Abstract

This study investigates the mechanisms driving the effectiveness of free-form communication in promoting cooperation within a sequential social dilemma game. We hypothesize that the self-constructing nature of free-form communication enhances the sincerity of messages and increases the disutility of dishonoring promises. Our experimental results demonstrate that free-form messages outperform both restricted promises and treatments where subjects select and use previously constructed free-form messages. Interestingly, we find that selected free-form messages and restricted promises achieve similar levels of cooperation. We observe that free-form messages with higher sincerity increase the likelihood of high-price and high-quality choices, thereby promoting cooperation. These messages frequently include promises and honesty, while threats do not promote cooperation. Our findings emphasize the crucial role of the self-constructed nature of free-form messages in promoting cooperation, exceeding the impact of message content compared to restricted communication protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Communication plays a pivotal role in human interactions, especially those requiring cooperation between individuals. Both economists and psychologists have a long-standing interest in the impact of free-form communication on decision-making. Economists tend to adopt a generalized and abstract approach, using comparisons of communication protocols to quantify the effect of communication and focusing on the resulting changes in outcomes (e.g., Bornstein & Rapoport 1988; Bochet et al. 2006; Charness & Dufwenberg 2006; Cooper and Kühn 2014). In contrast, the psychology literature includes remarkable works that explore the intricate nuances of language and meaning, especially with respect to the conveyance of probabilistic information (e.g., Budescu & Wallsten 1985; 1995; Wallsten et al. 1986; 1993), uncertainties (Budescu et al., 1988; von Furstenberg & Wallsten, 1990), and fuzzy reasoning (Zwick et al., 1987).

This study aims to deepen our comprehension of the effectiveness of natural language communication in fostering cooperation by drawing inspiration from both of these perspectives. We share with other scholars a curiosity about the nuances of communication while focusing on generality in our approach. In line with the rationales proposed by Ellingsen and Johannesson (2004) and Vanberg (2008), which are respectively based on lying aversion and guilt aversion, we propose a novel framework to explain why free-form communication may be even more effective than restricted promises. We hypothesize that individuals display more sincerity when constructing messages using their own words, which increases the disutility associated with disappointing others and thereby reinforces the effectiveness of free-form communication in fostering cooperation. Our hypothesis resonates with findings in psychology, which suggest that people are more inclined to engage in socially desirable actions when their sense of self is involved, as indicated by research from Bryan et al. (2011, 2013) and Chou (2015).

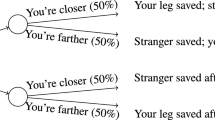

To test this idea, we conducted a sequential social dilemma game where buyers set prices for their goods and sellers determine the quality of the goods. We introduced five treatments: a baseline without communication, restricted promises, restricted threats, free-form communication, and a message-select treatment where messages are chosen from pre-constructed free-form options. In all communication treatments, the seller can send a costless, nonbinding message to the buyer before the dilemma begins.

This design allows us to explore factors that contribute to the differing effectiveness of free-form and restricted messages. We consider two plausible explanations. First, the richness of natural language may enhance the effectiveness of free-form communication. If this is the case, the message-select treatment should surpass the restricted promise treatment in effectiveness. Alternatively, the inherent sincerity of self-constructed free-form messages might be the key, regardless of message content. If this holds true, the free-form message treatment should outperform both the message-select and restricted promise treatments.

Our experimental findings indicate that free-form communication significantly outperforms all restricted communication treatments in terms of promoting cooperation. The message-select treatment performs as effectively as the restricted promise treatment but falls significantly short of free-form communication, highlighting the crucial role of self-constructed messages. In both the message-select and free-form treatments, we frequently observed the inclusion of promise and honesty notions. Interestingly, these notions appear more effective in promoting cooperation when they are part of free-form messages. Additionally, our analysis reveals that the restricted promise treatment is more conducive to cooperation compared to the restricted threat treatment. A notable aspect of these findings is the persistence of treatment differences in cooperative behavior, as evident from both the senders and receivers of messages. This suggests that both parties are aware of the varying levels of sincerity associated with different communication forms and their potential impact on cooperative outcomes. With additional evaluation sessions that rated the sincerity of the messages, we observed that messages with higher sincerity increase the likelihood of both high-price and high-quality choices, thereby promoting cooperation.

As emphasized by Rubinstein (2000),Footnote 1 “Economic theory is an attempt to explain regularities in human interaction, and the most fundamental nonphysical regularity in human interaction is natural language.” Economists strive to simplify human interaction as a structured decision-making process. However, real-life interactions, especially those in daily conversations, predominantly use natural language and thus introduce numerous complexities that are difficult to represent effectively within simplified economic models.

Consistent with the methodology of Rapoport and coauthors (e.g., Kahan & Rapoport, 1984; Rapoport, 2012), this study combines game-theoretical models with experimental research to understand decision-making processes in the context of natural language complexity. We use meticulously designed experiments to enhance our understanding of the effectiveness of natural language communication in promoting cooperation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the relevant studies on communication. Section 3 outlines our experimental design, and Sect. 4 presents the behavioral model and hypotheses. Section 5 presents the main findings, and Sect. 6 concludes the paper.

2 Related literature

2.1 Cheap talk

In the communication literature, pre-play “cheap talk” (i.e., non-binding, non-verifiable communication) is repeatedly shown to outperform many other mechanisms in resolving coordination or cooperation failures (e.g., Brandts & Cooper 2007; Duffy & Feltovich 2002). In a large-scale meta-analysis of 130 distinct experiments from 37 studies, Sally (1995) finds that communication is the most effective mechanism for solving social dilemmas such as the public goods game and the prisoner’s dilemma.

Economists are greatly interested in a theoretical understanding of the potential importance of cheap talk. Early studies in this area focus on whether pre-play communication can facilitate equilibrium play. For instance, Farrell (1987) discusses how cheap talk can foster asymmetric coordination in an entry game and offers the following logic: if players’ announced plans constitute a Nash equilibrium, then this equilibrium would become focal and be followed by both players, thus reducing the frequency of ex-post disequilibria. Rabin (1994) extends the analysis of Farrell (1987) to unlimited rounds of communication. In his model, the players make repeated, simultaneous statements about their intended actions before playing a coordination game; if this communication between players is sufficiently long, each player should perform at least slightly better than her worst Pareto-efficient Nash equilibrium.

The analyses by Farrell (1987) and Rabin (1994) provide a useful benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness of cheap talk. Their arguments are supported by several follow-up experimental studies in which cheap talk is shown to increase both the incidence of equilibrium play and the frequency of efficient equilibria. For example, Cooper et al. (1989) investigate the effect of communication in the Battle of the Sexes game. They find that communication significantly increases the frequency of equilibrium play, as the players can indicate their planned actions using cheap talk messages. Duffy and Feltovich (2002) find that one-way cheap talk results in increased coordination via a pure Nash equilibrium and thus increases efficiency. Blume and Ortmann (2007) study minimum and median games with Pareto-ranked equilibria in which multiple players can send numerical messages to signal their intended choices. Their results show that cheap talk increases coordination with a Pareto-efficient equilibrium.

However, no consensus exists regarding the effectiveness of pre-play communication for achieving efficient outcomes. Aumann (1990) expresses doubt that cheap talk can enhance trust and promote efficiency in a stag hunt game, given that the intention to cooperate during a hunt is self-serving: each player strictly prefers to tell others to cooperate, regardless of her own intention. However, Charness (2000) shows experimentally that even self-serving cheap talk can facilitate coordination to achieve an efficient equilibrium, provided that the signaling stage precedes the action stage.

