Abstract

While most people in post-industrial societies, such as The Netherlands, continue to live as nuclear families, new household arrangements have emerged in which couples no longer commit to living in one shared residence. One such household arrangement is the commuter partnership, in which one partner lives near work part of the time. The objective in this article was to gain a better understanding of the sustainability of commuter partnerships and to contribute to uncovering the function that this household arrangement can have in the coordination of parallel careers of different household members over time. The study draws on in-depth interviews with both individual partners in 30 commuter partnerships with at least one residence located in The Netherlands, and a follow-up survey of the same commuter couples several years later. Our findings indicate that, for most couples, the commuter partnership should not be regarded as a prelude to family migration, but rather as a household arrangement by which family migration is avoided altogether, either for a limited period, or as a long-term alternative to the nuclear family. The findings further indicate that, when couples look on their commuter partnership as the result of their individual choice, they generally envision the future duration of their commuter partnership quite accurately. When their choice is guided by the external circumstances of job contracts, couples appear to be less accurate in predicting the future duration of their commuter partnerships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, sociologists and (population) geographers have pointed out that the continuity of individuals’ life courses has become pressured in late modernity (for example: Boyle et al. 1998; Elder 1994; Giddens 1991). Over the life course, adaptability is required of individuals and households regarding choices in the basic life domains of work, partnership, family, and residence (Moen and Wethington 1992). This pressure can be ascribed in part to the societal changes occurring in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, such as the expansion of education and its importance for individual development, fluctuations in the economic climate, the growth in female labour participation, the delay of family formation, and the increase in divorce and partnership dissolution (Liefbroer and Dykstra 2000; Van de Kaa 1994). Individualization and the associated ideology that individuals are personally responsible for their life-course choices and life plans are further developments that have impacted on individual lives in late modernity (Beck 1992; Giddens 1991).

These societal developments have led to an increased variety in the geographical organization of household arrangements in post-industrial societies, albeit that most families continue to live as nuclear families who share one residence and commence their complex daily activity patterns from this location (Bailey et al. 2004; Fagnani 1993; Hardill et al. 1997; Hochschild 1997; Karsten 2003).

Relatively recently, however, household arrangements have emerged in which couples no longer commit to living in one shared residence, enabling them to adapt to circumstances and combine individual and common commitments. Examples of such household arrangements are Living-Apart-Together and commuter partnerships (Haskey 2005). In the commuter partnership, which is the object of study here, the nuclear-household arrangement is replaced by one in which one partner lives near his or her work for part of the time and away from the communal family residence, because the commuting distance is too great to travel on a daily basis. Few previously published studies of this type of partnership in the USA and the UK indicate that some couples regard a commuter partnership as an unsustainable, temporary alternative to the nuclear family, while other couples regard this household arrangement as a lifestyle that they expect to be sustainable for many years (Gerstel and Gross 1984; Green et al. 1999a, b). A study among commuter partnerships in The Netherlands showed that this household arrangement can be regarded as an alternative to family migration or not migrating (Van der Klis and Mulder 2008).

Despite these different time horizons of couples in commuter partnerships, it has as yet not been explored how commuter partnerships actually develop over time. Previous studies into commuter partnerships have not provided a longitudinal view that would allow the comparison of respondents’ stated intentions regarding the future of their commuter partnership and their actual experiences several years later. Nevertheless, because the commuter partnership might become an increasingly common alternative geographical household arrangement to the nuclear household in today’s flexible society, understanding the extent to which commuter partnerships are temporary or longer term household arrangements in couples’ life courses is relevant. The time horizons that couples have in mind are influenced by the circumstances they perceive to be important; these can be of either an individual or an external nature (Hitlin and Elder 2007). However, perceived time horizons may not coincide with the actual durations of certain life-course phases. A commuter partnership chosen as a temporary solution might last much longer than the couple initially intended; on the other hand, a commuter partnership embarked on as a lifestyle choice could last for a shorter period than anticipated.

The objective in this article is to gain a better understanding of the sustainability of commuter partnerships and to contribute to uncovering the function that this household arrangement can have in the coordination of parallel careers of different household members over time. The article studies commuter partnerships that are based in The Netherlands and who have either two residential locations in The Netherlands, or one location in The Netherlands and a second location in another country. The questions addressed are: What time horizons do couples have in mind for the future course of their commuter partnership, and to what extent do these time horizons coincide with the actual course? How can continuity or change in couples’ life courses explain the development of their household arrangement over time?

After looking further into the academic concepts used, we elaborate on the context of The Netherlands and on the characteristics of the selected respondents. We then discuss the experiences reported by commuter couples over time, using longitudinal data that consist of individual in-depth interviews with both partners in 30 commuter couples who are based in The Netherlands, and a follow-up survey of the same 30 couples carried out 2–4 years later.

Theory and previous research

The commuter partnership can be regarded as a household arrangement that some couples choose as an alternative solution when they are considering whether to migrate or not (Van der Klis and Mulder 2008). The choice for a commuter partnership can be motivated by a couple’s wish to match the individual career commitments of both partners, particularly in the case of dual-earner households. Family migration is shown to occur most often for the benefit of occupational and educational careers (Mulder 1993). However, when dual-earner households migrate, one spouse usually has to give up a job at the location of origin to enable the other spouse to start a job at the destination location. A spouse who joins in migration for the benefit of the partner’s career is referred to in the migration literature as a trailing spouse or tied mover. Similarly, a tied stayer is a spouse who declines the option of family migration for the benefit of his or her own occupational career, because this would harm the partner’s career (Cooke 2003; Mincer 1978). Trailing spouses have a smaller probability of obtaining (suitable) employment after family migration and they tend to have lower incomes (Bielby and Bielby 1992; Boyle et al. 2001; Clark and Huang 2006; Cooke and Bailey 1996; Cooke 2003; Jacobsen and Levin 1997; Shihadeh 1991; Smits 1999; Van Ommeren 2000).

