Abstract

While a couple of decades ago homeownership used to be a privilege of the few, nowadays most households in developed countries are living in their own four walls. One of the reasons behind this shift are government policies aimed at promoting homeownership and making it more financially feasible. Among these policies, there is a wide range of instruments reducing the costs of mortgage loan interest. Recently, the promotion of homeownership has also become an important issue in some of the former socialist countries. An example of that is a policy of the Polish government called “Family’s own home”. The aim of this policy was to provide financial support for young households who are particularly vulnerable to the difficult housing situation in Poland. Due to huge price increases between 2006 and 2008, and in connection with a short supply of rental housing, many households have been unable to find an affordable dwelling in recent years. The “Family’s own home” policy, initiated in 2007, was the government’s response to this problem. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the outcomes of this policy, which was terminated at the end of 2012 because of a public finance crisis. Three research questions are addressed: (1) what was the relationship between government support and residential construction, housing prices, and mortgage loan interest rate, (2) what was the spatial distribution of government support, and (3) how was it related to the spatial distribution of housing prices, incomes, and housing affordability?

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A large number of households in developed countries have made the desire of becoming an owner of a house or a dwelling come true. While a couple of decades ago only a minority of households could afford homeownership (particularly in urban areas), now the rates generally exceed 50 %, and sometimes even reach 70–80 % (US Census Bureau 2011; Andrews and Sánchez 2011). There is obviously a range of factors that contributed to this change, but here we would like to focus on one of them, namely the role of government policies. Practically all the Western European countries and—what is probably the most famous case—the USA, have been pursuing some kind of homeownership promoting policies in recent decades. In particular, there has been a wide range of policies aimed at reducing the costs of mortgage loan interest. Most housing market transactions nowadays are being financed with mortgage loans, so financial support of the government might be a significant relief for home buyers. However, there is much controversy about the actual outcomes of such policies.

The housing situation in the former socialist countries is much different than in the developed countries. Quite surprisingly, homeownership rates are very high—a fact which demonstrates that a large number of homeowners need not necessarily reflect the overall economic prosperity of a country. For example, the highest homeownership rates among the EU member states can be found not in Western Europe, but in countries like Estonia (96 %), Romania (96 %), and Slovak Republic (92 %), source of data: Ministry of the Interior… (2010). Unusually high homeownership rates in post-socialist countries can be explained by several factors. One of them is the massive privatization of dwellings from the housing stock constructed or taken over by the state in socialist times (Buckley and Tsenkova 2001). Country-specific factors also played a certain role. For example, Poland had a relatively high number of owner-occupied single family houses even under socialism, because a significant share of land (mostly in rural areasFootnote 1) was private. Despite high homeownership rates, the overall housing situation in transition countries is far from satisfactory. This is particularly true for young households, because there is no sufficient supply of new affordable dwellings. Despite some efforts to stimulate residential construction, two decades after the fall of socialism the former socialist countries are still lagging much behind of Western Europe, as the report “Housing Statistics in the European Union 2010” revealed (Ministry of the Interior … 2010).

Housing conditions in Poland are problematic even compared to other Central and East European (CEE) transition countries (see the section “Housing situation in Poland” for more details). The most serious concern in the last years has been an increase of housing prices, which took place especially between 2006 and 2008. A large number of young people entering the housing market at that time were faced with increasingly difficult conditions. In this context, a new law was passed by the parliament in September 2006.Footnote 2 This act was the foundation for a policy, which came into force on 1 January 2007, and was later nicknamed “Family’s own home” (pol. “Rodzina na swoim”). The principle of this policy was to provide subsidized mortgage loans for households who acquire their first dwelling. “Family’s own home” soon became very popular, and the government had to spend increasingly large funds to grant the subsidies. Although mortgage subsidies were a relatively small position in the total sum of government expenditures, due to a high level of public debt the policy was terminated at the end of 2012.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the outcomes of “Family’s own home” policy in the context of housing affordability in Poland. Housing policies are generally intended to make housing more affordable. That can be done either directly, by providing subsidies which reduce households’ housing expenditures, or indirectly, by increasing housing supply (what, ceteris paribus, should cause the prices to fall). A special emphasis in this paper will be placed on spatial analysis. Although there has been recently much discussion in Poland about the affordability of housing, there is still no exact knowledge about the spatial differentiation of this phenomenon. This is a very important question, particularly from the perspective of policy making, because a socially responsible policy should address mostly these areas where housing is at least affordable. How can the “Family’s own home” policy be judged from that perspective was one of the questions that inspired this article.

The following parts of the paper are structured as follows. After the theoretical part based on a literature review, a brief overview of housing situation in Poland is presented. Then, the general principles and legal rules of the investigated policy are introduced. An empirical part follows, in which the following research questions are being addressed in respective order: (1) what was the relationship between government support and residential construction, housing prices and mortgage loan interest rates, (2) what was the spatial distribution of government support, and (3) how was it related to the spatial distribution of housing prices, incomes, and housing affordability? The last section of the article provides conclusions and discussion.

Promotion of homeownership as a housing policy

What all the various housing policies have (or should have) in common, is that they are aimed at making housing more available and more affordable, especially for households with lower incomes. In this context one could ask what is the rationale for supporting homeownership with public funds. Taxpayers’ money is usually scarce, and there are other possible ways to improve housing conditions, for example by supporting the construction of rental housing. In the literature both the arguments for, and against, the promotion of homeownership can be found (Hamby 2011). The proponents argue that a high rate of homeownership brings important social and economic benefits. Let us shortly list just a couple of them. Firstly, it is believed that real estate investments are a safe way of accumulating wealth. Secondly, being an owner, especially of a single-family house, tends to be associated with high social status. And finally, there seems to be a widespread opinion that homeowners are more strongly “rooted” in their neighborhoods, so they are more likely to support initiatives that bring benefits in the long term. However, under certain circumstances it might become problematic to have strong roots with a particular place. This is the main argument against promoting homeownership among people with an unstable employment situation. Namely, high costs of relocation in comparison to rented housing make homeowners less mobile, and therefore more vulnerable to unemployment. So, especially countries with high unemployment rates should be cautious with implementing homeownership promoting policies. In this context the unusually high homeownership rates in transition countries might appear somewhat problematic.

Whether the benefits of homeownership actually outweigh the costs, or is it more a matter of personal preferences—in the words of Gyourko (2009) “The main reason to own is because you really like your home, not because it makes you money. It doesn’t”—is definitely a topic for a very long discussion. A fact is, however, that many governments have made much effort in the last years to make people homeowners. Were these efforts successful, and what does “success” actually mean in this context? The existing body of literature about the outcomes of homeownership promoting policies turns out to be very rich. For the purpose of this article, we will only focus on policies aimed at reducing the costs of mortgage loan interest.

For many households, the costs of a mortgage loan are a significant and long-term position in the monthly expenses list. Total mortgage debt in developed countries typically ranges between 30 and 70 % of the gross domestic product (GDP), but in some countries like Denmark or the Netherlands it exceeds 100 % (DICE Database 2012). Depending on country-specific legal regulations, government support for homebuyers can be provided in different forms, for example as direct or indirect income transfers (subsidies). In the case of direct subsidies, a certain sum of money (fixed or income-related) is granted for households with the purpose of improving their housing conditions. In the case of indirect subsidies, households may deduct a part of loan interest from income tax, thereby effectively reducing the amount of tax to be paid. The social neutrality of such deductions has been questioned in the literature. Donner (2002: 84) pointed out that “if tax allowances are based on individual taxable income and the marginal taxable rate, then they become regressive, i.e. wealthier households benefit much more from them”. Such situation can be observed in the USA, where 16 % of richest taxpayers accounted for 54 % of the total value of mortgage interest deductions (as of 2003, data according to: Andrews and Sánchez 2011: 229). Alternatively, the amount of deductions might be independent from income (fixed sum). Then, they are relatively more beneficial for the less affluent households.

