Abstract

Reinforced concrete as the most important construction material suffers from long-term deterioration due to different exposure conditions. Fire attack is a critical exposure condition as it can lead to complete collapse of the structure. On the other hand, the repair and strengthening of existing structures have become necessary both technically and financially. Moreover, since high-performance concretes (HPCs) are extensively used as repairing or strengthening materials for different structures, their performance after exposure to elevated temperature needs to be investigated. Therefore, this study is directed to investigate the post-fire flexural behavior of RC slabs cast with traditional normal strength concrete (NSC) and strengthened with HPC. Twenty-one RC slabs were prepared and tested including casting the full thickness with the same mixture (single-concrete slabs) and composite slabs (cast with NSC and HPC). Different variables were considered; using high strength concrete, 30% fly ash, 30% slag, 0.5% polypropylene, 0.5% steel fibers, hybrid fibers (0.5% steel + 0.5% polypropylene), reinforcement ratio, the side exposed to elevated temperature (tension or compression), and joining the HPC layer to the NSC (shear studs or epoxy resin). The slabs were exposed to the required temperature of 600°C for 2 h. The results show that strengthening the RC slab in tension or compression by using HPC remarkably enhanced the slab’s performance after exposure to elevated temperature. Specially, composite slabs containing hybrid fibers in tension side when exposed to elevated temperature from the tension side recorded the highest cracking load, ultimate load, stiffness, toughness, and ductility index as compared to the NSC slab, with increases of 92.8%, 116%, 157%, 335%, and 86.9%, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

During its lifetime, reinforced concrete structures may face several severe exposure conditions which may threaten its safety. Moreover, exposure to fire or elevated temperature is being one of such conditions that may lead to structure collapse [1]. The elevated temperature leads to a change in the chemical and physical composition of concrete, resulting in deterioration of the mechanical properties of concrete and concrete cracking [2]. Furthermore, the temperature causes degradation of the yielding strength of reinforcement, which consequently increases the deformation of the member, which may result in undesirable structural failures [3, 4].

Under the pressure of population booms and land limitations, to effectively resolve housing and transportation issues, the need for high-rise buildings and underground construction is rapidly increasing. This leads to the development of a new type of concrete called high-performance concrete (HPC) with enhanced properties through the use of pozzolanas, admixtures, and fiber. These HPC mixes include ultra-high strength concrete, high strength concrete (HSC), fly ash concrete (FAC), blast furnace slag concrete (BFSC), and fiber-reinforced concrete [5]. The use of HPC allows for a higher load carrying capacity of members at a lower cost [6] by decreasing the member dimensions, which consequently increases usable space and decreases the unit weight for a given strength. The application of HPC is widely spreading around the world in tall buildings, tunnels, and highway bridges [7, 8]. Also, HPC provides its efficiency as a strengthening material for structure members [9,10,11,12]. Haddad et al. [10] concluded that the one-way RC slab heated at 600°C for 2 h and repaired by using a high strength steel fiber concrete layer regained about 79% to 84% of the original load capacity with a corresponding increase in stiffness in the range of 380% to 500%.

The rapid increase of HPC as a replacement for traditional normal strength concrete (NSC) led the researchers to focus on identifying its behavior when it is subjected to fire. Several studies have been performed to investigate the fire performance of RC members [13,14,15,16,17,18]. It was observed that the fire behavior of RC members depended on concrete strength, material properties, structural boundary conditions, surface area exposed to fire, cooling type, in addition to fire conditions. HSC showed more deterioration with a higher rate in its mechanical properties than NSC under fire [19], where the dense microstructure of HSC accelerated the pore pressure development leading to spalling [20, 21]. This spalling has an adverse effect on reducing the concrete sections, and increasing the temperature in reinforcement bar and consequently reduces the strength and stiffness of RC concrete members [14, 22]. On the other hand, Shariq et al. [23] studied the flexural behavior of RC beams cast with HSC and NSC after exposure to different temperatures up to 800°C for 3 h and concluded that the ultimate load of RC beams cast with HSC increased by 15%, 20%, 70%, and 85% as compared to those cast with NSC after exposure to different temperatures of 200°C, 400°C, 600°C, and 800°C, respectively.

In order to improve the fire performance of RC members, researchers have suggested a number of solutions, such as adding fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag, and fiber to the concrete mix, as depicted in Table 1. The researchers concluded that using fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag can improve the mechanical properties of concrete at high temperatures and enhance its fire resistance [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Ghazy et al. [29] reported that HPC containing ground granulated blast furnace slag combined with steel fiber (SF) has an evident effect on the residual tensile and flexural strengths of HPC after exposure to a temperature of 800°C, where the retained residual tensile and flexural strengths were 63.7% and 55%, respectively.

Regarding the use of fibers, several researchers studied the effect of adding SF, polypropylene fiber (PPF), and hybrid fibers on the mechanical properties of concrete at high temperatures. The results revealed that the mechanical properties of concrete at high temperatures were improved by adding fibers [5, 30,31,32,33]. Ghazy et al. [18] investigated the mid-span deflection of full-scale slab cast with NSC, HSC, FAC, HPC-SF, and HPC-PPF under the combined effect of load and fire. It was found that HPC-PPF had the optimal structural behavior in terms of lower deflection and lower reinforcement temperature, while NSC recorded the highest mid-span deflection. Further, Du and Zhang [34] reported that the rebar mesh and PP fibers reduce the occurrence of spalling of RC slabs under fire since the fibers melt at approximately 160–170°C and produce additional porosity in concrete, which facilitates the dissipation of temperature-induced vapor pressure. In case of steel fiber, the improvement in the tensile strength of concrete at elevated temperature is the main factor that prevents spalling of concrete [20]. Shariq et al. [23] concluded that the addition of 0.5% SF to RC beam can yield ductile failure and delay the initiation of flexural and shear cracks at different temperatures up to 800°C. Moreover, Jafarzadeh and Nematzadeh [35] reported that SF significantly improved the load carrying capacity and reduced the mid-span deflection of the beam after being exposed to high temperature up to 600°C. Besides, the addition of SF can improve the bond strength between reinforcement bars and concrete after exposure to high temperatures [36]. On the other hand, a few studies showed that adding SF led to more explosive spalling of structural members due to SF bridges cracking and preventing steam from escaping [21, 37, 38]. Monte et al. [38] concluded that the slabs cast with concrete mixes made of HPC and HPC containing SF showed explosive spalling, while adding PPF can prevent spalling. The spalling is due to the influence of steel fibers in limiting the crack widths and preventing the dissipation of water vapor generated in concrete, leading to the buildup of high pore pressure. The concrete spalling depends on heating rate, specimen geometry, moisture content, boundary conditions, type of test, and experimental conditions.

The performance of the strengthened structures strongly depended on the interaction of the two concrete layers, where the shear forces may cause sliding failure along the interface between the two concrete layers. The load transfer capacity of the interface depended on the interface shear strength, which was significantly influenced by interface preparation (roughness and cleanliness) and reinforcement crossing the interface [39]. Fernandes et al. [40] showed that the debonding load of RC slab strengthened with reinforced concrete overlay on the tensile face in the case of a shear stud increased by three times than reference specimens without shear stud.

