Abstract

Did consumers change their payment behaviour after being exposed to a public campaign that encouraged them to use their debit cards more often? We analysed the impact of such a campaign that started in 2007, using debit card transaction data between 2005 and 2013. The overall results show positive effects of the national campaign to promote debit card usage, both in the short and in the long run. The results suggest that high campaign intensity aimed at consumers had a positive impact, as did a focus on certain large retail chains. Interventions aimed at increasing debit card acceptance by retailers were effective to some extent. Providing information to retailers about the benefits of debit card acceptance led to higher card acceptance, but no proof was found for the effectiveness of financial incentives for retailers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

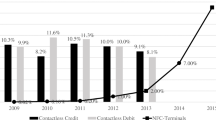

In the Netherlands almost all adults have a current account and a debit card that they can use for cash withdrawals and for making POS payments, both of which are free of any transaction fees. Reward programmes for debit or credit card payments are uncommon. Apart from cash and debit cards, people can also use credit cards or prepaid cards; these payments represent only a few percent of all POS payments.

The Forum was instigated in 2002 at the request of the Minister of Finance to contribute to a socially efficient organisation of the Dutch retail payment system. It was established in 2003. The Forum represents both providers and users of payment systems, including retailers’ and banks’ umbrella organisations, the Consumentenbond consumer interest association and elderly and disabled people’s organisations.

Jonker (2013) showed that the threshold level had dropped to EUR 3.06 between 2002 and 2009. So, from 2009 onwards debit card usage was the most cost–effective option for almost any transaction amount.

This number does not include street trading and catering, which have relatively low acceptance rates.

It is, however, difficult to say by how much. Bolt et al. (2010) show that in 2006, 22% of the retailers applied a surcharge, most of them owners of small shops in which consumers make relatively few payments. According to HBD (2011), the percentage of retailers that applied a surcharge was 5% in 2009, dropping to 3% in 2010 and 2% in 2011. In 2009, HBD also asked retailers whether they had applied a surcharge on card payments in the past. Of those that did not do so in 2009, 8% said they had done so 1–2 years earlier, and another 10% said they had done so more than 2 years earlier. This implies that around 12–13% of the retailers applied a surcharge in 2007 (HBD 2009). The methodologies of the studies were different, however. HBD surveyed retail establishments (including individual shops belonging to a larger chain), while Bolt et al. (2010) surveyed independent retailers only. Also, in contrast to the other two sources, HBD did not include catering establishments.

The DNB household survey is held on a recurring basis among about 2000 Dutch households that are members of the CentERpanel, which is managed by the CentERdata research institute. The panel members are fairly representative of the Dutch-speaking population.

It should be noted, however, that perceived costs do not seem to be an important driver of payment behaviour in the Netherlands, with user-friendliness, safety and speed being more relevant (Cruijsen van der and Plooij 2015). Moreover, although the decline in surcharging may have had an effect on consumer payment behaviour, this effect is likely to have been a gradual one, any effect of which on debit card usage would be reflected in the positive trend in the number of debit card payments rather than in the effects of interventions that took place in specific weeks.

Ideally, we would have used an experimental approach to examine the impact of the campaign on consumers’ debit card usage, with one group living in the Netherlands and receiving the treatment (public campaign exposure) and another group living outside the Netherlands and not receiving the treatment (control group). Unfortunately, we could not do this, as we do not have weekly debit card data for countries that could have acted as a control group, i.e. countries which are comparable to the Netherlands with respect to debit card usage and debit card acceptance, such as Belgium or the UK.

Annual figures on the number of debit card payments provided by Equens may differ from statistics provided by the DPA, due to differences in reporting transaction data. However, the trends in card usage are similar.

Google Trend is a public web facility of Google Inc., based on Google Search, which provides a normalised data-series reflecting the relative search intensity for a specified search term relative to the highest intensity in a specific period. The user can specify the region and time period.

