Abstract

Though the overall numbers of women judges remain small, higher proportions of women have been appointed to many lower courts in common law, and particularly in civil law, countries. This paper investigates whether the experiences of judging and judicial work differ among women and men magistrates in Australia’s lower courts. The particular focus is satisfaction with their work as judges. In so doing, it helps build up a picture of the extent of the gendered nature of the judiciary as an occupation. Measures of overall job satisfaction identify few gender differences; more refined measures highlight areas of divergence between men and women magistrates, suggesting gendered experiences of judicial work which result from particular characteristics of the occupation, as presently constituted, rather than the nature of judging itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Australia is a federal system, with national courts and a court system for each state operating separately. Commonwealth courts include the High Court, the Federal Court, the Family Court and the Federal Magistrates Court. Each Australian state and territory has a Supreme Court, and a Magistrates or Local Court (as it is called in New South Wales). There is also an intermediate trial court, the District or County Court, except in the smallest jurisdictions, Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory and Tasmania.

Until the late 1970s, in most Australian states and territories, the magistracy was part of the public service. Many magistrates were promoted into the position from clerks of court and may not have been qualified for or admitted to legal practice. When the magistracy was separated from the public service and given improved security of tenure and other protections for judicial independence, admission to practice became a necessary qualification for appointment (Mack and Roach Anleu 2004, 2006a). These changes were part of an overall increase in the professionalisation of the magistracy (Roach Anleu and Mack 2008). By the time of the survey, only about one-fifth of magistrates had held positions as clerks of court (Mack and Roach Anleu 2005). There were very few, if any, women magistrates during the period when the magistracy was part of the public service, because there were few or no women clerks. Interestingly, women have entered the magistracy at a time when the professional status of the magistracy has been enhanced. However, the interaction of these developments is beyond the scope of this article.

Because three-quarters of magistrates responding to the survey were male, reporting overall results will be shaped more by male than female responses, especially when they are different. As the number of female respondents was less than 100 (n = 44), where results are reported by gender, small percentage differences (less than 10 percentage points) cannot be regarded as demonstrating an observable difference.

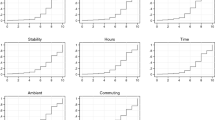

These charts were obtained by imposing numerical values on the level of satisfaction response categories and then averaging the sum of these responses for each of the facets of work. Satisfaction response categories and their imposed values were as follows: Very satisfied = 10, Satisfied = 5, Neutral = 0, Dissatisfied = −5, Very dissatisfied = −10. For example, taking the job facet ‘hours’, if three respondents were very satisfied and one was dissatisfied, this would give a value of 6.25 for ‘hours’ [(10 + 10 + 10 − 5)/4 = 6.25]. If two respondents were very satisfied and two were dissatisfied, this would give a value of 2.5 [(10 + 10 − 5 − 5)/4 = 2.5] and so on. This provides a measure of relative satisfaction for each facet of work. It also allows concise gender comparisons. Importantly, however, imposing values in this way can mask other findings. For example, if 100 respondents were very satisfied and 100 were very dissatisfied, this would give a value of 0. Because nearly all facets of work were rated positively, smaller positive values like ‘technical support’ could be argued to indicate relative dissatisfaction in comparison to a facet like ‘geographical location’ which had a much greater positive response (also see Hull and Harter 2005, p. 260).

Scores for the seven of the eight job clusters—nature of the work, autonomy, opportunities, remuneration, administration, convenience/lifestyle and resources—were obtained by calculating the mean responses for the individual job facets that constitute each cluster. For example, for nature of the work, each of the values—Very satisfied, Satisfied, Neutral, Dissatisfied, Very dissatisfied—was calculated by obtaining the mean for each of the values for the four facets: overall work, diversity of the work, content of work and intellectual challenge. Scores for each of the eight clusters and the single facets are reported in the text but not in a table.

References

Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration. 2008. Judges and magistrates (% of women). http://www.aija.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=32&Itemid=121. Accessed 13 June 2008.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2003. 6302.0 Average weekly earnings, Australia (November). http://www.abs.gov.au. Accessed 21 Apr 2004.

Baron, James N., and Jeffrey Pfeffer. 1994. The social psychology of organizations and inequality. Social Psychology Quarterly 57: 190–209.

Belleau, Marie-Claire, and Rebecca Johnson. 2008. Judging gender: Difference and dissent at the Supreme Court of Canada. International Journal of the Legal Profession 15: 57–71.

Bigoness, William J. 1988. Sex differences in job attribute preferences. Journal of Organizational Behavior 9: 139–147.

Brockman, Joan. 2001. Gender in the legal profession: Fitting or breaking the mould. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Chiu, Charlotte. 1998. Do professional women have lower job satisfaction than professional men? Lawyers as a case study. Sex Roles 38: 521–537.

Chiu, Charlotte, and Kevin T. Leicht. 1999. When does feminization increase equality? The case of lawyers. Law and Society Review 33: 557–593.