Increasingly, studies are exploring why cheap talk increases the efficiency of outcomes. Conventionally, scholars invoke behavioral heuristics to explain the effectiveness of communication. For example, Ellingsen and Johannesson (2004) argue that people’s concerns about fairness and consistency drive them to follow through on their commitments. Charness and Dufwenberg (2006) offer a similar perspective, positing that players are guilt-averse and thus wish to avoid failing to fulfil their commitments to others. Vanberg (2008) revisits the game of Charness and Dufwenberg (2006) and proposes that the result is driven not by guilt aversion but rather by an intrinsic preference for promise-keeping. Lying aversion, defined as a person’s intrinsic motivation to maintain the credibility of their communications, is another common behavioral explanation for the effectiveness of cheap talk (Charness & Dufwenberg, 2010; Ellingsen & Östling, 2010; Lundquist et al., 2009). Fehrler et al. (2020) find that while promises increase transfers between subjects, the credibility of a statement crucially depends on participants’ self-selection into cheap-talk situations.

2.2 Comparison of communication protocols

The economics literature compares various channels and structures of communication to determine the effectiveness of different communication protocols (see, e.g., Brandts et al., 2019). Experimental evidence suggests that these protocols vary in terms of effectiveness. For example, Bochet et al. (2006) find that efficiency in a public goods game increases markedly with communication via a chat room but does not increase with numerical communication via computer terminals. Similarly, in a collective resistance game, Cason and Mui (2015) observe a higher level of coordination when rich communication is used than when simultaneous intention signals are used. Ben-Ner et al. (2011) compare two types of communication in a trust game: a single-round exchange of numerical proposals by a trustor and trustee, and a combination of proposal exchanges and unrestricted free chats. The authors find that although both kinds of communication facilitate trust and trustworthiness, verbal communication has a stronger effect than numerical signals. Charness and Dufwenberg (2006, 2010) find that written free-form promises increase trust and trustworthiness significantly in a one-shot trust game with hidden actions. In contrast, the use of a pre-designed “bare promise” message (for example, “I promise to choose ‘Roll’ ”) only moderately enhances trustworthiness. Lundquist et al. (2009) provide evidence that free-form messages lead to fewer lies than do pre-formulated promises in a hiring game with one-sided information asymmetry. In their experiment, the participants first perform a real-effort task to determine their skill, which is private information. They are then matched and play a one-shot game in which the applicant first signals her ability and the employer decides whether to offer a contract. The authors find that the proportion of low-skill applicants who over-report their abilities is significantly higher under the treatment with pre-formulated messages than under the treatment with free-form messages. Cooper and Kühn (2014) investigate how various communication types may foster cooperation in a two-stage collusion game. They find free-form chat to be the most effective communication method, especially when threats are involved. Moreover, they find that communication via a limited message space is not a good substitute for natural conversation.

2.3 What makes free-form communication more effective?

Ample evidence supports the superior efficacy of free-form communication compared with restricted messages, prompting researchers to investigate the underlying mechanisms of this efficacy. Experimental studies conducted across different environments offer explanations centering around distinct factors.

A group of existing research highlights the relationship-building function of free-form communication. A notable example comes from Mohlin and Johannesson (2008), where researchers attempted to explain the increased donation amounts in a standard dictator game when the recipient sends free-form messages. They designed a third-party communication treatment to isolate the content effect of free-form messages while eliminating the relationship-building effect. The authors find that the contributions from the relationship effects are comparable to the content effect in facilitating effective communication. In a study by Coffman and Niehaus (2020), the focus is on a sales setting where sellers engage in free-form conversation to persuade buyers to increase their valuations of objects. They examine two pathways of persuasion: appealing to the buyer’s self-interest and building rapport. The results show that sellers more frequently target buyers’ self-interest, and changes in self-interest explain a significant portion of persuasion. However, sellers are found to be most persuasive when they focus on rapport building.

The ability of free-form messages to facilitate type detection has also been extensively discussed in previous studies. In He et al. (2017), the authors explore the factors influencing the effectiveness of face-to-face communication in resolving social dilemmas. They tested several possible channels, and type detection is identified as playing a key role in increasing cooperation. The research also emphasizes the freedom to create promises in communication, as it not only enhances the commitment value but also aids in revealing the type. In a study by Ismayilov and Potters (2016), the aim is to understand whether promise-making (internal consistency) or promise-receiving (social obligation) can explain the effect of promises on trustworthiness. The results of that study indicate that promises do not directly induce trustworthiness; rather, promises are important in signaling types, being more likely to be made by cooperators than non-cooperators. Turmunkh et al. (2019) investigate the credibility of nonbinding pre-play statements about cooperative behavior using data from a high-stakes TV game show. To better understand the messages, they propose a two-by-two typology focusing on the conditionality and implicitness. The assumption of lying aversion is introduced, where potential defectors prefer statements that can be interpreted later as true. The authors’ analysis shows a link between statements with conditionality or implicitness and a reduced likelihood of cooperation, suggesting that malleability is a reliable criterion to differentiate types.

Additionally, there is a small but growing literature using the richness of free-form messages as an explanation for the effectiveness of free-form communication. Dugar and Shahriar (2018) conduct stag hunt games to understand the efficiency-enhancing capacities of various types of messages. While intentional signaling messages fail to facilitate cooperation, the ineffectiveness of such messages can be ameliorated by adding reason-based components. Notably, the reason-based messages are found to be an effective efficiency-enhancing device similar to free-form messages. Therefore, Dugar and Shahriar (2018) posit that the effectiveness of free-form communication can be explained by the sender’s ability to specify the reason for choosing the cooperative behavior. Wang and Houser (2019) use a pure coordination game to examine differences in effectiveness between communication via intention signaling and communication via natural language. Free-form messages in this environment are found to include both signaled intentions and attitudes (i.e., the strength of a message sender’s desire to have her message followed), and people respond to both intentions and attitudes when making decisions. The study finds that the difference in attitudes improves coordination significantly as the player indicating a weaker intention yields to the player indicating a stronger intention.

The psychology literature suggests that people are more inclined to engage in socially desirable behavior when their sense of self is evoked. This concept is rooted in the understanding that individuals often strive to maintain a positive self-image and are thus influenced by how their actions align with their personal identity. For example, Bryan et al. (2013) provided participants with an opportunity to claim unearned money at the experimenters’ expense, using instructions that highlighted the identity implications of cheating (e.g., “Please don’t be a cheater”) versus focusing on the action (e.g., “Please don’t cheat”). The study found that participants in the “cheating” condition claimed more money than those in the “cheater” condition, a pattern evident in both face-to-face and online settings. This outcome suggests the power of language in influencing ethical behavior by appealing to individuals’ desire to maintain a positive self-image. Similarly, Bryan et al. (2011) examined the impact of framing survey items to reflect a personal identity (e.g., “being a voter”) versus merely describing a behavior (e.g., “voting”). This study revealed that identity-based framing significantly increased voter registration and turnout, as evidenced by state records. These results highlight the role of self-concept management in motivating socially desirable actions. Chou (2015) investigated the effectiveness of various electronic signatures in comparison to handwritten signatures in deterring dishonesty. The study’s findings across seven experiments consistently showed that electronic signatures are less effective in curbing dishonest behavior. This ineffectiveness is linked to their inability to evoke a sense of self-presence in the signer. Meta-analyses further established the reliability of these associations, emphasizing the role of self-presence in ethical decision-making. These studies collectively show that when the self identity is evoked, individuals are more likely to behave in ways that are congruent with their values and societal norms. This tendency to act in a manner that preserves a positive self-concept can significantly shape behavior, particularly in contexts where ethical or moral decisions are involved.

The focus of our work is closely related to the last two strands of literature. To understand the difference in effectiveness between free-form messages and restricted messages, we consider both the role played by the richness of natural language and the self-constructed nature of the messages.