An even better variable for assessing the impact of the public campaign on debit card usage would have been the share of debit card payments in all POS payments made by Dutch consumers. Unfortunately, such information is not available as cash payments are not registered by banks or processed by ACHs, unlike card payments.

In order to examine the impact of a campaign it would be best to evaluate its impact on all four stages of the consumers’ decision process, i.e. attention, interest, desire and action (Strong 1925). However, we only have suitable weekly data on the last stage. There is no data about the campaigns’ impact on the other three stages.

Next to impulse and step effects, the interventions may influence the slope in the time trend for the number of debit card transactions; i.e. they may influence the natural development in debit card usage. It is conceivable that interventions lead to a higher growth rate in debit card usage. We conducted several statistical tests to assess whether the slope in the time trend was influenced by the public campaign or its interventions. The tests did not reject the hypothesis that the slope in the time trend had remained stable since the start of the campaign. In addition, the hypothesis that clusters of interventions had affected the slope in the time trend in the long run could also not be rejected. Only cluster 7 had a significant impact on the slope in the time trend but its impact was neutralised by the significant negative effect of cluster 8 on the slope. The hypothesis that the sum of these two effects equals zero could not be rejected at the 5% level.

We did not use monthly step functions as the inclusion of both impulse and step functions in the monthly models resulted in serious multicollinearity. In the monthly model we used lagged effects of the impulses to capture long term effects.

Christmas holidays, Spring holidays, May holidays, Summer holidays, Autumn holidays.

New Year’s Day, Valentine’s day (14 February), Koninginnedag (30 April), Sinterklaas (5 December), Christmas Day and Boxing Day, New Year’s Eve, Easter, Whitsun, Ascension Day, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day.

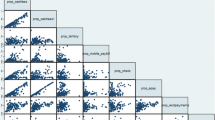

Initially, we estimated a simple VAR model containing the endogenous variables d(log(DCm)), d(log(Terminalsm)), d(log(GT_pinpasm)) and d(log(Retail_salesm)) as endogenous variables. According to Granger Causality / Block Wald test the hypothesis that d(log(DCm)) is exogenous cannot be accepted (p = 0.000), but the hypotheses that d(log(Terminalsm)) d(log(retail_salesm)) and d(log(GT_pinpastm) are exogenous are accepted at the 5% level of significance. These results indicate that only one of the four variables can be considered as endogenously determined by the other three. We therefore decided to continue using single time series models, as it provides more flexibility in the specification of the model per dependent variable than (S)VAR-analysis.(VAR) estimation results are presented in Table 7 in Appendix 4.

We used a lag length of three, following the results on the optimal lag length from the VAR analysis described in Appendix 4.

We did not include step functions in the monthly model as the long-term dynamics are captured by means of the lag structure of the model.

The illustration draws heavily on Berndt (1991, pp. 375–376).

Hernandez et al. (2017) show that consumers tend to use the means of payment that they think helps them best control their spending. Arango et al. (2015) stress the importance of cash with respect to limit overspending; they find that “those concerned about overspending tend to shun credit cards and rely more on cash, but not on debit cards”.

Diagnostic checks revealed that the residuals contained some heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. Including AR and MA terms partly solved the problem, but not completely. The hypothesis of no autocorrelation was not rejected according to the Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test (F statistic, p = 0.11), but the correlogram up to 36 lags showed some small though significant autocorrelation in lags 3 and higher. Furthermore, the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey rejected the hypothesis of no heteroscedasticity (F-statistic, p = 0.01). We therefore decided to use the robust Heteroskedastic and Autocorreled Consistent (HAC) standard errors by Newey-West, which provide a consistent estimation of the covariance matrix in case of heteroscedasticity or autocorrelation of unknown form.

In order to check whether consumer search affects card usage after 2 or more months, we ran a Wald redundancy test on d(log(GT_pinpasm)) for lags 2 and 3. The test indicated that they were not jointly significant (p = 0.57), therefore we did not include them in the set of explanatory variables.