In some couples, partners are not willing to make such a sacrifice for the benefit of their partner’s occupational career and instead opt for a commuter partnership. Other reasons that can influence the choice for a commuter partnership can be found in the life domains of family and residence. Sometimes, family migration is rejected as an option when one partner finds a job at a longer distance from the shared home and the other partner has a specific social attachment to the original region, city or residence. The social and residential stability of children can also provide a rationale for choosing not to migrate and to opt for a commuter partnership instead when one partner finds a job at a greater distance from the family home. A commuter partnership can thus provide a solution when a couple rejects both family migration and not migrating, either temporarily or for the longer term (Van der Klis and Mulder 2008).

As a household arrangement, the commuter partnership can be looked on as an alternative to a nuclear-family arrangement. The nuclear family is characterized in numerous definitions as a social group who live together in a shared residence (for instance: Berelson and Steiner 1964; Degler 1980; Murdock 1965). In their study of dual-career commuter marriages in the United States, Gerstel and Gross (1984) point out that this view of the nuclear family is grounded in empirical descriptions of the typical, modern, Western family. Gerstel and Gross criticize this definition of the family as a one-sided view that does not represent the lives of many Western families. Interestingly enough, their own empirical findings showed that the commuter marriage was regarded by most of their respondents as a temporary situation, even when these couples were quite unsure when it would end, because most of them regarded living together as an integral part of being married. Green et al. (1999a, b) studied dual-location households in the United Kingdom in which one spouse travelled weekly on long-distance trains between central London and its wider region. Their study showed that, besides those couples who felt they were pushed into a commuter partnership and regarded it as a temporary phase, there were also families for whom the dual-location household could be interpreted as a lifestyle. These lifestyle commuter families opted for a dual-location household, because that enabled them to combine well-paid and high-status employment in central London with affordable and child-friendly residential settings at a greater distance from the city. These families knew from the start that this specific combination of occupational and residential commitments automatically implied a long-term dual-location household and they expected it to be sustainable for the medium term. What the studies by Gerstel and Gross (1984) and Green et al. (1999a, b) show is that the commuter partnership can be an anticipatory choice based on the anticipation of an expected or desirable future life-course event that will terminate the commuter partnership and result in all family members reuniting in one residential location, or that it can be a choice made for the longer term.

In his work on late modern society, Giddens (1991) points out that strategic life planning has become of special importance for individuals as a planning and timing device for significant events in the life course. Because the individuals in partnerships form networks of interdependent or linked lives, there is a need to synchronize both spouses’ individual preferences and common interests (Bailey et al. 2004; Heinz and Kruger 2001; Jarvis 1999). Depending on their circumstances and the importance attached to specific individual or common life plans, the time horizons that couples have in mind for the duration of their commuter partnership can differ. These horizons can be focused on either short-term or long-term goals, and they can vary between well-defined periods of time or open-ended time frames (Hitlin and Elder 2007). It is likely that couples will apply different time horizons depending on certain phases in the life course, such as the years before they choose to have children, in the life phase when there are dependent children in the household or when a couple is in the life-course phase of empty nester. The resources available to the household and restrictions hampering them also influence the household’s choice options over time (Mulder and Hooimeijer 1999). For example, a household might opt for a commuter partnership more easily if the rise in income compensates for having to pay for two residences. Also, having children might form a restriction for some to migrate and lead to opting for a commuter partnership instead. For others, instead, having children might rule out a commuter partnership. Furthermore, being in a dual-income household can be a restriction for family migration because, as pointed out before, this may lead to a tied move for one partner. On the other hand, not migrating may lead to a tied stay for the other partner.

When we look at the actual course of a commuter partnership over time, it is important to recognize that life courses are not solely directed by personal preferences and couples’ self-initiated choices. Opportunities and constraints that are created outside the individual or couple determine their set of choice options (Mulder 1993). Unforeseen circumstances and chance are relevant for the development of the life course over time. Such circumstances can be personal in nature, for instance in the case of sudden illness, or they can be related to societal conditions, for instance when the changing conditions in regional labour markets and the global and local economy result in the loss of one’s job or in a growing share of temporary job contracts at the cost of tenured positions. The increased emphasis on a flexible economy requires households to be flexible and adaptive regarding work and consequently also regarding the choice for residential location and household arrangements. In that sense, the life course is contingent in character and its predictability is limited for individuals and families (Brannen and Nilsen 2005; Sennett 1998). This contingent character is probably also relevant for the continuity of commuter partnerships.

Commuter partnerships in The Netherlands

In order to understand the function of a commuter partnership in the life courses of the couples studied, it is relevant to have some knowledge of the particular context that these couples are part of. The couples studied all have a shared residence in The Netherlands. The greatest concentration of employment opportunities is to be found in the Randstad region, with the larger cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague (Dieleman and Musterd 1992). Related to the high population density, this part of The Netherlands is struggling with mobility problems like traffic jams and train delays. This reduces the accessibility of work places and increases strategic residential location choice; especially among dual earner households (Karsten 2003; Van Ham et al. 2001). Living in the north or the south of The Netherlands while working in the Randstad leads to travel times that are well above a reasonable daily commute.

The economy of The Netherlands is characterized by a large service sector with a strong international orientation. This orientation is strengthened by international treaties such as the European Schengen Treaty, and also by the ample opportunities for international travel through high speed railways and the hub position of Schiphol Airport near Amsterdam. This economic position leads to both the attraction and sending out of highly-skilled expatriate workers (Musterd et al. 2006).

The Netherlands is nowadays one of the European countries with the highest participation of women on the labour market, although a majority of women work part-time (Portegijs and Keuzenkamp 2008; SCP and CBS 2006).

So far, it has been difficult to estimate how many commuter partnerships exist in The Netherlands, since no official figures are available. It is estimated that, of the couples with and without children in The Netherlands around 2003, less than one percent lived in a commuter partnership (Van der Klis and Mulder 2008). However, the combination of individuals working outside The Netherlands as expatriates and the growth in female labour-market participation have set the conditions for this number to grow in the future.

