Abstract

Dietary manipulation of animal diets by reducing crude protein (CP) intake is a strategic NH3 abatement option as it reduces the overall nitrogen input at the very beginning of the manure management chain. This study presents a comprehensive meta-analysis of scientific literature on NH3 reductions following a reduction of CP in cattle and pig diets. Results indicate higher mean NH3 reductions of 17 ± 6% per %-point CP reduction for cattle as compared to 11 ± 6% for pigs. Variability in NH3 emission reduction estimates reported for different manure management stages and pig categories did not indicate a significant influence. Statistically significant relationships exist between CP reduction, NH3 emissions and total ammoniacal nitrogen content in manure for both pigs and cattle, with cattle revealing higher NH3 reductions and a clearer trend in relationships. This is attributed to the greater attention given to feed optimization in pigs relative to cattle and also due to the specific physiology of ruminants to efficiently recycle nitrogen in situations of low protein intake. The higher NH3 reductions in cattle highlights the opportunity to extend concepts of feed optimization from pigs and poultry to cattle production systems to further reduce NH3 emissions from livestock manure. The results presented help to accurately quantify the effects of NH3 abatement following reduced CP levels in animal diets distinguishing between animal types and other physiological factors. This is useful in the development of emission factors associated with reduced CP as an NH3 abatement option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Livestock is a mainstay of global food supply and the agricultural economy. It accounts for 10–15% of total food calories and a quarter of the dietary protein consumed around the world (FAO 2011). It also contributes to 36% of the value of world agricultural output and is a source of livelihood for around 1.3 billion people (Thornton 2010; FAO 2011). It is one of the fastest growing segments of the agricultural sector, especially in developing countries. With rapid urbanization, rising incomes and the emergence of the middle class, the global demand for livestock products is projected to increase in the coming decades (Gerber et al. 2013). Meeting this demand is an immense challenge for agricultural production, but it also poses a significant threat to the environment.

Numerous studies have highlighted the negative externalities associated with the expanding livestock sector, particularly in terms of ammonia (NH3) emissions. In 2014, livestock rearing and production contributed two thirds of the total agricultural NH3 emissions in the 28 member countries of the European Union (EU-28) (UNECE 2016). NH3 is an air pollutant and is detrimental to human health, as it contributes to the formation of particulate matter in the atmosphere (Malek et al. 2006). Increased NH3 emissions lead to eutrophication in lakes and rivers and acidification of soils. Additionally NH3 emissions constitute a loss in nitrogen (N), which could have been a source of fertilizer when applied to the soil (Sutton et al. 2011). Hence, the abatement of NH3 emissions from livestock rearing and production is imperative.

There are various sources of NH3 emissions within the livestock sector. Among these sources, the most prominent are the emissions associated with manure management. Emissions from manure management as defined here encompass emissions from animal housing systems, handling and storage of manure, deposition of manure during grazing and also from the application of manure as a fertilizer to soils. These emissions cover almost all of the total livestock NH3 emissions in the EU-28 (UNECE 2016). A number of policies have been implemented to tackle NH3 emissions from the agricultural sector including those from manure management in Europe, especially among the countries in the European Union. These policies impose emission ceilings, monitor and review agricultural practices and also recommend usage of best available techniques (BAT) to reduce agricultural emissions. The objectives, structure and implementation of these policies are guided by published literature, underlining their role in the policy making process. As far as emissions from manure management are concerned, various studies have described and quantified the potential of abatement options to reduce NH3 emissions (Bittman et al. 2014). These studies are valuable in estimating the emission reduction potentials of abatement options and help design strategies aimed at reducing NH3 emissions.

The manipulation of crude protein (CP) in animal diets is one such abatement technique to reduce NH3 emissions from manure management. Animal diet manipulation is a strategic abatement option, since it alters the manure characteristics right at the source and reduces overall nitrogen input. Other abatement options reduce emissions at a particular stage, but do not avoid excess nitrogen input. Changing animal diets has an effect on the whole manure management chain, irrespective of which stage the emissions are measured (Chadwick et al. 2011).

CP is generally incorporated in animal diets to ensure animal growth and maintain bodily functions (van Vuuren et al. 2015). N is a basic component of CP and constitutes around 16% of its mass. While a portion of the ingested protein N is used by the animal to produce meat, milk, eggs, body tissues and offspring, a large percentage is excreted as faeces and urine. N in faeces is mainly in the form of organic compounds and is less prone to losses via volatilization as NH3. Urine on the other hand, contains N in the form of urea which, when exposed to bacterial urease, is easily transformed to NH3. This has been highlighted in many studies which report that the presence of nitrogenous compounds (primarily as urea in urine) along with a high manure pH are the main factors leading to NH3 emissions from manure (Lynch et al. 2007; Feilberg and Sommer 2013). The potential of reduced CP in animal diets to decrease both the amount of N and pH of manure has been demonstrated in various studies (Canh et al. 1998; Lynch et al. 2007; Le et al. 2009). Due to concerns of farmers regarding animal productivity and also due to the safety margins implemented by the feeding industries, dietary CP is usually fed in excess of what is required by the animals. This oversupply of CP leads to a greater percentage of N in manure, and a subsequent increase in NH3 emissions (van Vuuren et al. 2015). Research has shown that it is possible to reduce dietary CP in animal diets without affecting animal performance and health, resulting in lower NH3 emissions (Hansen et al. 2007; Agle et al. 2010; Arriaga et al. 2010). This has been made possible by carefully matching the diets with the requirements of the animals. In the case of monogastrics such as pigs, exogenous supplementation of essential amino acids also helps in achieving the required intake of essential amino acids while simultaneously reducing protein intake. This supplementation improves N utilization and reduces N excretion, once again resulting in reduced NH3 emissions (Panetta et al. 2006; Madrid et al. 2013; Montalvo et al. 2013). Acknowledging this potential, Annex IX to the Gothenburg protocol recommends reducing CP in animal diets to abate NH3 emissions (UNECE 2015). Reduction of CP in animal diets is also mentioned in the recent guidance document on NH3 abatement as one of the most cost effective and strategic ways to reduce NH3 emissions (Oenema et al. 2014).

