Abstract

We offer a novel test of whether non-binding goals set ahead of a task are effective motivators, taking into account that individuals in principle could easily revise these goals. In our setting, subjects either set a goal some days prior to an online task (early goal) or right at the start of the task (late goal). Two further treatments allow for (unanticipated) explicit revision of the early goal. We observe that (i) early goals are larger than late goals; (ii) subjects who set early goals work more than those who only set a late goal if they explicitly revise their goal and are reminded about their revised goal. A secondary contribution of our paper is that our design addresses a treatment migration problem present in earlier studies on goals that stems from the fact that subjects in a ‘no goals’ control condition may privately set goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

When deciding whether and how much to study, work, diet, or exercise, people often have a tendency to overemphasize present costs relative to future benefits. As a consequence, self-control problems arise in that people study, work, or exercise less and eat more than they initially thought is optimal. To engage in self-regulation, people can set goals for themselves some time before facing the task (early goals) when they are not yet tempted to shirk. But such personal goals are non-binding. Thus, when people actually face the task and the temptation to shirk, they may simply change their mind and revise their goal. This raises two empirical questions that the literature has not directly addressed and which we tackle in this paper: Are early goals designed as self-regulation tools? And are early goals effective in regulating behavior despite goal revision?

We run a real-effort experiment that mimics a typical work-leisure self-control problem by offering male subjects a generous piece rate for doing the tedious, unpleasant task of counting zeros in tables of zeros and ones.Footnote 1 To allow for exposure to the usual real-life temptations while subjects work, the experiment runs online and neither requires subjects to show up at a lab nor to obey a particular schedule. To study whether subjects design early goals as self-regulation tools, and whether early goals are effective, we compare the goal and the effort between a treatment where subjects set a goal five days before the task (treatment Early) and a treatment where subjects set the goal immediately before the task (Late).

Guided by a stylized model in which an individual has present-biased preferences and sets goals, our hypothesis was that the individual tries to counteract his present bias when setting a goal in advance of the task, but not when setting it right before the task.Footnote 2 Hence, subjects should set higher goals in Early compared to Late.Footnote 3

Further, as higher goals should translate into higher effort, we expect a higher effort in Early than in Late. The latter hypothesis presumes that, when facing the task, the individual does not privately revise the early goal downward too much and/or cares at least to some extent about the early goal set days in advance. A higher effort in Early than in Late therefore would suggest that goals are effective—despite the potentially occurring private goal revision.

To examine precisely whether and to what extent subjects revise their goals, we implement two further treatments—Revise0 and Revise1. In these treatments, like in Early, subjects set a goal five days before the task. But now we explicitly allow subjects to revise their goal just before engaging in the task. Subsequently, in Revise0 subjects are reminded about their initial goal; in Revise1, they are reminded about their revised goal. Hence, the only difference between Late and Revise1 is that only subjects in Revise1 set the early goal. Comparing the effort between Late and Revise1 thereby enables us to test whether early goals are effective despite (observed) goal revision. The difference between Early and Revise0 is that subjects in Revise0 are explicitly allowed to revise their goal, whereas goal revision may only occur privately for subjects in Early. Comparing effort between Early and Revise0 thereby enables us to get a suggestive understanding of the extent of private goal revision in Early.Footnote 4

A second contribution of our design is that it addresses the treatment migration problem that arises in most experimental studies on goal setting. The typical experiment has some subjects set a goal before working on the task (treatment condition), while others simply work on the task (control condition). The researchers then test the effectiveness of goals by comparing the performance in the two conditions. Yet, the self-regulation perspective of goal theory suggests that people set goals even if not explicitly asked to. Indeed, the results of Sackett et al. (2014) show that they do so.

Consequently, a problem of treatment migration arises because subjects in the control condition may nevertheless be exposed to the ‘treatment’ of setting goals. While the prior studies referenced in the literature review are valuable for learning whether explicitly eliciting personal goals has a beneficial impact on performance, the treatment migration problem means that the intention-to-treat estimate may understate the causal effect of goal setting. As parts of the literature on goal setting find insignificant effects or low effect sizes of goals on performance, addressing the treatment migration problem is important for understanding the extent to which goals are effective self-regulation tools. The comparison of treatments Early and Late avoids the treatment migration problem because we observe the goals from the subjects in both treatments.

To preview the results, we find, first, that early goals are higher than late goals. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that subjects design early goals as self-regulation tools. When considering the treatments where we observe explicit goal revision, we also observe this pattern within subject: Subjects on average revise their early goal downward. Second, the evidence on whether early goals are effective self-regulation tools is mixed. Subjects who set an early goal work more compared to when they just set a late goal, but the effect is not statistically significant. Yet, in the treatment where subjects set an early goal, explicitly revise their goals, and are reminded about this goal, subjects work more than those who just set a late goal. At first glance, it appears surprising that we only find unambiguous support for the effectiveness of early goals in combination with explicit goal revision. One possible interpretation is that subjects who only set an early goal revise it in private, and that such private revisions undermine goal commitment.

The result that subjects provide more effort if they set an early goal and then later revise it than if they only set a late goal makes it clear that setting an early goal matters. A theoretically plausible mechanism is that the early goal serves as an anchor in goal revision, in the way one would expect if changes in the goal triggered gain-loss utility—similar to the model of Kőszegi and Rabin (2009). Yet, somewhat surprisingly, the evidence goes against this mechanism for why early goals matter: The revised goal does not differ significantly from the late goal. That is, subjects seem to be behaving as if they set a new goal, rather than revising an old one. Nevertheless, early goals matter because people still seem to strive to some extent for their high early goal. Consequently, they are more likely to achieve their revised goal than subjects who do not set an early goal—consistent with the view that both early and revised goals enter the reference point to which the individual compares performance.

Finally, our design contributes to a separate research question: Can certain frames make goals more effective? Specifically, reminding subjects about a specific goal (either the revised goal or the early goal) should make that goal more salient and the subject more likely to strive for it. Similarly, explicit goal revision may make the revised goal more salient than private revision and thus lead to lower effort. We test for these effects in two additional treatments, Revise0 and Revise1. Here we explicitly provide subjects with the opportunity to revise their goals and we subsequently remind them about either the goal that they set at date 0 or date 1. No matter which goal subjects are reminded about, we find that the effort-goal relationship tends to be larger for the recent, revised goal than for the early goal. And no matter whether goal revision is explicit or not, subjects provide the same effort.

While the latter result goes against the framing hypothesis, it provides evidence—in combination with answers to our ex-post survey—that private, self-initiated goal revisions do take place. A proper understanding of the effort-goal relationship thus requires eliciting not only early goals but also revised goals—as we do in our study.

The paper proceeds as follows. Next, we discuss the related literature. Section 3 lays out the experimental design and procedures. In Sect. 4, we present our main predictions and test these in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, we consider a number of possible mechanisms behind our findings. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2 Related literature

Our study relates to the literature on how goals influence performance. Industrial and organizational psychology studies on task performance in the workplace laid the foundations for a vast literature on goals (cf. Locke & Latham, 1990; 2013; 2019). With employees traditionally operating with vague ‘do-your-best’ goals, research has focused on examining whether employers can improve task performance with specific performance goals and by letting employees participate in setting these goals. Meta-analyses indicate that task performance increases with goal difficulty, is higher for specific compared to ‘do-your-best’ goals, and is higher for participatory or self-set goals compared to assigned goals (Epton et al., 2017; Tubbs, 1986; Mento et al., 1987; Chidester & Grigsby, 1984; Wood et al., 1987).