Subsidies and affordability: a literature overview

Housing affordability, in most general terms, is a relationship between the costs of housing, and the revenue at households’ disposal. More precisely, it “expresses the challenge each household faces in balancing the cost of its actual or potential housing, on the one hand, and its nonhousing expenditures, on the other, within the constraints of its income” (Stone 2006: 151). Most, if not all housing policies are implemented with the purpose of improving housing affordability, either directly (for example, by providing rent or mortgage subsidies) or indirectly (for example, by stimulating residential construction, which in turn should lead to lower prices). The existing literature suggests that this purpose has not always been achieved, yet further research on the matter is needed.

In particular, it has been argued by many authors that homeownership promoting policies do not necessarily lead to better housing affordability. One of the more interesting cases is Taiwan, which has one of the highest ownership rates in the world. The Taiwanese government initiated a set of pro-ownership policies in the 1970s. One of the policies was mortgage loan subsidies. However, Bourassa and Peng (2011) investigated the situation in Taiwan and concluded that there seems to be no relationship between subsidies and homeownership rate. The housing market situation was somewhat confusing, because “house prices are high relative to household incomes in most Taiwanese cities, [but] the vast majority of households still choose to buy a house” (ibid., page 2891). This phenomenon, as they argue, can be explained by expected price inflation, low taxes on owner-occupied housing, and limited options in the rental sector.

There is also some evidence suggesting that subsidies or tax deductions might even have a negative effect on housing affordability. A large study of OECD countries has shown that—contrary to the political intentions—generous tax reliefs on mortgage debt were probably capitalized into higher housing prices (Andrews and Sánchez 2011), while the main causes of increasing homeownership rates in OECD countries turned out to be: population aging, increasing incomes and more liberal rules of mortgage financing. Instead of promoting homeownership, mortgage subsidies could make it financially unfeasible for lower income households. Other authors seem to arrive at the same conclusion. Berger et al. (2000: 1999), who investigated a dataset from Sweden, conclude that “our estimates indicate very clearly that interest subsidies are capitalized into house prices”. Subsidies (or tax deductions) might also lead to a higher level of mortgage interest, as in the case of the U.S. mortgage interest deduction. It is the largest housing-related subsidy in the USA, which reduces tax revenues by more than 100 billion U.S. dollars each year (Hanson 2012). From this sum, the lenders capture between 9 and 17 % in the form of higher interest rates (ibid.). There is also a large number of other critical studies, including those of Benchetrit and Czamanski (2009), who demonstrate that government subsidies have incurred high costs for disadvantaged groups in Israel, and Bourassa and Yin (2008), who found out that mortgage interest tax deductions had a negative impact on homeownership rates among young urban adults in the USA.

The advocates of mortgage interest subsidies seem to be a minority, if the number of publications may be any indicator. One of the supporters justified his position in the following way”tax deductions on mortgage interest […] are defensible on grounds of both economic efficiency and the social benefits of homeownership” (Weicher 2000: 547). The latter argument (social benefits) assumes a priori that subsidies indeed lead to higher ownership rates. However, as indicated above, this relationship has been questioned by a number studies. Although there seems to be a wide consensus that homeownership has some important benefits (yet also some costs and risks, which should not be overseen), the literature suggests that it is quite doubtful whether government subsidies are a good way of encouraging people to become owner-occupiers.

The question we are particularly interested in this paper is the relationship between the spatial distribution of subsidized mortgage loans on the one hand, and housing affordability on the other. There have not been many studies addressing the subject from that perspective. Again, well documented research on the matter can be found mostly in the USA, which is not surprising given the large popularity of mortgage interest deductions in that country. Brady et al. (2003) found that tax deductions were substantially regionally differentiated. Both housing prices and incomes were positively associated with the number and value of deductions. Differences in housing prices explained about 40 % of variation, while differences in state and local taxes explained an additional 20 %. In this paper, we also expect to find a positive association between housing prices and incomes on the one hand, and subsidies on the other. However, as it will be argued, it is also important to investigate the relationship between the ratio (or difference) of incomes and housing costs (i.e. housing affordability), and subsidies.

Mortgage loans, subsidies and the post-socialist transition

Mortgage subsidies are a relatively new topic in the literature on housing policies in transition countries. The most probable reason for this is the fact that mortgage loans played only a marginal role in housing finances in most Central and East European (CEE) countries until the middle of the 2000s. Two-digit loan interest rates as well as insufficient income levels made mortgage loans virtually unavailable for most households. Consequently, such a policy could hardly have a significant impact on the housing sector as a whole, even in countries like Hungary, where a generous mortgage subsidy scheme was initiated already in the year 2000 (Hegedüs et al. 2011). Meanwhile, mortgage loans have become an essential instrument of housing financing in transition economies. While interest rates are still higher than those in mature markets, the relationship of mortgage debt to GDP has significantly increased in all new EU member states from the CEE region (Table 1), and this trend is very likely to continue.

The importance of mortgage-related regulations and government policies will also increase, because the condition of the mortgage market is closely linked to the overall condition of the economy, as the last financial crisis clearly demonstrated. Depending on national housing finance regulations, some countries might be more vulnerable to shocks than others. Let us consider an example from the CEE region: Hungary, with relatively liberal mortgage loan regulations, turned out to be more vulnerable than the Czech Republic, with a more restrictive system and government-sponsored incentives for housing savings (ibid.). The restrictiveness of Polish regulations and the reaction to crisis could be probably classified somewhere between these two extreme cases. Foreign currency loans started to be increasingly popular in Poland, but before foreign currency debt reached a size comparable to Hungary, more rigorous lending rules have been introduced. As of 2010, the ratio of mortgage debt to GDP in Poland was smaller than in Hungary, but higher than in the Czech Republic.

Since mortgage loans will very likely play an increasingly significant role in housing financing in CEE countries, a crucial question is how the mortgage-related government interventions can be shaped in such a way as to improve the still difficult housing situation in these countries. Possible options include different forms of mortgage loan subsidies, and in particular interest-rate subsidies and down payment subsidies. On the basis of exemplary data from Budapest and Moscow, it was demonstrated by Hegedüs et al. (2004) that the potential effects of down payment subsidies on housing affordability are more positive than these of interest-rate subsidies.

Among state interventions related to the mortgage market, one should also mention government mortgage guarantees.Footnote 3 Such guarantees have a long tradition in some countries with well-developed mortgage markets (USA, Canada, Netherlands), and they have also been introduced in some transition countries like Lithuania or Slovenia. Hegedüs et al. (2004) suggested that government mortgage guarantees might have a similar effect on affordability as down payment subsidies. Some authors argue that depending on particular regulations such guarantees might be either self-sustaining (which means that the sum of public expenditures due in the case of debtors default is balanced by the sum of insurance fees paid by debtors), or become in fact public subsidies; the USA is an example for the first case, and the Netherlands for the latter (Elsinga et al. 2009). A crucial issue in this context is the calculation of default risk, which can be particularly difficult in the still unstable CEE housing markets. At the point of writing these words, no government mortgage guarantees were provided in Poland.