NH3 emission reductions from dietary manipulation of animal diets have been quantified using measured and reported NH3 emissions from experimental studies (Oenema et al. 2014; Hou et al. 2015). Although these results are very useful, they suffer from some drawbacks. Firstly, these quantifications are based on studies that measure the impacts of reduced CP on NH3 emissions for different animal types (e.g., pigs, cattle) and categories (e.g., gilts, barrows, boars, etc.) (Hansen et al. 2007; Le et al. 2009; Arriaga et al. 2010). Furthermore, emission reductions are reported at different stages of the manure management chain (Portejoie et al. 2004; Madrid et al. 2013) and vary in initial and final CP levels from and to which CP is reduced (Portejoie et al. 2004). NH3 emissions reductions from reduced CP have not been analysed in light of these factors which lends considerable variability to the reported emission reduction estimates. Hence, even though these studies are helpful in understanding NH3 emission patterns with reduced CP, simply aggregating emission reduction estimates will likely lead to a gross misrepresentation of the overall reduction potential of reduced CP as an NH3 abatement option. This highlights the need to better quantify the influence of reduced CP on NH3 emissions, while distinguishing for animal types and also accounting for other factors which may influence NH3 emissions. Such an analysis has not been conducted in previous literature.

The present study aims to address this research gap by presenting a comprehensive analysis of NH3 emission reductions from lowering CP content in animal diets. The results discussed here examine the relationship between reduced CP and NH3 emissions for both cattle and pigs. The results also explore the effect of reduced CP on total ammoniacal nitrogen (TAN) and of the initial and final CP levels on NH3 emission reductions. Furthermore, the study also analyses the effect of factors such as manure management stages and animal categories on NH3 emission reductions.

Methodology

Meta-analysis is a technique used to combine the results from several scientific studies (Kim et al. 2012, 2013; Patra 2013). The study presented here uses a meta-analysis to quantify and compare the effect of a reduction in CP on NH3 emissions for both cattle and pigs. A meta-analysis constitutes the following key elements (Rosenthal 1985; Sauvant et al. 2008): (1) inclusion criteria, (2) literature search and selection of data sources, (3) estimation of effect size, and (4) statistical analysis. These elements were employed in this study and are described below.

Inclusion criteria

Animal husbandry and related human activities are sources of many different pathways of NH3 fluxes to the atmosphere. In this paper, we focus on the activities that concern the management of cattle and pig manure. Since a reduction of CP content in animal diets affects all phases of the manure management chain, we consider emissions from urine and faeces excreted in animal housing, during their storage, and their application to agricultural soils. Emissions from manure deposited during grazing are not included in this study. Grazing emissions are common in cattle production systems which often include pasturage, but reduced CP as an NH3 abatement option is not feasible in such cases since it is difficult to ascertain the amount of CP in the diet and set reduction targets as compared to housed animals. Moreover, the NH3 emissions from grazing animals are relatively lower than housed animals, since urine, the primary source of NH3 emissions seeps into the soil on contact (Oenema et al. 2014).

Selection of data sources

Google Scholar was used to search the literature for studies pertaining to NH3 emissions from a reduction of CP in animal diets. The relevant data sources were then chosen in line with selection criteria described in recent studies that focus on emission reductions in manure management (Hou et al. 2015, 2017; Wang et al. 2017). The selection criteria were as follows: (1) the animal type was either cattle or pigs subject to reduced CP in their diets; (2) NH3 emissions were measured and reported in at least one of the following manure management stages: housing, storage or application; (3) reference treatments included initial and final CP levels along with reference NH3 fluxes; (4) studies complied with standards related to animal nutrition and experimental design; (5) the articles were peer reviewed and available in English. The selection criteria resulted in a selection of 22 individual studies measuring NH3 emissions under reduced CP comprising measurements from on-farm and simulated farm settings conducted in Europe or North America. This consisted of eight studies for cattle and 14 for pigs amounting to 67 unique NH3 measurements. In addition to NH3 emissions, TAN content of the manure was also extracted from the studies when available. Related information such as study location, emission measurement technique, animal category, feed type and manure characteristics were also compiled and catalogued (see Table S.1 and S.2 in the supplementary information). Differences between studies that could affect NH3 emission reductions such as measurement of emissions at different manure management stages and across animal categories were identified and their implications on NH3 emission reductions were investigated. Other possible sources of variability such as differences in manure management systems, the type of protein sources and physiological stage of animals were also considered, despite the fact that a statistical analysis was not possible due to insufficient data. Variation in NH3 emissions arising from location, animal production systems, measurement techniques etc. can also influence the reported emission reduction estimates. However, this uncertainty in emission reduction estimates cannot be handled with current knowledge since livestock production is complex in nature and varies between countries and production systems (Stewart et al. 2009; Crosson et al. 2011; Loyon et al. 2016). Currently no standard methodology exists to evaluate the quality, representativeness and transitory nature of emission data pertaining to livestock production systems.