Next to comparing specific goals to ‘do-your-best’ goals, a number of studies compare treatments where subjects themselves choose non-binding goals with a control treatment where no goals are elicited.Footnote 5 Most studies find that self-set goals have a positive effect on performance (Anshel et al., 1992; Erbaugh & Barnett, 1986; Fan et al., 2019; Goerg & Kube, 2012; McCalley & Midden, 2002; Schunk, 1985; Smith & Lee, 1992; Smithers, 2015; West et al., 2001),Footnote 6 but some do not (Akina & Karagozoglub, 2017; Goudas et al., 1999; Hayes et al., 1985; Hinsz, 1995; Tanes & Cho, 2013). This mixed picture arises also for studies that consider the effects of goals for the performance in repeated tasks, such as weight loss (Chapman & Jeffrey, 1978; Toussaert, 2016), energy saving (Harding & Hsiaw, 2014), or studying (Clark et al., 2020; Himmler et al., 2019; van Lent, 2019; van Lent & Souverijn, 2020). Koch and Nafziger (2020) consider self-set, non-binding goals in repeated tasks and find that daily goals lead to higher effort than equivalent weekly goals.

While there is a large literature on goal setting and performance, less research has been done on goal revision. Sackett et al. (2014) elicit goals for finish times two weeks prior to a marathon. They observe that eliciting goals increases performance relative to a condition where goals were not elicited. They suggest that asking runners two weeks before the task to explicitly state the goal locks them into their early, high goal, i.e., hinders goal revision. Yet, they do not test for such goal revision. Extant studies in psychology focus on how people update their goals over multiple performance episodes after they have started striving for a goal and have received feedback about performance (e.g., Campion & Lord, 1982; Donovan & Williams, 2003; Ilies & Judge, 2005). The typical finding is that goals are adjusted upwards following success or positive feedback and downward following failure or negative feedback. In the economics literature, van Lent (2019) provides, to our knowledge, the only experimental study on goal revision. It is similar in spirit to the studies in psychology. As part of a larger survey, he asks students whether they want to set a goal for their course grade, a non-grade goal, or no goal. After students get feedback about their performance through tutorials and a midterm exam, they can revise their goal(s) in a second survey. The novelty of our approach is that we study the revision of goals prior to engaging in goal pursuit. This allows us to capture goal revision related to being tempted to work less when facing a task rather than goal revision due to good or bad news about task performance.

The topic of goal revision also relates to the literature on reference-dependent preferences. Kőszegi and Rabin (2009) offer theoretical guidance on how to model revision of reference points, and Koch and Nafziger (2016) apply these insights to modeling goal revision in a theoretical framework on which we build here. Some experimental studies address how fast new information is incorporated into the reference point, and their findings are mixed. The tournament experiment of Gill and Prowse (2012) suggests that subjects rapidly update their reference points to both their own effort choice and that of their rival. Similarly, Smith (2019) finds rapid adjustment to an exogenous change in current endowments. Nevertheless, the field data of Card and Dahl (2011), DellaVigna et al. (2017), and Thakral and Tô (2021) suggest slow updating of the reference point in other domains. Our contribution to the empirical evidence on updating of reference points is to provide evidence on the context where individuals update reference points (goals) because of time-inconsistency.

Finally, our study relates to Augenblick et al. (2015), who estimate present bias in effort using a real-effort task similar to ours. Subjects have to specify several binding plans on how to allocate effort over two dates that are a few days into the future; and they again specify plans right before providing effort. The key difference to our study is that in their setting subjects are committed to a selected effort plan (the completion bonus is contingent on providing the effort). In contrast, subjects make non-binding plans (expressed as goals) in our study, and we test whether such non-binding plans can motivate effort. Augenblick et al. (2015) find evidence for present bias in the effort domain but not in the money domain. In a similar framework, Augenblick and Rabin (2019) elicit the beliefs that individuals hold about their future effort. They demonstrate that most individuals are (partially) naïve in that they overestimate how much effort they will provide.

3 Experimental design

Our experiment has three parts that are conducted online on three different days: A goal setting part at date 0 (t), a work part at date 1 (\(t+5\) days), and a post survey at date 2 (\(t+7\) days). We randomize subjects into four different treatments. In treatments Early, Revise0, and Revise1, subjects set a goal at date 0 (goal 0). In treatment Late, subjects only set a goal at date 1 (goal 1). Subjects in Revise0 and Revise1 can revise their goal at date 1. While working, we remind subjects in Revise0 and Early about the goal they set at date 0. Conversely, in Revise1 and Late, we remind subjects about the goal that they just set a few minutes earlier at date 1. Table 1 summarizes the four treatments. Figure 1 provides the timeline of the experiment. Experimental instructions are in Online Supplement S.11.

3.1 Details of the experimental setup

3.1.1 Date 0: goal setting

The primary objective at date 0 is to elicit non-binding goals from the subjects in treatments Early, Revise0, and Revise1 for the effort that they want to provide at date 1 in the free work phase of the experiment. For completing the date-0 part of the experiment, subjects receive DKK 35 (approx. USD 5.6) in addition to their earnings from three tasks.

Productivity measure Throughout the experiment, we measure effort in a real-effort task in which subjects count the number of zeros in a series of tables consisting of zeros and ones as in Abeler et al. (2011) and Koch and Nafziger (2020). The task was chosen to mimic features of typical self-control problems in that subjects are likely to have low intrinsic motivation for it, also because it does not have any productive use.Footnote 7 We note that goals might have a different effect for tasks that are perceived as meaningful, either because individuals are intrinsically motivated for such tasks or because they are important for the individual in other ways (e.g., career goals).Footnote 8

To familiarize subjects with this real-effort task before they set goals, subjects count the zeros in as many tables as possible in three minutes (denoted mandatory work phase in Fig. 1). For each table in which they count the number of zeros correctly (completed table, henceforth), subjects receive DKK.5. The total number of completed tables in these three minutes provides us with a measure of baseline productivity at date 0 (productivity 0 for short). After the task, subjects answer a survey question on how much they like the task.

Self-competitiveness measure To ensure that subjects in Late do not guess the nature of the date 1 task and then potentially privately set goals, subjects perform an additional round of the real-effort task and an additional task that is unrelated to goal setting. Specifically, we obtain a measure of subjects’ self-competitiveness based on the procedure of Saccardo et al. (2017). For the second round of counting zeros, subjects make a choice of what share of their pay shall be (i) determined by a fixed piece rate of DKK.5 for each completed table and (ii) determined based on their performance relative to the first round. In the latter scheme, subjects receive DKK 1 (DKK 0) for each completed table in case they complete more (fewer) tables than in the first round, and DKK.5 in case of a tie.

Goal setting This part is not relevant for subjects in Late. To avoid private goal setting, we provide subjects in Late with no details about the work to be performed at date 1 except the information that is necessary for informed consent.Footnote 9

In all the other treatments, we inform subjects about the details of the free work phase at date 1 and the associated payment scheme (cf. Figure 2). We implement a declining piece rate scheme to avoid corner solutions where subjects count all the available tables (which is likely with a constant piece rate, cf. Koch & Nafziger, 2020).

We then ask subjects to set a goal for how many tables to complete in the free work phase (goal 0). That is, goals are self-set, but engagement in goal setting is exogenously induced so that all subjects state a goal. Subjects know that the work phase takes place five days after the goal setting part. We fix the time interval so that present bias can create a discrepancy between desired effort in the goal setting and work parts. Specifically, Augenblick et al. (2015) and Augenblick and Rabin (2019) demonstrate how the discounting of future real-effort costs changes drastically within the first hours and days prior to the task, whereas it is almost constant 4–30 days into the future.Footnote 10

Before setting goals, subjects have access to a slider tool that should help them to reflect about how much time it would take them to achieve a certain goal (see Fig. 3). The tool shows the estimated amount of time for reaching the goal selected with the slider (based on the productivity of the subject) along with the associated earnings and the marginal piece rate.Footnote 11 We encourage subjects to experiment with the slider before entering a goal. We tell subjects that they will be reminded about the goal while working on the task with probability 2/3—the probability reflecting the random assignment to treatments that takes place after setting goals. We stress that how much they ultimately work is entirely up to themselves; there will not be any punishment if they fail to reach their goal, and they may count more tables than their goal.