In the fire case, Xu et al. [41] conducted an experimental study to investigate the fire resistance performance of two-way restrained precast concrete composite slabs. The study found that the shear stud at the interface between the precast and the in-situ concrete layers is sufficient to ensure composite action in fire. Ahmad et al. [42] presented an experimental investigation on the shear transfer strength of uncracked concrete interfaces after exposure to different temperatures. It was shown that the elevated temperature resulted in a reduction of the shear transfer strength by 48.17% after exposure to a temperature of 750°C. While specimens without transverse reinforcement displayed the maximum loss in shear transfer strength, the increase in transverse reinforcement ratio led to a decrease in the loss in shear transfer strength. Moreover, Xiao et al. [43] observed that the concrete with higher compressive strength showed more deterioration in shear transfer strength. On the other hand, epoxy resin has a negative effect under fire because it reaches the glass transition temperature (Tg). The glass transition temperature is the temperature at which the polymer goes from a hard, glass-like state to a rubber-like state, as mentioned by Blontrock et al. [44].

The above review mentioned that numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the fire performance of HSC members. However, a few studies have explored the influence of fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag with fiber on the fire performance of RC members. Thus, the aim of this investigation is to study the fire performance of single-concrete and composite slabs cast with different HPC. This study will help engineers understand the in-situ behavior of the RC member strengthened with HPC when exposed to elevated temperatures and consider such performance when designing and implementing such materials in such situations to ensure their safety. Furthermore, the generated data on the fire behavior of RC slab strengthened with HPC layer will help validate finite element models to track the flexural behavior of RC slab strengthened with HPC under fire.

2 Experimental Work

The experimental program of the present study was designed to investigate the flexural behavior of composite RC slab cast with normal strength concrete (NSC) and strengthened with a layer of high-performance concrete (HPC) after exposure to elevated temperature compared to single RC slabs. Various parameters were taken into consideration when preparing and testing specimens including HPC types mainly; high strength concrete (HSC), (replacement 30% of cement by fly ash or ground granulated blast furnace slag), 0.5% steel fiber (SF) or polypropylene fiber (PPF) and hybrid fibers (0.5% SF + 0.5% PPF), strengthening side (tension or compression), the fire exposure side (tension or compression sides), reinforcement ratio (0 and 0.6%), and bonding the HPC layer to the NSC (using shear studs or epoxy resin).

2.1 Materials

Materials utilized in this experimental work were obtained from local Egyptian sources. The cement used to produce NSC and HPC was Portland cement (CEM I 42.5 N) complying with EN 196-1 [45] and ES 4756 [46]. The physical and mechanical properties of the used cement are presented in Table 2. Portland cement was replaced by either fly ash (FA) Class F or ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS). The physical properties and chemical analysis of the utilized FA and GGBFS are illustrated in Table 2. Crushed limestone as coarse aggregates with a nominal maximum size of 12.5 mm and sand as fine aggregates were used. The bulk specific gravity, the unit weight, and the water absorption for the coarse and fine aggregates were (2.6, 1500 kg/m3, 1%) and (2.55, 1550 kg/m3, 1.5%), respectively, according to ASTM-C127-01 [47], ASTM C128-01 [48], and ASTM-C29 [49]. The fineness modulus of the coarse and fine aggregates was 5.53 and 2.5, respectively, according to ASTM-C136 [50]. High range water-reducing admixtures (Polycarboxylate Ether) with 44% solid particles, which confirm ASTM-C494 type F&G [51] was utilized to prepare the concrete mixes.

Two types of fibers were incorporated, namely: hooked end steel fibers (SF) and polypropylene fibers (PPF). The mechanical and geometrical properties of these fibers as given by the manufacturer are presented in Table 3. Mild steel rebar with a 6 mm diameter was used as steel reinforcement and shear connector for the RC slabs and its properties is given in Table 3.

2.2 Mixtures Proportions, Specimens Preparation and Curing

Eight different concrete mixtures were prepared applying the absolute volume design method. The concrete mixture proportions are shown in Table 4. In preparing HPC, different parameters were considered including: (1) HSC (target strength of 65 MPa); (2) Using supplementary cementitious materials (30% FA or 30% GGBFS) replacement by cement weight based on [5, 24, 25, 27, 52]; (3) Incorporating 0.5% different types of fibers (0.5% SF, 0.5% PPF or hybrid fibers (0.5% SF + 0.5% PPF)) according to [33,34,35, 52].

A drum mixer with a capacity of 0.1 m3 was used for mixing the concrete mixtures. Firstly, the wooden forms were oiled and the steel reinforcements were placed inside. Thermocouples were fixed in the required positions. Firstly, cement or (cement + (FA or GGBFS) if applicable) were mixed for 1 min to ensure the uniformity of the constituents. The water, in addition to admixture, was added and the mixing continued for 1 min. Coarse aggregate was simultaneously charged into the mixer and mixed for another minute and then sand was added and mixed at least for 2 min. Finally, fibers were slowly added (if applicable) to the wet concrete, and the mixing process was continued for 2 min to assure the uniformity of the mixture.

The slump test was conducted for measuring and controlling the plastic fresh concrete consistency for different concrete mixes and keeping the slump values between 50 mm and 100 mm.

2.2.1 For Single RC Slabs

After mixing, the concrete mix was cast into forms and compacted using a vibrating table for 10 s. After 24 h, the slabs were demolded and cured for 28 days by covering the slab specimens with wet burlap, and then the slabs were placed at room temperature of 25°C with a relative humidity of 55% until the day of exposure to fire at 60 days of age.

2.2.2 For Composite RC Slabs

The first layer in the tension side was cast (half of the slab thickness (with 40 mm)) and compacted using a vibrating table for 10 s, then cured for 28 days by covering the slab specimens with wet burlap. After that, the half slab was placed in wooden forms and the remaining layer (40 mm) was cast. After 24 h, the slabs were demolded and cured for another 28 days by covering the slab specimens with wet burlap at room temperature of 25°C with a relative humidity of 55% until the day of exposure to elevated temperatures at 60 days age.

Furthermore, cube specimens with dimensions 100 × 100 × 100 mm, cylinders with 100 mm diameter and 200 mm height, and beams 100 × 100 × 500 mm were cast with concrete mixes to determine the mechanical properties (compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths), respectively, at 28 days and 60 days. The compression test was carried out at 28 and 60 days according to BS EN 12390-3 [53] while the splitting tensile and flexure tests were carried out at 60 days according to BS EN 12390–6 [54] and BS EN 12390-5 [55], respectively.

2.3 Slab Specimens Details

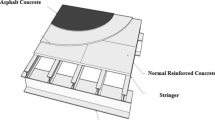

A total of 21 one-way RC slabs were designed and constructed according to the ACI 318 code [56]. The geometry and steel reinforcement of all slabs were the same, and the details of the slab specimens are shown in Figure 1. The slabs dimensions were 280 × 680 × 80 mm (width, length and thickness), respectively. The main and secondary reinforcements of 6 mm diameter were placed at a spacing of 62.5 mm and 108 mm, respectively.