Estimation of emission reduction potentials

Effect sizes were represented as NH3 emission reductions which were estimated using observations from the selected studies. The emission reductions were calculated relative to the NH3 emissions during reference CP treatments using Eq. (1).

where Ea is the NH3 emission reduction (%); Ercp is the NH3 emission after reduced CP treatment; Eref is the NH3 emissions during reference treatment. The units of Ercp and Eref are dependent on the units used in individual measurement studies. A positive value of Ea indicates a decrease in NH3 emissions. This allowed for a simple normalization of emission measurements in percentage terms, prior to averaging them. Emissions were also expressed in terms of an absolute change in percentage CP. The difference between initial and final CP, both given in percent, is defined as %-point reduction (e.g., a change from a CP content of 16.5 to 15.5% is regarded a reduction of one %-point). Tables 1 and 2 report all the studies that were used to calculate NH3 emission reductions for both pigs and cattle respectively. The effect of CP changes on TAN reductions was calculated in the same way as for NH3 emissions when data were available.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis of emission reductions was performed to estimate the mean emission reductions along with the standard deviation (SD), sample size, maximum and minimum values. Regression analysis was used to determine the relationships between NH3 emission reductions, TAN reductions and the CP traits (CP reductions, initial CP and final CP levels) along with their associated interactions. Three models were tested for cattle and pigs separately to understand whether statistically significant relationships exist between Model 1 (p = pigs, c = cattle): CP traits and NH3 reductions; Model 2 (p and c): CP traits and TAN reductions; Model 3 (p and c): TAN reductions, final and initial CP on NH3 reductions. As CP reduction, initial CP and final CP are linearly dependent, only two of these CP traits can be used in the same model. This leads to four different combinations within a model for each combination of CP traits that needs to be compared. However, since initial and final CPs cannot be included without the main effects—CP reductions and TAN reductions, only three combinations were considered. The criterion for the best suited model was the highest adjusted R2. All regression analyses and selections were done with the REG procedure in the statistical software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A fixed-effect analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was fitted to combine the data of the two species, pigs and cattle, with the aim to test if there were differences between the species with respect to NH3 emission reductions. In addition, the models were also tested to check if measurement stage and animal category were significant in explaining NH3 emission reductions. For comparison between the models the SD of the residuals was considered, with the better fit indicated by a lower SD. All ANCOVA models were analysed with the MIXED procedure of SAS 9.4. All factors were tested at a significance level of 0.05. Differences between class levels of significant factors were tested in post hoc t tests. When interactions between class effect and regression effect were significant, differences were tested at a range of values of the dependent variable to identify ranges where the class factors are different. For multiple pairwise comparisons between least squares means, the “simulate” option was used to keep the global significance level of 0.05.

Results

Relationship between CP traits, TAN and NH3 emissions for pigs

Descriptive statistics of NH3 emissions with reduced CP in pig diets show average NH3 reductions of 38 ± 19% (n: 47, Max: 76%, Min: 0%). Averaging the emission reductions over a %-point reduction in CP shows a 11 ± 6% (n: 47, Max: 32%, Min: 0%) decrease in NH3 emissions. Testing the relationship of NH3 reductions with CP traits indicates an influence of CP reduction, final CP and an interaction between CP reduction and final CP at an adjusted R2 of 0.53 (RMSE = 13.54). In the final model, only CP reduction and the interaction between CP reduction and final CP were statistically significant (p < 0.05). However, since the interaction terms cannot be included without the main effect, final CP was part of the model as well.

where Ea is the NH3 reduction (%); CPred is the CP reduction (%-point); Fcp is the final CP level (%).

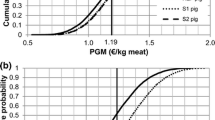

Figure 1 illustrates Model 1 [p] and shows that high reductions of NH3 can be achieved when the final CP level is low and the reductions in CP are high. Descriptive coefficients of the emissions estimates indicate that reduced CP in pig diets led to reductions of TAN by 34 ± 16% (n: 34, Max: 64%, Min: 3%). Average reductions in TAN per %-point reduction in CP was 8 ± 3% (n: 34, Max: 13%, Min: 1%). Investigating the effect of CP traits on TAN reductions through a regression analysis indicates an influence of CP reduction and final CP at an adjusted R2 of 0.56 (RMSE = 12.81). All the factors included in the model were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

where TANred is the TAN reduction (%).

Testing for whether TAN is the primary driver of NH3 emissions reveals a similar relationship to that of CP traits and NH3 reductions as in Model 1 [p]. The final model chosen includes TAN reductions, final CP and the interaction of TAN reductions with final CP at an adjusted R2 of 0.58 (RMSE = 12.81). Only TAN reductions and the interaction between TAN reductions and final CP were statistically significant (p < 0.05). However, since the interaction term is significant, the main effect had to be added to the final model.