The introduction of mortgage loan subsidies or guarantees might lead to a preferential treatment of home ownership, if comparable benefits are not provided for the rental market. While some CEE countries more decidedly moved in the pro-ownership direction already in the early phase of transition (Hungary, Slovakia), other (Czech Republic, Poland, Slovenia)—at least for some time—combined the support of homeownership with subsidies for rental housing (Hegedüs et al. 2011). Some of them (in particular Poland) in the following years reduced or even withdrew a large part of subsidies for the rental market, and placed more emphasis on supporting homeownership. However, one should not rule out that the policy might become more oriented towards a mixture of tenures in the following years.

Data and methods

The primary source of data for the purpose of this article was “Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego”Footnote 4 (BGK 2012). It is a state-owned bank (not to be confused with the central bank—NBP), which coordinates the process of granting subsidies from the public side. The available data include two variables, namely the number and value of subsidized mortgage loans. At the point of writing these words it was only possible to say how many subsidized loan agreements were signed, and what was their value, but it was not possible to calculate the total sum of public support involved in the policy, because the amount of subsidies is variable [for the formula of calculating subsidies see Eq. (1) and related explanation]. Mortgage loan subsidies data refer to the status on 31 December 2012.

Data are spatially disaggregated and available for provinces (regions) and regional capital cities. The provinces (pol. województwa) are self-governing regions, which are the largest units of administrative division in Poland; they are classified as NUTS-2 level in EUROSTAT nomenclature. Provinces vary in size between one and five million inhabitants. There are 18 regional capitals, as two regions have two capitals each.Footnote 5 The smallest city among the regional capitals has just a little more than 100,000 inhabitants, while the largest one (the capital of Poland) has a population of approximately 1.7 million. It should also be clarified that, in accordance with data availability, each time the terms “region” or “province” are used in the following part of the article, they refer to that part that surrounds the capital city, not the whole administrative unit. So, data for provinces exclude regional capitals, although they are obviously a part of provinces in administrative sense.

Another important source of data was the Central Statistical Office of Poland, and in particular a report about property transactions, which included housing price data (CSO 2012), as well as the Local Data Bank (CSO 2013). The latter is an on-line service providing access to a rich collection of spatially disaggregated socio-economic data; it includes, among others, data on salaries and tax revenues, which have been used in this article. Data on the number and structure of mortgage loans was drawn from the Polish Banks Association (PBA 2013).

Additional remarks need to be made with regard to the housing price data. Although a free property market has been developing in Poland over the last two decades, the availability of transaction data still poses a serious problem. The statistical office started publishing data on housing transactions a couple of years ago, but there were problems with data completeness and accuracy. In fact, 2011 was the first year when relatively complete and spatially disaggregated were made available to the public. Before that, it was a common practice to conduct investigations based on offers published by the developers, which could obviously give misleading results. Housing price data used in this paper were calculated based on a large set including thousands of market transactions. One disadvantage is that the data do not include single-family homes. However, at this scale of spatial aggregation it should not be considered as a serious problem.

The key part of this paper is an analysis of spatial differentiation of two phenomena. The first of them is government-sponsored subsidization of mortgage loans, which is an example of state interventionism in the housing market. The latter is housing affordability, which is a synthetic measure of supply/demand relations in the housing market. There is a two-sided relationship between the two phenomena, since the income/price relations are the framework in which various government policies are implemented, but these in turn might have an effect on housing affordability (not always the expected one, though).

In principle, any policy that involves some public spending can be characterized using two basic parameters: the participation rate (let us call it the “horizontal dimension” of a policy), and the amount of support granted per participant (i.e. the “vertical dimension”). Available data allowed us to measure both the “horizontal” and the “vertical” dimension of “Family’s own home” policy. An indicator of the participation rate was the number of subsidized loans per 100,000 inhabitants. Relative values were used in order to compare territorial units of different size. The average value of subsidized loans per one participant was an indicator of the individual amount of support. An additional measure, which combined both dimensions, was the average value of subsidized loans per 100,000 inhabitants.

Although “housing affordability” is actually a concept based on common sense, it turns out to be a little bit complicated to choose the right measure. For research and policy purposes, housing affordability is usually calculated as a ratio of household income and housing expenditures. An alternative measure has also been proposed, which is based on residual income, i.e. that part of income which is left after the housing costs are paid (Stone 2006). Yet, in this paper the “traditional” ratio approach was used, mostly because of its popularity and simplicity, as well as because of a limited availability of data. A measure of housing costs was the average dwelling price per 1 m2, based on a large sample of market transactions. The case with income was more difficult. Two alternative measures were used: the average monthly salary, and the estimated household income. Consequently, two indices of housing affordability were calculated: a salary/housing price index (SPI), and a household income/housing price index (HPI). More technical details about these indicators are provided in the respective sections of the article.

Housing situation in Poland

The overall housing situation in Poland is far from satisfactory. First of all, the number of dwellings in the housing stock is much below the average of EU member states. As of 2008, there were 345 dwellings per 1,000 inhabitants in Poland, compared to 488 in Germany, 486 in Sweden, and 429 in Hungary (Ministry of the Interior… 2010: 62). It is important to note that the availability of housing in Poland is low even compared to countries at a similar stage of development (Fig. 1). Although a majority of the housing stock meets minimum equipment standards, many dwellings offer a quality that does not correspond to modern needs (dilapidated pre-war tenement houses, prefabricated socialist blocks). There are several causes of the housing deficit, some of them of historical nature (late urbanization, war destruction). The main problem, however, is that progress in improving housing conditions after the fall of socialism has been too slow (Frąckowiak 2008).

Total dwelling stock per 1,000 inhabitants in selected EU member states (most recent available data). Source Ministry of the Interior… (2010), data for the year: Czech Republic & UK 2000, France 2006, other countries 2008

The shortage of housing has become an even more serious concern in the middle of the 2000s, when the “baby-boom” generation of the early 1980s started to enter the market. Fortunately, this coincided with general economic prosperity. Also, the legal rules of mortgage financing were quite liberal. Lenders required small down payments of 10–20 %, and in some cases even no down payment at all.Footnote 6 So, even young households with very few savings were allowed to enter the mortgage market. Moderate income levels were also not a barrier, because monthly loan payments could be reduced thanks to long financing periods (25–30 years, or even longer). On the other hand, first-time buyers were confronted with sharply rising housing prices, which in some cities increased by as much as 50–70 % only between 2006 and 2008. Many people entering the job market were not able to find a salary that would cover the increasing cost of living. Given the low level of income—the average monthly salary in Poland is below 1,000 EUR—and a two-digit unemployment rate, it is not surprising that many people have chosen to emigrate after the opening of European job markets for Polish workers.Footnote 7 There are no official data concerning the number of migrants, but according to some estimates it might be as much as about 2 million.

Similar to other post-socialist countries, Poland is characterized by a high rate of homeownership. According to the most recent data, 63 % of dwellings in Poland were owner-occupied, 12 % were rented, and 24 % were dwellings in housing cooperatives (ibidem: 64). The latter are actually functioning as owner-occupied dwellings, and in most cases they can be easily transformed into full ownership.Footnote 8 That is one of the reasons why many owner-occupiers can be found also in multifamily housing. It is an important difference in comparison to the USA, for example, where most single-family houses are owned, while most apartments are rental. In Poland, a large share of the existing multifamily stock is owner-occupied, and in the last few years a supply of new apartments for rent has practically not existed, except for social housing.

