Abstract

The journal and in particular the resource reviews have been running for 10 years. There are a number of activities being planned to celebrate. However it is a good time to revisit our original and updated goals again [(Langdon, Genet Progrm Evolvable Mach 1(1/2):165–169 (2000); Langdon and Gustafson, Genet Program Evolvable Mach 6(2):221–228 (2005)], compare them with what the journal has achieved and make new plans. "Books" section onwards gives up to date statistics on the genetic programming and evolvable hardware literature and electronic resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Ten years of resource reviews

Excluding special issues and 10(3), every issue of GP/EM contained at least one review, making a total of 51. It was intended from the start that these would cover, not just books, but “resources” in the wider sense, particularly, web pages, on-line resources, packages and products [1, 2].

We have reviewed 36 books, 10 edited collections, and two conference/workshop proceedings. (It has been agreed that a journal like GP/EM is not appropriate for immediate dissemination, and so we don’t expect to review any more conferences or workshops, since many of their results are quickly updated. Instead electronic newsletters, like SIGEvolution, have carried short reviews of a number of events.) We have also published an article on Internet-based resources, one on software (albeit covering three packages) and reviewed one product. Topics have included not only genetic programming (21) evolvable hardware (7) and genetic algorithms (5) but also particle swarm optimisation (3), artificial development and embryos (2) robotics (2), Ant colony Optimisation, evolutionary programming, data mining, evolutionary design and art. Reviews have also included books on DNA computing (2), quantum computing, cellular automata, intelligent bioinformatics and the history of artificial intelligence. Articles have been written by authors based in the USA (13), the UK (11), Canada (7), Spain (3), Australia (3), Sweden (2), France (2), Ireland (2), Brazil (2), New Zealand, Singapore, Germany, Holland, Finland, Mexico, Chile and Argentina.

Recent reviews have continued the trend to reviewing exciting high-quality current books from adjacent evolutionary topics as well as from genetic programming and evolvable hardware. There have been reviews of books on genetic algorithms, intelligent swarms, DNA computing and developmental systems, as well as applications, such as bioinformatics and robotics. However there have been no recent reviews of non-book resources.

It is disapointing that although twelve commercial packages have been considered, only one has led to a review. Other areas where perhaps we should have more reviews include academic tools (3 so far) and the Internet (1). The world wide web contains a bewildering array of online teaching aids and video clips relevant to our field. However the inevitable publishing time lag and the lack of permanency of www resources makes scholarly reviews of online resources problematic.

We continue to receive a little feedback from readers, which continues to be positive. In keeping with readers’ suggestions we continue to limit reviews to about two pages. We will try to keep reviews short even if moves to electronic publication reduce pressure on page limits.

2 Books

More than 39 GP books on GP have been published in English and at least 6 in foreign languages. An interesting trend is to make books available via the Internet. A further 4 books are only or principally available on line. Books reviewed in Genetic Progrmming and Evolvable Machines are shown with *.

2009

-

Robert Plotkin. The Genie in the Machine: How Computer-Automated Inventing is Revolutionizing Law and Business. Stanford University Press, USA.

-

Hitoshi Iba, Yoshihiko Hasegawa and Topon Kumar Paul. Applied Genetic Programming and Machine Learning. CRC.

-

Michael Affenzeller, Stefan Wagner, Stephan Winkler, and Andreas Beham. Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming: Modern Concepts and Practical Applications. CRC.*

-

Anthony Brabazon and Michael O’Neill, editors. Natural Computing in Computational Finance (Volume 2), Springer.

-

Ian Dempsey, Michael O’Neill, and Anthony Brabazon. Foundations in Grammatical Evolution for Dynamic Environments. Springer.

-

Shaobo Li and Jianjun Hu. Genetic Programming and Creative Design of Mechatronic Systems. China Machine Press.

-

Sean Luke. Essentials of Metaheuristics . Available at http://www.cs.gmu.edu/~sean/books/metaheuristics/.

2008

-

Anthony Brabazon and Michael O’Neill, editors. Natural Computing in Computational Finance. Springer.

