Abstract

Until the mid-1980s, transport policy was considered by many as one of the least successful domains of the European integration project. However, from the early 1990s onwards, there are clear signs of a single European transport policy, along with the accompanying implementation of infrastructure projects. What is the explanation for such a change in pace? This paper aims to offer insight in these processes by looking at the mechanisms which form and transform this policy domain. To understand the state of a policy domain and its dynamics over time an institutional approach is taken. Two concepts in political science, ‘policy arrangements’ and ‘supranational governance’ are combined and used as a framework to analyse the European transport policy domain. This analysis describes the development of several elements: organisations, rules, the transnational society, power, resources, and the central transport discourse. It demonstrates that all of these elements have developed from an intergovernmental setting towards a more supranational one. This development was slow in the first decennia when European transport policy was rather passive, but it picked up speed in the 1980s and 1990s. In the pivotal year of 1985, pressure from the transnational society resulted in a rapid change of the rules, the resources and the discourse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1968, Jürgensen and Aldrup assessed the progress in developing a common European transport policy, announced in the founding Treaty of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1958. They concluded that “die gemeinsame Verkehrspolitik in der EWG sich zehn Jahre nach Gründung der Gemeinschaft immer noch im ‘status nascendi’ befindet”Footnote 1 (Jürgensen and Aldrup 1968, p. 7). More than a decade later, Erdmenger repeated the same observation by stating that “time and again the common transport policy has been the saddest chapter in the history of European integration” (Erdmenger 1983, p. 89). The European Round Table of Industrialists (ERT) complained that “the general trend towards European integration and increased worldwide cooperation has virtually by-passed transport infrastructure” (ERT 1989, p. 22). What is the explanation for this lack of integration,Footnote 2 especially when taking into consideration that the transport sector was already seen as one of the pillars of integration in 1958 (Title IV, Treaty of Rome)? And how can one understand the current revival of the European transport policy domain; which has put it centre stage and has resulted in influential white papers and billions of Euros invested in infrastructure projects?

The European transport policy domain has received much academic attention (Banister et al. 1995; Bayliss 1965; Bröcker et al. 2004; Jensen and Richardson 2004; Jürgensen and Aldrup 1968; Ravesteyn and Evers 2004; Stevens 2004). These contributions mainly focussed on the outcomes of the domain (transport policy in general or specific projects) or the connections to other policy fields (for example territorial cohesion or spatial planning). Here, we are interested in the mechanisms that (re)create the policy domain itself. The main goal of this paper is to offer more insight in the questions: why was it initially so difficult to achieve integration of transport policy and how did it shift to a faster mode of integration in the mid 1980s? The paper will separately trace the development of elements which directly influence (trans)formation of the transport policy domain. To this end, we will use theoretical concepts found in political science, combining the theory of ‘supranational governance’ (Sandholtz and Stone Sweet 1998) with the concept of ‘policy arrangements’ (Arts et al. 2000). After introducing European transport policy, these concepts will be discussed, accompanied by an analysis of the separate elements. Finally, this theoretical synthesis is further elaborated to highlight the crucial elements in the development of the European transport policy domain.

Introducing EU transport policy

Transport policy is receiving more attention at the European level in recent years, as increasingly more policy documents are drafted (CEC 1992, 1999, 2001, 2003a, b). At first sight it is strange that the process of integration in the transport policy domain was initially slow; as it has a clearly recognized importance for the entire European integration project. Jensen and Richardson contend that the process of European integration is closely linked to the goal of a single European market and the four freedoms: movement of goods, persons, services and capital (Jensen and Richardson 2004, p. 3). These freedoms depend heavily on a single and coherent transport network, which can enable seamless movement throughout the entire EU: “[When] trade is expanding and trade flows diverting, transport costs are of vital importance” (Bayliss 1965, p. 3). Banister et al. even state that “infrastructure is the key to an integrated Europe” (Banister et al. 1995, p. xiii).

Transport also has intrinsic characteristics which make it an important domain for European integration: it contributes an estimated 7–8% to the European Gross Domestic Product (GDP); it receives around 40% of the investments by member states (TINA Vienna 2002, p. 5); and it employs 4.1% of all employed Europeans (approximately 6.3 million people) (Bosch 2003, p. 7). Daily, “the transport industries and services of the European Union have to get more than 150 million people to and from work, enable at least 100 million trips made in the course of the work, carry 50 million tonnes of goods” on a total network of more than 3.5 million kilometres (Bosch 2003, pp. 7, 11).

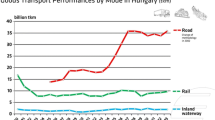

The growth of European transport is linked to the overall growth in European GDP (Barnes and Barnes 1995, pp. 79–80; Eurostat 2007) and the “socio-economic, spatial and political dynamics of society” (Nijkamp et al. 1994 as quoted in Banister et al. 1995, p. 3)—as shown in Fig. 1.

