attitude towards unethical strategies, or of four messages endorsing competitive and four endorsing cooperative strategies (see Table 2). Depending on condition, four of these messages were bold-faced and supposedly left by their constituency members (three strict and one liberal toward unethical behavior, three liberal and one strict toward unethical behavior, four competitive). The study ended with assessing the dependent variables and demographics.

5.1.3 Measures

Moral disengagement was measured with the six-item measure by Shu et al. (2011) and adjusted to refer explicitly to the negotiation in Experiment 4a (e.g., ‘rules should be flexible enough to be adapted in different situations, such as this negotiation’, Cronbach’s α = .74). Experiment 4b used the original scale, Cronbach’s α = .82.

Willingness to engage in unethical behavior was measured with the same 9 items from the SINS scale as used in Experiment 1 and 2 (Cronbach’s α = .88 and .90 in Experiment 4a and 4b, respectively).

Separate manipulation checks were assessed: Four items assessed constituencies’ attitudes towards unethical conduct, for example ‘My team members thought that immoral behavior was allowed during the negotiation’ (Cronbach’s α = .89 and .91 in Experiment 4a and 4b, respectively). Constituencies’ competitive endorsement was assessed with three items, for example: ‘My team members had a competitive mindset’ (Cronbach’s α = .83 and .65 in Experiment 4a and 4b, respectively). All items were assessed on 7 point scales (1 = completely disagree; 7 = completely agree).

5.2 Results and Discussion

5.2.1 Manipulation Checks

For Experiment 4a, two one-way ANOVAs following a MANOVA of constituency endorsement (high unethical, low unethical, competitive) on the two manipulation check scales showed the expected main effects on perceived unethicality of the constituency, F(2, 163) = 39.39, p < .001, η 2p = .33 as well as on perceived competitiveness of the constituency, F(2, 163) = 97.78, p < .001, η 2p = .55. For means, standard deviations, and contrast estimates, see Table 3.

For Experiment 4b, ANOVAs on the manipulation check scales revealed the expected main effects: of constituency communication on the extent to which the constituency was perceived as endorsing unethical values, F(2, 316) = 161.39, p < .001, η 2p = .51, and of constituency communication on the perception of endorsement of competitive values in the constituency, F (2, 316) = 102.62, p < .001, η 2p = .40. For means, standard deviations, and contrast differences, see Table 3. All manipulations were successful in both experiments.

5.2.2 Hypotheses Testing

Supporting Hypothesis 2 in Experiment 4a ANOVAs revealed a main effect of constituency communication on unethical behavior, F(2, 163) = 13.14, p < .001, η 2p = .14, with more unethical behavior in the liberal than in the strict attitudes towards unethical values condition (Contrast Estimate = .96, p < .001, 95% CI [1.35, .57]) and, similarly, more unethical behavior in the competitive condition than in the strict attitudes condition (Contrast Estimate = .72, p < .001, 95% CI [1.10, .35]), supporting Hypothesis 4a. For means and standard deviations, see Table 4. There was no difference in unethical behavior whether the constituency had a liberal attitude towards unethical tactics or when it favored competitive behavior (Contrast Estimate = − .24, p = .21, 95% CI [− .61, .14]).

For moral disengagement, there was a similar main effect, F(2, 163) = 8.55, p < .001, η 2p = .10. Contrast analyses showed more moral disengagement in the liberal attitudes compared to strict attitudes towards unethical tactics condition (Contrast Estimate = − .86, p < .001, 95% CI [− 1.28, − .45]), and in the competitive compared to strict attitudes condition (Contrast Estimate = − .45, p = .03, 95% CI [− .85, − .04]). For means and standard deviations, see Table 4. Additionally, negotiators in the liberal attitudes towards unethical tactics condition reported higher moral disengagement than negotiators in the competitive condition (Contrast Estimate = .42, p = .04, 95% CI [.02, .82]).