-

Riccardo Poli, William B. Langdon, and Nicholas Freitag McPhee. A field guide to genetic programming. Published via http://www.lulu.com and freely available at http://www.gp-field-guide.org.uk. (With contributions by J. R. Koza).*

-

Tina Yu, David Davis, Cem Baydar, and Rajkumar Roy, editors. Evolutionary Computation in Practice. Springer.*

2007

-

Markus Brameier and Wolfgang Banzhaf. Linear Genetic Programming. Springer.*

2006

-

Daniel Ashlock. Evolutionary Computation for Modeling and Optimization. Springer.

-

Anthony Brabazon and Michael O’Neill. Biologically Inspired Algorithms for Financial Modelling. Springer.*

-

Nikolay Nikolaev and Hitoshi Iba. Adaptive Learning of Polynomial Networks Genetic Programming, Backpropagation and Bayesian Methods. Springer.*

2005

-

Enrique Alba. Parallel Metaheuristics: A New Class of Algorithms. John Wiley & Sons.

-

Bir Bhanu, Yingqiang Lin, and Krzysztof Krawiec. Evolutionary Synthesis of Pattern Recognition Systems. Springer.

2004

-

Peer Kleinau. Application of Genetic Programming to Finance and Operations Management. Logos, Berlin.

-

Lee Spector. Automatic Quantum Computer Programming: A Genetic Programming Approach, Springer.*

2003

-

George S. Cowan and Robert G. Reynolds. Acquisition of Software Engineering Knowledge SWEEP. World Scientific, Singapore.

-

A. E. Eiben and J. E. Smith. Introduction to Evolutionary Computing. Springer.

-

John R. Koza, Martin A. Keane, Matthew J. Streeter, William Mydlowec, Jessen Yu, and Guido Lanza. Genetic Programming IV: Routine Human-Competitive Machine Intelligence. Springer.*

-

Michael O’Neill and Conor Ryan. Grammatical Evolution: Evolutionary Automatic Programming in a Arbitrary Language. Springer.*

2002

-

Shu-Heng Chen, editor. Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming in Computational Finance. Springer.

-

Alex Freitas. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery with Evolutionary Algorithms. Springer.*

-

W. B. Langdon and Riccardo Poli. Foundations of Genetic Programming. Springer.*

2001

-

Christian Jacob. Illustrating Evolutionary Computation with Mathematica. Morgan Kaufmann.*

-

Man Leung Wong and Kwong Sak Leung. Data Mining Using Grammar Based Genetic Programming and Applications. Springer.*

-

John R. Koza, David Andre, Forrest H Bennett III, and Martin Keane. Genetic Programming 3: Darwinian Invention and Problem Solving. Morgan Kaufman.*

-

Robert E. Marmelstein. Evolving Compact Decision Rule Sets. Storming Media, USA, 1999.

-

Conor Ryan. Automatic Re-engineering of Software Using Genetic Programming. Springer.*

-

Lee Spector, W. B. Langdon, Una-May O’Reilly, and Peter J. Angeline, editors. Advances in Genetic Programming 3. MIT Press.*

1998

-

Wolfgang Banzhaf, Peter Nordin, Robert E. Keller, and Frank D. Francone. Genetic Programming – An Introduction. Morgan Kaufmann.*

-

William B. Langdon. Genetic Programming and Data Structures. Springer.*

1997

-

Dimitris C. Dracopoulos. Evolutionary Learning Algorithms for Neural Adaptive Control. Perspectives in Neural Computing. Springer.

-

Stan Openshaw and Christine Openshaw. Artificial Intelligence in Geography. John Wiley & Sons.

1996

-

Peter J. Angeline and K. E. Kinnear, Jr., editors. Advances in Genetic Programming 2. MIT Press.*

-

Vladan Babovic. Emergence, evolution, intelligence; Hydroinformatics - A study of distributed and decentralised computing using intelligent agents. A.A. Balkema Publishers, Rotterdam, Holland.

-

Andreas Geyer-Schulz. Fuzzy Rule-Based Expert Systems and Genetic Machine Learning. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg, 2nd revised edition.