One RC slab specimen was cast with NSC to represent a slab specimen at ambient temperature (N25). The other 20 slabs were subjected to an elevated temperature of 600°C for 2 h. Firstly, to study the behavior of RC single slabs, eight RC slabs for which the whole thickness was cast with the same concrete mixture. Secondly, to study the behavior of RC composite slabs, 12 composite RC slabs were cast with two layers. More factors were considered during preparation and testing of specimens; concrete types (HSC, FAC, GGBS), using 0.5% PPF or SF or hybrid (SF + PPF), joining the HPC layer to NSC (using epoxy resin or shear studs 5R 6 mm/130 mm as shown in Figure 1b), strengthening side (tension or compression), reinforcement ratio (0 and 0.6%), and elevated temperature exposure side (tension or compression sides). Table 5 presents the proposed program for RC slab specimens.

2.4 Heating of RC Slab

Figure 2 depicts the RC slab under fire test. The heating was performed in an electric furnace with opening dimensions of 750 mm × 650 mm and 800 mm in depth, as shown in Figure 2a. The composite slabs were exposed to a uniform temperature of 600°C at 60 days of age from one side, as shown in Figure 2b, where the exposure to elevated temperature was from either the tension side or the compression side. When the electrical furnace has reached the required temperature of 600°C, the furnace temperature is held for another 2 h, as shown in Figure 2c. At the end of the heating period, the electrical furnace was switched off and the slabs were left in the furnace to allow natural air cooling (gradual cooling) of room temperature at (25°C and 55% RH) for 24 h.

To measure the temperature distribution during the elevated temperature exposure, four thermocouples of type K (Chromel–Alumel) were used with a thickness of 0.91 mm. The thermocouples were placed in the RC slab at the exposed surface, reinforcement bar, mid slab thickness (interface between the two concrete layers), and unexposed surface (named TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4), respectively, as shown in Figure 3. The temperatures of the furnace and specimens were recorded through a data logger.

2.5 Slab Specimens Test Method

The slab specimens were tested under a four-point bending load test with a clear span of 600 mm, as illustrated in Figure 4. The load was applied using a Universal Testing Machine with Digital data acquisition system (300 kN total capacity) with an accuracy of 0.001 kN. A loading rate of 0.5 mm/min was applied to easily mark the observed cracks, as mentioned by Basha et al. [12]. A rigid steel beam was used to distribute the load through two-line loads. The displacement was measured by using LVDTs of 100 mm length with an accuracy of 0.01 mm at the mid-span of the slab.

3 Test Results and Discussion

3.1 Thermal Behavior

The elevated temperature behavior of one-way RC slabs in terms of temperature measurement across the RC slab thickness is illustrated in this section. The thermal behavior of slab specimens N and FP-N during heating and cooling phases by comparing the temperatures at different locations of 15 mm, 40 mm, and 80 mm (TC2, TC3, TC4), respectively, is presented in Figure 5. From this figure, it can be indicated that the temperature trends are similar for the tested RC slab samples, and the rate of temperature rise is small up to 100°C, after which the temperature increases rapidly with time. This is due to the energy consumption of evaporating water [34, 57]. Also, the temperature of the inner part of the slab (TC3 and TC4) is lower than the temperature recorded at the steel reinforcement location (TC2). Because of the low thermal conductivity and high specific heat of concrete, which delays the rise in temperature in the inner layers of concrete [25].

Figure 6 represents the temperature distribution of composite slabs. From this figure, it can be noticed that using a layer of FAC or BFSC (slab specimen F-N or G-N) can reduce the temperature at different thicknesses by approximately 50°C compared to slab specimen using a layer of HSC (slab specimen H-N), as depicted in Figure 6a. This is due to the use of FA or GGBFS (concrete mix FAC or GGBFC), which resulted in lower thermal conductivity of these concretes compared to HSC, and this is in agreement with the results of Khaliq and Kodur [5].

Moreover, the use of different types of fibers plays an important role in the temperature distribution of composite slabs. Where composite slab FP-N cast with FAC and PPF observed higher variation between rebar (T2) and inner parts (T3 and T4) in comparison to composite slab FS-N and FSP-N, which cast with steel or hybrid fibers (mixtures FAC-SF and FAC-(S+P)), respectively, as see in Figure 6b. This temperature difference is due to the fact that the use of PPF, which melts at 160°C and produces more voids, and decreases thermal conductivity [20, 21]. While the higher recorded temperatures in composite slabs FS-N and FAC-(S+P) are attributed to the contribution from the higher thermal conductivity of steel fibers [5].

3.2 Structural Behavior of RC Slab Specimens After Exposure to Elevated Temperature

Four-point loading test was conducted on RC slab with a clear span of 600 mm. The structural output results from the test included cracking load (Pcr), ultimate load (Pu), mid span deflection, stiffness, toughness, and ductility index have been studied for different RC slabs as presented in Table 6 and plotted in Figures 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Where the ductility index is defined as the ratio between the deflections at failure load \(({\Delta }_{\text{f}})\) and deflection at yield \(({\Delta }_{\text{y}})\) Equation 1 [58].

Stiffness is defined according to [59] and can be calculated by Equation 2

where P75% is the load level at 75% of the peak load in kN and Δ75% is the corresponding mid-span deflection in mm, and toughness is the total area under the load–deflection curve until failure load.

3.2.1 Load–Deflection Behavior

3.2.1.1 Single-Concrete Slabs

The load–deflection behavior of single-concrete slabs cast with different concrete types after one cyclic heating–cooling scheme is depicted in Figure 7. It is evident from Figure 7 that after exposure to 600°C, the slab specimen N showed a decrease in cracking load, ultimate load, ductility, stiffness, and toughness by 31.11%, 54.52%, 17.53%, 26%, and 74%, respectively, compared with the control slab specimen N25 (unexposed to elevated temperature). This decrease is due to the loss in strength of concrete with increasing temperature [2], as well as the loss of bonding strength between the reinforcing rebar and concrete at high temperature [23].

Furthermore, the slab specimens F and G cast with mix FAC and BFSC, respectively, showed an improvement in the cracking and ultimate loads compared to slab specimens N and H, as shown in Figure 8 and Table 6. The slab specimens F and G give the same cracking load, which increased by 101.6% and 12.8% compared to slab specimens N and H, respectively, where the ultimate load increased by (101%, 13.8%) and (96%, 11%), respectively, for slab specimens F and G relative to slab specimens N and H. This increase is due to the rehydration of FA, GGBFS, and cement particles after the cooling scheme, and the production of calcium silicate hydrate gel (C-S-H) [60], which results in recovery of mechanical properties as shown in Table 4. The results agree with Khaliq and Kodur [25], who indicated that the structural behavior of FA concrete column is better than that of HSC column.

The use of different fiber types (SF, PPF, and hybrid (SF+PPF)) had a positive effect on the cracking and ultimate loads of single concrete slab specimens, as listed in Table 6. The increase in cracking load of slab specimens FS, FP, FSP, and GS is 109.7%, 117.7%, 101.6%, and 120.16%, while the increase in ultimate load is 92.2%, 103.7%, 106.3%, and 123.3% compared to slab specimen N. These results are consistent with findings from the literature [8, 23]. The increase in cracking and ultimate loads is attributed to the use of SF, which improves the mechanical properties of concrete at high temperatures (see Table 3) [4, 5, 20, 61, 62]. PPF melts at 160°C and produces new voids, which reduce the thermal conductivity of concrete and consequently, reduce the temperature of reinforcement [4, 21]. On the other hand, fibers had a marginal effect on the ultimate load compared to the same slab specimen without fibers as shown in Figure 8.

