Abstract

Commercial and public sector interests surrounding technological developments are promoting a widespread transition to autonomous vehicles, intelligent transportation systems and smart phone communications in everyday life, as part of the smart mobility agenda. There is, however, inadequate understanding about the impact of such a shift on potential users, their readiness to engage and their vision of transportation systems for the future. This paper presents the findings from a series of citizen panels, as part of a 2-year project based in south-west England, focusing on in-depth discussions regarding the future of commuting, the flow of the daily commute and the inclusion of publics in smart mobility planning. The paper makes three key propositions for researchers: enabling publics should lead to a visionary evolution in the development of sustainable transportation systems; commercial interests, public bodies and IT innovators must employ a holistic approach to mobility flows; and, processes engaging publics need to be inclusive when co-creating solutions in the transition to smart mobilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Commercial and public sector interests, underpinned by the ascendance of big data (Kitchin, 2014), are pushing forward the transition to smart mobility systems. This transition focuses on the introduction of autonomous vehicles, intelligent transportation systems, smart phone software and communications (Carvalho, 2015) and approaches such as the Mobility-as-a-Service app, providing an on-demand service integrating all transport options (Pangbourne, 2017). The evolution of big data has provided opportunities for the commercial sector to explore social and cultural real-time patterns (Janowicz, 2012) and implicit temporal and spatial concerns, in areas such as traffic management (Barrero et al., 2010), wireless networks/GPS (e.g. Ding et al., 2010), travel time systems (e.g. Haghani et al., 2010) and bike-sharing schemes (e.g. Cichosz, 2013). Some academics are predicting that the evolution of big data will bring about a methodological revolution (Bartscherer & Coover, 2011; Berry, 2012; Gupta et al., 2012), with Hey et al. (2009) referring to it as the ‘fourth paradigm’ based on data intensive inquiries and statistical exploration across the sciences. Those working in the public sector view such technologies as palatable mechanisms to smooth the transition and avoid radical system changes; commercial interests, however, can be perceived as focusing on this as a marketable, short-term opportunity rather than a more long-term change that has engaging publics and societal inclusiveness at its core.

One way in which this transition has manifest in Transport research is the rapid increase in the studies about human mobilities, and the vast collection of large datasets (Chen et al., 2016). The ability to combine data from new technologies, sensors and software with other sources and using non-traditional techniques to store, manage and visualise them (Chen et al., 2012; Graham & Shelton, 2013) suggests, in many respects, that technology has no bounds and its potential is limitless. This vast reality has already made an impact via the ways in which individuals use mobile devices to make more efficient and rapid, real-time travel decisions, as the desire for “one click solutions” to optimise their journeys increases. These impacts include improvements to waiting times and access to public services (Papangelis et al., 2016), switching routes when informed about delays (Mak et al., 2015) and about changes to the weather (Liu et al., 2015). Such ascendance has helped meet the aspirations of organisations, the business and IT sectors and policy makers alike (Regalado, 2014). The perception, however, that big data will enable us to overcome the challenge of effecting meaningful and sustained behavioural changes may be misguided as data analytics has magnified the temporal mismatch between the ‘go to market’ commercial approach and academic research and practice.

As partnerships develop between technology providers, big data analysts and local authorities (Goodall et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018; Freudendal-Petersen et al., 2019), our attention must turn to the processes of engagement with publics. The smart city concept is defined by rational, passive individuals undertaking required behavioural changes (Barr et al., 2021). Their mobilities generate datasets that are used to inform and underpin changes to service provision, improvements to operational efficiency and solutions to current transport problems. This consumer-centric, demand driven approach (Bogers et al., 2016; Cecere, 2014) can only collect a superficial level of data regarding decision-making and is limited in its capacity to be proactive in changing established patterns and reshaping them in contexts specific to the user. The technologically focused IT revolution does not cater for an understanding of nuances and intricacies of individual commuter journeys; for example, the why and when individuals make decisions about how they travel or what the key factors affecting those decisions are. Even though a shift away from passive participants having to accept services as they are, with little opportunity for comment, has begun (Anderson et al., 2010), a fully inclusive and timely engagement process to shape policy prior to implementation is still lacking.

This paper seeks to use qualitative insights from people’s experiences from their daily mobilities. It aims to generate critical reflection and dialogue regarding three propositions for researchers: engaging publics should lead to a visionary evolution in the development of sustainable transportation systems; commercial interests, public bodies and IT innovators must employ a holistic approach to mobility flows; and, processes engaging publics need to be inclusive when co-creating solutions in the transition to smart mobilities. The paper is structured in the following way. Next, we discuss the limitations of the smart mobility paradigm, the need to extend planning and design processes for greater user inclusivity and the use of co-creation research to integrate publics fully in visions for the future. Then, the methods and empirical data from a series of five citizen panels, as part of a two-year sustainable transport project in south-west England, are detailed as one example to illustrate the three propositions. The paper ends by providing an alternative view of smart mobility and the ways in which academics and publics can explore. The likely impacts of new technologies of mobility.

Smart mobilities: technology, engagement and visioning urban futures

Contesting the smart mobility paradigm

To date, no one definition effectively encapsulates the smart mobility paradigm and its relationship with smart cities; even though, smart mobilities is one of the defining features of such urban spaces (Chourabi et al., 2012). The term smart, or intelligent, mobility appeared at the beginning of the Nineties, referring to urban mobility systems that were becoming increasingly techno-centric with innovation informing decision-making and practices to connect people, places and merchandise across transport networks (Albino et al., 2015). From an IT perspective, its main aim is the interconnection of mobile devices, sensors and actuators to improve the capability for forecasting to support the optimization of traffic fluxes and manage urban flows (Barceló, 2015). Intelligent transportation systems (ITS), for example, have revolutionised mobility in the last 30 years, with the most recent progress worldwide in America, Europe, Japan and Australia (e.g. Jahangiri & Rakha, 2015; Kostakos et al., 2013; Sassi & Zambonelli, 2014). Instead, Benevolo et al. (2016) proposed an action taxonomy that starts with smart actions, followed by governance and then the introduction of ITS, with IT innovation supporting the optimization of traffic fluxes and collecting opinions about urban living and public transport service quality. Papa and Lauwers (2015) argue that smart mobility must be integral to the smart cities concept, rather than stand alone, and the need for local context, citizen inclusion and interrelation between physical and digital, based on the British Standard Institution (BSI, 2014) definition of smart city. The 2016 UN Report stated that the ideal aims for smart mobility are that it needs to be safe, accessible, affordable and sustainable (Singh, 2016). Hence, we must either align the different definitions into an all-inclusive definition or, more likely, be better at appreciating the values and perspectives held by others.

The smart mobility paradigm appears, in essence, to be limited and lacking a visionary evolution. Conventional mobility planning was based on the premise that travel time was a cost that should be as short as possible (Banister, 2008) and this latest paradigm does not seem much different in its overarching concept. Batty et al. (2012) and Hemment and Townsend (2013) claim that the smart mobility agenda does consider the needs of people and communities alongside the IT diffusion; yet Barr et al. (2021) argue that many smart city programmes focus on only improving existing patterns of mobility with techno-centric innovation. Others, such as Bélissent (2010) and Schaffers et al. (2011), add that proposed solutions around the smart mobility debate are predominantly exclusive of people-centric initiatives by local Councils and authorities. Interestingly, the sustainability and place-making mobility paradigms put accessibility as the key driver, rather than speed, convenience and cost, incorporating people under the umbrella of social, environmental and climate impacts in the former (Banister, 2008; Litman, 1998), and pivotal in local contexts and the development of quality urban living in the latter (Cervero, 2009; Gehl, 2013; Jones & Evans, 2012). In the smart mobility example, however, people are constructed as consumers of mobility products such as Mobility-as-a-Service, as part of a digital optimisation of existing infrastructure, services and mobility practices (Lauwers & Papa, 2014; Paiva et al., 2021). Hence, despite the development of multiple mobility paradigms and the different approaches in current urban planning literature, the car-dominated techno-centric theme has remained.