Crosby, Faye. 1982. Relative deprivation and working women. New York: Oxford University Press.

Darbyshire, Penny. 2006. Cameos from the world of district judges. Journal of Criminal Law 70: 443–457.

Dinovitzer, Ronit, and Bryant G. Garth. 2007. Lawyer satisfaction in the process of structuring legal careers. Law and Society Review 41: 1–50.

Dinovitzer, Ronit, Bryant G. Garth, Richard Sander, Joyce Sterling, and Gita Z. Wilder. 2004. After the JD: First results of a national study of legal careers. Chicago: NALP Foundation for Law Career Research and Education and the American Bar Foundation. http://www.nalpfoundation.org/webmodules/articles/articlefiles/87-After_JD_2004_web.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2008.

Epstein, Cynthia Fuchs. 1981. Women in law. New York: Basic Books.

Feenan, Dermot. 2005. Applications by women for silk and judicial office in Northern Ireland. A Report Commissioned by the Commissioner for Judicial Appointments for Northern Ireland. Jordanstown: School of Law, University of Ulster. http://cjani.courtsni.gov.uk/CJANIResearachReport.pdf. Accessed at 10 Nov 2008.

Feenan, Dermot. 2007. Understanding disadvantage partly through an epistemology of ignorance. Social and Legal Studies 16: 509–531.

Firebaugh, Glenn, and Brian Harley. 1995. Trends in job satisfaction in the United States by race, gender and type of occupation. Research in the Sociology of Work 5: 87–104.

Genn, Hazel. 1999. Paths to justice: What people do and think about going to law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Hagan, John, and Fiona Kay. 1995. Gender in practice: A study of lawyers’ lives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hagan, John, and Fiona Kay. 2007. Even lawyers get the blues: Gender, depression and job satisfaction in legal practice. Law and Society Review 41: 51–78.

Heinz, John P., Robert L. Nelson, Rebecca L. Sandefur, and Edward O. Laumann (eds.). 2005. Urban lawyers: The new social structure of the bar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hochschild, Arlie. 1989. The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking.

Hodson, Randy. 1989. Gender differences in job satisfaction. Why aren’t women more dissatisfied? The Sociological Quarterly 30: 385–399.

Hull, Kathleen E. 1999. The paradox of the contented female lawyer. Law and Society Review 33: 687–702.

Hull, Kathleen E., and Ava A. Harter. 2005. A satisfying profession? In Urban lawyers: The new social structure of the bar, ed. John P. Heinz, Robert L. Nelson, Rebecca L. Sandefur, and Edward O. Laumann, 256–274. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hunter, Rosemary. 2002. Talking up equality: Women barristers and the denial of discrimination. Feminist Legal Studies 10: 113–130.

Hunter, Rosemary. 2004. Fear and loathing in the sunshine state. Australian Feminist Studies 19: 145–157.

Hunter, Rosemary. 2005. Discrimination against women barristers: Evidence from a study of court appearances and briefing practices. International Journal of the Legal Profession 12: 13–49.

Kalleberg, Arne. 1977. Work values and job rewards: A theory of job satisfaction. American Sociological Review 42: 124–143.

Kenney, Sally J. 2002. Counting women judges: The intersection of law and politics. In Critical junctures in women’s economic lives: A collection of symposium papers, 118–128. St Paul: Center for Economic Progress, University of Minnesota.

Kenney, Sally J. 2004. Equal employment opportunity and representation: Extending the frame to courts. Social Politics 11: 86–116.

Kenney, Sally J. 2008. Thinking about gender and judging. International Journal of the Legal Profession 15: 87–110.

Kohen, Beatriz. 2008. Family judges in the city of Buenos Aires: A view from within. International Journal of the Legal Profession 15: 111–122.

Laster, Kathy, and Roger Douglas. 1995. Feminized justice: The impact of women decision makers in the lower courts in Australia. Justice Quarterly 12: 177–205.

Leiper, Jean McKenzie. 2006. Bar codes: Women in the legal profession. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Lempert, Richard O., David L. Chambers, and Terry K. Adams. 2000. Michigan’s minority graduates in practice: The river runs through law school. Law and Social Inquiry 25: 395–505.

Loscocco, Karyn A. 1990. Reactions to blue-collar work: A comparison of women and men. Work and Occupations 17: 152–177.

Lowndes, John. 2000. The Australian magistracy: From justices of the peace to judges and beyond: Part I. Australian Law Journal 74: 509–532.

Mack, Kathy, and Sharyn Roach Anleu. 2004. The administrative authority of chief judicial officers in Australia. Newcastle Law Review 8: 1–22.

Mack, Kathy, and Sharyn Roach Anleu. 2005. Educational and career background of magistrates: A preliminary report (Report No. 2/05). Adelaide: Magistrates Research Project, Flinders University.