Link between transport growth and European GDP (indexed; 1985 = 100) (edited from CEC 2002)

The significance of transport and infrastructure for European integration was recognized during the founding of the EC and translated into eleven articles in the Treaty of Rome (1958), based on recommendations of the Spaak Report (1956).Footnote 3 The central themes of the transport Title were: (1) (non-) discrimination in charging, (2) development and financing of infrastructure, and (3) a common transport policy (Spaak 1956, p. 15; see also Stevens 2004, p. 37).

The development of European policy domains: a historical perspective

European Union policy domains do not fit into recognized theories of policy and political integration (Barnes and Barnes 1995). The leading two theories which explain European integration, neo-functionalism and intergovernmentalism, can be seen as two sides of a spectrum representing the power of the member states to control the integration process (Verdun 2002, pp. 10–16).

Neo-functionalism versus intergovernmentalism

Neo-functionalists (Haas 1958; Lindberg 1963; Schmitter 1970) assert that the process of integration is driven by supranational institutions, foremost by the European Commission. These supranational institutions are able to take autonomous decisions and thus influence the integration process independently from the will of the member states. Neo-functionalists assume that EU integration is driven by a spill-over mechanism (integration in one policy field triggers integration in other related policy fields).

Intergovernmentalists (Hoffmann 1964, 1966), on the other hand, claim that the member states are the dominant actors who control the integration process. All major decisions are the result of intergovernmental bargaining and its outcomes reflect the relative power of the individual member states. Although states delegate limited powers to supranational institutions, they do not relinquish sovereignty to them.

The concepts of supranational governance and policy arrangements

Wayne Sandholtz and Alec Stone Sweet (Sandholtz and Stone Sweet 1998, 1999) have developed an alternative explanation of European integration, coined ‘supranational governance’. Supranational governance describes the European Union as a series of regimes, each specializing in a specific policy domain, whereby the degree of integration varies between policy domains. Sandholtz and Stone Sweet visualise this by using a continuum with intergovernmental governance on one side and supranational governance on the other. The existence of rules/organisationsFootnote 4 along with the focus of actors on the European level jointly determine the location of a specific policy field on this continuum. Supranational governance occurs because individuals, groups and firms increasingly act across borders. Thus, the degree of supranational governance in a particular sector depends on the relative intensity of transnational activity. Those actors who gain an advantage with European level rules (and are disadvantaged by national rules) will push for more supranational governance. The result is the shift of policy making in a respective policy field from an intergovernmental to a supranational mode.Footnote 5 EU organisations produce, execute and interpret these European rules. Intergovernmental bargaining is seen as part of the process; however, instead of being the driving force behind integration, the member states primarily react to the demands of a transnational society and to supranational organisations/rules. The influence of the member states thus varies between policy fields.

From the initial step towards supranational policymaking, there are three key elements structuring this process: (1) European rules—legal constraints on behaviour which structure the interactions between political actors; (2) European organisations—governmental structures operating at the European level; and (3) transnational society—non-governmental actors who are engaged in intra-EC exchange, thereby influencing policymaking processes and outcomes (Sandholtz and Stone Sweet 1998, p. 9).

We use the three elements of supranational governance (rules, organisations and society) to analyse the development of a European transport policy. In order to better understand the evolution of transport policy, we also use the concept of ‘policy arrangements’ (defined by Arts et al. (2000)) which relates to organisation and substance. Central organisational elements are: the policy coalitions (several competing groups of people who engage in the same policy processes in order to achieve similar policy goals), power, the available resources, and the rules of the game (formal and informal rules defining the possibilities and constraints of policy coalitions). Substance relates to the policy discourse “which refers to concepts, ideas, views, buzzwords and the like, which give meaning to a policy domain” (Arts et al. 2000, p. 56). The combination of the theory of supranational governance with the concept of policy arrangements offers insight into the mechanisms which influence policy change and helps explain the change in pace of the integration of transport policy.

The development of the EU transport domain

European transport organisations

The main bodies of the European Community currently taking decisions on transport policy are the Council (Council of Ministers on Transport, Telecommunications and Energy), the Commission (to be more precise, the Directorate General for Transport until 2000, then merged into the Directorate General Transport and Energy) and the European Parliament with its Committee on Transport and Tourism. The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions have to be consulted. Several organisations providing technical and/or scientific advice in certain areas were established recently, for example the European Maritime Safety Agency in 2002 and the European Railway Agency in 2004. In addition, the common transport policy is subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.Footnote 6

In 1958, decision-making in the transport policy domain was subject to the consultation procedure; the Commission initiated proposals which the Council approved or rejected. The Council had to wait for the opinion of the Parliament, but had no obligation to incorporate this opinion into the legislative act. Thus, the Council (as the intergovernmental body of the European Community) was the dominant political institution.