Framing commercial and technological innovation within existing practices and behaviours is based on a ‘one size fits all’ approach (Jasanoff, 2004; Perrons & McAuley, 2015; Schuetze, 2010). This approach is likely to capture only part of the narrative and is not able to depict personalised information such as why people behave the way they do. Companies have been increasingly aware of the need to change the way they perceive their customers, from being passive recipients of their products to active participants in a two-way interaction regarding product development (Lundkvist & Yakhlef, 2004). Starbucks, PepsiCo and Walkers, for example, engage consumers in processes to develop new brand ideas, services and flavours (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004). Such data collection methods are, however, at risk of having a wide variance in quality of user-generated content (Agichtein et al., 2008) and are time intensive in collation and analysis. Thus, Kim and Slotegraaf (2016) proposed a dynamic exchange approach that generates the most pertinent ideas via learning about consumer needs and educating them of company brand interests and strategies. Although this is an evident shift towards involving publics in consumer and lifestyle choices, the approach remains narrow and limited in its capacity to create spaces whereby publics can inject the nuances and intricacies of local places in a fully inclusive manner. Thus, we next discuss the need to extend planning and design processes for greater user inclusivity.

Mobilising user inclusivity

Demand is increasing for quality transport service provision and accessibility for all. The primary purpose of smart mobilities, perceived as the solution by many, is to provide a seamless, door-to-door service for all citizens, whilst minimising the environmental impact (Benevolo et al., 2016; Paiva et al., 2021). Planning and modifications have typically been via a top-down expert led approach focusing on mobilities and traffic flows (Boisjoly & Yengoh, 2017), in terms of volume, diversity of service users and quality of the public and active transport infrastructure (Clark & Curl, 2016; Nickpour & Jordan, 2013). Physical issues of accessibility, reliability, safety, usability and quality of service are key indicators commonly considered in the design, with energy concentrated on addressing the conflicting desires and agendas of key stakeholders (Kammerlander et al., 2015; Steinfeld, 2013). Currently, other considerations, such has the psychosocial aspects of using personal mobilities (e.g. financial, emotional, ideological; individual attributes) continue to be overlooked; so, for example, endeavouring to ensure the journeys are inviting and enjoyable (Nickpour & Jordan, 2013; Lim et al., 2016; Chatterjee et al., 2017).

Current developments are underpinned by real-time data collection and analysis, multi-modal patterns of mass movement and digital technologies (Ribeiro et al., 2021). Alongside this, is the continuing misconception that big data and artificial intelligence together, will enable services to be made available to all citizens, improving their daily lives markedly (Paiva et al., 2021). This flawed approach requires society, old and young, rich and poor, mainstream and marginalised, to be engaged and knowledgeable, if not proficient, across multi-technological devices and platforms. The younger generations, for example, were born into this world and adapt to use new technologies at pace and with enthusiasm (Ilie et al., 2020). Conversely, older colleagues, friends and family, along with poorer and handicapped citizens (Kammerlander, et al., 2015) are often left behind compounded by a lack of technical and operational know-how (Zhang et al., 2020). Linear demarcations, such as age and affluence, reinforce the big-data-led societal categorisations and the planning of more inclusive smart mobility systems can be advanced by considering intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989; Kuster, 2019; Day, 2021). Perceptions of commuter journey time, for example, when studied from an intersectoral viewpoint, can be considered alongside well-being, environmental concern and/or perceptions of public transport services in understanding commuting decisions and informing the planning process.

There are signs of a recent shift towards introducing a co-creative process empowering publics participation (Bell et al., 2021; Nared, 2020) and understanding the needs, values and insights of transportation users and non-users alike, to build sustainable and inclusive capability (Majumdar, 2017). Once citizens feel their needs have been heard and integrated, they have adequate digital literacy, and are trusting of the process, it is likely they will participate as willing data providers and end-users and even promote the value of smart technologies (Ribeiro et al., 2021). With rapid changes to inclusivity and accessibility in the transport sector, researchers and designers need to appreciate and understand the way in which people engage and interact with transport. They need to understand how older, marginalised and vulnerable users experience the services and systems, and how to generate confidence to try new ways of finding information and accessing products. The concept of smart mobility goes far beyond tangible problem-solving, as the expectation of future contributions embroil truly innovative solutions (Gouveia et al., 2016). The key to realising that expectation, is enabling the users to explore, share and communicate their fears, (mis)perceptions and experiences via ‘blue skies’ thinking and visions of future societies. Hence, we next discuss the use of co-creation research to integrate publics fully in visions for the future.

Enabling publics to be visionary

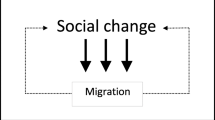

Engaging publics in debates regarding social change and policy is not new (Grand et al., 2015). This has traditionally been a reactive process trying to rebuild public trust after policy failure (Burall & Shahrokh, 2010), with sectors being at different stages regarding the drivers for, and stages of, such engagement (Featherstone et al., 2009). Since the turn of the century, there has been a shift in emphasis towards earlier engagement with publics in an aim to shape policy prior to implementation to reduce the level of dissatisfaction and disengagement (Andersson et al., 2010); well encapsulated in the UK’s National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement definition as ‘a two-way process, involving interacting and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit’ (NCCPE, 2010). Publics who have been part of two-way dialogues commonly feedback how valuable these processes are, assuming they are framed around publics aspirations (Burall & Shahrokh, 2010; cf. Parliamentary report, 2000). There is ongoing debate, however, regarding whether or not the interaction and dialogue when engaging publics is genuinely transparent, mutual and collaborative (Davies et al., 2009; Horst & Michael, 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2012). Universities have been guided to evaluate their public engagement more effectively (Vargiu, 2014), integral to the 2009 directive (RCUK, 2015), and for academics to interact with stakeholders in meaningful ways throughout the whole lifecycle of research projects from conception to dissemination (Holliman et al., 2015; Scanlon, 20142014). Publics have choices regarding how they contribute to, and embrace, societal issues such as smart mobilities and sustainable transport and, researchers need a succinct, timely and unified approach to facilitate those choices and provide a freedom to be visionary on a ‘blue skies’ scale.

The broad interpretation regarding the concept of public engagement (Tlili & Dawson, 2010), and resistance by some, are the foundations of the complexities involved in the transition to fully inclusive public engagement in research. Grand et al. (2015) detail the historic context of public engagement, also termed engaged research, and cite a plethora of examples illustrating the intricacies in defining and implementing such a process. Behavioural change programmes continue to be focused on delivery to publics who are recruited to test the effectiveness of certain interventions (Manika & Golden, 2016). More recent theoretical work, however, promotes a shift from this ‘deficit’ model of engagement to a participation model, whereby building and maintaining relationships with publics is key (Cook & Zurita, 2019). This nuanced approach effects change in behaviour without the prerequisite of information transfer (Broockman & Kalla, 2016) and by empowerment of publics (Chilvers & Kearnes, 2015). Although researchers do recognise the need to involve publics for projects to be collaborative, some do not find it easy (Staley, 2009) and others question the methodologies that are required to ensure academic validation is integrated effectively with meaningful contributions from publics (Holliman, 2015; Holmwood, 2014; McCallie et al., 2009). To understand why people make the choices they do and what the key drivers of those choices are, we need to delve into the place-context and specific issues relevant to everyday individual behaviours and decision-making. This resonates with social science methods such as action research, participatory research and co-creation.