Note that we do not announce at this date that subjects (in some treatments) will have the possibility to explicitly revise their goal at date 1.Footnote 12 Announcing goal revision in Revise0 and Revise1 would complicate comparisons between Revise0 and Early as it could change the (perception of the) goals that subjects in Revise0 set at date 0, thereby interfering with the test of our main hypotheses.

Survey questions At date 0, subjects fill in background information (age, type of degree, and field of study) and the number of upcoming exams and assignments in the next month. In addition, subjects answer the general risk aversion question from Dohmen et al. (2011) and the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT, Frederick 2005). Subjects receive DKK 2 for each correct answer in the CRT. The CRT and risk aversion questions are used, among other variables, as control variables (see Online Supplement S.3 and Sect. 5 for details).

After the mandatory work (but before setting goals), we ask subjects about their time schedule for date 1. Further, we ask them how likely they think it is that they will end up having less than two hours of flexible time at date 1. These questions serve two purposes: First, they should make subjects aware of how much time they realistically can devote to working on the task at date 1. Second, they allow us to control for possible time constraints and examine the effect of resolution of uncertainty about time shocks between dates 0 and 1.

3.1.2 Date 1: work part

Date 1 takes place five days after date 0 and consists of two phases. All subjects have to complete the first phase, but they can freely choose whether and how much to work in the second phase.

Phase 1: productivity measure and goal setting In the first phase, subjects have to count the number of zeros in a series of tables for two times three minutes with a break in between. They receive DKK.5 for each correctly counted table. The first three minutes provide us with a baseline productivity measure at date 1 (productivity 1). In the break, we inform/remind subjects in all treatments about phase 2, the free work phase. In phase 2, they are free to work as much as they want under the payment scheme in Fig. 2. Similar to date 0, we ask subjects to fill in their time schedule to see if (or how) the schedule for the day has changed since date 0.

Subjects in Early then go directly to the three minutes of counting and thereafter to the free work phase. In Late, Revise0, and Revise1, we present the slider tool in the context of asking subjects to set a (new) goal. The tool is like the one at date 0—with the only difference that it uses productivity 1 as input. This way, we can see whether subjects in Revise0 and Revise1 adjust their goal in response to a change in their productivity between dates 0 and 1.

Subjects in Late set a non-binding goal for how much to work in phase 2 (goal 1), and they know that they will be reminded about that goal when working. Subjects in Revise0 and Revise1 also set a goal, and we inform them that they will be reminded about their revised goal (goal 1) with probability 1/2 and about their early goal (goal 0) with probability 1/2. We tell subjects in both Revise treatments about the goal they have set at date 0 before they (potentially) adjust their goal. Such a reminder might serve as an anchor.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, we opted to remind subjects because we would otherwise conflate measuring an intention to revise the goal with measuring whether subjects can remember their goal.Footnote 14 In addition to the earnings from the mandatory work, subjects get a fixed payment of DKK 20 for completing phase 1.

Phase 2: free work In the second phase, subjects are free to work as much as they like as long as they do not take more than 30 min between submitting answers. They are paid according to the piece rate in Fig. 2. While working, we remind them on the screen about their goal (goal 0 in Early and Revise0, and goal 1 in Late and Revise1), the number of completed tables, the piece rate that applies, and their total earnings. This design feature mirrors many real life settings where apps or other reminders help individuals keep track of their goal achievement. Henceforth, we refer to the total number of completed tables in the free work phase as effort.

3.1.3 Date 2: post survey

Two days after the work part of the experiment, subjects receive an email with a link to the post survey. Subjects receive DKK 15 for completing it plus DKK 2 for each goal they remember. The survey consists of several questions about goal setting and goal commitment; both specific to the experiment and in general (see Online Supplement S.11). In addition to some questions that could be used for exploratory research, it gives us an indication to what extent subjects in Early privately revised their goals and allows us to check that subjects in Late did not anticipate the free work task for date 1 and set a goal before date 1. The survey takes around 5 min to answer.

3.2 Sample

Several studies suggest that goals have a positive effect on the performance of men, while the effect sizes are smaller or null for women (cf. Koch & Nafziger, 2020; Smithers, 2015; Clark et al. 2020). At the same time, our study has a high cost per participant. Thus, to achieve an appropriate power for the given budget, we only recruited men for the experiment (see Online Supplement S.4 for the power analysis).

We recruited subjects from the subject pool of the COBElab at Aarhus University and, during the COVID-19 lockdown, also from the student population in the four largest Danish cities. In total, we recruited 499 subjects. Of these, 394 completed the date-0 part of the study, and 326 reached the free work part at date 1. A total of 276 subjects also completed the post survey (date 2), which we primarily use for exploratory research.Footnote 15 We discuss attrition in Online Supplement S.5. Specifically, we compare subjects who completed the date-1 (goal setting and work part) and date-2 (post survey) parts of the study with those who only completed the date-0 part. For the date-1 part, we find no indication for selection on observables. For the date-2 part, subjects who enjoy the task or who study Economics/Business are more likely to complete the date-2 part. Thus, the interpretation of the exploratory analysis that relies on the post survey should be interpreted with some caution. The treatment assignment does not explain selection into the date-1 and date-2 parts.

Our main sample consists of the 326 subjects who reached the free work part at date 1. Of these, 192 (59 percent) were bachelor students, 71 (22 percent) were master students, 10 (3 percent) were PhD or other types of students, and 53 (16 percent) were not students. Most students came from the largest study programs in Business and Economics (126 subjects, 39 percent of the sample). Subjects earned DKK 188 on average.

3.3 Procedures

We conducted all parts of the experiment online using the Qualtrics platform. When completing the consent form, subjects could select among a number of date (0, 1, 2) triplets for when to participate in the study. They then received an invitation email with a personalized link for the date-0 part of the study at midnight on the selected date. Similarly, subjects who completed date 0 (date 1) then received an email with access to the date 1 (date 2) part at midnight on the appropriate date. Subjects had to use a PC or tablet (access via smartphone was technically blocked). This was to enhance the feeling that the task is ‘work’. To prevent participants from pasting tables into a spreadsheet program to do the counting, we copy-protected tables.

We collected data November-December 2019 and March-May 2020. The break during the exam period in January and February ensured similar working conditions for all participants. Subjects knew that they would receive payments 2–6 weeks after the experiment via a standard system that allows public bodies and companies to send money to people by means of their social security number.

At date 0, we randomized subjects into either the Late treatment (with probability 1/4) or the other treatments (with probability 3/4). At date 1, we then randomized the latter subjects into either Early, Revise0, or Revise1 with equal probabilities.

4 Main hypotheses

Our hypotheses are based on a stylized framework where people have present-biased preferences (Laibson, 1997) that create a self-control problem in effort provision. We allow for partial naïvité (O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999). The model and analysis is presented in Appendix A. Here, we outline the main intuitions and summarize the main predictions (see Table 2 for an overview).

At date 0, self 0 can set goals (except in treatment Late, where the individual does not yet know about the task). At date 1, self 1 provides effort and, before doing so, can potentially revise the goal (or, in Late set a goal for the first time). The present bias causes a self-control problem in that self 0 wants a higher effort than self 1.

4.1 Goal setting

To overcome the self-control problem, self 0 sets an effort goal at date 0. Consistent with the evidence from psychology on goals (e.g., Heath et al., 1999; Locke & Latham, 2002; Wu et al., 2008) and building on the models of Koch and Nafziger (2016, 2020), we assume that a goal serves as a reference point: If the effort falls short of the goal, the individual experiences loss utility.

The present bias causes a wedge between the goals that the individual sets at date 0 compared to date 1. When setting a goal at date 0 (as in Early), self 0 wants a higher effort than self 1 and sets a goal to counteract the present bias. Such a goal can motivate self 1 to provide more effort than he would in the absence of a goal because he fears suffering a loss if he falls short of the goal. If the individual can only set a goal at date 1 (as in Late), the present bias makes him fully give in to his self-control problem. Thus, the goal in Early is larger than the goal in Late.