1994

-

John R. Koza. Genetic Programming II: Automatic Discovery of Reusable Programs. MIT Press.

-

Kenneth E. Kinnear, Jr., editor. Advances in Genetic Programming. MIT Press.*

1992

-

John R. Koza. Genetic Programming: On the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection. MIT Press.

1986

-

Richard Forsyth and Roy Rada. Machine Learning applications in Expert Systems and Information Retrieval. Ellis Horwood, Chichester, UK.

-

Forsyth’s Machine Learning contains chapters describing his Beagle system, perhaps the earliest example of artificial evolution of program trees. His trees are used to classify data, some of which now feature as UCI benchmarks.

-

In Evolvable Machines and related areas there are quite a few books:

2009

-

Natalio Krasnogor, Steve Gustafson, David A. Pelta and Jose L. Verdegay, Editors. Systems Self-Assembly. Elsevier.*

-

Melanie Mitchell. Complexity a Guided Tour. OUP.*

2008

-

Dario Floreano and Claudio Mattiussi. Bio-Inspired Artificial Intelligence Theories, Methods, and Technologies. MIT press.

-

Philip Husbands, Owen Holland and Michael Wheeler, editors. The Mechanical Mind in History. MIT Press.*

2007

-

Garrison W. Greenwood and Andrew M. Tyrrell. Introduction to Evolvable Hardware: A Practical Guide for Designing Self-Adaptive Systems. Elsevier.*

-

Russell C. Eberhart and Yuhui Shi. Computational Intelligence: Concepts to Implementations. Morgan Kaufmann.*

-

Maja J. Mataric. The Robotics Primer. MIT Press.*

2006

-

Tetsuya Higuchi, Yong Liu and Xin Yao, editors. Evolvable Hardware. Springer.*

-

Richard A. Watson. Compositional evolution: the impact of sex, symbiosis and modularity on the gradualist framework of evolution. MIT Press.*

-

Kenneth A. De Jong. Evolutionary computation: a unified approach. MIT Press.*

-

Andries P. Engelbrecht. Fundamentals of computational swarm intelligence. John Wiley & Sons.*

2005

-

Andreas Deutsch and Sabine Dormann, Cellular Automaton Modeling of Biological Pattern Formation: Characterization, Applications, and Analysis. Springer.*

-

Martyn Amos. Theoretical and Experimental DNA Computation. Springer.*

-

Edward Keedwell and Ajit Narayanan. Intelligent Bioinformatics: the Application of Artificial Intelligence Techniques to Bioinformatics Problems. John Wiley & Sons.*

2004

-

Lukas Sekanina. Evolvable Components: From Theory to Hardware Implementations. Springer.*

-

Marco Dorigo and Thomas Stützle. Ant Colony Optimization. MIT press.*

2003

-

Tanya Sienko, Andrew Adamatzky, Nicholas G. Rambidi and Michael Conrad, editors. Molecular Computing. MIT Press.*

-

Sanjeev Kumar and Peter J. Bentley, editors. On Growth, Form and Computers. Elsevier.*

-

Gary Fogel and David Corne. Evolutionary Computation in Bioinformatics. Morgan Kaufmann.*

2002

-

David E. Goldberg. The Design of Innovation. Springer.*

-

Alex A. Freitas. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery with Evolutionary Algorithms Springer.*

-

David B. Fogel. Blondie24: Playing at the Edge of AI. Morgan Kaufmann.*

-

Moshe Sipper. Machine Nature: The Coming Age of Bio-Inspired Computing. McGraw-Hill.

2001

-

Ricardo Salem Zebulum, Marco Aurelio C. Pacheco and Marley Maria B. R. Vellasco. Evolutionary Electronics: Automatic Design of Electronic Circuits and Systems by Genetic Algorithms. CRC.*

-

James Kennedy and Russell C. Eberhart, with Yuhui Shi. Swarm Intelligence. Morgan Kaufmann.*

2000

-

Stefano Nolfi and Dario Floreano. Evolutionary Robotics: The Biology, Intelligence, and Technology of Self-Organizing Machines, MIT Press.*

-

Julian Brown. The Quest for the Quantum Computer. Touchstone, New York.*

1999

-

Peter J. Bentley, editor. Evolutionary Design by Computers. Morgan Kaufmann.*

1998

-

Daniel Mange and Marco Tomassini, editors. Bio-Inspired Computing Machines. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes, Switzerland.*

-

Marco Dorigo and Marco Colombetti. Robot Shaping: An Experiment in Behaviour Engineering. MIT Press.