Using a Bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples and multicategorical independent variables (Hayes 2017), the bias-accelerated model (5000 resamples) showed moral disengagement to mediate the effect of the liberal and strict attitudes towards unethical tactics on unethical behavior, estimate = − .28, SE = .08, 95% CI [− .45, − .14]. Finally, moral disengagement also mediated the effect of the constituency favoring a competitive approach versus having strict attitudes towards unethical tactics on unethical behavior, estimate = .29, SE = .12, 95% CI [.04, .56]. These results support Hypothesis 3 and 4b.

Results of Experiment 4b are highly similar. Supporting Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 4a, an ANOVA with constituency communication on unethical behavior (F[2, 319] = 18.46, p < .001, η 2p = .10) and subsequent contrast analyses showed that negotiators in the liberal attitudes condition were more willing to use unethical tactics than negotiators in the strict attitudes condition (Contrast Estimate = − .82, p < .001, 95% CI [− 1.09, − .54]) but did not differ significantly in their willingness to use unethical tactics from negotiators with a constituency favoring competitive tactics, Contrast Estimate = − .19, p = .18, 95% CI [− .09, .48]). Negotiators with a constituency favoring competitive tactics were similarly more likely to use unethical tactics than negotiators in the strict attitudes towards unethical tactics condition (Contrast Estimate = − .62, p < .001, 95% CI [− .91, − .34]). For means and standard deviations, see Table 5.

A main effect of constituency communication on moral disengagement, F(2, 319) = 12.23, p < .001, η 2p = .07 was followed up by contrast analyses showing more moral disengagement in the liberal as compared to the strict attitudes towards unethical tactics condition, Contrast Estimate = − 1.04; p < .001, 95% CI [− 1.47, − .61]). However, the liberal attitudes condition did not differ significantly from the competitive condition (Contrast Estimate = .31, p = .17, 95% CI [− .13, .74]). Negotiators in the competitive condition did show more moral disengagement than negotiators in the strict attitudes condition, Contrast Estimate = − .74, p < .001, 95% CI [− 1.19, − .30]). For means and standard deviations, see Table 5.

Finally, to test for the mediation predicted in H3 and H4b, we investigated the indirect effect of constituency communication on unethical behavior via moral disengagement using the same Bootstrapping procedure. There was an indirect effect of the liberal versus strict attitudes towards unethical tactics on unethical choice via moral disengagement, estimate = .27, SE = .06, 95% CI [.16, .40]. Moreover, moral disengagement also mediated the difference between the competitive and the strict attitudes condition, estimate = .34, SE = .10, 95% CI [.14, .56]. Thus, in accordance with our hypotheses, a constituency favoring competitive behavior affected representatives’ unethical negotiation choice in much the same way as a constituency with liberal attitudes towards unethical tactics does: Negotiators felt freed from their moral compass, allowing them to morally disengage and thus display more unethical behavior in the negotiations. In sum, in Experiments 4a and 4b, we showed moral disengagement to be an important mechanism allowing negotiators to display this unethical behavior—whether their constituency expressed liberal attitudes towards unethical behavior, or even merely favored competitive conduct.

Interestingly, representatives with a constituency endorsing competitive behavior increased unethical behavior over those with a constituency with a strict attitude towards unethical conduct, but did not differ from those with a liberal attitude in both studies. This trend is also reflected in the levels of moral disengagement: only in one of the two studies was moral disengagement significantly stronger in the liberal attitudes towards unethical conduct than in the competitive endorsement condition. Thus, competitive endorsement indeed seems to effectively initiate the “slippery slope” of unethical conduct.

6 General Discussion

In negotiations, where accepted competitive and undesired unethical behavior increase favorable outcomes (Crampton and Dees 1993; Olekalns et al. 2014), curtailing unethical decisions is challenging. In four experiments, we show how the presence of a constituency can increase the use of unethical negotiation tactics by representatives (Experiment 1). Specifically, a constituency communicating liberal attitudes towards unethical conduct influences representatives to justify transgressions and morally disengage from their behavior, resulting in increased willingness to and actual use of unethical negotiation tactics (Experiment 2–4). More alerting, a constituency endorsing competitive conduct suffices for representatives to engage in unethical tactics, and to internally justify this behavior. Because competitive constituencies are very common in business settings (Bazerman et al. 2000; Lewicki et al. 2015), our results provide important insights for the implementation of ethical organizations and advancing the research field.