Moreover, the slab specimens cast with different types of HPC (H, F, G, FS, FP, FSP, and GS) showed a ductile manner coupled with a large mid-span deflection compared to slab specimen N. The maximum recorded mid span deflection ranged from 18.6 mm to 30 mm, compared to 15.89 mm for the slab specimen N with an increasing percentage of 17.1% to 88.8%. The increment in the mid span deflection may be due to the use of FA and GGBFS, which improve the concrete compressive strength at high temperatures [29] and increase the bond strength between reinforcement bar and concrete. Moreover, the incorporation of SF enhances the ductility of slabs under elevated temperatures, as reported by Ghazy et al. [18] and Ahmed et al. [62].

3.2.1.2 Composite Slabs

Figure 9 shows the load deflection curves for composite RC slabs. Figure 9a illustrates the effect of using different concrete types without fibers on the behavior of composite RC slabs after exposure to elevated temperature, where slab specimens H-N, F-N, and G-N were strengthened with HSC, FAC, and BFSC in tension, respectively. From Figure 9a, it can be noted that composite slabs H-N and F-N exhibited better performance than the single concrete slab specimen N. Cracking and ultimate loads are shown in Figure 8 and listed in Table 6. The slab specimen F-N yielded the highest cracking and ultimate loads with 77.4% and 61.3% higher than slab specimen N, while G-N showed a decrease in cracking and ultimate loads by 3.22% and 6.4%, respectively. The decrease in the cracking and ultimate loads of slab specimen G-N is due to the deference in the thermal expansion of the BFSC layer and NSC layer, which resulted in a crack on the interface between the two concrete layers and consequently reduced the shear transfer strength on the interface, as discussed by [42, 43]. On the other hand, slab specimen H-N recorded cracking and ultimate loads with significant increases of 21% and 33.6%, respectively, compared to slab specimen N.

Regarding the influence of different fiber types, Figure 9b depicts the load deflection relationships for composite slab specimens FS-N, FP-N, FSP-N, and GS-N. The results showed that all composite slabs recorded an increase in the mid-span deflection by 57% compared to slab specimen N (concrete mix without fibers). The results presented in Figure 8 and Table 6 show that using fibres significantly enhanced the cracking and ultimate load of the composite slab in comparison with slab specimen N. The percentages of increases in the cracking load relative to slab specimen N are (45.2%, 75%, 117.7%, and 27%) for slab specimens FS-N, FP-N, FSP-N, and GS-N, respectively, while the improvements in the ultimate load are (65.6%, 79.2%, 116.1%, and 22.5%). This increase is due to the chemical reaction of HPC constitutive, which fills the pores in the interface between the two concrete layers and produces a shear connector that is able to enhance the interface bond strength [63]. In addition, the strong bond between fibres and concrete for slabs FS-N, FSP-N, and GS-N, as observed by Shariq et al. [23]. Moreover, the use of SF minimizes the crack width and delays the crack propagation, in addition to its role in improving the bond between reinforcement bar and concrete, as discussed by Haddad et al. [36]. Besides, shear studs play a role in improving the bond between the two concrete layers and increasing the shear transfer strength at the interface [40, 41].

It should be noted that composite slab cast with fly ash concrete and using hybrid fibers tension side (slab FSP-N) had optimal behavior after exposure to elevated temperature. As depicted in Table 6, slab specimen FSP-N exhibits the highest cracking and ultimate loads and recoded 27 kN and 31.94 kN, respectively, with increased ratios of 117.7% and 116.1% compared to slab specimen N. Moreover, the cracking and ultimate loads for slab FSP-N exceed those of single slab FSP by 8% and 4.76%, respectively. This proved the strong bonding between the substrate and overlay layer after exposure to elevated temperature. The results agree with previous findings in the literature [21]. The better performance is due to the development of a control crack by SF, which reduces the stress relaxation phenomenon and the size of new pores [32]. In addition, thermal mismatch of PP fiber expansion and concrete expansion leads to development of thermal stresses as well as microcracking, along with the increase in permeability due to melting and burning of PP fibers. These two mechanisms together mitigate spalling in concrete. Moreover, these actions increase microcracking which releases the pore pressure [64, 65].

Furthermore, the effect of using steel reinforcement on the behavior of composite slab under elevated temperature was studied through composite slab specimens GS-N and GS-NR strengthened in tension side by BFSC-SF layer with and without steel reinforcement, respectively. Figure 9b depicts the load deflection relationships for the two slabs. From this figure, it can be indicated that the slab specimen GS-NR showed brittle failure as the slab reached the ultimate load and the load decreased rapidly. This decrease is attributed to the steel reinforcement which distributes the stress along the slab span and delays the crack formation which helped in increasing the capacity of the strengthened RC slab [12]. The reduction in cracking and ultimate loads are 62.5% and 61.5%, respectively compared to slab GS-N. When comparing the two composite slabs GS-N and GS-NR with single concrete slab which whole thickness cast with HPC mix BFSC-SF (slab GS), the two composite slabs suffered more deterioration with a decrease of (41.4%, 78%) and (45%, 79%) in cracking and ultimate loads, respectively. This decrease may be resulted from the weak bond between the two concrete layers under elevated temperature exposure [42].

According to the fire exposure side, slab specimens FP-N and FP-NC (the strengthening layer cast with HPC mix FAC-PPF in tension) exposed to elevated temperature from the tension and compression sides, respectively, are compared to slab specimen N as shown in Figure 9b. The results illustrated that the two slab specimens had a similar trend, suffering a decrease in load after reaching ultimate load, but staying higher than slab specimen N. From the results presented in Figure 8 and Table 6, it can be concluded that slab specimen FP-N provides higher cracking and ultimate loads than slab specimens FP-NC and N. The cracking and ultimate loads for slab FP-N increased by (29.7%, 93.5%) and (18%, 79%) as compared with slab specimens FP-NC and N, respectively. This is attributed to the fact that the concrete mix FAC-PPF has low thermal properties, which reduced the reinforcement temperature and reduced the temperature transfer to the layer cast with NSC. Although composite slabs FP-N and FP-NC had an increase in structural properties as compared to slab specimen N, they couldn’t satisfy the cracking and ultimate loads of single concrete slab FP. The cracking load decreased by 11% and 32% for slab specimens FP-N and FP-NC, respectively, as compared to single slab specimen FP, while the ultimate load decreased by 12% and 25%, respectively.

With regard to the effect of strengthening side, slab specimen strengthening in compression side N-FSP is compared with slab strengthening in tension side FSP-N, as depicted in Figure 9c. Slab N-FSP recorded a decrease in cracking and ultimate loads of 18.5% and 15.9%, respectively, compared to slab FSP-N. On the other hand, slab N-FSP recorded 22 kN and 26.68 kN for cracking and ultimate loads, respectively, with a significant increase of 77.4% and 81.7% compared to slab specimen N. The results agreed with Naghibdehi et al. [11], who concluded that the addition of a topping layer of steel fiber reinforced concrete to RC slab increased the cracking and ultimate loads at ambient temperature. This improvement is due to the chemical reaction of HPC that fills the pore in the interface between the two concrete layers and produces a shear connector that is able to enhance the interface bond strength, as discussed by Mansour and Fayed [63].