NH3 emission reductions also varied based on the manure management stage at which they were measured. Estimates from a descriptive analysis of the observations show reductions of 11 ± 6% (n: 26, Max: 32%, Min: 1%) for housing, 6 ± 5% (n: 5, Max: 13%, Min: 1%) for storage and 7 ± 7% (n: 3, Max: 13%, Min: 0%) for application when averaged over a %-point reduction in CP. Differences in NH3 emission reductions also existed between pig categories. Gilts and barrows had NH3 reductions of 12 ± 7% (n: 22, Max: 32%, Min: 0%), whereas boars showed reductions of 7 ± 5% (n: 11, Max: 18%, Min: 1%) when averaged over a %-point reduction in CP. The ANCOVA method was used to test the influence of manure stages and animal category on the extent of NH3 reductions from reduced CP using the best fitted Model 1 [p]. The analysis showed that although there were variations in emission estimates, no statistically significant difference exists to indicate that measurement stage and animal category influence NH3 emission reductions.

Relationship between CP traits, TAN and NH3 emissions for cattle

Descriptive statistics of NH3 emission reduction estimates for cattle with reduced CP report average emission reductions of 43 ± 18% (n: 20, Max: 73%, Min: 4%). The average emission reductions per %-point CP reductions show a decrease in NH3 emissions by 17 ± 6% (n: 20, Max: 30%, Min: 4%). Testing for the relationship between CP traits and NH3 emissions reveals a close relationship between NH3 emissions and CP reduction with an adjusted R2 of 0.80 (RMSE = 8.46, p < 0.05).

Figure 2 illustrates this relationship and shows that greater reductions of NH3 can be achieved at high CP reductions. Contrary to the case in pigs, there was no influence of final CP on NH3 emission reductions. TAN content of manure also decreases with a reduction of CP in cattle diets. A descriptive statistical analysis of TAN estimates show reductions of 38 ± 21% (n: 16, Max: 74%, Min: 0%) and 15 ± 6% (n: 16, Max: 27%, Min: 0%) when averaged over a %-point reduction in CP. Testing the relationship of TAN reductions with CP traits revealed a strong relationship with TAN and CP reduction at an adjusted R2 of 0.80 (RMSE = 8.46, p < 0.05).

Investigating whether NH3 reductions were driven by TAN along with initial and final CPs showed a strong functional relationship between NH3 reductions and TAN at an adjusted R2 of 0.85 (RMSE = 7.41). TAN reductions were statistically significant in the model (p < 0.05).

A descriptive statistical analysis of the role of different manure stages on NH3 emission reductions from reduced CP in cattle indicates differences in estimates. Estimates showed reductions of 14 ± 6% (n: 7, Max: 22%, Min: 4%) for housing, 19 ± 5% (n: 11, Max: 13%, Min: 1%) for storage and 7 ± 7% (n: 2, Max: 13%, Min: 0%) for application when averaged over a %-point reduction in CP. However, similar to the case in pigs, these differences between measurement stages were not statistically significant when tested using an ANCOVA method.

Differences in NH3 emissions between pigs and cattle following reduced CP in diets

The differences between cattle and pigs with respect to NH3 emission reductions were compared using an ANCOVA method. The best fitted models that explained NH3 emission reductions for both pig and cattle, Model 1 [p] and Model 1 [c] were tested against each other. This involved the addition of a class effect for species as a main effect, as well as the interactions between regression factors.

Testing the difference between cattle and pigs using Model 1 [p] indicates an influence of CP reduction, final CP and the interaction between initial and final CP for both cattle and pigs. All the factors included in the model along with the interaction between CP reduction and species type were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The empirical equations, Model 1 [pm = pig model, p = pig] and Model 1 [pm, c = cattle] along with the parameter estimates are reported below.

Figure 3 illustrates the difference between cattle and pigs when tested against each other at varying levels of CP reductions and final CP. Similar to the case in pigs (Model 1 [p]), the figure shows that greater NH3 emission reductions are obtained with high CP reduction and low final CP for both animal types. The difference between cattle and pigs are significant for all levels of final CP when CP reductions are greater than 3.5%. However, as the final CP level increases, the difference between cattle and pigs are significant even at lower CP reductions. The slopes of the graphs between pigs and cattle shows that even at low CP levels, the NH3 reductions for a particular CP reduction is higher for cattle than pigs. For example, at a final CP level of 12%, a CP reduction of about 5%-points in cattle diets could reduce NH3 emissions by 80%. However, in the case of pigs, to achieve the same NH3 reductions at a final CP level of 12%, the CP reductions would have to be in the order of 9%-points. This is also reflected in the parameter estimates of the slopes for both cattle and pigs. Slopes for CP reduction shows that a reduction in CP is 31% more effective in reducing NH3 emissions for cattle as compared to pigs. Even when it comes to slopes of final CP, cattle were 60% more effective in reducing NH3 emissions relative to pigs.

Examining the difference between cattle and pigs using Model 1 [c] reveals an influence of CP reduction on both animal types (p < 0.05). The interaction between species type and CP reduction was also significant (p < 0.05). The empirical equations, Model 1 [cm = cattle model, p = pig] and Model 1 [cm, c = cattle] along with the parameter estimates are reported below.

Figure 4 illustrates the difference between cattle and pigs when tested against each other at varying levels of CP reductions. Similar to the case in cattle (Model 1 [c]), the figure shows that greater NH3 emission reductions are achieved with high CP reduction for both animal types. The difference between cattle and pigs are significant when CP reductions are greater than 2.5%. The slopes in Fig. 4 show that cattle are more sensitive to CP reductions and have higher NH3 reductions than pigs for a similar CP reduction. The parameter estimates for the slopes indicate that cattle were 53% more effective in reducing NH3 emissions as compared to pigs.