Engaging publics is key to the co-creation process and should lead to a visionary evolution in the development of sustainable transportation systems (e.g., Barr et al., 2010, 2013; Shaw et al., 2014; Buhalis and Foerste, 2015). Co-creation approaches, engaging with individuals and communities as partners rather than experimenting on them (de Leeuw et al., 2012; Koster et al., 2012; Tobias et al., 2013), are driven by open and critical reflection by the participants (Luusua et al., 2015) and tease out the barriers and attitudes towards publics engaging with ‘experts’ (Borén et al., 2017), including diverse groups in transport planning and policy decisions (Rönkkö et al., 2017). This openness to new ideas and empathy triggered by personal experiences broadens the creativity mind-set to effect change by visionary ideas and possibilities (Fredrickson, 1998, 2001). This in-depth qualitative approach is crucial in the ‘smart’ era as it explores the nuances and intricacies in human decision-making and behaviour in contexts to inform the big data analytics. Such people- and place-centred insights provide knowledge that cannot be produced in one place, then replicated and rolled out across the rest of society (Carayannis and Campbell 2009; Schoonmaker and Carayannis 2012). Citizens must not only be encouraged to participate in innovative mobility solutions by becoming digitally included through IT awareness (Rossetti, 2015), but also to engage with co-creation research and be actively involved in designing, producing and trialling interventions. Without co-creation, claims that smart mobility innovations such as autonomous vehicles and Mobility-as-a-Service provide benefits regarding accessibility to previously excluded groups, are debatable (Clark et al., 2016). To maximise the impact of such pathways and generate visionary evolutions in transportation systems relies on the transfer of insights in a timely and inclusive fashion.

This literature shows that there is a need for a clearer, more definitive direction in the transition to smart mobilities and a wider appreciation of the ‘improved flow’ agenda. Engaging publics is generally not perceived as core to this transition and, when it is, remains underutilised in its evolutionary capacity. In the remainder of this paper, we aim to answer the following three questions:

-

(1)

How can public enablement lead to a visionary evolution in transportation systems?

-

(2)

How can the smart mobility agenda be holistic in its approach?

-

(3)

How can public engagement be inclusive when co-creating solutions in smart mobilities planning?

Methodology

In attempting to address these three intellectual questions, we present a two-year project, funded by Innovate UK and Natural Environment Research Council, aiming to co-create solutions with publics. The project, which focused on using smart technologies to reduce traffic congestion, was based in a regional centre in south-west England. The project involved a consortium of four commercial companies, the City and County Councils and the University of Exeter. Engaging publics was pivotal in creating a sense of flow through the project via ongoing two-way dialogue, an understanding of the interruptions in commuting journeys other than when using motor vehicles and a smoother transfer of insights from the research. The work package for the University consisted of two phases. Phase 1 involved the completion of an on-line survey by people aged 17 and over who commuted into or across Exeter to their place of work or study, on average at least three times a week.

Phase 2 consisted of a series of citizen panels (Phase 2i) and an intervention trial (Phase 2ii). Five separate citizen panels were run over a two-week period, one for each of the five types of commuter group identified from the earlier survey in Phase 1. The five groups were people who predominantly, i.e. over 50% of a typical four-week pattern, commuted using a motor vehicle, via public transport, cycled, walked or used a combination of modes within one single journey e.g. Park ‘n’ Ride. Each session was three hours long and included four discussions within groups of three or four people, on specific themes from the survey analysis that were found to be most influential in the decision-making process regarding how people travelled to work or their place of study. Each of the four discussions lasted around 20 min, with occasional prompting as needed to stimulate further conversation. An important part of the process was allowing the narrative within each group to meander wherever it did naturally, within the semi-structured framework of questions (Gardner & Abraham, 2007; Jain et al., 2020). This ensured that the participants were able to share a broad range of experiences, opinions and feelings in a manner that made most sense to them, without being overly constricted by the prompts. Each of the sessions was recorded via audio recorders, and notes made on flip-chart sheets, and Post-It notes.

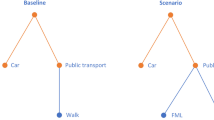

The content of the citizen panels was informed by the key factors identified as influencing commuting behaviour in each group (e.g., fitness, cost, environmental concern), as derived from the Bayesian modelling used for analysing the Phase 1 survey data (see Dawkins et al., 2018, 2019). As detailed in these two earlier papers, constraining the Bayesian priors created distinct groups of survey respondents based on the mode type they predominantly use to commute, as well as the key influencers for each of these commuting behaviours. Thus, exploring how the importance of contextualising quantitative findings with rich qualitative data could be applied specifically with segmentation using Bayesian approaches (Barr et al., 2022). Previous research by Barr et al., (2010, 2013) and Lampkin (2010, 2014), and discussions with local Councils and commercial specialists within the Consortium, also informed the content of the citizen panels.

The citizen panel data was analysed in two ways. First, thematic analysis and three-step coding (Neuman, 2003; Kiger & Varpio, 2020) generated the scope of topic and sub-topic categories regarding the key influencing factors within each of the commuter groups. Second, narrative analysis (Pokorny et al., 2017; Riessman, 1993) identified underlying stories and commonalities across the groups in the context of these categories. These two methods complemented each other by drawing out both vertical and horizontal dimensions, in highlighting the similarities and differences in how the experiences were perceived. The key results from this analysis are presented in the next section.

Results

In line with the aims of the paper, this section provides evidence from the five citizen panels to stimulate critical reflection regarding how to enable publics in visionary transportation systems evolutions, instil a holistic approach to mobility flows and engage publics inclusively in smart mobilities planning. The survey analysis from Phase 1, based on Bayesian statistical techniques, revealed key factors, or mode influencers, for each of the five a priori travel mode choices (motor vehicle, public transport, bicycle, walking and running, and a combination of modes in a single journey). These mode influencers, such as weather conditions or personal fitness, are associated with an individual being more, or less, likely to choose a particular travel mode. Using our Bayesian-based model, we could understand which influencers had the greatest impact on a commuter’s decision-making. For example, an individual was more likely to use a motor vehicle if weather information was ‘often’ or ‘always’ influential, and less likely to use a combination of modes if work parking was ‘good ‘ or ‘excellent’. The most prominent influencers for each commuter mode provided the themes for the citizen panel discussions. Table 1 summarises the themes of each respective citizen panel, based on the mode influencers identified by this Phase 1 analysis.

The citizen panels data, from 40 h of audio recordings, 50 flip-chart sheet notes and 40 Post-It notes, is presented here in three aspects: a visionary evolution for commuting, re-conceptualising the flow of the daily commuting experience and the inclusion of publics in commuter planning. These three aspects align with the themes discussed in "Smart mobilities: technology, engagement and visioning urban futures" section by describing commuter intersectoral viewpoints that dispel widely accepted assumptions about commuting, challenge the car dominated, techno-centric smart mobility paradigm, and suggest mechanisms for local, invested communities to co-create an inclusive transportation system.

A visionary evolution for commuting

Commuting is an everyday behaviour that, for many, has an established, often habitual nature (Clark et al., 2016). Our data revealed that many individuals chose to use different modes on different days, and for a variety of reasons; although as a rule, a cyclical pattern of behaviour was evident. The commuters in our citizen panels generally accepted the need for technological advances in transportation systems and the benefits that it would bring in the future. They were not convinced, however, that the current direction regarding commuting, and travelling in general, was the most effective; they considered the focus was too narrow:

I think there’s too much emphasis on developing cars that drive themselves, rather than looking at not using cars at all. It’s a lot better for the environment… and surely it’d be better if they used all the IT expertise to improve the more sustainable transport options and make them available to everyone rather than assuming people want to buy or use cars in the future. (A, cyclist)

The conventional approach for transport planners has been to make travel times as short as possible, as travel time is perceived as a [negative] cost (Banister, 2008; italics added). Our commuters, however, tended to view the time that they spent commuting in a positive manner, seeing it increasingly as an opportunity to use the time to do what they wanted:

I used to drive and it seemed such a waste of time sitting in all that traffic – all I could do was listen to the radio and look at the car bumper in front of me or the people walking by, going faster than me. Now that I generally take the bus or train, I use the time as I want to. I often switch off and look out of the window at the view or engross myself in a book, and other times I catch up on some work and check my emails. (B, PT user)

There was an acceptance that the actual amount of time, in hours and minutes, that people spent commuting would, more than likely, be greater when using alternative travel modes to a motor vehicle. In the past this may have been important; however, it was evident that spending more of their day commuting did not matter, if the experience was enjoyable:

I don’t think using public transport is quicker than driving, for my particular commute. However, I’m able to use the time better and can work or chill or read the paper or talk to people around me. It’s a nice way to cap off the day and wind down a bit before getting home… as long as there aren’t many interruptions or delays to the journey. With driving I invariably ended up more stressed by the time I got home with all the stop starts and sitting in queues of traffic. (C, PT user)

Therefore, the most compelling narrative, and one of the key findings, was around the sense of well-being that people wanted when commuting. Experiencing such a sense was a reality for some, and a desire for others if, and when, particular aspects improved or were changed. Individual stories relayed, repeatedly, the importance of the daily journey and the impact of their experiences on the rest of their lives. Their commute was not seen as a function in everyday life that had to be endured, more as an important connector between different parts of their lives. The benefits to peoples’ physical and mental health were evident:

I love my walk to work. It clears away the cobwebs, puts me in a great mood and sets me up for the day as I watch and enjoy the world around me. I feel the same whether I'm striding out to get some exercise or taking my time. I can’t think of anything worse than having to be stuck in a car, fighting with all that traffic. (D, walker)

This understanding regarding the role that well-being plays in an everyday activity such as commuting can inform transport planners and IT developers as they envisage commuting patterns, transport networks and customer needs in the future. The value of social interaction was also reiterated in this well-being context:

Cars are so isolating… individuals in little polluting bubbles. We need to meet and chat and travel in groups… so much better for our well-being and […] connecting with each other. What we need is many more trains and buses so we can interact with people around us. That would be great fun, never knowing who you might be sitting next to! (E, PT user)

Finally, this sense of well-being and enthusiasm about people not using cars was portrayed as an aspiration regarding commuting patterns in the future:

It’s great cycling to work. I love it. I don’t have to find time to exercise or go to the gym. When there’s more accurate up-to-date information specific to my route so I know exactly what to wear and can go the best way to make it a bit safer […], I’ll cycle every day as it makes me feel so good. A lot of people I know want to cycle to work more too, so the generation of real-time information that we can rely on and get regular specific updates for, will really help. (F, cyclist)

To recap, we want the future of commuting to embrace the changing perceptions regarding the commuter journey; people want to enjoy the time they spend commuting and use it to further their sense of well-being in life generally. This section shows our participants wanting smart technologies to be integrated in their expansive concepts of commuting, beyond the current motor vehicle-based model. Hence, a visionary evolution to transportation systems involves re-conceptualising the flow of commuting journeys.

Re-conceptualising the flow of the daily commute

Alongside the importance of the commuting experience, is the need for the daily journey to flow smoothly. The current scope for most IT developers and commercial interests regarding improvements to the flow of commuting centres on increasing average speeds of the existing volumes of traffic, rather than on aiming to reduce the overall volume of vehicles on the roads (communication with Consortium Project manager, 15/2/16). Whilst improving the average speed that people travel was of value to some commuters in our citizen panels, many considered that there were several other ways that the flow within their commuting journey could be improved so making the experience more enjoyable and encouraging people who currently drive, to use alternatives:

There’s no information when unexpected events happen like accidents & the bus has to take a different route. Nothing on the website or app - or at the bus stop. I’d like a system that is co-ordinated and reliable, even if I change my mind at the last minute. We have the technology, so why not? If planners and techy people thought about the time that journeys take via public transport and looked at reducing that… and then the real cost would come down too. I’d use public transport all the time if it was more reliable… and flowed better with less interruptions. (G, driver/PT user)

People from the citizen panels, particularly those who predominantly used a combination of modes in a single journey, wanted a more flexible commuter network and transport system. They considered that such flexibility could be created by the provision of accurate, up-to-date travel information about all transport options, which would enable them to decide on their best commuting journey each day, depending on what activities and commitments they had:

Ideally, I’d like to have a number of options each day, which link from my front door to the office to fit around what I’m doing – so taking the bus or train part of the way, with my car or bike & for other days, having shared bike and pre-booked car facilities available via an app, and later buses running should I decide to stay in town after work. That’s what they seem to do in other countries (H, combination of modes)

Integral to the flow of commuter experiences, people discussed the monetary cost of their journeys. This was invariably underpinned by the sentiment that “…car drivers don’t include the real cost of having their car when comparing that to travelling other ways” (J, walker):

The fare structure is so complicated. We need a contactless ticket that allows us to use trains and buses just by swiping our phones as we enter and exit. They also need to do away with the peak and off-peak fares. It’s stupid. One flat rate any time… and why penalise a single? £2.30 when a return’s £2.40! Should be half the return fare, simple. (K, PT user)

Having to share spaces with, and accommodate, other commuters also affects the flow of such journeys. The conflicts that occur in such spaces was discussed at length during all of the citizen panels. Shared spaces are commuter routes used by more than one type of commuter or traveller, for example, joint cycling/walking pathways or arterial roads when no separate cycling lane option is available. Although one person portrayed a congenial temperament, “… we’re all trying to get there and make the best of it” (L, cyclist), many described the intolerance and frustration of commuting along roads or paths with other people travelling at different speeds. Interestingly, this was still the case for those commuters who, on another day, would be the ‘other’ commuter:

I know when I’m driving my car, I get easily frustrated with cyclists on the road. Even though I’m a cyclist, when I’m behind the wheel I’ve got no patience for cyclists and just want them to get out of the way. (M, car driver)

Such feelings led to a clear preference for segregation of the different styles of commuting, which seemed to reflect the “…getting there as quickly as possible and hoping no one slows you down or gets in your way” culture that is prevalent in the UK (N, car driver) and the negativity of the experience when they do:

One of my most terrifying experiences was when I was cycling along a pavement with my two young children on bikes in front of me and as we passed a man he turned round and blocked my way, shouting at me to get off the pavement as I helplessly watched my children cycle on. Fortunately, no harm had come to them by the time I caught them up, but it was awful (P, cyclist).

To reiterate, this section shows our participants challenging the narrow scope used by developers to improve the flow of commuting journeys. That scope needs to be re-conceptualised to include commuting experiences other than via motor vehicles. We argue that smoothing the journey for walkers, cyclists and public transport users by reducing or eliminating the interruptions and unexplained delays enhances the experience and sense of well-being for commuters. By widening their remit and use of smart technologies, planners and IT innovators can improve the flow of all journeys. This would be further enhanced with insights from publics, as discussed next.

The inclusion of publics in commuter planning

Integral to developing future commuting services that meet user needs regarding experience and flow is the inclusion of local people in the transition process. The people in our citizen panels, who were regular users of the local and regional transport networks, discussed the impact they considered they have had on the policies, planning and decision-making by authorities. They interpreted their position very much as a silent consumer who was required to use whatever services were available and put up with them, good or bad. As N (cyclist) put it: “There doesn’t seem to be any two-way communication with the people providing and planning our transport networks and what we do say about the cycling routes and what it’s like to be a cyclist on the main roads seems to go unheard.” A noticeable level of dissatisfaction about the region’s public transport services was voiced:

The experience on public transport can be pretty unpleasant – it’s unreliable, slow, dirty, drivers are rude – and yet it’s so expensive. No wonder people don’t use it. It must be awful for those people who have no choice but to travel on buses and trains. (R, combination of modes).

The perception around using buses and trains, in particular by males, created a further barrier to using public transport:

My husband would never use public transport. He’d rather walk 10 miles than use a bus. He considers such transport is only for second class citizens, those who can’t afford to drive a car (S, PT user).