When the individual has the opportunity to revise his early goal at date 1, he discounts the future benefit with the true present bias—in contrast to self 0. This is the case in Revise0 and Revise1, where subjects can revise their goal before providing effort. In Early, self 1 possibly revises his goal privately. Further, because of partial naïveté, self 0 might have set a goal that is too high in that it exceeds the highest effort that self 1 would be willing to provide. Both are reasons for revising the goal downward. Yet, lowering the goal triggers loss utility. This is similar to the loss one feels when failing to reach a goal, but the loss from goal revision possibly has less weight than the loss from actually falling short of the goal (see Kőszegi & Rabin, 2009, for a further discussion of this assumption in the general context of reference point adjustments). Hence, loss aversion is a weaker motivator in the goal revision stage than at the effort stage. As a consequence, the largest goal that is ‘revision proof’ is smaller than the largest implementable early goal.

Overall, the revised or late goal at date 1 therefore is lower than the early goal set at date 0. We test this both with a between-subject comparison (Early vs. Late) and a within-subject comparison (Revise0 and Revise1). If goals set at date 0 are larger than those set at date 1, we speak of early goals as self-regulation tools. Note, however, that subjects might become more productive from date 0 to date 1. This would imply that, mechanically, they set higher goals at date 1 than at date 0. We hence control for the productivities at dates 0 and 1, respectively.

Hypothesis 1

Controlling for the respective baseline productivities,

1. (Between-subjects) Goals set in Early are larger than goals set in Late.

2. (Within-subjects) Goals set in Revise0 and Revise1 are lower at date 1 than at date 0.

4.2 Effort provision

Higher goals translate into higher effort. If the individual only sets a goal at date 1 (as in Late), this goal is set at the preferred effort of self 1, and he then achieves this goal. In contrast, as both the early and the revised goals in Early, Revise0, and Revise1 are higher than the preferred effort of self 1, effort in these treatments should exceed the effort in Late. That is, individuals do not only design early goals as self-regulation tools, but they are also effective—despite goal revision.

As effort may differ between Early, Revise0, and Revise1 (see Hypothesis 3), we test the hypothesis that early goals are effective self-regulation tools by making the following two comparisons: First, we compare effort between Early and Late. In both treatments, subjects are asked to set a goal only at a single date, and they are later reminded about that goal. Second, to test if early goal setting is effective when we allow for explicit goal revision, we test whether the effort in Revise1 exceeds the effort in Late. In both treatments, subjects are reminded about the goal they set at date 1, so treatment differences can only arise because subjects in Revise1 set an early goal at date 0 but those in Late do not.

Hypothesis 2

1. Subjects provide more effort in Early than in Late.

2. Subjects provide more effort in Revise1 than in Late.

By random assignment to treatments, the early and revised goals should not differ between Revise0, Revise1, and Early.Footnote 16 Yet, the salience of the early and revised goals may differ in these treatments. First, it seems plausible that the goal that is displayed while working on the task is the most salient (see Karlan et al., 2016, for the idea that a reminder makes an attribute salient). Second, making goal revision explicit in Revise0 and Revise1 may result in greater salience of the revised goal compared to the (possibly privately revised) goal in Early because the explicit revision grabs the (limited) attention of the individual (cf. Higgins, 1996, for salience theory in social psychology and Bordalo et al., 2020 for an economic application of salience theory to memory).

In the model, the goal that the individual strives for—the effective goal—is a combination of the early and revised goals. It is higher in Early than in Revise0 and higher in Revise0 than in Revise1. As higher effective goals result in higher effort, we expect a higher effort in Early than in Revise0, and a higher effort in Revise0 than in Revise1.

Hypothesis 3

1. Subjects provide more effort in Early than in Revise0.

2. Subjects provide more effort in Revise0 than in Revise1.

5 Empirical analysis

In this section, we first describe the main variables and the analysis plan. Then, we test our primary hypotheses (H1-H3) by comparing effort and goals in the different treatments. Finally, we comment on the robustness of the results. In Sect. 6, we examine possible mechanisms and discuss alternative explanations that could influence the results. Tables and figures with prefix S. are in the online supplement.

5.1 Main variables and analysis plan

Our main outcome variables are goal 0 (the goal set at date 0, except in Late), goal 1 (the goal set at date 1 in Late or the revised goal in Revise0 and Revise1), and effort. Table 3 provides descriptive statistics of the average goals, effort, goal achievement, and baseline productivities in the different treatments.

To test our hypotheses, we follow the pre-analysis plan and use OLS regressions (i) without control variables, (ii) with date-specific productivity measures as control variables, and (iii) with the full set of control variables (listed in Online Supplement S.3). When effort is the outcome variable, we add specifications in which we control for the respective goals, both with and without other control variables.Footnote 17 Throughout, we report p values for two-sided tests. Standardized effect sizes are summarized in Table 2. In Sect. 5.4, we discuss multiple hypothesis correction for the p values.

5.2 Goal setting (test of Hypothesis 1)

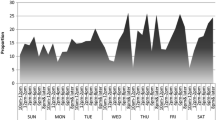

Goal revision in Revise0 & Revise1. Notes: Panel (a) shows a bar chart of the share of subjects who revise their goals in Revise0 and Revise1. Panel (b) shows within-subject differences between goal 1 and goal 0 in Revise0 and Revise1, conditional on goal revision. The box plot shows the median as well as upper and lower quartiles. Spikes extend to the largest or smallest values within 1.5 times the upper or lower quartiles, respectively

In line with Hypothesis 1.1, the goal that subjects set in Early is on average 34 tables higher than the goal that subjects set in Late. This difference is statistically significant when we control for the baseline productivity of subjects at the time of goal setting (\(p=.01\), cf. Specifications (1)-(3) in Table 4). To understand why we control for productivity despite random assignment to treatments, note that average productivity increases due to experience (cf. Table 3). This increase works against our prediction because it tends to increase the Late goal. Productivity explains 8 percent of the variance in goals between treatments.Footnote 18

Similarly, visual inspection of Table 3 and Fig. 4 indicates that subjects in the Revise0 and Revise1 treatments revise their early goal downward at date 1. Figure 5 shows in panel (a) the extensive margin of goal revision (64 percent of subjects revise their goal) and in panel (b) the intensive margin (a box plot of goal 1-goal 0). Conditional on goal revision occurring, the average subject revises his goal downward by 56 tables (49 tables when excluding an outlier with goal revision -700). In line with Hypothesis 1.2, we observe in a within-subject comparison that goal 1 is significantly smaller on average than goal 0 (\(p<.01\), cf. the intercept in Specifications (4) and (5) in Table 4; results are robust to adding controls and to excluding outliers, cf. Table S.4).Footnote 19 Notably, there is some heterogeneity in goal revision. While 45 percent of the subjects revise their goal downward (on average by 111 to a goal 1 of 167), 36 percent of the subjects keep their early goal (average goal of 293), and 19 percent actually revise their goal upwards (on average by 73 to a goal 1 of 321). Our results indicate that while most subjects have time-inconsistent goals, some people do behave in a time consistent manner.

5.3 Effort provision

Visual inspection of Table 3 and Fig. 6 indicates that effort in Late is lower than effort in the treatments where subjects set an early goal, but there appears to be little difference in effort between Early, Revise0, and Revise1. While the former pattern is in line with the view that early goals are effective self-regulation tools (Hypothesis 2), the latter pattern goes against the predictions regarding the framing of goal revision or goal reminders (Hypothesis 3). We test each of the hypotheses in turn and report the results in Tables 5 and 6 (results are robust to excluding outliers, cf. Table S.5).