-

Adrian Thompson. Hardware Evolution. Automatic Design of Electronic Circuits in Reconfigurable Hardware by Artificial Evolution. Springer.* Unfortunately Thompson’s prize winning book is now out of print.

1997

-

Moshe Sipper. Evolution of Parallel Cellular Machines: The Cellular Programming Approach. LNCS 1194, Springer.

1996

-

Eduardo Sanchez and Marco Tomassini, editors. Towards Evolvable Hardware: The Evolutionary Engineering Approach. LNCS 1062, Springer. This is based on the 1995 Lausanne workshop on evolvable hardware but also includes introductory material.

3 Proceedings

The EuroGP conference continues to be the annual event for genetic programming. All the papers, even from the first event in 1998, are available online. In 1999, when the journal started, both GECCO and CEC conference series also started. They both continue to publish many GP and evolvable hardware papers. Since 2003 the Ann Arbor Genetic Programming Theory and Practice workshop has also become an annual event.

In the evolvable machines arena, since the 1995 Lausanne workshop (mentioned above) ICES has met approximately every 2 years. Meanwhile the annual NASA-DoD workshop on evolvable hardware (starting as EH-1999) has become an annual fixture. Since 2006 it has also been sponsored by the European Space Agency and renamed Adaptive Hardware and Systems, taking in many areas of sophisticated electronics as well as evolvable hardware.

Other evolutionary computation conferences also accept GP/EM papers or even have GP/EM tracks. Examples include PPSN, WSC (internet), Artificial Evolution (France), ALife, ICANNGA, FOGA, IJCNN, ICMLA, ICPR, SEAL, FLAIRS and CIRAS.

4 Publication summary

Most of the GP statistics are derived from the GP-bibliography.Footnote 1 The bibliography is available from the Internet in a variety of formats and locations. Also entries from it have been incorporated in other online bibliographic resources. Unfortunately, no similar effort has been undertaken for the literature on evolvable hardware, so this section deals only with GP.

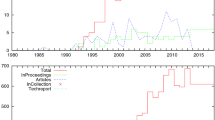

As of November 2009 there were 5253 GP entries in the GP bibliography (excluding late breaking papers, unpublished, miscellaneous, master thesis, undergraduate student reports and some short posters). (5253 is nearly twice the number in 2004.) Figure 1 shows the number of each entry according to when they where published and by type. Naturally most papers were published in conference proceedings. Initially there was an exponential rise, with the number of publications doubling every year from 1988 to 1996. This has been followed by a rapid linear increase since 1997. (Figure 2 right shows that this is a typical behaviour for Computer Science bibliographies.) In the case of GP (and perhaps others) the effort available to maintain the bibliography has not increased exponentially. Hence the bibliography has lagged behind the growth in the field. A lot of effort was devoted to ensuring the GP bibliography was as complete as possible up to 1996 (corresponding to the publication of Advances in Genetic Programming volume 2 which contains an annotated bibliography of GP [3]). Unfortunately since then there have been GP publications which have escaped recording in the bibliography. This leads to a bias in favour of those researchers who actively support the maintenance of the bibliography.