First, while research on unethical behavior in general and unethical negotiation behavior specifically has considered a large number of factors that decrease or enhance unethical conduct (Aquino 1998; Cohen 2010; Schweitzer et al. 2005; Tasa and Bell 2017), surprisingly no research has investigated the pivotal role of the people behind the negotiator, namely, the constituency. By integrating literature from representative negotiations with literature on unethical behavior, we show the relevance of the constituencies’ presence and communication for the use of unethical tactics. Additionally, we show that constituencies can push representatives down the slippery slope by (a) mere presence, (b) eliciting moral disengagement through endorsing competitive tactics and (c) eliciting moral disengagement through explicitly communicating a liberal attitude towards unethical behavior.

Second, we identify moral disengagement as the mechanism driving this process (Experiment 4ab): When the constituency shows a liberal stance regarding unethical conduct or even merely endorses competitive behavior, negotiators’ tolerance for unethical behavior increases. Moral disengagement appears to be a process predicting and explaining unethical behavior, rather than a general individual propensity and correlate of unethical behavioral tactics (Moore et al. 2012). This complements previous research on state characteristics of moral disengagement, showing how situational manipulations influence moral disengagement (Boardley and Kavussanu 2009; Hodge and Lonsdale 2011; Shu et al. 2011).

6.1 Implications

Admittedly, explicitly communicating liberal attitudes towards unethical negotiation tactics may be rather rare and few organizations will send their negotiators out to deceive other negotiation parties. However, our findings show that any expression of attitudes towards unethical behavior matters, and directly enables negotiators to justify unethical behavior for themselves. Moreover, our findings in Experiment 4 alert us that the slippery slope to unethical negotiation behavior is prone to be unintentionally invoked without direct reference to unethical values. The mere endorsement of competitive tactics, which are very common in negotiations, in businesses, politics and labor relations alike (Bazerman et al. 2000; Lewicki et al. 2015), invites unethical tactics and elicits moral disengagement to a comparable extent as the communication of liberal attitudes towards unethical tactics do. The risk of ethical transgressions in negotiation may further increase with any other contextual factors that trigger the process of moral disengagement. Future research should further clarify this troubling mechanism to better guide practitioners to implement ethical guidelines throughout their workforce.

Particularly, future research should investigate potential countermeasures to overcome the effect of unwanted implicit or explicit approval of unethical behavior by some constituency members—which may be hard to control in large and diverse workforces. For example, organization-wide ethicality rules may set a barrier against unethical conduct in negotiations and even counteract explicit endorsement for a specific negotiation. This would be in line with research by Aquino (1998), who showed that emphasis on organizations’ ethical values reduced the use of deception in negotiations. Whether such general ethical values are salient enough to overcome the effect of constituencies’ communicated attitudes about competitive or unethical behavior remains an open research question.

To avoid ethical transgressions in negotiation, organizations should also reconsider their practice regarding the endorsement of competition in negotiations. Although competitive or hardline bargaining positively impacts economic gain in negotiations (Hüffmeier et al. 2014), it also elicits moral disengagement and associated unethical behavior in our experiments. Fortunately, there is much research suggesting that a cooperative mindset and a cooperative constituency can help to gain high outcomes in negotiations for both parties, especially when the negotiation consists of multiple issues that differ in importance for each party, making log-rolling feasible (Aaldering and Ten Velden 2018; De Dreu et al. 2000).

Based on our studies, we recommend that organizations carefully educate their workforce to think twice before endorsing either competitive or unethical values in negotiations. Promoting competition in negotiations may be tempting in order to secure one’s own interests in business transactions. However, every employee that is involved in a negotiation—whether directly as representative negotiator or indirectly as constituent in the background—can be responsible for ethical transgressions in negotiations. While approving competitive or unethical values can be personally beneficial, it comes with a price for the organization.