3 Experimental design

3.1 Sequential social dilemma

We design a sequential social dilemma game involving two players: a seller and a buyer. In the game, the buyer takes initiative and offers a price, which can be either high (\(P_H\)) or low (\({P_L}\)). Based on this offer, the seller then decides whether to provide a high-quality (\({Q_H}\)) or low-quality (\({Q_L}\)) product.

Both the buyer’s evaluation of the product, denoted as V(Q), and the production cost, denoted as C(Q), increase with the quality of the product. Specifically, higher-quality products are of higher value to the buyer and impose higher production costs on the seller. To introduce a social dilemma element, we carefully selected the following set of parameters for our experiment: \({V(Q_H)} = 300, V(Q_L) = 100; \ P_H = 200, P_L = 50; \ C(Q_H) = 100, C(Q_L) = 0\).

In the game, the buyer’s payoff is calculated as the difference between the value of the product and the price offered, while the seller’s payoff is derived from the difference between the price and the production cost.

Figure 1 presents the game tree, wherein a unique subgame perfect Nash equilibrium is achieved when the buyer proposes a low price and the seller, in response, provides a low-quality product. However, an opportunity for Pareto improvement exists if the buyer decides to offer a high price and, as a result, receives a high-quality product. This framework allows the examination of communication dynamics and their impact with respect to enhancing outcomes between the buyer and the seller across different treatments.

3.2 Communication treatments

Under the baseline treatment, the sequential social dilemma is conducted without any communication between the buyer and the seller. To compare the effects of free-form messages with those of restricted protocols, we introduce different communication treatments. Under these treatments, the seller is allowed to send a free, non-binding message to the buyer before the dilemma game begins. For this experiment, we designed four communication treatments that vary in terms of the form of the messages exchanged between the buyer and the seller.

Beginning with restricted messages, the restricted promise treatment allows the seller to choose between sending a restricted form of a promise, stating “If you pay a high price, I will choose high quality,” or leaving the message blank. Under the restricted threat treatment, the seller can choose to send a restricted form of a threat, stating “If you pay a low price, I will choose low quality,” or leaving the message blank.

Under the free-form communication treatment, the seller has complete freedom to write messages without any constraints on the number of words or message length.

Under the message-select treatment, the sender can choose from a list of 10 randomly selected messages crafted by sellers during the free-form communication treatment sessions, or leaving the message blank. Here, the richness of language in the message space (as analyzed in Sect. 5.4) is similar to that used under the free-form treatment, but the factor of message self-construction by the sender is removed. This allows us to isolate the effects of self-construction and message content richness that contribute to the differences in persuasiveness between restricted and free-form messages.

In all four communication treatments, we ensured that buyers were fully informed about the nature of the messages, whether they were selected from a pool or constructed by the sellers themselves. Under the two treatments with restricted messages, the buyer is fully informed about the messages available to the seller. Under the free-form treatment, the buyer is aware that the seller is free to write anything. Under the message-select treatment, the buyer is aware that the seller’s messages are chosen from a set of previously constructed options. However, the buyer is not provided with the explicit set of messages available to the seller. For the message-select treatment, the available message options were limited to a pool collected from the free-form treatment. To balance variety with manageability, we provided a list of 10 randomly selected messages, aiming to avoid overwhelming subjects with an excessive number of choices. This approach, however, may have introduced potential bias, as subjects might not have found messages that precisely matched their intended communication. Nevertheless, this limitation is further discussed in the results section, where we compare the content delivered in free-form and message-select treatments, and their effectiveness.

By comparing the differences between treatments, we can also effectively study the prevalence of cooperation failure under the baseline treatment and replicate previous findings that free-form messages tend to better promote cooperation than do restricted messages. Furthermore, this design enables us to deepen our insights into the dynamics of free-form and restricted communications and their respective impacts on cooperation outcomes.

3.3 Experimental details

The experiment took place at the Smith Experimental Economics Research Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, in November and December 2019 and November 2020.Footnote 2 The z-Tree program was used to conduct the experiment. Details regarding the numbers of sessions and participants per treatment can be found in Table 1. Overall, the experiment involved 354 participants, none of whom had prior experience with similar studies.

We adopted a between-subject design wherein each subject experienced only one treatment. Before experiencing the treatment, the subjects were provided with printed instructions. To ensure better comprehension, a recording of the instructions was played aloud. The detailed instructions can be found in Appendix 3.

Under each treatment, the game was played repeatedly for 10 rounds. We used stranger matching to pair the subjects and assigned their roles randomly. Under the message-select treatment, the list of messages was re-selected randomly during each round and varied across the sessions.

To ensure a non-negative payoff, both the seller and the buyer were provided with 100 tokens at the beginning of each round. After each round, the players were informed of their counterpart’s actions and earnings during that round. To prevent the players from hedging their bets across different rounds, payments were made only during one randomly selected round (for more details, see the discussion in Azrieli et al., 2018).

Upon the conclusion of the experiment, we collected additional information from the subjects, including their demographics and risk preferences, which were assessed using the method proposed by Crosetto and Filippin (2013). In addition, we examined their social preferences as part of the data collection process.Footnote 3

The experimental sessions lasted approximately one hour on average. The subjects’ average accumulated earnings were 56.18 RMB. This amount includes a 15 RMB show-up fee. The U.S. dollar/Chinese yuan (RMB) exchange rate during the experiment ranged from approximately 6.54 to 7.07.

4 Theoretical framework and hypotheses

To offer predictions and rationale for the effect of communication in our experiment, we present a straightforward theoretical framework. In this framework, we introduce the concept of \({ sincerity}\) as denoted by S, which reflects the perceived persuasiveness of a statement. Both the seller and the buyer are assumed to share a transitive ordering for \({ sincerity}\). For simplicity, we let \(S\in \{0,1,2,\ldots ,N\}\), with larger values in the set indicating higher degrees of \({ sincerity}\).

4.1 The seller’s problem

We assume that the seller incorporates both material interest and psychological costs into his utility function:

where \(\psi (P,Q)= {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1&{} if \ P=P_H\ and\ Q=Q_L\\ 0&{} otherwise \end{array}\right. }\), \(\chi (S,Q)= {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1&{} if \ S>0\ and\ Q=Q_L \\ 0&{} otherwise \end{array}\right. }\)

There are two psychological forces at play in this context. The first force, guilt aversion, is represented quantitatively as \({\theta \cdot S \cdot \psi (P,Q)}\). Here, \({\psi (P,Q)}\) is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 if the sender fails to meet the buyer’s expectations, and 0 otherwise. In the game, this occurs when the buyer offers a high price but receives a low-quality product, leading the seller to experience a disutility level of \(\theta \cdot S\). The parameter \(\theta\) reflects the seller’s sensitivity toward guilt and can take one of two values: \(\theta _H\) or \(\theta _L\), where \(\theta _H\) is greater than \(\theta _L\). Both players share a common prior, denoted as \(p(\theta _H)\). The parameter S denotes \({ sincerity}\), which reflects the perceived persuasiveness of a statement.

The second force, aversion to lying, is denoted as \({\omega \cdot \chi (S,Q)}\). Here, \({\chi (S,Q)}\) is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 if and only if the seller signals positive sincerity but ultimately supplies a low-quality product, irrespective of the buyer’s choice. In such cases, a lying cost of \(\omega\) is incurred.

4.2 The buyer’s problem

After receiving the seller’s message and detecting \({ sincerity}\), the buyer forms her belief about the seller’s type as \(\mu (\theta |S)\) (referred to as \(r_S\) hereafter) and then chooses a price that maximizes her expected utility:

\(Q_{\theta }(S,P)\) represents the seller’s optimal quality decision. For the analysis, we adopt the pure-strategy perfect Bayesian equilibrium as the solution concept.