In the 1980s, the Committee on Transport and Tourism of the European Parliament demonstrated its dissatisfaction with this situation through a critical assessment on the progress of the EU transport policy domain. It stated that the Commission was working too much in an incremental fashion (not guided by a clear vision) and that the Council was too passive (49 proposals were pending for a decision) (Abbati 1986, p. 74). In 1983, the European Parliament brought the Council before the European Court of Justice, which ruled partially in favour of the Parliament in 1985.Footnote 7 The Court ruled that the Council was in breach of its obligations as it failed to adopt a common transport policy (CEC 1985).Footnote 8 The political effect was significant, resulting in the drafting of the first White Paper on transport in 1992 (see below).

With the Treaty of Maastricht (1993), European transport policy moved to the co-decision procedure (Article 251 EC), meaning that the European Parliament does not only give an opinion, but it also has to agree with the proposal. If the Parliament and the Council cannot reach an agreement, a conciliation committee works on reaching a compromise. Thus, the Parliament has a right of veto, sharing equal power with the Council. Initially this procedure was only applicable to a list of important infrastructure projects, but in 1997 it was extended to include all transport legislation (Stevens 2004, p. 78). This new situation was immediately used by the Parliament; it sought to find a new political equilibrium concerning transport policy-making. In a first “rather bloody co-decision and conciliation process”, the European Parliament flexed its muscles, “as it asserted its new role in EU decision making” (Jensen and Richardson 2004, p. 130). The dispute centred the question: who was to decide on the reallocation of significant transport budgets, the Council or the Parliament?

The new power balance led to a shift of focus away from only defining guidelines towards implementing and enforcing European transport policies. This is especially visible in the case of infrastructure, which was subject to the co-decision procedure 5 years prior to other policy areas. Currently, there are six high ranking corridor coordinators who push forward the hampered development of a European transport network. In addition, there is currently a new proposal by the Commission to set up a “Trans-European Transport Network Executive Agency” (CEC 2005). This agency would provide supranational guidance to the progress of all European infrastructure projects.

Supranationalism is increasingly present in the operational frameworks of formal European transport organisations, as illustrated by the dispute between the Parliament and the Council. This is a typical policy domain dispute, where governance shifts from the intergovernmental (Council) to the supranational (European Parliament).

European transport rules

We will not go into detail on all laws and rules developed in the past 50 years, focusing instead on important transport legislation which influences the behaviour of transport stakeholders (for example, lower-tier governmental bodies and investors). These developments can be grouped in four broad historic periods in the rule making process.

The period from 1958 to 1970 started with the Title IV in the Rome Treaty, which only gave broad outlines for common rules typified as a “relative harmonization minimum [which is] far too general” (Bayliss 1965, p. 2; Jürgensen and Aldrup 1968, p. 94). The articles of Title IV can be seen as “flags (…) marking the minefield of explosive disagreement” (Stevens 2004, p. 40). Article 74 EEC (new Article 70 EC) described that a common transport policy has to be developed as a framework for future rules and policies. Article 75 EEC (new Article 71 EC) specified that these rules should focus on international transport to, from, or across member states and conditions under which non-resident carriers may operate in other member states. This article also stated that the Council has to act unanimously. By implying that all transport ministers should first agree on new rules it consequently renders the domain intergovernmental. In 1961, the Commission initiated the first draft of a common transport policy, accompanied by an action programme (CEC 1961). After some adaptations, the Parliament agreed with this plan; but the Council could not agree unanimously. Some of the principles of this unauthorised policy proposal were implemented later (for example the ability for European bodies to directly intervene in undesired national transport decisions and the abolishment of state support and discrimination of non-state carriers). Only in 1967, when transport policy became subject to qualified majority voting, some progress was made with the adoption of a general transport policy document and a small number of rules.

The period from the early 1970s up to the early 1980s can be typified as a period which started with a revival, but finished with new frustrations between the rule-making organisations. The Commission was not pleased with the achieved progress and developed a 5-year program (CEC 1971), which had minor impact as only marginal measures were adopted by the Council. In 1973, a report was published including an extended scope of transport policy, linking it to other policy domains and suggesting rules, in order to align the transport systems, planning, financing systems and the possible introduction of infrastructure charges (CEC 1973). Again, the Council took no action to approve this document (Stevens 2004, p. 49). The European Court of Justice did put additional pressure on the policy domain, by declaring that Article 48 EEC (now Article 39 EC) on the freedom of movement is also applicable to the transport domain.Footnote 9 Supported by the European Parliament, the Commission developed a list of rules and measures corresponding with the 1973 report; however the Council again failed to reach agreement on these rules.