Diagnostic checks revealed that the residuals were autocorrelated. Including AR(1), AR(2) and AR(3) terms and controlling for two outliers (November 2005 and February 2006) solved a large part of this problem. The hypothesis of no autocorrelation was not rejected according to the Breusch- Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test (F statistic, p = 0.15), and the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey did not reject the hypothesis of no heteroscedasticity (F-statistic p = 0.32). However, the correllogram up to 36 lags showed some remaining serial correlation between lags 3–5. Therefore we decided to use the robust standard errors by Newey-West which provide a consistent estimation of the covariance matrix in case of heteroscedasticity or autocorrelation of unknown form. The estimation results hardly altered.

In 2008 the immediate (−7.3%) and one month lagged (+8.3%) for KPM_GWB interventions are both significant, but have opposite effects and almost cancel each other out. As it seems unlikely to us that the immediate effect of an intervention is negative followed by a positive effect we decided to test whether the two effects cancel each other out. According to a Wald test the hypothesis that the sum of the immediate and one month lagged effect equals zero cannot be rejected (p = 0.78). Therefore we decided to remove the immediate and one month lagged effect for KBPM_GWB in 2008 from the set of explanatory variables.

We did some diagnostic checks on the residuals and it turned out that they were autocorrelated. Including AR(1) and AR(2) terms in the set of explanatory variables solved the problem.

We ran a Wald redundancy test in order to test the joint significance of the calendar effects (11 month dummies). The p-value (0.93) of the F-statistic indicated they were not. Therefore we removed them from the set of explanatory variables.

We examined whether interventions aimed at consumers led to higher debit card acceptance, using both immediate and lagged variables. These interventions did not have a significant impact on the number of installed debit card terminals.

Jonker (2011) finds that in 2007 many merchants were unaware of the costs associated with cash and card acceptance. 29% of retailers did not know their costs of cash and 38% did not know their costs of card payments.

References

Arango C, Huynh K and Sabetti L (2015) Consumer payment choice: merchant card acceptance versus pricing incentives. J Bank Financ 55:130–141

Aydogan, S (2016), Insights on Consumer Payment Behavior: What Factors Determine and Allow to Influence the Use of Payment Instruments?, PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Bagnall J, Bounie D, Hyunh K, Kosse A, Schmidt T, Schuh S and Stix H (2016) Consumer cash usage: A Cross-Country Comparison with Payment Diary Survey Data, Forthcoming in Int J Central Banking 12(4), 1–61

Bass FM and Leone RP (1983) Temporal aggregation, the data interval bias, and empirical estimation of bimonthly relations from annual data. Manag Sci 29(1):1–11

Berndt ER (1991) The practice of econometrics. Classic and contemporary. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading

Bolt W and Chakravorti B (2012) Digitisation of retail payments, in Feitz M, Waldfogel J (eds) The Oxford handbook of the digital economy, Oxford University Press, 108–137

Bolt W, Jonker N and Van Renselaar C (2010) Incentives at the counter: an empirical analysis of surcharging card payments and payment behavior in the Netherlands. J Bank Financ 34:1738–1744

Borzekowski R, Kiser E and Ahmed S (2008) Consumers use of debit cards: patterns, preferences, and price response. J Money Credit Bank 40:149–172

Bounie D, Van Hove L and François A (2016) Consumer payment preferences, network externalities, and merchant card acceptance: an empirical investigation, Review of Industrial Organization, forthcoming

Brits H, Winder C (2005), Payments are no free lunch, DNB occasional studies 3(2), De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam

Carbó-Valverde S and Liñares-Zegarra JM (2011) How effective our rewards programs in promoting payment card usage? Empirical Evidence. J Bank Financ 35:3275–3291

Ching AT and Hayashi F (2010) Payment card rewards programs and consumers payment choice. J Bank Financ 34:1773–1787