Notes

We also assessed the following constructs: need to belong, social value orientation, moral identity, feelings of entitlement, and participants’ reflection on their motivation to fulfill the wishes of their constituency. Materials are available from the first author upon request.

We also assessed the following constructs: moral identity, entitlement, participants’ reflection on their motivation to fulfill the wishes of their constituency and the extent to which they used the presence of their constituency as justification for their unethical negotiation behavior. Materials are available from the first author upon request.

Three other scales adapted from the SINS scale were operationalized with messages from which the participants could choose: Competitive bargaining tactics and feigning positive and negative affect. Because neither of these can be interpreted as unequivocally measuring unethical tactics, they were not included in the analyses. Materials are available from the first authors upon request.

In this experiment, we also explicitly manipulated outcome pressure; whether the participants felt pressure to reach high outcomes or not. The manipulation was unsuccessful according to our manipulation check and did not affect any of the dependent variables. We therefore do not report it in the text. Analyses are available from the first author upon request.

In this experiment, we also explicitly manipulated personal responsibility; whether the participants felt personally responsible for their behavior or whether the constituency was mainly responsible. The manipulation did not affect any of the dependent variables. We therefore do not report it in the text. Analyses are available from the first author upon request. 26 participants incorrectly recalled the number of weeks. Removing them does not change results.

References

Aaldering H, De Dreu CK (2012) Why hawks fly higher than doves: intragroup conflict in representative negotiation. Group Process Intergroup Relat 15:713–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212441638

Aaldering H, Ten Velden FS (2018) How representatives with a dovish constituency reach higher individual and joint outcomes in integrative negotiations. Group Process Intergroup Relat 21:1–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216656470

Aquino K (1998) The effects of ethical climate and the availability of alternatives on the use of deception during negotiation. Int J Confl Manag 9:195–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022809

Ardichvili A, Mitchell JA, Jondle D (2009) Characteristics of ethical business cultures. J Bus Ethics 85:445–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9782-4

Bazerman MH (2011) Bounded ethicality in negotiations. Negot Confl Manag Res 4:8–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-4716.2010.00069.x

Bazerman MH, Curhan JR, Moore DA, Valley KL (2000) Negotiation. Annu Rev Psychol 51:279–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.279

Benton AA, Druckman D (1973) Salient solutions and the bargaining behavior of representatives and nonrepresentatives. Int J Group Tens 3:28–39

Boardley ID, Kavussanu M (2009) The influence of social variables and moral disengagement on prosocial and antisocial behaviors in field hockey and netball. J Sports Sci 27:843–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410902887283

Borkowski SC, Ugras YJ (1998) Business students and ethics: a meta-analysis. J Bus Ethics 17:1117–1127. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005748725174

Cohen TR (2010) Moral emotions and unethical bargaining: the differential effects of empathy and perspective taking in deterring deceitful negotiation. J Bus Ethics 94(4):569–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0338-z

Cohen TR, Panter AT, Turan N, Morse L, Kim Y (2014) Moral character in the workplace. J Pers Soc Psychol 107:943. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037245

Crampton PC, Dees JG (1993) Promoting honesty in negotiation. Bus Ethics Q 3:359–394. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857284

De Dreu CKW, Gelfand MJ (eds) (2007) The psychology of conflict and conflict management in organizations. Jossey Bass, San Francisco

De Dreu CK, Weingart LR, Kwon S (2000) Influence of social motives on integrative negotiation: a meta-analytic review and test of two theories. J Pers Soc Psychol 78:889. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.889

De Dreu CKW, Aaldering H, Saygi O (2014) Conflict within and between groups. In: Dovidio J, Simpson J (eds) APA handbook of interpersonal and group relations, vol 2. APA Press, Washington, DC, pp 151–176

Dees JG, Cramton PC (1991) Shrewd bargaining on the moral frontier: toward a theory of morality in practice. Bus Ethics Q 1:135–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857260