The third period started in the mid 1980s, with a call by the Commission for a fresh start and for renewed concentration on achievable (but significant) transport rules. In accordance with the general European line, there were several calls to initiate a process of liberalisation in the transport domain (CEC 1983a, b). The transport domain once again became a vital part of the general unification project. It was judged that for a viable free movement in a unified Europe, more integration of transport rules was of crucial importance (and was indeed introduced with the Single European Act). In 1990, an action plan for infrastructure projects of European importance was introduced. Enforced by the Council’s decisions in 1993, it resulted in European road, rail and inland waterways network plans (Trans-European networks).

The Treaty of Maastricht (1993) revitalised the progress in the transport domain by restating its importance and by emphasising infrastructure development. In the same year, a first transport White Paper was published, laying down a common transport vision and policy, again with a focus on infrastructure development (CEC 1992). The Commission realized that “efforts and resources should be concentrated on a small selection of high priority projects” (Lyons 2000, p. 167). In the light of Article 155 of the Treaty of Maastricht, projects were chosen which “had economic benefit, improved safety, reduced congestion, [created a] cleaner environment and improved choice” (Lyons 2000, 163). In 1995, a developed transport action plan showed a broader coherent approach towards European transport policy (CEC 1995). In 1998, the new White Paper showed an ambitious transport policy domain, aiming for a shift of traffic from road to rail and the introduction of road charges (CEC 1998). A 2001 revision of the White Paper introduced over 60 rules and measures with the overarching goal of breaking the self-enforcing link between economic growth and the growth of (unsustainable) transport (CEC 2001). The list of infrastructure projects was also revised. It was recognised that there were considerable implementation problems. In 2005, a report from the Commission signalled that only limited progress in transnational networks has been made and that new European initiatives (steering committees, ambassadors etc.) were needed in order to generate additional impetus. The previous focus on a modal shift was dropped and now the main aim was to facilitate intermodal traffic.

During the first two periods European transport rules see limited progress. The Council did not comply with the goals and ambitions set in 1958 and only passed a small number of the numerous rules developed by the Commission and the European Parliament. The mid 1980s brought some changes and progress with a focus on infrastructure plans. Most notably after the Treaty of Maastricht, many rules were developed and enforced, including issues other than infrastructure schemes.

Transnational transport society

Here, we will discuss the European Round Table of Industrialists, described by some as “the single most powerful business group in Europe” (Gardner 1991, p. 48) and seen as one of the scant pressure groups which can actually change European policy (Endo 1999). We use the lobbying activities of the European Round Table as a proxy for cross-border transactions.

The European Round Table pressures the relevant European institutions on all topics that are relevant for the larger business community. During the 1980s it focused its attention in particular on the European transport domain. They felt that European infrastructure was not competitive with other global players, especially due to the border crossings, and started to lobby through a series of official reports. In 1984, the first report on infrastructure focused on the missing cross-border links in the infrastructure network (ERT 1984). In 1987, the following report addressed many aspects of the transport domain, from policy coordination to technology development (ERT 1987). A 1989 report addressed the inadequacy of the European transport policy domain and its decision-making processes, highlighting a growing need for a renewal of the existing infrastructure networks (ERT 1989). With the ‘Missing Networks’ report, the European Round Table addressed the outdated forms of organisation and decision-making, which produced underinvestment and created a crisis in the European transport networks (ERT 1991a). In the same year, the European Round Table provided an agenda for the future of European integration, emphasizing the role of transport (ERT 1991b). Before the European Round Table realigned its focus to other domains, their last report on transport in 1992 proposed the founding of a supranational centre for infrastructure issues (ERT 1992). Thereafter, the focus of the European Round Table shifted to other areas and to date there has been no new transport related report published.

These reports played a crucial role in framing the absence of adequate infrastructure into a critical policy problem for the European integration project (Jensen and Richardson 2004, pp. 73–75 and pp. 101–102). Figure 2 shows a powerful image, illustrating the higher transport costs (in time and money) when compared to the USA (a key market competitor of Europe). This discrepancy is used by the transnational society to create political awareness for the importance of a single European transport network. A great majority of the cross-border links recently developed in the EU were proposed in one of the European Round Table reports: namely the Øresund link, Trans-Alp connections and the Channel tunnel between France and England.

The cost of a non-united European transport network; truck transport times compared between the USA and Europe (ERT 1991b, p. 38)

Using the European Round Table as a proxy for the transnational transport society, it is striking to note that the bulk of their lobbying efforts took place in a relatively short time span (1984–1992). Before and after this period, the European Round Table did not publish any report on this matter as, according to their spokesperson, the members felt to have conveyed their message clearly and witnessed some of the expected results of their activities.

European transport power and resources

The amount of European funding assigned to the transport domain (especially for infrastructure projects) is one of the clearest indicators of the actors’ ability to mobilise transport resources.Footnote 10 Consequently, we analysed the funds which are directly or indirectly allocated for developing infrastructure.