The rental housing sector is not well developed. The construction of social rental housing has been reduced in the last 20 years because of financial shortages in the public sector. At the turn of the 1990s and 2000s there was an attempt to establish a new model of social housing with a higher financial participation of tenants (pol. towarzystwa budownictwa społecznego, TBS). It was in fact one of a few innovative housing policy instruments in the post-socialist countries (Tsenkova, this volume). TBS were quite popular in several large cities and a few smaller ones, but after the government cut back the financing, the municipalities were not able to sustain this model, and the construction activity of TBS ceased very soon.Footnote 9

The private rental sector consists of a formal sector and of a substantial informal (“grey”) sector. The main cause for the large size of the informal sector are the tenant-landlord regulations, which are one of the most restrictive among the OECD countries (Andrews et al. 2011).Footnote 10 Formal rent contracts have to comply with a number of legal rules, concerning in particular rent increases and termination periods. Informal contracts are essentially not being supervised by public authorities. There are only estimates that say that ca. 5 % of formally owner-occupied dwellings are de facto rented (Ministry of the Interior… 2010: 65). At the moment, there seems to be an over-regulation of the private rental market, which discourages potential landlords, and so limits the supply for potential tenants. Also, the media have recently reported about some cases of serious violation of tenant rights, as some private landlords attempted to evict long-term tenants from old tenements houses, using practically criminal methods. The formal rules of tenant protection were of no use in these cases. Notwithstanding the fact that many rent agreements, even those informal ones, might be functioning quite well, the media coverage has definitely not improved the overall perception of rent as an insecure tenure. Since 2009 it has also been possible to sign less stringent rental contracts (so called “occasional rentals”), but this option was only available for individual landlords, and not for the institutional ones.

The access to social housing is in general very limited, while private rentals are seen mostly as a short-term option for students and young employees. In this context we should also add that the population on Poland is in about 1/3 rural, and the rental market practically does not exist in rural areas. To sum up, the rented housing sector does not offer an attractive alternative to ownership. That is one of the reasons why the desire for homeownership is strong even among groups with below-average income. Under these circumstances, a program of mortgage subsidies could be seen as a proper response to societal needs. But as previous experience shows, well-intentioned public actions do not always achieve the results they were designed for.

Regional differentiation

The spatial structure of the housing market in Poland has become increasingly differentiated since the fall of socialism. In particular, the difference between the largest cities and the rest of the country has greatly increased. The principal reason are employment opportunities. After 1990, a lion’s share of new investments, either foreign or domestic, has been concentrated in few urban centers. These include: in the first line Warsaw, the national capital, followed by strong regional centers like Cracow, Wrocław, Poznań and Gdańsk. Regional capitals are usually also strong academic centers, benefiting from the popularity of higher education among the young people. Many graduates do not return home, but rather start a career in the city, which means increased demand for housing. So, each of the above mentioned cities has been characterized in the last years by high levels of residential construction, but also very high prices. Suburbanization processes have also been developing very intensively around the top-cities.

The overall spatial pattern of economic development in Poland shows some characteristic features. On the one hand there is a kind of east/west division, with western parts of country being in general more urbanized, more industrialized and more affluent than their eastern counterparts. Regions located on eastern peripheries (Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Podlaskie, Lubelskie, Podkarpackie and Świętokrzyskie) are commonly referred to as the “eastern wall” (pol. ściana wschodnia). They are of predominantly rural character, with a domination of small-scale private agriculture. On the other hand, also in the western part of Poland some problematic areas can be found. These include in particular regions in which large state-owned agricultural companies (pol. państwowe gospodarstwa rolne, PGR) were established under socialism. After 1990 the state was no longer willing to continue production in these farms, and many former workers became unemployed without good opportunities for a new job. Such structural problems prevail for example in large parts of the province of Zachodniopomorskie.

“Family’s own home”: subsidized mortgage loans in Poland

The promotion of homeownership in Poland does not have a long history. Under socialism the construction of private single-family houses was tolerated, but by no means encouraged by the government. Apartment houses, on the other hand, were a domain of state-controlled cooperatives, and no private initiative was allowed there. The first explicitly homeownership promoting policy introduced in post-socialist Poland—except for privatization programs in the cooperative and municipal stock—was the mortgage interest tax deduction.Footnote 11 Interestingly, this de facto tax reduction was enacted by a left-wing government, shortly after coming into power in the year 2001. According to this law, mortgage interest may be deducted from income subject to taxation, up to a certain limit. This policy was dropped in 2006, when a new policy (“Family’s own home”) was introduced. However, households who signed a loan agreement in the period between 2002 and 2006 are still allowed to deduct interest from income.

In 2005 a right-wing party formed the new government in Poland. One of the key elements of the ruling party’s program was a pro-family policy. Therefore, mortgage interest subsidies were proposed as a way of helping young families to buy the first own dwelling. It is important to note that this pro-family aspect was the main policy rationale at the early stage. Other arguments, which are typically used to justify such government interventions (increasing residential construction, for example) seemed to be less important at that point. That changed a couple of years later, when a liberal party took over the political power and modified the policy’s rules. The target group was extended to include not only families but also single persons at an age below 35 (weakening the pro-family aspect), and differentiating price ceilings for primary and secondary market transactions in order to treat new housing preferably. However, just 1 year after these changes came into force the policy was terminated, mostly because it was simply getting to expensive for the public budget to handle.

General rules

The original rules of “Family’s own home” policy were the following. The target group were—not surprisingly—the families, defined for this purpose as married couples or single parents. Since the aim of government intervention was to support first-time buyers, the applicant could not already be an owner, nor even a tenant (rental contract had to be terminated once a loan agreement has been signed). Please note that there was no income limit for participants. Instead, in order to avoid spending public money on very expensive housing, price and dwelling size limits were specified. The size ceiling for apartments was equal to 75 m2, while in the case of single-family houses the ceiling was nearly twice that large—140 m2. However, the maximum subsidized area was lower: 50 or 70 m2, respectively. So, if a subsidized loan was granted for a 70 m2 apartment, the subsidies were paid for that proportion of the total loan sum that corresponded to 50 m2, while the remaining 20 m2 had to be financed on normal terms. Down payment requirements were the same as for all other mortgage loans, so in some cases subsidized mortgage loan could cover up to 100 % of the total dwelling price, of course up to the limits specified above. In practice, the most important criterion were the price ceilings, which were spatially differentiated. In the regional capitals it was possible to receive subsidies for more expensive housing, although particularly in the earlier years the ceilings were much lower than market prices. In the rest of country’s territory the ceilings were also regionally differentiated, but generally lower than in the regional capitals.

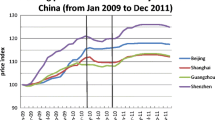

Policy rules were changed several times (Table 2). Price ceilings, initially equal to the replacement cost,Footnote 12 soon turned out to be much below the market level, so in the first months after the policy start on 1st January 2007 very few loan agreements were signed. Critical comments about the policy’s ineffectiveness could already be heard at that time. As the decision makers realized their mistake, the ceilings were raised just half a year after the policy had been initiated, and for the second time in the following year. These were rather small changes, but their effects were significant, because the number of participants increased rapidly (Fig. 1). The most important change in policy rules, which practically defined new directions of government intervention, was undertaken by a new government in the year 2011. The target group was extended to include also non-married and childless persons (singles), however they were only eligible to get subsidies for relatively small apartments. At the same time price ceilings were substantially reduced, especially for secondary market transactions.