Selection and characteristics of respondents

The study of the development of commuter partnerships over time and the relationship between stated intentions and actual experiences several years later requires longitudinal data (Green et al. 1999a, b; Jarvis 1999). Furthermore, since the study concerns not only the variety in couples’ choices about continuing (with or without adjustments) or ending a commuter partnership but also their considerations for these choices, we opted for the use of qualitative biographical data (Bailey et al. 2004; Halfacree and Boyle 1993).

Owing to the absence of databases through which commuter partnerships could be located and selected, we searched for respondents through networking, advertising, approaching companies, and the snowball method. We used purposive sampling (also known as theoretical sampling) for the selection of respondents (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Mason 1996). A benefit of purposive sampling in explorative research is that it helps to study a specific part of the population and to select respondents on the basis of specific similarities and differences. Limitations are that it creates artificial boundaries between categories of people who are supposed to be similar in life-style, and that some forms of self-selection might take place among the respondents. Whether a couple would fit within the framework of our study was established through a questionnaire that was used in telephone or e-mail conversations. Based on the answers given in this questionnaire, couples were selected to take part in individual interviews with each spouse. We sought a variety in the types of occupation, couples with and without dependent children in the household, variation in couples’ life-course phases, and couples with two residential locations in The Netherlands as well as couples who travel between one location in The Netherlands and another in a different country, we limited the selection to people with moderate and higher skill levels. Furthermore, couples had to meet several criteria in order to fit the profile of a commuter partnership: the travel time between both locations should be well above a commuting tolerance for daily commuting; for the purpose of comparability of the respondents’ stories we ruled out Living-Apart-Together couples, who prefer separate residences in any event and we also excluded couples for whom the time spent away from the communal residence was inherent in the type of profession, such as oilrig workers, truck drivers, travelling sales representatives, and naval officers.

Thirty couples took part in the research project (see Table 1 for respondent characteristics). Fifteen couples commuted between two residences within The Netherlands, 15 others travelled between a home in The Netherlands and a location in another country; mostly West European countries surrounding The Netherlands such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and Belgium (Brussels), but also Switzerland and one non-European country (Bolivia). Fifteen couples had dependent children (of various ages) who lived permanently in one communal residence with either the mother or the father, while the other parent commuted to a location near the workplace.

Each partner of all 30 couples took part in an in-depth semi-structured interview. The partners were interviewed separately to enable each respondent to reflect on their experiences and choices from an individual point of view (Valentine 1999). The duration of the interviews was between 60 and 90 min. All interviews were carried out by the same interviewer in order to enhance the comparability of the interview material. All interviews were tape-recorded, with the respondents’ consent, and fully transcribed for the purpose of the analysis. At the end of each interview, the respondent was asked for permission to be contacted again after several years for participation in a follow-up survey (no specific moment for the follow-up was indicated at the time of the interview). All the respondents gave this permission. The couples were interviewed between 2003 and 2005; on each occasion, no more than 2 weeks elapsed between the interviews with each partner of a couple. Four couples were interviewed in 2003, eighteen couples were interviewed in 2004, eight couples in 2005. The couples were contacted for the follow-up survey in 2007. All 30 couples participated in this survey. The survey contained questions about the continuity or change in the couple’s residential, work and family circumstances, and provided plenty of opportunity for the respondents to add comments. Two-thirds of the respondents completed the survey in written form, sometimes followed by an email conversation with the interviewer in which the respondents provided additional information. One-third of the respondents completed the survey verbally during a telephone conversation with the interviewer, which in several instances led to a spontaneous open interview.

Empirical findings

The (dis)continuation of commuter partnerships

During the initial interviews, we asked respondents to reflect on their future plans or expectations for their commuter partnership. At that time, just a handful of respondents expected their commuter partnership to terminate within a year; all the others employed time horizons of at least several years.

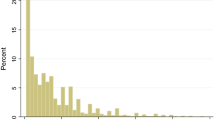

The findings from the follow-up survey about the (dis)continuation of the commuter partnerships correspond with four types of possible patterns, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Fifteen couples were living in one shared home again (patterns A and B); fourteen couples had as yet continued the commuter partnership (pattern C); and one couple had separated (pattern D).

The sustainability of commuter partnerships: possible developments over time. (adapted from Green et al. 1999b). (A) Commuter partnership for a finite period, then reunification at original family home; (B) commuter partnership as a prelude to family migration to a new location; (C) commuter partnership for an indefinite period; (D) commuter partnership as a prelude to divorce

When we take a closer look at the 15 couples who reunited in one shared home, we note that 11 of them reunited in their original family home (pattern A). Their commuter partnerships lasted for an average of 4.5 years, with the incidental exception of one couple whose commuter partnership had lasted for 12 years. For these couples the commuter partnership arrangement lasted for a middle-long term and through this arrangement they managed to avoid family migration altogether. For four other couples, the commuter partnership turned out to be a transitory phase before family migration to the new location (pattern B); these commuter partnerships also lasted for the middle-long term, with an average of 4 years. Then there were 14 couples who were at the moment of the follow-up as yet continuing their commuter partnership (pattern C), the average duration was 6 years at the time of the follow-up survey. In this group, only one couple clearly indicated that they expected to migrate to their current second location at some point in time (pattern B); four other couples indicated that they expected to reunite in their original family home in the future (pattern A); and the remaining nine couples gave no clear indication about where or when they would join up in one residence. This finding indicates that in addition to a substantial number of commuter couples who were already reunited in their original family home, or expected to do so in time (15 couples in total), there is also a notable group of nine respondents who continue their commuter partnership as a household arrangement that does not require to be changed into a nuclear household arrangement. For a much smaller number of commuter partnerships in our study it turned out to be a prelude to family migration (only five couples had migrated or intended to do so at the time of the follow-up).

The divorced couple (pattern D) had come to this decision after continuing their commuter partnership for 15 years. The method used here does not control for elements of self-selection that would be unfavourable to couples with unstable relationships. However, a study by Gerstel and Gross (1984) came to similar findings about the low incidence of divorce among commuter marriages in the USA.