Discussion

Implication of reduced CP on NH3 emissions in cattle and pigs

The results presented confirm the expectation that there is potential to reduce NH3 emissions by lowering CP in animal diets. Overall averages of emission estimates considered in this study report NH3 reductions of 17 ± 6% per %-point CP for cattle relative to 11 ± 6% for pigs. The higher reductions in NH3 emissions for cattle relative to pigs were also statistically significant when tested against each other. Since the NH3 emission reductions calculated in this study were based on measured emission reductions from published literature, a direct comparison of emission estimates and relationships with those from experimental studies was not possible. Additionally, studies that have reviewed the emission reductions from reduced CP in animal diets distinguishing between cattle and pigs are rare. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe’s (UNECE) document on NH3 abatement reports NH3 reductions in the range of 5–15% for each %-point reduction in CP content in animal diets (Oenema et al. 2014). The relationships between CP traits, TAN and NH3 emissions were better correlated in cattle as compared to pigs. In the case of pigs, NH3 reductions were dependent on CP reductions and the level of final CP (R2 = 0.53, see Fig. 1). Cattle on the other hand showed a strong correlation between CP reductions and NH3 emissions (R2 = 0.80, see Fig. 2). The results from an experimental study by Swensson (2003) also indicated a strong relationship between CP reductions and NH3 emissions for cattle (R2 = 0.91).

An evaluation of factors such as the manure management stage at which NH3 is measured and pig categories (gilts, barrows and boars) showed differences in mean NH3 emission reduction estimates. However, a statistical analysis of the effect of the manure management stage at which NH3 emissions were measured did not reveal a significant influence on NH3 emission reductions for either cattle or pigs. As far as pig categories are concerned, five studies among the 14 used for the meta-analysis measured the impacts of reduced CP in boars. Boars have a higher protein accretion potential than gilts or barrows (Campbell and King 1982; Campbell and Dunkin 1983; Campbell et al. 1985). Even at a higher CP diet, boars retain a bulk of the protein instead of excreting it. Hence, the effect of a CP reduction in boar diets might not be as pronounced in reducing NH3 emissions as compared to gilts or barrows. Even though a comparison of the mean emission reduction estimates between boars and gilts/barrows revealed such a relationship, a statistical analysis of the differences was insignificant. A similar analysis could not be performed for cattle since the studies analysed were limited mostly to dairy cattle.

One of the main findings of this study is the higher NH3 emission reductions with reduced CP along with a clearer trend in relationships between CP, NH3 and TAN for cattle as compared to pigs. This could be attributed to the specific physiology of ruminants such as cattle, to efficiently recycle nitrogen in situations of low protein intake (Van Soest 1994), leading to a greater cut-down on CP. Additionally, due to the greater attention given to feed optimization in pigs relative to cattle, pig diets used in this study might have already been well balanced as opposed to cattle diets. This imbalance in cattle diets could have then amplified the effect of reducing CP on NH3 emissions. However the implications of nutrient balance on NH3 emissions could not be studied in detail here, since the nutrient requirement of animals depend on many factors including genetic background of animals, traits of main (economic) interest and price of nutrients, among others. Tables S.1 and S.2 reports the sources, feed composition and initial and final CP levels of studies included in the meta-analysis which could be used to investigate the relationship between protein balance and its influence on NH3 emissions.

Despite the higher reductions of NH3 as pointed out in this study, cattle have received relatively less attention than pigs in terms of implementing specific feeding strategies as a means for reducing NH3. This is probably due to the following reasons: Pig production systems are standardized based on conceptual logics of industrial production, whereas cattle production systems are much more heterogeneous (Raney et al. 2009), which is paralleled by restricted possibilities for practical process control. Due to the standardisation of pig production systems over the last five decades, pig production was gradually disconnected from the land area utilized for feed production which allowed for a concentration of large herds on relatively small areas of land (Marquer 2010; Thornton 2010), where the environmental impact became more obvious. In addition, due to the function of the symbiotic rumen microbiota, ruminants like cattle are less dependent on highly digestible, protein-rich feeds which are typical in pig production systems. Hence dietary manipulation concepts such as reduced CP and external amino acid supplementation have been implemented in pig production relatively early, in order to, among other advantages, abate NH3 emissions. With the growing demand for milk and meat dictating a higher production efficiency and performance in cattle, the capacity of rumen symbionts might not be enough to meet the animal requirements. In this case, cattle diets may also be supplemented with certain external protein and amino acid supplements, which are likely to influence NH3 emissions (Robinson 2010). There is also the risk of an oversupply of protein in traditional production systems, where cattle feed on physiologically young grass, which is rich in protein, particularly in spring and autumn (Van Soest 1994). Hence, in various production systems, CP in cattle diets might be (temporarily) in excess of the animal requirements. The larger NH3 abatement and the more direct relationship of CP with NH3 and TAN in the case of cattle highlight an opportunity to further reduce NH3 emissions from livestock manure.

Additional factors influencing NH3 emission reductions

The wealth of information collected from literature in this study allowed to further discern effects on NH3 emissions beyond those tangible by statistical analysis. A statistical evaluation of these factors was not possible due to limited data availability However, a discussion of these factors is important in the prospective design of emission measurement studies and also to fully assess NH3 emission abatement from reduced CP in animal diets.