Government subsidies were provided only for mortgage loans taken in the national currency, i.e. Polish złoty (PLN). Subsidies were granted for the first 8 years of mortgage loan repayment period, which usually lasts between 20 and 30 years. The monthly amount of the subsidy (S) was calculated in the following way:

- RP:

-

Remaining loan principal to be paid

- AMI:

-

Assumed mortgage loan interest rate, equal to the average 3-month WIBORFootnote 13 from the last 3 months, plus two percentage points

In order to understand how generous the subsidy actually was, let us make an exemplary calculation. Assume that the borrowed sum is equal to 250,000 PLN, interest rate amounts to 5 %, the repayment period is 25 years, and there is no down payment. Then, with equal rates, monthly payments without subsidies would amount to 1,461 PLN. However, if the government mortgage interest subsidy was granted, then, assuming WIBOR = 4 %, the first rate would be lowered by the following sum:

With mortgage interest subsidy the household would pay only 836 PLN in the first month. In the equal rates system, the principal decreases slowly in the initial period because of large interest payments. So, the financial support of the government, provided during the first 8 years of repayment, comes exactly when it is most needed. Although the monthly amount of subsidies declines as fewer principal remains to be paid, the support of the government substantially decreases households’ mortgage-related payments for quite a long time. Alternatively, subsidized mortgage loans might be also repaid using decreasing rates (constant capital rate + variable interest rate), instead of constant rates. However, with that option a household would be generally worse off, because the remaining principal would be decreasing faster, and so would be the subsidies calculated on its basis. An open question is whether some beneficiaries encounter financial liquidity problems when their monthly loan payments sharply increase once the 8-year subsidization period is over.

Policy outcomes

It was not an easy way to get the families into their homes, to paraphrase the policy’s nickname. At the beginning the subsidies did not enjoy much popularity because the price ceilings were set much below the level of market prices. Although the ceilings were raised by 30 % just a couple of months after the policy was started, only a small number of loan agreements were signed in 2007 and 2008. Voices of criticism that first appeared already in the first months after the start were becoming more widespread. There was a joke at that time that referred to one of the policy requirements. Namely, it was suggested that the number of fictional marriages started to rise because young people wanted to utilize the subsidies. However, modified rules eventually brought an effect after some time, and in 2009 both the number and the value of subsidized mortgage loans significantly increased, and that trend continued until 2011 (Fig. 2). Advertisements of “dwellings with a subsidy” appeared on the streets and in the media, as the developers revealed their expectations that government’s new policy would bring a stimulus to the housing market, which already started to slow down a little bit after a period of rapid growth. These expectations, as shown in the following part, were only partly fulfilled.

In the last year the participation declined just a little bit, although the eligibility criteria were much more restrictive. A total number of about 180,000 mortgage loans were subsidized in the years 2007–2012, and the total value of loans reached nearly 33 billions PLN (ca. 8 billions EUR). In a period when the subsidies enjoyed the most popularity (2010–2012) subsidized mortgage loans made up about one-fifth of the value of all new mortgage loans (17 % in 2010, 20 % in 2012, source: PBA 2013). To sum up, the subsidies were becoming increasingly popular from year to year, but paradoxically this success soon turned out to be a problem. Even if the policy was relatively small compared to other public expenditures, in times of high public debt any savings are very welcome. In the course of financial cuts the government decided first to reduce the price ceilings, and finally, to terminate the whole policy. Since then, subsidized loan agreements have no longer been signed. Of course, those households that have already signed an agreement continue to receive government support in the form of monthly subsidies.

Relations to housing construction, prices and mortgage interest

It is difficult to say anything precise about the temporal relations between subsidies and housing construction, prices and mortgage interest because of lack of sufficient data. In particular, comparable time-series data on housing prices and mortgage interest rates are missing. However, some conclusions can be drawn even from the limited existing dataset. Evidence suggests that the stimulating effect of subsidies on residential construction was rather weak, if there was any. The number of housing construction permits shows a positive trend in the prosperity years between 2002 and 2007 (Fig. 3). A particularly notable increase in permitting occurred between 2006 and 2007. In that year, the number of permissions was the highest in the whole post-socialist period. In 2008 permitting declined slightly, but still remained on a high level. The high number of permits was primarily a cause of the overall economic prosperity. Yet, we may suppose that there was some policy influence. Let us call it for this purpose an “expectation effect”. Namely, as the government announced a new policy in 2006, developers might have applied for more building permits in the following 2 years than they would normally do, as they expected an increase in demand for owner-occupied housing.

In 2009 the number of permits dropped and a negative trend continued also in the next years, despite a small correction in 2011. Polish economy avoided a recession as strong as in some other European countries, but the overall economic situation worsened. Another reason for decreasing permitting was an oversupply of housing projects, which were started by optimistic developers already in the prosperity phase. The number of permissions declined between 2008 and 2012 by about a half, and particularly in the years when most subsidies were granted (2010–2012) the permitting was at a very low level. That surprising result can be explained in the following way. A decisive criterion of the “Family’s own home policy” were the dwellings’ price ceilings. The ceilings were initially set at the same level for primary market and secondary market transactions. Because of lower prices, old dwellings more often met the policy’s requirements than the new ones. Consequently, despite slightly declining tendency, a majority of participants utilized the subsidies for secondary market transactions (Table 3). The share of primary market transactions was increasing from year to year, but it has never reached more than one-third of the sum. In general, only 26 % of all subsidized loans were provided to households buying new dwellings. About 18 % of subsidized loans were utilized for the construction of single family homes by private persons.Footnote 14 This share was relatively constant over time.

In autumn 2011 the government tried to counteract by differentiating price ceilings for the secondary market and the primary market. In both cases the ceilings were reduced, but new dwellings were treated preferably. That brought some effect, as the number of subsidies granted for new dwellings in 2012 for the first and only time exceeded 30 %. If such policy rules were in force for a longer time, they could potentially have some stimulating effect on residential construction, but on 31 December 2012 the “Family’s own home” policy was terminated. However, we may hypothesize that the preferential treatment of new housing in the final phase helped to reduce the oversupply in housing market, which was a late effect of the prosperity years.

Another interesting question is whether the subsidies had some effect on housing prices. Theoretically, mortgage loan subsidies make owner-occupied housing more affordable in comparison to rental housing. So, ceteris paribus, the demand on homeownership should increase, while rising demand combined with inelastic supply may lead to higher housing prices. There is some empirical evidence of the capitalization of mortgage subsidies into prices (Andrews and Sánchez 2011; Berger et al. 2000). Can such a relationship be found also in the case of “Family’s own home”? As mentioned above, a substantial problem is the availability of data. Existing data sources let us conclude the following. Changes in the level of housing prices in Poland in the last decade can be best described using an s-shaped curve (Fig. 4). Until 2006, prices were increasing only slightly, but then the increases suddenly gained momentum. Particularly large increases took place in the years 2007/2008, so in a period when the subsidies did not enjoy much popularity. In later years the level of prices stabilized, and even small decreases took place. A set of factors influenced the development of housing prices in that period. Firstly, the rules of mortgage financing were liberal (low down payment requirements, long financing periods), which significantly increased the number of potential homebuyers. Also, at least to some extent, housing prices were bidden up by speculative buyers who expected further increases. The whole process was functioning as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, but of course this had to end at some point. Fortunately, a spectacular burst of the “housing bubble” was avoided, but price increases stopped and even some reductions occurred. The prosperity caused some developers to be too optimistic, and they were eventually left with a large stock of unsold dwellings. An oversupply occurred, which in turn caused developers to cut their price expectations down.