In the following sections, we discuss the respondents’ explanations for the continuity or termination of the commuter partnerships. A distinction could be drawn between couples who originally envisioned unlimited time horizons and those who had limited time horizons in mind for the duration of their commuter partnership. These time horizons serve as a starting point for this discussion; the actual situations at the time of the follow-up are then set out.

Couples with an unlimited time horizon

The respondents who stated in the interviews that they expected their commuter partnership to last for an unlimited period, probably for years to come, often mentioned that they were confident that their partnership could withstand the possible pressures they might encounter. Should the situation lead to unanticipated problems or dissatisfaction, they expected to decide there and then how to cope with those circumstances. These couples could be divided into two groups: those who regarded their commuter partnership as a household arrangement that was compatible with their lifestyle choices; and the couples whose commitment to the occupational career was the engine behind their commuter partnership.

Commuting life style

In the first group of couples (seven) with unlimited time horizons in mind at the time of the initial interviews, the respondents regarded their commuter partnership as a household arrangement that was compatible with their lifestyle. This group of respondents is diverse; some had young children, others had teenagers at home, and others had recently become empty nesters or were voluntarily childless. The professions varied between private and public sector jobs and self-employment. Some were dual-career couples with both spouses deeply involved in their occupational careers; others were dual-earners who opted for the commuter partnership in order to combine a fulfilling occupational career for one (usually male) spouse with a preferred residential lifestyle for the family and a (part-time) job for the spouse who lived permanently in this location.

The follow-up survey showed that six of these seven couples were as yet continuing their commuter partnership, with roughly the same commuting rhythms of separate locations and being together. Apparently, these couples’ expectations about the future course of their commuter partnership had been accurate up to that moment. An important resemblance between these couples was their continuing positive attitude towards this household arrangement as a durable lifestyle. Each partner, male and female, in all these couples emphasized their mutual independence within the framework of their partnership and family, which was expressed in self-fulfilment in the occupational career or in the residential career. They declared during the interviews that the commuter partnership was qualitatively in no way inferior to a nuclear family situation. Rick,Footnote 1 for example, is a manager and father of two teenage children. Both he and his wife have rewarding jobs that they enjoy. Rick is away from the family for 4 days a week. Although he realizes that he sometimes misses out on events that are part of everyday family life, he remarks: “Of course, all kinds of things can happen, but a commuter partnership in itself is something I could continue for at least ten years, no problem whatever. (…) I truly say this without any reservations; I mean, it’s absolutely not a question of ‘hanging in there’ or something like that. It’s simply a deliberate choice. Yes.” Both Rick and his wife Paula point out that they would not have considered a commuter partnership when their children were younger because they expected the division of care tasks to be divided too uneven among them at that time. Other dual-career couples, however, did not regard having young children as an obstacle to avoid a commuter partnership at the cost of their individual career choices. This finding shows that, for some couples, the role of life plans and strategic life planning is an integral part of their partnership and they fit their household arrangement accordingly. These couples do not refer to a nuclear family as the ideal household arrangement; instead, they choose their household arrangement in order to enable each partner to realize individual preferences within the framework of the partnership and family.

There was one exception in this group of seven couples. This one couple had separated in the period between the interview and the follow-up survey. During the interviews, both partners had already expressed the view that the quality of their marriage had strongly deteriorated and neither of them looked forward any longer to spending time together. Thus for this couple the commuter partnership had become a prelude to divorce. They divorced when one of them found a new partner. Interestingly, this was the only couple of all 30 for whom the commuter partnership ended in the dissolution of the partnership even though several other couples in the study mentioned relational problems that in some cases related to their commuter partnership and in other cases existed before their commuter partnership. The follow up showed that these couples were among those who had reunited at their original family home. This indicates that, by and large, the commuter partnership is not to be regarded as a prelude to divorce.

Commitment to work

The second group of couples who had an unlimited time horizon in mind for their commuter partnership (also seven couples), did so from the rationale that they were strongly committed to their work and did not expect to find a job opportunity in one shared location in the near future that would be as fulfilling as their current employment. A number of these respondents indicated during the interviews that they did not even search for opportunities near one shared residential location, because they did not believe that such opportunities existed. These respondents had highly specialized professions, for instance in banking or academia, or were strongly committed to their specific employer for whom they had worked for a long time. Some of these couples had dependent children at home, others were childless. The difference between these work-oriented couples and the respondents described above who regarded their commuter partnership as part of their lifestyle can be found in the weight respondents put on the external circumstances that controlled their situation. These work-oriented couples regarded their dual-residence situation as a form of complying with circumstances they could not change, taking into account their commitment to their work which can be regarded as a self-induced restriction. Their motivation for applying an unlimited time horizon at the time of the interviews was grounded in the perception that their specific situation made the pursuit of a nuclear-family household arrangement very difficult, even though that was what they would prefer. Barry is a 42 year old expert in environmental policy in The Netherlands. His wife Lisa works as a multi-language translator for the United Nations in Switzerland. Lisa does not speak Dutch. The couple strongly prefers to live together in one residence, but their long time efforts to find two jobs in either The Netherlands or Switzerland have not paid off yet. This is partly due to their personal list of demands regarding the job opportunities. These complexities and contradictions are part of their stories. Barry mentions: “The goal is that we really choose for each other. That is the thought that keeps us going. It is a dream, ambition. If you didn’t have that dream or goal, than it wouldn’t last long, the partnership. (…) Well, there were other job opportunities, but those were not interesting, they didn’t give enough security, or they didn’t pay well enough, or they provided insufficient career perspectives for the future, or a combination of those aspects.”