Left: Number of authors and co-authors of genetic programming entries in the gp-bibliography (1980–November 2009). We exclude late breaking papers, unpublished, misc, masters thesis, undergraduate students and some short posters. The lower curves plots the number of authors who had not previously published in GP. The GP distribution of publication dates is somewhat typical of computer science bibliographies (November 2009, right). Note change of scales

Figure 2 plots the number of people active in GP (i.e. according to the GP bibliography they published in a given year). Figure 2 shows that even in recent years (2000 onwards) almost half the authors who published in that year were new to GP. The total number of people who have published GP related papers is about 3494. (Almost twice the figure in 2004.) The number of new authors per year, along with the rise and fall of publication types like PhD dissertations, gives a sense of how vibrant the GP community is. However, as GP has matured more application papers appear in biology, chemistry and other non-computer science journals. Unfortunately this probably means some recent articles are missing.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the number of authors per GP publication (excluding MSc. theses, unpublished, etc.) for each year. We can see that as the field took off in the 1990s, the publications were dominated by one and two authors. However, as we approach the 2000s, the number of three, four and five authors has been steadily increasing. As GP is largely an empirical research field, it makes sense that as applications and analysis has matured, more collaboration is taking place resulting in multiple authors. Also, as GP is applied to other disciplines, we would expect to see more co-authors appear on publications.

4.1 Use of the GP bibliography

The GP bibliography can be searched via the collection of computer science bibliographies. The Artificial Intelligence collection of bibliographies is the 4th largest computer science collection by subject. And within the AI collection, the GP bibliography is the 4th largest. (Up from 7th in 2004.) Since logging started (April 2003) up to November 2009 there have been approximately 23,251 page views of the GP bibliography home page. Figure 4 shows that typically the use of the bibliography web pages is concentrated in Europe, North and South America, the far east and India.

A typical pattern of global users of the GP bibliography web pages (green and blue dots). Europe, USA, China, Hong Kong, Korea, India, Canada, Brazil and Chile. The red dot is the location of the host http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk

Online electronic versions of papers, even those on publisher web pages, can be directly linked to the bibliography. There are 4115 GP publications with such links (almost three times that in 2004). In almost all cases, possibly with a small amount of manual intervention, the paper is actually available via its links. This is an increase on 2004, when about 10% of links were broken. In other words the text of 76% of GP papers are immediately available via hyperlinks in the bibliography. This is 25% more than 5 years ago. Most of the change comes from the increased proportion of journal articles (92 vs. 54%), conference proceedings (73% up from 45%) and papers in collections (46% up from 32%) which are available online. The fraction of PhD theses (69 vs. 63%) and technical reports (87 vs. 82%) are little changed. This is a little disappointing. For one of your papers to have an impact it must be available and that means available on the web [4]. Yet still about a quarter of GP papers are not (as far as the main index is concerned) on line.

4.2 Use of the GP bibliography papers

Figure 5 shows that most requests to download GP papers are automatically generated by computers interrogating other computers. However, since many robots are written to try and conceal their owners and their purposes, it is impossible to be sure that web traffic is correctly allocated. The two main robots are those (apparently) belonging to Google and Yahoo. Much of the load is due to robots re-reading the papers (to check that they have not changed). Some bursts of activity, cf. Figure 6, appear to be concentrated at weekend nights to avoid inconveniencing other users. However robot activity varies radically. Figure 7 suggests a vaguely log-normal distribution, with download rates clustering near the average.

GP paper downloads per hour (17 November 2008–17 November 2009). Note log scales. User activity ■ msnbot □ and Google bot × follow approximate power laws (x −3 and x −1) The total + is more parabolic suggesting a log-normal distribution. Yahoo * has a similar shape, hinting it is also the combination of a few underlying power laws. All distributions are much wider than would be expected if downloads were random independent events. Notice there are only 17 hours in the year with no activity (perhaps due to server outage)

The bibliography is used continuously, at every hour of every day (including Christmas). There are no downloads recorded for 17 hours, indicating that the web site was probably down for only 17 hours in the whole year.

It appears that on average more than 20 GP papers are downloaded via the bibliography per day by people.

Over the past 3 years, the most popular papers (i.e. the most downloaded by people) have been tutorials on GP, followed by financial applications. Cf. Table 1. (More than half the top 20 downloaded papers are on finance.) This is followed by surveys, user manuals for GP packages and more widely drawn applications. Naturally the most downloaded authors are those with the most online papers linked to the bibliography and authors of popular tutorials or popular finance papers, cf. Table 2.