Until the 1980s, the general level of investment in transport infrastructure in the EU had been stable at about 1% of the Gross Domestic Product (CEC 1992, para. 143). “Despite a steady increase in traffic flows in the EU, investment in inland transport declined from 1.5 to around 1% between 1975 and 1980” (Barnes and Barnes 1995, p. 81). However, from 1980 onwards, the European budget shows a steady increase of funds earmarked for transport. It should be noted that this budget is used for co-financing infrastructure projects up to a maximum of 30%. The other 70% is contributed by the member states and other stakeholders. In 1993, a sharp jump in funding can be seen with the introduction of the Cohesion Fund, primarily earmarked for funding infrastructure projects (see Fig. 3).

There is an additional dimension to this increase in European funding, when it is compared with the combined annual infrastructure expenditures of all member states. Figure 4 shows a steady increase until 1993, when the figure stabilized around 70 billion Euros (CEC 2000, p. 10).

Total annual expenditure of European member states related to transport infrastructure (CEC 2000)

The Commission is now looking for new ways to increase the funds earmarked for infrastructure. In a 2005 memorandum, Transport Commissioner Barrot wrote that the budgets (although significant) are still insufficient to implement the 30 priority projects. He proposed to increase the budget (for these 30 Trans European Network-projects alone) to 140 billion Euros for the period 2007–2013. This amount should be collected by increased returns from infrastructure charges and national funding (CEC 2005), along with an increase in EU contribution from 30% to 50%. Also, the participation of the private sector in the funding of these projects is discussed; however, as emphasized by a representative of the largest lobby group of potential investors in such infrastructure projects (ASECAP), private companies are only willing to invest if there is a clear and long-term European vision underlying the proposed networks and individual projects. Otherwise the risks would be too great.Footnote 11

European transport discourse

We use the term discourse as a shared view by a group of actors on (1) how something is, (2) how something should be and (3) how to get from the existing situation to the desirable state of affairs (see also Arts et al. 2000, p. 66). In the beginning of European integration, (with six member states) there were two groups with sharply conflicting discourses on transport. Both were based on economic market principles and saw the existing situation as suboptimal, but both had conflicting ideal visions on how to overcome the current problem (Jürgensen and Aldrup 1968, p. 84). One group supported the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ approach that transport should be completely market led, with low responsibility of public authorities and free choice of transport for carriers and clients (‘laissez-faire’). A second group strongly supported the opposing ‘Continental approach’, which interprets transport as an instrument of public policy, where public intervention with the aim of correcting market failure is seen as inevitable or at least preferable (Abbati 1986, p. 52). The biggest promoters of this discourse were West-Germany and France (Stevens 2004, p. 23). Both discourses were deeply rooted in culture, history and social models of the member states (Hayward 2001, p. 265).

Over time, a new discourse developed in other policy domains which addressed non-economic foundations for European integration. The free movement of goods, persons, services and capital should create a stronger Europe, one which is able to compete with the USA and the Soviet Union (later Russia), also in geopolitical issues. However, the focus on economic integration in the transport domain persisted until 1985, as did the deadlock in the Council. As a result other (non-economic) transport matters were also hampered in their development (e.g. a common transport vision, or a single European network).

Two crucial events took place in 1985. Firstly, the already discussed judgment of the European Court of Justice in (European Parliament vs. the Council) forced the Council to make progress on important issues. Secondly, Jacques Delors was appointed president of the Commission and remained on the post for a decade. Many authors see this decade as the real start of European integration (see Bache and George 2006; Barnes and Barnes 1995; Dinan 1998; Hix 2005; Peterson and Bomberg 1999). Delors focused on the following key points: (1) too many rules and too few results; (2) the internal market needed to be completed and (3) addressing these points required a strong focus on implementation and policy reforms. This strongly supported the European Court of Justice’s ruling on the transport domain.

Delors proved to be a champion for the transport policy domain, because he saw infrastructure projects as direct and indirect job creating mechanisms and as a crucial part of advancing the internal market. It could create employment in peripheral areas and link them to central regions of Europe. This view united the member states in efforts to create a list of the most beneficial projects: the Trans European Network lists. The first list (the Essen list developed by the High Level Group chaired by Christophersen) was selected from a long catalogue of national wish-list projects, which were mainly targeted at increasing employment. The total number of jobs created by these projects were projected between 100,000 and 200,000, with up to 400,000 additional jobs projected as indirect growth (Christophersen 1995, p. 39).