We could also hypothesize that the subsidies had an adverse effect, that is, they led to a lower level of prices in comparison to the no-subsidy scenario. That hypothesis is difficult to verify in empirical terms. Perhaps some developers adjusted their price offers to the price ceilings. But it is not obvious in which direction this adjustment actually took place. In the first 2 years of policy implementation it was difficult to find dwellings at prices that met the eligibility criteria. So, perhaps developers were willing to sell somewhat cheaper. As the prices declined, the meanwhile increased price ceilings turned out to be much closer to the market level of prices. In that situation, government support might have curbed the decrease of housing prices.

It has been argued by Hanson (2012) that subsidized mortgage loans in the USA were characterized by a higher interest rate, meaning that a part of government support directly benefited the lenders. Whether such a problem also occurred in Poland, is difficult to verify in empirical terms because of limited data availability. But the subsidies probably had some effect on the development of mortgage market and the structure of mortgage debt. In the 1990s, mortgage loans were not a common way of housing financing in Poland. In 1998, total mortgage debt amounted to just 1.5 % of GDP. In 2010, the ratio was already 19.1 % (DICE Database 2012). A lion’s share of that increase fell on loans in foreign currencies, particularly Swiss francs (CHF) and euro. Despite risks related to the variable exchange rate, such loans started to be increasingly popular in the middle of 2000s because of a substantially lower interest rate in comparison to loans in the national currency, Polish złoty (PLN). Being aware that a high share of foreign currency loans might be a threat for the economic stability of a country (see the casus of Hungary, for example), in 2008 the financial market supervising board decided to apply a more restrictive policy, discouraging banks from issuing these loans.

That change coincided in time with the rising popularity of “Family’s own home” policy. According to the law, subsidized loans could be issued only in the national currency. Since 2009, the structure of new mortgage loans significantly changed. Polish złoty became the most popular currency, and the share of foreign currency loans declined. As mentioned above, that structural change in the mortgage loan market was primarily a consequence of more restrictive financial market regulations. However, the subsidies generally made borrowing in the national currency financially more attractive. Perhaps it helped—to some extent—to avoid problems with foreign currency mortgage loans like those which occurred in Croatia or Hungary (Hegedüs et al. 2011), and to stabilize the mortgage market in a difficult time of financial crisis.

Spatial differentiation of subsidized mortgage loans

Spatial differentiation of subsidized mortgage loans in Poland shows some interesting features. Both the participation rate and the average loan value per participant were greatly variable among the investigated cities and regions. Also, both variables were not necessarily closely linked to each other. For example, in some areas the participation rate was moderate, but the participants received on average very high subsidized loans (Table 4).

The average participation rate in “Family’s own home” policy amounted to 471 subsidized loans per 100,000 inhabitants. Participation was generally higher in regional capitals than in the rest of the country. In regional capitals, the rate usually fell in the range between 600 and 1000 loans per 100,000 inhabitants, while in the provinces (excluding capitals) it varied between 300 and 500 loans per 100,000 residents. However, it were not necessarily—as one could expect—the largest cities that were characterized by the highest participation. Rather, the policy was mostly widespread in medium-sized cities (between 100,000 and 400,000 residents), where the participation rate approached, or even exceeded 1,000 subsidized loans per 100,000 inhabitants. There seem to be two factors that determined the participation rate: the overall dynamics of the housing market, and the price ceilings that defined eligibility criteria for “Family’s own home” policy. Housing markets in cities are more dynamic than in rural areas, which implies that the number of transactions—and consequently, also the number of mortgage loan agreements—is higher. However, participation rates found in the largest cities turned out to be somewhat lower than expected. The main reason for this was the very high level of housing prices in cities like Warsaw or Cracow, which effectively reduced the number of dwellings eligible for support. In other words, it was difficult to find a dwelling that would both satisfy households’ needs and meet the policy’s eligibility criteria. Had the price ceilings been even slightly more generous, the participation rate in the largest cities would be probably much higher.

The average value of subsidized mortgage loans in the 2007–2012 period amounted to 182,000 PLN, which is approximately 40,000 EUR. For a comparison, the average value of all new issued loans (subsidized and non-subsidized) in the years 2010–2012 varied between 200,000 and 210,000 PLN (PBA 2013). Again, a gap between regional capitals and the rest of country was clearly visible. In that case, however, it was in large part a consequence of an outstanding position of Warsaw. An average subsidized loan value exceeding 300,000 PLN reflects the unique character of Warsaw’s housing market, which has drifted much away, especially in the last few years, from the other large cities, in terms of housing prices and rents. Strong regional centers like Cracow, Wrocław, Poznań and Gdańsk have formed what may be called a “chasing group”. In these cities the average loan values fell in the range between 200,000 and 250,000 PLN, which situated them much behind Warsaw, but clearly ahead of all the rest. That result confirms that there are at the moment several high-demand urban housing markets in Poland, yet the national capital is by far the most expensive among them. In the case of smaller regional capitals subsidized loan values typically varied between 150,000 and 200,000 PLN. Most provinces also fell within this range.

The results of this part of the study can be summarized in the following way. An important observation is that a lion’s share of government support was directed towards regional capitals. Eighteen cities that account for just 20 % of the total population of Poland received almost one-third of all subsidized loans. Consequently, regional cities’ inhabitants were two times more likely to benefit from “Family’s own home” policy than the rest of population. The dominance of regional capitals was even more evident when the loan value was considered (Fig. 5). Among provinces, these located in the western part of the country generally had a higher participation rate than those from the east (Fig. 6). One of the reasons might be differences in regional economic development, as the western part of Poland is generally more affluent than the eastern part, which is sometimes referred to as the “eastern wall” (pol. ściana wschodnia”). Another explanation might be cultural reasons, as Poles from the southern and eastern part of the country (which belonged to Austria-Hungary and Russia before the World War I) are believed to be more conservative in their views than their counterparts from the northern and western part (which belonged to Prussia). So, they might rely more on other than mortgage ways of housing financing (family loans, for example). The southern and eastern parts of Poland also have a higher share of rural population.

In general, we may conclude that the residents of more affluent areas were more likely to benefit from public support, and they also received more funding per capita. The value of subsidized loans per 100,000 inhabitants was nearly three times greater in regional capitals than in other areas. That large difference was a consequence of both higher participation and average loan value. Residents of cities like Warsaw, Cracow and Wrocław were—despite price ceilings, which reduced the participation rate a little bit—the main beneficiaries of “Family’s own home” policy. At the other end were the residents of “eastern wall” provinces (Lubelskie, Podlaskie, Podkarpackie, Świętokrzyskie), who not only participated less frequently, but also received less funding per capita.