We introduce two additional assumptions. First, following the approach of Ellingsen and Östling (2010), we assume that the buyer possesses a weak lexicographic preference for being kind, such that \(P_H \succ P_L\) when the buyer is indifferent. This assumption implies that we can always specify the buyer’s exact choice. Second, we assume that the difference between the guilt sensitivity of the two types is significantly large, such that \(\theta _H> C(Q_H)-C(Q_L)-\omega> \theta _L > 0\).

4.3 Equilibrium analysis

In this subsection, we discuss the equilibrium analysis for various communication protocols. These protocols differ primarily in the \({ sincerity}\) S of the messages that they permit. A detailed proof of the equilibrium analysis can be seen in Appendix 2.

Restricted Promise: Consider \(S\in \{0,1\}\), where \(S=1\) if the seller chooses to send a restricted promise and \(S=0\) if the seller sends an empty talk. In this case, the optimal strategy profile on quality is:

There are two pooling equilibria in this scenario. In the first equilibrium, both types pool on \(S=0\), and the buyer’s best response is \(P_L\), regardless of the received message, when \(r_0 \in [0, \frac{3}{4})\). Consequently, both types of sellers respond according to \(Q_{\theta }(S,P)\) and play \(Q_L\). This is the empty-talk equilibrium.

In the second equilibrium, both types of sellers pool on \(S=1\), and the buyer always chooses to trust,Footnote 4 selecting \(P_H\) if the prior \(p(\theta _H) \in (\frac{3}{4}, 1]\). Consequently, cooperation \((P_H, Q_H)\) can be achieved between a seller of type \(\theta _H\) and the buyer, whereas a seller of type \(\theta _L\) chooses to betray the buyer’s trust. This is the limited sincerity pooling equilibrium.

Message-select: Let us consider \(S\in \{0,1,...,N\}\) where N is not sufficiently large, such that \(\frac{C(Q_H)-C(Q_L)-\omega }{\theta _L} > N \ge 2\). In this case, the seller must choose between using empty talk or sending messages with limited but distinguishable levels of sincerity (\(S>0\)). Here, the seller’s optimal quality decision is

In this scenario, the equilibria are qualitatively similar to restricted promise communication. We observe an empty talk equilibrium and multiple limited sincerity pooling equilibrium where \(S_{\theta _H}=S_{\theta _L}=\alpha\) for all values of \(\alpha\) in the range \(N\ge \alpha > 0\). Similarly, cooperation \((P_H,Q_H)\) can only be achieved between a seller of type \(\theta _H\) and the buyer in those limited sincerity pooling equilibria.

Free-form Communication: Consider \(S \in \{0,1,...,N\}\), where N is sufficiently large: \(\exists\) \(N\ge k > 2\) such that

There exist some statements that are sufficiently sincere (\(S\ge k\)) that even a seller of type \(\theta _L\) keeps their promise. Here, the seller’s optimal quality decision is

In this case, in addition to the multiple limited sincerity pooling equilibria wherein \(\forall S\) in \(k-1> S > 0\), there are two other types of equilibria where both types of sellers cooperate with the buyer.

The first type is the high sincerity pooling equilibrium, where both types of sellers tend to pool on highly sincere statements. Here, \(S_{\theta _H}=S_{\theta _L}=\alpha\) for all values of \(\alpha\) in the range \(N\ge \alpha > k\). The buyer’s best response is \(P_H\), given \(N \ge S \ge k\), and \(P_L\) otherwise. Both types of sellers ultimately achieve \((P_H,Q_H)\).

The second type is the high sincerity separating equilibrium, where the two types of sellers send different highly sincere statements. In this equilibrium, \(N\ge S_{\theta _H}=\alpha \ge k\), \(N\ge S_{\theta _L}=\beta \ge k\), where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are distinct. Similarly, the buyer’s best response is \(P_H\), given \(N \ge S \ge k\), and \(P_L\) otherwise. Both types of sellers can achieve \((P_H,Q_H)\) in this equilibrium.

Restricted Threat: In our framework, sincerity is linked to the psychological costs associated with guilt aversion and aversion to lying. This suggests that messages intended to promote cooperative behavior should signal positive intentions or show a certain level of commitment. However, the restricted threat that a sender can employ, which underscores the non-cooperative outcome (\(P_L, Q_L\)), lacks such a commitment. Consequently, it’s reasonable to assume that \(S = 0\) in scenarios involving this kind of threat. Therefore, in treatments with a restricted threat, we expect that both sellers and buyers will exhibit behavior similar to what is observed in the baseline scenario.

4.4 Hypotheses

The theoretical framework and equilibrium analysis provide directional hypotheses for the experiment.

Hypothesis I

Cooperation is more likely under the restricted promise, message-select, and free-form treatments than under the baseline treatment.

Limited sincerity pooling equilibria clearly exist in all three communication cases analyzed. Thus, when involving a promise, these three communication treatments would result in more cooperation than a treatment where communication is not allowed (i.e., the baseline).

Hypothesis II

The cooperation rate is higher under the free-form treatment than under the restricted promise and message-select treatments.

According to the equilibrium analysis, a seller of type \(\theta _H\) always cooperates when offered a high price in the game, whereas a seller of type \(\theta _L\) only cooperates when the message is sufficiently sincere. Consequently, cooperation is more likely to occur when the communication contains a sufficiently high level of sincerity than when the sincerity level is insufficiently high. We assume that both the restricted promise treatment and the message-select treatment exhibit an insufficient level of sincerity. Conversely, under the free-form treatment, the seller has the freedom to write messages with a sufficiently high level of sincerity. We further investigate the validity of this assumption through an analysis of the experimental data.

Hypothesis III

The restricted threat treatment does not lead to a higher cooperation rate than the baseline treatment.

Given that no commitments or positive signals are conveyed when the seller issues a threat, it involves no psychological cost. Consequently, we hypothesize that the players’ choices under the restricted threat treatment will be comparable to those in the baseline treatment.

5 Results

5.1 Overview

We first present an overview of our comparison of treatments and cooperation levels to correspond with our hypotheses. Then, we explore the high price and high quality choices respectively.

RESULT 1a: The restricted promise, message-select, and free-form treatments have higher cooperation rates than the baseline treatment.

RESULT 1b: The cooperation rate is higher under the free-form treatment than under the restricted promise and message-select treatments.

RESULT 1c: The cooperation rate is not significantly different between the restricted promise and message-select treatments.

RESULT 1d: The cooperation rate is not significantly different between the restricted threat treatment and the baseline treatment.

Figure 2 displays the distribution of outcomes as a result of each treatment. Our findings indicate that the effects of the baseline and restricted threat treatments are not significantly different, whereas the three treatments with promise opportunities outperform the baseline treatment. Notably, the message-select treatment promotes cooperation as effectively as the restricted promise treatment, but both are less effective than the free-form treatment.

Across all treatments, the most common outcomes are low price–low quality and cooperation on high price–high quality. Less than 2% of the paired players choose low price–high quality.

Statistical support for RESULT 1 (a–d) can be found in Table 2, where we present pairwise comparisons of cooperation under each treatment. Each cell in the table displays the marginal effect and clustered standard error obtained from one regression. We conduct probit regressions of cooperation on treatment dummies for which the dependent variable is cooperation, taking a value of 1 if the buyer and seller coordinate on high price–high quality and 0 otherwise. The main independent variable is the treatment, with the round fixed-effects being controlled. As cooperation is the joint outcome of the decisions made by each player, we also control for the gender, social preferences, and risk preferences of both the buyer and the seller.