With the fall of the Iron Curtain (1989) and the collapse of the USSR (1991), a new transport situation emerged, which imposed large East-West transport demands on a strongly North-South oriented network. Infrastructure was seen as the main instrument for re-uniting these two parts of Europe. But the potential for success of the common transport discourse (focused on infrastructure projects) was hampered by a lack of finance and therefore, two new competing discourses emerged. One came from the environmental domain, which first criticized the lack of environmental attention in the transport domain, but then proposed different selection criteria for projects instead (focusing on a modal shift from road to rail and a more sustainable transport policy). The other discourse wanted to place transport more at the heart of European integration and emphasized the role of infrastructure networks in the core objectives of the European Union: cohesion, equal opportunities for all citizens, bridge-building to new and future member states and structural improvements of peripheral areas (CEC 2002). To achieve the goals of the latter discourse, the transport budget should be increased (for example through the Cohesion and Structural Funds). Although the two discourses are aiming at different ideals, they are not as conflicting as the previous two. The new dichotomy creates longer decision-making processes and sometimes conflict,Footnote 12 but it does not create deadlocks, nonetheless due to the fact that the participants in both discourses are no longer only ministers of member states. Lobby groups, committees and stakeholders (all with significant interest to keep the issue moving forward) have also joined the discourses.Footnote 13

Until the 1980s the European transport domain suffered from two conflicting economic discourses that were deeply rooted in the world views of member states. This created a deadlock in the Council, making unanimous decision-making impossible. Delors shifted the focus away from pure economic reasoning towards a vision of infrastructure as a job creating mechanism and as a crucial element of the internal market. Together with the 1985 ruling of the European Court of Justice, this new focus aligned the member states and their interests. Changes in the context and the developing transport problems were also strong incentives, stimulating the synthesis of a single central discourse. Recently, new conflicts have risen between the socio-economical perspective and the environmental protection perspective on infrastructure. Yet, this dichotomy is not as paralysing as the initial conflict.

Conclusion: European transport synthesis

The analysis of the five elements of the transport policy domain, based on supranational governance theory and policy arrangements, shows that all have more or less evolved from the intergovernmental more towards the supranational end: (1) more decision-making power for the European Parliament and Commission; (2) stronger European rules; (3) a shift of the stakeholders’ attention away from the nation states towards Brussels; (4) growing European funding replacing national funding; and (5) a stronger discourse emphasizing the role of European transport policy. Additionally, there are strong interrelations between these elements.

The pivotal year is 1985; thereafter, increasingly stronger rules governing transport policy were established on a European level, tremendously strengthening the supranational element of transport policy. The European Court of Justice contributed to this boost by creating a new balance between the Commission, the Parliament and the Council. It is also around this year that the transnational society (represented in this paper by the European Round Table) applied significant pressure on the European institutions. The appointment of Delors as President of the European Commission generated an extra impetus for the transport policy domain. When his term ended in 1995, a common transport policy document was published and many Trans-European-Network-projects were in place. With such instruments in place, the transnational transport society got a new push; regions, non-governmental organizations and other lobby groups (even environmental protection groups) turned their attention to influencing the lists of infrastructure projects, especially through the empowered Parliament (Jensen and Richardson 2004, p. 35).

The discourse conflict can be seen as the main element which was curbing integration well before 1985. The lack of consensus on the general aims of European transport policy resulted in the vague transport rules found in Title IV of the Rome Treaty. Another effect of this conflict is the institutional deadlock in the Council, preventing it from achieving consensus on rules and policy directions due to strongly opposing blocks of ministers. With the development of a common discourse under Delors, fuelled by outside pressures (notably the European Round Table), the deadlock in the Council was broken and progress was first made on infrastructure projects (the importance of which was recognised by all actors) and then on a common transport policy. In the early 1990s, when the absence of strategic funds for financing this ambitious infrastructure program was painfully clear, the focus shifted to creating more financial opportunities. The establishment of the Cohesion Fund was a big step forward and it attracted additional attention from the growing transnational transport community.

Currently, the transport policy domain has a central place in the European integration project, supported by important white papers and legislation. Also, more tangible accomplishments in the form of infrastructure projects are now realized, partly due to European funds (for example the Betuwelijn, the tunnel between France and England and the Øresund bridge). Other infrastructure projects that were seen as missing links in an European network are underway (for example the new Gotthard rail tunnel and Pyrenean rail links). One result of the growing ambitions in the transport area is a loud call to earmark more funds for infrastructure. Implementation difficulties have resulted in initiatives which called for an increased role of EU institutions and regulations in transport matters (especially cross-border projects). New rules are proposed by the Commission to allow a larger share of European investment in projects than the currently allowed maximum of 30% (CEC 2005).