5.3.1 Test of Hypothesis 2

Regarding Hypothesis 2.1, we find that effort indeed is larger in Early than in Late (23 tables on average), but this difference is not statistically significant (\(p=.281\), cf. Table 5, MWU: \(p=.405\)). Subjects exert significantly more effort in Revise1 than in Late (\(p=.011\), cf. Table 5, MWU: \(p=.023\)). This is in line with Hypothesis 2.2.

Discussion of the results The result that effort is larger in Revise1 than in Late suggests that early goals work despite goal revision (in Sect. 6.2, we discuss a number of alternative explanations for why effort may be greater in Revise1 than in Late, but we do not find support for them). Yet, the non-significant difference in effort between Late and Early casts some doubt on this. It could be that the higher early goal does not induce enough effort compared to the lower late goal. For example, subjects who only set an early goal may privately revise it (see below) and then feel neither very committed to their early goal (about which they are reminded) nor to their (less salient) privately revised goal.

Another possibility is that the non-significant difference between Early and Late is due to a lack of statistical power. The effect size of.169 is meaningful, but our ex-ante power analysis suggests that we are not sufficiently powered to detect effects of this magnitude (see Online Supplement S.4). The problem is that the standard deviation on subjects’ effort (146 and 126, respectively) is large compared to the treatment difference (23). Redoing the power analysis with the obtained effect size shows that one would need at least 900 subjects in a replication of Late and Early to obtain a power of 0.8 when controlling for productivity.

5.3.2 Test of Hypothesis 3

Regressions confirm the observation from Fig. 6 that there are no differences in effort both between Early and Revise0 and between Revise0 and Revise1 (cf. Table 6), leading us to reject Hypothesis 3.Footnote 20 However, in contrast to the rejection of Hypothesis 2.1, this rejection is not a threat to the overall hypothesis that setting early goals is an effective self-regulation tool: Hypothesis 3 relies on assumptions about exogenous parameters that are not central for the theory in Appendix A. Thus, the rejection only shows that certain frames cannot make goals more effective.

While subjects pay attention to both goals, the more recent goal 1 tends to matter more for subjects in both Revise0 and Revise1. Across separate effort regressions for Revise0, the coefficient on goal 0 (.421; Specification (1) in Table S.3) is borderline significantly smaller than the coefficient on goal 1 (.686; Specification (7); Wald chi-square test for equality of coefficients across models, \(p=.059\)), and this also holds when adding controls (\(p=.026\) and \(p=.019\), respectively).Footnote 21 For Revise1, the coefficient on goal 1 (.680; Specification (10) in Table S.3) is larger than on goal 0 (.618; Specification (4)), but this difference is not statistically significant (\(p=.681\); \(p=.854\) and \(p=.933\) when adding controls). Moreover, the recent goal 1 appears to be equally important for subjects in Revise0 and Revise1; reflected by an insignificant difference across treatments between the coefficients on goal 1 (\(p=.638\); Specifications (7) and (10)).

Discussion of the results The non-significant difference in effort between Early and Revise0 suggests that explicitly asking subjects to revise their goal does not matter for effort. One plausible explanation for this is that subjects in Early privately revise their goals and that such privately updated goals are as important as explicitly updated goals. Exploratory analysis of the responses from the post survey supports this explanation. Among the 64 responses in Early, 20 (31 percent) indicate that they privately revised their goal downward. On average, the subjects who adjust their goal do so by 62 tables, which explains almost all of their 66 table achievement gap relative to goal 0. In addition, the 44 subjects in Early who report no private revision exert effort statistically indistinguishable from their goal (\(p=.150\)).

5.4 Robustness

We report several robustness tests in Online Supplement S.6. Importantly, the result that setting an early goal leads to higher effort in the comparison Revise1 vs. Late is qualitatively robust to using median regressions, which is less affected by outliers than OLS (cf. Table S.24). The piece rate being zero for any effort larger than 900 suggests that any goal or effort beyond 900 is irrational. Excluding subjects who set a goal equal to or larger than 900 (3 subjects) or provide an effort equal to or larger than 900 (1 subject) does not alter our conclusions (cf. Tables S.4 and S.5).

Considering other outcome variables, namely average mistakes or time spent per table, we find no difference between Late and the other treatments (cf. Table S.6). However, these variables do not correlate strongly with effort (\(r=-.256\) and \(r=-.464\), respectively), which suggests that they might not be appropriate proxies for effort. For example, if a subject counts more tables, such effort may increase mistakes due to fatigue. And the impact on time spent is unclear as subjects who exert much effort in counting tables may be fast (proficient) or slow (attentive) in doing so.

Multiple hypothesis testing We present our findings in Sect. 5 without multiple hypothesis correction because the hypotheses are highly interdependent. Our main results remain at least borderline significant when correcting for multiple hypothesis testing (cf. Table 7), either controlling the family-wise error rate (FWER) using the Holm-Šidák procedure (Šidák, 1967; Holm, 1979) or the false discovery rate (FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

6 Mechanisms

In the following, we consider possible mechanisms for the significant difference in effort between Revise1 and Late. We start by discussing mechanisms that are based on the theoretical model in Appendix A. Then, we test alternative mechanisms that could explain our findings. Throughout, we often rely on the variable goal achievement, defined as the difference between a subject’s effort and goal. To estimate the marginal effect that a treatment has on the probability of reaching a goal, we use a binary goal achievement variable for goal 0 and goal 1 (equal to one if effort \(\ge\) goal and zero otherwise). Table 3 provides descriptive statistics.

6.1 Why do goals work despite goal revision? The role of the early goal

6.1.1 Does the early goal serve as a reference point in goal revision?

Our theoretical framework in Appendix A assumes that the individual has the early goal in mind and experiences loss utility if he revises the goal downward. Because early goals are higher than late goals, goal revision should not go all the way down to the level of what the late goal would have been. That is, the theory offers the between-subjects prediction that \({goal 1 }^{Revise}>{goal 1 }^{Late}\). We do find that revised goals tend to be greater than goals set for the first time at date 1 (\({goal 1 }^{Revise\,0\, \& \, Revise\,1}=241.83\) and \({goal 1 }^{Late}=229.01\)), but this difference is not statistically significant (\(p=.562\), cf. Table S.7). This result suggests that an individual experiences no substantial loss utility when revising the goal. Indeed, if setting an early goal influenced effort entirely through a higher level of goal 1, then the treatment difference between Revise1 and Late should disappear once we control for goal 1. Yet, subjects in Revise1 provide significantly more effort than subjects in Late even when controlling for goal 1 (cf. Table 5).

6.1.2 How do the early goal and the revised goal matter?

The theory in Appendix A allows for another channel through which the early goal impacts effort. Both the early and the revised goals are assumed to be ‘sticky’ in the sense that the individual compares exerted effort to a reference point that is a function of the early goal and the revised goal (see Online Supplement S.2 for a discussion on the functional form of the reference point). Indeed, the early goal seems to affect the reference point that the individual has in mind when working: Setting an early goal does increase effort and it makes subjects more likely to achieve their revised goal (even though it does not affect the level of the revised goal). Specifically, while subjects in Revise0 and Revise1 on average achieve their goal 1, subjects in Late on average fall 39 tables short of their goal 1 (\(p<.001\)).

In sum, while early goals do not appear to serve as a reference point in goal revision, they matter because individuals appear to still strive for them to some extent also after goal revision.

6.2 Alternative mechanisms

We derived our predictions based on a model where individuals are present-biased. The result that goal 0 is larger than goal 1 is consistent with the explanation that individuals set a high goal ex ante to counteract the self-control problem that arises from their present bias. In Online Supplement S.7.1, we examine alternative explanations to present bias for downward goal revision in the Revise treatments. We find no evidence for any of the following potential alternative mechanisms regarding goal revision: resolution of uncertainty or unexpected time shocks, learning (about how to perform the task or about the cost of the task), or overoptimism about future productivity.