The follow-up survey shows that, contrary to their own expectations, five couples (of the seven) terminated their commuter partnership as a result of changes in their circumstances, which were either personal or external. In one of these cases, the commuting partner took up a new job at the shared location, because of strong dissatisfaction with her former employer resulting from company reorganization. This couple thus initiated a change in their household arrangement themselves. In two couples, the commuting partner took up a new job at the shared location as a result of external circumstances, namely on the employer’s initiative. In both cases the employer no longer needed the respondent at the distant company location and initiated the commuting partner’s transfer back to an office in the vicinity of the family home. Two other couples reunited at the original shared location owing to the unforeseen personal circumstances of the protracted illness of one spouse. Several of the couples who had reunited mentioned that living together again full-time required some initial adjustments from both of them, but they pointed out that they had regained quality in their personal lives. Fiona decided to move back home after a company reorganization she was unhappy about. Instead, she now has her own business which is located in the near vicinity of the shared residence. Being back together again after 5 years of being in a commuter partnership, did have an impact on their daily lives. Fiona says: “To take each other into account again was a big change. That was something to get used to after five years of each having our own rhythm. We have to think in terms of ‘we’ again, instead of ‘I’ … [laughter] … Before, we only had to think ‘we’ during the weekends; now, all the time. But being back together is super.”

This feeling was true not only for the experiences of partnership and family, but also for their social lives and leisure-time activities. Ronald, for instance, worked as a manager in The Hague while his wife worked and lived in their shared home in a northern province of The Netherlands. In the initial interview he clearly remarked that he missed his social and leisure activities at the shared home, which he had to give up. At the time of the follow up the couple had reunited at the family home. Ronald remarked: “When I got back to [town of shared home] I immediately joined my old volleyball team and the church choir. Life has certainly gained in quality with those activities.”

Of the seven work-oriented couples who applied unlimited time horizons during the interviews, the two remaining couples were still in a commuter partnership at the time of the follow-up. Neither couple was particularly happy about this situation, but none of these respondents was willing to make personal sacrifices in the life domain of work in order to be able to live in one location, nor would any of them demand such a sacrifice from their spouse. Apparently, neither couple had encountered any external circumstances that would have enabled them to reunite in one shared home. The women felt more responsible for searching a job near their husbands than the men did the other way around. Although these women felt a responsibility for reuniting in one residence, they also wanted to protect their individual career preferences in the process. Beth, for example, is a lawyer in a small local firm in The Netherlands. She is in her fifties and her grown up children have moved out of the parental home. Several years earlier her husband Richard, who is a professor, chose for a career move to Switzerland. Although Richard respects Beth’s choice to stay in The Netherlands for her job, it goes without saying for both partners that Beth should be the one to relocate, not Richard. The objectives mentioned by Richard are that Switzerland is a beautiful country to live in. Beth’s rationale is that Richard is more of a career oriented person then she is, that Richard has higher financial earnings, and that she indeed likes Switzerland. Richard is very optimistic about Beth’s prompt move to Switzerland. Beth however, feels the weight on her shoulders. Her dilemma is whether to choose for her own career or for their shared wish to live as a nuclear household. A choice that, she feels, she has sole responsibility for. As a result, no changes are expected to happen any time soon. Beth remarks in the initial interview: “I’m working on some possible job opportunities over there, and if that works out I guess it will become easier to move over there. But at the moment I find it very hard to tell, because I enjoy my work a lot. I find it an enormous uncertainty to get into. (…) Well, for me it’s one big question mark actually. I’m not exactly sure. I don’t look too far ahead. If anything crosses my path, then that’s fine. And I have a vague idea, but that is more emotional, of doing this for two more years or so. But, I think I also said that last year and the year before…”. The follow-up with this couple took place 2.5 years after the interviews. At that time nothing major had changed for this couple. Beth again mentioned that she would move to Switzerland at some point in the future.

Couples with a limited time horizon

At the time of the interviews, there were also respondents who had in mind limited time horizons for the future duration of their commuter partnership. Some expected to be reuniting in one location within a year; others expected their commuter partnership to last for several years to come, but not for an unlimited period of time. For many of these couples, the time horizon was related to the circumstances under which they had started commuting. For one group, the appointment periods of job contracts were decisive in their expectations for the future; for another group of respondents, the anticipation of future life-course transitions was fundamental.

Temporary jobs

In the first group of couples who had limited time horizons in mind, the interviews showed that temporary job appointments provided the main rationale for choosing a commuter partnership and ruling out family migration (nine couples). Most of them, some with children at home, were dual-career couples for whom the (permanent) job of one partner at the shared location provided the rationale not to migrate for a temporary employment opportunity for the other spouse. Some others mentioned that the stability of the school-going children and their social attachment to a specific town was an essential aspect of the choice not to migrate for the temporary job opportunity of one partner. When the temporary job was located outside The Netherlands, this was a particularly strong reason to avoid family migration and opt instead for one spouse to become a ‘part-time expatriate’.Footnote 2 All these couples knew at the time of the interviews that there was a reasonable chance that they would extend their temporary period of working away from the shared home by an additional term. Many were led in the plan to evaluate their experience with the commuter partnership shortly before the end of the first term. Delia, for instance, works in Brussels in EU politics. She has two daughters, one of whom still lives in the parental home in Amsterdam. Delia’s husband Stefan works in Amsterdam as a lawyer. Both of them have officially cut down on their work hours to have enough time for their care responsibilities. However, by compressing her work week through working extra hours in the evenings, Delia carries a full work load. In the initial interview Delia remarked: “If I got the feeling that my husband was not completely happy with the situation, then it would become a different experience for me too. And yes, that is very important for the balance in the situation. I feel it is a great commitment. Next year I will have to consider carefully whether to opt for another term, precisely because again it is a commitment for four years. And just as it was when we first took the decision, again it will depend on whether the whole picture looks as though we can or cannot do this for another period.” From the follow-up, 2 years later, it became clear that Delia signed on for a second term. Furthermore, the couple had become empty nesters in the meantime and both spouses had decided to increase their work hours. The couple pointed out again that they would reconsider their situation when Delia’s second term in Brussels would come to an end. This finding shows that the growing importance of temporary job contracts as part of today’s flexible economy has distinct impacts on the household arrangements and life planning of individuals, couples, and families.