An interesting question is whether the subsidies had some relationship to the suburbanization processes. Unfortunately, due to lack of more spatially disaggregated data, only a partial answer can be given in that case. Provinces surrounding the largest cities had both high participation rates and per capita loan values. This result suggests that a large share of subsidized mortgage loans was indeed utilized in for financing of suburban housing. More accurate data would be needed to make more definite statements about this relationship.

To sum up, large cities were the main beneficiaries of government-subsidized mortgage loans. An important question is whether large cities are actually less, or more affordable than other areas, and what are the differences in housing affordability among the provinces? These questions will be addressed in the following section.

Housing affordability

The affordability of housing, in most general terms, can be defined as a kind of relationship between housing-related expenditures and wealth (Bogdon and Can 1997; Quigley and Raphael 2004; Stone 2006). Spatial differences in housing affordability are of crucial importance for both society and economy, yet they are rarely fully acknowledged. A deficit of knowledge in this field is a particular problem for developing countries like Poland, where the availability of reliable data about housing costs and household incomes is still far from satisfactory. Spatial differentiation of housing affordability is also very important from the point of view of policy-making. If we agree that one of the fundamental functions of the state is to provide equal opportunities, one would expect more government support to be directed towards areas where the citizens find it more difficult to meet their housing needs.

As far as the author knows, this paper is the first one which aims to investigate the relationship between the spatial differentiation of subsidized mortgage loans, and that of housing affordability. There have been some studies that investigated how the housing prices (which are the most common indicator of housing costs) and incomes were related to the regional differentiation of subsidies (for example Brady et al. 2003). In this paper, however, we are interested not only in housing prices and incomes separately, but also (or perhaps even more) in the relationship between them.

This relationship, as stated above, may be called housing affordability. An important question is how to define this phenomenon in operative terms on the basis of the available data. In Poland, the most common indicator of housing affordability is a ratio of the average monthly salary to the average housing price per 1 m2. The main advantage of this measure is its simplicity. It can quickly be calculated on the basis of readily available data, as both regionally-differentiated monthly salaries and housing prices are included in official statistics, the latter however have been added very recently. The salary/price index is employed as one of the indicators in the following section of the article. However, monthly salary is a convenient measure of income, but not necessarily the most accurate one. Therefore, an alternative measure of income is also proposed, which is calculated on the basis of personal income tax (PIT) data.

Housing prices

As was already mentioned, a large share of housing demand in Poland is focused on a few large urban agglomerations. Housing price data reflect this fact very well. The highest housing prices in Poland were found in Warsaw, the national capital, where the average transaction price amounted to 7,900 PLN per 1 m2, which is nearly 2,000 EUR (data for the year 2011).Footnote 15 Rank two, well ahead of the other cities, was occupied by Cracow, the historical capital and the most popular foreign-tourist destination of Poland. In that case, prices were probably driven up by apartments situated in the medieval old town. In general, the level of housing prices was positively associated with city size, but there were also some notable exceptions. An interesting case is Łódź, the third-largest city in Poland, and once an important center of textile industry (the so-called “Polish Manchester”). The city has lost many jobs during the transition, and the number of residents has declined by more than 100,000. Consequently, demand for housing is much lower than in other large cities, and dwellings are much less expensive than one would expect in a city of that size.

Housing prices in the provinces were generally lower than in the regional capitals, but there was also a significant spatial differentiation. High prices in regions surrounding the largest cities: Mazowieckie (Warsaw), Małopolskie (Cracow), Wielkopolskie (Poznań), Pomorskie (Gdańsk) and Zachodniopomorskie (Szczecin) reflect the increasing importance of suburbanization processes. Also, the last two are seaside regions, where the average prices were driven up by expensive apartments with sea view. Less expensive housing could be found in the peripheral parts of Poland, eastern and western alike.

Salary/housing price index (SPI)

Average monthly salary is a basic indicator of personal wealth in many countries, and by far the most popular one in Poland. However, one should use these data with some caution. By definition, salary data include only income from labor, and not from capital nor rent. Moreover, in Poland only salaries paid by companies with at least 10 employees are included in public statistics. These limitations cause the data to be biased in some way, and during the interpretation one should have the potential bias in mind.

As for 2011, the average monthly salary in regional capitals amounted to 3,800 PLN (ca. 900 EUR), while in the rest of country it was equal to 3,200 PLN. Looking at the data more precisely allows us to conclude that the statistics are indeed biased in several ways. Firstly, the data for cities and provinces which are hosting large industrial plants are overestimated. An extreme example of this is the city of Katowice, the largest center of heavy industry in Poland, which boasted a surprisingly high average salary (5,000 PLN). Salaries paid to industrial employees raised the average value even ahead of Warsaw (4,900 PLN). However, it would be misleading to argue that people in Katowice are on average better-off than Warsaw residents. In the capital, there is a number of people who receive a significant share of their income in other-than-salary forms, like rents or income from self-employment. Incomes from agriculture are also not included in the salary statistics.

For the purpose of this article, the ratio of the average monthly salary by the average housing price will be called a salary/housing price index (SPI). The formula for SPI is the following:

where:

- AS:

-

Average monthly salary

- HP:

-

Average housing price per m2

As already mentioned, SPI is a simple and convenient measure. It allows us to quickly answer questions like “How many monthly salaries do I need to afford a 60 m2 dwelling?” The spatial differentiation of SPI values suggests that housing was generally less affordable in regional capitals than in other areas. While in most provinces the value of the index was larger than one, in most regional capitals it fell below unity. There were some exceptions, however: in Katowice the average salary was sufficient to buy almost 1.5 m2 of dwelling space, making it by far the most affordable city, at least as far as official salary data are considered. In terms of SPI, housing was least affordable in large cities like Cracow, Warsaw and Wrocław, while in Poznań and Gdańsk it was somewhat easier to meet households’ housing needs. Pomorskie (Pomerania) was the least affordable province, a fact that can probably be explained by high prices of sea side apartments. Paradoxically, housing affordability in that province was worse than in its capital (Gdańsk). The regional differentiation of SPI has generally not reflected the east–west division of Poland. Regions with a high share of industry (Dolnośląskie, Śląskie) were most affordable in terms of SPI.

Household income/housing price index (HPI)

Measuring wealth using salaries is quite a convenient technique, but not necessarily the most accurate one. It is quite obvious that a large share of the working populations is self-employed or working in small companies, so the data on salaries are strongly biased. An alternative way is to use the average household income. Since such data are not available in official statistics in Poland, it has been calculated for the purpose of this article on the basis of personal income tax (PIT) data. According to law, each city or municipality in Poland receives a fixed percentage share of PIT paid by its registered inhabitants. So, it is possible to estimate how much tax was paid by residents, and consequently how much income was subject to taxation (at some level of precision, of course). Tax data have some important advantages in comparison to salary data. The definition of “income” for tax purposes is relatively broad. It includes not only salaries, but also social transfers (pensions), rents, stock exchange profits, and revenues from self-employment. So, these data provide a better approximation of private wealth than salaries, which are the most common indicator used for this purpose.