Further, in our theoretical framework we assumed that goals serve as reference points measured in the effort dimension and that goals are (quasi-)rational. In Online Supplement S.7.2, we discuss alternative reference points such as earnings and time reference points. We find no evidence that these matter. In Online Supplement S.7.4, we discuss the rationality of goals.

A prediction of our theoretical framework is that the observed treatment differences in effort between Late and Revise1 should relate to treatment differences in goals. In the regressions, effort levels are significantly related to goals (cf. Table S.14). When controlling for goal 1 and productivity 1, the treatment difference between Revise1 and Late is significant (\(p=.013\); cf. Table S.15). This result may arise because subjects in Revise1 also strive for goal 0. Indeed, the treatment difference becomes insignificant when controlling for the first goal that subjects set in the two treatments (goal 0 in Revise1 and goal 1 in Late) and productivity (\(p=.120\); cf. Table S.15).

In Online Supplement S.7.3, we discuss robustness checks for other factors than goals for the treatment differences in effort between Revise1 and Late. First, a concern might be that learning about the task and setting goals early vs. late could influence attrition and in doing so affect treatment differences. Second, setting goals and knowing about the task in advance could increase how meaningful the task appears (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Grant, 2008), prompt additional practicing or induce people to employ certain other self-control strategies such as “if-then" plans or mental rehearsal. Third, being asked to reflect twice about the goal could increase goal commitment compared to only setting it once. Lastly, experimenter demand might bias our results. We find no evidence for these alternative explanations (see Online Supplement S.7.3).

7 Conclusion

In this study, we test for a sample of male subjects whether self-set, non-binding early goals are effective self-regulation tools even though subjects can easily revise these goals. A secondary contribution of our paper is that it addresses potential confounds of private goal setting and goal revision. Specifically, our design avoids the treatment migration problem that might be responsible for the mixed evidence found in studies comparing performance with self-set goals compared to a no-goals condition.

Our tentative results highlight the importance of setting goals in advance and making goal revisions explicit: Subjects who set a goal a few days in advance of the task set higher goals than subjects who set goals at the start of the task. Moreover, subjects who set an early goal exert more effort than subjects who only set a late goal if goal revision is explicit and subjects are reminded about their revised goal. Yet, if goal revision is not made explicit, then we fail to reject the null hypothesis that an early goal induces the same effort as a late goal. Thus, while our results reveal that goal revision does occur (also when individuals are not asked to revise their goal), they also show that these revisions do not make goals ineffective. Further, our results suggest that one cannot (and should not) prevent or alleviate goal revision by highlighting the early goal or by “hiding" the opportunity to revise goals. Yet, when interpreting the results on effort some caution should be applied: The effect sizes in this study are below those used for ex-ante power calculations, and replications are therefore warranted to draw firm conclusions regarding our hypotheses.

These tentative findings have implications both for organizations and individuals. Organizations may be sceptical about using non-binding goals to increase performance. Our results suggest that such goals do work if they are set in advance of the task and one allows for revision. For individuals, our results demonstrate the potential for early goals in connection with goal revision to be effective self-regulation tools. Lastly, our results highlight the need for researchers to recognize private goal revision. For example, when examining goal achievement, researchers should not simply rely on initially stated goals but instead elicit revised goals to avoid comparing performance to a different goal than the one that people have in mind.

However, a caveat applies to this discussion as the results are obtained for a male only sample. In this respect, our study is only a first step in understanding the effects of goal revision. While previous studies have found that goals are more effective for men than for women, it could be that a different result obtains in the presence of explicit goal revision. More broadly, it is interesting to understand why goals are less effective for women compared to men. To investigate this, many different mechanisms need to be tested in addition to goal revision. We consider these questions to be an interesting avenue for future research.

Notes

To maximize power for a data collection with a high cost per subject, we pre-registered to only recruit men (see Sect. 3.2 for details).

The literature in economics on goal setting offers several theoretical models to capture how non-binding, personal goals help people to overcome self-control problems. The basic idea in these models is that goals serve as reference points that make substandard performance painful (Suvorov & van de Ven, 2008; Jain, 2009; Koch & Nafziger, 2011; Hsiaw, 2013).

Rather than being self-regulation tools, goals might just be expectations about effort or ordinary motivators that affect, for example, intrinsic motivation. In these cases, the early goals that subjects set should not be more ambitious than the later goals on average. In fact, subjects might even set higher goals later on as they become more productive over time.

One caveat is that explicitly asking subjects to revise goals may prompt goal revision and make it more common than when such revisions are self-initiated. Hence, the comparison between these treatments may underestimate the effectiveness of early goals.

Goals can be made binding by tying them to monetary rewards (Dalton et al., 2015; Goerg & Kube, 2012; Kaur et al., 2015; Gonzalez et al., 2020) or not (Brookins et al., 2017; Corgnet et al., 2015, 2018; Cettolin et al., 2020). With the exception of Dalton et al. (2015), these studies also suggest that goals have a positive impact on performance. However, Gonzalez et al. (2020) find that it can be counterproductive to tie self-set goals to monetary bonuses because loss aversion then may induce workers to set lower goals.

In Smith and Lee (1992), 6 out of the 17 subjects in the no-goal treatment reported in an ex-post survey that they had set a goal. Consistent with the treatment migration problem described in the introduction, excluding the 6 subjects who had privately set a goal, the performance gap actually was larger for the goal treatments vs. the no-goal treatment.

Indeed, only 10 percent of the subjects report to like the task “a great deal" at date 0, and this drops to just 5 percent in the post survey.

Similarly, the effects of goals might be greater if one introduces further extrinsic motivation, e.g., by making payment conditional on subjects reaching their goal as in Kaur et al. (2015).

Subjects fill out the consent form (see Online Supplement S.11) at least 24 h before the experiment. It informs subjects of the overall structure of the study and that earnings depend on the number of tasks completed. The specific tasks are not described.

For future research it is interesting to investigate different time spans between goal setting and the task to examine whether the time span matters and, if so, what time span is optimal. The optimal time span could depend, for example, on task characteristics (how difficult or boring it is), personal characteristics, or the interaction of these two.

There is a small difference between the mandatory work phase and the free work phase. In the latter, subjects have to reload the page for each table. Thus, subjects are slowed down slightly in the free work phase. The slider tool does not account for this or for potential improvements in productivity due to practice. But since it only takes a few milliseconds to reload the page, it is unlikely that this difference drives goal non-achievement. As the free work phase takes place after goals have been set/revised, this issue cannot drive goal revision.

One can extend our theoretical framework to allow for anticipation of goal revision (see Online Supplement S.1.2)—yielding predictions that are qualitatively similar to our hypotheses.

Such an anchor would work against our hypothesis that the revised goal 1 is lower than goal 0.

In Online Supplement S.8, we provide evidence that subjects indeed do not perfectly remember their goal.

The ethics rules of COBElab at Aarhus University did not allow us to enforce participation in all parts of the study by making all payments conditional on the completion of the post survey. We incentivized participation in the post survey by paying far more than the average student wage. Given the fixed budget, a further increase in incentives would have implied lower payments for earlier parts and possibly attrition problems there.

The explicit goal revision in Revise0 and Revise1 may induce subjects to revise their goal differently (more often or to a greater extent) than subjects in Early do. The prediction below remains valid if this is the case.

For robustness, we also use the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test (MWU) to examine differences in effort between treatments. Note, however, that a lack of control for productivity makes the MWU and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests ill-suited for comparing goals in Hypothesis 1, because these do not take into account the increase in productivity between dates 0 and 1 that mechanically increases goals.

The effect sizes for Hypothesis 1 in Table 2 are conservative estimates because Hedge’s \(g_p\) does not take into account that subjects become more productive from date 0 to date 1.

In Specifications (4) and (5) in Table 4, the intercept shows the average (fitted) goal revision in the case of no change in productivity. In Specification (6), however, it has a different interpretation since the regression is estimated with the full set of controls. This intercept is not informative about the overall difference between the goals, but instead captures the difference for a distinct baseline (including variables in a within-subject comparison that do not change between date 0 and date 1). Hence, it sheds light on possible mechanisms, which we return to in Sect. 6.