Manure management systems

Variability in emission reductions could arise from the differences between manure management systems. Studies have shown that the type of housing, storage and application methods associated with different manure management systems influence emissions of NH3 (Amon et al. 2001; Külling et al. 2001; Webb et al. 2010). For example, a study by Külling et al. (2001) measured the effect of reduced CP on NH3 emissions for various storage types ranging from slurry, urine rich slurry, farmyard manure and deep litter. The NH3 emission reductions showed substantial variation in the range of 9–30% per %-point reduction in CP, highlighting the variability associated with different storage types on NH3 emission patterns. A detailed investigation separating the effect of manure management systems on NH3 emissions is beyond the scope of this analysis. However, proper categorization and consideration of differences between manure management systems during measurement and quantification of emission reductions could help reduce variability in emission estimates.

Nutritional factors

The studies used in this analysis were all checked for fulfilment of the animals’ nutritional requirements. One of the studies excluded from the analysis involved unrealistic CP levels in pig diets. The levels of CP fed were around 6%, which may be useful for metabolic or physiological studies, but lack practical relevance. Also, the level of external amino acid supplements was on the lower side, which resulted in a supply of essential amino acids around 25% below the requirement during the growing stage (Otto et al. 2003).

The type of CP fed also influences the N flow in manure and subsequent NH3 emissions. In terms of pigs, most studies used soybean products as a source of CP. However, in the case of cattle, both soybean and urea were used as a source of protein and non-protein nitrogen, respectively. Urea is immediately degradable in the rumen, while true proteins like soybean take some time to degrade (Van Soest 1994). Analysing the rumen degradability of protein sources might be a way to address comparability issues between studies with ruminants that involve similar CP reductions, but include different protein sources.

Physiological stage

The physiological stage of animals could also influence the excretion rate and NH3 emissions. In the early growing stage the N retention is low as compared to the finishing phase. In physiological stages where the N retention rate and hence the protein and amino acid requirement of the animal is low, a reduction of CP that is beyond requirement will have a large impact on reduction of NH3 emissions. Hernández et al. (2013) showed that the NH3 emission reductions from growing pigs were higher than the finishing phase, when subject to the same level of CP reduction. Montalvo et al. (2013) measured reductions in NH3 from decreasing CP in piglets. The authors found NH3 reductions near 20% per %-point of CP. Although this looks promising, the practical implication needs to be questioned, since piglets consume relatively small amounts of feed over a limited period of time and hence the potential of cutting down CP in their diets to reduce NH3 emissions is rather low. In the case of cattle, a similar comparison could not be made since NH3 emission reduction experiments for growing cattle subject to reduced CP were not available in the dataset. Accounting for metrics such as N retention levels could help in further analysing results from studies that involve different physiological stages of animals.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis confirms that CP in animal diets and emissions of NH3 show a clear relationship. The meta-analysis revealed mean NH3 reduction of 17 ± 6% per %-point CP for cattle and 11 ± 6% for pigs. Analysis of variability in NH3 emission reductions due to emissions measured at different manure management stages and across pig categories showed trends, but not a significant influence. Statistical models showed that significant relationships exist between reduced CP, TAN content in the manure and NH3 emissions for both animal types. Testing the difference between cattle and pigs indicates significant differences between both animal types with higher NH3 reductions for cattle as compared to pigs, following a reduction of CP in animal diets. This increased reduction along with a clearer trend in relationships between CP and NH3 emissions for cattle is very relevant in terms of agricultural policy, since in the past, efforts to reduce NH3 emissions via dietary manipulation were targeted primarily towards pigs. With increasing pressure on agriculture to tackle its nitrogen footprint, extending the concepts of feed optimization from pig and poultry diets to cattle can provide an additional pathway to further reduce NH3 emissions from livestock manure. This study improves the current knowledge by quantitatively analysing NH3 reduction potentials per %-point CP reduction and evaluating the relationships between CP traits, TAN content in the manure and NH3 reductions.

References

Agle M, Hristov A, Zaman S, Schneider C, Ndegwa P, Vaddella V (2010) The effects of ruminally degraded protein on rumen fermentation and ammonia losses from manure in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 93:1625–1637

Amon B, Amon T, Boxberger J, Alt C (2001) Emissions of NH3, N2O and CH4 from dairy cows housed in a farmyard manure tying stall (housing, manure storage, manure spreading). Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 60:103–113

Arriaga H, Salcedo G, Martínez-Suller L, Calsamiglia S, Merino P (2010) Effect of dietary crude protein modification on ammonia and nitrous oxide concentration on a tie-stall dairy barn floor. J Dairy Sci 93:3158–3165

Bittman S, Dedina M, Howard C, Oenema O, Sutton M (2014) Options for ammonia mitigation: guidance from the UNECE task force on reactive nitrogen. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Edinburgh. http://www.clrtap-tfrn.org/sites/clrtap-tfrn.org/files/documents/AGD_final_file.pdf. Accessed 24 Oct 2017

Campbell R, Dunkin A (1983) The influence of protein nutrition in early life on growth and development of the pig. Br J Nutr 50:605–617

Campbell R, King R (1982) The influence of dietary protein and level of feeding on the growth performance and carcass characteristics of entire and castrated male pigs. Anim Sci J 35:177–184

Campbell R, Taverner M, Curic D (1985) Effects of sex and energy intake between 48 and 90 kg live weight on protein deposition in growing pigs. Anim Sci J 40:497–503

Canh T, Aarnink A, Verstegen M, Schrama J (1998) Influence of dietary factors on the pH and ammonia emission of slurry from growing-finishing pigs. J Anim Sci 76:1123–1130

Chadwick D, Sommer S, Thorman R et al (2011) Manure management: implications for greenhouse gas emissions. Anim Feed Sci Technol 166:514–531