When calculating Tables 1 and 2 we have been as scrupulous as possible to ensure we include only real personal downloads and exclude all web robots. Unfortunately this is not easy and so we have deliberately erred on the cautious side. By excluding cases where we are not sure, we will underestimate. Nonetheless the results should still give a fair indication of use of the GP bibliography by people.

Surprisingly GP papers downloaded by people via the bibliography are mostly accessed using commercial Internet service providers (ISPs). Even the most active university (Essex) is not in the top ten. This could be because universities may have subscriptions which encourage academics to search via publishers’ web pages or simply because most people access the Internet via ISPs. Even university students who work from home or coffee shops, etc., may use an ISP rather than a university connection.

4.3 The GP coauthorship community

In 2006 Cotta and Merelo [25] used bibliographic data from DBLP [26] relating to many fields of evolutionary computation, including GP and Evolvable Hardware, to show the global structure of EC. Future reviews of genetic programming and evolvable machines might also use other literature analysis tools such as those recently used on Swarm Intelligence [27].

The GP bibliograpy has been used in a number of studies. For example, Luthi investigated research collaborations in GP using co-authorship [28] and how friendships change with time [29]. In [30] we showed how the “small world” sparse connections of the central connected component of the GP co-authorship graph can be analysed into eigen-collaborations.

As a result of this research, the bibliography now includes an online tool which displays the current collaboration network and allows users of web browsers to search and navigate through collaborations. It even allows direct access to the papers produced as fruits of such joint work. Figure 8 shows the central connected component of the GP bibliography.

Each of the 1597 red dots represents an author of one or more GP entries in the genetic programming bibliography who is connected by being listed as a joint author with one or more entries with another person in the graph and so eventually is linked by co-authorship to R. Poli. Lines connect coauthors. (To reduce clutter only links to first author are shown.) The area of each dot indicates the number of entries. This graph contains 3358 entries of the total of 6086. The interactive display uses the cursor to label nodes, allows dynamic searches, exploring links and direct access to the fruits of this joint work

5 Internet

The GP community has always made extensive use of the Internet. For example with the early establishment (in 1992) of the GP mailing list. (Now to be found at http://www.genetic_programming@yahoogroups.com). However the GP ftp archive, FAQ and the GP notebook have not been maintained and there is no wiki dedicated to GP. (Old papers and code can be found at ftp://cs.ucl.ac.uk/genetic/ftp.io.com/). Instead they have been supplanted by the use of individual home pages. This means material is scattered across the world wide web. However, while by no means as comprehensive as the biological literature, Google (and Google Scholar), CiteSeerX, the arXiv e-Print archive and various computer science bibliographies, do give rapid access to a large numbers of GP/EM papers. The evolvable machines community has never felt the need for centralised ftp servers and perhaps wisely jumped directly to using distributed world wide web pages.

Back in November 1997 Altavista listed more than 76 different sites directly related to GP (excluding personal home pages). By September 1999 there were approximately 310 personal home pages written by people interested in GP or evolvable machines. Five years later (Nov 2004) this has risen to about 870 and now has reached about 1400 (see http://www.cs.ucl.ac.uk/staff/W.Langdon/homepages.html for GP pages).

6 Freeware

There is a wealth of freely available software [31]*. Perhaps unsurprisingly commercial products tend to figure little in academic journals. (See [32]* for a counter example.) Source Forge alone lists 63 GP projects. This may be why most researchers continue to use either home grown software or public domain software provided by other researchers. For example Zongker’s lil-gp Footnote 2 [33]* has proved popular, with updated versions available both from Michigan State University and Sean Luke.Footnote 3 There are many C++ implementations, e.g. EODEV Footnote 4 and Gagne’s open Beagle Footnote 5 (not to be confused with Forsyth’s Pascal Beagle). While Java implementations include Sean Luke’s ECJ.Footnote 6 TinyGP is available in both C and Java.Footnote 7 Other implementations, include Koza’s Lisp code Footnote 8 and implementations in SmallTalk, Mathematica, Prolog, Matlab Footnote 9 (e.g. GPLAB Footnote 10), Perl Footnote 11 and Python.