Detert JR, Treviño LK, Sweitzer VL (2008) Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J Appl Psychol 93(2):374–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.374

Druckman D, Solomon D, Zechmeister K (1972) Effects of representational role obligations on the process of children’s distribution of resources. Sociometry 35(3):387. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786502

Druckman D (1977) Boundary role conflict: negotiation as dual responsiveness. J Confl Resolut 21:639–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200277702100406

Fleck D, Volkema RJ, Pereira S (2016) Dancing on the slippery slope: the effects of appropriate versus inappropriate competitive tactics on negotiation process and outcome. Group Decis Negot 25(5):873–899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-016-9469-7

Hayes AF (2017) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford publications, New York

Hodge K, Lonsdale C (2011) Prosocial and antisocial behavior in sport: the role of coaching style, autonomous vs. controlled motivation, and moral disengagement. J Sport Exerc Psychol 33(4):527–547. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.4.527

Hüffmeier J, Freund PA, Zerres A, Backhaus K, Hertel G (2014) Being tough or being nice? A meta-analysis on the impact of hard-and softline strategies in distributive negotiations. J Manag 40:866–892. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311423788

Hüffmeier J, Zerres A, Freund PA, Backhaus K, Trötschel R, Hertel G (2019) Strong or weak synergy? Revising the assumption of team-related advantages in integrative negotiations. J Manag 45(7):2721–2750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318770245

Kaufman A (2002) Managers’ double fiduciary duty: to stakeholders and to freedom. Bus Ethics Q 12:189–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857810

Kish-Gephart JJ, Harrison DA, Treviño LK (2010) Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J Appl Psychol 95:1

Lewicki RJ, Robinson RJ (1998) Ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: an empirical study. J Bus Ethics 17:665–682. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005719122519

Lewicki RJ, Stark N (1996) What is ethically appropriate in negotiations: an empirical examination of bargaining tactics. Soc Justice Res 9:69–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02197657

Lewicki RJ, Saunders DM, Barry B (2015) Negotiation. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Martin KD, Cullen JB (2006) Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: a meta-analytic review. J Bus Ethics 69:175–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9084-7

Mazar N, Amir O, Ariely D (2008) The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of self-concept maintenance. J Mark Res 45(6):633–644. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.6.633

Moore C, Detert JR, Klebe Treviño L, Baker VL, Mayer DM (2012) Why employees do bad things: moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Pers Psychol 65:1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

Mosterd I, Rutte CG (2000) Effects of time pressure and accountability to constituents on negotiation. Int J Confl Manag 11(3):227–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022841

Olekalns M, Smith PL (2007) Loose with the truth: predicting deception in negotiation. J Bus Ethics 76:225–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9279-y

Olekalns M, Kulik CT, Chew L (2014) Sweet little lies: social context and the use of deception in negotiation. J Bus Ethics 120:13–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1645-y

Oliveira CM, Levine TR (2008) Lie acceptability: a construct and measure. Commun Res Rep 25:282–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090802440170

Pinkley RL, Griffith TL, Northcraft GB (1995) Fixed pie a la mode—information-availability, information-processing, and the negotiation of suboptimal agreements. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 62:101–112. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1035

Rest J (1986) Development in judging moral issues. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Robinson RJ, Lewicki RJ, Donahue EM (2000) Extending and testing a five factor model of ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: introducing the SINS scale. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200009)21:6%3C649:AID-JOB45%3E3.0.CO;2-%23

Schweitzer ME, Croson R (1999) Curtailing deception: the impact of direct questions on lies and omissions. Int J Confl Manag 10:225–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022825

Schweitzer ME, DeChurch LA, Gibson DE (2005) Conflict frames and the use of deception: Are competitive negotiators less ethical? J Appl Soc Psychol 35:2123–2149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02212.x

Shu LL, Gino F, Bazerman MH (2011) Dishonest deed, clear conscience: when cheating leads to moral disengagement and motivated forgetting. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 37:330–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211398138