Regarding the efficiency of bond connection of slab specimens, composite slab FS-N with shear stud and FS-NE with epoxy bond are compared (see Figure 9b), as well as composite slab N-FSP is compared to slab N-FSPE (see Figure 9c). It is clear that the shear stud officiously increased the cracking and ultimate loads with an increase of 170.7%, 152.71%, and 100%, 123.83%, for slab specimens FS-N and N-FSP in comparison with slab specimens FS-NE and N-FSPE, respectively. This increase is due to the performance of the strengthened structures, which strongly depend on the interaction of the two concrete layers. The performance of the interface can be improved by using a shear stud, as mentioned by Fernandes et al. [40]. On the other hand, slab specimens FS-NE and N-FSPE failed to achieve the cracking and ultimate loads of slab specimen N, with decreases of 46.4%, 35%, and 11.3%, 18.8%, respectively, with respect to slab specimen N. This decrease is attributed to the loss of bonding between the two layers of concrete after exposure to elevated temperature as mentioned in the previous [40].

3.2.2 Ductility Index, Stiffness and Toughness

The results of ductility, stiffness, and toughness for different tested RC slabs are given in Table 6 and plotted in Figures 10 and 11.

3.2.2.1 Single-Concrete Slabs

Table 6 displays that the different types of single slab concrete significantly raised the structural properties, as slab G recorded the highest ductility and toughness with an increase of 63% and 355% relative to slab specimen N, while slab specimen H recorded the highest stiffness of 5.76 kN/mm with a ratio of 85% higher than slab specimen N. The better performance of slab G is attributed to the GGBFS, which recorded the smallest temperature throw concrete slab thickness in addition to the highest residual properties after exposure to 600°C, as reported by Ghazy et al. [29].

The positive effect of fiber was very evident in ductility, stiffness, and toughness with recoded increases of (73.7%, 81%, 63%, 89.9%), (62%, 106%, 51%, 97%), and (317.8%, 339%, 318%, 396%) for slab specimens FS, FP, FSP, and GS, respectively. The results agreed with Ghazy et al. [18].

3.2.2.2 Composite Slabs

Figure 11 illustrates the percentage of variation in ductility, stiffness, and toughness for different composite slabs as compared to single slab N and the corresponding HPC single concrete slab specimens.

Regarding the inclusion of different types of fibers, RC composite slab specimens with PPF, SF, and PPF+SF in slab specimens FS-N, FP-N, FSP-N, and GS-N exhibited better performance in terms of ductility, stiffness and toughness than slab specimen N, with increases of 34% to 86.9%, 19.5% to 157%, and 138% to 335%, respectively, as shown in Figure 11. It can be noted that slab FSP-N displayed the highest ductility index, stiffness, and toughness compared to slab specimen N, with an increase of 86.9%, 157.2%, and 335.7%, respectively. This is because SF improves the ductility of slabs exposed to fire (Ghaz et al. [18] and Ahmed et al. [62]).

Whereas composite slab specimen without using the steel reinforcement GS-NR resulted in a decrease of (29.9%, 37.3%, 87.6%) and (2.6%, 25%, 70.4%) in ductility, stiffness, and toughness relative to slab specimens GS-N and N, respectively.

On the other hand, the use of epoxy resin to prepare the bonding surface of the layers of RC composite slabs (FS-NE and N-FSPE) recorded low performance compared to slab specimen N and the corresponding single HPC slabs due to the deterioration of the epoxy bond under elevated temperatures.

3.3 Prediction of the Ultimate Limit Capacity of RC Slab Specimens

To predict the flexural capacity of single concrete and composite slabs, the section analysis method was used. The sectional analysis method, which is based on strain compatibility and force equilibrium conditions, is one approach for predicting and analyzing the flexural responses of the RC slab strengthened with HPC [66,67,68]. In this method, the RC slab cross section was divided into M slices as presented in Figure 12, and for each slice, the temperature rise by exposure to fire was determined according to Lie and Leir [69], and then the residual mechanical properties were defined using Ghazy et al. [29]. The suggested analysis considers the effects of both fibers and high strength concrete according to MC2010 [70], where the stresses in the compression zone can be calculated considering two factors \(\lambda\) and \(\eta\) (Eqs. 3, 4) which define the height of the compressive zone and the effective strength, respectively, as follows:

The tensile strength of cracked HPC containing steel fiber is taken into account assuming uniform distribution stress fti and can be calculated according to Qi et al. [71] as follows, Equation 5.

For unit width of slab b, the compression force can be calculated according to Erdem [72], Equation 6.

The tension force (T) equals the force in steel reinforcement rebar (TS) in all slabs except slabs cast with HPC containing steel fiber, where the effect of steel fiber is taken into consideration (TFS) according to Teng and Khayat [66] by using Eqs. 7–10.

The location of the neutral axis can be specified by using the equilibrium force of the cross section, as shown in Equation 11:

The flexural load capacity Pu can be determined using Eqs. 12 to 14.

where Mu is the ultimate flexural moment, N is the axial load of concrete in compression, \({f}_{cki}^{^{\prime}}\) is the residual compressive strength at ith layer,\({f}_{y}\) is the yield strength of reinforcement at room temperature, \({k}_{s}\) is the reduction factor with the temperature increase in reinforcement according to EN 1993 [73, 71], \({f}_{ti}\) is the residual tensile strength at ith layer, \(\rho\) is the volume fraction of steel fiber, l and d are length and diameter of steel fiber, b unit width of slab.

For analytical analysis, the following assumptions are taken into account:

-

Plain section before bending remain plane after bending.

-

Prefect bond between reinforcement and concrete, concrete substrate and concrete overlay.

-

Temperature in reinforcement is equal to the temperature of surround concrete.

-

Concrete in tension zone is neglected except concrete containing steel fiber.

Table 7 displays the predicted flexural capacity as compared to the experimental results and the ratio between the experimental and predicted flexural capacities. It is clear from the table that the prediction of flexural capacity by using MC2010 [70] is suitable for single concrete slabs cast with HPC with and without steel fibers, where the ratio between experimental and predicted values varied from 7% to 20%. On the other hand, the predicted flexural capacity of RC slab cast with NSC at room temperature and after exposure to elevated temperature is underestimated by approximately 30% and 40%, respectively.

The flexural capacity calculated by using equations is excellent for composite slabs, except slabs strengthened with blast furnace slag concrete layer (G-N and GS-N) and in the case of epoxy resin (FS-NE and N-FSPE). The variance between the predicted and experimental flexural capacity is 0 to 20%, where the resulting theoretical flexural capacity underestimates the experimental result of composite slabs G-N and GS-N by 44% and 39%, respectively. This large variance is due to the fact that the equation doesn't take the difference in thermal expansion between the two concrete layers into consideration. Whereas the differences between the experimental and theoretical results for composite slabs N-FSPE and FS-NE are 55% and 70%, respectively. Note that using ft is more appropriate to estimate the flexural capacity of single concrete and composite slabs cast with HPC containing steel fiber, the results agree with Teng and Khayat [66] and Jafarzadeh and Nematzadeh [74].