There are also several non standard GP systems available. These include Spector’s PushGP Footnote 12, O’Neill and Ryan’s Grammatical Evolution Footnote 13 and Olsson’s ADATE.Footnote 14

7 Summary

The journal continues to reflect the expansion of the most exciting field in evolutionary computation. As part of this, we continue to publish reviews of interesting and relevant resources. The reviews are summerised in Sect. 1. For practical reasons (also given in Sect. 1) we have concentrated on books. This trend will probably continue but with the continued inclusion of books from related areas as well as genetic programming and evolvable machines.

Sections 2 and 3 have described the major components of the GP/EM literature, whilst Sect. 4 described in detail the evolution and use of the GP bibliography. Finally our community’s heavy use of the Internet (Sect. 5) and tools available from it (Sect. 6) have been reviewed.

Notes

The GP bibliography http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/~wbl/biblio/ was started from John Koza’s bibliography (published in Genetic Programming II [34]). Over the years I have been greatly assisted in the maintenance and expansion of the GP bibliography by the subscribers to the genetic-programming electronic mailing list

See also Adam Hewgill’s Brock Strongly Typed lil-gp

EO C++ templates-based evolutionary computation library http://www.eodev.sourceforge.net/

Gagne’s open Beagle C++ http://www.beagle.gel.ulaval.ca/

Sean Luke’s ECJ (Java) http://www.cs.gmu.edu/~eclab/projects/ecj/

Poli’s Tiny GP can be found via his page http://www.cswww.essex.ac.uk/staff/rpoli/TinyGP/

Koza’s original Lisp http://www.genetic-programming.org/gplittlelisp.html

Old implementations in C, C++, Matlab, SmallTalk, Mathematica and Prolog ftp://cs.ucl.ac.uk/genetic/ftp.io.com/

Silva’s GPLAB GP tool box for MATLAB http://www.gplab.sourceforge.net/

Bob MacCallum’s PerlGP http://www.perlgp.org/

PushGP (Lisp) http://www.hampshire.edu/lspector/push.html

Grammatical Evolution http://www.grammatical-evolution.org

References

W.B. Langdon, Genetic programming and evolvable machines: books and other resources. Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 1(1/2),165–169 (2000)

W.B. Langdon, S. Gustafson, Genetic programming and evolvable machines: five years of reviews. Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 6(2), 221–228 (2005)

W.B. Langdon, A bibliography for genetic programming, in Advances in Genetic Programming 2, appendix B, ed. by P.J. Angeline, K.E. Kinnear Jr., (MIT Press, 1996), pp. 507–532

S. Lawrence, Free online availability substantially increases a paper’s impact. Nature 411(6837), 521 (2001)

J.R. Koza, R. Poli, A genetic programming tutorial (2003)

M.A.H. Dempster, V. Leemans, An automated FX trading system using adaptive reinforcement learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 30(3), 543–552 (2006). Special Issue on Financial Engineering

Jin Li, Zhu Shi, Xiaoli Li, Genetic programming with wavelet-based indicators for financial forecasting. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 28(3), 285–297 (2006)

R.G. Bates, M.A.H. Dempster, Y.S. Romahi, Evolutionary reinforcement learning in FX order book and order flow analysis, in IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Financial Engineering, Hong Kong, 20–23 March 2003, pp. 355–362

W.B. Langdon, W. Banzhaf, A SIMD interpreter for genetic programming on GPU graphics cards, in Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Genetic Programming, EuroGP 2008, vol 4971, ed. by M. O’Neill et al., of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Naples, 26–28 March 2008 (Springer), pp. 73–85

M.A.H. Dempster, Y.S. Romahi, Intraday FX trading: an evolutionary reinforcement learning approach, in Proceedings of Third International Conference on Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning - IDEAL 2002, vol 2412, ed. by H. Yin et al., of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Manchester, 12–14 August 2002 (Springer), pp. 347–358

M.A.H. Dempster, T.W. Payne, Y. Romahi, G.W.P. Thompson, Computational learning techniques for intraday FX trading using popular technical indicators. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 12(4), 744–754 (2001)