Siegel S, Fouraker LE (1960) Bargaining and group decision making: experiments in bilateral monopoly. McGraw-Hill, New York

Spiller R (2000) Ethical business and investment: a model for business and society. J Bus Ethics 27:149–160. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006445915026

Steinel W, De Dreu CKW, Ouwehand E, Ramirez-Marin JY (2009) When constituencies speak in multiple tongues: constituency heterogeneity and representative negotiation. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 109:67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.12.002

Tasa K, Bell CM (2017) Effects of implicit negotiation beliefs and moral disengagement on negotiator attitudes and deceptive behavior. J Bus Ethics 142:169–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2800-4

Thielmann I, Hilbig BE (2018) Daring dishonesty: on the role of sanctions for (un)ethical behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol 79:71–77

Thielmann I, Hilbig BE (2019) No gain without pain: the psychological costs of dishonesty. J Econ Psychol 71:126–137

Thompson L, Peterson E, Brodt SE (1996) Team negotiation: an examination of integrative and distributive bargaining. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1997.2747

Van Kleef GA, Steinel W, Van Knippenberg D, Hogg MA, Svensson A (2007) Group member prototypicality and intergroup negotiation: how one’s standing in the group affects negotiation behavior. Br J Soc Psychol 46:129–152. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X89353

Volkema RJ, Fleck D, Hofmeister-Toth A (2004) Ethicality in negotiation: an analysis of attitudes, intentions, and outcomes. Int Negot 9(2):315–339

Walton R, McKersie B (1965) A behavioral theory of labor negotiations: an analysis of a social interaction system. McGraw-Hill, Ithaca, NY

Welsh DT, Ordóñez LD, Snyder DG, Christian MS (2015) The slippery slope: how small ethical transgressions pave the way for larger future transgressions. J Appl Psychol 100:114–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036950

Wildschut T, Insko CA (2007) Explanations of interindividual–intergroup discontinuity: a review of the evidence. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 18:175–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280701676543

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Each experiment was approved by the ethical review board of the university where the experiments were conducted. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in each study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The messages that participants could select in Experiment 3.

Category | Message |

|---|---|

Cooperative | I hope we manage to find a way together |

Let’s try to reach an agreement that’s good for both of us | |

Let’s try to reach a fair deal | |

I’m fine giving in here and there if that will help us to reach a better agreement | |

Competitive | This costs me an arm and a leg, I can’t make more concessions than this |

I’ve got a lot of time, I’ll wait until you start giving in more | |

I can’t go further than this. This is my final offer | |

If you don’t give in more this whole negotiation is pointless | |

Misrepresent information | I gave in a lot with my first offer, now you need to give in too |

I only receive 100 points for this proposal, I really can’t accept that | |

You pretend to make concessions, but those are not comparable to what I already gave in | |

I really receive way less than half with your proposal, can’t you give in a little bit! | |

False promises | I will reward you if you give into my wishes a bit now |

If we close a deal now in which I earn a lot, I will give you half of my profits | |

I will really stick to our terms of agreement | |

If you help me in the negotiation I can help you with designing the posters. | |

Pretend positive emotions | Please don’t take it personal, I really like you |

I understand it isn’t easy for you and I sympathize with you | |

I find it important for you too to reach a good agreement! | |

I’m happy to put effort to get a good deal for you too | |

Pretend negative emotions | You really make me anger with such an offer! |

This proposal makes me very sad | |

I think your offer is insulting | |

I am very unsatisfied with this proposal | |

Use of constituency | My constituency would never approve so I can’t give into you |

My constituency really wants me to gain more points | |

I would get fired by my constituency if I would agree with this | |

My constituency prohibits me to agree with a deal that will unfold so badly for them | |

Neutral | What do you think of this offer? |

I’m curious to hear your reply | |

Is this getting close? | |

Here is my new proposal |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aaldering, H., Zerres, A. & Steinel, W. Constituency Norms Facilitate Unethical Negotiation Behavior Through Moral Disengagement. Group Decis Negot 29, 969–991 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-020-09691-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-020-09691-1