People also felt that little was being done to raise awareness of the environmental impacts of the increasing volumes of traffic and congestion, which was compounded by an evident distain that local people had been complaining about this for years and no one was listening:

There needs to be a lot more publicity of the pollution that cars cause. It’s been getting worse for years. Now the air quality in Exeter is often below European standards. The information is on the Council’s website but who has time or inclination to look in the morning before jumping in their car… and it needs to be presented so people can understand the significance of the figures (T, walker)

Finally, and even though there was a sense of powerlessness with the Authorities, many of the discussions amongst the five citizen panels focused on using the opportunity in a constructive manner, to talk about their ideas on how to improve commuting experiences for themselves and fellow travellers. This positivity was coupled with a sense of community and responsibility towards addressing these issues so that everyone was included in the transition, as they are all part of the Exeter population:

Little emphasis is put on the social value of travelling. We are all part of this region and it is in our interests to protect and develop it in a way that means we can continue to be proud of living here. It always seems weird to me that we are a social species living in a car dominated world, travelling on our own in miles of vehicles. However much they manage to speed up the traffic, and I guess that would improve my commute to a degree, I’d much prefer if they looked at improving the public transport and cycling networks and making commuting in the region available to everyone… and a good experience for everyone. They just need to listen to what’s being said here and to the Council and to other people… (V, combination of modes)

This final section shows the disconnect between users and planners, as our participants perceive negligible two-way dialogue in current transportation system developments. We argue that the participatory method of engaging with people, used in our citizen panels, expediates the sharing of valuable intersectoral knowledge and empowerment of publics to identify local community-focused solutions, based on daily commuting experiences.

These detailed findings regarding a visionary evolution for commuting, the re-conceptualisation of the daily commute flow and the inclusion of publics in commuter planning inform our understanding about the mechanisms by which we can engage publics in the transition to smart mobilities. The next section discusses the wider implications of this work.

Discussion

Based on the research findings, this section discusses our three propositions. First, that enabling publics should lead to a visionary evolution in the development of sustainable transportation systems. Second, that commercial interests, public bodies and IT innovators must employ a holistic approach to mobility flows. Arising out of these two findings, third, that processes engaging publics need to be inclusive when co-creating solutions in the transition to smart mobilities.

The detail in the Results section reveals the value of co-creation research for engaging publics in the transition to smart mobilities. Such an approach elicited in-depth narratives around the future of commuting, the flow of the daily commute and the inclusion of publics in smart mobility planning, highlighting key concerns for the people who are embroiled in the issues as part of their everyday lives. For example, the importance of a commute with minimal interruptions (panellist C) or reliable real-time traffic information (panellist G). We need to use publics to help create the visions and realities of future mobilities, ensure inclusiveness for all and widen the current techno-centric focus of the smart mobility agenda (cf. Biswas, 2016; Valkenburg & Cotella, 2016). This is captured succinctly by Panellist A, “… there’s too much emphasis on developing cars that drive themselves, rather than looking at not using cars at all.” Other signposts within the narrative include the desire to use sustainable commuter modes more frequently when real-time information is available (panellist F), and a concern that the lack of publicity about pollution means people are ill-informed about the environmental impact of their car use (panellist T). To ensure critical reflection (Luusua et al., 2015) and creativity mindsets (Fredrickson, 2001) are integral to the process, it is essential these narratives are shared in an expansive manner and public participation is placed at the heart of policy development. This may be best achieved via open access to data collected from publics, who are arguably the true owners (Montgomery, 2017; Asswad and Gomez, 2021), and by open access to institutions responsible for policy creation and implementation. If all Agencies positioned people at their centre, as the common spotlight, we can perhaps start to resolve some of the mismatches in the smart mobilities agenda.

The process of digitalisation, which is already an integral part of the smart mobilities agenda (D’Amico et al., 2022; Sourbati & Behrendt, 2021), is changing how we connect to, and with, each other and brings people together who might otherwise never have met. Via the digital frontier “…individuals and organisations can produce vast streams of content that have the potential to reach a worldwide audience who can interact with it” and accessibility to communities and interest groups who can manufacture changes that could not be achieved by individuals on their own (Swart et al., 2017 p. 910). Thus, digitalisation provides scope for IT developers to promote and facilitate people participation and inclusion, conditional to them continuing to shift perceptions of publics from passive recipients to active participants (Lundkvist & Yakhlef, 2004; Anderson et al., 2010). As discussed in "Enabling publics to be visionary" section, this shift relies on a focus of relationship building (Cook & Zurita, 2019) and empowerment (Chlivers & Kearnes, 2015), rather than information transfer (Broockman & Kalla, 2016). An equilibrium does need to be met, however, as new products from developers tend to be commercialized without necessarily solving user problems (Kristensson et al., 2004) and ideas generated by publics tend to be creative but unfeasible (Magnusson, 2009). Social science researchers are experts in extracting relevant attitudes, behaviours and decision- making processes from publics and ensuring perspectives and targets of publics are central, removing ‘expert-lay’ divisions (Esmene, 2021; Wynne, 1992). For example, the need to simplify public transport fare structures and the disincentives (panellist K) go beyond the big data view of what certain groups might want. Such extraction can enable insights from publics to inform the digitalisation of future transportation systems at conceptualisation and design stages.

Assimilating co-creation and digitalisation creates the potential to develop innovative yet pragmatic solutions. As part of this, the scope for improving flow within transport networks needs to be extended to enable commercial interests and innovators to employ a holistic approach to mobility flows. The experience of urban and transport planning in the last 50 years has demonstrated that an excessive focus on technical performance has led to a lack of understanding of those people, from occasional travellers to daily commuters, who use the transport system (Anderson et al., 2010; Martens, 2017). The current mobility paradigm will only be truly ‘smart’ if the key players do not limit themselves to technological developments and making modifications, or tweaks, within the existing framing (Barr et al., 2021). We need, and have an opportunity for, a step change. The Results here have revealed a clear narrative that, for example, flow is no longer about getting from A to B as quickly as possible; nor is it about enduring the commuting time as ‘wasted’ or perceiving it as a negative cost. As shown in "A visionary evolution for commuting" section, commuters do not mind spending more time commuting, if the journey is smooth and enjoyable. These findings concur with earlier studies by, for example, Lyons et al. (2007), Jain and Lyons (2008) & Calvert et al. (2019). There needs to be a shift in perception and focus towards valuing the time people spend commuting, their overall well-being and the possibilities and opportunities that such experiences can offer. For example, Chatterjee et al. (2017) found that increasing commute time reduces mental health, and job and leisure time satisfaction. IT innovation has a key role to play in changing those perceptions and the capacity to adapt systems to cater for the changing requirements of consumers (Benevolo et al., 2016). To achieve that, however, planners and developers need a greater emphasis on engaging with people who use, and perhaps more importantly do not use, the transport networks and an awareness of intersectionality to better appreciate the differences between social groupings and address the inequalities invariably overlooked, and not possible, with big data analysis. Refer to "Mobilising user inclusivity" section.

The narratives from the citizen panels highlighted that improving the flow of commuting is fundamentally about improving the commuter experience. For the commuters in our study, this entails smoothing out the flow within the journey, reducing interruptions and incorporating individual variability in daily activities. The benefits to mental and physical health were clear advantages for many commuters, who prioritised those aspects over, for example, the monetary cost or actual time a journey took. As our commuters alluded to, people valued their travel time as ‘down time’ or Me Time, during which they did what they wanted, such as reading a book, gazing out the window or switching off (cf. Jain & Lyons, 2008). People need slow time to reflect and re-order the chaos in everyday life (Freudendal-Pedersen, 2009). IT developers have the capacity to cater for such requirements by providing accurate and reliable real-time travel information (Regalado, 2014), and a seamless door-to-door service (Benevolo et al., 2016) so people, such as panellist H in our study, can plan their journeys and feel more relaxed about the experience, whilst maintaining a high level of flexibility when deciding which travel mode(s) to use. Also, the provision of Wifi, not only on buses and trains, but also at the bus and train stations allows people to continue using the Internet access whilst waiting for their connection (Jain et al., 2018) and introducing Intelligent Traffic Systems along arterial roads can give priority to buses and cyclists (Rutgersson, 2013). Thus, providing a more inclusive approach to improving the flow of journeys and meeting transport needs for the future.