Although this analysis illuminates the direction and pace of development in the European transport domain, its future path is difficult to project. We do not expect it to continue growing at the accelerated pace of the past two decennia. Currently, other policy domains (notably environment) are increasingly hampering progress in the transport domain. Contextual developments (concerns on increased supranational tendencies mirrored in the difficulties surrounding the new Constitutional Treaty) also hamper additional advancement. Our analysis suggests that progress is extremely difficult when a policy domain reaches the point of full supranationality, due to multiple sources of resistance, such as: the member states which are losing power; the citizens who see unwanted developments and crucially the other conflicting (and more mature) policy domains. However, according to the theory of supranational governance, recourse to strengthening intergovernmental governance seems highly unlikely (Sandholtz and Stone Sweet 1998, p. 16).

Notes

“Ten years after the founding of the Community the common transport policy of the EEC is still in a ‘status nascendi’” (translation by the authors).

In this paper we focus on political integration which can best be described in the words of Leon Lindberg (1963) as “[…] (1) the process whereby nations forego the desire and ability to conduct foreign and key domestic policies independently of each other, seeking instead to make joint decisions or to delegate the decision-making process to new central organs; and (2) the process whereby political actors in several distinct national settings are persuaded to shift their expectations and political activities to a new center.” Physical integration of transport networks can be a result of political integration.

As it is rumoured, the transport delegates present at the negotiations were locked in a room and the negotiators, frustrated by failure to agree on a common transport policy, were only willing to led them out if they presented an agreed-upon transport policy framework Bayliss (1965).

Sandholtz and Stone Sweet use the term organisation in a sociological sense. The sociological literature on organisations and institutions would label the European Parliament, the European Commission, and the Council of Ministers as organisations, while the rules governing their interaction and the rules they produce would be called institutions. For an introduction to the study of institutions and organisations see Scott (2007).

Note that in this model the dominant direction of the course a policy field takes is from intergovernmental to supranational governance. Although one can easily imagine that policy-making in certain fields is changed from a supranational back to an intergovernmental mode of governance, historical examples of policy fields taking that direction are hard to find.

For a more thorough description on how these organizations deal with transport, see Te Brömmelstroet (2005).

13/83 European Parliament vs. Council of the European Communities [1985] ECR 1513.

For a discussion of the mechanisms that turn judgments into political decisions see Nowak (2007).

167/73 Commission of the European Communities vs. French Republic [1974] ECR 359.

We are aware that there are more indicators for this policy domain aspect, that there are more sources of funds and that the focusing only on infrastructure projects is limiting; however, taking into account the scope of this research and the available data, this serves as a good proxy.

The interview was held in June 2005 with mister Dionelis, general secretary of ASECAP—the European Professional Association of Operators of Toll Road Infrastructures.

At the moment of writing, Poland is resisting the development of a highway, claiming that it destroys valuable nature areas (see:http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2007/aug/02/endangeredhabitats.endangeredspecies?gusrc = rss&feed = environment).

References

Abbati, C. d. (1986). Transport and European integration. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Arts, B., Van Tatenhove, J., & Leroy, P. (2000). Policy arrangements. In J. Van Tatenhove, B. Arts, & P. Leroy (Eds.), Political modernisation and the environment: The renewal of environmental policy arrangements. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bache, I., & George, S. (2006). Politics in the European Union. New York: Oxford University Press.

Banister, D., Capello, R., & Nijkamp, P. (1995). European transport and communications networks. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Limited.

Barnes, I., & Barnes, P. M. (1995). The enlarged European Union. Essex: Addison-Wesley Longman Limited.

Bayliss, B. T. (1965). European transport. London: Kenneth Mason Publications Limited.

Bosch, J. (2003). Panorama of transport: Statistical overview of transport in the European Union (1970–2001). Luxembourg: EuroStat.

Bröcker, J., Capello, R., Lundqvist, L., Meyer, R., Rouwendal, J., Schneekloth, N., Spairani, A., Spangenberg, M., Spiekermann, K., van Vuuren, D., Vickerman, R., & Wegener, M. (2004). ESPON 2.1.1.;Territorial Impact of EU Transport and TEN policies. ESPON, Only available online: http://www.espon.lu.

CEC. (1961). Memorandum on the general lines of a common transport policy. Brussels: The Schaus Memorandum.

CEC. (1971). Fifth general report on the activities of the European Communities in 1970. Brussels/Luxembourg: Office for official publications of the European Communities.

CEC. (1973). Development of the common transport policy. Brussels.

CEC. (1983a). Memorandum by the Netherlands government on a common transport policy. Brussels.

CEC. (1983b). Progress towards a common transport policy: Inland transport. Brussels.

CEC. (1985). Completing the internal market. Brussels.

CEC. (1992). The future development of the common transport policy, COM (92)494. Brussels: CEC.

CEC. (1995). The common transport policy action programme 1995–2000. Brussels.

CEC. (1998). White paper on fair payment for infrastructure use. Brussels.

CEC. (1999). Moving forward: The achievements of the European common transport policy. Brussels: EC publications office.