Clarke DG (1976) Econometric measurement of the duration of advertising effects on sales. J Mark Res 13(4):345–357

Cruijsen van der C. and Plooij, M. (2015), Changing payment patterns at point-of-sale: their drivers, DNB working paper 471, De Nederlandsche Bank

Cruijsen van der C., Hernandez, L. and Jonker, N. (2016), In love with the debit card, but still married to cash, Applied Economics, forthcoming

Danmarks Nationalbank (2012) Costs of payment in Denmark. Denmarks Nationalbank, Copenhagen

DNB/ DPA (2014) Factsheet Betalen aan de kassa 2013. De Nederlandsche Bank nv/ Dutch Payment Association, Amsterdam

Durkin S, Brennan E and Wakefield M (2012) Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control 21:127–138

Eschelbach M and Schmidt T (2013) Precautionary motives in short-term cash management: evidence from German POS interventions. Deutsche Bundesbank discussion paper 38/2013

Esteves P and Rodrigues P (2010) Calendar effects in daily ATMs withdrawals, working paper 2010–12, Banco de Portugal

Foundation for the Promotion of Efficiency in Payments (2009) Annual Report 2009

Foundation for the Promotion of Efficiency in Payments (2010) Annual Report 2010

Foundation for the Promotion of Efficiency in Payments (2011) Annual Report 2011

Foundation for the Promotion of Efficiency in Payments (2012) Annual Report 2012

Foundation for the Promotion of Efficiency in Payments (2013) Terugblik op het Vierjarenplan 2009-2012

Gresvik O and Haare H (2009), Costs in the Norwegian payment system, staff memo no. 4, Norges Bank

HBD (2009) HBD Monitor Betalingsverkeer 2009.

HBD (2011) HBD Monitor Betalingsverkeer 2011

Helmig B, Thaler J (2010) On the effectiveness of social marketing—what do we really know? J Nonprofit Publ Sec Marketing 22:264–287

Hernandez L, Jonker N and Kosse A (2017) Cash versus debit card: the role of budget control. J Consum Aff 51(1):91–112

Horst van der F and Matthijsen E (2013) The irrationality of payment behavior. Conclusions based on literature and direct observations in a virtual-reality and neuroscientific study, DNB occasional study 11(4). De Nederlandsche Bank n.v., Amsterdam

Jonker N (2007) Payment instruments as perceived by consumers - results from a household survey. De Economist 155:271–303

Jonker N (2011) Card acceptance and surcharging: the role of costs and competition. Rev Netw Econ 10(2):1–35

Jonker N (2013) Social costs of POS payments in the Netherlands 2002–2012: Efficiency gains from increased debit card usage, DNB Occasional study 11(2). De Nederlandsche Bank n.v., Amsterdam

Kosse A (2013) Do newspaper articles and card fraud affected debit card usage? J Bank Financ 37:5382–5391

Kosse A (2014) Consumer payment choices: Room for further digitization? Ph.D. thesis. Tilburg University, Tilburg

Loke YL (2007) Determinants of merchant participation in credit card payment schemes. Rev Netw Econ 6(4):1–21

Panteia (2013) The cost of point-of-sale transactions in 2012, Panteia report, Zoetermeer

Pauwels K (2004) How dynamic consumer response, competitor response, company support and company inertia shape long-term marketing effectiveness. Mark Sci 23(4):596–610

Schmalensee R (1972) The economics of advertising, Amsterdam: North Holland

Schmiedel H, Kostova G and Ruttenberg W (2013) The social and private costs of retail payment instruments: a European perspective. J Financ Mark Infrastructures 2:37–75

Segendorf B and Jansson T (2012) The cost of consumer payments in Sweden. Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper Series 262, Stockholm

Sethuraman R, Tellis GJ and Briesch R (2011) How well does advertising work? Generalizations from a Meta-Analysis of Brand Advertising Elasticity. J Mark Res 48:457–471