Both IT developers and publics have the desire to improve the flow of commuting experiences within their respective visions of future transport networks and services. The mechanisms and focus of those improvements, however, differ between the two groups. An underlying theme of the narrative described earlier, in particular by panelists C, D and E, was the role and impact that having a sense of well-being plays during the daily commute. In contrast, panelist P described a stressful experience due to conflict over how a shared space should be used and panelist M, the challenge when using different modes in a shared space on different days. Developers need to understand, and focus on, the key issues that matter for these different users, when endeavouring to engage with a wide representation of publics. For example, the frustration for a walker when bikes encroach on their pathway or the importance of highly granular, reliable real-time traffic and weather information so commuters can make informed choices. Papa and Lauwers (2015) argue the need for interrelation between the physical and the digital in the context of smart mobilities, as well as the local perspective. Citizen populations are invested in the region in which they live and work, as reflected in panellist V’s sense of community, positivity in believing that current traffic congestion problems can be improved and responsibility in wanting to be actively involved in the changes. It is important that this positivity is valued by planners and policy makers in listening to the needs and desires of the population, transport users and non-users alike – and more so, ensuring that what is being heard is then acted upon and integrated accordingly. As discussed in "Contesting the smart mobility paradigm" and "Mobilising user inclusivity" sections, planners and local Councils typically propose narrow, techno-centric solutions within existing infrastructure and framing with poor prioritisation of issues such as accessibility, usability and service quality and lacking psychosocial considerations such as emotional and financial. Instead, by using the nuanced participatory approach discussed in "Enabling publics to be visionary" section, these personnel can build relationships with the community by running events, being transparent about feasible smart technology options and empowering citizens to feedback during a project’s conceptualisation phase. A sentiment echoed by panellist N. The positivity, energy, and enthusiasm of the local population is a crucial tool to drive the smart mobilities transition.

Finally, inclusion requires a shift in the emphasis away from perceptions that people who drive are people making ‘bad’ choices and should feel guilty, towards a celebration of people who are using more sustainable modes. Interestingly, the same sense of freedom and flexibility that was so appealing when cars were first introduced (Dennis & Urry, 2009), is still central to the vision that commuters have today regarding their future transport needs and multi-modal travel choices away from using cars (Barceló, 2015; cf. Simmel, 1997 and Freudendal-Pedersen, 2009). During all the citizen panels, there was a strong sense that people want to be involved in the transition, to inform and be part of the decision-making to create commuting experiences that cater for spontaneity and the flexibility of leading a busy and unpredictable lifestyle—a freedom of movement and a freedom of mind.

Concluding remarks

The transition to smart mobilities is a process that must be all-encompassing and involve users and non-users alike. The ascendance of big data has produced new opportunities for business and IT organisations and enabled more efficient and quicker real-time travel decision-making and greater accessibility for some members of society. It is likely, however, that the social inequalities already present will be perpetuated by the smart city concept, unless we address the historical models of engaging with publics. This paper makes three key propositions for researchers. First, engaging publics should lead to a visionary evolution in the development of sustainable transportation systems. Second, commercial interests, public bodies and IT innovators must employ a holistic approach to mobility flows. Third, processes engaging publics need to be inclusive when co-creating solutions in the transition to smart mobilities. Fundamental to all three is the necessary transition from passive individuals accepting services as they are, to participatory models of mobility underpinned by relationship building and nurturing, active listening, and empowerment. As shown in this study, this contemporary approach draws out the very aspects of mobility patterns and decision-making that are overlooked by, or not possible with, the big data-driven models. Through an awareness of intersectionality, place-contextualisation, and in partnership collaborations between local authorities, technology providers and researchers, the key drivers of why people behave the way they do can inform smart transportation systems. By enhancing the flow of innovation and insights from publics, we can ensure potential users of new transportation systems and technological advancements are connected in a two-way dialogue from conceptualisation. We must also re-engineer how the flow within transportation systems is more about the experience and inclusivity of multi-modal journeys than about reducing travelling time. If not, the social inequalities are only likely to widen further.

References

Agichtein, E., Castillo, C., Donato, D., Gionis, A. & Mishne, G. (2008). Finding high-quality content in social media.,In Proceedings of the international conference on web search and web data mining (pp. 183–193)

Albino, V., Berardi, U., & Dangelico, R. M. (2015). Smart cities: Definitions, dimensions, performance, and initiatives. Journal of Urban Technology, 22(1), 3–21.

Andersson, E., Burall, S., & Fennell, E. (2010). Talking for a Change. Involve.

Asswad, J., & Marx Gómez, J. (2021). Data ownership: A survey. Information, 12(11), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12110465

Banister, D. (2008). The sustainable mobility paradigm. Transport Policy, 15(2), 73–80.

Barceló, J. (2015). ITS, Smart Cities and Smart Mobility. Presentation at Center of Transportation Studies, University of Minnesota

Barr. S., Gilg, A. W. & Shaw, G. (2013). Social marketing for sustainability. Developing a community of practice for behavioural change in tourism travel. University of Exeter.

Barr, S. W., Lampkin, S. R., Dawkins, L. D., & Williamson, D. B. (2021). Smart cities and behavioural change: (Un) sustainable mobilities in the neo-liberal city. Geoforum, 125(8), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.06.010

Barr, S. W., Lampkin, S. R., Dawkins, L. D., & Williamson, D. B. (2022). ‘I feel the weather and you just know’. Narrating the dynamics of commuter mobility choices. Journal of Transport Geography, 103(6), 103407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103407

Barr, S., Shaw, G., Coles, T., & Prillwitz, J. (2010). “A holiday is a holiday”: Practicing sustainability, home and away. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 474–481.

Barrero, F., Toral, S., Vargas, M., Cortes, F., & Milla, J. M. (2010). Internet in the development of future road-traffic control systems. Internet Research, 20(2), 154–168.

Bartscherer, T., & Coover, R. (Eds.). (2011). Switching codes: Thinking through digital technology in the humanities and the arts. University of Chicago Press.

Batty, M., Axhausen, K. W., Giannotti, F., Pozdnoukhov, A., Bazzani, A., Wachowicz, M., Ouzounis, G., & Portugali, Y. (2012). Smart cities of the future. European Physical Journal Special Topics, 214(1), 481–518.

Bélissent, J. (2010). “What Is A City, Let Alone A ‘Smart’ One?” Jennifer Belissent’s Blog For Vendor Strategy Professionals, May 21. Retrieved November 15, 2016, https://www.forrester.com/blogs/10-05-21-what_is_a_city_let_alone_a_smart_one/

Bell, R., Mullins, P. D., Herd, E., Parnell, K., & Stanley, G. (2021). Co-creating solutions to local mobility and transport challenges for the enhancement of health and wellbeing in an area of socioeconomic disadvantage. Journal of Transport & Health, 21(2), 1–12.

Benevolo, C., Dameri, R. P., & D’Auria, B., et al. (2016). Smart mobility in Smart city: Action taxonomy, ICT intensity and public benefits. In T. Torre (Ed.), Empowering organizations. Lecture notes in information systems and organisation (p. 11). International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23784-8_2

Berry, D. M. (2012). Understanding digital humanities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Biswas, A. (2016). Insight on the evolution and distinction of inclusive growth. Development in Practice, 26(4), 503–516.

Bogers, M., Hadar, R., & Bilberg, A. (2016). Additive manufacturing for consumer-centric business models: Implications for supply chains in consumer goods manufacturing. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 102(1), 225–239.

Boisjoly, G., & Yengoh, G. T. (2017). Opening the door to social equity: Local and participatory approachesto transportation planning in Montreal. European Transport Research Review, 9, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12544-017-0258-

Borén, S., Nurhadi, L., Nya, H., Robèrt, K.-H., Broman, G., & Tyrgg, L. (2017). A strategic approach to sustainable transport system development—part 2: The case of a vision for electric vehicle systems in southeast Sweden. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140(1), 62–71.

Broockman, D., & Kalla, J. (2016). Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science, 352(6282), 220–224.

BSI. (2014). Smart city framework. British Standard Institution Publication.

Burall, S., & Shahrokh, T. (2010). What the public say. Involve.