The overall results provide support for Hypotheses I–III. Specifically, the free-form treatment outperforms the restricted promise and message-select treatments, and the restricted promise and message-select treatments outperform the baseline treatment. However, the restricted threat treatment does not perform significantly better than the baseline treatment and fares worse than the restricted promise treatment.

RESULT 2: A larger number of buyers choose a high price under the restricted promise, message-select, and free-form treatments than under the baseline treatment. Furthermore, more buyers opt for a high price under the free-form treatment than under the restricted promise and message-select treatments. However, there is no significant difference in the high-price ratio between the restricted promise and message-select treatments. Additionally, the high-price ratio is not significantly different between the restricted threat and baseline treatments.

RESULT 3: A larger number of sellers choose high quality under the restricted promise, message-select, and free-form treatments than under the baseline treatment. Furthermore, more sellers offer high-quality products under the free-form treatment than under the restricted promise and message-select treatments. However, there is no significant difference in the high-quality ratio between the restricted promise and message-select treatments. Additionally, the high-quality ratio is not significantly different between the restricted threat and baseline treatments.

Figure 3 presents an overview of the ratios of high-price (left panel) and high-quality (right panel) choices across all treatments. The error bars indicate the standard errors. We observe a consistent trend in both variables: the ratio for the restricted threat treatment is equivalent to that of the baseline treatment, while the ratios for the other three treatments surpass that of the baseline. Additionally, the ratios for the restricted promise and message-select treatments are not significantly different from each other but are significantly lower than the ratio for the free-form treatment.

The statistical support for RESULTS 2 and 3 is summarized in Table 3, where we present pairwise comparisons of the ratios of the high-price and high-quality choices made under each treatment. Each cell documents the marginal effect and clustered standard error from one regression. To accommodate the binary dependent variable, we conduct probit regressions of high price or high quality on the treatment dummies. On the left of the table, the dependent variable is high price, which takes a value of 1 if the buyer chooses to offer a high price and 0 otherwise. On the right of the table, the dependent variable is high quality, which takes a value of 1 if the seller chooses to offer a high-quality product and 0 otherwise. The main independent variable is treatment, with the round fixed effects and the decision-maker’s gender, social preference and risk preference controlled.

5.2 Restricted communication

In Sect. 5.1, Fig. 2 illustrates that the ratio of cooperation achieved under the restricted promise treatment (31.71%) is twice as high as that achieved under the restricted threat treatment (15.43%). However, it is unclear whether this disparity is attributable to a reluctance to use threats or to a lower impact of a threat message under this treatment than under a promise message treatment. In this section, we investigate the distinctions between these two types of treatments to shed light on this matter.

RESULT 4: In the restricted threat treatment, sellers send a significantly higher number of blank messages compared to the restricted promise treatment. The effectiveness of these blank messages in promoting cooperative behavior is similar across both treatments.

To ensure that promises or threats are not made involuntarily, our game always provides sellers with the option to remain silent by sending a blank message under any of the communication treatments. As shown in Fig. 4, the ratio of blank messages sent is significantly lower under the restricted promise treatment (9.14%) than under the restricted threat treatment (26.86%).Footnote 5 The error bars indicate the standard errors.

Data from Table 4 shows that when blank messages are sent, the ratios of high-price choices are 12.5% under the restricted promise treatment and 18.09% under the restricted threat treatment. The ratios of high-quality choices are 9.38% and 6.38% for these treatments, respectively. Given the relatively small sample size of blank messages, Mann–Whitney U tests were employed for these comparisons. We found no significant differences in both high-price and high-quality choices between the two treatments (P=0.47 and P=0.57, respectively). Consequently, the effectiveness of blank messages in fostering cooperative behavior is similar across both treatments (P=0.98), with cooperation rates remaining low at approximately 6% in each treatment.

RESULT 5 When the use of blank messages is excluded, the restricted promise treatment remains more effective than the restricted threat treatment in generating cooperation.

As indicated in Table 4, when a promise is made under the restricted promise treatment, the ratios of high-price and high-quality choices are \(53.77\%\) and \(34.39\%\), respectively. These ratios are significantly higher than the corresponding ratios (\(35.55\%\) and \(19.14\%\), respectively) when a threat is made under the restricted threat treatment. Therefore, the cooperation rate resulting from a promise made under the restricted promise treatment is twice that resulting from a threat made under the restricted threat treatment. The finding that making a threat is much less effective than making a promise helps to explain why a majority of players choose not to threaten their counterparts by sending a blank message.

RESULT 5 is further supported by the statistical analysis presented in Table 5, which includes comparisons of the restricted promise and restricted threat treatments. Similar to the previous regressions, each cell in the table documents the marginal effect and clustered standard error at the individual level from one regression, with the round fixed effects controlled. In regressions involving the high-price variable, we also control for the buyer’s gender, social preference, and risk preference. For regressions involving the high-quality variable, we control for the seller’s gender, social preference, and risk preference. In regressions involving cooperation, the characteristics of both the buyer and the seller are controlled. In all three regressions, the promise variable is found to be significant at the 1% level.

5.3 Free-form communication

5.3.1 Classification

To comprehend the contents of the messages, we adopt a coordination game to classify the messages gathered under the free-form communication treatment, similar to the approach used by Houser and Xiao (2011). The message evaluators are provided with the instructions given under the free-form communication treatment and tasked with making binary choices (Yes/No) regarding each dimension outlined in Table 6.

The evaluation task in our study encompassed four dimensions: promise, threat, honesty, and humor. The impacts of promises and threats on cooperative behavior have been extensively explored in economic literature (Charness & Dufwenberg, 2006, 2010; Cooper & Kühn, 2014; Ellingsen & Johannesson, 2004; He et al., 2017). These concepts are integral to understanding how commitments and deterrents influence decision-making processes in various economic contexts. In addition, we draw from social psychology to incorporate the notions of honesty and humor into our analysis (Brambilla et al., 2011; Goodwin et al., 2014). Social psychology research underscores how moral and sociability traits influence perceptions and evaluations of others. Notably, warmth, encompassing both morality and sociability, plays a crucial role in how we gather information about others, with morality being a particularly vital factor in human cooperation. In the context of our game, honesty serves as an indicator of morality, while humor signals sociability. These two aspects are essential for understanding how communication influences social dynamics.

The evaluators are aware that these categories are not mutually exclusive. They were compensated according to the consistency of their evaluations regarding the dimensions of three randomly selected messages with the most common evaluations in the session. On average, the evaluators received a payoff of 76.68 RMB, which included a 5 RMB show-up fee. A total of 96 evaluators were recruited for this task, and each evaluator was assigned to categorize half of the messages to control the time and ensure the evaluation quality. To address potential order effects, the messages were presented in reverse order in half of the sessions. Each evaluation session lasted approximately 50 min.

5.3.2 Contents of free-form messages

To provide a sense of how the free-form messages are classified, we start with presenting a selection of sample messages and their corresponding classifications in Table 7.

Figure 5 summarizes the results of message classifications, with error bars indicating the standard errors. Here, we observe the wide use of notions of promise (77.50%) and honesty (56.11%) in the messages. However, only approximately one fifth of the messages use humor (22.22%), and threats are rarely used (7.50%).

RESULT 6 Promises and honesty are the most commonly incorporated notions in free-form messages, with humor being present in approximately one fifth of the messages; threats are rarely used.

Next, we explore the effectiveness of each notion included in the contents of free-form messages, namely promise, threat, honesty, and humor.