3.4 Crack Patterns and Mode of Failure

3.4.1 Pre-loading After Heating and Cooling Phase

The cracking pattern of slab specimens exposed to a temperature of 600°C for 2 h is presented in Figure 13. From the figure, it can be noticed that the slab specimen N recorded a few fine cracks on the exposed surface, while no cracks appeared on the unexposed surface, as shown in Figure 13a. On the other hand, HPC slabs did not record cracks on the surface exposed to fire except slab specimen FS, which showed a number of fewer cracks on the exposed surface as depicted in Figure 13b. This is attributed to SF, which prevents the vapor water from escaping into the atmosphere, which causes cracks [38].

For composite RC slabs exposed to elevated temperature up to 600°C for 2 h, there were not cracks appear on concrete slab surface except composite slabs G-N, GS-N, FS-NE and N-FSPE. For composite slabs G-N and GS-N, there is a fine crack in the interface between the two concrete layers as presented in Figure 13c. This crack may be is due to the difference in the thermal expansion of NSC and BFSC. Where composite slabs FS-NE and N-FSPE which used epoxy resin in bonding the two concrete layers, the first crack was observed on the interface between the two concrete layers after 20 min to 30 min when the temperature on the interface became 90°C to 100°C. This is because epoxy reaches the glass transition temperature (Tg) as mentioned by [44]. After 90 min, epoxy is evaporated and a hot brown smook was escaped through the interface crack. After the composite slab cooled down to room temperature, slab specimens FS-NE and N-FSPE showed a large crack on the interface and no seperation occurred as shown in Figure 13d and e.

3.4.2 Post-loading

Similar crack patterns were recoreded for both of the control slab specimen N25 and the heated one N under flexural load, but the heated slab N generated much more and wider cracks. It was shown in tests that the first flexural crack occurred at the mid span of the slab at a load of 18 and 12.4 kN for slab specimens N25 and N, respectively, then more flexural cracks appeared as the load increased. The decrease in the first crack load for slab specimen N is attributed to the tensile strength deterioration with increasing temperature. The final failure modes of the specimens are shown in as shown in Figure 14.

For single HPC slabs H, F, G, FS, FP, FSP, and GS, the observation showed that there were two mean vertical crack patterns on the tension side that propagated with increasing load towards the compression zone until the crushing of concrete in the compression zone. There was a small variance in the cracking load recorded, as it was observed in the range 25 kN to 27.9 kN. This is because of the strong bond between HPC and reinforcement [12]. The crack propagated in compression side under point load because of the yielding of reinforcement. For slab specimens FS, FP, FSP, and GS, more minor cracks were shown in the middle third of the RC slab between the two mean cracks with increasing load, as presented in Figure 14.

The failure patterns for all composite slabs after load are presented in Figure 14. There is a significant difference in cracking load (6 kN to 27 kN) for composite slabs. The large variance is due to the bond technique between the two concrete layers, and the presence of reinforcement, where the temperature had an adverse affect on the shear transfer strength of concrete, and using the shear stud technique led to improve the shear transfer strength in the interface between the two concrete layers, as mentioned by Ahmad et al. [42]. With the increasing load, a sliding of the upper concrete layer was observed, and flexural cracks were propagated throughout the slab soffit. In addition, diagonal cracks initiated from the tension side and propagated towards the compression side. This is due to the fact that the shear strength of concrete decreased with the increase in temperature. Also, cracks occurred above support in the substrate layer. Slab specimen FSP-N showed the highest cracking load, which equaled 27 kN with a 92.8% increasing ratio as compared to slab specimen N. This proved a good bond between the two concrete layers. The efficiency of the bond technique used to achieve a good bond between concrete layers was also demonstrated by other researchers [10, 11, 41]. As the load increased, the crack widened and propagated throw the two concrete layers toward the compression zone. Also, longitudinal cracks appeared at the reinforcement and on the interface between the two concrete layers.

Slab specimen GS-NR showed one main crack in the tension side propagated at a load of 6 kN, when the slab reached its maximum load of 6.9 kN, a rapid increase in deflection was observed.

4 Conclusions

This study focused on the flexural behavior of RC slab specimens cast with conventional normal strength conrete (NSC) and strengthened with a layer of high-performance conrete (HPC) after exposure to elevated temperature. The investigated parameters include concrete types, fiber types, reinforcement ratio, side of exposure to elevated temperature, strengthened side, and the method of bonding the composite layers. Based on the results and analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

No spalling in either single slabs or composite slabs. In addition, the temperature distribution in HPC single slabs and composite slabs is lower than the temperature distribution in single slab cast with NSC.

-

The use of polypropylene fibers plays an important role in the temperature distribution of composite slabs. Composite slab cast with fly ash and polypropylene fiber displayed a higher temperature variation between the reinforcing steel and the inner parts compared to composite slab cast with steel fiber or hybrid fibers.

-

Single slab cast with NSC showed more deterioration after exposure to elevated temperature, as the cracking load, ultimate load, ductility, stiffness, and toughness decreased by 31.11%, 54.52%, 17.53%, 26%, and 74% compared to NSC at 25°C, respectively.

-

Generally, strengthening the RC slab in tension or compression with HPC significantly improved slab performance after exposure to elevated temperature compared to a single slab cast with NSC, with relative increases in cracking laod, ultimate load, ductility, stiffness, and toughness of (21% to 117%), (22.5% to 116%), (23.7% to 86.9%), (8% to 157%), and (17% to 335.6%), respectively.

-

The highest cracking load, ultimate load capacity, stiffness, toughness, and ductility index was recoded for composite slab cast with fly ash concrete and using hybrid fibers in tension side (slab FSP-N) compared to a single slab specimen cast with NSC with increasing ratios of 92.8%, 116%, 157%, 335, and 86.9%, respectively.

-

Composite slab without steel reinforcement showed the least performance as compared to slab with steel reinforcement.

-

The direction of the fire clearly affects the flexural behvior of composite slab, as the composite slab cast with fly ash concrete and polypropylene fibers in the tension side proves its efficiency in case of exposure to elevated temperature from the tension side more than from the compression side.

-

Shear studs efficiently contribute to enhancing the flexural behavior of the composite slab after exposure to an elevated temperature, while the use of epoxy resin is not suitable in the case of elevated temperature.

-

All composite RC slabs showed a decrease in flexural properties after exposure to elevated temperature compared to the single slab cast with the same types of HPC, except the slab specimen cast with hybrid fibers, which showed a significant improvement.

-

The theoretical models used appear to be qualified for predicting the flexural properties with reasonable accuracy for slab specimens cast with HPC. Modelling revealed that HPC incorporating fibers and fly ash in addition to being cost-effective can be effective for expansion in a certain direction serving some environmentally friendly construction applications, which is attributed to the remarkable improvement in the flexural properties of RC composite slabs when subjected to fire.

-

Additional parameters, such as fiber content, HPC thickness, and geometry of RC members, should also be evaluated to comprehensively explore the potential of HPC material for composite RC members exposed to fire.