Calvert, T., Jain, J., & Chatterjee, K. (2019). When urban environments meet pedestrian’s thoughts: Implications for pedestrian affect. Mobilities, 14(5), 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1613025

Carvalho, L. (2015). Smart cities from scratch? A socio-technical perspective. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 43–60.

Cecere, L. (2014). Supply chain metrics that matter. Wiley.

Cervero, R. (2009). Transport infrastructure and global competitiveness: Balancing mobility and livability. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 626(1), 210–225.

Chen, C., Chiang, R. H. L., & Storey, V. C. (2012). Business intelligence and analytics: From big data to big impact. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 36(4), 1165–1188.

Chen, C., Ma, J., Susilo, Y., Liu, Y., & Wang, M. (2016). The promises of big data and small data for travel behaviour (aka human mobility) analysis. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 68(7), 285–299.

Chilvers, J., & Kearnes, M. (Eds.). (2015). Remaking participation: Science, environment and emergent publics (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203797693

Chourabi, H., Nam, T., Walker, S., Gil-Garcia, J.R., Mellouli, S., Nahon, K., Pardo, T.A. & Scholl, H.J. (2012). Understanding smart cities: An integrative framework. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii international conference on system science (HICSS) (pp. 2289–2297)

Cichosz, M. (2013). IT solutions in logistics of smart bike-sharing systems in urban transport. Management, 17(2), 272–283.

Clark, J., & Curl, A. (2016). Bicycle and car share schemes as inclusive modes of travel? A socio-spatial analysis in Glasgow, UK. Social Inclusion, 4(3), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v4i3.510

Clark, W. C., van Kerkhoff, L., Lebel, L., & Gallopin, G. C. (2016). Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of the United States of America, 113(17), 4570–4578.

Cook, B. R., & Zurita, M. D. L. M. (2019). Fulfilling the promise of participation by not resuscitating the deficit model. Global Environmental Change, 56(3), 56–65.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, 139–167.

D’Amico, G., Arbolino, R., Shi, L., Yigitcanlar, T., & Ioppolo, G. (2022). Digitalisation driven urban metabolism circularity: A review and analysis of circular city initiatives. Land Use Policy, 112(1), 105819.

Davies, S., McCallie, E., Simonsson, E., Lehr, J., & Duensing, S. (2009). Discussing dialogue: perspectives on the value of science events that do not inform policy. Public Understanding of Science, 18(3), 338–353.

Dawkins, L. C., Williamson, D. B., Barr, S. W., & Lampkin, S. R. (2018). Influencing transport behaviour: A Bayesian modelling approach for segmentation of social surveys. Journal of Transport Geography, 70(5), 91–103.

Dawkins, L. C., Williamson, D. B., Barr, S. W., & Lampkin, S. R. (2019). “What drives commuter behaviour?”: Bayesian analysis for apposing predominant behaviours in social surveys. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 183(1), 251–280.

Day, H. (2021). Inequalities in sustainable transport use in Aotearoa New Zealand: gender, intersectionality, and commuting using sustainable modes (Thesis, Master of Public Health). University of Otago. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10523/10688

de Leeuw, S., Cameron, E. S., & Greenwood, M. L. (2012). Participatory and community-based research, indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: A critical engagement. Canadian Geographer-Geographe Canadien, 56(2), 180–194.

Dennis, K., & Urry, J. (2009). After the car. Polity Press.

Ding, J.-W., Wang, C.-F., Meng, F.-H., & Wu, T. Y. (2010). Real-time vehicle route guidance using vehicle-to-vehicle communication. IET Communications, 4(7), 870–883.

Esmene, S. (2021). Colonising public engagement: Revealing the “expert-lay” divisions formed by academia’s dominant praxis. Area, 53(1), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12676

Featherstone, H., Wilkinson, C. & Bultitude, K. (2009). Public engagement map: report to the science for all expert group. Project Report. Science Communication Unit, UWE.

Freudendal-Pedersen, M. (2009). Mobility in daily life: Between freedom and Unfreedom. Ashgate Publishing.

Freudendal-Pedersen, M., Kesselring, S., & Servou, E. (2019). What is smart for the future city? Mobilities and automation. Sustainability, 11, 221–242.

Gardner, B., & Abraham, C. (2007). What drives car use? A grounded theory analysis of commuters’ reasons for driving. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 10(3), 187–200.

Gehl, J. (2013). Cities for people. Island Press.

Goodall, W., Dovey-Fishman, T., Bornstein, J., & Bonthron, B. (2017). The rise of mobility as a service: Reshaping how urbanites get around. Deloitte Review, 20(1), 111–129.

Gouveia, J.P., Seixas, J. & Giannakidis, G. (2016). Smart city energy planning. In Proceedings of the 25th International conference companion on world wide web—WWW ’16 companion, Montréal, QC, Canada, 11–16 April, (pp. 345–350)

Graham, M., & Shelton, T. (2013). Geography and the future of big data, big data and the future of geography. Dialogues in Human Geography, 3(3), 255–261.

Grand, A., Davies, G., Holliman, R., & Adams, A. (2015). Mapping Public engagement with research in a UK University. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0121874. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121874

Gupta, D., Spitzberg, B., Tsou, M. H., Gawron, M., & An, L. (2012). Revolution in social science methodology: Possibilities and pitfalls. San Diego State University.

Haghani, A., Hamedi, M., Sadabadi, K. F., Young, S., & Tarnoff, P. (2010). Data collection of freeway travel time ground truth with bluetooth sensors. Transportation Research Record, 2160(1), 60–68.

Hemment, D., & Townsend, A. (Eds.). (2013). Smart citizens (Vol. 4). Future Everything Publications.

Hey, T., Tansley, S., & Tolle, K. I. (2009). The fourth paradigm: Data-intensive scientific discovery. Microsoft Research.

Holliman, R. (2015). Valuing publicly engaged research Euroscientist 4 November. Online Retrieved December 7, 2017, from www.euroscientist.com/valuing-publicly-engaged-research

Holliman, R., Adams, A., Blackman T., Collins, T., Davies, G., Dibb, S., Grand, A., Holti, R., McKerlie, F., Mahony, N. & Wissenburg, A. Eds (2015). An open research University. The Open University. Eds Online Retrieved December 5, 2017 http://oro.open.ac.uk/44255

Holmwood, J. (2014). From social rights to the market: Neoliberalism and the knowledge economy. International Journal of Science Education, 33(1), 62–76.

Horst, M., & Michael, M. (2011). On the shoulders of idiots: Re-thinking science communication as “event.” Science as Culture, 20(3), 283–306.

Ilie, D.G., Neghina, R.-A., Manescu,V.-A., Gaciu, M. & Militaru, G. (2020). New media, old problems: Social stratification, social mobility and technology usage. In 14th international technology, education and development conference (INTED) (pp. 6319–6326). https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2020.1707

Jahangiri, A., & Rakha, H. A. (2015). Applying machine learning techniques to transportation mode recognition using mobile phone sensor data. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 16(5), 2406–2417.

Jain, J., Bartle, C., & Clayton, W. (2018). Continuously connected customer. Report by Centre for Transport and Society.

Jain, J., & Lyons, G. (2008). The gift of travel time. Journal of Transport Geography, 16(2), 81–89.

Jain, T., Johnson, M., & Rose, G. (2020). Exploring the process of travel behaviour change and mobility trajectories associated with car share adoption travel. Behaviour & Society, 18, 117.

Janowicz, K. (2012). Big data GIScience? http://stko.geog.edu/bigdatagiscience2012/bigdatapanel_intro.pdf

Jasanoff, S. (Ed.). (2004). States of knowledge: The co-production of science and the social order. Routledge.

Jones, P., & Evans, J. (2012). The spatial transcript: Analysing mobilities through qualitative GIS. Area, 44(1), 92–99.

Kammerlander, M., Schanes, K., Hartwig, F., Jager, J., Omann, I., & O’Keeffe, M. (2015). A resource- efficient and sufficient future mobility system for improved well-being in Europe. European Journal of Futures Research, 3(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-015-0065-x

Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 846–854.