We conduct probit regressions of high price, high quality, and cooperation on the classification dummies, controlling for the round fixed effects and the decision-maker’s gender, risk preference, and social preference. As depicted in Table 8, the inclusion of promise and honesty notions in free-form messages significantly enhances cooperation, while the inclusion of threat and humor notions does not yield significant effects. Moreover, a promise notion positively influences both high-price and high-quality choices, whereas an honesty notion affects high-quality choices but not high-price choices.Footnote 6 This result is in line with the social psychology literature (Brambilla et al., 2011; Goodwin et al., 2014). Honesty, as a cue for moral traits, is more closely related to seller’s trustworthiness.

RESULT 7a The inclusion of a promise notion increases the ratios of high-price and high-quality choices, thereby promoting cooperation.

RESULT 7b The inclusion of an honesty notion significantly promotes high-quality choices and cooperation.

RESULT 7c The inclusion of a threat or humor notion has no impact on the outcome.

Although we find that promise and honesty notions most effectively promote cooperation, many free-form messages contain more than one notion. To clarify this observation, Table 9 lists the interactions of classifications and their contributions to overall cooperation. In general, cooperative outcomes mostly stem from messages containing only promises, those combining promises and humor, and those combining promises, honesty, and humor. Given that threat and honesty notions rarely appear separately from other notions, RESULTS 7b and 7c are restricted to cases in which the effects come from additional threat and humor notions.

While the human evaluators provide us understanding and measurement from the human perspective, existing dictionaries like LIWC adds a different approach to identify the words used in effective and ineffective free-form messages. In Appendix 1, we provide a brief text analysis by referring to the LIWC 2015 dictionary.

5.3.3 Sincerity of messages and cooperative behavior

To investigate whether the sincerity conveyed in the messages functions as suggested in our theoretical framework, we conducted additional evaluation sessions to assess the sincerity of free-form messages. Evaluators were tasked with rating the sincerity level of messages on a scale from 0 to 10. They were compensated based on the consistency of their sincerity evaluations of six randomly selected messages, compared to other evaluations in the session, using the quadratic scoring rule (see Brier, 1950). This was to ensure that the messages were rated earnestly. The average payoff for evaluators was 79.63 RMB, which included a 10 RMB show-up fee. In total, 48 evaluators participated, each tasked to categorize all the free-form messages. To mitigate potential order effects, messages were presented in reverse order in half of the sessions. Each evaluation session lasted approximately 60 min.

RESULT 8: A free-form message with higher sincerity increases the likelihood of high-price and high-quality choices, thereby promoting cooperation.

Table 10 presents the results of probit regressions of high price, high quality, and cooperation on the sincerity rating. We find that messages with higher sincerity ratings significantly encourage the buyer’s cooperative behavior (i.e., high price), the seller’s cooperative behavior (i.e., high quality), and result in more overall cooperation (\(P_H, Q_H\)). This result validates the assumption in our framework that greater sincerity S in messages leads to a higher disutility for the sender if they disappoint others. Consequently, a message’s higher sincerity level correlates with more cooperative behavior from both sides due to the increased guilt aversion experienced by the seller and the anticipated increase in guilt aversion from the buyer.

Upon further regression of sincerity on each of the notion dummies (as shown in Table 11), we observe that sincerity is positively correlated with both the promise and honesty notions (P < 0.01 for both), whereas there is no significant change with the inclusion of either the threat or humor notions.

5.4 Message-select vs. free-form communication

The overall comparison of the treatments in Sect. 5.1 indicates a lower level of cooperation under the message-select treatment than under the free-form treatment. This result can be attributed to two possible reasons. First, the sellers under the message-select treatment might not select messages effectively. For instance, they might send a limited number of messages conveying promise and honesty notions, resulting in a reduced willingness of buyers to cooperate. Second, the impact of sending messages containing the same notions might differ between the message-select and free-form treatments.

To understand which of the above two reasons drives the observed difference in the effectiveness of the treatments, we first compare the notions contained in messages under the message-select treatment with those in messages under the free-form treatment. Subsequently, we compare the effects of the same notions in messages under these two treatments.

RESULT 9 The composition of notions is similar between the message-select and free-form communication treatments.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the percentages of promise, threat, honesty, and humor notions are very similar between the message-select and free-form treatments. The error bars represent the standard errors. Table 12 presents the results of probit regressions, which confirm the lack of a significant difference in the percentages of messages conveying any of the four notions. Overall, the composition of the notions is comparable between the two treatments. In fact, the use of effective notions (promise and honesty) is slightly more frequent under the message-select treatment than under the free-form treatment, although this difference is not significant. Hence, the difference in effectiveness between the two treatments cannot be attributed to the ineffective use of notions.

Next, we investigate the second possible reason for the difference in effectiveness between the two treatments: whether the effectiveness of the same notion differs between the message-select treatment and the free-form treatment. The data presented in Table 13 illustrate this phenomenon.

When we consider the promise notion, we observe higher ratios of high-price and high-quality choices under the free-form message treatment (68.10% and 52.33%, respectively) than under the message-select treatment (53.69% and 37.58%, respectively). Consequently, the rate of cooperation is also higher under the free-form treatment (51.97%) than under the message-select treatment (36.91%) when the promise notion is included.

Similarly, when we consider the honesty notion, we observe higher ratios of high-price and high quality choices and cooperation under the free-form message treatment (68.81%, 55.45%, and 54.95%, respectively) than under the message-select treatment (54.56%, 37.05%, and 36.61%, respectively).

The rates of cooperation do not differ significantly between the two treatments when threat or humor notions are included.

RESULT 10. The notions of promise and honesty play a more significant role in fostering cooperation under the free-form treatment than under the message-select treatment.

Statistical support for this finding can be found in Table 14, where we compare the effects of each notion between the message-select and free-form treatments. In the analysis, we include observations associated with each of the four notions in four probit regressions of cooperation on the free-form treatment dummy. Each cell in the table documents the marginal effect and the clustered standard error at the individual level from one regression while controlling for the round fixed effects and the social and risk preferences of the buyer and seller.

The results indicate that messages containing promise or honesty notions are significantly more effective in promoting cooperation under the free-form treatment than under the message-select treatment, at a significance level of 5%. However, no significant differences with respect to the effects of threat and humor notions are observed between these two treatments.

5.5 Dynamics of communication

To understand how sellers’ communication behavior evolves across different communication treatments, we conducted a detailed analysis by treatment. Our analysis begins with the two restricted communication treatments, followed by the comparisons of message-select and free-form treatments treat, in terms of message notions.

RESULT 11: Sellers increasingly send restricted promises over time in the restricted promise treatment, while there is no discernible trend regarding the use of restricted threats in the restricted threat treatment.

Figures 7a, b illustrate the time trends in the proportion of sellers opting for either the restricted threat or restricted promise within their respective treatments. We note a gradual upward trend in the adoption of restricted promises, suggesting a learning curve where sellers increasingly understand the benefits of using such promises. In contrast, the usage pattern of restricted threats displays no consistent trend across different rounds, possibly due to their limited effectiveness within the parameters of our game. Statistical support for this finding can be found in Table 15, where probit regressions were conducted on the binary message choice against round variables, while controlling for the sellers’ gender, risk preference, and social preference. In line with earlier analyses, marginal effects were assessed, and standard errors were clustered at the individual level. The frequency of sellers issuing restricted promises exhibits a marginal yet progressive increase over time (P = 0.052). On the other hand, the employment of restricted threats shows no significant trend (P = 0.715).

We further explore the dynamics of message choice in the message-select and the free-form treatments by examining the time trends of each notion by treatment, as depicted in Figs. 8a and 8b.

RESULT 12. In the free-form treatment, sellers gradually increase their use of messages incorporating the notion of honesty or humor, while there is no evident time trend for any notion categories in the message-select treatment.

