Abstract

This study examines family-level risk taking behavior from the perspective of the strategic choice of risk. We examine whether family-level risk taking tendency is affected by a fund family’s flow tournament position in the mutual fund industry. We use family-level excess fund flow, which is defined by the gap between the actual net flows and expected net flows of a fund family, to proxy for its interim fund-flow tournament position. A fund family is an interim winner (loser) if it experiences better (worse) than expected net flows. Two measures are used to proxy for risk taking strategy: (1) Active Share; and (2) the Standard Deviation of Fund Holdings at Family Level. Overall, we conclude that fund families classified as interim losers and top interim winners in a net flow tournament position exhibit risk taking propensities. Bottom dwellers increase risk for survival, whereas leaders increase risk to retain their leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Literature that examines strategies to increase cash flows to fund families includes Massa (2003), Nanda et al. (2004), Khorana et al. (2005), Gaspar et al. (2006), Guedj and Papastaikoudi (2008), Evans (2010), Chen and Lai (2010), Nohel et al. (2010), Cici et al. (2010), and Bhattacharya et al. (2013).

Here, we add one note related to the importance of Active Shares: Cremers and Petajisto (2009) document that approximately one-third of U.S. equity fund assets are managed by “closet indexers,” i.e., fund managers who should manage their investment portfolios actively but do not deviate enough from their market indexes to justify their fees. This measure has received considerable media coverage, and information services such as the Morningstar Fund Family Report have begun publishing Active Share information as a proxy for fund risk taking tendency.

See Heinkel and Stoughton (1994), Brown et al. (1996), Chevalier and Ellison (1997), Busse (2001), Elton et al. (2003), Qiu (2003), Goriaev et al. (2005), Kempf and Ruenzi (2008), Kempf et al. (2009), Chen and Pennacchi (2009), Basak and Makarov (2012), Schwarz (2012), Cullen et al. (2012), Basak and Makarov (2014).

Specifically, we include funds with the Wiesenberger Objective Codes G, I, GCI, IEQ, LTG, MCG, and SCG; funds with the Strategic Insight Investment Objective Codes AGG, GMC, GRI, GRO, ING, SCG, and SEC; and funds with the Lipper Objective and Classification Codes EI, EIEI, ELCC, G, GI, I, LCCE, LCGE, LCVE, LSE, MC, MCCE, MCGE, MCVE, MLCE, MLGE, MLVE, MR, SCCE, SCGE, SCVE, and SG.

Schwarz (2012) documents that mutual fund tournaments are subject to sorting bias, which is caused by the sorting of first-half risk levels when establishing relative midyear performance. He further demonstrates that the direction of the sorting bias changes depending on the market condition. The author suggests one way to overcome this bias is to use portfolio holdings’ data and calculates the equally-weighted average security standard deviation for each fund based on its midyear holdings. Following his method, to isolate the effect of market condition on fund-level risk taking measures, for the fund level we also calculate the equally-weighted average security standard deviation for each fund based on its prior-quarter holdings. We then calculate the Standard Deviation of Fund Holdings at Family Level as the value-weighted average standard deviation of member funds affiliated with a fund family using each fund’s total net assets as the weight.

Furthermore, for fund level we also calculate the value-weighted average security standard deviation for each fund using the share price provided in the portfolio holding database (i.e., Thomson Reuters Mutual Fund Holding database) and then calculate the Standard Deviation of Fund Holdings at Family Level as the value-weighted average standard deviation of member funds affiliated with a fund family.

We have constructed the empirical analysis based on both equally-weighted and value-weighted methodology, and both methods generate consistent results. We chose to present the equally-weighted results to isolate the effect of market condition on fund-level standard deviation and to include more observations (about 700 more observations are retained based on the equally-weighted method). The results based on value-weighted method are also available upon request.

In this study, we also use two univariate measures to proxy for the flow tournament position of a fund family in period t. In particular, fund families that experience higher relative net flow growth than their own relative return performance are considered interim winners in the fund-flow tournament. Relative Flow Dummy 1 is equal to one when the relative net flow growth of a fund family is higher than its own relative return performance over the previous 1-year period from (t-1) to t year; and 0 otherwise. Relative Flow Dummy 2 is equal to one when the relative net flow growth of a fund family is higher than its own relative return performance over the two-year period from (t-3) to (t-1) year; and 0 otherwise. According to our strategic choice of risk argument, we expect a negative relation between Relative Flow Dummies and family’s risk-taking tendency. Empirical results on Relative Dummies are consistent with our findings using Excess Flows. The detailed procedure used to calculate the variables and the results are reported in Appendix 1 (Tables 8 and 9).