In order to calculate household income on the basis of income tax data, some additional parameters had to be specified. They included: the share of income tax received by municipalities, the effective rate of tax paid on income, the average household size, and a correction parameter for non-taxed income. The values of the parameters were set arbitrarily, but in accordance with the available knowledge. Based on the tax law, it was assumed that regional capitals received a 50 % share of income tax, and other municipalities 40 %.Footnote 16 The effective rate of tax paid on income was assumed at 15 % level.Footnote 17 Average household size in Poland as of 2011, based on EUROSTAT data, was 2.8 persons.Footnote 18 Since households in cities are typically smaller, an average size of 2.5 persons was assumed in regional capitals, and 3.0 persons in provinces. The correction parameter for non-taxed income was set at 10 % for regional capitals and 30 % for provinces. Please note that we have no data about illegal avoidance of taxation. So, the difference in parameter values only accounts for the fact that persons employed in agriculture are legally exempt from PIT. Also, being aware of the regional differentiation of Poland, we assumed that due to a predominantly urban character of the province of Śląskie (Silesia), the same parameter values as for regional capitals should be applied in that case.

The formula for the estimated annual household income (HI) was the following:

where:

- PIT:

-

Total per capita revenue from PIT paid by residents, PIT = MR/MS

- MR:

-

Municipal per capita revenue from PIT,

- MS:

-

Share of PIT received by municipalities (0.4 or 0.5)

- TR:

-

Effective tax rate (0.15)

- HS:

-

Average household size (2.5 or 3.0 persons),

- NTC:

-

Correction parameter for non-taxed income (0.1 or 0.3)

and, consequently, for the monthly household income (MHI):

An important observation is that the variation of MHI was greater than the variation of salaries. Average estimated household income in regional capitals was about 30 % higher than in other areas, while in the case of salaries the gap was equal to about 20 %. Of course, it is a disputable question, which indicator is a better measure of wealth. In the author’s opinion, the estimated household income, calculated on the basis of tax revenues is a more accurate approximation of the actual spatial distribution of private wealth in Poland. Tax data seem to be less biased by factors like heavy-industry than salaries data. Warsaw had the highest estimated monthly household income (6,200 PLN), well ahead of Poznań (3,900 PLN) and the other large cities. The city of Katowice, which occupied the first rank in the classification of salaries, took the third place in this case, with an average income level very similar to Cracow and Wrocław (3,700 PLN). High values of the estimated average household income were also found in provinces surrounding the largest cities: Mazowieckie (Mazovia), Pomorskie, Dolnośląskie and Wielkopolskie. On the contrary, provinces situated at Poland’s eastern border were characterized by lowest income levels, falling in the range between 1,800 and 2,100 PLN. This spatial pattern corresponds quite well to the regional differentiation of economic prosperity measured in terms of other indicators, like the gross domestic product (GDP).

It is proposed to call the ratio of household income to housing price a household income/housing price index (HPI). The formula is analogous to the formula of SPI:

symbols as in Eqs. (2) and (4).

Spatial differentiation of HPI was slightly different than that of SPI. As in the previous case, medium-sized cities were generally more affordable than the largest ones. But the difference between the western and eastern part of the country was clearly visible. While households in the province of Dolnośląskie (situated at the border with Germany and Czech Republic) could buy on average 1.2 m2 dwelling space for an average income, their counterparts in Lubelskie (at the border with the Ukraine and Belarus) could afford only a half of that. Comparing housing affordability measured in terms of the salary/price index, and that measured in terms of HPI, led us to an interesting observation. In the first case, regional capitals were on average about 25 % less affordable than the rest of the country. In the latter case, the gap between regional capitals and regions was narrower. So, when not the salary, but estimated household income was a measure of wealth, regional cities turned out to be only slightly less affordable than other areas (Fig. 7). Of course, there were quite large differences between more and less affordable cities and regions. But on average, the regional capitals and regions were not that much far away from each other. Even accounting for some inaccuracy in assumed parameter values, it can be concluded that the disparities were not as large as the salaries data would suggest. Detailed data on housing affordability in particular cities and regions are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 8.

For those who were familiar with the situation on the Polish property market in the last years, the above conclusion can be somewhat confusing. In the period between 2006 and 2008 housing prices in the largest cities had increased almost twofold. Because this growth was not paralleled by a similar increase in earnings, the affordability of housing in cities declined. At that time the difference in housing affordability between regional capitals and regions was probably grater. However, in the following years the tendencies were reversed, and incomes were rising faster than prices. The gap between regional capitals and regions narrowed. In fact, it would be quite problematic if a large disparity existed in the long term, because it would severely impede the economic development of cities.

Subsidized loans and housing affordability

In the previous sections of this article we investigated the spatial differentiation of subsidized mortgage loans and housing affordability. The purpose of this section is to find possible associations between the two phenomena. They key question is: how was the spatial distribution of government support linked to the affordability of housing? In order to answer this question, statistical correlations were calculated using the Pearson’s r coefficient. Correlations were calculated for the whole dataset, and also for the regional capitals and regions separately (Table 6).

Before we move to the interpretation of our results, one technical remark should be made. Statistical significance is a tricky issue, particularly when the number of observations is low, as in this case. When using statistical tests, one should always be aware of the risk of omitting associations between variables that indeed exist, or misleadingly reporting unrelated phenomena as correlated with each other. That risk is particularly high when sample size is relatively small. So, the results should be treated with caution. But some conclusions may be drawn even from this limited dataset.

As already mentioned in the methodological section, it was assumed that each government support policy can be measured in two “dimensions”. The “horizontal” dimension is the participation rate, which indicates how many people benefited from the policy. The “vertical” dimension is the amount of support granted per participant. Consequently, the variables in the first column of Table 6 can be interpreted in the following way. The number of subsidized loans per 100,000 residents is the horizontal dimension, while the average value of a subsidized loan is the vertical one. The value of subsidized loans per 100,000 residents is a synthetic measure, which indicates the total amount of government support.

Participation rate was positively associated with housing prices and estimated household incomes (not with salaries), but the correlation was only moderate. That relationship held for the whole dataset (regional capitals & provinces), and also for the provinces alone. In the case of regional capitals, the correlations were statistically not significant, yet—what is interesting—negative. These results mean that the residents of regional capitals, who in general received higher incomes and paid higher prices than their counterparts in the provinces, were more likely to participate. So were the residents of the more affluent (i.e. western and northern) provinces in comparison to the less affluent ones (southern and eastern). But the same was not true for the regional capitals. Participation rate in cities like Warsaw or Cracow, where demand for housing is very high, was lower than in medium-sized cities. This is because of policy price ceilings, which were set much below the market level of housing prices in these cities.

Comparing the two measures of housing affordability, we found that both were negatively associated with participation rate, but only in the case of SPI was the correlation significant. That association only existed in the whole dataset, whereas when regional capitals and provinces were treated separately, no correlation between the number of subsidized loans and SPI was found. In other words, regional capitals were in general substantially less affordable in terms of SPI than provinces, and they had a higher participation rate. Differences among regional capitals and provinces were of no importance in this context. However, in the case of HPI, the participation rate was indeed higher in more affluent provinces, but not in more affluent regional capitals.

This result might possibly indicate a weak point of mortgage loan subsidies from the social perspective. The provinces, where households find it more difficult to meet their housing needs, were not more—as one would expect—but in fact less likely to receive subsidized mortgage loans. This problem has a certain geographical dimension. Public support was utilized in a very limited scope in Poland’s eastern peripheries (the so-called “eastern wall”), where the affordability of housing was poor. A relatively low number of households in that part of country benefited from subsidized mortgage loans. The main reason were probably low incomes, which prohibited many households from applying for mortgage financing. Also, these areas are predominantly rural, so—unlike in cities—people might choose other ways of financing their housing needs than mortgage. For example, a plot for construction might be granted by the relatives, and the construction itself might be done with own work input.