As documented in Table 16, in the message-select treatment, the use of messages incorporating each notion fluctuates over time, with no evident trend observed in probit regressions of the notion dummy on the round variables (P > 0.1 for all notion categories). Conversely, in the free-form treatment, there is a gradual increase in the use of messages incorporating notions of honesty or humor (P = 0.045 and P = 0.002, respectively), while no significant trends are observed for the promise and threat notions (P > 0.1 for both notion categories).

5.6 The treatment effect of sending promises

Finally, we shift our attention to examining whether the effect of sending a promise varies across treatments. Specifically, we compare the treatment effects of sending a promise between the restricted promise, message-select, and free-form treatments. This comparison is intended to clarify whether the differences in treatment outcomes are indeed influenced by how the message is constructed or selected.

Theoretically, we can conduct a similar analysis regarding the treatment effect of sending a threat. However, we refrain from drawing any conclusions in this regard because of the extremely small sample of threat notions sent under the message-select and free-form treatments.

RESULT 13. Under the free-form treatment, the promise notion significantly promotes cooperation compared with the message-select and restricted promise treatments. However, no significant differences are observed when comparing the restricted promise treatment with the message-select treatment in terms of the impact on cooperation.

The promise notion is prevalent, appearing in more than 77% of the messages sent under any of the restricted promise, message-select, and free-form treatments. When a message containing a promise notion is sent, both sellers and buyers exhibit an increased inclination to cooperate under the free-form treatment, as evidenced by the data in Table 17 and the regressions documented in Table 18. The ratios of high-price and high-quality choices are significantly higher under the free-form treatment than under the restricted promise and message-select treatments.

Conversely, there are no discernible differences between the choices of the sellers and buyers under the restricted promise and message-select treatments. Cooperation rates are also similar between these two treatments.

6 Conclusions

This paper investigates the reasons underlying the effectiveness of free-form communication in promoting efficient outcomes. To achieve this, we use a sequential social dilemma game wherein the buyer proposes a price and the seller selects a quality level. We examine five treatments: no communication (i.e., the baseline), a restricted promise, a restricted threat, a message selected from a set of previously constructed free-form messages, and a self-constructed free-form message.

We observe that the cooperation rate under the message-select treatment is equivalent to that under the restricted promise treatment but significantly lower than that under the free-form treatment. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that the restricted promise treatment significantly enhances cooperation, whereas the restricted threat treatment shows no improvement compared with the baseline treatment.

Following Ellingsen and Johannesson (2004) and Vanberg (2008), who introduce the concepts of lying aversion and guilt aversion to explain the superiority of a restricted promise over no communication, we propose a similar rationale to elucidate why free-form communication surpasses a restricted promise in terms of effectiveness. Our hypothesis is based on the assumption that individuals experience a higher level of disutility when sending messages using their own words than when they rely on pre-formulated promises. To capture this phenomenon, we introduce the concept of sincerity, which quantifies the persuasiveness of a statement, leading to the identification of new Pareto-efficient equilibria in free-form communication.

Our work is inspired by the theoretical and empirical efforts of economists and psychologists who have investigated the function and emergence of language (e.g., Blume et al., 1998; Bryan et al., 2011; 2013; Chou, 2015; Cremer et al., 2007; Fillenbaum & Rapoport, 1971; Hong & Zhao, 2017; Rubinstein, 2000; Selten & Warglien, 2007). Focusing on the meaning of language in the context of a social dilemma, we conducted a content analysis with the assistance of 96 incentivized evaluators to categorize the notions. Our results show that free-form messages predominantly convey promises and honesty, which are also the most effective notions for promoting cooperative behavior. This indicates that our participants have an accurate perception of which notions are most effective in a natural language context. Additionally, while similar notions are present in both message-select and free-form messages, the effectiveness of the same message is reduced when it is selected rather than self-constructed by the sender. This finding confirms that the self-constructed nature of free-form communication is the key factor that makes it more effective than other tested means of communication: although the content of the message matters, its self-constructed nature plays a crucial role in its sincerity and, consequently, its impact.

Furthermore, 48 additional incentivized evaluators were employed to rate the sincerity of the messages. We found that cooperative behavior in both sellers and buyers increases with the sincerity of the messages, and that the sincerity rating is higher with the inclusion of promise and honesty notions. Our dynamic analysis of communication behavior revealed that individuals gradually learn to send more promises in the restricted promise treatment and more honesty and humor notions in free-form messages.

Although free-form communication consistently promotes efficient outcomes, the factors driving its effectiveness might differ across environments. It would be interesting to discuss the possibility of a more universal model that would explain our findings and align with those of other studies. The effectiveness of communication may be related to the role of additional content in reducing social distance as demonstrated in games with cooperation or coordination opportunities (see Coffman & Niehaus, 2020; Dugar & Shahriar, 2018; Mohlin & Johannesson, 2008; Wang & Houser, 2019). While social distance may not be the primary concern in games with more pronounced conflicts (e.g., Turmunkh et al., 2019), type signaling may still account for the superior performance of free-form communication over restricted communication. A comparison of games that span the spectrum from pure coordination to zero-sum scenarios would be valuable in terms of comprehending the dominant functions at play in each environment. By systematically examining games with varying degrees of conflict, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that contribute to the effectiveness of free-form communication in different game settings. This avenue of research could shed light on the nuanced dynamics of communication and cooperation in diverse scenarios.

This paper provides insights into essential aspects of the mechanisms by which the sincerity of natural language communication impacts the outcomes of sequential social dilemma games. However, further experimental and theoretical research is necessary to study the effects of free-form communication in other social and economic environments and thus deepen our understanding. Exploring the role of natural language communication in diverse contexts will provide valuable insights into the broader implications of such communication for cooperation and general interactive decision-making processes.

Notes

Page 4, lines 16–18.

The message-select treatment was implemented in November 2020 to allow time to organize and program all of the messages as options into the z-Tree program (Fischbacher, 2007).

The table 19 in the appendix offers comprehensive details on demographic variables, risk, and social preferences.

The buyer’s price decision on the off-equilibrium path depends on her updated belief.

Z = 4.79, P < 0.001 for probit regressions of blank messages on treatment dummies, controlling for gender, social preference, risk preference, and round fixed effect; clustered standard errors are corrected at the individual level.

It is noteworthy that each notion is represented by a binary dummy in our analysis. Messages encompassing more than one notion may have multiple dummies set to one.

Pronouns and conjunctions are omitted from this analysis.

References

Aumann, R. (1990). Nash equilibria are not self-enforcing. Economic decision making: Games, econometrics and optimisation (pp. 201–206).

Azrieli, Y., Chambers, C. P., & Healy, P. J. (2018). Incentives in experiments: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 126(4), 1472–1503.

Ben-Ner, A., Putterman, L., & Ren, T. (2011). Lavish returns on cheap talk: Two-way communication in trust games. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(1), 1–13.

Blume, A., & Ortmann, A. (2007). The effects of costless pre-play communication: Experimental evidence from games with pareto-ranked equilibria. Journal of Economic Theory, 132, 274–290.

Blume, A., DeJong, D. V., Kim, Y.-G., & Sprinkle, G. B. (1998). Experimental evidence on the evolution of meaning of messages in sender–receiver games. The American Economic Review, 88(5), 1323–1340.

Bochet, O., Page, T., & Putterman, L. (2006). Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 60, 11–26.

Bornstein, G., & Rapoport, A. (1988). Intergroup competition for the provision of step-level public goods: Effects of preplay communication. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(2), 125–142.

Brambilla, M., Rusconi, P., Sacchi, S., & Cherubini, P. (2011). Looking for honesty: The primary role of morality (vs. sociability and competence) in information gathering. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(2), 135–143.