\( {\alpha}_{f,t-1}^{\kern0.2em previous\kern0.2em 1\kern0.2em year\kern0.2em period}=\frac{{\displaystyle {\sum}_{j=1}^J}{\alpha}_{j,t-1}^{\kern0.2em previous\kern0.2em 1\kern0.2em year\kern0.2em period}*TN{A}_{j,t-1}\ }{{\displaystyle {\sum}_{j=1}^J}TN{A}_{j,t-1}\ } \) is defined as the four-factor adjusted return of fund family f over the previous one year period, which is calculated as the value-weighted average of four-factor adjusted returns of all member funds within family f using previous one year return at the end of quarter t-1. TNA j,t − 1 is the total net assets of fund j at the end of quarter t-1, and J is the total number of member funds in family f. Similarly, α previous (t − 3, t − 1)year period f,t − 1 is defined as the four-factor adjusted return of fund family f over the two year period from (t-3) to (t-1) year at the end of quarter t-1.

\( Net\ flow\ Growt{h}_{f,t}^{\kern0.2em previous\ 1\ year\ period}=\frac{{\displaystyle {\sum}_{j=1}^J} Cumulative\ Net\ flow\ Growt{h}_{j,t}^{\kern0.2em previous\ 1\ year\ period}*TN{A}_{j,t}}{{\displaystyle {\sum}_{j=1}^J}TN{A}_{j,t}} \) is defined as the net flow growth rate of fund family f over the previous one year period of time t, which is calculated as the value-weighted average of net flow growth rate of all member funds within a fund family f. In particular, TNA j,t is the total net assets of fund j at the end of quarter t, Cumulative Net flow Growth previous 1 year period j,t is the cumulative net flow growth rate of fund j over the previous one year period at the end of quarter t, and J is the total number of member funds in family f at the end of quarter t. Similarly, Net flow Growth previous (t − 3,t − 1)year period f,t is defined as the net flow growth rate of fund family f over the two year period from (t-3) to (t-1) year at the end of quarter t.

For brevity, we do not report the results, but the table is available upon request.

References

Anderson A, Cabral LMB (2007) Go for broke or play it safe? dynamic competition with choice of variance. RAND J Econ 38:593–609

Barber BM, Odean T, Zheng L (2005) Out of sight, out of mind: The effects of expenses on mutual fund flows. J Bus 78:2095–2120

Basak S, Makarov D (2012) Difference in interim performance and risk taking with short-sale constraints. J Financ Econ 103:377–392

Basak S, Makarov D (2014) Strategic asset allocation in money management. J Financ 69:179–217

Bhattacharya U, Lee J, Pool V (2013) Conflicting family values in mutual fund families. J Financ 68:173–200

Brown DP, Wu Y (2016) Mutual fund flows and cross‐fund learning within families. J Fin 71:383–424

Brown KC, Harlow W, Starks LT (1996) Of tournaments and temptations: an analysis of managerial incentives in the mutual-fund industry. J Financ 51:85–110

Busse J (2001) Another look at mutual fund tournaments. J Financ Quant Anal 36:53–73

Cabral LMB (2003) R&D competition when firms choose variance. J Econ Manag Strat 12:139–150

Carhart M (1997) On persistence in mutual fund performance. J Financ 52:57–82

Chen H, Lai C (2010) Reputation stretching in mutual fund starts. J Bank Financ 34:193–207

Chen H, Pennacchi G (2009) Does prior performance affect a mutual fund’s choice of risk? theory and further empirical evidence. J Financ Quant Anal 44:745–775

Chen J, Hong H, Huang M, Kubik J (2004) Does fund size erode mutual fund performance? role of liquidity and organization. Am Econ Rev 94:1276–1302

Chevalier J, Ellison G (1997) Risk taking by mutual funds as a response to incentives. J Polit Econ 105:1167–1200

Cici G, Gibson S, Moussawi R (2010) Mutual fund performance when parent firms simultaneously manage hedge funds. J Financ Intermed 19:169–187

