Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze bidders’ behavior, comparing individuals and groups’ decisions within the dollar auction framework. This game induces subjects to fall prey into the paradigm of escalation, which is driven by agents’ commitment to higher and higher bids. Whenever each participant commits himself to a bid, the lower bidder, motivated by the wish to win as well as to defend his prior investment, finds it in his best interest to place a higher bid to overcome his opponent. The latter mechanism may lead subjects to overbid. We find that the Nash equilibrium of the game is only rarely attained. Second, we detect clean evidence that groups’ decisions are, on average, superior to individuals’ decisions. Learning over time is clearly evident, leading individuals to perform nearly as good as groups in the final rounds of the game.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

eBay auctions, mineral right auctions and corporate takeovers are widespread examples.

See Arkes and Blumer (1985).

While in the easy level of the task the majority of subjects can solve the problem, in the difficult version only a minority can succeed.

O’Neill et al. (2015) showed that “Face-to-face teams were more effective on all decision”.

During the experiment only group’s members can look at each other in the eye, and on the group’s screen, but they cannot look at other groups’ screen or other participant in the lab.

The ECU (Experimental Currency Unit) is the currency used in the experiment.

Of course, since there were no upper limits to bidding, subjects could potentially suffer massive losses. To mitigate this downside, subjects were previously involved in another experiment where they could only make a gain. After the two experiments, no subject ended up with a negative net profit.

While our partner design presents several upsides (e.g. in terms of providing multiple independent observations within a session), it may result in reputational effects and cooperation. For instance, subjects might alternate who bids the minimum and who does not. We control for this through a fixed effects logit model testing whether winning at t − 1 affects the probability of winning in t. No evidence of strategic cooperation is detected in both treatments, with the lagged binary variable (win_t − 1 exhibiting a coefficient of 0.55 and a p value of 0.128 in the individual treatment and a coefficient of 0.22 and a p value of 0.546 in the group treatment).

Since subjects in a $-auction experiment can loose money we run this experiment coupled with a public good game with strictly positive pay-off. In order to avoid wealth effects subjects did not received any feedback on their pay-off or other subjects’ contribution to the public good. The public good part lasted approximately 30 min and subjects earned 25 €.

This evidence is largely supported in the related literature. See, for example, Blinder and Morgan (2005).

Indeed, within dyad observations over time are likely to be more correlated than between dyad observations.

Starting from a pilot sample of 8 independent observations (dyads) per treatment, a power sample size (PSS) analysis led us to engage a sample of 20 independent observations in each condition, whose size ensured a power greater than 0.98 in the one sample mean tests and greater than 0.77 in the two sample mean tests. Details are available upon request.

Individual Losers: N = 20, t = 6.81, p = 0.00; Individual Winners: N = 20, t = 7.66, p = 0.00; Group Losers: N = 20, t = 4.33, p = 0.00; Group Winners: N = 20, t = 5.10, p = 0.00).

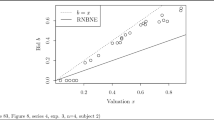

While inexperienced individuals present an expected RMSE of 12.07, inexperienced groups exhibit an expected RMSE of around 4.

References

Adams R, Ferreira D (2010) Moderation in groups: evidence from betting on ice break-ups in Alaska. Rev Econ Stud 77(3):882–913

Arkes HR, Blumer C (1985) The psychology of sunk cost. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 35(1):124–140

Blinder AS, Morgan J (2005) Are two heads better than one? monetary policy by committee. J Money Credit Bank 37(5):789–812

Bornstein G, Kugler T, Ziegelmeyer A (2004) Individual and group decisions in the centipede game: are groups more “rational” players? J Exp Soc Psychol 40(5):599–605

Briggs A (2013) The conflict of laws. OUP, Oxford

Casari M, Jackson C, Zhang J (2015) Same process, different outcomes: group performance in an acquiring a company experiment. Exp Econ 19(4):764–791

Charness G, Sutter M (2012) Groups make better self-interested decisions. J Econ Perspect 26(3):157–176

Cooper DJ, Kagel JH (2005) Are two heads better than one? team versus individual play in signaling games. Am Econ Rev 95(3):477–509

Cooper DJ, Kagel JH (2009) Equilibrium selection in signaling games with teams: forward induction or faster adaptive learning? Res Econ 63(4):216–224

Fischbacher U (2007) Z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Fréchette GR (2012) Session-effects in the laboratory. Exp Econ 15(3):485–498

Janis IL (1982) Groupthink: psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes, vol 349. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):263–291

Kerr NL, Maccoun RJ, Kramer GP (1996) Bias in judgment: comparing individuals and groups. Psychol Rev 103(4):687–719

Kocher MC, Sutter M (2005) The decision maker matters: individual versus group behaviour in experimental beauty contest games. Econ J 115(500):200–223

Kocher M, Strauss S, Sutter M (2006) Individual or team decision-making—causes and consequences of self-selection. Games Econ Behav 56(2):259–270

Leavitt H (1975) Suppose we took groups seriously. In: Cass EL, Zimmer FG (eds) Man and work in society. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, pp 67–77

Migheli M (2012) It is not just escalation: the one dollar game revisited. J Behav Exp Econ 41(4):434–438

Morone A, Morone P (2008) Guessing games and people behaviours: what can we learn? In: Abdellaoui M, Hey JD (eds) Advances in decision making under risk and uncertainty. Springer, Berlin, pp 205–217

Morone A, Morone P (2010) Boundary and interior equilibria: what drives convergence in a ‘beauty contest’? Econ Bull 30(3):2097–2106

Morone A, Morone P (2014) Estimating individual and group preference functionals using experimental data. Theor Decis 77(3):403–422

Morone A, Morone P, Germani AR (2014) Individual and group behavior in the traveler’s dilemma: an experimental study. J Behav Exp Econ 49(3):1–7

Murnighan JK (2002) A very extreme case of the dollar auction. J Manag Educ 26(1):56–69

O’Neill B (1986) International escalation and the dollar auction. J Confl Resolut 30(1):33–50

O’Neill TA, Hancock SE, Zivkov K, Larson NL, Law SJ (2015) Team decision making in virtual and face-to-face environments. Group Decis Negot 23(1):1–26

Shubik M (1971) The dollar auction game: a paradox in noncooperative behavior and escalation. J Confl Resolut 15(1):109–111

Shupp RS, Williams AW (2008) Risk preference differentials of small groups and individuals. Econ J 118(525):258–283

Staw BM (1981) The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Acad Manag Rev 6(4):577–587

Sutter M (2005) Are four heads better than two? an experimental beauty-contest game with teams of different size. Econ Lett 88(1):41–46

Sutter M, Kocher MG, Strauss S (2009) Individuals and teams in auctions. Oxf Econ Pap 61(2):380–394

Teger AI (1980) Too much invested to quit. Pergamon Press, New York

Temerario T (2014) Individual and group behaviour toward risk: a short survey. Working Paper

Thaler R (1980) Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. J Econ Behav Organ 1(1):39–60

Thaler RH (1988) Anomalies: the winner’s curse. J Econ Perspect 2(1):191–202

Funding

Funding was provided by Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro (IT) (Progetto Idea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

See Table 4.

Appendix D

Period by period comparison between actual and simulated groups’ bids for losers. See Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14.

Appendix E

Period by period comparison between actual and simulated groups’ bids for winners. See Tables 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morone, A., Nuzzo, S. & Caferra, R. The Dollar Auction Game: A Laboratory Comparison Between Individuals and Groups. Group Decis Negot 28, 79–98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-018-9595-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-018-9595-5