Shy O and Stavins J (2015) Merchant steering of consumer payment choice: evidence from a 2012 diary survey. J Behav Exp Econ 55:1–9

Simon J, Smith K and West T (2010) Price incentives and consumer payment behaviour. J Bank Financ 34:1759–1772

Strong EK (1925) Theories of selling. J Appl Psychol 9:75–86

Tellis GJ (2004) Effective advertising: understanding when, how and why advertising works. Sage Publications. University of South Carolina, Columbia

Toth J, van Vreden W and van Ossenbruggen R (2010) Toonbankbetalingen in Nederland: Segmentatieonderzoek 2010. Currence, Amsterdam

Triandis HC (1980) Values, attitudes, and interpersonal behavior. In: Howe HE Jr, Page M (eds) Nebraska symposium of motivation (Vol. 27, 195–259). University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln

Vakratsas D and Ambler T (1999) How advertising works: what do we really know? J Mark 63:26–43

Verdier M (2011) Interchange fees in payment cards systems: a review of the literature. J Econ Surv 25:273–297

Verma VK (1980) A price-theoretic approach to the specification and estimation of the sales-advertising function. J Bus 53(3):S115–S138

Wansink B and Ray ML (1996) Advertising strategies to increase usage frequency. J Mark 60:31–46

Wils J, Hoevenagel R and Van der Zeijden P (2012) Monitor betalingsverkeer 2009–2012. Panteia, Zoetermeer

Wood W and Quinn JM (2005) Habits and the structure of motivation in everyday life. In: Forgas JP, Williams KD, Hippel W (eds) Social motivation: conscious and unconscious processes, 55–70. Cambridge University Press, New York

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cornel van Mastrigt and Eric Sloothaak of the Dutch/German ACH Equens for kindly sharing their data on debit card transactions in the Netherlands, Miriam Osten and Renate de Vree from the Foundation for the Promotion of Efficient Payments and Helen van Houwelingen and Patricia Zwaan of the Dutch Payment Association for sharing information on the public campaign and their valuable comments on the results of this study. We are also indebted to Hao Zhou and Jeanne Spronck of Erasmus University Rotterdam for the valuable contribution they made during their internship, and want to thank the editors, two anonymous referees, the participants in the DNB lunch seminar and the DNB Payments conference 2016, in particular Hans Brits, Kim Huynh, David-Jan Jansen and Maarten van Rooij for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper and Gareth Budden, Renée Dekker and Jan de Vries for linguistic services. All remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1 Overview of all interventions