Crosson P, Shalloo L, O’Brien D, Lanigan G, Foley P, Boland T, Kenny D (2011) A review of whole farm systems models of greenhouse gas emissions from beef and dairy cattle production systems. Anim Feed Sci Technol 166:29–45

FAO (2011) Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Statistics Division, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/statistics/en/. Accessed 20 Oct 2016

Feilberg A, Sommer SG (2013) Ammonia and Malodorous Gases: Sources and Abatement Technologies. In: Sommer SG, Christensen ML, Schmidt T, Jensen LS (eds) Animal manure recycling: treatment and management. Wiley, Chichester, pp 153–175

Frank B, Swensson C (2002) Relationship between content of crude protein in rations for dairy cows and milk yield, concentration of urea in milk and ammonia emissions. J Dairy Sci 85:1829–1838

Gerber PJ, Steinfeld H, Henderson B et al (2013) Tackling climate change through livestock—a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3437e.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2016

Hansen CF, Sørensen G, Lyngbye M (2007) Reduced diet crude protein level, benzoic acid and inulin reduced ammonia, but failed to influence odour emission from finishing pigs. Livest Sci 109:228–231

Hayes E et al (2004) The influence of diet crude protein level on odour and ammonia emissions from finishing pig houses. Bioresour Technol 91:309–315

Hernández F et al (2013) Effect of dietary crude protein levels in a commercial range, on the nitrogen balance, ammonia emission and pollutant characteristics of slurry in fattening pigs. Animal 5(8):1290–1298

Hou Y, Velthof GL, Oenema O (2015) Mitigation of ammonia, nitrous oxide and methane emissions from manure management chains: a meta-analysis and integrated assessment. Glob Change Biol 21:1293–1312

Hou Y, Velthof GL, Lesschen JP, Staritsky IG, Oenema O (2017) Nutrient recovery and emissions of ammonia, nitrous oxide and methane from animal manure in Europe: effects of manure treatment technologies. Environ Sci Technol 51:375–383

James T, Meyer D, Esparza E, DePeters E, Perez-Monti H (1999) Effects of dietary nitrogen manipulation on ammonia volatilization from manure from Holstein heifers. J Dairy Sci 82:2430–2439

Kim D-G, Saggar S, Roudier P (2012) The effect of nitrification inhibitors on soil ammonia emissions in nitrogen managed soils: a meta-analysis. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 93:51–64

Kim D-G, Hernandez-Ramirez G, Giltrap D (2013) Linear and nonlinear dependency of direct nitrous oxide emissions on fertilizer nitrogen input: a meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 168:53–65

Koenig K, McGinn S, Beauchemin K (2013) Ammonia emissions and performance of backgrounding and finishing beef feedlot cattle fed barley-based diets varying in dietary crude protein concentration and rumen degradability. J Anim Sci 91:2278–2294

Külling D, Menzi H, Kröber T, Neftel A, Sutter F, Lischer P, Kreuzer M (2001) Emissions of ammonia, nitrous oxide and methane from different types of dairy manure during storage as affected by dietary protein content. J Agric Sci 137:235–250

Le P, Aarnink A, Jongbloed A, Van der Peet-Schwering C, Ogink N, Verstegen M (2008) Interactive effects of dietary crude protein and fermentable carbohydrate levels on odour from pig manure. Livest Sci 114:48–61

Le P, Aarnink A, Jongbloed A (2009) Odour and ammonia emission from pig manure as affected by dietary crude protein level. Livest Sci 121:267–274

Lee C, Hristov A, Dell C, Feyereisen G, Kaye J, Beegle D (2012) Effect of dietary protein concentration on ammonia and greenhouse gas emitting potential of dairy manure. J Dairy Sci 95:1930–1941

Leek A, Callan J, Henry R, O’Doherty J (2005) The application of low crude protein wheat-soyabean diets to growing and finishing pigs: 2. The effects on nutrient digestibility, nitrogen excretion, faecal volatile fatty acid concentration and ammonia emission from boars. Ir J Agric Food Res 44:247–260

Leek A, Hayes E, Curran TP, Callan J, Beattie V, Dodd VA, O’Doherty JV (2007) The influence of manure composition on emissions of odour and ammonia from finishing pigs fed different concentrations of dietary crude protein. Bioresour Technol 98:3431–3439

Loyon L, Burton C, Misselbrook T, Webb J et al (2016) Best available technology for European livestock farms: availability, effectiveness and uptake. J Environ Manage 166:1–11

Lynch M, Sweeney T, Callan J, Flynn B, O’Doherty J (2007) The effect of high and low dietary crude protein and inulin supplementation on nutrient digestibility, nitrogen excretion, intestinal microflora and manure ammonia emissions from finisher pigs. Animal 1(8):1112–1121

Lynch M, O’Shea C, Sweeney T, Callan J, O’Doherty J (2008) Effect of crude protein concentration and sugar-beet pulp on nutrient digestibility, nitrogen excretion, intestinal fermentation and manure ammonia and odour emissions from finisher pigs. Animal 2(3):425–434

Madrid J, Martínez S, López C, Orengo J, López M, Hernández F (2013) Effects of low protein diets on growth performance, carcass traits and ammonia emission of barrows and gilts. Anim Prod Sci 53:146–153

Malek E, Davis T, Martin RS, Silva PJ (2006) Meteorological and environmental aspects of one of the worst national air pollution episodes (January, 2004) in Logan, Cache Valley, Utah, USA. Atmos Res 79:108–122