M.A. Kaboudan, Genetic programming software to forecast time series, in Computing in Economics and Finance, University of Washington, Seattle, USA, 11–13 July 2003

R. Forsyth, BEAGLE A Darwinian approach to pattern recognition, Kybernetes 10(3), 159–166 (1981)

J.R. Koza, Survey of genetic algorithms and genetic programming, in Proceedings of 1995 WESCON Conference IEEE (1995), pp. 589–594

M A.H. Dempster, C.M. Jones, The profitability of intra-day FX trading using technical indicators. Working Paper 35/00, Judge Institute of Management Studies, University of Cambridge (2000)

D. Zongker, B. Punch, lilgp 1.01 user’s manual. Technical report, Michigan State University, USA, 26 March 1996

M.P. Austin, G. Bates, M.A.H. Dempster, V. Leemans, S.N. Williams, Adaptive systems for foreign exchange trading, Quant. Finance 4(4), 37–45 (2004)

M. Austin, G. Bates, M. Dempster, S. Williams, Adaptive systems for foreign exchange trading, Eclectic 18, 21–26, Autumn (2004)

M.A.H. Dempster, C.M. Jones, A real-time adaptive trading system using genetic programming, Quant. Finance 1, 397–413 (2000)

L. Wagman, Stock portfolio evaluation: an application of genetic-programming-based technical analysis, in Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming at Stanford 2003, ed. by J.R. Koza, Stanford Bookstore, Stanford, CA, 94305-3079 USA, 4 December 2003, pp. 213–220

J.C. Werner, M.E. Aydin, T.C. Fogarty, Evolving genetic algorithm for job shop scheduling problems. Technical report, School of Computing, Information Systems and Mathematics, London South Bank University, UK (2001)

P.K. Spivak, Discovery of optical character recognition algorithms using genetic programming, in Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming at Stanford 2002, ed. by J.R. Koza, Stanford Bookstore, Stanford, CA, 94305-3079 USA, June 2002, pp. 223–232

Justine W. Shen, Solving the graph coloring problem using genetic programming, in Genetic Algorithms and Genetic Programming at Stanford 2003, ed. by J.R. Koza, Stanford Bookstore, Stanford, CA, 94305-3079 USA, 4 December 2003, pp. 187–196

J.-F. Dupuis, M. Parizeau, Evolving a vision-based line-following robot controller, in The 3rd Canadian Conference on Computer and Robot Vision (CRV’06), IEEE Computer Society (2006), p. 75

C. Cotta, J.-J. Merelo, Where is evolutionary computation going? A temporal analysis of the EC community, Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 8(3), 239–253 (2007)

M. Ley, DBLP—some lessons learned, Proc. VLDB Endowment 2(2), 1493–1500 (2009)

R. Poli, Analysis of the publications on the applications of particle swarm optimisation, J. Artif. Evol. Appl. (2008)

M. Tomassini, L. Luthi, M. Giacobini, W. B. Langdon, The structure of the genetic programming collaboration network, Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 8(1), 97–103 (2007)

M. Tomassini, L. Luthi, Empirical analysis of the evolution of a scientific collaboration network, Phys. A 385, 750–764 (2007)

W.B. Langdon, R. Poli, W. Banzhaf, An eigen analysis of the GP community. Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 9(3), 171–182 (2008)

B. Dolin, J.J. Merelo, Resource review: a web-based tour of genetic programming, Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 3(3), 311–313 (2002)

J.A. Foster, Review: discipulus: a commercial genetic programming system, Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 2(2), 201–203 (2001)

G.C. Wilson, A. McIntyre, M.I. Heywood, Resource review: three open source systems for evolving programs–lilgp, ECJ and grammatical evolution, Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 5(1), 103–105 (2004)

J.R. Koza, in Genetic Programming II: Automatic Discovery of Reusable Programs (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1994)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Paul Ortyl, Julian F. Miller and Michael O’Neill.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Langdon, W.B., Gustafson, S.M. Genetic Programming and Evolvable Machines: ten years of reviews. Genet Program Evolvable Mach 11, 321–338 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10710-010-9111-4

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10710-010-9111-4