2007 | 2010 |

|---|---|

KBPM - large retail chains (GWB) | KBPM - Branches |

Tag-on AH | Liquor stores |

Logo tag-on Aldi/Intratuin/Action | Supermarkets |

Start KBPM: intervention with Estelle Gullit | Fashion |

Retailer | KBPM - GWB |

Payment information brochure | Blokker |

Consumer | Consumers |

KBPM - advertisements | Debit card week |

KBPM - promotion teams | Debit card user of the day |

New PIN POS available | |

2011 | |

KBPM - Branches | |

Garden centres and DIY stores | |

2008 | Petrol |

KBPM - Branches | Horeca |

Supermarket | UPTO |

KBPM - GWB | Debit card champions |

Tag-on AH | |

Tag-on McDonalds | 2012 |

Tag-on C1000 | UPTO |

Tag-on Primera/Kruitvat/Blokker | Food |

Retailers | Petrol and tobacco |

SME mailing: win your own commercial | Catering industry |

KBPM - radio campaign | Supermarkets |

Payment information brochure | All branches |

2009 | 2013 |

KBPM - Branches | PJG |

Supermarkets | Commercials |

Drugstores | RTL4 “Did you know?” |

Liquor stores | PJG - Branches |

DIY stores | Primera/ Telegraaf |

KBPM - GWB | Peijnenburg/ Dirk van den Broek |

Tag-on Bart Smit, Coop, Marskramer | |

V&D tag-on | Supermarkets |

Jumbo tag-on | |

Tag-on Hema, Xenox, Zeeman | |

AH tag-on | |

Consumers | |

PIN and WIN Winterparty | |

Retailers | |

Payment information brochure |

Appendix 2 Robustness check

Appendix 3 Timing of interventions

One possible reason for endogeneity between the timing of interventions and the influence of interventions on consumers’ payment behaviour could be that in some periods people are more liquidity constrained than in other periods. In the liquidity constrained periods, consumers spend less or may be more prone to use cash in order to reduce the risk of overspending, leading to fewer debit card transactions and making them less responsive to interventions. People may be more liquidity constrained just after the ‘expensive’ December month, or after the expensive ‘summer holiday season,’ which runs between July and August. Furthermore, within a month people may experience differences in the extent to which they can manage financially; e.g. many people are liquidity constrained in the third/fourth week of the month, just before they receive their salary, pension or social security benefit. On the other hand, there are also periods when the Dutch are less likely to have financial problems, like in the months April/May when they receive an additional payment of about 8% of their annual income, called ‘holiday money’ or at the end of the month when they have just received their salary/pension/social security benefit. We compared these liquidity constrained periods with the timing of the interventions by examining the differences in the incidence of intervention weeks within a month and between months for the period 2007–2013, see Table 6 below.

It turns out that there were hardly any interventions in January and February. During these months the campaign team was busy evaluating the impact of interventions in the previous year and making preparations for interventions in the current year. On the other hand, the post-summer holiday months of September and October have a relatively high incidence of weeks with interventions, Furthermore, within-month liquidity constraints did not seem to play a role in the timing of interventions, as the week of the month with the highest likelihood that consumers have financial difficulties (week 3) also has the highest incidence of interventions.

We estimated correlation coefficients between the extent in which a month/week in the month can be characterised as liquidity constrained (−1), neutral (0) or financially sound (+1) and the number of weeks with interventions to get a rough indication whether the campaign team considered the financial position of consumers when planning the interventions. It turns out that there is a weak positive correlation (+0.27) between the financial position measure and the incidence of interventions on a monthly basis, but a negative correlation (−0.52) on a ‘week in the month’ basis. Overall, we conclude that there is hardly any evidence that the financial position of Dutch households played a role in the timing of the interventions.

Appendix 4 VAR estimates and Granger Causality

We estimated a simple VAR model: A(L)Y m = BX m + ε m , with Ym the vector containing the endogenous variables d(log(DCm)), d(log(Terminalsm)), which reflects retailer demand; d(log(GT_pinpasm)), which reflects consumer demand; and d(log(Retail_salesm)), which reflects the value of retail sales as endogenous variables, the matrix A(L) being the matrix polynomial reflecting the lag operator of order 3, and Xm the vector containing a constant term and 11 dummies for the calendar months January to November as exogenous variables. Subsequently, we tested for Granger causality of the four endogenous variables, see Table 7

According to Granger Causality / Block Wald tests the hypothesis that d(log(DCm)) is exogenous cannot be accepted (p = 0.000), but the hypotheses that d(log(Terminalm)), d(log(Retail_salesm)) and d(log(GT_pinpasm)) are exogenous are accepted at the 5% level of significance. The corresponding p-values of the tests are p = 0.8945 for d(log(Terminalsm), p = 0.1830 for d(log(Retail_salesm)) and p = 0.4798 for d(log(GT_pinpasm)). These results indicate that of the four variables, only one can be considered as endogenously determined by the other three, but this does not hold for the other three variables; they are not interrelated with the other three “endogenous” variables.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jonker, N., Plooij, M. & Verburg, J. Did a Public Campaign Influence Debit Card Usage? Evidence from the Netherlands. J Financ Serv Res 52, 89–121 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-017-0281-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-017-0281-6