Coval JD, Moskowitz TJ (1999) Home bias at home: local equity preference in domestic portfolios. J Financ 54:2045–2073

Coval JD, Moskowitz TJ (2001) The geography of investment: informed trading and asset prices. J Polit Econ 109:811–841

Cremers KJ, Petajisto A (2009) How active is your fund manager? a new measure that predicts performance. Rev Financ Stud 22:3329–3365

Cullen G, Gasbarro D, Monroe GS, Zumwalt JK (2012) Changes to mutual fund risk: intentional or mean reverting? J Bank Financ 36:112–120

Elton E, Gruber M, Blake C (2003) Incentive fees and mutual funds. J Financ 58:779–804

Elton EJ, Gruber MJ, Green TC (2007) The impact of mutual fund family membership on investor risk. J Financ Quant Anal 42:257–277

Evans R (2010) Mutual fund incubation. J Financ 65:1582–1611

Gaspar J-M, Massa M, Matos P (2006) Favoritism in mutual fund families: evidence on strategic cross-fund subsidization. J Financ 61:73–104

Goriaev A, Nijman TE, Werker BJM (2005) Yet another look at mutual fund tournaments. J Empirical Financ 12:127–137

Guedj I, Papastaikoudi J (2008) Can mutual fund families affect the performance of their funds? Working Paper, University of Texas at Austin

Heinkel R, Stoughton NM (1994) The dynamics of portfolio management contracts. Rev Financ Stud 7:351–387

Huang J, Wei K, Yan H (2007) Participation costs and the sensitivity of fund flows to past performance. J Financ 62:1273–1311

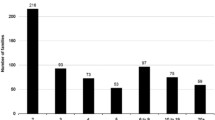

Investment Company Institute (2014) Fund complexes with positive net new cash flow to stock, bond, and hybrid funds (Figure 1.8), 2014 Investment Company Fact Book, available at https://www.ici.org/pdf/2014_factbook.pdf

Kempf A, Ruenzi S (2008) Tournaments in mutual fund families. Rev Financ Stud 21:1013–1036

Kempf A, Ruenzi S, Thiele T (2009) Employment risk, compensation incentives, and managerial risk taking: evidence from the mutual fund industry. J Financ Econ 92:92–108

Khorana A, Servaes H (2012) What drives market share in the mutual fund industry? Eur Finan Rev 16:81–113

Khorana A, Servaes H, Tufano P (2005) Explaining the size of the mutual fund industry around the world. J Financ Econ 78:145–185

Krasny Y (2011) Asset pricing with status risk. Quart J Fin 1:495–549

Lóránth G, Sciubba E (2006) Relative performance, risk and entry in the mutual fund industry. Topics Econ Anal Policy 6:1538–0653

Mamaysky H, Spiegel M (2002) A theory of mutual funds: optimal fund objectives and industry organization, Working Paper, Yale University

Massa M (2003) How do family strategies affect fund performance? when performance-maximization is not the only game in town. J Financ Econ 67:249–304

Nanda V, Wang ZJ, Zheng L (2004) Family values and the star phenomenon. Rev Financ Stud 17:677–698

Nohel T, Wang ZJ, Zheng L (2010) Side-by-side management of hedge funds and mutual funds. Rev Financ Stud 23:2342–2373

Pollet JM, Wilson M (2008) How does size affect mutual fund behavior? J Financ 63:2941–2969

Qiu J (2003) Termination risk, multiple managers and mutual fund tournaments. Europ Fin Rev 7:161–190

Schwarz CG (2012) Mutual fund tournaments: the sorting bias and new evidence. Rev Financ Stud 25:913–936

Siggelkow N (2003) Why focus? a study of intra-industry focus effects. J Ind Econ 51:121–150

Sirri E, Tufano P (1998) Costly search and mutual fund flows. J Financ 53:1589–1622

Taylor J (2003) Risk-taking behavior in mutual fund tournaments. J Econ Behav Org 50:373–383

Wahal S, Wang A (2011) Competition among mutual funds. J Financ Econ 99:40–59

Acknowledgments

Christine W. Lai (corresponding author) wishes to thank the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan for awarding a grant 103-2410-H-003 -031 -.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, CY., Lai, C.W. & Lee, LC. Strategic Choice of Risk: Evidence from Mutual Fund Families. J Financ Serv Res 51, 125–163 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-016-0242-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-016-0242-5