When controlling for the goal displayed to subjects, there is a significant difference between Revise0 and Revise1 in Specifications (4)-(6) of Table 6. But it is not robust to excluding outliers or running a median regression (results available upon request).

Conceptually, one would regress effort on both goal 0 and goal 1. However, such a test is hindered by collinearity of goal 0 and goal 1 (\(r =.75\), \(p<.001\)). Instead, we compare coefficients across specifications.

As in Koch and Nafziger (2020), comparison utility is defined over effort and we abstract from gains from overachieving the goal for reasons of parsimony. See Koch and Nafziger (2016) for a model where the individual experiences comparison utility over both gains and losses in the benefit and cost domains.

Also, note that \(g_1^*=e^*\) can occur in Revise1 if \(\lambda ^{Revise1}=0\), and \(g_0^*=e^*\) can occur in Early if \(\lambda ^{Early}=1\).

References

Abeler, J., Falk, A., Götte, L., & Huffman, D. (2011). Reference points and effort provision. American Economic Review, 101, 470–492.

Acland, D., & Levy, M. R. (2015). Naiveté, projection bias, and habit formation in gym attendance. Management Science, 61, 146–160.

Akina, Z., & Karagozoglub, E. (2017). The role of goals and feedback in incentivizing performance. Managerial and Decision Economics, 38, 193–211.

Anshel, M. H., Weinberg, R., & Jackson, A. (1992). The effect of goal difficulty and task complexity on intrinsic motivation and motor performance. Journal of Sport Behavior, 15, 159.

Augenblick, N., Niederle, M., & Sprenger, C. (2015). Working over time: Dynamic inconsistency in real effort tasks. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 1067–1115.

Augenblick, N., & Rabin, M. (2019). An experiment on time preference and misprediction in unpleasant tasks. Review of Economic Studies, 86, 941–975.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57, 289–300.

Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., & Shleifer, A. (2020). Memory, attention, and choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135, 1399–1442.

Brookins, P., Goerg, S. J., & Kube, S. (2017). Self-chosen goals, incentives, and effort, mimeo. Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods.

Campion, M. A., & Lord, R. G. (1982). A control systems conceptualization of the goal-setting and changing process. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 30, 265–287.

Card, D., & Dahl, G. B. (2011). Family violence and football: The effect of unexpected emotional cues on violent behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126, 103–143.

Cettolin, E., Cole, K., & Dalton, P. (2020). Developing goals for development: Experimental evidence from cassava processors in Ghana. Working paper, Tilburg University.

Chapman, S. L., & Jeffrey, D. B. (1978). Situational management, standard setting, and self-reward in a behavior modification weight loss program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 1588.

Chidester, T. R., & Grigsby, W. C. (1984). A meta-analysis of the goal setting-performance literature. In Academy of management proceedings. Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY, (vol. 1, pp. 202–206).

Clark, D., Gill, D., Prowse, V. L., & Rush, M. (2020). Using goals to motivate college students: Theory and evidence from field experiments. Review of Economics and Statistics, 102, 648–663.

Corgnet, B., Gómez-Miñambres, J., & Hernán-Gonzalez, R. (2015). Goal setting and monetary incentives: When large stakes are not enough. Management Science, 61, 2926–2944.

Corgnet, B., Gomez-Minambres, J., & Hernan-Gonzalez, R. (2018). Goal setting in the principal-agent model: Weak incentives for strong performance. Games and Economic Behavior, 109, 311–326.

Dalton, P. S., Gonzalez, V., & Noussair, C. N. (2015). Paying with self-chosen goals: Incentives and gender differences, CentER Discussion Paper Series No. 2016-036.

DellaVigna, S., Lindner, A., Reizer, B., & Schmieder, J. F. (2017). Reference-dependent job search: Evidence from Hungary. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132, 1969–2018.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9, 522–550.

Donovan, J. J., & Williams, K. J. (2003). Missing the mark: Effects of time and causal attributions on goal revision in response to goal-performance discrepancies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 379.

Epton, T., Currie, S., & Armitage, C. J. (2017). Unique effects of setting goals on behavior change: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 1182.

Erbaugh, S. J., & Barnett, M. L. (1986). Effects of modeling and goal-setting on the jumping performance of primary-grade children. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 63, 1287–1293.

Fan, J., Gómez-Miñambres, J., & Smithers, S. (2019). Make it too difficult, and I’ll give up; Let me Succeed, and I’ll excel: The interaction between assigned and personal goals. Managerial and Decision Economics, 41, 964–975.

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 25–42.

Gill, D., & Prowse, V. (2012). A structural analysis of disappointment aversion in a real effort competition. American Economic Review, 102, 469–503.

Goerg, S. J., & Kube, S. (2012). Goals (th)at work: Goals, monetary incentives, and workers’s performance, mimeo, Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods.

Gonzalez, V., Dalton, P. S., & Noussair, C. (2020). The dark side of monetary bonuses: Theory and experimental evidence, CentER Discussion paper.

Goudas, M., Ardamerinos, N., Vasilliou, S., & Zanou, S. (1999). Effect of goal-setting on reaction time. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 89, 849–852.

Grant, A. M. (2008). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 108–124.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250–279.

Harding, M., & Hsiaw, A. (2014). Goal setting and energy conservation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 107, 209–227.

Hayes, S. C., Rosenfarb, I., Wulfert, E., Munt, E. D., Korn, Z., & Zettle, R. D. (1985). Self-reinforcement effects: An artifact of social standard setting? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18, 201–214.

Heath, C., Larrick, R. P., & Wu, G. (1999). Goals as reference points. Cognitive Psychology, 38, 79–109.

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Activation: Accessibility, and salience. Social psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles (pp. 133–168).

Himmler, O., Jäckle, R., & Weinschenk, P. (2019). Soft commitments, reminders, and academic performance. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11, 114–42.

Hinsz, V. B. (1995). Goal setting by groups performing an additive task: A comparison with individual goal setting 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 965–990.

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6, 65–70.

Hsiaw, A. (2013). Goal-setting and self-control. Journal of Economic Theory, 148, 601–626.

Ilies, R., & Judge, T. A. (2005). Goal regulation across time: The effects of feedback and affect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 453.

Jain, S. (2009). Self-control and optimal goals: A theoretical analysis. Marketing Science, 28, 1027–1045.

Kaiser, J. P., Koch, A., & Nafziger, J. (2024). Replication data for: Does goal revision undermine self-regulation through goals? An experiment. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/49LVAT

Kaiser, J. P., Koch, A. K., & Nafziger, J. (2023). Results of the pre-analysis plan: Are self-set goals effective motivators? An experiment. Working paper. Aarhus University.

Karlan, D., McConnell, M., Mullainathan, S., & Zinman, J. (2016). Getting to the top of mind: How reminders increase saving. Management Science, 62, 3393–3411.

Kaur, S., Kremer, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2015). Self-control at work. Journal of Political Economy, 123, 1227–1277.

Kőszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2009). Reference-dependent consumption plans. American Economic Review, 99, 909–936.

Koch, A. K., & Nafziger, J. (2011). Self-regulation through goal setting. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113, 212–227.

Koch, A. K., & Nafziger, J. (2016). Goals and bracketing under mental accounting. Journal of Economic Theory, 162, 305–351.

Koch, A. K., & Nafziger, J. (2020). Motivational goal bracketing: An experiment. Journal of Economic Theory, 185, 104949.

Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 443–477.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice Hall.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57, 705–717.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5, 93–105.

Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2003). Projection bias in predicting future utility. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1209–1248.

McCalley, L., & Midden, C. J. (2002). Energy conservation through product-integrated feedback: The roles of goal-setting and social orientation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23, 589–603.