The follow-up survey showed that five of these nine couples had continued their commuter partnerships, similar to Delia and Stefan. The commuting partner in each of these couples worked either in a national governmental organization located in The Hague in The Netherlands, or in the context of the European Union in Brussels, for instance as members of the European Parliament or on the boards of directors of non-governmental organizations associated with European politics. The personal responsibility for living up to the trust put in them by their electors provided the drive to commit to the commuter partnership. This result illustrates the growing importance of an attitude of personal responsibility and commitment to the work career, especially among specialized professionals; an attitude that prevails even if a person has to pay the price in the private domains of life. These five couples all opted to run for a second term in office. Some couples mentioned that they actually had evaluated their past experiences with the commuter partnership before committing themselves to an additional period of another 2–5 years. Others reported that they had refrained from their initial plan to evaluate their experiences and automatically continued their commuter partnership. Their strong work commitment and their positive experience with the commuter partnership made this continuation a logical choice.

Four other couples (of the nine) who had limited time horizons in mind owing to temporary jobs had decided not to continue their commuter partnership. The commuting partners in these couples had been in appointed (not elected) temporary jobs. Even though they also had the prospect of another term of working at the company location away from the family home, each of these respondents had declined that opportunity and reunited in the family home. All four of these couples had a similar of motivation for not continuing their commuter partnership, which was grounded in the experience of their partnership and family life. One respondent remarked: “I missed my wife” (Kevin), another pointed out: “I felt too far removed from my family” (Keith). This response shows that the flexible economy with its temporary jobs can be experienced by individuals and couples as a burden on the life domains of partnership, family, and residence. As these couples show, for some this burden results in making concessions in their occupational careers in order to preserve the quality of their private lives.

Anticipation of future life-course transitions

A second group of couples who had limited time horizons in mind at the time of the interviews held these views in anticipation of expected life-course transitions (seven couples). The events these couples anticipated were either family formation (marriage and having children) or retirement from the workforce.

Four couples were anticipating family formation at the time of the initial interview. These couples were in their late twenties or early thirties and envisaged reunion in one location in the near future, because they preferred a nuclear family setting when they had children. These couples were found to employ significantly shorter time horizons for their commuter partnership than most other couples. They expected to be living in one shared home again within about a year. The follow-up survey showed that all four of these couples had reunited in a new family home and in the intermediate period they had either married or had their first child. Three of these couples were currently living as expatriates outside The Netherlands, which had required one partner of each couple (two female partners and one male partner) to give up their job in The Netherlands in order to join their partner as a trailing spouse. All three trailing spouses had in the meantime found some form of paid work, but not (yet) at the same intellectual or remuneration level as they had had before. This finding confirms the family migration theory on the losses in the occupational careers and income levels of trailing spouses. For some couples the commuter partnership can function as an arrangement to put off a tied move for one of both partners. The findings also show how the commuter partnership can be useful arrangements in certain phases of the life course, or to bridge certain intermediary periods in the life course. Caroline and Dan are a good example. At the time of the initial interviews they were in their late twenties and both opted to give priority to their individual work careers as yet. Family formation was an issue for the future to them. Caroline remarked: “I think that if we had had children, this commuting would not have happened at this moment. I mean, in that event he would have had to say: no, I’m not going. Or I would have had to say: then I will go with you. (…) It is like, if you have children, then you want to be there to raise them together. And to carry that responsibility together.” The follow-up disclosed that after one and a half years of living as a commuter couple, Caroline and Dan had married and Caroline had moved to London to live with Dan. Caroline had found a new job over there but took a loss of income. The couple mentioned: “In case it should be necessary for work, the realizations of dreams, or our family situation, we are willing to start a commuter partnership again. The period of dual residences should not be too long however, it should be an overseeable period.”

Among the couples who employed temporary time horizons because of expected life-course events, retirement was the key factor for three other couples. In one case, at the time of the interview the retirement of the male spouse was imminent, and the follow-up showed that he had indeed joined his wife in their family home, from which she continued to commute to work daily. Two other couples used their future retirement as the time horizon for ending the commuter partnership, even though at the time of the interview the retirement was still 5–10 years away. Evidently, some individuals start to anticipate the end of the working career a considerable period ahead of their retirement, which leads to long, but well-defined time horizons for future events in the life course. As expected, these couples had not yet retired at the moment of the follow-up. However, some unexpected changes had occurred for both couples. The male spouse in one couple had recently been made redundant through his company’s reorganization. This situation had led to an unexpectedly early reunion in the family home. The last couple, Theo and Flora, had started commuting after they had become empty nesters and experienced their commuter partnership as a renewed life style that fitted this life-course period in a positive way. They were continuing their commuter marriage at the time of the follow-up, even though Theo had changed to another job and Flora had cut her workload. The commuter partnership enabled Flora in particular to pursue her individual preferences at long last, without harming the common interests of the family or the wellbeing of the children. Flora remarked: “Well, I’m someone who always joined my husband to move for his job. After our last move I did think later on that that wasn’t a good decision, and then I decided not to do that anymore, to join my husband as a dependent. (…) At the same time that I started living here I changed some other things. We had been married for twenty-five years, the kids had moved out, and I started using my maiden name again…” For this couple the commuter partnership had developed into a household arrangement that they continued after the work related necessity for two residential locations was no longer there. From a commuter partnership it had developed in a Living-Apart-Together partnership, in which both partners valued the sense of independence that resulted from living in two separate locations for several days a week. However, the couple intended to join up in one shared home after their retirement. Thus they regarded their dual location household arrangement still as a temporary alternative to a nuclear household arrangement.

The experiences of respondents who had limited time horizons in mind in anticipation of future life course transitions demonstrate that, for many couples, a commuter partnership as an alternative to a nuclear family is an option in those phases of the life course when there are no dependent children. In such periods, these couples find that they can each pursue individual preferences without harming the common interests of family and children. This view contrasts with the views of other commuter couples that a commuter partnership is a perfectly suitable alternative household arrangement, also when there are children in the household.

