Abstract

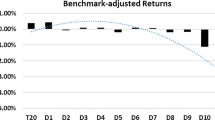

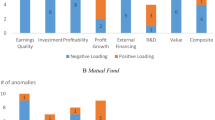

In this study, we collect a unique data set of Spanish domestic equity funds for the period 1999–2006 to test the existence of the well-known “smart money” effect. Our focus is to test whether superior performance follows fund flows, demonstrating investor skills, and whether the results are robust for aggregate portfolio analysis and for individual fund analysis. Empirical evidence shows that investor abilities reported by aggregate portfolio analysis are not very evident from a fund-level perspective. This study provides two major contributions to the literature: the separate consideration of purchases and redemptions, and the proposal of a “smart investor” effect which considers investor movements instead of traditional money flows. Results show that investors’ selling decisions are less smart than their buying decisions and that investors, as individuals, are not significantly smarter than money.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Mutual Fund Fact Book 2007. ICI (Investment Company Institute).

The Spanish mutual fund industry has experienced growing market share at the European level since the late 1990s. By the end of 2006, Spain managed 4.69% of the assets in the European UCITS industry (source: EFAMA, European Fund and Asset Management Association). The average number of funds in Keswani and Stolin (2008) is 461 per year in a sample of U.K. funds from 1992 to 2000. Nevertheless, note that the sample in the U.S.; for instance, in Zheng (1999) the number of funds in existence each month ranges from a minimum of 281 and a maximum of 1,196 in a sample from 1961 to 1993.

Zheng (1999) compares this general approach with the assumption of investment at the beginning of a quarter and finds robust results.

Following Carhart (1997), PR1YR is constructed as the equally weighted average of stocks traded in the Spanish stock market with the highest 25% 11-month returns lagged 1 month minus the equally weighted average of stocks with the lowest 25% 11-month returns lagged 1 month. These returns are adjusted for dividends, seasoned equity offerings, and splits.

This restriction, along with the fact that we do not take into account extreme cash inflow rates commonly observed during the first quarters due to inception bias, reduces the final number of funds included in the study to 112.

Test results are similar using 3-month holding period performance measures. They are not included for the sake of brevity but can be requested from the authors.

Shu et al. (2002) approximate small and large-amount investors and detect different patterns in buy and sell behavior in Taiwan equity funds.

As shown in Table 3, results for the different measures of performance are very similar. For the sake of brevity, only the excess return and the alpha of the four-factor model are reported.

Please notice that Eq. 6 includes investor timing and selection abilities together because the excess flow and excess performance is computed over the average of the category. A pure timing analysis should focus on whether an investor is able to select the best moment to invest in that fund over its performance. We discard that direction for two main reasons. First, it does not seem plausible that investor decisions are only based on time with “a priori” selection of the objective fund. And, second, even if an investor was able to anticipate the best performance of a certain fund, it would not mean that he or she is smart if this fund is significantly underperforming the average of its category.

For the sake of brevity, we only report the results of the 12-month holding period.

References

Baquero G, Verbeek M (2005) A portrait of hedge fund investors: flows, performance and smart money. European Financial Management Association 2005 Annual Meetings. Milan, Italy

Berk JB, Green RC (2004) Mutual fund flows and performance in rational markets. J Political Econ 112(6):1269–1295

Braverman O, Kandel S, Wohl A (2007) Aggregate mutual fund flows and subsequent market returns. AFA 2008 New Orleans Meetings Paper. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=795146

Carhart MM (1997) On persistence in mutual fund performance. J Finance 52(1):57–82

Chevalier J, Ellison G (1997) Risk taking by mutual funds as a response to incentives. J Political Econ 105(6):1167–1200

Fama EF, French KR (1993) Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. J Financ Econ 33(1):3–56

Ferruz L, Ortiz C, Sarto JL (2009) Decisions of domestic equity fund investors: determinants and search costs. App Financ Econ 19(16):1295–1304

Frazzini A, Lamont OA (2008) Dumb money: mutual fund flows and the cross-section of stock returns. J Financ Econ 88(2):299–322

Friesen GC, Sapp TRA (2007) Mutual fund flows and investor returns: an empirical examination of fund investor timing ability. J Bank Finance 31(9):2796–2816

Gruber MJ (1996) Another puzzle: The growth in actively managed mutual funds. J Finance 51(3):783–810

Guercio DD, Tkac PA (2002) The determinants of the flow of funds of managed portfolios: mutual funds vs. pension funds. J Financ Quant Anal 37(4):523–557

Ippolito RA (1992) Consumer reaction to measures of poor quality: evidence from the mutual fund industry. J Law Econ 35(1):45–70

Jegadeesh N, Titman S (1993) Returns to buying winners and selling losers: implications for stock market efficiency. J Finance 48(1):65–91

Ke D, Ng L, Wang Q (2005) Smart money? Evidence from the performance of mutual fund investors. Proceedings of Midwest Finance Association (MFA) 54th Annual Meeting

Keswani A, Stolin D (2008) Which money is smart? Mutual fund buys and sells of individual and institutional investors. J Finance 63(1):85–118

Newey WK, West KD (1987) A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica (1986–1998) 55(3):703–708

Sapp T, Tiwari A (2004) Does stock return momentum explain the "smart money" effect? J Finance 59(6):2605–2622

Shu P, Yeh Y, Yamada T (2002) The behavior of Taiwan mutual fund investors—performance and fund flows. Pac-Basin Finance J 10(5):583–600

Sirri ER, Tufano P (1998) Costly search and mutual fund flows. J Finance 53(5):1589–1622

Zheng L (1999) Is money smart? A study of mutual fund investors' fund selection ability. J Finance 54(3):901–933

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to David Musto (the editor) and an anonymous referee for their insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank José Luis Sarto, Manuel Armada and participants at the XVI Finance Forum of the Spanish Finance Association for helpful comments. The authors are also grateful to MSCI for providing index data. Any remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vicente, L., Ortiz, C. & Andreu, L. Is the Average Investor Smarter than the Average Euro?. J Financ Serv Res 40, 143–161 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0102-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0102-2