Mento, A. J., Steel, R. P., & Karren, R. J. (1987). A meta-analytic study of the effects of goal setting on task performance: 1966–1984. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39, 52–83.

O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (1999). Doing it now or later. American Economic Review, 89, 103–124.

Saccardo, S., Pietrasz, A., & Gneezy, U. (2017). On the size of the gender difference in competitiveness. Management Science, 64, 1541–1554.

Sackett, A. M., Wu, G., White, R. J., & Markle, A. (2014). Harnessing optimism: How eliciting goals improves performance. SSRN 2544020.

Schunk, D. H. (1985). Participation in goal setting: Effects on self-efficacy and skills of learning-disabled children. Journal of Special Education, 19, 307–317.

Šidák, Z. (1967). Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 62, 626–633.

Smith, A. (2019). Lagged beliefs and reference-dependent utility. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 167, 331–340.

Smith, M., & Lee, C. (1992). Goal setting and performance in a novel coordination task: Mediating mechanisms. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 14, 169–176.

Smithers, S. (2015). Goals, motivation and gender. Economics Letters, 131, 75–77.

Suvorov, A., & van de Ven, J. (2008). Goal setting as a self-regulation mechanism, working papers w0122, Center for Economic and Financial Research (CEFIR).

Tanes, Z., & Cho, H. (2013). Goal setting outcomes: Examining the role of goal interaction in influencing the experience and learning outcomes of video game play for earthquake preparedness. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 858–869.

Thakral, N., & Tô, L. T. (2021). Daily labor supply and adaptive reference points. American Economic Review, 111, 2417–2443.

Toussaert, S. (2016). Connecting commitment to self-control problems: Evidence from a weight loss challenge, mimeo, NYU.

Tubbs, M. E. (1986). Goal setting: A meta-analytic examination of the empirical evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 474.

van Lent, M. (2019). Goal setting, information, and goal revision: A field experiment. German Economic Review, 20, e949–e972.

van Lent, M., & Souverijn, M. (2020). Goal setting and raising the bar: A field experiment. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 87, 101570.

West, R. L., Welch, D. C., & Thorn, R. M. (2001). Effects of goal-setting and feedback on memory performance and beliefs among older and younger adults. Psychology and Aging, 16, 240.

Wood, R. E., Mento, A. J., & Locke, E. A. (1987). Task complexity as a moderator of goal effects: A meta analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 416–425.

Wu, G., Heath, C., & Larrick, R. (2008). A prospect theory model of goal behavior, mimeo. University of Chicago.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Interacting Minds Seeds at Aarhus University, Grant 2019-120, is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Aarhus Universitet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The study is pre-registered on OSF (https://osf.io/3q82y) and was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Cognition and Behavior lab, Aarhus University (21.10.2019, ID 272). In Kaiser et al. (2023), we report additional pre-registered analyses and document any changes from the pre-analysis plan. In particular, in Sect. 6, we mix reporting pre-registered mechanisms, pre-registered exploratory research and post hoc exploratory research; and we classify these analyses in the report. We thank the editors Roberto Weber and Arno Riedl, two anonymous referees, Elena Cettolin, Patricio Dalton, Daniele Nosenzo, Victor Gonzales Jiminez, Marco Schwarz, Ben Vollaard, seminar participants at the universities of Tilburg, Innsbruck, Wien, and Aarhus, the Annual Meeting of the Verein für Socialpolitik, the COPE and the CNEE Workshop for their helpful comments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1: Theoretical framework and analysis

Appendix 1: Theoretical framework and analysis

In the following, we develop a stylized theoretical framework to underpin the hypotheses for our experiment. We provide the formal analysis of the model in Appendix “Analysis”.

1.1 Model

1.1.1 Task and preferences

We derive our predictions in a theoretical model where people have present-biased preferences (Laibson, 1997). We allow for partial naïveté (O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999). That is, the individual is aware of facing a self-control problem but not necessarily of its full extent. In the absence of goal setting, the utility of self t (the incarnation of the individual at date \(t \in \{0,1,2\}\)) is \(U_t=u_t+\beta \,\left[ \sum _{\tau =t+1}^{T+1} \delta ^{\tau }u_{\tau }\right] ,\) where \(u_t\) is the instantaneous utility. The individual faces a task that requires effort \(e\in [0,\infty )\), causing immediate costs c(e) (strictly increasing and strictly convex) and long-run benefits b(e) (strictly increasing and concave). Thus, \(u_0=0\), \(u_1=-c(e)\) and \(u_{2}=b(e)\). The present bias parameter \(\beta \in (0,1]\) captures the extent to which the individual overemphasizes the immediate instantaneous utility relative to future instantaneous utilities. The individual might be fully or partially naïve about his present bias; that is, he holds a belief \(1\ge \hat{\beta }\ge \beta\) about his present bias. Without loss of generality, we set the exponential discount factor \(\delta\) to one.

The present bias causes time inconsistency. For self 0, all costs and benefits are in the future. Hence, the optimal effort equates marginal costs and benefits:

Self 1 discounts future benefits by \(\beta \le 1\) but not the immediate costs. So, self 1 prefers effort such that

Thus, a self-control problem arises because self 0 wants a higher effort than self 1: \(e_{0}^*\ge e_1^*\).

1.1.2 Goals

To overcome this self-control problem, self 0 sets an effort goal \(g_0\) at date 0. Consistent with the evidence from psychology on goals (e.g. Heath et al., 1999; Locke & Latham, 2002; Wu et al., 2008) and building on the models of Koch and Nafziger (2016, 2020), we assume that a goal serves as a reference point in that the individual compares the actual effort e with the goal g. If the effort differs from the goal by \(z=e-g\), the individual experiences a corresponding comparison utility \(\mu (z)=z\) for \(z<0\), and \(\mu (z)=0\) for \(z\ge 0\).Footnote 22

Self 1 may revise the goal \(g_0\) at date 1 to \(g_1\). We assume that an individual who (possibly) revises the goal at date 1 then compares the early goal set at date 0, \(g_0\), to the revised goal, \(g_1\), and experiences comparison utility from this change. If the revised goal differs from the early goal by z, the individual experiences a corresponding comparison utility \(\nu (z)=\nu \,z\) for \(z<0\) and \(\nu (z)=0\) for \(z\ge 0\). We assume \(0 \le \nu <1\), implying that adjusting one’s goal downward is psychologically less painful than failing to reach one’s goal. The idea that changes in beliefs about future outcomes are carriers of comparison utility and the weighting of this comparison utility follows Kőszegi and Rabin (2009).

We assume that both the early and the revised goals are ‘sticky’ in the sense that a combination of both goals enters the reference point to which the individual ultimately compares exerted effort. Specifically, the individual has \(g^*\) in mind with \(g^*=\lambda ^T\,g_0+(1-\lambda ^T)\,g_1\), where \(\lambda ^T\) and \(1-\lambda ^T\) are the treatment-specific salience weights (\(T\in \{Late,Early,Revise0,Revise1\}\))—see more on these weights below.

At the goal revision stage, the individual believes that he will evaluate performance against the reference point \(\hat{g}^*=\hat{\lambda }\,g_0+(1-\hat{\lambda })\,g_1\). To highlight the main driving forces and because it is a plausible scenario, we assume for expositional purposes that at the goal revision stage the individual is myopic about the stickiness of the original goal \(g_0\). Consequently, he does not take stickiness into account when setting the revised goal \(g_1\) and thinks believes that he will compare effort only to \(g_1\). This amounts to assuming \(\hat{\lambda }=0\). As shown in Online Supplement S.1.1,

the qualitative predictions of the model are robust to assuming correct anticipation of the stickiness of the original goal. Similarly, motivated by evidence on projection bias (cf. Loewenstein et al., 2003; Acland & Levy, 2015), we assume that self 0 is naïve about the possibility of revising goals. We discuss the implications of relaxing this assumption in Online Supplement S.1.2.

1.1.3 Equilibrium