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to gain a better understanding of the sustainability of commuter partnerships and to contribute to uncovering the function that this household arrangement can have in the coordination of parallel careers of different household members over time. In order to reach this objective, we interviewed both partners in 30 commuter partnerships about their plans and expectations and contacted the same 30 couples once more 2–4 years later. By that time, eleven couples had reunited in their original family home, for four couples the commuter partnership had resulted in family migration, fourteen other couples were as yet continuing their commuter partnership, and one couple had separated. Taking into account the limitations of our sample, our findings indicate that a significant share of couples who start commuter partnerships continue this household arrangement for the medium or long term in order to ensure that neither partner has to take on the role of either trailing spouse or tied stayer. In that sense, the commuter partnership can be understood as a form of instrumental behaviour to avoid the complexities for individual careers connected with tied moves or tied stays. Sometimes a tied move or tied stay is avoided altogether; in other instances it is only delayed by opting for a commuter partnership. Our findings further indicate that the commuter couples who return to a nuclear household arrangement are more likely to reunite in the original family home than to migrate to the new location. This finding also points toward the conclusion that a commuter partnership should not in general be regarded as a prelude to family migration, but rather as a household arrangement that avoids family migration altogether, either for a limited period or for the longer term. Further quantitative longitudinal survey work on this household arrangement could create more insights into the incidence and sustainability of commuter partnerships.

In order to understand why some commuter partnerships last for many years and others are terminated after a couple of years, we looked into each couple’s rationale for continuing or terminating their commuter partnerships. Couples either adopted limited time horizons for the future duration of their commuter partnership or they applied unlimited time horizons. There appear to be distinct differences between the couples that emphasize how their commuter partnership fits in with their individual preferences and the couples whose motivations for the commuter partnership were predominantly led by external circumstances. Among those who reasoned that their commuter partnership resulted from their individual choice options, in general, couples envisioned the future duration of their commuter partnership quite accurately. These are the couples who look at the commuter partnership as a lifestyle, which they expected to be sustainable for many years, and the couples who have limited time horizons in mind because they are anticipating future transitions in their individual life courses. Interestingly, the views of these two types of couples on the longer term sustainability of the commuter partnership as an alternative household arrangement to the classic nuclear family were different. The former group regarded the commuter partnership as a sustainable household arrangement in itself; the latter group regarded the commuter partnership as a reasonable alternative to the nuclear family in phases of the life course when the common interests of the family (that is, the children) were not harmed.

In contrast with the groups of commuter couples described above, the couples whose choice of the commuter partnership was largely guided by the external circumstances of their jobs showed more diversity in the accuracy of predicting the future duration of their commuter partnerships. In the case of commuter couples who have unlimited time horizons in mind because of a permanent job contract, different kinds of circumstances were found to be decisive in the sustainability of the commuter partnership. The unforeseen termination of a job contract or illness are examples of circumstances that can lead to the termination of a commuter partnership, and a lack of personal initiative to find a job closer to home can lead to long-term continuation. For the couples with limited time horizons owing to temporary job contracts, we found a striking division in the sustainability. On the one hand were those couples who were highly motivated for their elected positions and who had opted for a second term of commuting, which probably relates to these individuals’ dedication to their jobs. On the other hand were the couples who had decided to try a commuter partnership during a well-defined period for a temporary job opportunity, but who decided on the basis of personal experience that they did not wish to continue a commuter partnership and made sure that they found alternative jobs near their family home.

Our study shows that the contingency of the life course and the predictability for individuals about their own future life courses is clearly influenced by external circumstances and societal change. In that respect, economic globalization and flexibilization influence the life courses of individuals, couples, and families. The individualization that characterizes late modern society also impacts significantly on the life courses of commuter couples; the search for balance between individual preferences and common interests of the household is an ongoing process for these couples. Furthermore, the notions of risk, of personal resources and restrictions, and the limitations these encompass for family-life planning are relevant in the predictability of life courses. As our results show, unexpected events such as illness or unemployment impact heavily on the continuity of life courses, as do changes in the household composition. Some of these events are more common than others, but they can all impact severely on couples when they do occur. Notwithstanding the risks involved, the commuter partnership can facilitate couples and families in seizing more opportunities for individual self-realization, especially in the domain of work. In that sense, the contingent life course is an integral part of life, because it demands continuous evaluation and adaptation to changing circumstances and opportunities. The impact is not only on occupational careers, but also on the life domains of residence and family.

Notes

The interviews have been rendered anonymous to protect the privacy of the respondents.

A number of publications, newspaper articles and websites report the growing amount of ‘part-time expatriates’, especially between Europe’s capital cities (see for instance: www.expatica.com). Such part-time expatriate arrangements are on the one hand induced by employers as a cost-saving measure (compared with classic expatriate family arrangements in which the expenses are far higher). On the other hand part-time expatriatism is preferred by a growing number of employees who are in dual-career partnerships in which both partners are committed to their occupational careers and not willing to follow each other as a trailing spouse to another country at the cost of their own career. Furthermore, budget airlines and high speed rail travel opportunities add to the accessibility and the affordability of international commuting.

References

Bailey, A. J., Blake, M. K., & Cooke, T. J. (2004). Migration, care, and the linked lives of dual-earner households. Environment & Planning A, 36(9), 1617–1632. doi:10.1068/a36198.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society. Towards a new modernity. London: Sage Publications.

Berelson, B., & Steiner, G. A. (1964). Human behavior: An inventory of scientific findings. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (1992). I will follow him: Family ties, gender-role beliefs, and reluctance to relocate for a better job. American Journal of Sociology, 97(5), 1241–1267. doi:10.1086/229901.

Boyle, P., Cooke, T. J., Halfacree, K., & Smith, D. (2001). A cross-national comparison of the impact of family migration on women’s employment status. Demography, 38(2), 201–213. doi:10.1353/dem.2001.0012.

Boyle, P., Halfacree, K., & Robinson, V. (1998). Exploring contemporary migration. Harlow: Longman.

Brannen, J., & Nilsen, A. (2005). Individualisation, choice and structure: A discussion of current trends in sociological analysis. The Sociological Review, 53(3), 412–428. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00559.x.