CEC. (2000). EU transport in figures; 2000. Luxembourg: Office for official publications of the European Communities.

CEC. (2001). White paper; European transport policy for 2010: Time to decide. Luxembourg: Office for official publications of the European Communities.

CEC. (2002). Trans-European transport network; TEN-T priority projects. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEC. (2003a). Europe at a crossroads: the need for sustainable transport. Brussels: DG for Press and Communication.

CEC. (2003b). Revision of the Trans-European transport networks “TEN-T”. Brussels: CEC.

CEC. (2005). Memorandum to the Commission from President Barroso in agreement with Mr. Barrot: Implementing the Trans-European networks. Brussels: Commission.

Christophersen, H. (1995). Trans-European networks. Luxembourg: EC publications office.

Dinan, D. (1998). Encyclopaedia of the European Union. London: Macmillan.

Endo, K. (1999). The presidency of the European Commission under Jacques Delors: The politics of shared leadership. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Erdmenger, J. (1983). The European Community transport policy. Aldershot: Gower.

ERT. (1984). Missing links. Brussels: ERT.

ERT. (1987). Keeping Europe Mobile; a report on advanced transport systems. Brussels: ERT.

ERT. (1989). Need for renewing transport infrastructure in Europe. Brussels: ERT.

ERT. (1991a). Missing networks: A European challenge. Brussels: ERT.

ERT. (1991b). Reshaping Europe. Brussels: ERT.

ERT. (1992). Growing together: One infrastructure for Europe. Brussels: ERT.

Eurostat. (2007). Panorama of transport: edition 2007. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Gardner, J. N. (1991). Effective lobbying in the European Community. Deventer: Kluwer.

Haas, E. B. (1958). The uniting of Europe: Political, social and economic forces 1950–57. London: Library of World affairs.

Hayward, J. (2001). In search of an evanescent European identity. In A. Guyomarch, H. Machin, P. A. Hall, & J. Hayward (Eds.), Developments in French politics 2. Basingstoke: Paalgrave, Houndmills.

Hix, S. (2005). The political system of the European Union. Hampshire, New York: Palgrave.

Hoffmann, S. (1964). The European process at Atlantic cross purposes. Journal of common market studies, 3, 85–101.

Hoffmann, S. (1966). Obstinate or obsolete? The fate of the nation state and the case of Western Europe. Daedalus, 95, 862–915.

Jensen, O. B., & Richardson, T. (2004). Making European space: Mobility, power and territorial identity. London: Routledge.

Jürgensen, H., & Aldrup, D. (1968). Verkehrspolitik im europäischen Integrationsraum. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

Lindberg, L. (1963). The political Dynamics of European integration. London: Oxford University Press.

Lyons, P. K. (2000). Transport policies of the European Union. London: EC Inform

Monbiot, G. (2001). Stealing Europe: The great European dream has been subverted by corporate power. http://www.zmag.org, visited on 11th of August 2005.

Nowak, T. (2007). How judgments become law and how law restricts judgments. The influence of the European Court of Justice on the legislative process of the European Community. Groningen: GrafiMedia.

Peterson, J., & Bomberg, E. (1999). Decision-making in the European Union. London: Macmillan press.

Ravesteyn, N., & Evers, N. (2004). Unseen Europe: A survey of EU politics and its impact on spatial development in the Netherlands. Rotterdam: Ruimtelijk Planbureau.

Sandholtz, W., & Stone Sweet, A. (1998). European integration and supranational governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sandholtz, W., & Stone Sweet, A. (1999). European integration and supranational governance revisited: Rejoinder to Branch and Øhrgaard. Journal of European Public Policy, 6(1), 144–154.

Schmitter, P. (1970). A revised theory of regional integration. International organization, 24, 836–868.

Scott, W. R. (2007). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Spaak, H. (1956). The Brussels report on the general common market. Luxembourg: Information service high authority of the European community for coal and steel.

Stevens, H. (2004). Transport policy in the European Union. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Te Brömmelstroet, M. C. G. (2005). European transport Inc.: The history, present and future of the European transport policy domain. Msc. thesis. University of Groningen, Groningen

TINA Vienna. (2002). Status of the Pan-European transport corridors and transport areas. Vienna: European Commision D.G. Energy and Transport.

Verdun, A. (2002). Merging neofunctionalism and intergovernmentalism: Lessons from EMU. In A. Verdun (Ed.), The Euro: European integration theory and economic and monetary union (pp. 9–28). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dominic Stead, Jochem de Vries, Nikola Stalevski, two anonymous referees and the special issue editors for their comments on previous versions of this paper; and Railforum for financially supporting the research.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

te Brömmelstroet, M., Nowak, T. How a court, a commissioner and a lobby group brought European transport policy to life in 1985. GeoJournal 72, 33–44 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9163-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9163-7