Mack, Kathy, and Sharyn Roach Anleu. 2006a. The security of tenure of Australian magistrates. Melbourne University Law Review 30: 370–398.

Mack, Kathy, and Sharyn Roach Anleu. 2006b. Who are the magistrates? Demographic and social characteristics (Report No. 3/06). Adelaide: Magistrates Research Project, Flinders University.

Mack, Kathy, and Sharyn Roach Anleu. 2007. ‘Getting through the list’: Judgecraft and legitimacy in the lower courts. Social and Legal Studies 16: 341–361.

Malleson, Kate. 2003. Justifying gender equality on the bench: Why difference won’t do. Feminist Legal Studies 11: 1–24.

Malleson, Kate. 2006. Rethinking the merit principle in merit selection. Journal of Law and Society 33: 126–140.

Martin, Bill, and Jocelyn Pixley. 2005. How do Australians feel about their work? In Australian social attitudes: The first report, ed. Shaun Wilson, Gabrielle Meagher, Rachel Gibson, David Denemark, and Mark Western, 42–61. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Martin, Patricia Yancey, John R. Reynolds, and Shelley Keith. 2002. Gender bias and feminist consciousness among judges and attorneys: A standpoint theory analysis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27: 665–701.

Naffine, Ngaire. 1990. Law and the sexes: Explorations in feminist jurisprudence. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Rackley, Erika. 2002. Representations of the (woman) judge: Hercules, the little mermaid, and the vain and naked emperor. Legal Studies 22: 602–624.

Rackley, Erika. 2006. Difference in the House of Lords. Social and Legal Studies 15: 163–185.

Rackley, Erika. 2008. What a difference difference makes: Gendered harms and judicial diversity. International Journal of the Legal Profession 15: 37–56.

Roach Anleu, Sharyn. 1992. Critiquing the law: Themes and dilemmas in Anglo-American feminist legal theory. Journal of Law and Society 19: 423–440.

Roach Anleu, Sharyn, and Kathy Mack. 2006. Household, family and community activities (Report No. 6/06). Adelaide: Magistrates Research Project, Flinders University.

Roach Anleu, Sharyn, and Kathy Mack. 2007. Magistrates, magistrates courts and social change. Law and Policy 29: 183–209.

Roach Anleu, Sharyn, and Kathy Mack. 2008. The professionalization of Australian magistrates: Autonomy, credentials and prestige. Journal of Sociology 44: 185–203.

Rose, Michael. 2003. Good deal, bad deal? Job satisfaction in occupations. Work, Employment and Society 7: 503–530.

Ryan, John Paul, Allan Ashman, Bruce D. Sales, and Sandra Shane-DuBow. 1980. American trial judges: Their work styles and performance. New York: Free Press.

Schultz, Ulrike, and Gisela Shaw (eds.). 2003. Women in the world’s legal professions. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Schultz, Ulrike, and Gisela Shaw. 2008. Editorial: Gender and judging. International Journal of the Legal Profession 15: 1–5.

Seron, Carol, and Kerry Ferris. 1995. Negotiating professionalism: The gendered social capital of flexible time. Work and Occupations 22: 22–47.

Smith, Michael David. 1983. Race versus robe: The dilemma of black judges. New York: National University Publications.

Sommerlad, Hilary. 2002. Women solicitors in a fractured profession: Intersections of gender and professionalism in England and Wales. International Journal of the Legal Profession 9: 213–234.

Sommerlad, Hilary, and Peter Sanderson. 1998. Gender, choice and commitment: Women solicitors in England and Wales and the struggle for equal status. Dartmouth: Ashgate.

Thornton, Margaret. 1996. Dissonance and distrust: Women in the legal profession. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Thornton, Margaret. 2007. ‘Otherness’ on the bench: How merit is gendered. Sydney Law Review 29: 391–413.

Webley, Lisa, and Liz Duff. 2007. Women solicitors as a barometer for problems within the legal profession—time to put values before profits? Journal of Law and Society 34: 374–402.

Wilson, Bertha. 1990. Will women judges really make a difference? Osgoode Law Journal 28: 507–522.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded initially by a University-Industry Research Collaborative Grant in 2001 with Flinders University and the Association of Australian Magistrates (AAM) as the partners and also received financial support from the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration. It was funded by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project Grant (LP210306), 2002–2005, with AAM and all Chief Magistrates and their courts as industry partners and with support from Flinders University as the host institution. It is currently funded by an ARC Discovery Grant (DP0665198), 2006–2009. Thanks to Russell Brewer, Carolyn Corkindale, Elizabeth Edwards, Ruth Harris, Julie Henderson, Leigh Kennedy, Lisa Kennedy, Lilian Jacobs, Mary McKenna, Wendy Reimens, Rose Williams and David Wootton for research and administrative assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roach Anleu, S., Mack, K. Gender, Judging and Job Satisfaction. Fem Leg Stud 17, 79–99 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-009-9111-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-009-9111-z