Kim, Y., & Slotegraaf, R. J. (2016). Brand-embedded interaction: A dynamic and personalised interaction for co-creation. Marketing Letters, 27(1), 183–193.

Kitchin, R. (2014). The data revolution: Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. Sage.

Kostakos, V., Ojala, T., & Juntunen, T. (2013). Traffic in the smart city: Exploring city-wide sensing for traffic control center augmentation. IEEE Internet Computing, 17(6), 22–29.

Koster, R., Baccar, K., & Lemelin, R. H. (2012). Moving from research ON, to research WITH and FOR Indigenous communities: A critical reflection on community-based participatory research. Canadian Geographer-Geographe Canadien, 56(2), 195–210.

Kristensson, P., Gustafsson, A., & Archer, T. (2004). Harnessing the creative potential among users. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(1), 4–14.

Kusters, A. (2019). Boarding Mumbai trains: The mutual shaping of intersectionality and mobility. Mobilities, 14(6), 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1622850

Lampkin, S. R. (2010). Exploring why individuals acquire the motivation to mitigate climate change. Ph.D. thesis. University of East Anglia

Lampkin, S. R. (2014). The impact of withdrawing a structured initiative aimed at engaging departments in sustainable activities, at a UK university. In W. Leal Filho, L. Brandli, O. Kuznetsova, & A. Paço (Eds.), Integrative approaches to sustainable development at university level making the links (pp. 321–330). Springer.

Lauwers, D. & Papa, E. (2014). Smart mobility, beyond technological innovation: mobility governance for smarter cities and smarter citizens. Paper presented at the Studiedag IDM “De toekomst van Mobiliteit in Vlaanderen”, Gent, December.

Litman, T. (1998). Measuring transportation: Traffic mobility and accessibility. Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Liu, Y., Liu, X., Gao, S., Gong, L., Kang, C., Zhi, Y., Chi, G., & Shi, L. (2015). Social sensing: A new approach to understanding our socio-economic environments. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(3), 512–530.

Lundkvist, A., & Yakhlef, A. (2004). Customer involvement in new service development: A conversational approach. Managing Service Quality, 14(2/3), 249–257.

Luusua, A., Ylipulli, J., Jurmu, M., Pihlajaniemi, H., Markkanen, P. & Ojala, T. (2015). Evaluation Probes. In Proceedings of the CHI’15: The acm chi conference on human factors in computing systems, 18–23 April

Lyons, G., Jain, J., & Holley, D. (2007). The use of travel time by rail passengers in Great Britain. Transportation Research, 41(A), 107–120.

Magnusson, P. R. (2009). Exploring the contributions of involving ordinary users in ideation of technology-based services. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(5), 578–593.

Majumdar, S. R. (2017). The case of public involvement in transportation planning using social media. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 5(1), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2016.11.002

Mak, V., Gisches, E. J., & Rapoport, A. (2015). Route vs. segment: An experiment on real-time travel information in congestible networks. Production and Operations Management, 24(6), 947–960.

Manika, D., & Golden, L. L. (2016). Advances in prior knowledge conceptualizations: Investigating the impact on health behaviour. In K. Plangger (Ed.), Developments in marketing science: Thriving in a new world economy (pp. 328–328). Springer.

Martens, K. (2017). Transport Justice: designing fair transportation systems. Routledge.

McCallie, E., Bell, L., Lohwater, T., Falk, J., Lehr, J., Lewenstein, B., Needham, C. & Wiehe, B. (2009) Many experts, many audiences: Public engagement with science and informal science education. A CAISE Inquiry Group Report. Washington DC: Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education (CAISE).

Montgomery, J. (2017). Data sharing and the idea of ownership. New Bioethics, 23(1), 81–86.

Nared, J. (2020). Participatory transport planning: the experience of eight European metropolitan regions. In J. Nared & D. Bole (Eds.), Urban book series (pp. 13–29). Springer.

NCCPE (2010). What is Public Engagement? Retrieved December 17, 2017, from http://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/explore-it/what-public-engagement

Neuman, W. L. (2003). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Allyn & Bacon.

Nickpour, F. & Jordan, P.W. (2013). Accessibility in public transport—a psychosocial approach. In 4th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE), Advances in human aspects of road and rail transportation (pp. 341–350)

Paiva, S., Ahad, M. A., Tripathi, G., Feroz, N., & Casalino, G. (2021). Enabling technologies for urban smart mobility: Recent trends. Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors, 21(6), 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21062143

Pangbourne, K. (2017). Who fits under Smart Mobility’s umbrella? A critical exploration of Mobility as a Service. In Proceedings at RGS-IBG annual conference

Papa, E. & Lauwers, D. (2015). Smart mobility: Opportunity or threat to innovate places and cities? In 20th international conference on urban planning and regional development in the information society (REAL CORP) (pp. 543–550)

Papangelis, K., Nelson, J. D., Sripada, S., & Beecroft, M. (2016). The effects of mobile real-time information on rural passengers. Transportation Planning and Technology, 39(1), 97–114.

Perrons, R. K., & McAuley, D. (2015). The case for ‘n=all’: Why the Big Data revolution will probably happen differently in the mining sector. Resources Policy, 46(2), 234–238.

Pokorny, H., Holley, D., & Kane, S. (2017). Commuting, transitions and belonging: The experiences of students living at home in their first year at university. Higher Education, 74(3), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0063-3

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The future of competition: Co-creating unique value with customers. Harvard Business School Press.

RCUK (2015). RCUK Review of Pathways to Impact: Summary. Retrieved December 6, 2017, from www.rcuk.ac.uk/documents/documents/ptoiexecsummary-pdf

Regalado, A. (2014). Data and decision making. MIT Technology Review, 117(2), 61–63.

Parliamentary Report (2000). Science and Technology Committee – Third Report. Retrieved December 7, 2017, from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199900/ldselect/ldsctech/38/3802.htm

Ribeiro, P., Dias, G., & Pereira, P. (2021). Transport systems and mobility for smart cities. Applied System Innovation, 4(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi4030061

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis (Vol. 30). Sage.

Rönkkö, E., Luusua, A., Aarrevaara, E., Herneoja, A., & Muilu, T. (2017). New resource-wise planning strategies for smart urban-rural development in Finland. Systems, 5(10), 1–12.

Rossetti, J. F. (2015). Towards smart mobility. Readings on Smart Cities, 1(5)

Rutgersson, A. (2013). A study of cyclists’ need for an Intelligent Transport System (ITS). Master’s Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology

Sassi, A., & Zambonelli, F. (2014). Coordination Infrastructures for future smart social mobility services. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 29(5), 78–82.

Scanlon, E. (2014). Scholarship in the digital age: Open educational resources, publication and public engagement. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 12–23.

Schaffers, H., Komninos, N., Pallot, M., Trousse, B., Nilsson, M., & Oliveira, A., et al. (2011). Smart cities and the future internet: Towards cooperation frameworks for open innovation. FIA 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 6656In J. Domingue (Ed.), The future internet (pp. 431–446). Springer.

Schuetze, H. G. (2010). The ‘third mission’ of universities: engagement and service. In P. Inman & H. G. Schuetze (Eds.), The community engagement and service mission of universities (pp. 13–31). Niace.

Simmel, G. (1997). Simmel on culture: Selected writings. Sage.

Singh, K. (2016) Smart urban mobility for safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable cities. In Report for UN habitat III conference, Quito 17–20 October.

Smith, G., Sochor, J., & Karlsson, I. C. M. (2018). Mobility as a Service: Development scenarios and implications for public transport. Research in Transportation Economics, 69(3), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2018.04.001

Sourbati, M., & Behrendt, F. (2021). Smart mobility, age and data justice. New Media & Society, 23(6), 1398–1414.

Staley, K. (2009). Exploring Impact: Public Involvement in NHS. Involve: Public Health and Social Care Research.

Steinfeld, E. (2013). Creating an inclusive environment, Trends in Universal Design, 52.