Marquer P (2010) Pig farming in the EU, a changing section. Eurostat, Statistics in Focus 8/2010. European Commission. Agriculture and Fisheries. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3433488/5564612/KS-SF-10-008-EN.PDF/d7615da8-004d-4d44-b04b-6106bea1772e?version=1.0. Accessed on Apr 2017

Misselbrook T, Powell JM, Broderick G, Grabber J (2005) Dietary manipulation in dairy cattle: laboratory experiments to assess the influence on ammonia emissions. J Dairy Sci 88:1765–1777

Montalvo G, Morales J, Pineiro C, Godbout S, Bigeriego M (2013) Effect of different dietary strategies on gas emissions and growth performance in post-weaned piglets. Span J Agric Res 11:1016–1027

O’Connell J, Callan J, O’Doherty J (2006) The effect of dietary crude protein level, cereal type and exogenous enzyme supplementation on nutrient digestibility, nitrogen excretion, faecal volatile fatty acid concentration and ammonia emissions from pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol 127:73–88

O’Shea C, Lynch B, Lynch M, Callan J, O’Doherty J (2009) Ammonia emissions and dry matter of separated pig manure fractions as affected by crude protein concentration and sugar beet pulp inclusion of finishing pig diets. Agric Ecosyst Environ 131:154–160

Oenema O, Tamminga S, Menzi H, Aarnik A, Pineiro C (2014) Livestock feeding strategies. In: Bittman S et al (eds) Options for ammonia mitigation: guidance from the UNECE task force on reactive nitrogen, convention on long range transboundary air pollution. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Edinburgh, pp 10–13. http://www.clrtap-tfrn.org/sites/clrtap-tfrn.org/files/documents/AGD_final_file.pdf. Accessed on 24 Oct 2017

Otto E, Yokoyama M, Hengemuehle S, Von Bermuth R et al (2003) Ammonia, volatile fatty acids, phenolics, and odor offensiveness in manure from growing pigs fed diets reduced in protein concentration. J Anim Sci 81:1754–1763

Panetta D, Powers WJ, Xin H, Kerr BJ, Stalder KJ (2006) Nitrogen excretion and ammonia emissions from pigs fed modified diets. J Environ Qual 35:1297–1308

Patra AK (2013) The effect of dietary fats on methane emissions, and its other effects on digestibility, rumen fermentation and lactation performance in cattle: a meta-analysis. Livest Sci 155:244–254

Portejoie S, Dourmad J, Martinez J, Lebreton Y (2004) Effect of lowering dietary crude protein on nitrogen excretion, manure composition and ammonia emission from fattening pigs. Livest Prod Sci 91:45–55

Raney T et al (2009) The state of food and agriculture: livestock in the balance. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0680e/i0680e.pdf

Robinson PH (2010) Impacts of manipulating ration metabolizable lysine and methionine levels on the performance of lactating dairy cows: a systematic review of the literature. Livest Sci 127:115–126

Rosenthal R (1985) Writing meta-analytic reviews. Psychol Bull 118:183

Sauvant D, Schmidely P, Daudin J-J, St-Pierre NR (2008) Meta-analyses of experimental data in animal nutrition. Animal 2:1203–1214

Stewart A, Little S, Ominski K, Wittenberg K, Janzen H (2009) Evaluating greenhouse gas mitigation practices in livestock systems: an illustration of a whole-farm approach. J Agric Sci 147:367–382

Sutton MA, Howard CM, Erisman JW, Billen G, Bleeker A, Grennfelt P, Van Grinsven H, Grizzetti B (2011) The European nitrogen assessment: sources, effects and policy perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 9–32

Swensson C (2003) Relationship between content of crude protein in rations for dairy cows, N in urine and ammonia release. Livest Prod Sci 84(2):125–133

Thornton PK (2010) Livestock production: recent trends, future prospects. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365:2853–2867

UNECE (2015) Methane and ammonia air pollution. Policy brief prepared by the UNECE task force on reactive nitrogen. Task force on reactive nitrogen, Working Group on Strategies and Review of the UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, Aarhus. http://www.clrtap-tfrn.org/content/methane-and-ammonia-air-pollution. Accessed on 24 Oct 2017

UNECE (2016) Convention of long-range transboundary atmopsheric pollution. United Nations Economic Communication for Europe, Geneva. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/environment/air-emissions-inventories/database. Accessed on 16 Nov 2016

Van Soest PJ (1994) Nutritional ecology of the ruminant. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

van Vuuren AM et al (2015) Economics of low nitrogen feeding strategies. Costs of ammonia abatement and the climate co-benefits. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 35–51

Wang Y, Dong H, Zhu Z et al (2017) Mitigating greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from swine manure management: a system analysis. Environ Sci Technol 51(8):4503–4511

Webb J, Pain B, Bittman S, Morgan J (2010) The impacts of manure application methods on emissions of ammonia, nitrous oxide and on crop response—a review. Agric Ecosyst Environ 137:39–46

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF). This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under research Grant W 1256-G15 (Doctoral Programme Climate Change—Uncertainties, Thresholds and Coping Strategies).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sajeev, E.P.M., Amon, B., Ammon, C. et al. Evaluating the potential of dietary crude protein manipulation in reducing ammonia emissions from cattle and pig manure: A meta-analysis. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 110, 161–175 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-017-9893-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-017-9893-3