Abbreviations

- HPC :

-

High performance concrete

- HSC :

-

High strength concrete

- FAC :

-

Fly ash concrete

- BFSC :

-

Blast furnace slag concrete

- SF :

-

Steel fiber

- PPF :

-

Polypropylene fiber

- GGBFS :

-

Ground granulated blast furnace slag

- FAC-SF :

-

Fly ash concrete with steel fiber

- FAC-PPF :

-

Fly ash concrete with polypropylene fiber

- FAC-(SF+PPF) :

-

Fly ash concrete with steel and polypropylene fibers

- BFSC-SF :

-

Blast furnace slag concrete with steel fiber

- P cr :

-

Cracking load

- P u :

-

Ultimate load

- \(\Delta_{f}\) :

-

Deflections at failure load

- P 75% :

-

The load level at 75% of the peak load

- Δ 75 % :

-

Mid-span deflection at 75% of the peak load

- M :

-

Number of slices

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Factor define the height of the compressive zone

- \(\eta\) :

-

The effective strength factor

- f t :

-

Tensile strength of concrete containing steel fiber

- \(f_{ck}^{^{\prime}}\) :

-

The residual compressive strength

- \(\rho\) :

-

Volume fraction of steel fiber

- \(l\) :

-

Length of fiber

- \(d\) :

-

Diameter of fiber

- N :

-

The axial load of the concrete in the compression zone

- \(T_{s}\) :

-

The force in steel reinforcement rebar

- \(T_{FS}\) :

-

The tension force in concrete containing steel fiber

- \(f_{y}\) :

-

Yield strength of reinforcement at room temperature

- \(k_{s}\) :

-

The reduction factor with the temperature increase

- \(M_{u}\) :

-

The ultimate moment capacity

- \(P_{th}\) :

-

The predicted flexural capacity

- L :

-

The RC slab span

References

Mindeguia J-C, Pimienta P, Noumowé A, Kanema M (2010) Temperature, pore pressure and mass variation of concrete subjected to high temperature—experimental and numerical discussion on spalling risk. Cem Concr. Res 40(3):477–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.10.011

Eurocode 2 (2004) Design of concrete structures, part 1–2: general rules-structural fire design ENV 1992-1-2/UK: CEN. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels

Kodur VK, Dwaikat MB (2008) Effect of fire induced spalling on the response of reinforced concrete beams. Int J Concr Struct Mater 2(2):71–81. https://doi.org/10.4334/IJCSM.2008.2.2.071

Kodur V, Yu B, Dwaikat M (2013) A simplified approach for predicting temperature in reinforced concrete members exposed to standard fire. Fire Saf J 51(56):39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2012.12.004

Khaliq W, Kodur V (2011) Thermal and mechanical properties of fiber reinforced high performance self-consolidating concrete at elevated temperatures. Cem Concr Res 41:1112–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.06.012

Nguyen T, Thai H, Ngo T (2023) Effect of steel fibers on the performance of an economical ultra-high strength concrete. Struct Concr 24:1–15

Conforti A, Trabucchi I, Tiberti G et al (2019) Precast tunnel segments for metro tunnel lining: a hybrid reinforcement solution using macro-synthetic fibers. Eng Struct 199:109628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.109628

Khalighi A, Izadifard RA, Zarifian A (2020) Role of macro fibers (steel and hybrid-synthetic) in the residual response of RC beams exposed to high temperatures. SN Appl Sci 2:1981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03790-z

Martinola G, Meda A, Plizzari G et al (2010) Strengthening and repair of RC beams with fiber reinforced concrete. J Cem Concr Compos 32:731–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2010.07.001

Haddad RH, Al-Mekhlafy N, Ashteyat AM (2011) Repair of heat-damaged reinforced concrete slabs using fibrous composite materials. J Constr Build Mater 25:1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.09.033

Naghibdehi MG, Sharbatdar MK, Mastali M (2014) Repairing reinforced concrete slabs using composite layers. Mater Des 58:136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2014.02.015

Basha A, Fayed S, Mansour W (2020) Flexural strengthening of RC one way solid slab with strain hardening cementitious composites (SHCC). Adv Concr Constr 9(5):511–527. https://doi.org/10.12989/acc.2020.9.5.511

Xiao J-ZH, Li J, Jiang F (2004) Research on the seismic behavior of HPC shear walls after fire. Mater Struct 37:506–512

Dwaikat MB, Kodur VK (2010) Fire induced spalling in high strength concrete beams. Fire Technol 46(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-009-0088-6

Almeshal I, Abu Bakar BH, Tayeh BA (2022) Behaviour of reinforced concrete walls under fire: a review. Fire Technol 58:2589–2639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-022-01240-3

Ghazy MF, Abd Elaty MA, Zalhaf NZ (2021) Prediction of temperature distribution and fire resistance of RC slab using artificial neural networks. Int J Struct Eng 11(1):1–18

d’Entremont FP, Poitras GJ (2022) Bending strength of composite slabs exposed to fire at an early age. Fire Technol 58:3509–3527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-022-01315-1

Ghazy MF, Abd Elaty MA, Zalhaf NM (2022) Modeling the performance of reinforced concrete slabs cast with high performance concrete under fire. Innov Infrastruct Solut 7:2

Heikal M, El-Didamony H, Sokkary TM (2013) Behavior of composite cement pastes containing microsilica and fly ash at elevated temperature. Constr Build Mater 38:1180–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.09.069

Khaliq W, Kodur V (2018) Effectiveness of polypropylene and steel fibers in enhancing fire resistance of high-strength concrete columns. J Struct Eng 144(3):1981. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0001981

Algourdin N, Pliya P, Beaucour A-L et al (2020) Influence of polypropylene and steel fibres on thermal spalling and physical-mechanical properties of concrete under different heating rates. Constr Build Mater 259:119690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119690

Kodur VKR (2000) Spalling in high strength concrete exposed to fire––concerns, causes, critical parameters and cures. In: ASCE structures congress proceedings. Philadelphia, pp 1–8

Shariq M, Khan AA, Masood A et al (2021) Experimental and analytical study of flexural response of RC beams with steel fibers after elevated temperature. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Civil Eng 45:611–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-020-00408-7

Poon C-S, Azhar S, Anson M et al (2001) Comparison of the strength and durability performance of normal-and high-strength pozzolanic concretes at elevated temperatures. Cem Concr Res 31(9):1291–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00580-4

Khaliq W, Kodur V (2013) Behavior of high strength fly ash concrete columns under fire conditions. Mater Struct 46:857–867. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-012-9938-7

Khan MS, Abbas H (2014) Effect of elevated temperature on the behavior of high volume fly ash Concrete. KSCE J Civ Eng 19(6):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-014-1092-z

Tanyildizi H, Coskun A (2008) The effect of high temperature on compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of structural lightweight concrete containing fly ash. Constr Build Mater 22(11):2269–2275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.07.033

Babalola OE, Awoyera PO, Le DH et al (2021) A review of residual strength properties of normal and high strength concrete exposed to elevated temperatures: impact of materials modification on behaviour of concrete composite. Constr Build Mater 296:123448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123448

Ghazy MF, Abd Elaty MA, Zalhaf NZ (2022) Mechanical properties of hpc incorporating fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag after exposure to high temperatures. Period Polytech Civ Eng. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPci.19751

Xiao J, Falkner H (2006) On residual strength of high-performance concrete with and without polypropylene fibres at elevates temperatures. Fire Saf J 41:115–121

Behnood A, Ghandehari M (2009) Comparison of compressive and splitting tensile strength of high-strength concrete with and without polypropylene fibers heated to high temperatures. Fire Saf J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2009.07.001

Ding Y, Azevedo C, Aguiar J, Jalali S (2012) Study on residual behaviour and flexural toughness of fibre cocktail reinforced self compacting high performance concrete after exposure to high temperature. Constr Build Mater 26(1):21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.04.058