Clark, W. A. V., & Huang, Y. (2006). Balancing move and work: Women’s labour market exits and entries after family migration. Population Space and Place, 12, 31–44. doi:10.1002/psp. 388.

Cooke, T. J. (2003). Family migration and the relative earnings of husbands and wives. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. Association of American Geographers, 93(2), 338–349. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.9302005.

Cooke, T. J., & Bailey, A. J. (1996). Family migration and the employment of married women and men. Economic Geography, 72, 38–48. doi:10.2307/144501.

Degler, C. N. (1980). At odds: Women and the family in America from the revolution to the present. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dieleman, F., & Musterd, S. (Eds.). (1992). The Randstad: A research and policy laboratory. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(1), 4–15. doi:10.2307/2786971.

Fagnani, J. (1993). Life course and space. Dual careers and residential mobility among upper-middle-class families in the Ile-de-France region. In C. Katz & J. Monk (Eds.), Full circles. Geographies of women over the life course (pp. 171–187). London: Routledge.

Gerstel, N., & Gross, H. (1984). Commuter marriage. A study of work and family. New York: Guilford Press.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine.

Green, A. E., Hogarth, T., & Shackleton, R. E. (1999a). Long distance living: Dual location households. Bristol: Policy Press.

Green, A. E., Hogarth, T., & Shackleton, R. E. (1999b). Longer distance commuting as a substitute for migration in Britain: A review of trends, issues and implications. International Journal of Population Geography, 5, 49–67. doi :10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199901/02)5:1<49::AID-IJPG124>3.0.CO;2-O.

Halfacree, K. H., & Boyle, P. J. (1993). The challenge facing migration research: The case for a biographical approach. Progress in Human Geography, 17, 333–348. doi:10.1177/030913259301700303.

Hardill, I., Green, A. E., & Dudleston, A. C. (1997). The ‘blurring of boundaries’ between ‘work’ and ‘home’: Perspectives from case studies in the East Midlands. Area, 29(4), 335–343. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.1997.tb00035.x.

Haskey, J. (2005). Living arrangements in contemporary Britain: Having a partner who usually lives elsewhere and living apart together (LAT). Population Trends, 122, 35–45.

Heinz, W. R., & Krüger, H. (2001). Life course: Innovations and challenges for social research. Current Sociology, 49(2), 29–45. doi:10.1177/0011392101049002004.

Hitlin, S., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170–191. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2007.00303.x.

Hochschild, A. R. (1997). The time bind. When work becomes home & home becomes work. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Jacobsen, J. P., & Levin, L. M. (1997). Marriage and migration: Comparing gains and losses from migration for couples and singles. Social Science Quarterly, 78(3), 688–709.

Jarvis, H. (1999). The tangled webs we weave: Household strategies to co-ordinate home and work. Work Employment and Society, 13(2), 225–247.

Karsten, L. (2003). Family gentrifiers: Challenging the city as a place simultaneously to build a career and to raise children. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 40(12), 2573–2584. doi:10.1080/0042098032000136228.

Liefbroer, A. C., & Dykstra, P. A. (2000). Levenslopen in verandering. Een studie naar ontwikkelingen in de levenslopen van Nederlanders geboren tussen 1900 en 1970. (Changing life courses. A study into the developments in life courses of Dutch born between 1900 and 1970). Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Mincer, J. (1978). Family migration decisions. The Journal of Political Economy, 86, 749–773. doi:10.1086/260710.

Moen, P., & Wethington, E. (1992). The concept of family adaptive strategies. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 233–251. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001313.

Mulder, C. H. (1993). Migration dynamics: A life course approach. Amsterdam: Thesis Publishers.

Mulder, C. H., & Hooimeijer, P. (1999). Residential relocations in the life course. In L. J. G. Van Wissen & P. A. Dykstra (Eds.), Population issues an interdisciplinary focus (pp. 159–186). New York, N. Y.: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Murdock, G. P. (1965). Social structure. London/New York: MacMillan/The Free Press.

Musterd, S., Bontje, M., & Ostendorf, W. (2006). The changing role of old and new urban centers: The case of the Amsterdam region. Urban Geography, 27(4), 360–387. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.27.4.360.

Portegijs, W., & Keuzenkamp, S. (Eds.). (2008). Nederland deeltijdland. Vrouwen en deeltijdwerk (Women and part-time employment in The Netherlands). Den Haag: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau.

SCP., & CBS. (2006). Emancipatiemonitor 2006. The Hague: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau/ Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Sennett, R. (1998). The corrosion of character. The personal consequences of work in the new capitalism. New York: Norton.

Shihadeh, E. S. (1991). The prevalence of husband-centered migration: Employment consequences for married mothers. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 432–444. doi:10.2307/352910.

Smits, J. (1999). Family migration and the labour-force participation of married women in The Netherlands, 1977–1996. International Journal of Population Geography, 5, 133–150. doi :10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199903/04)5:2<133::AID-IJPG135>3.0.CO;2-L.

Valentine, G. (1999). Doing household research: Interviewing couples together and apart. Area, 31(1), 67–74. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.1999.tb00172.x.

Van de Kaa, D. J. (1994). The second demographic transition revisited: Theories and expectations. In G. Beets (Ed.), Population and family in the low countries 1993: Late fertility and other current issues (pp. 81–126). Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Van der Klis, M., & Mulder, C. H. (2008). Beyond the trailing spouse: The commuter partnership as an alternative to family migration. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 23(1), 1–19. doi:10.1007/s10901-007-9096-3.

Van Ham, M., Hooimeijer, P., & Mulder, C. H. (2001). Urban form and job access: Disparate realities in the Randstad. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 92(2), 231–246. doi:10.1111/1467-9663.00152.

Van Ommeren, J. (2000). Job and residential search behaviour of two-earner households. Papers in Regional Science, 79, 375–391. doi:10.1007/PL00011483.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Klis, M. Continuity and change in commuter partnerships: avoiding or postponing family migration. GeoJournal 71, 233–247 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9159-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-008-9159-3