Brandts, J., & Cooper, D. J. (2007). It’s what you say, not what you pay: An experimental study of manager-employee relationships in overcoming coordination failure. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(6), 1223–1268.

Brandts, J., Cooper, D. J., & Rott, C. (2019). Communication in laboratory experiments. Handbook of research methods and applications in experimental economics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Brier, G. W. (1950). Verification of forecasts expressed in terms of probability. Monthly Weather Review, 78(1), 1–3.

Bryan, C. J., Walton, G. M., Rogers, T., & Dweck, C. S. (2011). Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(31), 12653–12656.

Bryan, C. J., Adams, G. S., & Monin, B. (2013). When cheating would make you a cheater: Implicating the self prevents unethical behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(4), 1001.

Budescu, D. V., & Wallsten, T. S. (1985). Consistency in interpretation of probabilistic phrases. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36(3), 391–405.

Budescu, David V., & Wallsten, T. S. (1995). Processing linguistic probabilities: General principles and empirical evidence. In Psychology of learning and motivation (vol. 32, pp. 275–318). Elsevier.

Budescu, D. V., Weinberg, S., & Wallsten, T. S. (1988). Decisions based on numerically and verbally expressed uncertainties. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 14(2), 281.

Cason, T. N., & Mui, V.-L. (2015). Rich communication, social motivations, and coordinated resistance against divide-and-conquer: A laboratory investigation. European Journal of Political Economy, 37, 146–159.

Charness, G. (2000). Self-serving cheap talk: A test of Aumann’s conjecture. Games and Economic Behavior, 33(2), 177–194.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnership. Econometrica, 74(6), 1579–1601.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2010). Bare promises: An experiment. Economics Letters, 107(2), 281–283.

Chou, E. Y. (2015). What’s in a name? The toll e-signatures take on individual honesty. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 84–95.

Coffman, L., & Niehaus, P. (2020). Pathways of persuasion. Games and Economic Behavior, 124, 239–253.

Cooper, D. J., & Kai-Uwe, K. (2014). Communication, renegotiation, and the scope for collusion. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 6(2), 247–78.

Cooper, R., DeJong, D. V., Forsythe, R., & Ross, T. W. (1989). Communication in the battle of the sexes game: some experimental results. The RAND Journal of Economics, 20, 568–587.

Cremer, J., Garicano, L., & Prat, A. (2007). Language and the theory of the firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(1), 373–407.

Crosetto, P., & Filippin, A. (2013). The “bomb’’ risk elicitation task. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47(1), 31–65.

Duffy, J., & Feltovich, N. (2002). Do actions speak louder than words? An experimental comparison of observation and cheap talk. Games and Economic Behavior, 39(1), 1–27.

Dugar, S., & Shahriar, Q. (2018). Restricted and free-form cheap-talk and the scope for efficient coordination. Games and Economic Behavior, 109, 294–310.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2004). Promises, threats and fairness. The Economic Journal, 114(495), 397–420.

Ellingsen, T., & Östling, R. (2010). When does communication improve coordination? American Economic Review, 100(4), 1695–1724.

Farrell, J. (1987). Cheap talk, coordination, and entry. The RAND Journal of Economics, 18, 34–39.

Fehrler, S., Fischbacher, U., & Schneider, M. T. (2020). Honesty and self-selection into cheap talk. The Economic Journal, 130(632), 2468–2496.

Fillenbaum, S., & Rapoport, A. (1971). Structures in the subjective lexicon. Academic Press.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Goodwin, G. P., Piazza, J., & Rozin, P. (2014). Moral character predominates in person perception and evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(1), 148.

He, S., Offerman, T., & Van De Ven, J. (2017). The sources of the communication gap. Management Science, 63(9), 2832–2846.

Hong, F., & Zhao, X. (2017). The emergence of language differences in artificial codes. Experimental Economics, 20, 924–945.

Houser, D., & Xiao, E. (2011). Classification of natural language messages using a coordination game. Experimental Economics, 14(1), 1–14.

Ismayilov, H., & Potters, J. (2016). Why do promises affect trustworthiness, or do they? Experimental Economics, 19, 382–393.

Kahan, J. P., & Rapoport, A. (1984). Social psychology and the theory of games: A mixed-motive relationship. Representative Research in Social Psychology, 14, 65–71.

Lundquist, T., Ellingsen, T., Gribbe, E., & Johannesson, M. (2009). The aversion to lying. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 70(1–2), 81–92.

Mohlin, E., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Communication: Content or relationship? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65(3–4), 409–419.

Rabin, M. (1994). A model of pre-game communication. Journal of Economic Theory, 63(2), 370–391.

Rapoport, A. (2012). Experimental studies of interactive decisions (Vol. 5). Springer.

Rubinstein, A. (2000). Economics and language: Five essays. Cambridge University Press.

Sally, D. F. (1995). Conversation and cooperation in social dilemmas. Rationality and Society, 7, 58–92.

Selten, R., & Warglien, M. (2007). The emergence of simple languages in an experimental coordination game. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(18), 7361–7366.

Turmunkh, U., Van den Assem, M. J., & Van Dolder, D. (2019). Malleable lies: Communication and cooperation in a high stakes tv game show. Management Science, 65(10), 4795–4812.

Vanberg, C. (2008). Why do people keep their promises? An experimental test of two explanations. Econometrica, 76(6), 1467–1480.

von Furstenberg, G. M., & Wallsten, T. S. (1990). Measuring vague uncertainties and understanding their use in decision making. In Acting under uncertainty: Multidisciplinary conceptions (pp. 377–398). Springer.

Wallsten, T. S., Budescu, D. V., Rapoport, A., Zwick, R., & Forsyth, B. (1986). Measuring the vague meanings of probability terms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 115(4), 348.

Wallsten, T. S., Budescu, D. V., & Zwick, R. (1993). Comparing the calibration and coherence of numerical and verbal probability judgments. Management Science, 39(2), 176–190.

Wang, S., & Houser, D. (2019). Demanding or deferring? An experimental analysis of the economic value of communication with attitude. Games and Economic Behavior, 115, 381–395.

Zwick, R., Carlstein, E., & Budescu, D. V. (1987). Measures of similarity among fuzzy concepts: A comparative analysis. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning, 1(2), 221–242.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research received funding support from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Smith Experimental Economics Research Center and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72371090). We extend our gratitude to the guest editors and two anonymous referees for their insightful feedback. We are also thankful for the valuable comments from Jun Feng, Lata Gangadharan, Philip Grossman, Xi Zhi Lim, Delong Meng, Erte Xiao, and attendees at seminars at George Mason University, McMaster University, Monash University, University of Guelph, Wichita State University. Additionally, we appreciate the feedback received at the ESA World Meeting (Lyon), the 16th Australian and New Zealand Experimental Economics Workshop, the ESA Global Online Around-the-Clock Meetings, and the China Behavioral and Experimental Economics Forum (Shanghai). The replication material for the study is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YR927.

Appendices

Appendix 1. A different approach of text analysis

To explore the content of free-form messages from another angle, we apply text analysis using the LIWC 2015 dictionary. Figure 9 provides a summary of the most commonly used words in these messages,Footnote 7 focusing on those occurring in more than 1% of the total words.

We categorized the messages based on their ability to promote cooperation into two groups: effective and ineffective messages. Effective messages led to high price and high quality outcomes, signifying successful cooperation, whereas ineffective messages failed to foster cooperation. Our analysis shows that terms linked with promises, such as“high price,” “high quality,” and “high,” are prominently used in both types of messages. However, these terms are about 20% more frequent in effective messages, underscoring the importance of clear goals in achieving cooperative outcomes. For example, a typical effective message might be: “Please raise a high price, and I will sell you a high-quality product”.