Abdul-Rahman M, Al-Attar AA, Hamada HM et al (2020) Microstructure and structural analysis of polypropylene fibre reinforced reactive powder concrete beams exposed to elevated temperature. J Build Eng 29:101167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.101167

Du H, Zhang M (2020) Experimental investigation of thermal pore pressure in reinforced C80 high performance concrete slabs at elevated temperatures. Constr Build Mater 260:120451

Jafarzadeh H, Nematzadeh M (2020) Evaluation of post-heating flexural behavior of steel fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete beams reinforced with FRP bars: experimental and analytical results. Eng Struct 225:111292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111292

Haddad RH, Al-Saleh RJ, Al-Akhras NM (2008) Effect of elevated temperature on bond between steel reinforcement and fiber reinforced concrete. Fire Saf J 43:334–343

Yermak N, Pliya P, Beaucour A-L et al (2017) Influence of steel and/or polypropylene fibres on the behaviour of concrete at high temperature: spalling, transfer and mechanical properties. Constr Build Mater 132:240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.120

Monte FL, Felicetti R, Rossino C (2019) Fire spalling sensitivity of high-performance concrete in heated slabs under biaxial compressive loading. Mater Struct. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-019-1318-0

Randl N (2013) Design recommendations for interface shear transfer in fib Model Code 2010. Struct Concr 14:230–241

Fernandes H, Lúcio V, Ramos A (2017) Strengthening of RC slabs with reinforced concrete overlay on the tensile face. Eng Struct 132:540–550

Xu Q, Chen L, Li X et al (2020) Comparative experimental study of fire resistance of two-way restrained and unrestrained precast concrete composite slabs. Fire Saf J 18:103225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2020.103225

Ahmad S, Bhargava P, Chourasia A et al (2020) Shear transfer strength of uncracked concrete after elevated temperatures. J Struct Eng 146:7

Xiao J, Li Z, Li J (2014) Shear transfer across a crack in high-strength concrete after elevated temperatures. Constr Build Mater 71:472–483

Blontrock H, Taerwe L, Vandevelde P (2000) Fire tests on concrete beams strengthened with fibre composites laminates. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International PhD Symposium in Civil Engineering. Vienna, Austria. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-130382

EN 196-1 (2016) Cement—part 1: methods of testing cement-part 1: determination of strength. British Standards Institution, London

ES 4756 (2013) Cement part (1) composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements. British Standards Institution, London

ASTM-C127-01 (2017) Standard test method for density, relative density (specific gravity), and absorption of coarse aggregate. ASTM International, Wes Conshohocken

ASTM C128-01 (2017) Standard test method for density, relative density (specific gravity), and absorption of fine aggregate. ASTM International, West Conshohocken

ASTM C29/C29M-07 (2010) Standard test method for bulk density (“unit weight”) and voids in aggregate. ASTM International, West Conshohocken

ASTM C136/C136M-19 (2020) Standard test method for sieve analysis of fine and coarse aggregates. ASTM International, West Conshohocken

ASTM C494/C494M (2019) Standard specification for chemical admixtures for concrete. ASTM, West Conshohocken

Gao D, Yan D, Li X (2012) Splitting strength of GGBFS concrete incorporating with steel fiber and polypropylene fiber after exposure to elevated temperatures. Fire Saf J 54:67–73

BS EN 12390-3 (2019) Testing hardened concrete compressive strength of test specimens. British Standards Institution, London

BS EN 12390-6 (2009) Testing hardened concrete tensile splitting strength of test specimens. British Standards Institution, London

BS EN 12390-5 (2019) Testing hardened concrete flexural strength of test specimens. British Standards Institution, London

ACI Committee 318 (2014) Building code requirements for structural concrete (ACI318R-14). American Concrete Institute, Michigan

Coz-Díaz JJ, Martínez EJ, Martínez MA et al (2020) Comparative study of light weight and normal concrete composite slabs behaviour under fire conditions. Eng Struct. 207:110196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.110196

Priestley MJN, Seible F, Calvi GM (1996) Seismic design and retrofit of bridges. Wiley, New York

Mansour W, Fayed S (2021) Flexural rigidity and ductility of RC beams reinforced with steel and recycled plastic fibers. Steel Compos Struct 41(3):317–334. https://doi.org/10.12989/SCS.2021.41.3.317

Akca AH, Özyurt N (2020) Post-fire mechanical behavior and recovery of structural reinforced concrete beams. Constr Build Mater 253:119188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119188

Turker K, Hasgul U, Birol T et al (2019) Hybrid fiber use on flexural behavior of ultra-high performance fiber reinforced concrete beams. Compos Struct 229:111400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111400

Ahmed RH, Abdel-Hameed GD, Farahat AM (2016) Behavior of hybrid high-strength fiber reinforced concrete slab-column connections under the effect of high temperature. HBRC J 12:54–62

Mansour W, Fayed S (2021) Effect of interfacial surface preparation technique on bond characteristics of both NSC-UHPFRC and NSC-NSC composites. Structure 29:147–166

Kodur V, Banerji S (2021) Modeling the fire-induced spalling in concrete structures incorporating hydro-thermo-mechanical stresses. Cem Concr Compos 117:103902

Li Y, Tan KH, Yang EH (2019) Synergistic effects of hybrid polypropylene and steel fibers on explosive spalling prevention of ultra-high performance concrete at elevated temperature. Cem Concr Compos 96:174–181

Teng L, Khayat KH (2022) Effect of overlay thickness, fiber volume, and shrinkage mitigation on flexural behavior of thin bonded ultra-high-performance concrete overlay slab. Cem Concr Compos 134:104752

Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Yeseta M et al (2019) Flexural behaviors and capacity prediction on damaged reinforcement concrete (RC) bridge deck strengthened by ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) layer. Constr Build Mater 215:347–359

Zhou T, Sheng X (2022) Experimental study of flexural performance of UHPC–NC laminated beams exposed to fire. Materials 15:2605

Lie TT, Leir G (1979) Factors affecting temperature of fire-exposed concrete slabs. Fire Mater 3(2):74–79

FIB (2013) Fib model code for concrete structures 2010. Ernst Sohn Publication, New York, p 434

Qi J, Cheng Z, Wang J, Zhu Y, Li W (2020) Full-scale testing on the flexural behavior of an innovative dovetail UHPC joint of composite bridges. Struct Eng Mech 75:49–57

Erdem H (2010) Prediction of the moment capacity of reinforced concrete slabs in fire using artificial neural networks. Adv Eng Softw 41:270–276

EN 1993-1-2 (2005) Eurocode 3: design of steel structures-part 1–2: general rules-structural fire design. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels

Jafarzadeh H, Nematzadeh M (2020) Evaluation of post-heating flexural behavior of steel fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete beams reinforced with FRP bars: experimental and analytical results. Eng Struct 225:111292

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff of the Properties of Materials laboratory—Faculty of Engineering—Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt for the help they offered during various stages in conducting this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghazy, M.F., Abd Elaty, M.A. & Zalhaf, N.M. Performance of Normal Strength Concrete Slab Strengthened with High-Performance Concrete After Exposure to Elevated Temperature. Fire Technol 59, 2415–2453 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-023-01439-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-023-01439-y